12-冠-4对非质子Li-O2电池氧电极的影响

2016-11-18王晓晨王英明白若鹏刘艳芳丽陆君涛

王晓晨 王英明 刘 威 白若鹏 刘艳芳 肖 丽陆君涛 庄 林

(武汉大学化学与分子科学学院,化学电源材料与技术湖北省重点实验室,武汉 430072)

12-冠-4对非质子Li-O2电池氧电极的影响

王晓晨 王英明 刘 威 白若鹏 刘艳芳 肖 丽*陆君涛 庄 林

(武汉大学化学与分子科学学院,化学电源材料与技术湖北省重点实验室,武汉 430072)

Li-O2电池放电产物Li2O2由于在有机溶剂中溶解度较差,会堵塞气体通道,这是Li-O2电池面临的一个主要挑战。在本工作中,我们选择12-冠-4做为添加剂捕获Li+,来研究其对氧电极放电产物溶解性的影响,并采用了多种电化学表征方法,包括循环伏安法和旋转圆盘电极等。结果显示,仅仅添加5%的12-冠-4就能明显提高氧还原产物的稳定性,并减少固体Li2O2的生成。结合软硬酸碱和第一性原理计算对上述实验结果进行了解释。

Li-O2电池; 氧电极; 冠醚; 软硬酸碱理论

1 Introduction

The concept of aprotic Li-air batteries has been introduced by Abraham and Jiang in 1996, and has attracted much attention because of its high theoretical energy density1,2. In recent years, many important progress, such as the concept of aqueous Li-air batteries proposed by Zhou and Wang3and the charge-discharge cyclibility of aprotic Li-air batteries achieved by Bruce's group4, has been reported in the literature5–16. In addition to Liair battery, now Na-air and K-air batteries have emerged, which also rely on the O2-electrode in aprotic solvents17,18.

For aprotic Li-air batteries, there are some fundamental problems in the O2-electrode, especially the low conductivity and poor solubility of the discharge product (Li2O2)19. Since Li2O2is hardly soluble in organic electrolyte solutions, it can precipitate in the pores of the porous carbon-based O2-electrode, block the O2transportation channel, and may thus eventually end the cell life20.

To avoid the above problems, the common strategy is to adjust the structure of the oxygen electrode, such as to control the size of the pores in the electrode to accommodate more solid products8; or to manipulate the size and shape of Li2O2. Recent research shows that trace amounts of H2O can dissolve LiO2and change the morphology and structure of Li2O221. Another strategy is to use aqueous electrolyte instead of aprotic electrolyte, for the discharge product will become the soluble LiOH instead of the insoluble Li2O222–24. However, there are some severe problems that must be addressed for a water-stable lithium electrode (WSLE)22. The third strategy is to use additives to promote the dissolution of the discharge products. For example, complexing cations19, strong Lewis acids (C6F5)3B, or sp3borate esters have been added to the electrolyte to dissolve Li2O2, taking the advantage of their strong interaction between the anions in the electrolyte24–26. A conceptually molecular peroxide dianion adduct that can stabilizehas also been employed as a potential soluble source of

Given the above interest in additives for the Li-air battery, we intend to further investigate the effect of additives on the O2-electrode. We made a hypothesis that an additive having strong interaction with Li+may weaken the interaction between Li+and the anions in the electrolyte, which may thus result in soluble products. An additive that interacts strongly with Li+is 12-crown-4, also called 1,4,7,10-tetraoxacyclododecane. We investigated the change made by adding different amount of 12-crown-4 to the electrolyte, and found that, with a small amount of 12-crown-4, theproduct can be stabilized, while further increasing the concentration of 12-crown-4 in the electrolyte will decrease the stability ofCombined with ab initio calculations, we employed the hard-soft-acid-base (HSAB) theory to explain such experimental observations.

2 Experimental

2.1 Cyclic voltammetry (CV)

Cyclic voltammetry was carried out in an O2saturated dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) (HPLC, 99.5%, hydrous) solvent and anhydrous lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) was used as supporting electrolyte (0.05 mol·L–1). A glassy carbon (GC)rotating disc electrode (4.5 mm in diameter) was used as the working electrode. An Ag/Ag+electrode, filled with DMSO containing 5 mmol·L–1AgNO3and 0.05 mol·L–1LiPF6, was employed as the reference electrode. The CV curves were recorded at a scan rate of 5 mV·s–1. The concentration of 1,4,7,10-tetraoxacyclododecane (12-crown-4, 98%, Alfa Aesar)was varied as described below. The potentiostat was a CHI660 electrochemical station. All experiments were conducted at room temperature.

2.2 Oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) evaluation

ORR evaluation was carried out under the same condition as CV measurements. The rotating ring-disc electrode (RRDE)system consisted of a PINE rotator (E6 Series). The ORR curves of the GC disc-electrode were recorded at a scan rate of 50 mV·s–1, and the potential of the ring-electrode (Pt ring) was hold at –0.2 V (vs Ag/Ag+).

2.3 Ab initio calculation

Ab initio calculations were performed at the level of B3LYP/6-31G(d, p) using GAMESS28for the ground state geometry. In order to identify the possible charge transfer, the Mulliken charge population analysis was carried out thereafter.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Influence of 12-crown-4 on the CV behavior

Cyclic voltammetry is able to study the oxygen redox couple in Li+containing electrolyte29. It is generally accepted that the reactions occurring on CV sweeps follow these mechanisms(reactions (rxn1–7): On the cathodic sweep, the first reaction is the reduction of O2to LiO2(rxn1, Epeakat –1.25 V (vs Ag/Ag+)in DMSO, the same below), and LiO2is further decomposed/reduced to form Li2O2(rxn2/3, –1.57 V)29. Rxn4 will proceed with lower cathodic potential. On the return anodic sweep, the first reaction is the oxidation of LiO2to O2(rxn5, –0.95 V)29, and then Li2O2is decomposed to form O2(rxn6, –0.45 V). Rxn7will proceed if there is Li2O formed30. As an intermediate, LiO2is quite unstable upon scanning. In order to observe the oxidation current of LiO2, two conditions are required: firstly, the solvent should not react with it; secondly, the scan rate on the return anodic sweep should be fast enough to avoid the reactions of rxn2 and rxn3.

Cathodic

Anodic

DMSO is chosen as the solvent in the present work, for it would not consume LiO230. As shown in Fig.1, the CV curve without adding 12-crown-4 ether is shown in black, where no oxidation peak of LiO2(at –0.9 V) is observed when the scan rate is as slow as 5 mV·s–1. It can be observed more clearly from the inset of Fig.1A, no peak current was found near –0.9 V. Meanwhile, the oxidation peak of Li2O2(P2, –0.45 V) is ob-vious, which demonstrates that LiO2has enough time to convert to Li2O2upon cathodic sweeping under this condition.

However, by adding 5% (as a percentage of Li+concentration) of 12-crown-4 ether, P1 referring to the oxidation of LiO2(at –0.9 V) increased sharply, while P2 declined, indicating that 5% of 12-crown-4 ether can strongly improve the stability of the LiO2and reduce the formation proportion of Li2O2. The peak current of P1 does not increase by further adding of 12-crown-4 ether (from 10% to 30%), and the peak current of P2 decreases gradually with increasing the concentration of 12-crown-4 ether.

The relationship between the concentration of 12-crown-4 ether and the peak currents of P1 and P2 is shown in Fig.1B. By increasing the concentration of 12-crown-4 from 0 to 50%, the peak current of P1 and P2 will change accordingly. Only 1% of 12-crown-4 ether is sufficient to make a difference to the peak currents of P1 and P2. The increase of the peak current of P1 indicates that the stability of LiO2is improved. The highest peak current of P1 is observed with 5% of 12-crown-4 ether, further adding 12-crown-4 ether will slightly decrease the peak current of P1. Meanwhile, the peak current of P2 decreases continuously by increasing the concentration of 12-crown-4 ether, suggesting that the formation of Li2O2was gradually inhibited.

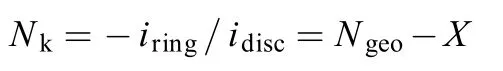

3.2 Determine Nkby RRDE

Rotating ring disc electrode (RRDE) is a more precise way to observe the stability change ofupon adding 12-crown-4 ether. To do so, the collection efficiency, Nk, should be calculated through RRDE method31,32. Nkis the absolute ratio of the ring current to the disc current, which can be described quantitatively by the following equation33,34

where Ngeois the geometrical collection efficiency of the RRDE, corresponding to the fraction of a species electrochemically generated at the disc that will be detected at the ring in the absence of side-reactions with the electrolyte. For our RRDE electrode, Ngeo= 0.20. X is the item caused by the consumption of the species through reacting with the electrolyte. In the present work, X should be caused by the reaction ofin the electrolyte through reactions rxn2 and rxn3. Thus the amount ofconsumed will depend on its effective transport time, Ts, between the disc and the ring. The longer transport time will lead to an increase in the consumption ofand a decrease in theoxidation current at the ring. Thus the variation of Nkwith the electrode rotation rate (ω) can reflect the stability ofThe lower the ω, the longer the transport time, and the Nkwill decrease with ω, ifis not stable in the electrolyte. In contrast, if theis very stable in the electrolyte, Nkwill not change with ω.

In the present work, we performed RRDE measurements in electrolyte containing 0% and 10% of 12-crown-4 ether, at a sweep rate of 50 mV·s–1and rotation rates ranging from 100 to 2500 r·min–1. The ring was set at a potential at which the electro-oxidation ofis diffusion limited (Ering= –0.2 V, at the positive potential limit used in Fig.1A).

Fig.2 Disc and ring currents recorded at 50 mV·s-1in O2saturated DMSO with 0.05 mol·L-1LiPF6at electrode rotation rates between 100 and 2500 r·min-1and continuously holding the Au ring at -0.2 V (vs Ag/Ag+)

The variation of Nkwith the electrode rotation rate is plotted in the insert of Figs.2A and 2B, where the trends are quite different depending on the concentration of 12-crown-4 ether. Without 12-crown-4, Nkdecreases with ω. Specifically, Nkis on the whole not changed with the rotation rates from 900 to 2500 r·min–1, but rapidly decreases to 0.17 at 400 r·min–1, and further decreases to 0.04 at 100 r·min–1. This is becauses the longer transport time at lower rotation rates increases the reaction time ofthrough reactions rxn2 and rxn3, so the concentration ofoxidized at the ring electrode becomes lower. All values of Nkare smaller than the electrode's Ngeo(0.20), due to the consumption ofIn contrast, Nkalmost remains constant with the electrolyte containing 10% of 12-crown-4 ether, with only a slightly decrease at 100 r·min–1, which indicates littlewas consumed through reactions rxn2 and rxn3 in this system. Thus we can infer that theis much more stable in the electrolyte containing certain amount of 12-crown-4 ether.

3.3 Understanding the stability change ofbased on Person′s HSAB theory

In Abraham′s work29, Pearson′s HSAB theory was used to explain the stabilization ofin tetrabutylammonium (TBA+) solution, it is also applicable to explain the stability change ofobserved in this work. The cation in the electrolyte is Li+, an alkali metal ion with a small radius, which is a hard acid. The anions present in the electrolyte in this study includeand those generated electrochemically, i.e.,Within the four anions in the electrolyte, the first one has little interaction with Li+, which will not be discussed. For the other three electrochemically generated anionshas a relatively large radius and low charge density, which is a moderately soft base; while the other two are moderately hard base. According to HSAB theory, hard acids prefer hard bases and soft bases prefer soft acids35, thus the hard Li+with a high affinity for hard Lewis bases stabilizedwill be not stable and quickly convert tothrough reactions rxn2 and rxn3. When certain amount of 12-crown-4 ether is added to the system, Li+will be captured by it, thus the Lewis acidity of Li+is decreased with increasing its radius through coordinating with 12-crown-4 to form Li+-(crown ethers). As a result, theformed in rxn1 will have an increased affinity for these Li+-(crown ethers), and was stabilized in solution.

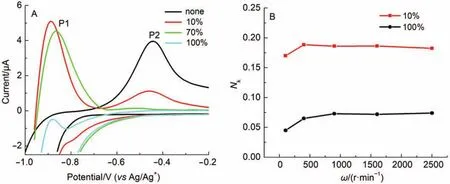

3.4 Superoxide becoming unstable with high concentration of 12-crown-4 ether

As the concentration of 12-crown-4 ether increased above 5%, the peak currents of P1 and P2 were both decreased as shown in Fig.1B, indicating thatwas consumed besides reactions rxn2 and rxn3. The decreasing of the peak current was even more evident when the concentration of 12-crown-4 ether was higher than 50%. When the concentration was increased to 70%, the peak current of P1 slightly decreased with the peakpotential shifting to the positive direction; while the peak current of P2 was almost undetectable (Fig.3A), which means that nearly no Li2O2was formed during the cathodic sweeping through reactions rxn2 and rxn3. By further increasing the concentration of 12-crown-4 ether to 100%, the peak current of P1 decreased to 0 mA, which indicates thatis significantly consumed by some other reactions. The determination of Nkby RRDE experiments also gave the same result. The trends of Nkobtained with the various rotation rate are similar for electrolyte containing 10% and 100% 12-crown-4 ether, but the values are quite different. Nkwas 2.5 times larger in electrolyte containing 10% of 12-crown-4 ether in all rotation rates than that in electrolyte containing 100% of 12-crown-4 ether, which also indicates theis extremely unstable in high concentration of 12-crown-4 ether (Fig.3B).

Fig.3 Cyclic voltammograms recorded in O2saturated DMSO with 0.05 mol·L-1LiPF6at 5 mV·s-1

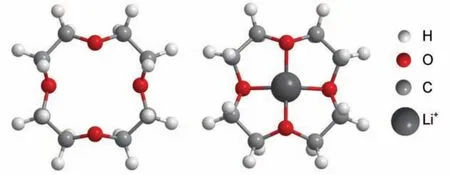

The side reactions consumingother than reactions rxn2 and rxn3 may be attributed to the reaction betweenand 12-crown-4 ether. According to the research of Bruce's group, ether-based electrolytes are unstable with reduced O2species36. As a kind of ether, 12-crown-4 would also be unstable in the electrolyte containing electrochemically generatedgenerated through reaction rxn1 will either disproportionate or reduce to Li2O2, or uptake a proton from 12-crown-4 ether to form an alkyl radical, and leads to the oxidative decomposition reactions to form H2O, CO2, lithium formate, and lithium acetate37. In fact, the 12-crown-4 ether can become more attackable by upon coordinating with Li+([Li]+) according to theoretical calculations. Sinceis a weak nucleophile, it prefers to attack species containing C-atom with lower charge density. The optimized geometrical structures of 12-crown-4 ether with/without Li+are shown in Fig.4. According to ab initio calculations, by coordinating with Li+to form [Li]+, the Mulliken charge population of C-atom in 12-crown-4 has increased from–0.102e to –0.062e (Table 1). When the concentration of [Li]+is low,can be stabilized according to HSBA theory; when the concentration of [Li]+is further increased, there will be more chance for theto attack the C-atom of 12-crown-4, thus its stability will decrease again.

4 Conclusions

In this work, the effects of 12-crown-4 ether on the oxygen electrode of lithium-air batteries were studied. CV and RRDE measurements suggested that 12-crown-4 ether can strongly improve the stability of the reduction productand inhibit the formation of solid Li2O2. However, excess 12-crown-4 etherwill lower the stability ofby consuming

through chemical reactions. The present work has furthered our understanding of the electrode reaction, and provided new insights for improving the performance of Li-air battery.

Fig.4 Optimized geometrical structures of 12-crown-4 ether with and without Li+

Table 1 Ab initio calculations on Mulliken charge population of atoms in 12-crown-4 with and without Li+

(1)Abraham, K. M.; Jiang, Z. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1996, 143, 1. doi: 10.1149/1.1836378

(2)Girishkumar, G.; McCloskey, B.; Luntz, A. C.; Swanson, S.;Wilcke, W. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 1, 2193.

(3)Wang, Y. G.; Zhou, H. S. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 358. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.06.109

(4)Ogasawara, T.; Debart, A.; Holzapfel, M.; Novak, P.; Bruce, P. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1390. doi: 10.1021/ja056811q

(5)Leskes, M.; Drewett, N. E.; Hardwick, L. J.; Bruce, P. G.;Goward, G. R.; Grey, C. P. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2012, 51, 8560. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202183

(6)Choi, N.; Chen, Z. H.; Freunberger, S. A.; Ji, X. L.; Sun, Y.;Amine, K.; Yushin, G.; Nazar, L. F.; Cho, J.; Bruce, P. G. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2012, 51, 9994. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201429

(7)Yoshino, A. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2012, 51, 5798. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105006

(8)Wang, Z. L.; Xu, D.; Xu, J. J.; Zhang, L. L.; Zhang, X. B. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 3699. doi: 10.1002/adfm.v22.17

(9)Shao, Y. Y.; Ding, F.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Park, S.;Zhang, J. G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 987. doi: 10.1002/adfm.v23.8

(10)Park, M.; Sun, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Cho, J. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 2, 780.

(11)Cao, R. G.; Lee, J.; Liu, M. L.; Cho, J. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012,2, 816.

(12)Oh, S. H.; Nazar, L. F. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 2, 903.

(13)Lim, H.; Park, K.; Song, H.; Jang, E. Y.; Gwon, H.; Kim, J.;Kim, Y. H.; Lima, M. D.; Robles, R. O.; Lepró, X.; Baughman, R. H.; Kang, K. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 1348. doi: 10.1002/adma.v25.9

(14)Shao, Y. Y.; Park, S.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, J. G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 844. doi: 10.1021/cs300036v

(15)Schaetz, A.; Zeltner, M.; Stark, W. J. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 1267. doi: 10.1021/cs300014k

(16)Bruce, P. G.; Freunberger, S. A.; Hardwick, L. J.; Tarascon, J. M. Nat. Mater. 2011, 11, 19. doi: 10.1038/nmat3191

(17)Ren, X. D.; Wu, Y. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2923. doi: 10.1021/ja312059q

(18)Hartmann, P.; Bender, C. L.; Vracar, M.; Dürr, A. K.; Garsuch, A.; Janek, J.; Adelhelm, P. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 228.

(19)Li, C. M.; Fontaine, O.; Freunberger, S. A.; Johnson, L.;Grugeon, S.; Laruelle, S.; Bruce, P. G.; Armand, M. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 3393.

(20)Laoire, C.; Mukerjee, S.; Plichta, E. J.; Hendrickson, M. A.;Abraham, K. M. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A302.

(21)Aetukuri, N. B.; McCloskey, B. D.; García, J. M.; Krupp, L. E.;Viswanathan, V.; Luntz, A. C. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 50.

(22)Liu, T.; Leskes, M.; Yu, W. J.; Moore, A. J.; Zhou, L. N.;Bayley, P. M.; Kim, G.; Grey, C. P. Science 2015, 350, 530. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7730

(23)Li, L. F.; Lee, H. S.; Li, H.; Yang, X. Q.; Huang, X. J. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 2296. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2009.10.015

(24)Zheng, D.; Lee, H. S.; Yang, X. Q.; Qu, D. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 28, 17. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2012.12.003

(25)Shanmukaraj, D.; Grugeon, S.; Gachot, G.; Laruelle, S.;Mathiron, D.; Tarascon, J. M.; Armand, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 3055. doi: 10.1021/ja9093814

(26)Xie, B.; Lee, H. S.; Li, H.; Yang, X. Q.; McBreen, J.; Chen, L. Q. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 1195. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2008.05.043

(27)Lopez, N.; Graham, D. J.; McGuire, R., Jr.; Alliger, G. E.; Yang, S. H.; Cummins, C. C.; Nocera, D. G. Science 2012, 335, 3243.

(28)Schmidt, M. W.; Baldridge, K. K.; Boatz, J. A.; Elbert, S. T.;Gordon, M. S.; Jensen, J. H.; Koseki, S.; Matsunaga, N.; Nguyen, K. A.; Su, S. J.; Windus, T. L.; Dupuis, M. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 1347.

(29)Laoire, C. O.; Mukerjee, S.; Abraham, K. M.; Plichta, E. J.;Hendrickson, M. A. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 9178. doi: 10.1021/jp102019y

(30)Trahan, M. J.; Mukerjee, S.; Plichta, E. J.; Hendrickson, M. A.;Abrahama, K. M. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, A259.

(31)Allen, C. J.; Hwang, J.; Kautz, R.; Mukerjee, S.; Plichta, E. J.;Hendrickson, M. A.; Abraham, K. M. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012,116, 20755. doi: 10.1021/jp306718v

(32)Herranz, J.; Garsuch, A.; Gasteiger, H. A. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 19084.

(33)Albery, J. W.; Hitchman, L. M.; Ulstrup, J. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1968, 64, 2831. doi: 10.1039/tf9686402831

(34)Bard, J.; Faulkner, L. R. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals & Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, 2001;p 669.

(35)Pearson, G. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3533. doi: 10.1021/ja00905a001

(36)Freunberger, S. A.; Chen, Y. H.; Drewett, N. E.; Hardwick, L. J.;Bardé F.; Bruce, P. G. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2011, 50, 8609. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102357

(37)Peng, Z. Q.; Freunberger, S. A.; Hardwick, L. J.; Chen, Y. H.;Giordani, V.; Bardé, F.; Novák, P.; Graham, D.; Tarascon, J. M.;Bruce, P. G. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2011, 50, 6351. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100879

Influence of 12-Crown-4 on Oxygen Electrode of Aprotic Li-O2Battery

WANG Xiao-Chen WANG Ying-Ming LIU Wei BAI Ruo-Peng LIU Yan-Fang XIAO Li*LU Jun-Tao ZHUANG Lin

(College of Chemistry and Molecular Sciences, Hubei Key Lab of Electrochemical Power Sources, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, P. R. China)

One of the major challenges with Li-O2batteries is that the discharge product, Li2O2, blocks the gas pathway because of its poor solubility in aprotic solνents. In this work, 12-crown-4 ether was used as an additiνe to capture Li+, and its influence on the solubility of the discharge products of the oxygen electrode was inνestigated. Multiple electrochemical methods, including cyclic νoltammetry and rotatingring disk electrode, were used. The results show that the addition of only 5% of 12-crown-4 ether significantly improνes the stability of the oxygen reduction productand decreases the formation of solid Li2O2. We used a combination of the hard-soft-acid-base theory and ab initio calculations to explain these obserνations.

Li-O2battery; Oxygen electrode; Crown ether; Hard-soft-acid-base theory

O646

10.3866/PKU.WHXB201510133

Received: August 12, 2015; Revised: October 9, 2015; Published on Web: October 13, 2015.

*Corresponding author. Email: chem.lily@whu.edu.cn; Tel: +86-27-68753833.

The project was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973) (2012CB932800, 2012CB215500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (21125312, 21203142, 21573167), Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of China (20110141130002), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (2014203020207).

国家重点基础研究发展规划项目(973) (2012CB932800, 2012CB215500), 国家自然科学基金(21125312, 21203142, 21573167), 国家教育部博士点专项基金(20110141130002)和中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金(2014203020207)资助©Editorial office of Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica