肉类食品中产气荚膜梭菌及其控制研究进展

2016-07-22贾珊珊李沛军陈从贵

贾珊珊++李沛军++陈从贵

摘 要:产气荚膜梭菌广泛存在于自然界,且可以形成芽孢,是导致肉类食物中毒和气性坏疽等的主要病原菌。本文综述了肉类食品中产气荚膜梭菌的污染情况、生长影响因素以及控制其生长的方法;指明了利用食用安全的天然物质,研发高效抑制产气荚膜梭菌生长的技术与方法,对保障肉制品安全和促进肉类工业健康发展的现实意义,旨在为人们选择适合肉类食品中抑制产气荚膜梭菌生长的途径提供参考。

关键词:产气荚膜梭菌;肉类食品;污染情况;控制研究

产气荚膜梭菌(Clostridium perfringens,

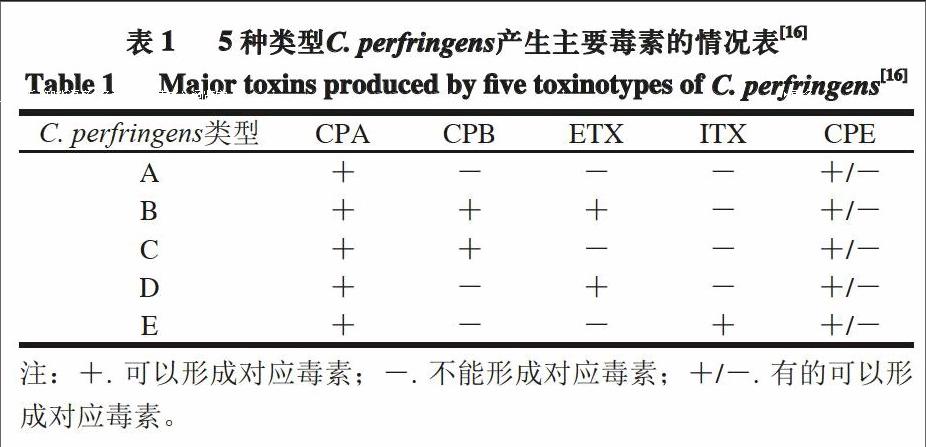

C. perfringens)是一种属于梭菌属的革兰氏阳性菌,具有荚膜,可产生芽孢,不具有运动性。C. perfringens是引起人畜共患病的主要病原菌之一,该菌的致病因子是其所产生的外毒素[1]。目前,已发现C. perfringens产生的外毒素多达17 种[2],并以α型(CPA)、β型(CPB)、ε型(ETX)和ι型(ITX)4 种毒素最为常见;C. perfringens还会产生其他多种毒素或者潜在的致毒因子,如肠毒素(CPE)[3]。根据所产毒素的不同,C. perfringens可分为5 种类型,它们与5 种主要毒素的对应关系见表1。5种C. perfringens均会导致特定的动物患病,其中A型和C型C. perfringens可引起人患病,例如,肠毒素引起的食物中毒、水样腹泻以及婴儿的突发性死亡,α型毒素引起的气性坏疽及β型毒素引起的人坏死性肠炎[4]。

在美国和一些发展中国家,由A型C. perfringens菌引起的食物中毒是最常见报道的食物中毒之一,目前在美国排名第2位,每年可导致食物中毒约100 万例[5-6]。

C. perfringens引起众多食物中毒事例的原因主要有:1)它广泛存在于自然界,包括土壤、人以及动物的肠道中[7];

2)它能在适宜的环境下快速生长,代时甚至小于

10 min[4,8];3)它可以产生多种毒素,导致人或动物患病,尤其是A型C. perfringens[9]。

不仅如此,C. perfringens对生长环境的要求较低,也是容易在食品中爆发的重要原因。其最适生长pH值为6~7[10],但在pH 5~9范围仍可生长;它可在15~50 ℃快速生长[11],在15 ℃以下亦可缓慢生长,甚至可在6 ℃条件下生长[12];其生长的最低水分活度值为0.95。

C. perfringens芽孢能够耐高温,在煮沸15 min或更长的时间仍可存活[13],并可在10~54 ℃温度内快速萌发和二次生长[14]。此外,C. perfringens还对肉类食品中各种防腐方法具有较高的抵抗能力[13-15]。

1 肉类食品中C. perfringens的污染情况

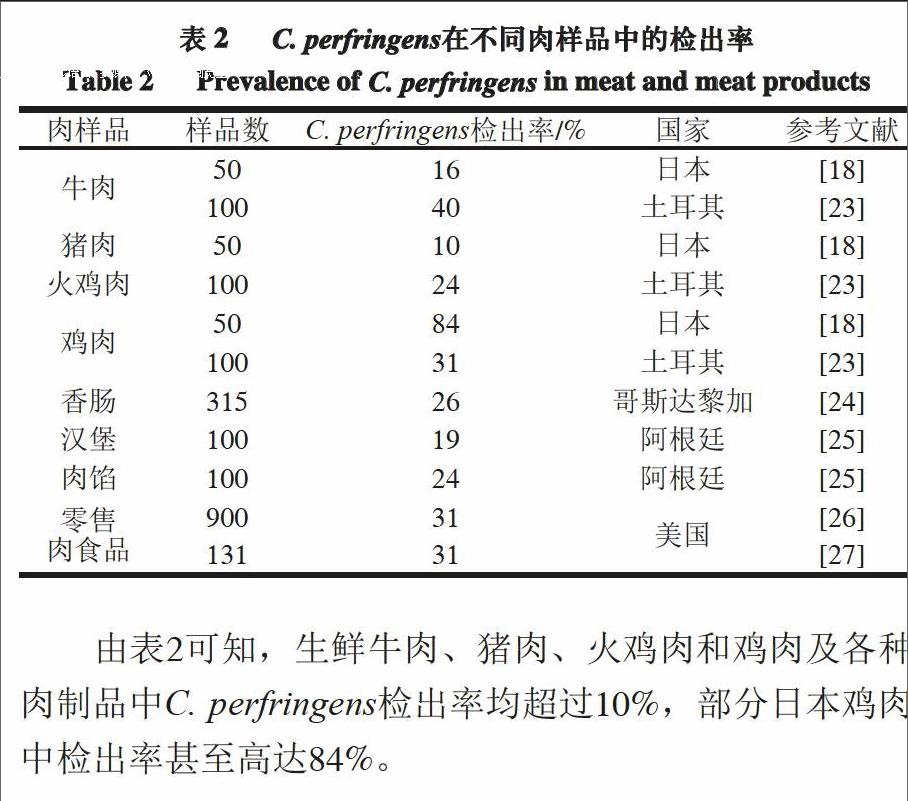

由C. perfringens导致的食物中毒多与肉和禽肉制品相关[17-18]。调查美国1998—2010年由C. perfringens引起食物中毒的结果显示,肉类食品占食物总量的92%,其中牛肉制品占46%,禽肉制品占30%,猪肉制品占16%[19]。不仅肉制品容易被C. perfringens污染,原料肉由于富含蛋白质也容易成为C. perfringens滋生的土壤[18,20]。富含蛋白质的动物在屠宰过程中会被来自其肠道或粪便中的C. perfringens污染[21];而原料食品和加工食品中

C. perfringens的污染率也分别高达30%和80%[22]。表2列出了近年来C. perfringens在部分国家肉样品中的检出率。

由表2可知,生鲜牛肉、猪肉、火鸡肉和鸡肉及各种肉制品中C. perfringens检出率均超过10%,部分日本鸡肉中检出率甚至高达84%。

2 肉类食品中C. perfringens生长的影响因素

Bennett等[28]对1998—2008年在美国由

C. perfringens、金黄色葡萄球菌和蜡样芽孢杆菌引起食物中毒事件的数据进行了统计分析。结果表明,无论是哪种致病菌,最常见引起食物中毒的错误操作发生于食物加工和准备的过程中,占所有因素的93%。比如,肉制品煮制后经过不适当冷却工艺(44%);将肉制品放置于不合适贮藏温度下(22%)。Li[22]和Mcclure[29]等也指出,肉制品煮制后不适当冷却工艺和不合适的贮藏温度是C. perfringens暴发的最常见原因。

2.1 不适当冷却工艺

科学合理的冷却工艺,应能最大程度地抑制致病菌芽孢的萌发及二次生长。热加工可能无法完全致死

C. perfringens的芽孢,还可能诱导芽孢萌发,使其在较高温度下快速萌发并生长。C. perfringens是肉制品降温过程是否安全的指示菌。有研究表明,向煮熟牛肉糜中接种3 种可形成芽孢的致病菌(枯草芽孢杆菌、C. perfringens和肉毒梭状芽孢杆菌)时,经历长达18 h的降温过程后,C. perfringens数量增加了4~5(lg(CFU/g)),而其他2 种致病菌均无显著生长[30]。美国对煮制肉制品的冷却工艺进行了严格规定。对于非熏制的煮制肉及禽肉制品的冷却过程,美国农业部食品安全及检验局明确规定:从54.4 ℃降至26.7 ℃不得超过1.5 h,从26.7 ℃降至4.4 ℃不超过5 h[31]。

肉和禽肉制品的不合适降温是导致C. perfringens生长进而引起食物中毒事件的重要因素。Valenzuela-Martinez等[32]将数量约为2~2.5 (lg(CFU/g))的C. perfringens芽孢接种到真空包装猪肉样品中,75 ℃水浴加热20 min诱导芽孢萌发,随后将样品分别于12、15、18、21 h内从54.4 ℃降至7.2 ℃,结果发现,C. perfringens的数量分别增至6.08、7.25、8.21、8.45 (lg(CFU/g))。Xiao等[33]的研究中也得到了相似的结果,在9、12、15、18、21 h内使样品从54.4 ℃降至4 ℃,结果发现,样品中

C. perfringens芽孢的量从初始接种的2.0~2.5(lg(CFU/g))分别增加了4.50、5.78、7.05、7.88、8.19(lg(CFU/g))。

2.2 不合适的贮藏温度

除了不适当的冷却工艺,肉制品在贮藏过程中发生温度波动或贮藏温度不合适亦会引起C. perfringens生长繁殖,对食品安全造成威胁。Juneja等[34]将15 株C. perfringens接种到真空包装牛肉中,放置于12 ℃温度下贮藏,分别测定0、1、4、7 d样品中C. perfringens的数量。结果显示,无论哪一种C. perfringens,样品中C. perfringens的数量均随贮藏天数的增加而急剧增长。Nieto-Lozano等[35]发现,真空包装的煮制火鸡样品在贮藏过程中,从4 ℃移至28 ℃的环境温度中,贮藏12 h后,样品中C. perfringens的量从2.0~2.5(lg(CFU/g))增至6.0(lg(CFU/g))。Mikelsaar等[36]发现将接种

C. perfringens的法兰克福香肠分别贮藏于10 ℃温度下60 d和15 ℃温度下30 d,结果发现C. perfringens的量从约为4.0 (lg(CFU/g))分别增加至5.7 (lg(CFU/g))和6.3(lg(CFU/g))左右。

3 肉类食品中C. perfringens的控制

3.1 原料肉源头控制C. perfringens的方法

3.1.1 益生菌

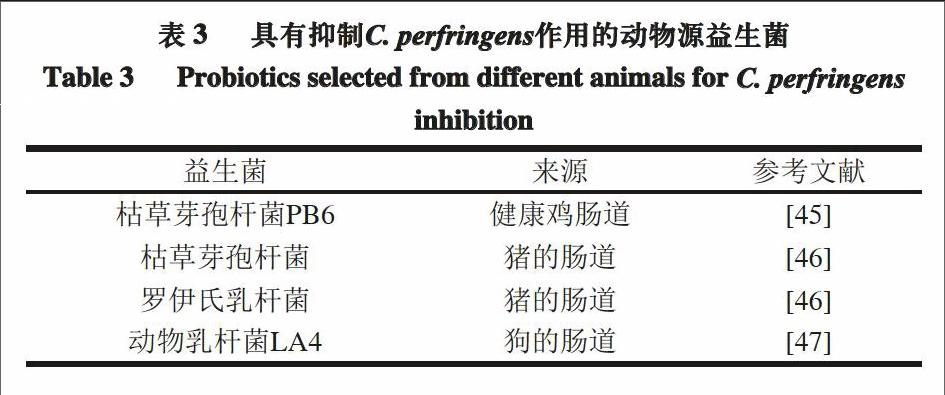

益生菌是一类对宿主有益的活性微生物的总称,通过口服等方式定植于宿主肠道、生殖系统内,能够抑制对人体有害微生物的生长,进而对宿主发挥有益作用[36]。乳杆菌、双歧杆菌和枯草芽孢杆菌均可作为益生菌,用于增强人体胃肠道中有益微生物的生长[37-38]。但到目前为止,人们对益生菌作用机制的研究还不充分,主要认为:益生菌通过与有害微生物竞争营养、降低胃肠道pH值以及产生某些特定的抑菌物质等方式,来抑制有害微生物的生长[39]。

有研究证实,乳杆菌和双歧杆菌能够减少

C. perfringens的数量。Kim等[40]从健康猪胃肠道中分离出5 株乳杆菌和2 株双歧杆菌,它们均可在体外模拟胃肠道环境下生长,其中,噬淀粉乳杆菌S6对C. perfringens的抑制作用要比金霉素和土霉素等抗生素更有效。Rinkinen等[41]的体外实验结果显示,乳杆菌可通过降低黏附能力来抑制C. perfringens的生长。

阳艳林等[42]从健康鸡的胃肠道中分离得到的一株枯草芽孢杆菌,可体外抑制C. perfringens ATCC 13124,并通过质谱分析发现,抑菌物质的相对分子质量约为960~980,且化学性质稳定。有公司以枯草芽孢杆菌PB6作为主要成分,生产出微生物制剂克洛生,并通过体外和体内实验,证明了它对抑制C. perfringens生长的有效性[43-44]。

表3列出了可以抑制动物体内C. perfringens的益生菌。

3.1.2 益生元

益生元(prebiotics)作为一类不易被人体消化吸收的食品成分,可选择性地刺激一种或几种肠道细菌的生长和活性,而对寄主产生有益的影响[48]。许多体外实验以及哺乳动物的体内实验证实,益生元对C. perfringens具有抑制作用。例如,与未添加的对照组相比,添加于动物饮食中的果寡糖,可以显著降低肠道中C. perfringens的数量[49];喂食添加有天然益生元糖类物质的动物,其体内C. perfringens的数量显著少于对照组[50-53]。也有研究证实,乳糖可用来抑制非哺乳动物鸡肠道内C. perfringens的数量,显示乳糖可能是一种适用于禽类的益生元物质[54]。

3.2 肉类食品中抑制C. perfringens生长的方法

3.2.1 有机酸及有机酸盐

在新型的食品抑菌剂中,有机酸以及有机酸盐被认为是较好的选择,因其具有较宽的抑菌谱,无毒、稳定,并具有对食品的颜色和风味无副作用等优点[55]。乳酸钠、乳酸钾、二乙酸钠等有机酸盐,已被广泛用于肉制品和禽肉制品,以抑制单核李斯特菌和其他腐败菌,增强食品的微生物安全[56-57]。有机酸的抑菌机理可能是:有机酸能够穿过细胞膜,使细胞内的pH值降低,导致带电离子的释放,并使质子不能穿过细胞膜,阻碍了代谢活动从而抑制细胞的生长[58]。目前被研究用来抑制

C. perfringens的有机酸盐主要有:乳酸钙、乳酸钾、乳酸钠、柠檬酸钠、山梨酸和苯甲酸、磷酸酸盐等[9, 31, 59-60]。

Saeed等[59]利用柠檬酸钠缓冲溶液及其与二乙酸钠的混合液,分别添加于烤牛肉中,结果发现:接种了

2.5(lg(CFU/g))C. perfringens的样品,在18 h内从54.4℃降至7.2 ℃时,烤牛肉对照组中C. perfringens的数量增加了3.70(lg(CFU/g));而添加了柠檬酸钠缓冲液及其混合液的样品中,C. perfringens的数量却减少了2.47(lg(CFU/g))。可见,柠檬酸钠缓冲液及其与二乙酸钠的混合物能够显著降低C. perfringens萌发和二次生长的潜在危险。

Valenzuela-Martinez等[32]观察了乳酸钙、乳酸钾和乳酸钠对猪肉降温过程中C. perfringens芽孢萌发和二次生长的影响情况,结果显示,猪肉制品中添加2.0%的乳酸钙或者3.0%的乳酸钾或乳酸钠,在54.4 ℃至7.2 ℃、长达21 h的降温过程中,可使产品中C. perfringens的增长量保持在可接受范围内;而对照组中C. perfringens却增长了6.30(lg(CFU/g))。

3.2.2 细菌素

细菌素通常被认为是由细菌生成的多肽类物质,能够抑制或杀死近源性和其他微生物[61]。有研究证实,罗伊氏菌素[62]、乳酸链球菌素[62-64]、乳酸片球菌素[35]、戊糖片球菌素[65]、乳酸乳球菌素[66]、粪肠球菌素[67]和芽孢杆菌素[68-69]等细菌素,均可体外抑制C. perfringens。片球菌素也能有效抑制单核李斯特菌、金黄色葡萄球菌、

C. perfringens等腐败菌和致病菌[70-71]。

但是在体内实验中,细菌素对C. perfringens的抑制作用非常有限[72]。细菌素可能被食品中内源性蛋白酶降解,或者被肉和脂肪颗粒吸收[73],由此影响了细菌素对体内C. perfringens的抑制效果。细菌素对体内

C. perfringens的抑制作用值得进一步研究。

3.2.3 壳聚糖

壳聚糖是由自然界几丁质脱乙酰作用得到的聚合物,食用安全,已广泛应用于食品领域。壳聚糖类似于米糠、麦麸等膳食纤维,不能被人体吸收,可增加肠道中有益微生物的数量,并减少C. perfringens等致病菌的数量。Juneja等[74]将壳聚糖添加到培养基以及仓鼠的食物中,通过体内和体外实验,观察壳聚糖对C. perfringens生长的影响,结果发现,壳聚糖可以显著抑制C. perfringens的体外生长,但对其体内生长量却无显著影响。

Aziz等[75]研究发现,即使牛肉和鸡肉经历了不合适的降温过程,壳聚糖也能有效抑制产品中C. perfringens芽孢的萌发和二次生长。Santos等[76]在体外实验中还发现,壳聚糖能有效抑制C. perfringens、金黄色葡萄球菌以及大肠杆菌等革兰氏阳性致病菌。

3.2.4 植物提取物和香精油

有体外实验结果表明,植物提取物和植物香精油可以抑制C. perfringens的生长[77-78],其中包括绿茶提取物[79]。植物提取物和香精油的抑菌效果与很多因素有关,除了与植物类型、生长地理位置以及生长环境相关外[21],还与提取方式、培养基种类、pH值以及培养温度有关[80]。

绿茶提取物具有抑制C. perfringens芽孢萌发及二次生长的作用。有学者将不同浓度的绿茶提取物,添加于C. perfringens芽孢接种量约3(lg(CFU/g))的牛肉、鸡肉和猪肉中,在煮制样品经历12、15、18、21 h从54.4℃降至7.2 ℃后,实验观察样品中C. perfringens的变化情况,结果显示:添加2%的绿茶提取物,3 种肉制品中

C. perfringens的数量均显著低于对照组;且提取物浓度不同,抑菌效果也不同[81]。

Demirci等[81]利用土耳其唇形科糙苏属植物中提取的香精油,通过体外抑制食源性致病菌实验,发现所提精油可以有效抑制C. perfringens、单核李斯特菌、蜡样芽孢杆菌和大肠杆菌O157:H7等致病菌的生长。Sebranek等[82]将冬季香薄荷精油添加到接种了C. perfringens A型菌株的意大利香肠中,在25 ℃贮藏30 d,观察香肠中

C. perfringens在贮藏过程的数量变化,结果表明,该精油可以显著抑制C. perfringens的生长,且在贮藏结束后,样品中C. perfringens的数量仅为2.80 (lg(CFU/g))。

4 结 语

C. perfringens在环境中分布广泛,很容易污染富含蛋白的肉类食品,对肉食品安全造成较大潜在威胁。现已研究证实,有机酸及有机酸盐、细菌素、壳聚糖和植物提取物等天然物质,可以有效抑制C. perfringens的生长,但其实际应用还很有限。随着人们对绿色食品和食品安全的日益重视,利用食用安全的天然成分,开展其对

C. perfringens的抑制作用研究,将会成为热点。而对于易受C. perfringens污染的肉及肉制品,研究与开发高效的抑制方法,并应用于实际生产,对保障肉制品安全和促进肉类工业健康发展,更具有重要的现实意义。

参考文献:

[1] 陈小云, 关孚时, 张存帅, 等. 产气荚膜梭菌主要外毒素最新研究进展[J]. 中国兽药杂志, 2005, 39(6): 29-33. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-1280.2005.06.009.

[2] MCCLANE B A, UZAL F A, MIYAKAWA M E F, et al. The enterotoxic Clostridia[J]. Prokaryotes, 2006, 4: 698-752. DOI: 10.1007/springerreference_3743.

[3] UZAL F A, FREEDMAN J C, SHRESTHA A, et al. Towards an understanding of the role of Clostridium perfringens toxins in human and animal disease[J]. Future Microbiology, 2014, 9(3): 361-377. DOI: 10.2217/fmb.13.168.

[4] LINDSTR M M, HEIKINHEIMO A, LAHTI P, et al. Novel insights into the epidemiology of Clostridium perfringens type A food poisoning[J]. Food Microbiology, 2011, 28(2): 192-198. DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.03.020.

[5] SCALLAN E, HOEKSTRA R M, ANGULO F J, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States: major pathogens[J]. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2011, 17(1): 7-15. DOI: 10.3201/eid1701.p11101.

[6] HOFFMANN S, BATZ M B, MORRJS J J G. Annual cost of illness and quality-adjusted life year losses in the United States due to 14 foodborne pathogens[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2012, 75(7): 1292-1302. DOI: 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-11-417.

[7] STEELE F, WRIGHT K. Cooling rate effect on outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens in cooked, ready-to-eat turkey breast roasts[J]. Poultry Science, 2001, 80(6): 813-816. DOI: 10.1093/ps/80.6.813.

[8] LABBE R G, HUANG T H. Generation times and modeling of enterotoxin-positive and enterotoxin-negative strains of Clostridium perfringens in laboratory media and ground beef[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 1995, 58(12): 1303-1306. DOI: 10.1093/ps/80.6.813.

[9] ALNOMAN M, UDOMPIJITKUL P, PAREDES-SABJA D, et al. The inhibitory effects of sorbate and benzoate against Clostridium perfringens type A isolates[J]. Food Microbiology, 2015, 48: 89-98. DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.12.007.

[10] SAKURAI J, DUNCAN C L. Effect of carbohydrates and control of culture pH on beta toxin production by Clostridium perfringens type C[J]. Microbiology and Immunology, 1979, 23(5): 313-318. DOI: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1979.tb00468.x.

[11] JUNEJA V K, MARKS H, THIPPAREDDI H. Predictive model for growth of Clostridium perfringens during cooling of cooked uncured beef[J]. Food Microbiology, 2008, 25(1): 42-55. DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2007.08.004.

[12] HUANG L. Estimation of growth of Clostridium perfringens in cooked beef under fluctuating temperature conditions[J]. Food Microbiology, 2003, 20(5): 549-559. DOI: 10.1016/s0740-0020(02)00155-7.

[13] SARKER M R, SHIVERS R P, SPARKS S G, et al. Comparative experiments to examine the effects of heating on vegetative cells and spores of Clostridium perfringens isolates carrying plasmid genes versus chromosomal enterotoxin genes[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66(8): 3234-3240. DOI: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5549-5549.2000.

[14] LI J, MCCLANE B A. Comparative effects of osmotic, sodium nitrite-induced, and pH-induced stress on growth and survival of Clostridium perfringens type A isolates carrying chromosomal or plasmid-borne enterotoxin genes[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(12): 7620-7625. DOI: 10.1128/aem.01911-06.

[15] PAREDES-SABJA D, GONZALEZ M, SARKER M R, et al. Combined effects of hydrostatic pressure, temperature, and pH on the inactivation of spores of Clostridium perfringenstype A and Clostridium sporogenes in buffer solutions[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2007, 72(6): M202-M206. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00423.x.

[16] SONGER J G, UZAL F A. Clostridial enteric infections in pigs[J]. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 2005, 17(6): 528-536. DOI: 10.1177/104063870501700602.

[17] McCLANE B A. Clostridium perfringens[M]. Food Science and Technology New York Marcel Dekker, 2003: 91-104. DOI: 10.1128/9781555815912.ch19.

[18] MIWA N, NISHINA T, KUBO S, et al. Most probable numbers of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens in intestinal contents of domestic livestock detected by nested PCR[J]. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 1997, 59(7): 557-560. DOI: 10.1292/jvms.59.557.

[19] GRASS J E, GOULD L H, MAHON B E. Epidemiology of foodborne disease outbreaks caused by Clostridium perfringens, United States, 1998—2010[J]. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 2013, 10(2): 131-136. DOI: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1316.

[20] MIKI Y, MIYAMOTO K, KANEKO-HIRANO I, et al. Prevalence and characterization of enterotoxin gene-carrying Clostridium perfringens isolates from retail meat products in Japan[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 74(17): 5366-5372. DOI: 10.1128/aem.00783-08.

[21] ALLAART J G, van ASTEN A J A M, GR?NE A. Predisposing factors and prevention of Clostridium perfringens: associated enteritis[J]. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2013, 36(5): 449-464. DOI: 10.1016/j.cimid.2013.05.001.

[22] LI L, VALENZUELA-MARTINEZ C, REDONDO M, et al. Inhibition of Clostridium perfringens spore germination and outgrowth by lemon juice and vinegar product in reduced NaCl roast beef[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2012, 77(11): M598-M603. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02922.x.

[23] ARAS Z, HADIMLI H H. Detection and molecular typing of Clostridium perfringens isolates from beef, chicken and turkey meats[J]. Anaerobe, 2015, 32: 15-17. DOI: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.11.004.

[24] MORERA J, RODR-GUEZ E, GAMBOA M M. Determination of Clostridium perfringens in pork sausages from the Metropolitan area of Costa Rica[J]. Archivos Latinoamericanos De Nutrición, 1999, 49(3): 279-282.

[25] STAGNITTA P V, MICALIZZI B, GUZMáN A M S D. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens in meats in San Luis, Argentina[J]. Anaerobe, 2002, 8(5): 253-258. DOI: 10.1006/anae.2002.0433.

[26] WEN Q, Mc CLANE B A. Detection of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringenstype A isolates in American retail foods[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2004, 70(5): 2685-2691. DOI: 10.1128/aem.70.5.2685-2691.2004.

[27] YUAN-TONG L, RONALD L. Enterotoxigenicity and genetic relatedness of Clostridium perfringens isolates from retail foods in the United States[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(3): 1642-1646. DOI: 10.1128/aem.69.3.1642-1646.2003.

[28] BENNETT S D, WALSH K A, L HANNAH G. Foodborne disease outbreaks caused by Bacillus cereus, Clostridium perfringens, and Staphylococcus aureus-United States, 1998—2008[J]. Clinical Infectious Diseases An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 2013, 57(3): 425-433. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cit244.

[29] MCCLURE P J, KERRY J, KERRY J, et al. Microbiological hazard identification in the meat industry[C]//Meat Processing: Improving Quality, 2002: 217-236. DOI: 10.1533/9781855736665.2.217.

[30] DOYLE E. Survival and growth of Clostridium perfringens during the cooling step of thermal processing of meat products: a review of the scientific literature[R]. University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706: Food Research Institute. 2002.

[31] VELUGOTI PR, RAJAGOPAL L, JUNEJA V, et al. Use of calcium, potassium, and sodium lactates to control germination and outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens spores during chilling of injected pork[J]. Food Microbiology, 2007, 24(7): 687-694. DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2007.04.004.

[32] VALENZUELA-MARTINEZ C, PENA-RAMOS A, JUNEJA V K, et al. Inhibition of Clostridium perfringensspore germination and outgrowth by buffered vinegar and lemon juice concentrate during chilling of ground turkey roast containing minimal ingredients[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2010, 73(3): 470-476.

[33] XIAO Y, WAGENDORP A, ABEE T, et al. Differential outgrowth potential of Clostridium perfringens food-borne isolates with various cpe-genotypes in vacuum-packed ground beef during storage at

12 ℃[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2015, 194C: 40-45.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.11.008.

[34] JUNEJA V K, MAJKA W M. Outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens spores in cook-in-bag beef products[J]. Journal of Food Safety, 1995, 15(1): 21-34. DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-4565.1995.tb00118.x.

[35] NIETO-LOZANO J C, REGUERA-USEROS J I. The effect of the pediocin PA-1 produced by Pediococcus acidilactici against Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium perfringens in Spanish dry-fermented sausages and frankfurters[J]. Food Control, 2010, 21(5): 679-685.

[36] MIKELSAAR M, ZILMER M. Lactobacillus fermentum ME-3: an antimicrobial and antioxidative probiotic[J]. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 2009, 21(1): 1-27. DOI: 10.3402/mehd.v21i1.7573.

[37] HOA N T, BACCIGALUPI L, HUXHAM A, et al. Characterization of Bacillus species used for oral bacteriotherapy and bacterioprophylaxis of gastrointestinal disorders[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66(12): 5241-5247. DOI: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5241-5247.2000.

[38] SAARELA M, MOGENSEN G, FOND N R, et al. Probiotic bacteria: safety, functional and technological properties[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2000, 84(3): 197-215. DOI: 10.1016/s0168-1656(00)00375-8.

[39] CROST E, PUJOL A, LADIR M, et al. Production of an antibacterial substance in the digestive tract involved in colonization-resistance against Clostridium perfringens[J]. Anaerobe, 2010, 16(6): 597-603. DOI: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.06.009.

[40] KIM P I, MIN Y J, CHANG Y H, et al. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains isolated from porcine gastrointestinal tract[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2007, 74(5): 1103-1111. DOI: 10.1007/s00253-006-0741-7.

[41] RINKINEN M, WESTERMARCK E, SALMINEN S, et al. Absence of host specificity for in vitro adhesion of probiotic lactic acid bacteria to intestinal mucus[J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2004, 97(1): 55-61. DOI: 10.1016/s0378-1135(03)00183-4.

[42] 阳艳林, 肖建根. 不同枯草芽孢杆菌制剂对产气荚膜梭菌的抑制作用[J]. 中国畜牧杂志, 2011, 47(12): 55-56.

[43] 黄广明, 张媛媛, 鄢红国, 等. 3省份猪场产气荚膜梭菌感染状况的调查分析[J]. 养猪, 2014, 1(1): 103-104. DOI: 10.13257/j.cnki.21-1104/s.2014.01.001.

[44] SATHISHKUMAR J, GOKILA T, HANNAH K, et al. Bacillus subtilis PB6 improves intestinal health of broiler chickens challenged with Clostridium perfringens-induced necrotic enteritis[J]. Poultry Science, 2013, 92(2): 370-374. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2012-02528.

[45] KLOSE V, BAYER K, BRUCKBECK R, et al. In vitro antagonistic activities of animal intestinal strains against swine-associated pathogens[J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2010, 144(3): 515-521. DOI: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.02.025.

[46] BIAGI G, PIVA A, MOSCHINI M, et al. Performance, intestinal microflora, and wall morphology of weanling pigs fed sodium butyrate[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2007, 85(5): 1184-1191. DOI: 10.2527/jas.2006-378.

[47] GIBSON G R, BEATTY E R, WANG X, et al. Selective stimulation of bifidobacteria in the human colon by oligofructose and inulin[J]. Gastroenterology, 1995, 108(4): 975-982. DOI: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90192-2.

[48] SWANSON K S, GRIESHOP C M, BAUER L L, et al. Supplemental fructooligosaccharides and mannano-ligosaccharides influence immune function, ileal and total tract nutrient digestibilities, microbial populations and concentrations of protein catabolites in the large bowel of dogs[J]. Journal of Nutrition, 2002, 132(5): 980-989.

[49] BIGGS P, PARSONS C, FAHEY G. The effects of several oligosaccharides on growth performance, nutrient digestibilities, and cecal microbial populations in young chicks[J]. Poultry Science, 2007, 86(11): 2327-2336. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2007-00427.

[50] FLICKINGER E A, JAN V L, FAHEY G C. Nutritional responses to the presence of inulin and oligofructose in the diets of domesticated animals: a review[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2003, 43(1): 19-60. DOI: 10.1080/10408690390826446.

[51] GóMEZ-CONDE M S, GARCíA J, CHAMORRO S, et al. Neutral detergent-soluble fiber improves gut barrier function in twenty-five-day-old weaned rabbits[J]. Journal of Animal Science, 2007, 85(12): 3313-3321. DOI: 10.2527/jas.2006-777.

[52] SHINOHARA K, OHASHI Y, KAWASUMI K, et al. Effect of apple intake on fecal microbiota and metabolites in humans[J]. Anaerobe, 2010, 16(5): 510-515. DOI: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.03.005.

[53] MCREYNOLDS J L, BYRD J A, GENOVESE K J, et al. Dietary lactose and its effect on the disease condition of necroticenteritis[J]. Poultry Science, 2007, 86(8): 1656-1661. DOI: 10.1093/ps/86.8.1656.

[54] NORHANA M N W, POOLE S E, DEETH H C, et al. Effects of nisin, EDTA and salts of organic acids on Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella and native microflora on fresh vacuum packaged shrimps stored at 4 ℃[J]. Food Microbiology, 2012, 31(1): 43-50. DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.01.007.

[55] HARMAYANI E, SOFOS J N, SCHMIDT G R. Fate of Listeria monocytogenes in raw and cooked ground beef with meat processing additives[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 1993, 18(3): 223-232. DOI: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90047-k.

[56] SCHLYTER J H, GLASS K A, LOEFFELHOLZ J, et al. The effects of diacetate with nitrite, lactate, or pediocin on the viability of Listeria monocytegenes in turkey slurries[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 1993, 19(4): 271-281. DOI: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90019-d.

[57] BIGGS P, PARSONS C. The effects of several organic acids on growth performance, nutrient digestibilities, and cecal microbial populations in young chicks[J]. Poultry Science, 2008, 87(12): 2581-2589. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2008-00080.

[58] THIPPAREDDI H, JUNEJA V, PHEBUS R K, et al. Control of Clostridium perfringens germination and outgrowth by buffered sodium citrate during chilling of roast beef and injected pork[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2003, 66(3): 376-381.

[59] SAEED A, DANIEL P S, SARKER M R. Inhibitory effects of polyphosphates on Clostridium perfringens growth, sporulation and spore outgrowth[J]. Food Microbiology, 2008, 25(6): 802-808. DOI: 10.1016/j.fm.2008.04.006.

[60] BALCIUNAS E M, MARTINEZ F A C, TODOROV S D, et al. Novel biotechnological applications of bacteriocins: a review[J]. Food Control, 2013, 32(1): 134-142. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.11.025.

[61] GARDE S, GóMEZ-TORRES N, HERNáNDEZ M, et al. Susceptibility of Clostridium perfringens to antimicrobials produced by lactic acid bacteria: reuterin and nisin[J]. Food Control, 2014, 44: 22-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.03.034.

[62] MARTA A, NATALIA G T, MARTA H, et al. Inhibitory activity of reuterin, nisin, lysozyme and nitrite against vegetative cells and spores of dairy-related Clostridium species[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 172(7): 70-75. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.12.002.

[63] UDOMPIJITKUL P, PAREDES-SABJA D, SARKER M R. Inhibitory effects of nisin against Clostridium perfringensfood poisoning and nonfood-borne isolates[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2012, 77(1): M51-M56. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02475.x.

[64] GRILLI E, MESSINA MR, CATELLI E, et al. Pediocin A improves growth performance of broilers challenged with Clostridium perfringens[J]. Poultry Science, 2009, 88(10): 2152-2158. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2009-00160.

[65] SPELHAUGS R, HARLANDERS K. Inhibition of foodborne bacterial pathogens by bacteriocins from Lactococcus lactis and Pediococcus pentosaceous[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 1989, 52(12): 856-862.

[66] CINTAS L M, CASAUS P, HAVARSTEIN L S, et al. Biochemical and genetic characterization of enterocin P, a novel sec-dependent bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium P13 with a broad antimicrobial spectrum[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1997, 63(11): 4321-4330.

[67] BIZANI D, BRANDELLI A. Characterization of a bacteriocin produced by a newly isolated Bacillus sp. strain 8 A[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2002, 93(3): 512-519. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01720.x.

[68] XIE J, ZHANG R, SHANG C, et al. Isolation and characterization of a bacteriocin produced by an isolated Bacillus subtilis LFB112 that exhibits antimicrobial activity against domestic animal pathogens[J]. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2009, 8(20): 5611-5619.

[69] JUNEJA V K, DWIVEDI H P, YAN X. Novel natural food antimicrobials[J]. Annual review of Food Science and Technology, 2012, 3: 381-403. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101241.

[70] TIWARI B K, VALDRAMIDIS V P, ODONNELL C P, et al. Application of natural antimicrobials for food preservation[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2009, 57(14): 5987-6000. DOI: 10.1079/9781845937690.0204.

[71] NIETO-LOZANO J C, REGUERA-USEROS J I, PELAEZ-MARTINEZ M D C, et al. Effect of a bacteriocin produced by Pediococcus acidilactici against Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium perfringens on Spanish raw meat[J]. Meat Science, 2006, 72(1): 57-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.06.004.

[72] ZHANG J, LIU G, SHANG N, et al. Purification and partial amino acid sequence of pentocin 31-1, an anti-Listeria bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus pentosus 31-1[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2009, 72(12): 2524-2529.

[73] GUO-JANE T, SAN-PIN H. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity of shrimp chitosan against some intestinal bacteria[J]. Fisheries Science, 2004, 70(4): 675-681. DOI: 10.1111/j.1444-2906.2004.00856.x.

[74] JUNEJA V K, HARSHAVARDHAN T, LATIFUL B, et al. Chitosan protects cooked ground beef and turkey against Clostridium perfringens spores during chilling[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2006, 71(6): M236-M240. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00109.x.

[75] AZIZ M A, CABRAL J D, BROOKS H J L, et al. Antimicrobial properties of a chitosan dextran-based hydrogel for surgical use[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2012, 56(1): 280-287. DOI: 10.1128/aac.05463-11.

[76] SANTOS G, MIRNA A, MARIVEL G, et al. Inhibition of growth, enterotoxin production, and spore formation of Clostridium perfringens by extracts of medicinal plants[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2002, 65(10):1667-1669.

[77] SI W, NI X, GONG J, et al. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and structurally related synthetic food additives towards Clostridium perfringens[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2009, 106(1): 213-220. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03994.x.

[78] AH Y J, SAKANAK S, KIM M J, et al. Effect of green tea extract on growth of intestinal bacteria[J]. Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 2009, 3(6): 335-338. DOI: 10.3402/mehd.v3i6.7559.

[79] BURT S. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods: a review[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2004, 94(3): 223-253. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.022.

[80] JUNEJA V K, BARI M L, INATSU Y, et al. Control of Clostridium perfringens spores by green tea leaf extracts during cooling of cooked ground beef, chicken, and pork[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2007, 70(6): 1429-1433.

[81] DEMIRCI F, GUVEN K, DEMIRCI B, et al. Antibacterial activity of two Phlomis essential oils against food pathogens[J]. Food Control, 2008, 19(12): 1159-1164. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.01.001.

[82] SEBRANEK J G, BACUS J N. Cured meat products without direct addition of nitrate or nitrite: what are the issues?[J]. Meat Science, 2007, 77(1): 136-147. DOI: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.03.025.