果品主要真菌毒素污染检测、风险评估与控制研究进展

2017-02-24李志霞聂继云闫震张晓男关棣锴沈友明程杨

李志霞,聂继云,闫震,张晓男,关棣锴,沈友明,程杨

(中国农业科学院果树研究所/农业部果品质量安全风险评估实验室(兴城),辽宁兴城 125100)

果品主要真菌毒素污染检测、风险评估与控制研究进展

李志霞,聂继云,闫震,张晓男,关棣锴,沈友明,程杨

(中国农业科学院果树研究所/农业部果品质量安全风险评估实验室(兴城),辽宁兴城 125100)

果品在生产、贮运过程中易发生真菌性病害,不但可引起腐烂或腐败,带来严重的经济损失,部分霉菌还可能产生真菌毒素对人体健康造成潜在危害。真菌毒素是一类由丝状真菌在适宜条件下产生的有毒次级代谢产物,是继农药残留、重金属污染后,影响果品质量安全的又一类关键风险因子,具有强毒性。大量研究表明,真菌毒素可致DNA损伤,低浓度下即可对人和动物健康造成危害,使肝脏、肾脏和胃肠道发生病变,并且可致癌、致畸、致突变等,研究真菌毒素的污染状况,进行精准检测、风险评估和控制,对于果品质量安全研究具有重要意义。展青霉素(Patulin,PAT)、黄曲霉毒素(Aflatoxins,AF)、链格孢毒素(Alternaria toxins)和赭曲霉毒素A(Ochratoxin A,OTA)是存在于果品中的主要真菌毒素种类,国际癌症研究机构(IARC)分别将PAT、AFB1、AFM1和OTA列为第3类、1类、2B类和2B类致癌物质。通常果品中检出的真菌毒素含量极低,因此对检测方法的要求较高,目前主要的分析方法有薄层色谱法、高效液相色谱(含质谱联用)技术、气相色谱(含质谱联用)技术、毛细管电泳技术等,但往往由于化学结构和性质各异,无法采用一种标准方法完成对所有真菌毒素的定量测定。因此,筛选准确、高效、快速的检测方法也是该领域当今的研究热点。迄今为止,已有80个国家和地区制定了果品中真菌毒素的限量标准来保护消费者健康,但均未涉及链格孢霉毒素。许多国家均不同程度地开展了真菌毒素风险评估研究,基于毒理学数据的评估结果表明,大多情形下通过果品摄入的真菌毒素水平极低,不会对居民健康产生危害。果品中的真菌毒素可采用化学、物理、生物等方法进行防治、降解和控制,但无法将被真菌毒素污染后产品中的毒素完全脱除,果品中真菌毒素污染重在“防”而非“除”。 本文从果品中主要真菌毒素的种类、污染状况、毒性、检测方法、限量标准、风险评估及控制技术等方面进行概述,同时,对果品中真菌毒素的重点研究方向进行了展望,以期为该领域研究者提供参考。

果品;真菌毒素;展青霉素;黄曲霉毒素;链格孢毒素;赭曲霉毒素A;风险评估

0 引言

中国是果品生产大国,2014年水果(含瓜类)和坚果产量分别达2.5×108t和3.6×106t,果品总产量居世界首位[1]。果品是国民日均膳食中除蔬菜和粮食外摄入量(推荐300 g)最多的农产品,其质量安全关乎国计民生和社会安定,成为政府高度重视、社会广泛关注的热点和焦点[2]。越来越多的研究表明,真菌毒素污染是继农药残留、重金属污染后,影响果品质量安全的又一类关键风险因子,不仅为害人体健康,也直接造成严重的经济损失和频繁的国际贸易纠纷,引起了国际社会的广泛关注[3-6]。

真菌毒素(Mycotoxin)是一类由丝状真菌在适宜条件下产生的有毒次级代谢产物,可自然发生于果品生产、采收、贮藏和运输过程的各个环节[6],其共同毒性主要是致DNA损伤和细胞毒性,低浓度下即可对人和动物健康造成危害,使肝脏、肾脏和胃肠道发生病变,甚至致癌、致畸、致突变等[7-9]。关于果品中的真菌毒素,不少发达国家均不同程度地开展了真菌毒素产生、鉴定、监测、防控等相关研究[10-15]。目前,中国对真菌毒素检测识别的研究大多集中在谷物、粮食、粮油等农产品上[16-18],果品中对苹果及制品展青霉素污染研究相对较多[19-20],近年来开始有对苹果汁中链格孢霉毒素和果酒中赭曲霉毒素 A的少量报道[21-22],中国果品真菌毒素研究远不能满足政府监管、产业发展和公众消费的需求。因此,有步骤、有重点地开展果品真菌毒素研究具有重要的现实和科学意义。

1 果品中主要真菌毒素的种类、污染及其毒性

影响果品质量安全且普遍存在于果品中的真菌毒素主要包括展青霉素、黄曲霉毒素、链格孢毒素和赭曲霉毒素A,其毒性特点各不相同。

1.1 展青霉素(Patulin,PAT)

PAT又称棒曲霉素、珊瑚青霉毒素,是由曲霉和青霉等真菌产生的一种次级代谢产物,主要由扩展青霉产生[23]。PAT首先在霉烂苹果和苹果汁中被发现,由于果皮受伤被病原菌侵染即可诱导其产生,同时极易感染周围的健康果肉组织[24],且在冷藏条件下、加工过程中和制品中均能够稳定存在[25-26],因此PAT被认为是全球果品中最重要的毒素种类,不但广泛存在于苹果及其制品中,在梨、草莓、蓝莓、樱桃等果品中也均有检出[5,12,27]。据报道,新鲜水果中很少有PAT产生,霉菌侵染的果品中腐烂部位PAT含量最高,可高达1 000 μg·kg-1以上;整果平均含量可达21—746 μg·kg-1;用腐烂原料果制成的水果制品中 PAT可达0.79—140 μg·kg-1[5,27]。

PAT在20世纪60年代被重新分类界定为真菌毒素。因对人体具有潜在致癌性,国际癌症研究机构(IARC)将其列为第3类[28]。毒理学试验表明,PAT具有影响生育、免疫、遗传、神经系统、致癌、致畸等毒理作用[29-30]。按物种和暴露量不同,PAT的半致死剂量LD50范围约为15—25 mg·kg-1[5],对人体的危害很大,急性症状包括肺和脑水肿,肝、脾和肾功能损害,以及胃肠功能紊乱、免疫系统受损等;慢性症状包括神经麻痹、致畸、胚胎毒性、致原生质膜破裂、使DNA、RNA和蛋白质合成受阻等[3,31]。

1.2 黄曲霉毒素(Aflatoxins,AF)

AF是一类化学结构相似的二氢呋喃香豆素的衍生化合物,主要由黄曲霉和寄生曲霉产生。1960年,英国有10万只火鸡死于“火鸡X病”,进一步研究发现这些火鸡的死因是吃了被黄曲霉污染的花生粕,由此AF被发现并得到广泛研究[32]。AF主要有B1、B2、G1和G24种,以AFB1毒性最大和研究最多。最易受AF污染的是粮食作物,近年来,坚果、新鲜水果及其干制品中也陆续有AF检出,特别是干果和坚果中较常见。JUAN等[33]研究表明,摩洛哥拉巴特-萨累地区的核桃、开心果、葡萄干、无花果干中AFB1平均含量为0.16—367.6 μg·kg-1。IQBAL等[34]对巴基斯坦2个省96个枣样品及57个枣制品进行了AF含量检测,39.6%的枣样品和31.6%的枣制品均有AF检出,含量在2.76—4.96 μg·kg-1,分别有13.7%和17.0%的样品污染水平超过了AFB1和AF总量的限量值。BAMBA等[35]发现柠檬被病原菌Aspergillus flavus侵染后,AF含量可达141.3—811.7 μg·kg-1。

AF毒性极强,1993年AFB1被IARC划定为1类致癌物,是目前已知最强致癌物之一;2002年AFM1被列为2B类致癌物[36-37]。按物种和暴露量不同,AFB1的LD50在0.3—18 mg·kg-1左右[5],对哺乳动物、鸟类、鱼类具有致癌、致畸、致突变和肝毒性,这和 AFB1可与细胞DNA结合的特性有关[38]。AFB1毒性极强,是氰化钾的10倍、砒霜的68倍,在亚洲和非洲进行的许多流行性病学研究表明,食物中AF含量与肝细胞癌症发生呈正相关[39]。

1.3 链格孢霉毒素(Alternaria toxins)

链格孢菌可在水果运输和储存过程中或低温潮湿环境下产生并繁殖,导致水果腐败。链格孢菌产生的真菌毒素代谢物按结构可分为3类:四氨基酸衍生物—细交链格孢菌酮酸(Tenuazonic acid,TeA);二苯并吡喃酮衍生物—交链孢酚(Alternariol,AOH)、交链孢酚单甲醚(Alternariol monomethyl ether,AME)和链格孢霉素(Altenuene,ALT);二萘嵌苯类衍生物—细格菌毒素Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ(AltertoxinⅠ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ,ATX-Ⅰ、ATX-Ⅱ、ATX-Ⅲ)等[40]。果品中最为常见的类型为AOH、AME和TeA,迄今为止,已在草莓、黑莓、红醋栗、蓝莓、苹果、柑桔、橄榄等果品[41-46]及制品中[47-48]检测到链格孢霉毒素,浆果类水果的检出率较高,AOH、AME、TeA检出率达25%—75%,含量最高可达2778 μg·kg-1,腐烂部位含量更高[41-42]。

链格孢霉毒素对细菌和哺乳动物具有致癌、致畸、致突变和细胞毒性,AOH和AME急性毒性较弱但可显示协同效应,TeA毒性最强[5]。PANIGRAHI等[49]试验显示,TeA、AOH、ATX I 和ALT的 LD50分别为75、100、200和375 μg·mL-1。LIU等[50]发现,河南林县食管癌人群高发与当地粮食被链格孢霉毒素污染有关。ZHOU和QIANG[51]研究表明,TeA在浓度12.5—400 g·mL-1时,可抑制白鼠成纤维细胞、仓鼠肺细胞、人体肝细胞的再生和总蛋白含量。有研究者认为,TeA可能与发生在非洲的人类血液紊乱疾病“奥尼赖病(onyalai)”有关[52]。

1.4 赭曲霉毒素A(Ochratoxin A,OTA)

OTA于1965年首次从赭曲霉中分离出来,是由曲霉属和青霉属产生的有毒代谢产物,由一个氯化的二氢异香豆素衍生物通过一个肽键与L-β-苯丙氨酸的7-羧基相连而形成,因此对温度和水解作用表现极为稳定[5]。研究[53-54]表明,焙烤只能使OTA毒性减少20%,蒸煮对OTA毒性不具有破坏作用,温度达到100—200℃都不能完全分解。OTA广泛分布于自然界,果品中以干果、葡萄及其制品污染率最高,研究最广。果酒和果醋、干果中OTA污染发生率可达50%—100%,含量分别为0.2—6.4 μg·L-1和0.1—6 900 μg·L-1[53,55-56]。另外,在被病原菌侵染的桃、樱桃、草莓、苹果和柑橘等水果中也发现有少量的OTA,且去除腐烂部位后仍可进一步侵染,含量为0.15—29.2 μg·kg-1[57-58]。

OTA具有强烈的肾毒性、肝毒性和免疫毒性,并有致癌、致畸和致突变作用,被IARC划定为2B类致癌物[56,59]。在已发现的真菌毒素中,OTA被认为仅次于黄曲霉毒素而列第二位。由于其毒性较高,JECFA建议其每日耐受摄入量为 0.2—14 ng·kg-1bw·d-1[60],EFSA建议其每日耐受摄入量为17 ng·kg-1bw·d-1[61]。前人研究[62]发现,巴尔干地方性肾炎(BEN)和尿路癌(UT)的发生可能与OTA摄入有密切关系,患病人群血液中 OTA含量明显高于未感染人群,肾脏是OTA毒性作用的主要靶器官。也有研究者[63]认为,这2种疾病的发生与马兜铃酸(Aristolochic acids)的摄入有相关性,而非OTA。

2 果品真菌毒素分析方法

通常,果品中真菌毒素含量极低,需筛选准确、灵敏的方法对其进行检测,且由于不同真菌毒素的化学结构和性质各异,无法采用一种标准方法完成对所有真菌毒素的定量测定[64]。目前,真菌毒素检测常用的样品前处理方法有液液萃取技术(liquid-liquid extraction)、固相萃取技术(solid phase extraction,SPE)、超临界流体萃取技术(supercritical fluid extraction,SFE)、凝胶色谱净化技术(gel permeation chromatography,GPC)和免疫亲和层析净化技术(immunoaffinity cleanup,IAC)等;主要检测分析方法有薄层色谱法、高效液相色谱法(含液质联用技术)、气相色谱法(含气质联用技术)、毛细管电泳技术等,其中以LC-MS-MS的应用前景最广阔。

2.1 薄层色谱法(thin-layer chromatography,TLC)

TLC是检测真菌毒素的一种传统方法,其优点是可同时做大量样品、成本较低,缺点是样品前处理相对繁琐复杂、所用溶剂和展开剂毒性较大、灵敏度较低,因此实际应用受到一定限制。但随着与SPE、IAC等前处理手段联用、前处理自动化研究等,TLC法在真菌毒素多残留检测方面仍有一定的应用前景。WELKE等[65]采用TLC法结合电荷耦合装置(CCD)对苹果汁样品中的PAT含量进行了测定,检出限低至0.005 μg·L-1。ELHARIRY等[66]采用TLC-PCR-RAPD方法对腐烂苹果不同部位及所得果汁中的 PAT污染情况进行了测定,并对分离的8个条带进行了基因测序。SANTOS等[67]采用IAC-TLC法对生咖啡中的OTA进行测定,方法回收率为98.4%—103.8%,检出限达到 0.5 μg·kg-1。

2.2 高效液相色谱法(high-performance liquid chromatography,HPLC)

HPLC法测定真菌毒素是20世纪70年代中期发展起来的,具有分离和检测效能高、分析快速等特点,是目前真菌毒素检测最重要的方法,应用极为广泛。某些自身产生荧光的真菌毒素如AFs、OTA等,可直接用配有荧光检测器(fluorescence detector,FLD)的HPLC进行分析,分子中不含发色基团的毒素(如伏马菌素)或本身可产生荧光但强度较弱的毒素(如AFBl和AFGl)进行HPLC分析时,需经柱前或柱后衍生、优化流动相条件(如使用离子对试剂、改变流动相 pH 等)以增强荧光信号方能定量检测[3]。MYRESIOTIS等[68]采用QuEChERS 结合HPLC-DAD方法对石榴及石榴汁中AOH、AME和TEN等3种链格孢霉毒素进行检测,结果显示方法线性关系在0.9937以上,RSDs在0.53%—2.52%,回收率在82.0%—109.4%,AOH和AME检出限为0.015 μg·g-1,TEN检出限为0.02 μg·g-1。HPLC与质谱技术联用可在提高分析灵敏度和可靠性的同时,又能检测并鉴定多种不同种属的真菌毒素,因此,LC-MS或LC-MS/MS技术已越来越多地用于真菌毒素多残留测定。SULYOK等[69]采用半定量LC-MS-MS方法,对160个水果和坚果样品中 23种真菌毒素进行了多残留检测;PERRE等[41]也建立了半定量LC-TOF-MS方法,对50个浆果样品中AOH、AME、OTA、FB1、FB2、FB3等6种真菌毒素进行了分析;ZWICKEL等[70]建立的HPLC-MS/ MS方法可对果蔬汁和酒中12种链格孢霉毒素进行同时检测,检出限和定量限分别为0.10—0.59 μg·L-1和0.4—3.1 μg·L-1。国内,研究者先后对水果及果汁中多种真菌毒素的HPLC(MS/MS)检测技术进行了有益探索和分析[15,21-22,71],这些研究为今后果品中真菌毒素的筛查与分析提供了参考和依据。

2.3 气相色谱法(gas chromatography,GC)

某些食品中真菌毒素的GC测定方法已标准化,一般用于食品中真菌毒素的定期鉴别与定量,通常与质谱技术联用,使用火焰离子检测器(flame ionization detector,FID)或傅里叶变换红外光谱技术(fourier transform infrared spectroscopy,FTIR)对目标物质进行分析[64]。大多数真菌毒素不具有挥发性,需衍生后再使用 GC法进行测定。KHARANDI等[72]利用QuEChERS前处理、N,O-双(三甲基硅烷基)三氟乙酰胺衍生和GC-MS方法对苹果汁中PAT进行测定,回收率为79.9%—87.9%,检出限和定量限分别为0.4 μg·L-1和 1.3 μg·L-1,RSDs低于 9.5%。JIMÉNEZ和MATEO[73]采用HPLC和GC方法同时对香蕉中由镰刀菌产生的单端孢霉烯族毒素等 11种真菌毒素进行检测,发现大多数真菌毒素采用HPLC法测定效果更好,仅2种毒素可用GC法测定。总体而言,鉴于HPLC法低成本、灵敏、高效等优势,其在真菌毒素检测中大范围推广应用的可能性更大。

2.4 毛细管电泳技术(capillary electrophoresis,CE)

CE是20世纪80年代发展起来的一种新型液相分离技术,具有分离模式多、分离效率高、分析速度快、试剂和样品用量少、易于调控、对环境污染小等优点,目前在很多领域均有应用,但对果品中真菌毒素的检测仅见苹果汁中 PAT和果酒中 OTA的报道。MURILLO-ARBIZU等[74-75]分别采用毛细管微乳电动色谱法和毛细管胶束电动色谱法测定了 20份市售苹果汁中的PAT含量,检出限分别为3.2 μg·L-1和0.7 μg·L-1,定量限分别为8.0 μg·L-1和2.5 μg·L-1,回收率分别为75.3%和80.2%。GONZÁLEZ-PEÑAS等[76]和LUQUE等[77]分别采用CE-DAD法和毛细管胶束电动色谱法测定了 27份加度葡萄酒以及从果品等食品分离出的真菌条带中的OTA含量,同时与HPLC方法进行比较验证,证明CE可有效检测真菌毒素,但与LC-MS-MS方法相比检出限较高,用于实际样品检测时灵敏性可能达不到要求。

3 果品真菌毒素限量标准

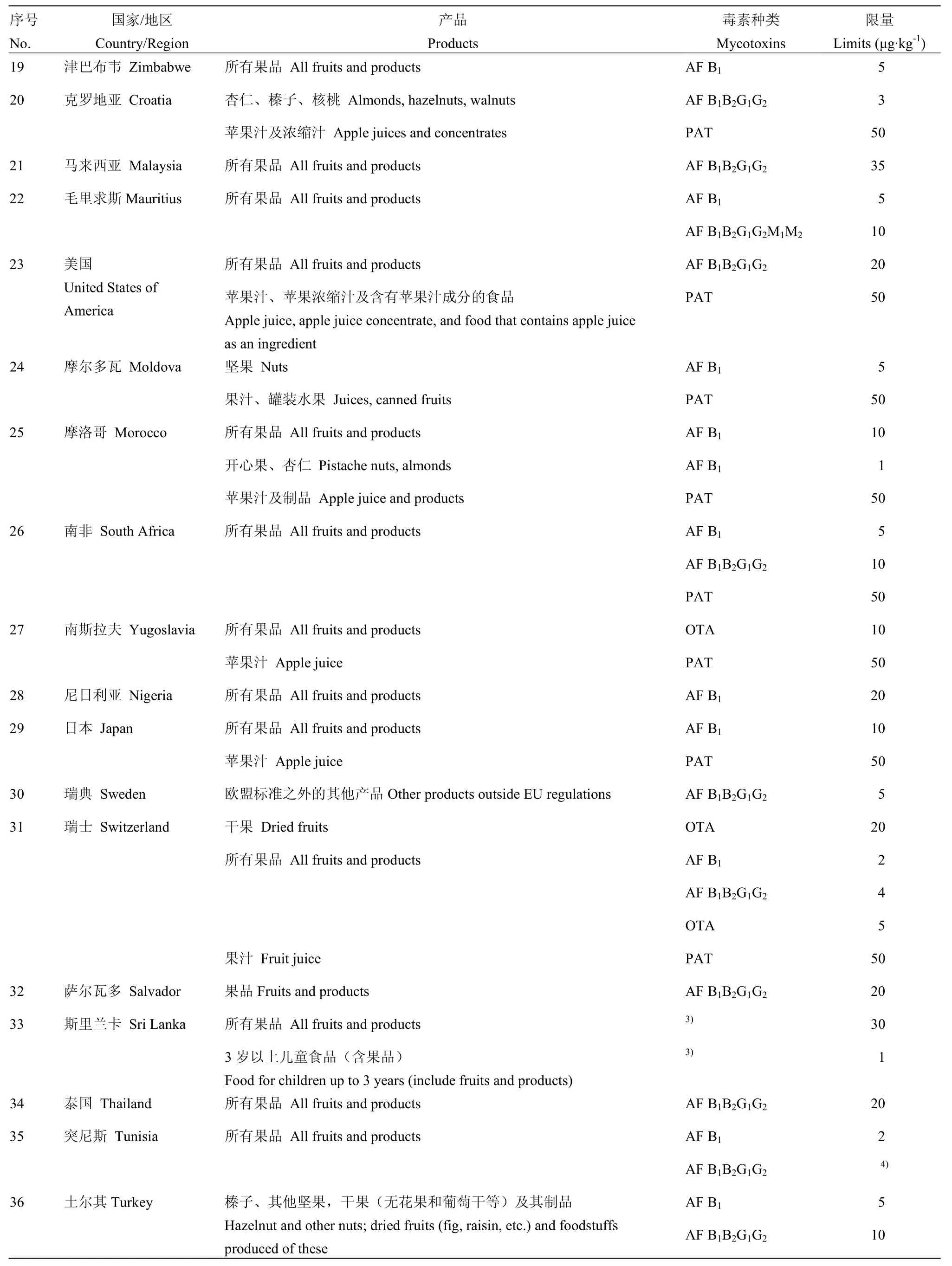

为保护消费者健康,许多国家和国际组织均制定了水果及相关产品中真菌毒素的限量标准。黄曲霉毒素是最受关注的真菌毒素种类,近年来其他真菌毒素限量标准的制定也得到了较快发展[6],但迄今尚无国家和地区制定果品中链格孢霉毒素限量。国际食品法典委员会(Codex Alimentarius Commission,CAC)分别于 1981年、1987年、1995年和 2003年举行了4次全球范围的真菌毒素限量标准调查,并随后发布了相关限量标准[78-81]。根据联合国粮食及农业组织(Food and Agriculture Organization,FAO)的最新调查[81],制定果品中真菌毒素限量标准的国家和地区共涉及80个,中国在2011年对食品中真菌毒素限量标准(GB 2761—2011)[82]进行了修订。国际组织和各国关于果品中真菌毒素的限量标准制定情况见表1。

目前已制定的果品真菌毒素限量标准,大多对所有果品、干果与坚果中的AF和OTA以及果汁、果酱、果酒或苹果制品中的PAT关注度较高。主要真菌毒素中,制定 AF(包括AFB1、AFB1+B2+G1+G2、AFM1等)限量标准的国家最多,涉及77个国家和地区,仅CAC、白俄罗斯和南斯拉夫未制定;其次为PAT,涉及55个国家和地区;再次为OTA和ZEA,分别涉及36个和3个国家和地区;DON仅乌克兰有制定;T-2仅亚美尼亚有制定。欧盟(European Union,EU)、乌克兰和伊朗制定的果品真菌毒素限量标准涉及的产品种类和毒素种类最为全面。相对而言,EU制定的果品真菌毒素限量标准较为严格,也有个别国家对指定产品的毒素限量比EU更严格,如摩洛哥规定开心果和杏仁中AFB1的限量为1 μg·kg-1;克罗地亚规定杏仁、榛子、核桃中AFB1+B2+G1+G2的限量为3 μg·kg-1。大多数国家制定的AFB1限量为5 μg·kg-1,AFB1+B2+ G1+G2为10或20 μg·kg-1,PAT为50 μg·kg-1;中国制定的标准包括熟制坚果及籽类中 AFB1限量为 5 μg·kg-1,除果丹皮外的水果及制品、果汁、果酒中PAT的限量为50 μg·kg-1(表1)。

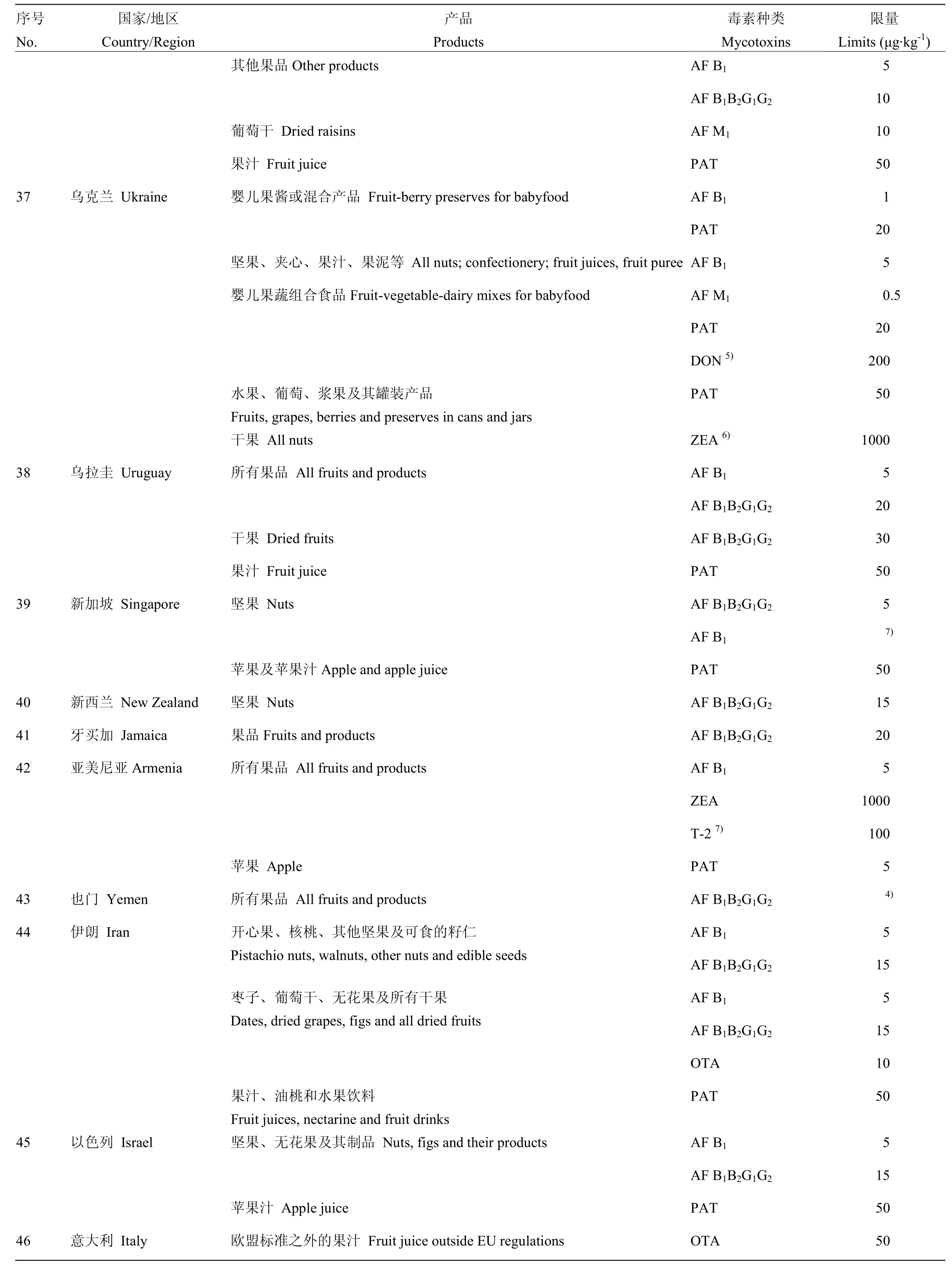

4 果品真菌毒素污染风险暴露评估

真菌毒素作为最主要的世界性农产品质量安全风险因子之一,其风险评估研究在全球范围内受到关注,也引起了科学家们的极大兴趣。尽管各类食品中真菌毒素的污染情况已有广泛研究,但目前国内外关于真菌毒素风险评估的报道主要集中在两个方面:一是全膳食暴露风险评估的研究[84-86],二是不同人群摄入粮食产品中某(几)种真菌毒素的膳食风险研究[87-88],关于果品中真菌毒素的膳食暴露风险评估研究尚在探索阶段。与其他危害因子风险评估程序一致,果品中真菌毒素风险评估包括危害识别、危害描述、暴露评估和风险描述4个步骤,暴露评估是研究的核心内容。现有研究多为结合食品消费量和真菌毒素污染水平计算估计膳食摄入量的点评估方法,以及基于@RISK分析软件的概率评估技术[60,89-90],得出的膳食摄入量数据再与基于毒理学数据推导或制定出的人类健康指导值(表2)进行比较,来评估人体膳食暴露风险。

近几年来,研究者针对不同人群,主要围绕苹果及制品中的PAT[30,84,89-90]、干果及葡萄制品中的OTA[56,85,91]、坚果和干果中的AF[84,91]等产品种类和真菌毒素种类进行了膳食暴露风险评估,结果显示,除极少量高污染样品、婴幼儿和儿童等高风险人群、P97.5或P99.9高百分位点值等情形下的膳食风险可能超出推荐限值外,其他大多数情形下果品中真菌毒素污染水平极低,不会对居民健康产生危害,一般婴幼儿和儿童的风险高于成人。健康指导值常用每日耐受摄入量(The tolerable daily intake,TDI)、临时每日耐受摄入量(provisional tolerable daily intake,PTDI)、临时最大每日耐受摄入量(provisional maximum tolerable daily intake,PMTDI)、临时每周耐受摄入量(provisional tolerable weekly intake,PTWI)等表示。目前报道的果品中真菌毒素膳食风险评估结果如表 3所示。鉴于目前真菌毒素毒理学资料、膳食数据和污染数据的缺乏,科学家认为真菌毒素膳食暴露风险评估研究应进一步深入开展,同时亟需根据评估结果对真菌毒素限量标准进行完善[6,60,83]。

表1 国际组织和各国制定的果品中真菌毒素限量标准[78,82-83]Table 1 Maximum tolerated levels for mycotoxins in fruits and the products worldwide

续表1 Continued table 1

续表1 Continued table 1

续表1 Continued table 1

表2 食品添加剂联合专家委员会建议的主要真菌毒素健康指导值[60]Table 2 The Health-based guidance value for main mycotoxins made by JECFA

5 果品真菌毒素污染控制技术

果品中碳水化合物、水分等较高,极易被真菌病害侵染,侵染后因霉变、腐烂和产生真菌毒素等可造成巨大的经济损失。如何有效地削减和控制果品中真菌毒素的污染,保障其质量安全是农业和食品加工领域亟待解决的重要课题。李培武等[2]认为,真菌毒素的控制应包括控制霉菌生长、控制菌株产毒和消减毒素3个层面,目前研究最多的是毒素消减或脱毒技术,控制毒素产生和消减技术通常采用化学、物理或生物

学的方法,无论何种方法,对果品中的真菌毒素应重在“防”而非“除”。

表3 果品中真菌毒素膳食暴露风险评估报道Table 3 Reported dietary intake assessment and risks of mycotoxins in fruits and the products

5.1 化学方法

化学方法即使用杀菌剂、防腐剂、添加剂、抗氧化剂等化学物质来抑制真菌和毒素生长或消减的方法。从安全角度来讲,虽然并不提倡使用这些化学物质,但考虑到实际生产中真菌病害侵染往往可造成较大的经济损失,同时相比之下真菌毒素的毒性较这些化学物质要高得多,因此,目前化学处理仍为果品中主要使用的真菌病害及其毒素控制方法[6]。MALMAURET等[97]研究表明,许多不使用化学杀菌剂的有机苹果中真菌毒素污染比法国传统生产的苹果中高。类似的结果分别在西班牙、意大利、比利时等国家也有报道[30,90,98-99]。其他化学物质如芳香物质、精油等也被用于霉菌和真菌毒素的防控中,NERI等[100]用反式-2-己烯醛处理接种青霉菌(P. expansum)的梨果实,发现霉菌生长受到显著抑制。GEMEDA等[101]用精油处理曲霉的试验发现,3种精油均可不同程度地抑制霉菌生长和AF的产生,效果优于合成的防腐剂。在发现更为有效的控制真菌毒素方法前,化学方法可能还将在今后较长时间内普遍应用。事实上,只要按照国家规定的浓度、用量和安全间隔期使用,杀菌剂、防腐剂、添加剂、抗氧化剂等物质对果品的安全及人体健康产生的危害是很有限的[102]。

5.2 物理方法

物理方法主要有剔除霉粒法、物理吸附法、淘洗法、辐照法、高温高压法等,传统而言,热处理为真菌毒素消减最常用的方法,包括热水浸洗、干热处理、蒸汽加热、热水喷淋处理或日光晾晒等,研究者分别在苹果、荔枝、芒果、西瓜、桃、梨、草莓等果品上进行了相关试验,表明这些热处理方法可将真菌毒素污染水平降低 20%—70%,但不能完全脱除[6]。近几十年来,辐照法因节约能源、无二次和交叉污染、无残留、工艺简单、快速高效等优点,被广泛用于食品和农产品真菌毒素降解领域,其中最为常用的是γ射线辐照。AZIZ等[103]研究表明,采用1.5—3.5 kGy的γ射线对草莓、杏、李、桃、葡萄、枣、无花果、苹果、梨、桑葚进行辐照处理后,样品中PAT、OTA、AF等多种真菌毒素污染均有显著降低,未经辐照的样品污染概率为辐照样品的5.4倍,但同样不能彻底脱除。有人曾对辐照技术处理后产品的营养水平和安全性提出质疑,FAO/IAEA/WHO联合专家委员会研究小组得出结论:食品总体平均吸收剂量不超过10 kGy时没有毒理学危险,同时营养学上也是安全的。目前许多国家和地区已制定了相关的食品辐照标准[104]。

5.3 生物防治

目前采用的主要生物防治方法为生物竞争抑毒技术和生防微生物及其活性物质抑毒技术,后者在果品上较为常见。细菌和酵母是目前研究最多的生防微生物资源,其作用机理可能是诱导寄主防御系统、分泌分解酶、抵御活性氧伤害、缓解果实被氧化等[105]。目前,不少国家均有生防菌产品用于果品生产或贮藏环节的真菌病害防治,如德国的 Shemer™和Boni-Protect™,西班牙的 Candifruit™,美国的Aspire™和BIOSAVE™,中国的枯草芽孢杆菌等,应用广泛。SPADARO等[106]采用3种拮抗酵母和杀菌剂对4个品种苹果中的扩展青霉和PAT的控制进行研究,发现拮抗酵母和杀菌剂均可不同程度地降低PAT污染浓度,其中AL27的抑菌效果与杀菌剂接近,可使侵染青霉病的金冠苹果在22℃下保存7 d和1℃下保存56 d而不产生PAT。AHMED等[107]证实,Stifenia®和Scala®两种生防菌可显著抑制葡萄真菌病害以及葡萄和酒中OTA的发生,处理后可将OTA含量降低70%—84%。有研究者认为,生物防治可能是未来果品中真菌毒素控制的最具竞争力的技术之一[6,105]。

6 展望

真菌毒素分布广泛,对人和动物健康的潜在危害不容忽视,已引起世界各国的高度关注。果品作为人类最为重要的膳食来源之一,保证其质量安全的重要性日益凸显,精准快速检测技术、风险评估、脱除技术成为今后关注的热点问题。随着国家对果品质量安全科学研究的逐步加强和风险评估的日益强化,中国对果品真菌毒素的研究也在不断深入,但与发达国家相比尚存在较大差距,今后还需从以下几个方面加强相关工作:第一,从果品和毒素种类看,目前研究主要集中在苹果及其制品中的PAT、干果和葡萄及制品中的 OTA上,其他果品和毒素涉及极少,应拓展对其他果品中如链格孢霉毒素、单端孢霉烯族毒素等的相关研究。第二,从毒素产生情况看,目前多为对病原菌的识别和发生规律研究,各毒素产毒与作用机理尚不完全明确,应进一步深入研究。第三,从检测技术看,多集中在对传统的实验室分析技术优化方面,快速检测技术与配套产品的研发不能满足实际需求,可能成为今后的研究重点。第四,从安全性角度看,果品真菌毒素限量标准的制修订研究,建立既符合国际通行规则又具有本国国情的风险评估技术,多种真菌毒素的混合污染[35,84]和联合毒性对产品安全性的影响等,也是今后的重要研究内容。第五,从毒素控制技术看,应基于果品真菌毒素的产生规律、风险评估等基础研究,建立预警防控体系,实现与科学监管、生产指导的对接。

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). [2017-1-6]. Production Crop[EB/OL]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ #data/QC

[2] 李培武, 张奇, 丁小霞, 白艺珍. 食用植物性农产品质量安全研究进展. 中国农业科学, 2014, 47(18): 3618-3632. LI P W, ZHANG Q, DING X X, BAI Y Z. A review of studies on quality and safety of edible vegetable agro-products. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2014, 47(18): 3618-3632. (in Chinese)

[3] YANG J Y, LI J, JIANG Y M, DUAN X W, QU H X, YANG B, CHEN F, SIVAKUMAR D. Natural occurrence, analysis, and prevention of mycotoxins in fruits and their processed products. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2014, 54: 64-83.

[4] BHAT R, SRIDHAR K R, KARIM A A. Microbial quality evaluation and effective decontamination of nutraceutically valued lotus seeds by electron beams and gamma irradiation. Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2010, 79: 976-981.

[5] FERNÁNDEZ-CRUZ M L, MANSILLA M L, TADEO J L. Mycotoxins in fruits and their processed products: Analysis, occurrence and health implications. Journal of Advanced Research, 2010, 1: 113-122.

[6] BARKAI-GOLAN R, PASTER N. Mycotoxins in Fruits and Vegetables. New York: Academic Press, 2008.

[7] FUNG F, CLARK R F. Health effects of mycotoxins: A toxicological overview. Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology, 2004, 42(2): 217-234.

[8] SHEPHARD G S. Impact of mycotoxins on human health in developing countries. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A, 2008, 25(2): 146-151.

[9] ZAIN M E. Impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society, 2011, 15: 129-144.

[10] MEDINA Á, MATEO R, VALLE-ALGARRA F M, MATEO E M, JIMÉNEZ M. Effect of carbendazim and physicochemical factors on the growth and ochratoxin A production of Aspergillus carbonarius isolated from grapes. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007, 119(3): 230-235.

[11] TRUCKSESS M W, SCOTT P M. Mycotoxins in botanicals and dried fruits: A review. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A, 2008, 25(2): 181-192.

[12] GNONLONFIN G J B, ADJOVI Y C, TOKPO A F, AGBEKPONOU E D, AMEYAPOH Y, DE SOUZA C, BRIMER L, SANNI A. Mycobiota and identification of aflatoxin gene cluster in marketed spices in West Africa. Food Control, 2013, 34: 115-120.

[13] VACLAVIKOVA M, DZUMAN Z, LACINA O, FENCLOVA M, VEPRIKOVA Z, ZACHARIASOVA M, HAJSLOVA J. Monitoring survey of patulin in a variety of fruit-based products using a sensitive UHPLC-MS/MS analytical procedure. Food Control, 2015, 47: 577-584.

[14] NTASIOU P, MYRESIOTIS C, KONSTANTINOU S, PAPADOPOULOU-MOURKIDOU E, KARAOGLANIDIS G S. Identification, characterization and mycotoxigenic ability of Alternaria spp. causing core rot of apple fruit in Greece. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2015, 197: 22-29.

[15] WANG M, JIANG N, XIAN H, WEI D Z, SHI L, FENG X Y. A single-step solid phase extraction for the simultaneous determination of 8 mycotoxins in fruits by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 2016, 1429: 22-29.

[16] 王督, 张文, 李培武, 张奇, 张兆威, 丁小霞, 姜俊. 胶体金免疫层析法快速定量分析粮油农产品中黄曲霉毒素 B1. 中国油料作物学报, 2014, 36(4): 529-532. WANG D, ZHANG W, LI P W, ZHANG Q, ZHANG Z W, DING X X, JIANG J. Rapid and quantitative detection of aflatoxin B1in plant grain and oilseeds products using colloid golden immunochromatographic method. Chinese Journal of Oil Crop Sciences, 2014, 36(4): 529-532. (in Chinese)

[17] 孙娟, 李为喜, 张妍, 孙丽娟, 董晓丽, 胡学旭, 王步军. 用超高效液相色谱串联质谱法同时测定谷物中 12种真菌毒素. 作物学报, 2014, 40(4): 691-701. SUN J, LI W X, ZHANG Y, SUN L J, DONG X L, HU X X, WANG B J. Simultaneous determination of twelve mycotoxins in cereals by Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tendem mass spectrometry. Acta Agronomica Sinica, 2014, 40(4): 691-701. (in Chinese)

[18] 王战辉, 米铁军, 沈建忠. 荧光偏振免疫分析检测粮食及其制品中的真菌毒素研究进展. 中国农业科学, 2012, 45(23): 4862-4872. WANG Z H, MI T J, SHEN J Z. Advance in fluorescence polarization immunoassay for the determination of mycotoxins in cereals and related products. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2012, 45(23):4862-4872. (in Chinese)

[19] 张小平, 李元瑞, 师俊玲, 岳田利. 苹果汁中棒曲霉素控制技术研究进展. 中国农业科学, 2004, 37(11): 1672-1676. ZHANG X P, LI Y R, SHI J L, YUE T L. A Review on the Control of Patulin in Apple Juice. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2004, 37(11): 1672-1676. (in Chinese)

[20] 李卫华, 杜利君, 宋欢. 高效液相色谱法测定浓缩苹果汁中棒曲霉毒素. 食品科学, 2007, 28(08): 408- 410. LI W H, DU L J, SONG H. Determination of patulin in apple juice concentrated by high performance liquid chromatography. Food Science, 2007, 28(08): 408- 410. (in Chinese)

[21] 何强, 李建华, 孔祥虹, 乐爱山, 吴双民. 超高效液相色谱-串联质谱法同时测定浓缩苹果汁中的 4种链格孢霉毒素. 色谱, 2010, 28(12): 1128-1131. HE Q, LI J H, KONG X H, YUE A S, WU S M. Simultaneous determ ination of fourAlternariatoxins in apple juice concentrate by ultra performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Chinese Journal of Chromatography, 2010, 28(12): 1128-1131. (in Chinese)

[22] 侯建波, 谢文, 李杰, 沈炜锋, 何建敏. 液相色谱-串联质谱法测定葡萄酒中赭曲霉毒素A. 中国酿造, 2014, 33(5): 146-149. HOU J B, XIE W, LI J, SHEN W F, HE J M. Determination of ochratoxin A in wine by LC-MS/MS. China Brewing, 2014, 33(5): 146-149. (in Chinese)

[23] PASTER N, BARKAI-GOLAN R. Mouldy fruits and vegetables as a source of mycotoxins: part 2. World Mycotoxin Journal, 2008, 4: 385-396.

[24] OSTRY V, SKARKOVA J, RUPRICH J. Occurrence of Penicillium expansum and patulin in apples as raw materials for processing of foods-case study. Mycotoxin Research, 2004, 20(1): 24-28.

[25] SOLIMAN S, LI X Z, SHAO S, BEHAR M, SVIRCEV A M, TSAO R, ZHOU T. Potential mycotoxin contamination risks of apple products associated with fungal flora of apple core. Food Control, 2015, 47: 585-591.

[26] FRIZZELL C, ELLIOTT C T, CONNOLLY L. Effects of the mycotoxin patulin at the level of nuclear receptor transcriptional activity and steroidogenesis in vitro. Toxicology Letters, 2014, 229: 366-373.

[27] SARUBBI F, FORMISANO G, AURIEMMA G, ARRICHIELLO A, PALOMBA R. Patulin in homogenized fruit's and tomato products. Food Control, 2016, 59: 420-423.

[28] MOAKE M, PADILLA-ZAKOUR O, WOROBO R W. Comprehensive review of patulin control methods in foods. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2005, 4(1): 8-21.

[29] PUEL O, GALTIER P, OSWALD I P. Biosynthesis and toxicological effects of patulin. Toxins, 2010, 2(4): 613-631.

[30] PIQUÉ E, VARGAS-MURGA L, GÓMEZ-CATALÁN J, LAPUENTE J, LLOBET J M. Occurrence of patulin in organic and conventional apple-based food marketed in Catalonia and exposure assessment. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2013, 60: 199-204.

[31] ZHOU S M, JIANG L P, GENG C Y, CAO J, ZHONG L F. Patulin induced oxidative DNA damage and p53 modulation in HepG2 cells. Toxicon, 2010, 55: 390-395.

[32] ASAO T, BÜCHI G, ABDEL K M M, CHANG S B, WICK E L, WOGAN G N. Structures of aflatoxins B and G1. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1965, 87(4): 882-886.

[33] JUAN C, ZINEDINE A , J C MOLTÓ, IDRISSI L, MAÑES J. Aflatoxins levels in dried fruits and nuts from Rabat-Salé area, Morocco. Food Control, 2008, 19: 849-853.

[34] IQBAL S Z, ASI M R, JINAP S. Aflatoxins in dates and dates products. Food Control, 2014, 43: 163-166.

[35] BAMBA R, SUMBALI G. Co-occurrence of aflatoxin B1and cyclopiazonic acid in sour lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle) during post-harvest pathogenesis by Aspergillus flavus. Mycopathologia, 2005, 159: 407-411.

[36] International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Some Naturally Occurring Substances, Food Items and Constituents, Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines and Mycotoxins. Lyon, France: IARC, 1993: 56.

[37] International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, France: IARC, 2002: 82.

[38] STARK A A. Mechanisms of action of aflatoxin B1at the biochemical and molecular levels In Microbial Food Contamination (C.L. Wilson and S. Droby, eds). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2001.

[39] LI P W, ZHANG Q, ZHANG W. Immunoassays for aflatoxins. Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2009, 28(9): 1115-1126.

[40] ANDERSEN B, KROGER E, ROBERTS R G. Chemical and morphological segregation of Alternaria arborescens, A. infectoria and A. tenuissima species-groups. Mycological Research, 2002, 106: 170-182.

[41] PERRE E V, DESCHUYFFELEER N, JACXSENS L, VEKEMAN F, HAUWAERT W V D, ASAM S, RYCHLIK M, DEVLIEGHERE F, MEULENAER B D. Screening of moulds and mycotoxins in tomatoes, bell peppers, onions, soft red fruits and derived tomatoproducts. Food Control, 2014, 37: 165-170.

[42] GRECO M, PATRIARCA A, TERMINIELLO L, PINTO V F, POSE G. Toxigenic Alternaria species from Argentinean blueberries. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2012, 154: 187-191.

[43] ANDERSEN B, J SMEDSGAARD, JØRRING I, SKOUBOE P, PEDERSEN L H. Real-time PCR quantification of the AM-toxin gene and HPLC qualification of toxigenic metabolites from Alternaria species from apples. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111: 105-111.

[44] LOGRIECO A, BOTTALICO A, MULE G, MORETTI A, PERRONE G. Epidemiology of toxigenic fungi and their associated mycotoxins for some Mediterranean crops. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2003, 109: 645-667.

[45] VISCONTI A, LOGRIECO A, BOTTALICO A. Natural occurrence of Alternaria mycotoxins in olives: Production and possible transfer into oil. Food Additives and Contaminants, 1986, 4: 323-330.

[46] LÓPEZ P, VENEMA D, DE RIJK T, DE KOK A, SCHOLTEN J M, MOL H G J, DE NIJS M. Occurrence of Alternaria toxins in food products in the Netherlands. Food Control, 2016, 60: 196-204.

[47] SCOTT P, LAWRENCE B, LAU B. Analysis of wines, grape juices and cranberry juices for Alternaria toxins. Mycotoxin Research, 2006, 22: 142-147.

[48] PRELLE A, SPADARO D, GARIBALDI A, GULLINO M L. A new method for detection of five Alternaria toxins in food matrices based on LC-APCI-MS. Food Chemistry, 2013, 140: 161-167.

[49] PANIGRAHI S, DALLIN S. Toxicity of the Alternaria spp metabolites, tenuazonic acid, alternariol, altertoxin-I, and alternariol monomethyl ether to brine shrimp (Artemia salina L) larvae. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 1994, 66(4): 493-496.

[50] LIU G T, QIAN Y Z, ZHANG P, DONG W H, QI Y M, GUO H T. Etiologic role of alternaria-alternata in human esophageal cancer. Chinese Medical Journal Peking, 1992, 105: 394-400.

[51] ZHOU B, QIANG S. Environmental, genetic and cellular toxicity of tenuazonic acid isolated from Alternaria alternata. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2008, 7: 1151-1156.

[52] OSTRY V. Alternaria mycotoxins: An overview of chemical characterization, producers, toxicity, analysis and occurrence in foodstuffs. World Mycotoxin Journal, 2008, 1: 175-188.

[53] BATTILANI P, PIETRI A. Ochratoxin A in grape and wine. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2002, 108: 639-643.

[54] JIANG C M, SHI J L, ZHU C Y. Fruit spoilage and ochratoxin a production by Aspergillus carbonarius in the berries of different grape cultivars. Food Control, 2013, 30: 93-100.

[55] CHULZE S N, MAGNOLI C E, DALCERO A M. Occurrence of ochratoxin A in wine and ochratoxigenic mycoflora in grapes and dried vine fruits in South America. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2006, 111: S5-S9.

[56] PERRE E V, JACXSENS L, LACHAT C, TAHAN F E, MEULENAER B. Impact of maximum levels in European legislation on exposure of mycotoxins in dried products: Case of aflatoxin B1and ochratoxin A in nuts and dried fruits. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2015, 75: 112-117.

[57] ENGELHARDT G, RUHLAND M, WALLNÖFER P R. Occurrence of ochratoxin A in moldy vegetables and fruits analysed after removal of rotten tissue parts. Advances in food sciences, 1999, 21(3-4): 88-92.

[58] ANDREANA MARINO, ANTONIA NOSTRO, CATERINA FIORENTINO. Ochratoxin A production by Aspergillus westerdijkiae in orange fruit and juice. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2009, 132: 185-189.

[59] CLARK H A, SNEDEKER S M. Ochratoxin A: its cancer risk and potential for exposure. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B, 2006, 9(3): 265-296.

[60] STOEV S D. Foodborne mycotoxicoses, risk assessment and underestimated hazard of masked mycotoxins and joint mycotoxin effects or interaction. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2015, 39(2): 794-809.

[61] European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain Related. Statement on Recent Scientific Information on the Toxicity of Ochratoxin A. Parma, Italy. 2010.

[62] LESZKOWIEZY A P, BOEHAROVAT P, CHEMOZEMSKY I N, CASTEGNARO M. Balkan endemic nephropathy and associated urinary tract tumours: A review on aetiological causes and the potential role of myeotoxins. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A, 2002, 19(3): 282-302.

[63] RUCEVIC M, ROSENQUIST T, BREEN L, CAO L L, CLIFTON J, HIXSON D, JOSIC D. Proteome alterations in response to aristolochic acids in experimental animal model. Journal of Proteomics, 2012, 76: 79-90.

[64] TURNER N W, SUBRAHMANYAM S, PILETSKY S A. Analytical methods for determination of mycotoxins: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2009, 632(2): 168-180.

[65] WELKE J E, HOELTZ M, DOTTORI H A, NOLL I B. Quantitative analysis of patulin in apple juice by thin-layer chromatography using a charge coupled device detector. Food Additives and Contaminants: Part A, 2009, 26(5): 754-758.

[66] ELHARIRY H, BAHOBIAL A A, GHERBAWY Y. Genotypic identification of Penicillium expansum and the role of processing on patulin presence in juice. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2011, 49(4): 941-946.

[67] SANTOS E A, VARGAS E A. Immunoaffinity column clean-up and thin layer chromatography for determination of ochratoxin A in green coffee. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2002, 19(5): 447-458.

[68] MYRESIOTIS C K, TESTEMPASIS S, VRYZAS Z, KARAOGLANIDIS G S, PAPADOPOULOU-MOURKIDOU E. Determination of mycotoxins in pomegranate fruits and juices using a QuEChERS-based method. Food Chemistry, 2015, 182: 81-88.

[69] SULYOK M, KRSKA R, SCHUHMACHER R. Application of an LC-MS/MS based multi-mycotoxin method for the semi-quantitative determination of mycotoxins occurring in different types of food infected by moulds. Food Chemistry, 2010, 119: 408-416.

[70] ZWICKEL T, KLAFFKE H, RICHARDS K, RYCHLIK M. Development of a high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry based analysis for the simultaneous quantification of various Alternaria toxins in wine, vegetable juices and fruit juices. Journal of Chromatography A, 2016, http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/ j.chroma.2016.04.066.

[71] 史文景, 赵其阳, 焦必宁. UPLC-ESI-MS-MS结合QuEChERS同时测定柑橘中的4种真菌毒素. 食品科学, 2014, 35(20): 170-174. SHI W J, ZHAO Q Y, JIAO B N. Simultaneous determination of four mycotoxins in citrus fruits by ultra performance liquid chromatographyelectrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry combined with modified QuEChERS. Food Science, 2014, 35(20): 170-174. (in Chinese)

[72] KHARANDI N, BABRI M, AZAD J. A novel method for determination of patulin in apple juices by GC-MS. Food Chemistry, 2013, 141(3): 1619-1623.

[73] JIMÉNEZ M, MATEO R. Determination of mycotoxins produced by Fusarium isolates from banana fruits by capillary gas chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, 1997, 778: 363-372.

[74] MURILLO-ARBIZU M, GONZÁLEZ-PEÑAS E, HANSEN S H, AMÉZQUETA S, ØSTERGAARD J. Development and validation of a microemulsion electrokinetic chromatography method for patulin quantification in commercial apple juice. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008, 46(6): 2251-2257.

[75] MURILLO-ARBIZU M, GONZÁLEZ-PEÑAS E, AMÉZQUETA S. Determination of patulin in commercial apple juice by micellar electrokinetic chromatography. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2008, 46(1): 57-64.

[76] GONZÁLEZ-PEÑAS E, LEACHE C, CERAIN A L, LIZARRAGA E. Comparison between capillary electrophoresis and HPLC-FL for ochratoxin A quantification in wine. Food Chemistry, 2006, 97(2): 349-354.

[77] LUQUE M I, CÓRDOBA J J, RODRÍGUEZ A, NÚÑEZ F, ANDRADE M J. Development of a PCR protocol to detect ochratoxin A producing moulds in food products. Food Control, 2013, 29(1): 270-278.

[78] SCHULLER P L, VAN EGMOND H P, STOLOFF L. Limits and regulations on mycotoxins In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Mycotoxins, 6-8 September 1981 (NaguibK, Naguib M M, Park D L, Pohland A E. eds). Cairo, Egypt: General Organization for Government Printing Offices, 1983.

[79] VAN EGMOND H. Current situation on regulations for mycotoxins. Overview of tolerances and status of standard methods of sampling and analysis. Food Additives and Contaminants, 1989, 6: 139-188.

[80] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Worldwide regulations for mycotoxins in food and feed in 1995. A Compendium. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper, 64, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. 1997.

[81] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Worldwide regulations for mycotoxins in food and feed in 2003. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper, 81, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. 2004.

[82] 中华人民共和国卫生部. 食品安全国家标准: 食品中真菌毒素限量(GB 2761—2011). 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2011. Ministry of Health, People’s Republic of China. National Food Safety Standard: Limits for Mycotoxins in Food (GB 2761—2011). Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2011. (in Chinese)

[83] ANUKUL N, VANGNAI K, MAHAKARNCHANAKUL W. Significance of regulation limits in mycotoxin contamination in Asia and risk management programs at the national level. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, 2013, 21(3): 227-241.

[84] SIROT V, FREMY J-M, LEBLANC J-C. Dietary exposure to mycotoxins and health risk assessment in the second French total diet study. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2013, 5: 1-11.

[85] HAN Z, NIE D X, YANG X L, WANG J H, PENG S J, WU A B. Quantitative assessment of risk associated with dietary intake of mycotoxin ochratoxin A on the adult inhabitants in Shanghai city of P.R. China. Food Control, 2013, 32: 490-495.

[86] RAAD F, NASREDDINE L, HILAN C, BARTOSIK M, PARENT-MASSIN D. Dietary exposure to aflatoxins, ochratoxin Aand deoxynivalenol from a total diet study in an adult urban Lebanese population. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2014, 73: 35-43.

[87] SERRANO A B, FONT G, RUIZ M J, FERRER E. Co-occurrence and risk assessment of mycotoxins in food and diet from Mediterranean area. Food Chemistry, 2012, 135(2): 423-429.

[88] CANO-SANCHO G, MARIN S, RAMOS A J, SANCHIS V. Occurrence of zearalenone, an oestrogenic mycotoxin, in Catalonia (Spain) and exposure assessment. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2012, 50: 835-839.

[89] GUO Y D, ZHOU Z K, YUAN Y H, YUE T L. Survey of patulin in apple juice concentrates in Shaanxi (China) and its dietary intake. Food Control, 2013, 34: 570-573.

[90] PIEMONTESE L, SOLFRIZZO M, VISCONTI A. Occurrence of patulin in conventional and organic fruit products in Italy and subsequent exposure assessment. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2005, 22: 437-442.

[91] AZAIEZ I, FONT G, MAÑES J, FERNÁNDEZ-FRANZÓN M. Survey of mycotoxins in dates and dried fruits from Tunisian and Spanish markets. Food Control, 2015, 51: 340-346.

[92] The Scientific Committee for Food European Commission (SCF). [2016-4-16]. Assessment of dietary intake of Ochratoxin A by the population of EU Member States. [EB/OL]. http://ec.europa.eu/food/ fs/scoop/3.2.7_en.pdf.

[93] KUIPER-GOODMAN T. Food safety: mycotoxins and phycotoxins in perspective. In: Miraglia M, van Egmond H P, Brera C, Gilbert J (Eds.), Mycotoxins and Phycotoxins: Developments in Chemistry, Toxicology and Food Safety. Alakens, Fort Collins, 1998.

[94] World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. 44th Report of the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives, In: Technical Report Series 859. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, 1995.

[95] KUIPER-GOODMAN T, HILTS C, BILLIARD S M, KIPARISSIS Y, RICHARD I D K, HAYWARD S. Health risk assessment of ochratoxin A for all age-sex strata in a market economy. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 2010, 27(2): 212-240.

[96] European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Opinion of the scientific panel on contaminants in the food chain[CONTAM] related to the potential increase of consumer health risk by a possible increase of the existing maximum levels for aflatoxins in almonds, hazelnuts and pistachios and derived products. EFSA, Parma, Intaly. Doi: 10-2903/ j.efsa. 2007.446.

[97] MALMAURET L, PARENT-MASSIN D, HARDY J L, VERGER P. Contaminants in organic and conventional foodstuffs in France. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2002, 19: 524-532.

[98] BERETTA B, GAIASCHI A, GALLI C L, RESTANI P. Patulin in apple-based foods: occurrence and safety evaluation. Food Additives and Contaminants, 2000, 17: 399-406.

[99] BAERT K, KASASE C, DE MEULENAER B, HUYGHEBAERT A. Incidence of patulin in organic and conventional apple juices marketed in Belgium//First International Symposium on Recent Advances in Food Analysis, Prague, Czech Republic, 2013.

[100] NERI F, MARI M, MENNITI AM, BRIGATI S. Activity of trans-2-hexenal against Penicillium expansum in ‘Conference’ pears. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2006, 100: 1186-1193.

[101] GEMEDA N, WOLDEAMANUEL Y, ASRAT D, DEBELLA A. Effect of essential oils on Aspergillus spore germination, growth and mycotoxin production: a potential source of botanical food preservative. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 2014, 4: S373-S381.

[102] 金发忠. 基于我国农产品客观特性的质量安全问题思考. 农产品质量与安全, 2015(3): 3-11. JIN F Z. Consideration on the quality and safety of agricultural products in China based on their objective characteristics. Quality and Safety of Agro-products, 2015(3): 3-11. (in Chinese)

[103] AZIZ N H, MOUSSA L A A. Influence of gamma-radiation on mycotoxin producing moulds and mycotoxins in fruits. Food Control, 2002, 13(4/5): 281-288.

[104] 迟蕾, 哈益明, 王锋. γ射线对赭曲霉毒素A的辐照降解与产物分析. 食品科学, 2010, 31(11): 320-324. CHI L, HA Y M, WANG F. Degradation and product analysis of ochratoxin A induced by γ-irradiation. Food Science, 2010, 31(11): 320-324. (in Chinese)

[105] LIU J, SUI Y, WISNIEWSKI M, DROBY S, LIU Y S. Review: Utilization of antagonistic yeasts to manage postharvest fungal diseases of fruit. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2013, 167(2): 153-160.

[106] SPADARO D, LORÈ A, GARIBALDI A, GULLINO M L. A new strain of Metschnikowia fructicola for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum and patulin accumulation on four cultivars of apple. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2013, 75: 1-8.

[107] AHMED H, STRUB C, HILAIRE F, SCHORR-GALINDO S. First report: Penicillium adametzioides, a potential biocontrol agent for ochratoxin-producing fungus in grapes, resulting from natural product pre-harvest treatment. Food Control, 2015, 51: 23-30.

(责任编辑 赵伶俐)

Progress in Research of Detection, Risk Assessment and Control of the Mycotoxins in Fruits and Fruit Products

LI ZhiXia, NIE JiYun, YAN Zhen, ZHANG XiaoNan, GUAN DiKai, SHEN YouMing, CHENG Yang

(Institute of Pomology, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences/Laboratory of Quality & Safety Risk Assessment for Fruit (Xingcheng), Ministry of Agriculture, Xingcheng 125100, Liaoning)

Fungi are major pathogens to fruit spoilage in the production, storage and transportation, and also are responsible for significant financial losses. In addition to their ability to cause fruit spoilage, some fungi may produce mycotoxins with potential harm to human health. Mycotoxins are a diverse group of toxic secondary metabolites produced by filamentous fungi under appropriate conditions. Followed by pesticide and heavy metal, the mycotoxins are considered as another important risk factor which can directly affect the quality and safety of fruits and fruit products. Numerous studies show that the mycotoxins can cause DNA damage and are harmful to human and animal health even at low concentrations. They caused liver, kidneys and gastrointestinal tractlesions or may be carcinogenic, teratogenic and mutagenic. Therefore, it is important to investigate the occurrence, accurate detection, risk assessment and control technology of mycotoxins in fruit and fruit products. The most common mycotoxins associated with fruits are patulin (PAT), aflatoxins (AF), alternaria toxins and ochratoxin A (OTA) which are respectively classified into 3, 1, 2B and 2B carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Usually, equipments with high standard configurations are needed for mycotoxin detection due to the extremely low concentrations in fruits and their products. Currently the main detection methods for mycotoxins include thin-layer chromatography, high performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, gas chromatography and mass spectrometry, capillary electrophoresis technology, and so on. However, because of the different chemical structure and properties of special mycotoxin, it is incapable to use a standard method for the simultaneous quantitative determination of all mycotoxins. Therefore, it is a research hotspot to screen accurate, efficient and rapid detection methods for mycotoxins. To date, a total of 80 countries and regions have set the mycotoxin limits in fruits and fruit products to protect the health of consumers. It is to be regretted that there were no regulations for Alternaria toxins yet. Risk assessment results based on toxicological data in many countries were shown that dietary intakes of the mycotoxins from fruits and their products were very low in most cases and may not threaten the human health. Although the mycotoxins in fruits and their products could be prevented and degraded by chemical, physical or biological methods, there has not been an effective technology to complete detoxification in infected products. Hence, it is crucial to prevent mycotoxin production in fruits rather than remove. This review summarized the main mycotoxin types, occurrence, toxicities, detection methods, limit standards, risk assessments and control technologies in fruit and fruit products. And finally, the future research directions of fruit mycotoxins were prospected in order to provide a reference for researchers in this field.

fruit and fruit products; mycotoxin; patulin; aflatoxin; alternaria toxin; ochratoxin A; risk assessment

2016-05-13;接受日期:2016-08-01

国家农产品质量安全风险评估重大专项(GJFP2016003)、中国农业科学院科技创新工程项目(CAAS-ASTIP)

联系方式:李志霞,Tel:0429-3598191;Fax:0429-3598185;E-mail:lizhixia@caas.cn。通信作者聂继云,Tel:0429-3598178;Fax:0429-3598185;E-mail:jiyunnie@163.com