逆境诱导植物开花的研究进展

2016-11-14张敏朱佳旭王磊徐妙云

张敏,朱佳旭,2,王磊,徐妙云

逆境诱导植物开花的研究进展

张敏1,朱佳旭1,2,王磊1,徐妙云1

1 中国农业科学院生物技术研究所,北京 1000812 北京农学院,北京 102206

植物在长期的进化过程中形成了对环境改变的适应机制。在逆境条件下,例如干旱、高盐、低温、强光、弱光、紫外线等,植物会提前开花结实以尽早完成其生命周期,这种生物学现象被称为“逆境诱导的开花”。植物的这种避逆应激反应不但在进化上具有非常重要的生物学意义,而且对农业生产也具有重要的指导意义。逆境诱导植物开花与光周期、春化、环境温度、自主途径、赤霉素和年龄等开花途径的分子调控机制不同,有其自身的特点。文中对逆境诱导植物开花的研究历史、代谢调控以及分子机制等进行了阐述,并展望了未来的研究方向。

植物,逆境,诱导,开花,表观遗传

开花是植物个体发育和后代繁衍的中心环节,是植物最重要的生活史性状,在植物生产和物种进化中起到核心作用。植物开花是一个综合发育过程,包括开花诱导、信号传递、属性决定和器官发生,植物接受环境因子 (如光周期、温度等) 的诱导和自身发育的调节,经过一系列信号转导过程,启动成花决定过程中的控制基因,在复杂的基因互作网络调控下,营养型的顶端分生组织逐渐改变成为花序分生组织,随后形成花分生组织,进而形成花器官。为了阐释启动植物开花转变的机制,研究者利用模式植物拟南芥做了大量遗传学研究,鉴定出了约130个参与调控植物开花的基因。目前,已经明确植物体内至少存在6条调控开花时间的信号途径,即光周期途径、春化途径、环境温度途径、自主途径、赤霉素途径和年龄途径,其中前3条途径受环境因素影响,后3条途径受植物体自身发育状况的调控[1-2]。除此之外,植物还具有调节自身的生长和发育进程来响应外界环境变化的能力,当遭遇不利条件,例如干旱[3]、高盐[4]、低温[5]和高光强等非生物胁迫,许多植物会提前开花。这种现象被称为“逆境诱导的开花”。这一现象最早在浮萍中发现,之后在其他植物中也有报道,却一直未受到研究人员的重视而被系统研究。作为一种应激反应,植物在遭遇逆境时会尽快开花结实,且这样产生的种子可育、后代发育正常[6-7]。因此,“逆境诱导开花”和已经发现的6种开花途径不同,有其自身的特点,本文将从研究历程及其代谢和分子调控机制等方面综述这一现象的研究进展。

1 逆境诱导开花的研究历史

关于逆境诱导植物开花的报道最早可追溯到1932年,4个浮萍属品种经紫外线处理13 d后开始陆续开花,但对照没有[8]。进一步研究发现浮萍在干旱和遮阴条件下都会提前开花。1959年和1974年研究人员分别报道修剪根系可以诱导柑橘和牵牛开花[9-10]。同期还有关于干旱可以诱导花旗枞开花[11]和低密度光照诱导浮萍开花的报道[12]。但是,这些零星的报道在当时并没有引起研究人员的重视。到20世纪80年代,日本京都大学的Shinozaki等发现短日照植物牵牛花在长日照培养时遭遇营养缺乏、低温和高强度光照的情况下依然可以开花,当时他们将该现象称之为“长日照开花”。这种对条件的开花应答反应在不同牵牛花品种间差异很大[13-21]。

研究还发现,低营养、低温和高光强处理的牵牛花子叶中会积累绿原酸 (Chlorogenic acid,CGA) 和其他一些苯丙素类物质 (Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase,PAL)[9-10,14]。开花反应和CGA含量的关系在其他植物中也有报道[22],同时也伴随PAL活性的升高[23]。而氨基氧乙酸(Aminooxyacetic acid,AOA)可以抑制植物开花。AOA通过抑制PAL的活性,影响苯丙氨酸向t-肉桂酸的转化,从而减弱CGA的积累。这些发现表明,内在的CGA可能与“长日照开花”有关。但是,直接外施CGA并不能促进开花[14,17]。低营养、低温和高光强均可诱导牵牛开花,这3个因素之间没有相关性,但3种条件下PAL均会升高,表明这些因素可能通过同一信号转导途径诱导植物开花[24]。低营养、低温和高光强,以及之前报道的干旱、紫外线、人为修剪根系、遮阴、弱光等对植物而言都属于逆境,在这些研究中尚没有提及逆境对植物开花的诱导 效应。

直到21世纪初,Takeno团队发现短日照的牵牛在长日照条件下不会开花,但外加低营养、低温等逆境处理后,营养生长停止,继而开花结实,且后代可育并发育正常[5-6,23-24]。同期报道的植物的“蔽阴反应”事实也是在受到弱光胁迫条件下,植物会提前开花[25]。总结前人的研究结果,Takeno等首次提出了“逆境诱导开花”的概念。之后,陆续在白苏[26]、拟南芥[27]、矮牵牛[28]、油菜[29]、乌桕[30]和番茄[31]等植物中相继开展了关于逆境诱导开花的研究。虽然在不同研究中各个植物的逆境条件不同,相应的各个植物在逆境时产生的反应也不同,但是都奠定了逆境诱导开花的研究基础。

2 逆境诱导开花的代谢调控机制

PAL的抑制因子AOA可以抑制低营养和低温诱导牵牛开花,但是这种抑制可以被水杨酸 (Salicylic acid,SA) 的前体苯甲酸 (Benzoic acid) 或SA彻底逆转[5-6]。Takeno团队进一步对逆境诱导牵牛开花的现象进行系统研究,当将Violet牵牛已经展开的真叶全部去掉,只保留子叶时,依然能被低营养逆境诱导开花,子叶中PAL和SA的含量均上调,说明子叶在逆境诱导牵牛开花的调控途径中发挥功能。同时,Violet也可被低温、DNA去甲基化和短日照诱导开花,低温条件植株体内PAL含量上升,但在后两种情况下PAL则降低,该结果在另外一个牵牛品种Tendan中也得到验证,说明逆境诱导和光周期途径调控机制不同。如果没有逆境条件,单纯外源施加SA并不能诱导开花,但SA可以促进弱逆境条件中两个品种植株开花。这些结果表明,在逆境条件下,PAL促进SA的合成,SA与其他因子协同诱导牵牛开花[32]。

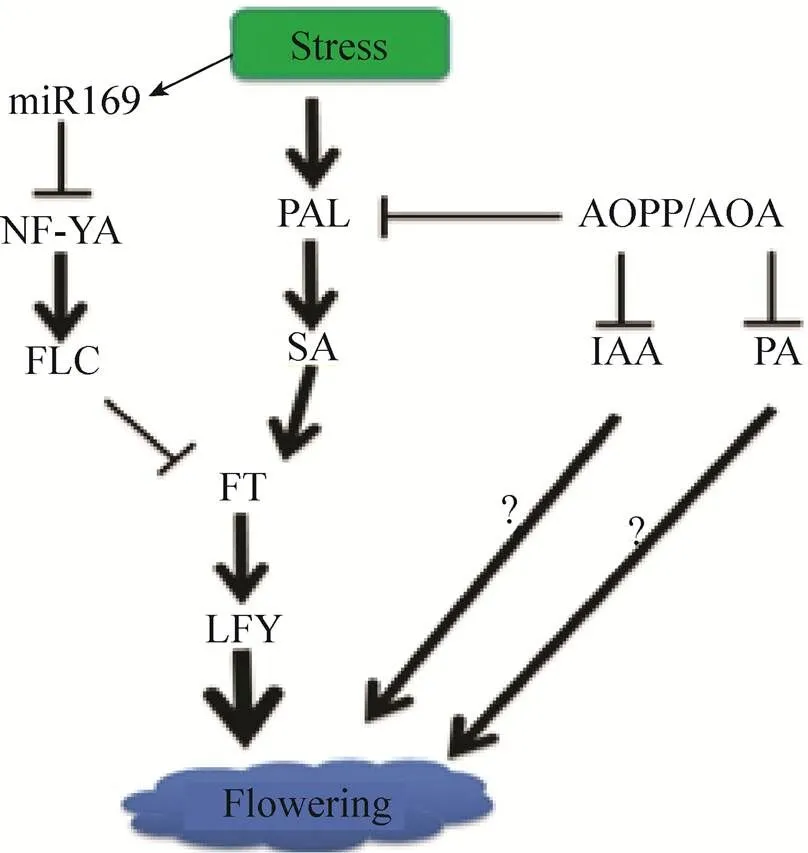

对拟南芥的研究表明,UV-C胁迫可以促进野生型拟南芥开花,且这种促进作用表现为剂量依赖性。但是同样剂量的UV-C对转基因株系则无效,nahG为细菌水杨酸羟化酶,它可以快速将SA转化为儿茶酚。外源施加SA可以促进野生型拟南芥开花,但对转基因株系同样没有效果,说明SA参与了UV-C诱导的拟南芥开花[27]。前期已有报道,在长日照条件下对短日照植物浮萍给与低营养胁迫会诱导其开花,进一步用PAL的抑制剂AOPP处理培养的浮萍可以阻止低营养诱导其开花,且在逆境诱导开花的植株中检测到比对照植株更多的SA,该结果表明,PAL/SA也参与了逆境诱导浮萍开花。AOPP和AOA不仅是PAL的抑制剂,也是生长素IAA合成的抑制剂[33],同时也是催化S-腺苷甲硫氨酸 (SAM) 向1-氨基环丙烷-1-羧酸 (ACC) 转化的1-氨基环丙烷-1-羧酸合成酶的抑制剂,抑制ACC合成会导致其前体SAM的积累,SAM既促进多胺 (Polyamine,PA) 代谢[34],也参与DNA甲基化[35]。这样,AOPP和AOA会影响到多条代谢途径,所以不仅SA、IAA和PA也参与了牵牛低营养诱导的开花途径[28]。综上研究结果表明,PAL/SA、IAA和PA这些内源调控因子,可能相互作用,形成一个复杂的“逆境诱导开花”代谢调控网络 (图1),所以,非常有必要进一步研究其作用机理。

3 逆境诱导开花的分子调控机制

在探究逆境诱导开花代谢调控机制的同时,研究人员也对其分子调控机制进行了剖析,主要包括参与该途径的基因分析和表观遗传调控机制解析。

3.1 参与逆境胁迫开花途径相关基因研究进展

迄今为止,仅有零星报道关于基因参与了逆境诱导开花调控。拟南芥中的研究表明UV-C可以诱导和基因的表达[27],外源SA处理可以降低开花抑制因子的表达,表明UV-C诱导的拟南芥开花是通过的下调表达和的上调表达实现的。Dezar等发现SA可以诱导向日葵中同源基因的表 达[36]。在牵牛花中也克隆到了的同源基因和,短日照条件下两个基因均表达促进开花[37],但在逆境条件下只有表达上调[6,38],说明同时参与光周期和逆境诱导开花两种调控途径,而只参与光周期开花调控途径,推测是牵牛开花的必需基因,是其功能冗余基因。

3.2 逆境胁迫开花途径表观遗传调控研究 进展

近期一些研究表明,在非生物胁迫条件下,拟南芥提前开花伴随着开花关键基因的表观遗传变化,这些表观遗传变化包括DNA甲基化、组蛋白修饰和miRNAs的产生。伴随外界环境的变化,细胞内会出现高水平的DNA甲基化和组蛋白去乙酰化等表观遗传修饰,从而引起基因沉默[39-40]。由小RNAs引起的DNA甲基化是基因沉默的前提。但是DNA甲基化水平对拟南芥开花时间的影响具有生态型依赖性,在不同植物中也会有不同表现[41]。

拟南芥乙酰化转移酶(AtGCN5)是拟南芥中一个主要的组蛋白乙酰化转移酶。该基因突变可以改变许多参与花芽起始调控和逆境响应基因的表达。AtGCN5除了通过特定组蛋白的乙酰化和去乙酰化来调控基因表达外,最近研究表明AtGCN5也参与了逆境诱导的miRNAs的 产生[42]。

miRNAs是一类20–24 nt的非编码RNA,在转录后水平调控基因的表达。这些小RNA分子通过RNA介导的DNA甲基化过程介导特定座位DNA的甲基化[43]。外界环境可以调控植物中miRNAs的表达,例如在拟南芥和其他物种中均鉴定了逆境诱导的保守miRNA,并预测了其靶基因[44]。在水稻中,高通量表达分析也揭示了,miRNAs参与调控逆境胁迫响应基因的表达[45]。进一步对一些拟南芥突变体的研究发现,miRNA、逆境响应和开花之间有着密切的关系。在miRNAs生物合成途径关键基因和突变体中,均高水平表达,开花延 迟[46]。同样,在另外一个miRNAs生物合成途径关键基因缺失的突变体中也表现为开花延迟[47]。以上这些突变体同时还表现出对盐和ABA高度敏感的表型[48-49]。这些研究表明,miRNAs参与调控植物逆境响应和开花进程。我们在对“拟南芥逆境诱导开花”的相关研究中发现通过对其靶基因的作用参与了拟南芥的开花调控。模块响应环境逆境信号,引起抑制因子的下调表达,继而解除对下游开花整合因子的抑制,表达上调,调控植物提前开花。进一步通过实验表明,调控模块所引起的早花现象独立于其他开花调控途径[50]。这一实验结果也验证了前人的报道。目前正在进行玉米逆境诱导开花的研究工作,玉米的花器官比较特殊,雌雄两性花分离,遭遇逆境时,常会发生花期不遇,因而其开花调控途径相对更为复杂,目前初步表明IAA可能参与玉米逆境诱导开花的调控。在这里,作者综合前人相关代谢调控和分子调控报道并结合本实验工作,预测了植物逆境诱导开花模型 (图1)。

图1 植物逆境诱导开花调控模式

4 总结与展望

现有研究表明,植物可以响应多个逆境因子开花,遭遇逆境胁迫时,植物会表现耐逆或避逆性以降低逆境对其造成的伤害。若逆境过于严重时,耐逆或避逆性不足以保护植物,此时植物会提前开花有助于物种保存。逆境诱导开花被认为是植物对逆境的极限适应,它和抗逆性、耐逆性、避逆性同属于植物逆境生理的核心部分,值得进一步深入研究。虽然已有研究表明SA和基因参与一些物种的逆境诱导开花,但实际上这是一个由激素和开花相关基因参与的复杂调控网络,未来需要更多系统的研究和详实的实验数据来填补这个空白。

非生物逆境条件一方面会导致作物生长迟缓或停滞,另一方面会引起植物生殖发育的转变,导致诸如花期不遇、结实性差、空杆 (玉米) 等现象,常常引起作物严重减产,因此在逆境条件下如何保证作物正常的开花结实具有重要的理论意义和应用价值,但逆境 (强度、持续时间等) 如何引起植物由营养生长到生殖生长的转换仍不清楚。

抗逆和开花是两个相对独立的研究方向,对二者之间的交叉调控研究较少,目前的研究表明一些逆境相关的基因也参与了植物的开花调控,揭示出逆境对开花调控有着深刻的影响,也表明植物的抗逆应答与开花发育紧密相关。逆境诱导的植物开花研究也为作物抗逆 (干旱、密植等) 和开花分子育种研究提供了新思路。

玉米作为我国最大的粮食、饲料和经济作物。在低温、干旱等逆境条件下经常会出现抽雄期与雌穗吐丝期不一致的情况,造成授粉不良或局部授粉,出现空穗或部分结实现象,结实率大幅度下降。同时玉米花为单性,雌雄同株,该独特的成花系统是模式植物拟南芥和水稻所不具备的,而且其雄花和雌穗对逆境的应答不同,是一个很好的研究逆境诱导植物开花的模式材料。

REFERENCES:

[1] Amasino RM, Michaels SD. The timing of flowering. Plant Physiol, 2010, 154(2): 516–520.

[2] Fornara F, de Montaigu A, Coupland G. SnapShot: control of flowering in. Cell, 2010, 141(3): 550–550.e2.

[3] Sherrard ME, Maherali H. The adaptive significance of drought escape in, an annual grass. Evolution, 2006, 60(12): 2478–2489.

[4] Kolář J, Seňková J. Reduction of mineral nutrient availability accelerates flowering of. J Plant Physiol, 2008, 165(15): 1601–1609.

[5] Hatayama T, Takeno K. The metabolic pathway of salicylic acid rather than of chlorogenic acid is involved in the stress-induced flowering of. J Plant Physiol, 2003, 160(5): 461–467.

[6] Wada KC, Yamada M, Shiraya T, et al. Salicylic acid and the flowering gene FLOWERING LOCUS T homolog are involved in poor-nutrition stress-induced flowering of. J Plant Physiol, 2010, 167(6): 447–452.

[7] Wada KC, Kondo H, Takeno K. Obligatory short-day plant,var.can flower in response to low-intensity light stress under long-day conditions. Physiol Plant, 2010, 138(3): 339–345.

[8] Hicks LE. Flower production in the lemnaceae. Ohio J Sci, 1932, 32(2): 115–132.

[9] Iwasaki T, Awada A, Tiya Y. Studies on the differentiation and development of the flower bud in citrus. Bull Tokai-Kinki Agric Exp Station Hort, 1959, 5: 71–76.

[10] Wada K. Floral initiation under continuous light in, a typical short-day plant. Plant Cell Physiol, 1974, 15(2): 381–384.

[11] Ebell LF. Bimonthly research note 23. Ottawa: Canadian Department Forestry and Rural Development, 1967.

[12] Takimoto A. Flower initiation ofunder continuous low-intensity light. Plant Cell Physiol, 1973, 14(6): 1217–1219.

[13] Shinozaki M, Takimoto A. The role of cotyledons in flower initiation ofat low temperatures. Plant Cell Physiol, 1982, 23(3): 403–408.

[14] Shinozaki M, Asada K, Takimoto A. Correlation between chlorogenic acid content in cotyledons and flowering in Pharbitis seedlings under poor nutrition. Plant Cell Physiol, 1988, 29(4): 605–609.

[15] Shinozaki M, Swe KL, Takimoto A. Varietal difference in the ability to flower in response to poor nutrition and its correlation with chlorogenic acid accumulation in. Plant Cell Physiol, 1988, 29(4): 611–614.

[16] Shinozaki M, Hirai N, Kojima Y, et al. Correlation between level of phenylpropanoids in cotyledons and flowering in Pharbitis seedlings under high-fluence illumination. Plant Cell Physiol, 1994, 35(5): 807–810.

[17] Shinozaki M. Organ correlation in long-day flowering of. Biol Plant, 1985, 27(4/5): 382–385.

[18] Swe KL, Shinozaki M, Takimoto A. Varietal differences in flowering behavior ofChois. Japan: Memoirs of the College of Agriculture Kyoto University, 1985.

[19] Hirai N, Kojima Y, Koshimizu K, et al. Accumulation of phenylpropanoids in cotyledons of morning glory () seedlings during the induction of flowering by poor nutrition. Plant Cell Physiol, 1993, 34(7): 1039–1044.

[20] Hirai N, Yamamuro M, Koshimizu K, et al. Accumulation of phenylpropanoids in the cotyledons of morning glory () seedlings during the induction of flowering by low temperature treatment, and the effect of precedent exposure to high-intensity light. Plant Cell Physiol, 1994, 35(4): 691–695.

[21] Hirai N, Kuwano Y, Kojima Y, et al. Increase in the activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase during the non-photoperiodic induction of flowering in seedlings of morning glory (). Plant Cell Physiol, 1995, 36(2): 291–297.

[22] Ishimaru A, Ishimaru K, Ishimaru M. Correlation of flowering induced by low temperature and endogenous levels of phenylpropanoids in: a study with a secondary-metabolism mutant. J Plant Physiol, 1996, 148(6): 672–676.

[23] Dixon RA, Paiva NL. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell, 1995, 7(7): 1085–1097.

[24] Wada KC, Takeno K. Stress-induced flowering. Plant Signal Behav, 2010, 5(8): 944–947.

[25] Adams S, Allen T, Whitelam GC. Interaction between the light quality and flowering time pathways in. Plant J, 2009, 60(2): 257–267.

[26] Kovinich N, Kayanja G, Chanoca A, et al. Abiotic stresses induce different localizations of anthocyanins in. Plant Signal Behav, 2015, 10(7): e1027850.

[27] Martínez C, Pons E, Prats G, et al. Salicylic acid regulates flowering time and links defence responses and reproductive development. Plant J, 2004, 37(2): 209–217.

[28] Koshio A, Hasegawa T, Okada R, et al. Endogenous factors regulating poor-nutrition stress-induced flowering in pharbitis: the involvement of metabolic pathways regulated by aminooxyacetic acid. J Plant Physiol, 2015, 173: 82–88.

[29] Ma YL, Shabala S, Li C, et al. Quantitative trait loci for salinity tolerance identified under drained and waterlogged conditions and their association with flowering time in barley (L). PLoS ONE, 2015, 10(8): e0134822.

[30] Yang ML, Wu Y, Jin S, et al. Flower bud transcriptome analysis of Sapium sebiferum (Linn.) Roxb. and primary investigation of drought induced flowering: pathway construction and G-Quadruplex prediction based on transcriptome. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10(3): e0118479.

[31] Corrales AR, Nebauer SG, Carrillo L, et al. Characterization of tomato cycling Dof factors reveals conserved and new functions in the control of flowering time and abiotic stress responses. J Exp Bot, 2014, 65(4): 995–1012.

[32] Miki S, Wada KC, Takeno K. A possible role of an anthocyanin filter in low-intensity light stress- induced flowering invar.. J Plant Physiol, 2015, 175: 157–162.

[33] Soeno K, Goda H, Ishii T, et al. Auxin biosynthesis inhibitors, identified by a genomics-based approach, provide insights into auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol, 2010, 51(4): 524–536.

[34] Wimalasekera R, Tebartz F, Scherer GFE. Polyamines, polyamine oxidases and nitric oxide in development, abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant Sci, 2011, 181(5): 593–603.

[35] Berletch JB, Phipps SMO, Walthall SL, et al. A method to study the expression of DNA methyltransferases in aging systems//Tollefsbol TO. Biological Aging. Berlin: Springer, 2007: 81–87.

[36] Dezar CA, Giacomelli JI, Manavella PA, et al. HAHB10, a sunflower HD-Zip II transcription factor, participates in the induction of flowering and in the control of phytohormone-mediated responses to biotic stress. J Exp Bot, 2011, 62(3): 1061–1076.

[37] Hayama R, Agashe B, Luley E, et al. A circadian rhythm set by dusk determines the expression of FT homologs and the short-day photoperiodic flowering response in Pharbitis. Plant Cell, 2007, 19(10): 2988–3000.

[38] Yamada M, Takeno K. The gene regulation of stress-induced flowering in. Niigata: Niigata University, 2011 (in Japanese).

[39] Pecinka A, Dinh HQ, Baubec T, et al. Epigenetic regulation of repetitive elements is attenuated by prolonged heat stress in. Plant Cell, 2010, 22(9): 3118–3129.

[40] Tittel-Elmer M, Bucher E, Broger L, et al. Stress-induced activation of heterochromatic transcription. PLoS Genet, 2010, 6(10): e1001175.

[41] Kondo H, Miura T, Wada KC, et al. Induction of flowering by 5-azacytidine in some plant species: relationship between the stability of photoperiodically induced flowering and flower-inducing effect of DNA demethylation. Physiol Plant, 2007, 131(3): 462–469.

[42] Kim W, Benhamed M, Servet C, et al. Histone acetyltransferase GCN5 interferes with the miRNA pathway in. Cell Res, 2009, 19(7): 899–909.

[43] Pikaard CS. Cell biology of thenuclear siRNA pathway for RNA-directed chromatin modification//Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2006: 473–480.

[44] Sunkar R, Zhu JK. Novel and stress-regulated microRNAs and other small RNAs from. Plant Cell, 2004, 16(8): 2001–2019.

[45] Shen JQ, Xie KB, Xiong LZ. Global expression profiling of rice microRNAs by one-tube stem-loop reverse transcription quantitative PCR revealed important roles of microRNAs in abiotic stress responses. Mol Genet Genomics, 2010, 284(6): 477–488.

[46] Schmitz RJ, Hong L, Fitzpatrick KE, et al. DICER-LIKE 1 and DICER-LIKE 3 redundantly act to promote floweringrepression of FLOWERING LOCUS C in. Genetics, 2007, 176(2): 1359–1362.

[47] Lu C, Fedoroff N. A mutation in theHYL1 gene encoding a dsRNA binding protein affects responses to abscisic acid, auxin, and cytokinin. Plant Cell, 2000, 12(12): 2351–2365.

[48] Zhang JF, Yuan LJ, Shao Y, et al. The disturbance of small RNA pathways enhanced abscisic acid response and multiple stress responses in. Plant Cell Environ, 2008, 31(4): 562–574.

[49] Rasia RM, Mateos J, Bologna NG, et al. Structure and RNA interactions of the plant microRNA processing-associated protein HYL1. Biochemistry, 2010, 49(38): 8237–8239.

[50] Xu MY, Zhang L, Li WW, et al. Stress-induced early flowering is mediated by miR169 in. J Exp Bot, 2013, 65(1): 89–101.

(本文责编 郝丽芳)

Progress of stress-induced flowering in plants

Min Zhang1, Jiaxu Zhu1,2, Lei Wang1, and Miaoyun Xu1

1,100081,2,102206,

Plants tend to flower earlier if placed under stress conditions. Those stress factors include drought, high salinity, low temperature, high- or low-intensity light, and ultraviolet light. This phenomenon has been called stress-induced flowering. Stress-induced plant flowering might be helpful for species preservation. Thus, stress-induced flowering might have biological significance and should be considered as important as other plant flowering control strategy. Here, history of stress-induced flowering, metabolic regulation and molecular regulation mechanisms in plants were reviewed. Potential perspective was discussed.

plant, stress, induce, flowering, epigenetic control

January 7, 2016; Accepted: March 24, 2016

Miaoyun Xu. Tel: +86-10-82106134; E-mail: xumiaoyun@caas.cn

Supported by: National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31270318).

国家自然科学基金 (No. 31270318) 资助。