论朱锫建筑的心灵景观

2017-07-12TheMindLandscapesofStudioZhuPei

The Mind Landscapes of Studio Zhu-Pei

莫森·莫斯塔法维/Mohsen Mostafavi

杜芳芳 译/Translated by DU Fangfang

论朱锫建筑的心灵景观

The Mind Landscapes of Studio Zhu-Pei

莫森·莫斯塔法维/Mohsen Mostafavi

杜芳芳 译/Translated by DU Fangfang

中国当代建筑正处在一个关键而又意味深长的转折点上。战后现代化发展初期,在像北京这样的中心城市里新兴的大型建筑项目普遍具有一种苏联模式的精神特质——不少大型建筑物都以建筑元素的简单的重复使用来象征权力和威仪。

在此后的现代化阶段,稍晚近的建筑风格开始趋向于接受更为当代的“西方”建筑实践。自1970-1980年代中国开始对外开放,以美国建筑师约翰·波特曼为代表、以及一批美国大型企业积极呼应这个国家全新的经济现实,在城市景观的转型上发挥了不容忽视的关键作用。结果就是,高层建筑群被视为“象征”,结集一处,划一地成为新的城市天际线。

一味向前发展和对利润的追逐常常以牺牲传统城市肌理为代价。在整个中国范围内,为了现代化发展,历史街区被纷纷夷平。这一方式迄今依旧主导着那些野心勃勃谋求“进化式”经济发展的大部分地区。然而,随着对传统建筑以及具有地方特色的建筑物的珍惜度的提高,上述趋势已经有所扭转。很多老建筑得到维护修复,有的得以复建。纵然品质高低千差万别,却足已验证整个社会态度的转变。当然,这一过程也与那些颇具建筑史意义的建筑物近年来大幅增长的货币价值不无关联。

普利兹克建筑奖获得者王澍的作品就是对这一变化保持敏感的例证之一。他和他的搭档陆文宇一起以通过对那些极具地方特色的材料与建造方式进行当代性阐释为基础,发展出他们特有的一套极为细腻的建筑语言。然而,很多其他当代建筑师在与建筑的地方性之间建立关系时则复杂而含蓄。他们试图在传统和现代之间摸索出一条自己的道路。可以预见,并且已经有大量佐证,今天新一代中国建筑师的设计正在以各自不同的方法修正这一关系。

朱锫的作品大多是当代艺术和文化场馆。在柏林Aedes当代建筑中心展出的朱锫建筑事务所的作品已然呈现出为中国当代建筑演变带入的重要贡献。朱锫的早期作品执着于更具当代性的材料和美学理念。他与西方前卫建筑师的建筑实践之间有着远比本土文化遗产和传统更多的相通之处。而展出的这组建筑项目表明了他已然与早期作品分野。从场所、材料到历史,他的关注点更加多元而广泛。这些因素在每个项目的建筑语言成型过程中都起了重要的辅助作用。尽管所有这些展出项目都致力于文化和艺术方面的探索,但因为每个项目都由特定方法入手,最终它们风格迥异。

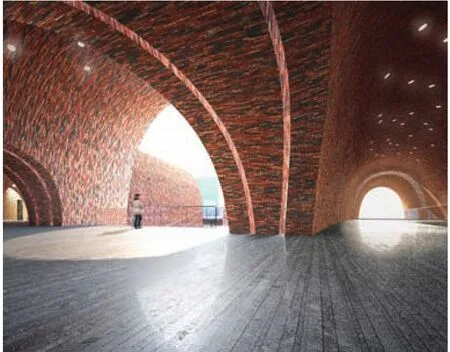

景德镇御窑博物馆——目前已经在中国瓷都开工建造——其设计灵感源自当地砖窑的构造传统。该博物馆平行的、线性的拱券结构,像古老的砖窑一样一直延伸至街面以下。这一设计策略部分源于城市对于历史街区内建筑物的高度限制,倒反而让建筑物在水平走向上卓有成效地形成了一种模糊性。建筑物一旦嵌入地面,自然就在街面上形成了一系列公共空间。尤为重要的是,这让在博物馆内设计几处更具私密性的庭院和平台成为可能。其中一个开放空间将直接展示地基纵深处历史肌理留下的痕迹。

从街道的视角上看,建筑物的拱形结构似乎只是一个个独立的单一元素,而实际上,它们在地面之上与地面以下都内在地相互连接。这让建筑的外观剥离于它的功能和内容、用途与实际状态。拱形结构或被分为上下两层,或被设计成带有一系列悬空水平面的单一空间,观众得以在建筑物里获得多样的空间体验。

博物馆的内部结构、建造方式和材料、色彩与灯光的选择纷繁复杂,与以减法获得的单纯外观相互映衬。该设计在视觉上让人联想起砖窑早期建造技术,而它的实际施工则完全是当代的建造方法。

展览中的其他项目——如杨丽萍表演艺术中心和大理当代美术馆,它们同在大理,并且同样设定在纯自然的环境中,对建筑与场所的关系的探索得以继续延展。表演艺术中心采取了建筑/华盖或洞穴/鸟巢的策略,不仅精确地勾勒出建筑元素之间强烈的内外关系,还将建筑基地加以最充分的利用。鸟巢华盖架在封闭的表演区外,它不仅为艺术中心另外辟出一块有屋檐遮护的具有实用性的区域,同时也融入周边地形的风景线。

大理美术馆同样也与自然背景直接融合。不过在这个案例中,由于紧邻宝塔古迹,美术馆的设计与背景山脉的斜坡地形完全融为一体。由此建造的一连串“绿色平台”,随自然地形绵延起伏。虽然美术馆主体嵌在地下,但从平台上伸出的一系列体块成为天际线上的亮点。同景德镇的项目相似,纵观这整个建筑群,似乎是分为不同的部分逐一发展出来的。这种建筑构思方法意味着使用者将不再单纯从正前方感受建筑,建筑不再仅仅是一个立面,而是空间内外之间的一系列流动的空间体验。这让建筑空间的感受犹如在风景间流线穿行。

因此,朱锫对中国山水画的浓厚兴趣虽在意料之外却在情理之中。这里所指的兴趣不仅是观察景观与建筑之间的关系,还包括不同时代的艺术家在不同的风格类型或表现手法上的山水画成就。尤为值得一提的是在元代达到巅峰的“意境”概念——画面呈现不应囿于画家对山林的忠实描绘,还应当体现或刻画画家的“意”——内在风景。

从这个角度看,该展览所展出的朱锫作品也是一系列“意境”。它们不只呈现了建筑和风景之间的关系,通过不同的设计,建筑师将自己的“意”全然融入创作实现中。

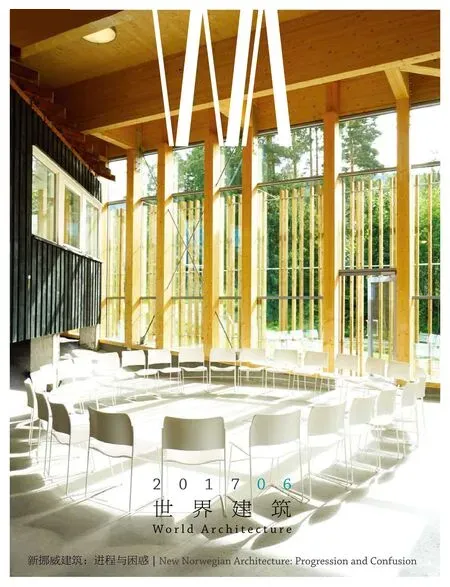

1 自御窑厂国家考古遗地公园远观御窑博物馆

2 御窑博物馆室内局部空间

Contemporary Chinese architecture is at an interesting and important point of transition. The major architectural projects of the postwar period of modernization and development in cities like Beijing can be characterized as proto-Soviet in spirit, with many large-scale buildings using simple and repetitive elements of construction to symbolize power and authority.

The more recent period of modernization, however, has embraced a more contemporary "Western" approach to architecture. With the opening up of China's in the 1970s and 1980s, architects such as John Portman and other large US corporate firms played a significant role in the transformation of the urban landscape by responding to the country's new economic realities.The outcome, invariably, was city skylines made up of amalgams of "iconic" high-rise structures.

The search for progress and profit often came at the expense of the traditional fabric of the city. Across China historic districts were razed in order to create modern developments. This is an approach that still prevails in many areas of the country in pursuit of financially ambitious and "progressive" developments.

But there has also been a reversal of this trend, with a growing appreciation of traditional and vernacular architecture. The conservation and at times reconstruction of many older buildings, albeit with varying degrees of success, attests to a change in societal attitudes. Of course this process is not disconnected from the enormous increase in the monetary value of many architecturally significant buildings.

The work of Pritzker-winning architect WANG Shu is one manifestation of this change in sensibility. He and his partner LU Wenyu have developed a subtle body of architecture that builds on contemporary interpretations of vernacular materials and construction. But many other contemporary architects have formed a complex and perhaps less overt relationship to vernacular architecture as they have attempted to negotiate their own path between tradition and modernity. As can be expected, there are various recalibrations of this relationship in evidence in the projects of a new generation of Chinese architects today.

The work of Studio Zhu-Pei, as seen through the selection of projects on show at the Aedes Gallery, represents an important contribution to the evolution of contemporary architecture in China. ZHU Pei's earlier work can be characterized by its dedication to a contemporary material and aesthetic ethos that had more in common with the practices of Western avant-garde architects than it did with local heritage and traditions. The majority of ZHU Pei's body of work is composed of contemporary art and cultural institutions.

The cluster of projects shown in the current exhibition indicates a departure from the earlier work, pointing to a more varied range of interests based on location, materials, and history. These factors play an important part in helping shape the architecture of each project. And even though all the projects on display are still concerned with cultural and artistic endeavors, they are quite diverse in appearance as each is defined by a specific approach.

The Jingdezhen Historical Museum of Imperial Kiln, currently under construction in China's capital of porcelain, is a building that draws its inspiration from the local traditions of kiln construction. The parallel, linear, and arched structures of the museum, like the old kilns, reach below the level of the street. This strategy - in part also a response to height restrictions in the historic district of the city - leads to a productive ambiguity in relation to the building's horizontal datum. The "insertion" of the building into the ground of the site produces a series of public spaces at street level; also, more importantly, it allows for the design of a number of more intimate courtyards and terraces within the museum. One of these open spaces will also reveal the traces of the historic fabric on the site.

From the street, the building's arched structures appear as independent singular elements, but they are in fact connected internally above and belowground. This enables the building to present an external view that differs from its functional and programmatic use and reality. In section, the arched structures are either divided into two floors or designed as a single space with a series of suspended levels - an approach that will provide the visitor with a variety of spatial experiences of the building.

The reductive simplicity of the museum's external appearance is complemented by the complexity evident in its internal organization, method of construction, and choice of materials, colors, and lighting. While the design visually recalls the earlier technique of kiln construction, its execution is rooted in contemporary methods of construction.

Other projects in the exhibition, such as the Yang Liping Performing Arts Centre or the Museum of Contemporary Art, both in Dali, extend the exploration of architecture in relation to site; both these examples are located within natural settings.

The Performing Arts Center adopts a building/ canopy or cave/nest strategy to create a project that makes the most of its location by articulating a strong inside/outside relationship between the building elements. The nest canopy hovers over the external area of the enclosed performance spaces and defines a covered domain for use by the performing center while establishing a new horizon with the surrounding topography.

The Museum of Contemporary Art likewise engages directly with the natural setting. However, in this instance, because of the close proximity of a historic site with a pagoda, the museum is literally immersed within the sloping topography of the mountain setting, giving rise to a series of undulating "green terraces" that follow the natural shape of the site. While the main area of the museum is accommodated below ground, there is a series of structures protruding from the terraces that also act as skylights. As with the Jingdezhen project, the overall sense of the complex is of a building that is very much developed in section. This mode of conceiving architecture means that the user experiences the building not in purely frontal terms, as a façade, but as a series of fluid experiences between inside and outside. The feel of these buildings is more akin to meandering through a landscape.

It is therefore not surprising to discover that ZHU Pei is deeply interested in the history of Chinese landscape painting. And what seems of interest in this context is not just the connections between landscape and architecture, but also the way in which different generations of artists have construed the various genres or artifices of landscape painting. In particular, with the concept of "mind landscapes" developed during the Yuan dynasty, the idea was that the representation should not be limited to the depiction of the artist's garden, but should also embody or describe the artist's mind.

It is in this sense that the work by Studio Zhu-Pei presented in the exhibition is also a series of "mind landscapes", describing not only the relationship between architecture and landscape but also, through their designs, the minds of the architects involved in their realization.