两种改性剂对多氯联苯污染土壤协同热脱附影响研究

2016-12-12刘洁赵中华李晓东陈彤陆胜勇严建华岑可法

刘洁,赵中华,李晓东,陈彤,陆胜勇,严建华,岑可法

浙江大学热能工程研究所 能源清洁利用国家重点实验室,杭州 310027

两种改性剂对多氯联苯污染土壤协同热脱附影响研究

刘洁,赵中华,李晓东*,陈彤,陆胜勇,严建华,岑可法

浙江大学热能工程研究所 能源清洁利用国家重点实验室,杭州 310027

采用热脱附技术处理多氯联苯污染土壤已经成为了一种主要的场地修复方式。为提高热脱附效率,降低能耗,以典型电力电容器污染土壤为对象,采用2种改性剂(零价纳米铁和氢氧化钠)研究协同热脱附下多氯联苯的去除效率、分布特性及毒性当量。结果表明纳米铁和NaOH存在的条件下,有效提高了多氯联苯和毒性当量的去除效率,在较低温度下尤其显著,因此添加改性剂能够有效地促进热脱附过程。纳米铁的协同热脱附机理为显著强化了热脱附过程的传质传热,同时伴有一定的脱氯降解。NaOH的添加在较低温度下实现了较强的脱氯降解作用,加氢脱氯机理可用来解释协同热脱附过程中多氯联苯的脱氯反应过程。上述研究结果为多氯联苯污染土壤的场地修复提供理论基础。

多氯联苯;污染土壤;毒性当量;协同热脱附;改性剂

Received 30 November 2015 accepted 30 December 2015

由于具有的生物化学毒性,多氯联苯(polychlorinated biphenyls,简称PCBs)被列为《持久性有机污染物的斯德哥尔摩公约》首批12种特别有害的持久性有机污染物(POPs)之一。从20世纪70年代开始,世界各国陆续停止了PCBs的生产和使用,然而在过去的几十年间,PCBs释放污染周围环境的事件却时有发生,严重威胁着人身健康和生态安全。近年来,我国部分废旧电力电容器封存场地开始发生含PCBs绝缘油泄露的现象[1-3],大面积的土壤受到了PCBs的污染。为了保护现有土地资源,实现长期可持续发展,国家出台了多项政策法规,大力开展污染土壤的修复示范,全面启动重点污染物的源头减量和土壤修复治理工作。因此,污染土壤修复已经成为国际国内学者广泛关注的一大热点问题。

PCBs污染土壤的修复方法有稳定化[4]、溶剂淋洗[5]、生物降解[6]和热脱附[7]等。热脱附技术具有污染物处理范围宽、去除效率高且修复周期短等优点,被普遍应用于有机物污染土壤的处置,已经成为了一种主要的场地修复方式。热脱附过程中的影响因素包括温度[8]、土壤质地[9-10]、脱附时间[11]、初始浓度和载气流速[12]等,其中温度仍然是影响污染物去除效率的主要因素。PCBs在惰性气氛下发生热脱附时,伴随着分子的脱氯和降解[13-14],通过添加改性剂强化热脱附过程,能够有效的促进PCBs的降解和脱氯,提高热脱附效率并降低能耗。

PCBs脱氯的主要因素在于铁化合物、铜化合物及碱性物质[15]。随着纳米技术的发展,高活性的零价纳米铁被应用于各种环境污染物的迁移和脱毒,如氯代有机溶剂、有机氯杀虫剂和PCBs[16-17]。NaOH作为一种典型的碱基化合物,也适用于含氯污染物的处置。碱基催化分解主要过程是通过加热和碱基促进有机氯组分的活化,生成关键中间产物OH-参与加氢脱氯反应[18]。碱基催化分解不仅能够高效去除PCBs[19-20]、PCDD/Fs、氯苯和其他持久性污染物,同时在反应过程中不会生成二恶英污染物[21-22]。

本文以典型电力电容器污染土壤为对象,以提高热脱附效率、降低热脱附能耗为目的,采用纳米铁、氢氧化钠2种代表性改性剂协同处置PCBs污染土壤,探索热脱附过程中PCBs的去除、脱氯及降解,研究协同热脱附关键因素对PCBs浓度水平和分布特性的影响,以期为PCBs污染场地修复提供支撑和依据。

1 材料与方法 (Materials and methods)

1.1 实验材料

实验中的PCBs污染土壤采自于浙江省某废弃电力电容器封存场地,由于含PCBs绝缘油的泄露造成了周围土壤的污染。土壤经风干、研磨和过筛后冷冻保存,土壤粒径是250~420 μm。污染土壤的PCBs初始浓度约为500 μg·g-1,三氯联苯和四氯联苯为主要的同系物。

零价纳米铁购买于上海超微纳米有限责任公司,纳米铁的平均粒径为50 nm,表面积为20 m2·g-1。氢氧化钠(NaOH)购买自国药试剂有限责任公司,含量为96.0%。

1.2 实验方法

1.2.1 土壤样品制备

未加改性剂的土壤称为空白土(blank soil, BS)。将100 mg纳米铁直接加入2.00 g污染土壤中快速混合均匀,得到含纳米铁5%的土壤样品#1。将20 mg NaOH加入2.00 g污染土壤中混合均匀,得到含1% NaOH的土壤样品#2。

1.2.2 实验装置和条件

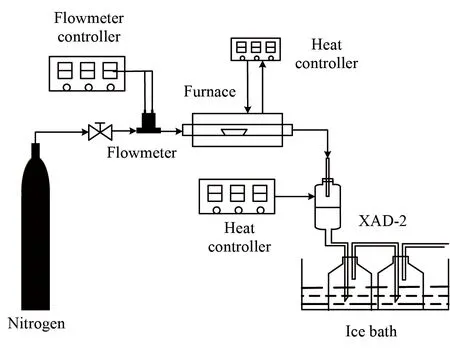

实验台架是一个小型实验室热脱附装置,包括气源(高纯氮,99.9999%)、流量控制装置、程序升温管式炉和气体收集装置,见图1。首先将管式炉升温至一定温度,向石英管中通入400 mL·min-1的氮气,将土壤样品(BS,1#,2#)快速置于石英管中,热脱附温度分别为300、400、500、600 ℃,加热时间为1 h。收集氮气气氛下冷却至室温的土壤样品为固相PCBs,准备预处理和分析。

图1 小型实验室热脱附装置Fig. 1 Bench-scale experimental apparatus

1.2.3 样品提取和分析

在预处理过程中,PCBs样品经索提、旋蒸和溶剂交换后酸洗,依次过多级硅胶柱和弗洛里土柱进行纯化,提取和提纯的详细步骤参见USEPA 1668方法[23]。采用高分辨色质联机HRGC/HRMS (JEOL JMS-800D,日本)分析检测PCBs,色谱柱为DB-5MS(60 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm)。

分析测定包括从一氯联苯(MoCB)到十氯联苯(DeCB)的全部209种PCBs同系物[24-25]。在索提、酸洗和分析前分别加入索提标、净化标和进机标进行同系物的定性定量,索提标的回收率为64%~118%,净化标的回收率为68%~120%,全部符合有关分析标准。2005年世界卫生组织规定的毒性当量因子(toxic equivalency factors, TEFs)用于计算PCBs的毒性当量(toxic equivalency quantity, TEQ)[26]。

1.2.4 数据统计与分析

PCBs的去除效率(removal efficiency, RE)表述了热脱附过程对污染土壤中PCBs的去除能力,计算方法如下:

质量平均氯化度(weight average chlorination degree, CD)描述了土壤样品中PCBs的相对含氯量,计算公式如下:

2 结果(Results)

2.1 改性剂对PCBs浓度的影响

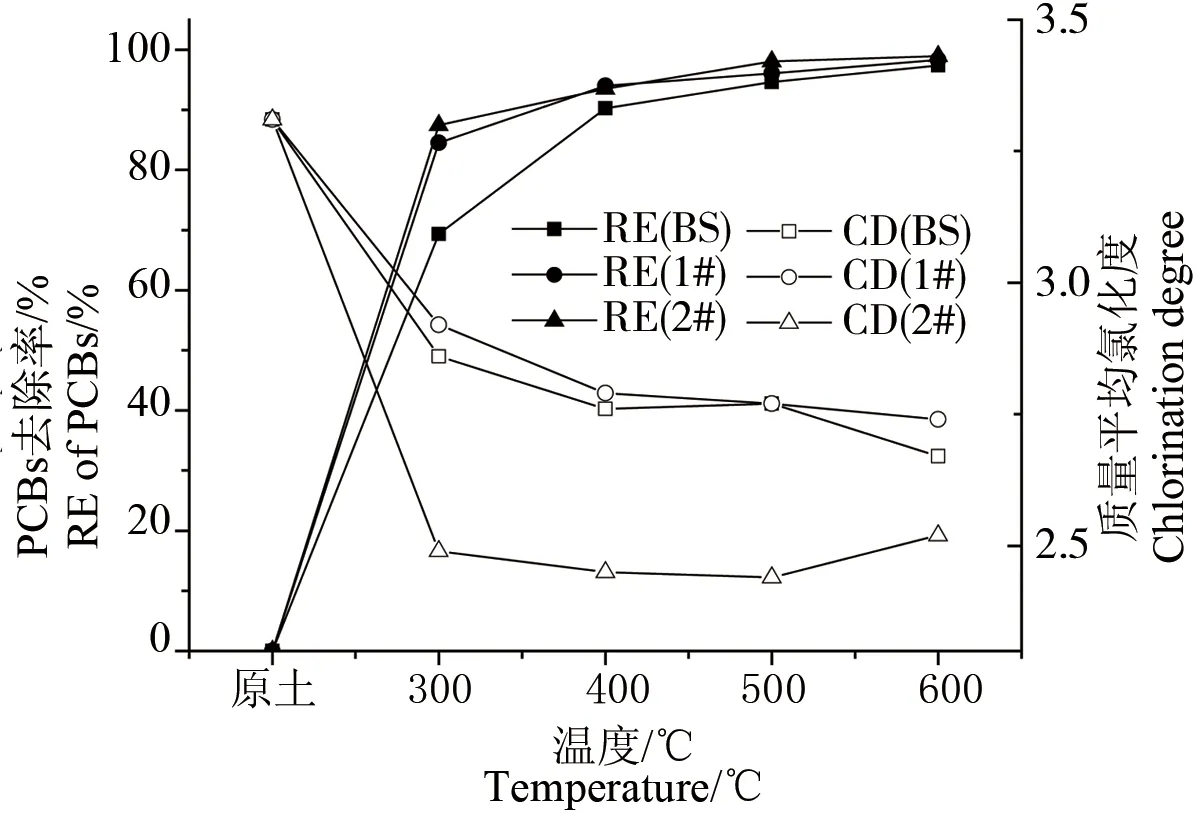

原土中PCBs的浓度为515.5 μg·g-1,显示封存点受到高浓度PCBs污染,具有一定的环境风险。热脱附能够有效的降低污染土壤中PCBs浓度,且随着温度的升高,PCBs浓度逐渐下降。对于空白土,300 ℃下的PCBs去除效率为69.4%,添加改性剂纳米铁后,RE显著增加到84.6%,在NaOH协同作用下RE达到87.4%,结果表明改性剂强化了热脱附过程,促进了PCBs从固相到气相的转移,在较低温度下协同热脱附作用十分显著。提高热脱附温度后,去除效率的差距逐渐减小,在600 ℃下,BS、1#和2#的RE分别为97.4%、98.4%和99.0%。因此,纳米铁和NaOH有效的提高了PCBs的去除效率,尤其在较低温度下,强化了PCBs污染土壤的热脱附过程,显著的降低热脱附能耗。

热脱附是一种复杂的物理化学反应过程,不同温度下PCBs去除机制不同。热脱附温度较低时,物理过程为主要的去除机制,包括土壤颗粒表面附着的PCBs分子受热蒸发,表面扩散和土壤颗粒内部PCBs的内部扩散。高温条件下化学反应为主要的去除机制,PCBs分子发生明显的结构破坏,包括进一步的脱氯和苯环裂解。原土PCBs的质量平均氯化度为3.31,当热脱附温度升高时,氯化度呈下降趋势,主要原因是高温促进了高氯代的PCBs分子脱氯,向低氯代分子转化。土壤样品1#与BS的氯化度无明显差别,表明纳米铁对PCBs氯化度影响不显著,原因是土壤中的纳米铁促进了原有的热脱附反应过程,元素铁参与了PCBs异相脱氯降解反应。与纳米铁不同的是,NaOH的加入显著降低了PCBs的氯化度,在较低温度下就能够实现显著的脱氯和降解。

图2 不同温度下BS、1#和2#中PCBs去除率和氯化度注:BS、1#和2#为空白土、纳米铁改性土和NaOH改性土。Fig. 2 Removal efficiency (RE) and chlorination degree (CD) of PCBs in BS, 1# and 2# at different temperaturesNote: BS, 1# and 2# were blank soil, soil with nZVI and soil with NaOH.

2.2 改性剂对PCBs组成特性的影响

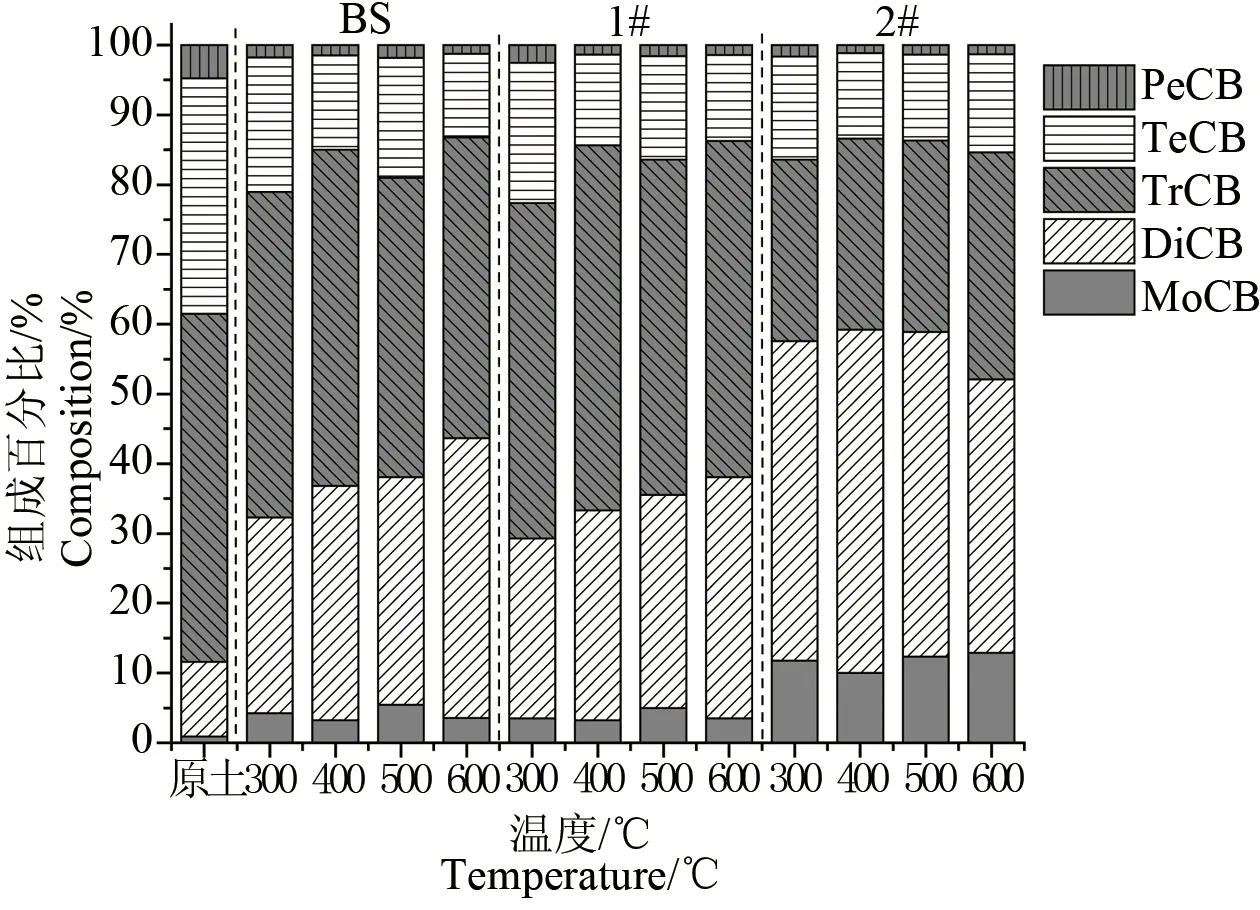

图3是不同温度和改性剂条件下PCBs的组成分布特性。由于六氯代及更高氯代的PCBs总和小于总PCBs的1%,因此仅对一氯到五氯代PCBs进行分析讨论。原土中TrCB(三氯联苯)和TeCB(四氯联苯)为主要的同系物,所占比例分别为49.9%和39.7%,与国产变压器油中PCBs的报道一致。对空白土和纳米铁改性土,随着热脱附温度的升高,低氯代的PCBs(MoCB,DiCB)比例明显增加而高氯代的PCBs(TeCB,PeCB)比例降低,纳米铁的增加对PCBs的组成分布特性无显著差异。

加入NaOH热脱附后的分布特性有显著不同,DiCB(二氯联苯)成为主要同系物,所占比例为39.2%~49.2%,其次为TrCB和TeCB。PCBs主要同系物向低氯代转移表明NaOH在300 ℃下可以促进PCBs分子的脱氯和裂解,实现了较低温度下的表面化学反应。因此,改性剂对PCBs的去除和脱氯均有明显的作用。

图3 不同温度下BS、1#和2#中PCBs的组成分布特性Fig. 3 Composition of PCBs in BS, 1# and 2# at different temperatures

2.3 改性剂对PCBs毒性当量的影响

12种类二恶英多氯联苯(dioxin-like PCBs, dl-PCBs)是与二恶英结构相似且有毒性的PCBs。所有土壤中dl-PCBs同系物分布特性相似,以3种单体所占比例最多,包括2,3',4,4',5-TeCB (#118)、3,3',4,4'-TeCB (#77)、2,3,3',4,4'-PeCB (#105)。原土中dl-PCBs的浓度为10.2 μg·g-1,当温度升高时,dl-PCBs浓度逐渐下降,在600 ℃下达到最小值。600 ℃下,纳米铁和NaOH作用下的dl-PCBs浓度去除效率分别为99.6%和99.8%。比较空白土壤,两者的添加显著提高了有毒PCBs的去除效率。

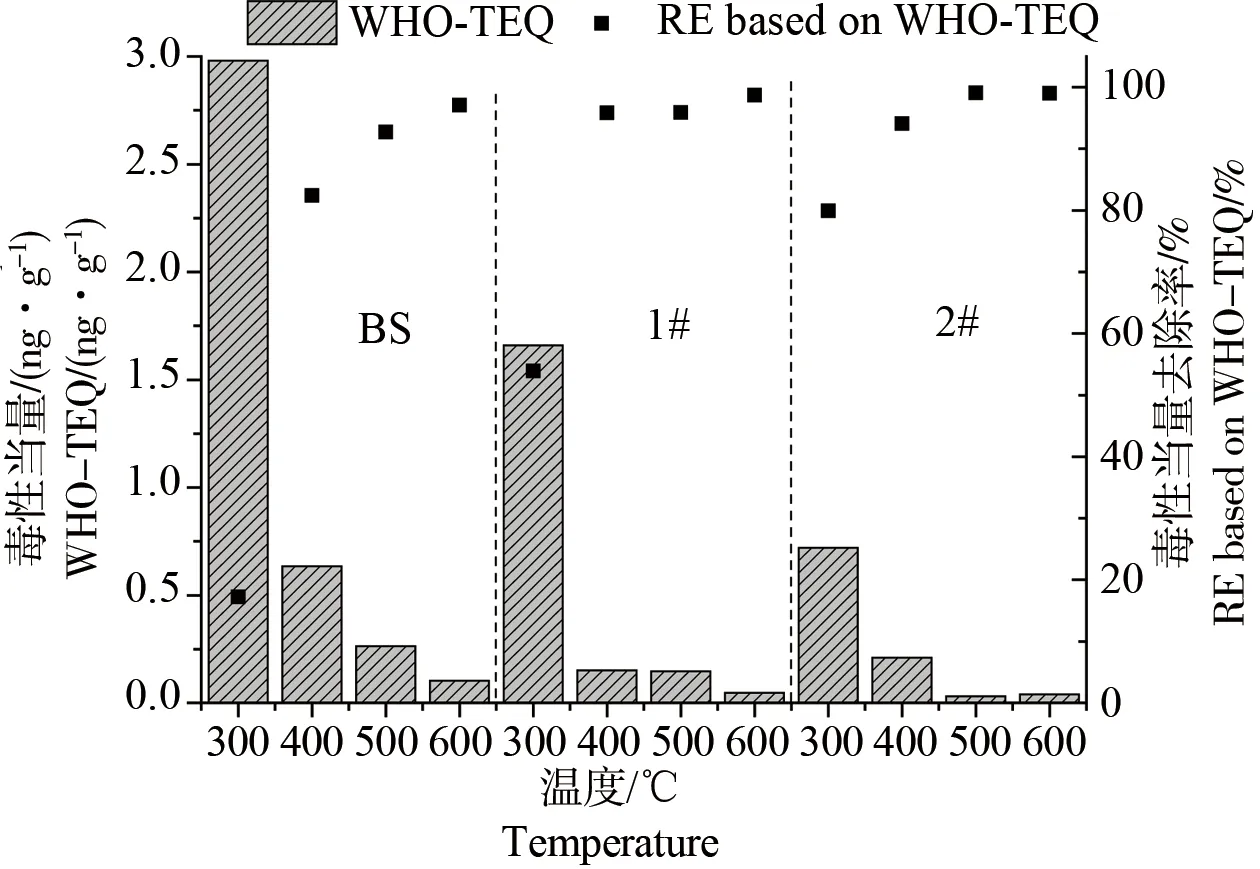

不同温度和改性剂条件下土样BS、1#和2#的毒性当量及去除率见图4。300 ℃下发生热脱附,未加改性剂的土样中毒性当量为2.98 ng TEQ·g-1,毒性当量的去除效率仅为17.2%,相同温度下,1#中WHO-TEQ的RE提高到53.9%,2#中WHO-TEQ的RE达到79.9%,均有效的增加了毒性当量的去除效率,但在高温条件下毒性当量的去除率增加不显著。由此可知,在热脱附过程中,纳米铁和NaOH促进了PCBs的脱毒,在较低温度下协同热脱附作用更为显著。

图4 不同温度下BS、1#和2#的PCBs毒性当量及其去除效率Fig. 4 WHO-TEQ and RE based on WHO-TEQ in BS, 1# and 2# at different temperatures

2.4 协同热脱附机理研究

纳米铁的加入促进了原有热脱附的反应过程,与未添加改性剂土壤相比,氯化度下降趋势和组成分布特性接近,去除效率有明显增加,可能的原因是纳米铁显著强化了热脱附的传质传热过程,在高温条件下伴有一定的脱氯降解作用,脱氯反应机制[27-28]见公式1。参加反应的氢自由基有可能来自于土壤中的杂质,水分子也可能成为质子供体[29]。文献[30-31]研究了PCBs在纳米铁表面发生的脱氯反应途径,氯原子在对位和间位上的脱氯反应比在邻位上的反应更快。

Fe0+C12H(10-n)Cln+H*→Fe2++C12H(11-n)Cl(n-1)+Cl-

(1)

NaOH的添加在较低温度下实现了较强的脱氯降解作用,氯化度随温度影响不显著,表明PCBs分子去除机理以脱氯降解为主,加氢脱氯机制可用来解释碱基催化分解过程中PCBs的脱氯[18,32]。在碱基、碳基催化剂和氢质子供体存在的条件下,有机氯化合物被破坏和分解,产物有脱氯有机物、碱基氯化合物和水[33]。氢自由基可能来自于热脱附过程中PCBs的分解产物,碱基通过减弱C-Cl键能来活化PCBs分子,在碱基催化分解反应中起重要作用。C12H10-nCln+NaOH+2H*→C12H11-nCln-1+NaCl+H2O (2)

3 讨论(Discussion)

本文探索性的研究了零价纳米铁和氢氧化钠两种改性剂对热脱附过程的影响,包括PCBs去除效率、组成分布特性及毒性当量,分析2种添加剂在热脱附过程中的协同机制。结果表明纳米铁提高了PCBs的去除效率,降低了PCBs毒性当量,协同热脱附作用在低温条件下更为显著,但氯化度和组成分布特性与未添加改性剂土壤接近,表明纳米铁显著强化了热脱附过程的传质传热,同时伴有一定的脱氯降解。NaOH有效提高了PCBs去除效率,降低了毒性当量,同时对氯化度和组成分布特性的影响亦十分显著,表明NaOH的添加在较低温度下实现了较强的脱氯降解作用,PCBs分子去除机理以脱氯降解为主,加氢脱氯机理可用来解释碱基催化分解过程中PCBs的脱氯反应过程。

致谢:谨以此文向傅家谟院士致以崇高的敬意!

[1] Xing Y, Lu Y, Dawson R W, et al. A spatial temporal assessment of pollution from PCBs in China [J]. Chemosphere, 2005, 60(6): 731-739

[2] 陈来国, 蔡信德, 黄玉妹, 等. 废弃电容器封存点多氯联苯的含量和分布特征[J]. 中国环境科学, 2008, 28(9): 833-837

Chen L G, Cai X D, Huang Y M, et al. Concentration and distribution of PCBs in one storage site of used capacitors [J]. Chinese Journal of Environmental Science, 2008, 28(9): 833-837 (in Chinese)

[3] 郑群雄, 徐小强, 马军, 等. 废旧电容器封存点土壤中多氯联苯的残留特征[J]. 岩矿测试, 2011, 30(6): 699-704

Zheng Q X, Xu X Q, Ma J, et al. Residue characteristics of polychlorinated biphenyls in soils from a storage site of used capacitors [J]. Chinese Journal of Rock and Mineral Analysis, 2011, 30(6): 699-704 (in Chinese)

[4] 彭伟, 谯华, 方振东, 等. 多氯联苯污染土壤修复技术研究进展[J]. 化学与生物工程, 2014, 31(6): 9-14

Peng W, Qiao H, Fang Z D, et al. Remediation technologies of PCBs-contaminated soil [J]. Chinese Journal of Chemistry and Bioengineering, 2014, 31(6): 9-14 (in Chinese)

[5] Oshita K, Takaoka M, Kitade S, et al. Extraction of PCBs and water from river sediment using liquefied dimethyl ether as an extractant [J]. Chemosphere, 2010, 78(9): 1148-1154

[6] Huesemann M H, Hausmann T S, Fortman T J, et al. In situ phytoremediation of PAH- and PCB-contaminated marine sediments with eelgrass (Zostera marina) [J]. Ecological Engineering, 2009, 35(10): 1395-1404

[7] Aresta M, Dibenedetto A, Fragale C,et al. Thermal desorption of polychlorobiphenyls from contaminated soils and their hydrodechlorination using Pd- and Rh-supported catalysts [J]. Chemosphere, 2008, 70(6): 1052-1058

[8] Tse K K, Lo S L. Desorption kinetics of PCP-contaminated soil: Effect of temperature [J]. Water Research, 2002, 36(1): 284-290

[9] Lee D H, Cody R D, Kim D J, et al. Effect of soil texture on surfactant-based remediation of hydrophobic organic-contaminated soil [J]. Environment International, 2002, 27(8): 681-688

[10] Qi Z F, Chen T, Bai S H, et al. Effect of temperature and particle size on the thermal desorption of PCBs from contaminated soil [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2014, 21(6): 4697-4704

[11] Falciglia P P, Giustra M G, Vagliasindi F G. Low-temperature thermal desorption of diesel polluted soil: Influence of temperature and soil texture on contaminant removal kinetics [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 185(1): 392-400

[12] Risoul V, Renauld V, Trouve G, et al. A laboratory pilot study of thermal decontamination of soils polluted by PCBs. Comparison with thermogravimetric analysis [J]. Waste Management, 2002, 22(1): 61-72

[13] Weber R, Takasuga T, Nagai K, et al. Dechlorination and destruction of PCDD, PCDF and PCB on selected fly ash from municipal waste incineration [J]. Chemosphere, 2002, 46(9-10): 1255-1262

[14] Misaka Y, Yamanaka K, Takeuchi K, et al. Removal of PCDDs/DFs and dl-PCBs in MWI fly ash by heating under vacuum [J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 64(4): 619-627

[15] Weber R, Nagai K, Nishino J, et al. Effects of selected metal oxides on the dechlorination and destruction of PCDD and PCDF [J]. Chemosphere, 2002, 46(9-10): 1247-1253

[16] Wang C B, Zhang W X. Synthesizing nanoscale iron particles for rapid and complete dechlorination of TCE and PCBs [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1997, 31(7): 2154-2156

[17] Zhang W X. Nanoscale iron particles for environmental remediation: An overview [J]. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, 2003, 5(3-4): 323-332

[18] Kawahara F K, Michalakos P M. Base-catalyzed destruction of PCBs-New donors, new transfer agents/catalysts [J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 1997, 36(5): 1580-1585

[19] Taniguchi S, Hosomi M, Murakami A, et al. Chemical decomposition of toxic organic chlorine compounds [J]. Chemosphere, 1996, 32(1): 199-202

[20] Taniguchi S, Miyamura A, Ebihara A, et al. Treatment of PCB-contaminated soil in a pilot-scale continuous decomposition system [J]. Chemosphere, 1998, 37(9-12): 2315-2326

[21] Chen A S C, Gavaskar A R, Alleman B C, et al. Treating contaminated sediment with a two-stage base-catalyzed decomposition (BCD) process: Bench-scale evaluation [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 1997, 56(3): 287-306

[22] Xiao Y, Jiang J G. Base-catalyzed decomposition of hexachlorobenzene: Effect on dechlorination efficiency of different hydrogen donors, alkalis and catalysts [J]. RSC Advances, 2014, 4(30): 15713-15719

[23] USEPA. Method 1668B. Chlorinated Biphenyl Congeners in Water, Soil, Sediment, Biosolids, and Tissue by HRGC/HRMS [S]. Washington DC: USEPA Press, 2008

[24] Frame G M. A collaborative study of 209 PCB congeners and 6 Aroclorson 20 different HRGC columns.1. Retention and coelution database [J]. Fresenius Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 1997, 357(6): 701-713

[25] Chen T, Li X D, Yan J H, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls emission from a medical waste incinerator in China [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2009, 172(2-3): 1339-1343

[26] Van den Berg M, Birnbaum L S, Denison M, et al. The 2005 World Health Organization reevaluation of human and mammalian toxic equivalency factors for dioxins and dioxin-like compounds [J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2006, 93(2): 223-241

[27] Matheson L J, Tratnyek P G. Reductive dehalogenation of chlorinated methanes by iron metal [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1994, 28(12): 2045-2053

[28] Wu B Z, Chen H Y, Wang S J, et al. Reductive dechlorination for remediation of polychlorinated biphenyls [J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 88(7): 757-768

[29] Chuang F W, Larson R A, Wessman M S. Zero-valent iron-promoted dechlorination of polychlorinated biphenyls [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 1995, 29(9): 2460-2463

[30] Lowry G V, Johnson K M. Congener-specific dechlorination of dissolved PCBs by microscale and nanoscalezerovalent iron in a water/methanol solution [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2004, 38(19): 5208-5216

[31] Venkatachalam K, Arzuaga X, Chopra N, et al. Reductive dechlorination of 3,3',4,4'-tetrachlorobiphenyl (PCB77) using palladium or palladium/iron nanoparticles and assessment of the reduction in toxic potency in vascular endothelial cells [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2008, 159(2-3): 483-491

[32] Akzinnay S, Bisaro F, Cazin C S J. Highly efficient catalytic hydrodehalogenation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) [J]. Chemical Communications, 2009, 38: 5752-5753

[33] Takada M, Uchida R, Taniguchi S, et al. Chemical dechlorination of PCBs by the base catalyzed decomposition process. Organohalogen Compounds [C]. 1997, 31: 435-440

◆

Effect of Two Additives on Thermal Desorption of PCBs Contaminated Soil

Liu Jie, Zhao Zhonghua, Li Xiaodong*, Chen Tong, Lu Shengyong, Yan Jianhua, Cen Kefa

State Key Laboratory of Clean Energy Utilization, Institute for Thermal Power Engineering, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China

Thermal desorption has become an effective site remediation technology for treating polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) contaminated soil. In order to increase efficiency and reduce energy consumption, synergetic thermal desorption of PCB-contaminated soil collected from typical soil contaminated by waste capacitors and transformers was studied. By two additives (nano zerovalent iron and sodium hydroxide) addition, removal efficiency (RE), composition and toxic equivalency quantity (TEQ) of PCBs were investigated. The results showed nano zerovalent iron and NaOH effectively increased the RE of PCBs and TEQ, especially at lower temperature, thus additives strengthened the process of thermal desorption. The synergetic mechanism of nano zerovalent iron on thermal desorption is significant promotion on mass and heat transfer process, accompanied by dechlorination and decomposition. The addition of NaOH realized strong dechlorination and destruction at lower temperature. The hydrogenation/dechloriantion mechanism is proposed to explain the PCBs pathways during the thermal desorption. The results presented in this study will provide theoretical basis for site remediation of PCBs contaminated soil.

PCBs; contaminated soil; TEQ; synergetic thermal desorption; additive

10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20151130019

国家高技术研究发展计划(863)项目(2009AA061304)

刘洁(1985-),女,博士研究生,研究方向为固体废弃物热处置,E-mail:liujie2090@zju.edu.cn

*通讯作者(Corresponding author), E-mail: lixd@zju.edu.cn

2015-11-30 录用日期:2015-12-30

1673-5897(2016)2-636-06

X171.5

A

简介:李晓东(1966-),男,工程热物理博士,教授,主要研究方向废弃物热处理及污染物削减控制。

刘洁, 赵中华, 李晓东, 等. 两种改性剂对多氯联苯污染土壤协同热脱附影响研究[J]. 生态毒理学报,2016, 11(2): 636-641

Liu J, Zhao Z H, Li X D, et al. Effect of two additives on thermal desorption of PCBs contaminated soil [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2016, 11(2): 636-641 (in Chinese)