传粉网络非对称特化的地理模式

2016-07-21肖宜安李晓红张斯斯胡文海曹裕松

肖宜安, 李晓红, 张斯斯, 胡文海, 曹裕松, 董 鸣

1 井冈山大学生命科学学院,吉安 343009 2 江西省生物多样性与生态工程重点实验室,吉安 343009 3 杭州师范大学生态系统保护与恢复杭州市重点实验室,杭州 310036

传粉网络非对称特化的地理模式

肖宜安1,2, 李晓红1,2, 张斯斯1, 胡文海1,2, 曹裕松1,2, 董鸣3,*

1 井冈山大学生命科学学院,吉安343009 2 江西省生物多样性与生态工程重点实验室,吉安343009 3 杭州师范大学生态系统保护与恢复杭州市重点实验室,杭州310036

摘要:植物与传粉者间相互作用,构成了复杂的传粉网络。非对称特化是共生互作网络中的有趣现象和基本特点,也被认为是植物-传粉者互作网络的结构特征之一。根据文献总结分析了植物-传粉者互作网络非对称特化的重要名词术语,并采用线性回归法深入分析了植物-传粉者互作网络的地理变异模式,以及植物生活型和网络大小等传粉网络特征对非对称程度的影响。结果表明:传粉网络大小与网络的交互作用间呈线性正相关关系,并随总物种丰度呈指数增长。25个传粉网络的线性回归斜率(Lβ)变异范围在0.002至0.031间,且斜率值随植物丰度(P)、传粉者丰度(A)、总物种丰度(R)、交互作用(I)及网络大小(M)上升而降低。海拔高度对传粉网络非对称性有一定影响效果,而纬度的变化并不显著影响传粉网络非对称性。草本植物、灌木及乔木植物与其传粉者之间的相关系数分别为-0.197,-0.026和0.200,表明草本物种比乔木物种非对称性更强。

关键词:地理模式;植物-传粉者互作网络;非对称特化;非对称性程度;植物生活型

非对称特化是共生互作网络中有趣的现象和基本特点[1],对生物多样性保护具有重要意义[2]。非对称特化不仅存在于植物-传粉者交互作用中[2],在植物-果实散布者和植物-食草动物网络中[3]也有。与植物-食草动物网络相比,这种非对称特化在植物-传粉者网络[4]以及其他共生网络,比如鱼-寄生虫互作网络[5]、蚂蚁-植物网络[6]中更为频繁。植物-传粉者互作网络已被证明表现出种间相互作用的特定非对称组织[6- 7]。植物-传粉者互作网络合作者中的植物,往往表现为特化者,这些植物由已经更加适应传粉者访问的泛化传粉者传粉[2, 8];而特化传粉者主要为泛化植物传粉这一相反趋势也较为常见[2, 7]。所以,研究表明物种间的非对称特化可能比之前认为的更加普遍[9- 10]。

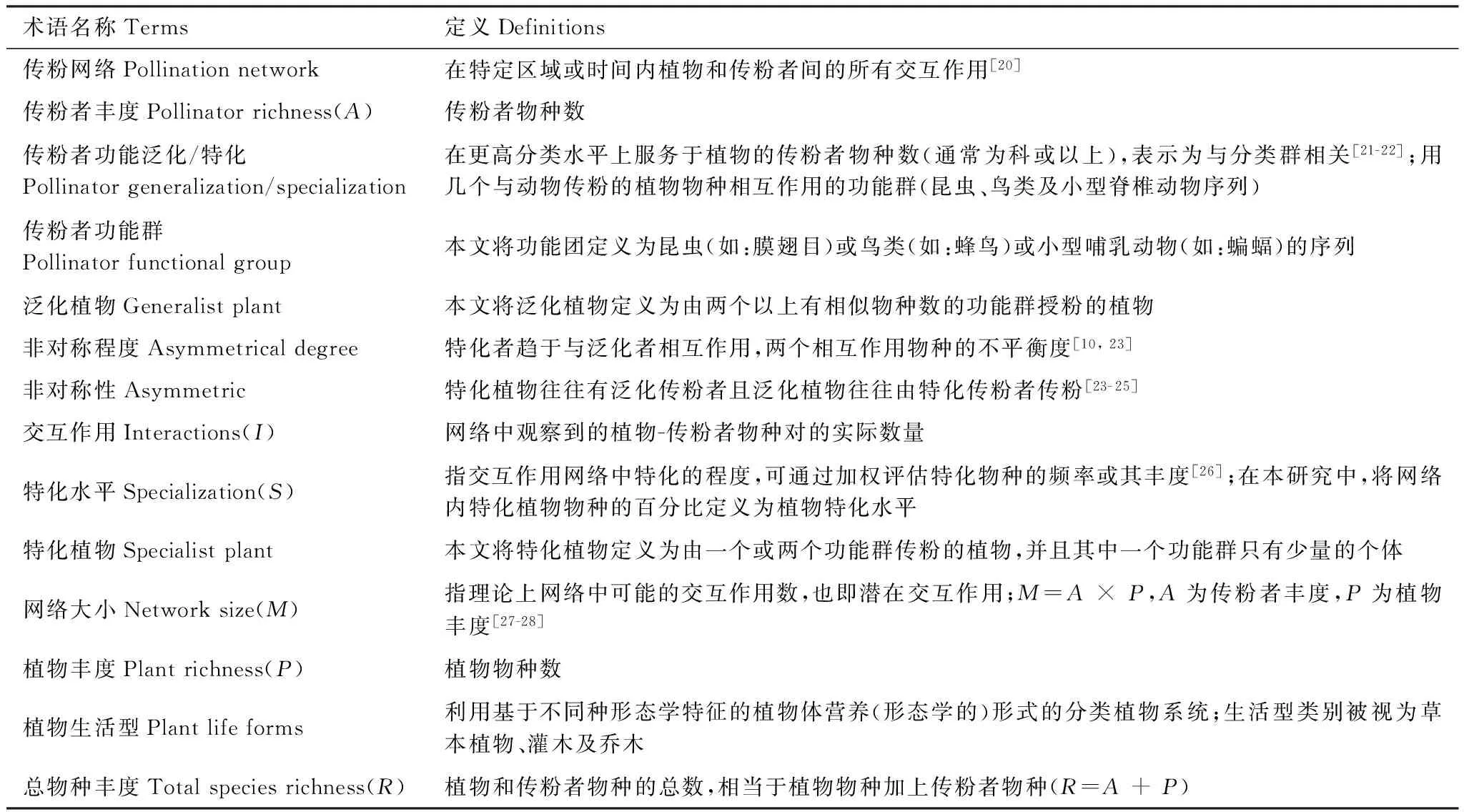

尽管植物-传粉者互作网络中的对称特化已有报道[11],但是非对称特化已被认为是植物-传粉者互作网络的一个结构特征[2-3, 12]。由于物种的广泛分布和丰度差异,群落中的非对称特征不但可以在宏观地理尺度上发生[10],而且其专一性和强度也存在时空变化[13]。近年来,对于非对称网络的认识,已经取得了一些重要进展[4, 14- 16]。许多研究[4, 17- 18]都认为,全球植物-传粉者互作网络大部分是非对称的。部分协同进化的研究主要关注成对或小群的物种,但其中大多数都强调群落内植物和传粉者间的关系,以及非对称性和物种丰度的关系。Vázquez等人[19]通过对43个共生和敌对互作网络进行研究后,提出“丰度-非对称性假说”,其主要意思是如果群落中个体随机相互作用,物种丰度会导致非对称结构。但对于如何理解非对称性网络的地理变异模式,以及传粉网络中传粉者丰度、植物丰度的动态变化(表1)、植物生活型等特征将如何影响非对称特化的相关研究,却少见报道。

表1 术语定义表

在本研究中,拟通过分析已发表论文的原始数据,重点阐明本文提出的以下假说:(1)热带地区的植物-传粉者网络比温带地区的植物-传粉者网络非对称性程度更强;(2)草本植物物种具有比乔木更强的非对称性。

1方法

1.1数据收集

所选用的25个传粉网络均从已发表论文及美国生态综合分析网站(http://www.nceas.ucsb.edu/interactionweb)(本文所分析的传粉网络基本情况及其参考文献见表2)。原始数据中,每个数据集由植物与其传粉者间的访问频率矩阵信息构成,其中第一行代表传粉者物种名称,第一列为植物物种名称。在本文,只关注二者间是否存在“互作关系”,因此上述所有数据集转换成一个二元交互矩阵。在该矩阵中,行代表传粉者物种,列代表植物物种;“1”和“0”分别代表相应行(传粉者物种)和列(植物物种)交叉单元内“有”和“无”交互作用。

表2 25个传粉网络的基本信息

1.2非对称度的量化

本文采用线性回归法来量化每个植物-传粉者网络的非对称强度。

首先,根据Bascompte等人[12]已经给出的上述传粉网络中每个物种对之间的非对称值(其范围为0到1),将每一个网络中所有植物-传粉者对的非对称值从小到大排列后,以非对称值为纵坐标、植物-传粉者对数为横坐标,进行线性模拟回归。定义该线性回归曲线的斜率值(Lβ)来体现某个传粉网络的非对称强度。根据斜率值大小来确定传粉网络的非对称性强度。即斜率值越低,则表明该传粉网络的非对称性强度越高。

然后再进一步分析非对称强度与物种丰度、网络大小、纬度及海拔高度因素间的关系。

1.3非对称程度与植物生活型的关系

对每个数据集中的植物物种的生活型(草本植物,灌木及乔木等3种类型)进行分析,然后利用相关系数法[2]对植物在物种层次上的非对称程度进行评估。

1.4极度特化的植物和传粉者的数量分析

对每个数据集,再进一步计算只由一个传粉者物种传粉的极度特化植物的数量和只对一个植物物种传粉的极度特化传粉者的数量。并进一步分析这些传粉者和植物的互作特征。

1.5统计分析

所有的统计分析用SPSS 17.0 统计软件(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)完成。采用回归分析模型模拟各个传粉网络的线性回归曲线的斜率值(Lβ)与传粉网络的物种丰度、互作网络大小等参数间的关系,并进一步分析其对非对称性程度的影响。用线性回归模型分析纬度、海拔高度等对非对称性程度的影响。

2结果与分析

2.1传粉网络的组成

属于5个广义生物地理学范畴的25个植物-传粉网络的数据共包括4004个传粉者物种及971个植物物种(包括各传粉网络间的重复物种)(表2)。植物丰度(P)及传粉者丰度(A)的范围分别为7—115和12—889,网络互作数量(I)在31和1975之间变化,其网络大小(M)的范围为120—102235。网络大小与互作数量间呈线性正相关关系(M=52.619I-7235.796;F1, 24=282.004,P<0.0001),并随物种丰度(R)呈指数增长(M=96.922I-6852.408;F1, 24=701.746,P<0.0001),物种丰度在22和1004间变化。

2.2传粉网络大小对非对称性的影响

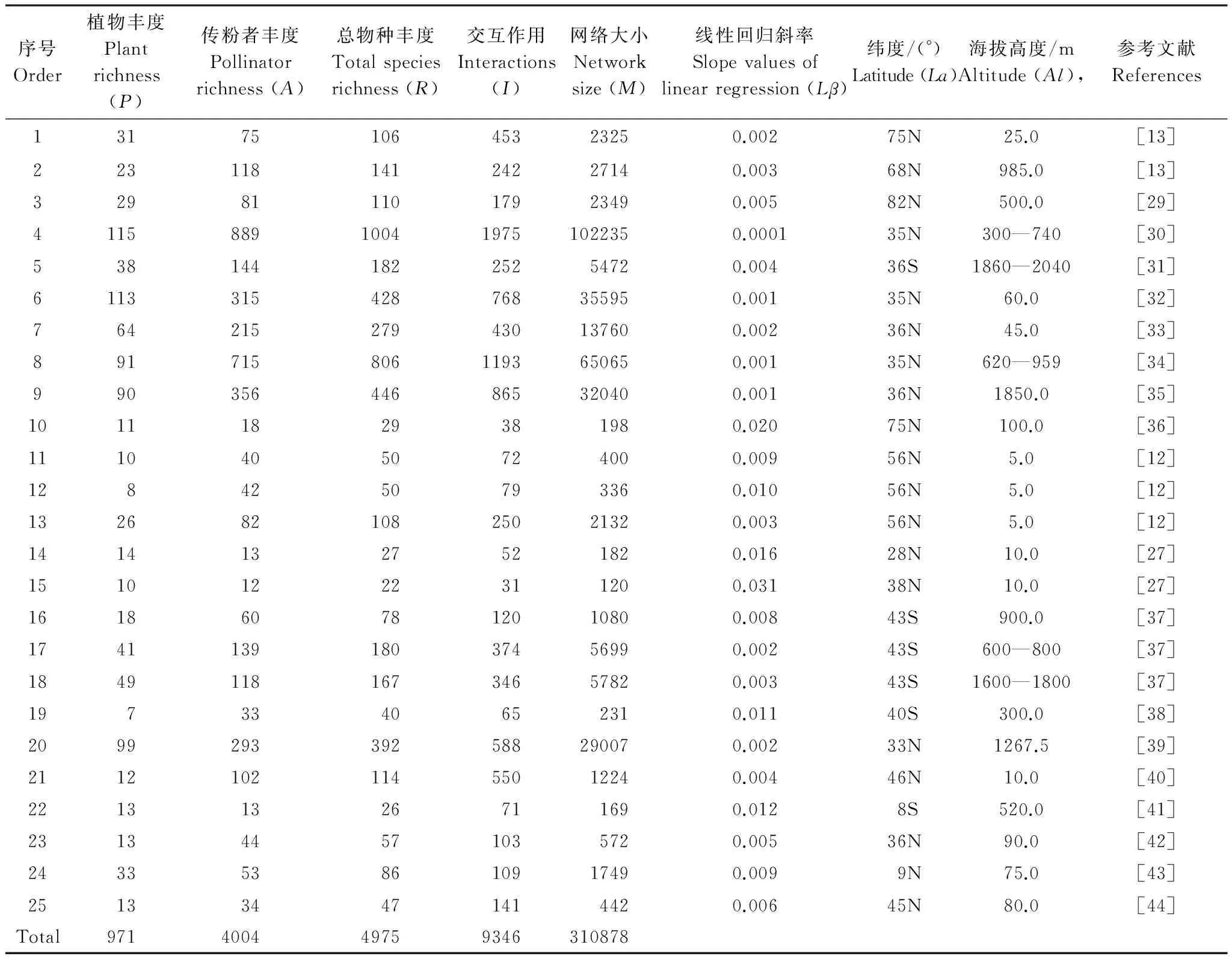

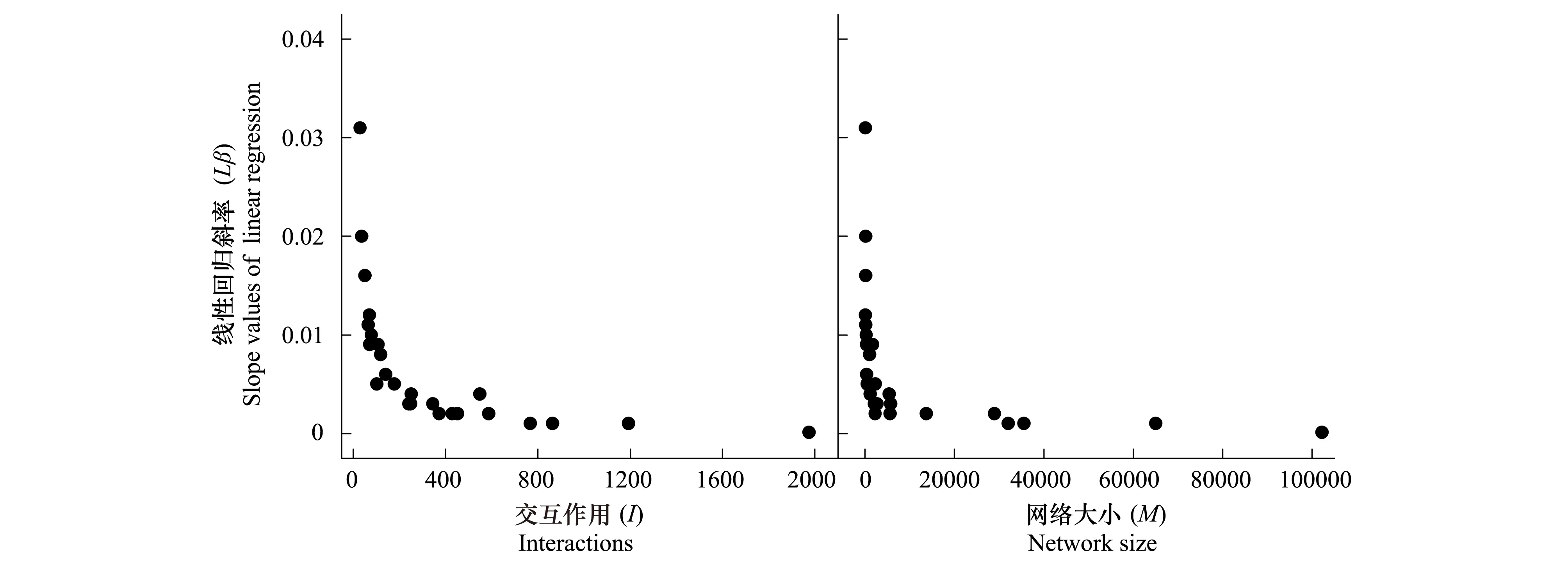

25个传粉网络的斜率(Lβ)变异范围在0.002至0.031间,且斜率随植物丰度(P)、传粉者丰度(A)、物种丰度(R)、互作数(I)以及网络大小(M)上升而降低(表2,图1,图2)。表明,这些参数与传粉网络的非对称性强度呈负相关关系。

图1 植物丰度(P),传粉者丰度(A),总物种丰度(R)与线性回归斜率(Lβ)之间的关系Fig.1 The relationship between slope values of linear regression (Lβ) and plant richness (P), pollinator richness (A), total species richness (R) 植物丰度(P): Lβ=-0.005 ln(P) + 0.024, F1,24=18.008, P<0.0001; 传粉者丰度(A): Lβ=-0.005 ln(A) + 0.028, F1,24=41.92, P<0.0001; 总物种丰度(R): Lβ=-0.005 ln(R) + 0.031, F1,24=36.014, P<0.0001

图2 交互作用(I),网络大小(M)与线性回归斜率(Lβ)之间的关系Fig.2 The relationship between slope values of linear regression (Lβ) and interactions (I), network size (M)交互作用(I): Lβ=-0.005 ln(I) + 0.035, F1,24=53.893, P<0.0001;网络大小(M): Lβ=-0.003 ln(M) + 0.028, F1,18=32.713, P<0.0001

2.3纬度及海拔高度对非对称性的影响

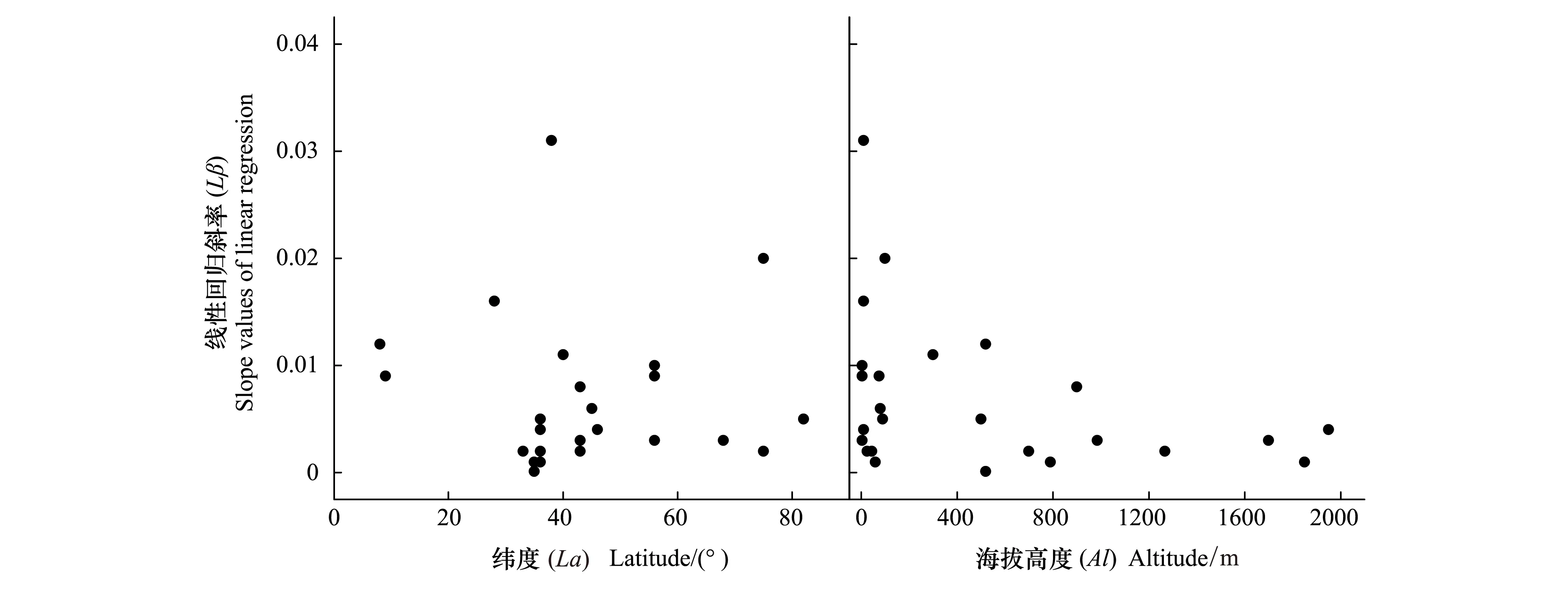

本研究涉及的传粉网络跨越较大纬度范围,从8° S到82° N,但大多数在30—45°间。将纬度和海拔高度分别作为独立变量进行分析,结果表明:Lβ随海拔高度上升而略微降低(P=0.053),表明海拔高度对传粉网络非对称性有一定的影响效果,然而纬度的变化并不显著影响传粉网络的非对称性(P=0.618)(图3)。

图3 纬度(La),海拔高度(Al)与线性回归斜率(Lβ)之间的关系Fig.3 The relationship between slope values of linear regression (Lβ) and Latitude (la), Altitude (Al)纬度(La),海拔高度(Al)及线性回归斜率(Lβ)间没有显著关系(Lβ=-0.001 ln(La) + 0.012, F1,24=0.256, P<0.618; Lβ=-0.001 ln(Al) + 0.013, F1,24=4.153, P<0.053)

2.4非对称与植物生活型

本研究中,仅仅分析出了19个植物-传粉者互作网络中的505种植物的生活型(包括不同网络中的重复物种),其中草本106种,灌木361种,乔木38种。结果表明,草本植物、灌木及乔木植物与其传粉者之间的相关系数分别为-0.197,-0.026和0.200(图4)。也就是说,草本物种比乔木物种非对称性更强。

图4 在观察的植物-传粉者互作网络中不同生活型间一个植物物种的访问物种数量(nvis)与植物物种的访问物种交互作用数量(mvis)间的关系Fig.4 The relationship between Mean number of interactions of the visitor species of a plant species (mvis) and Number of pollinator species of a plant species (nvis)每个数据点代表一种植物; 草本植物Herb (mvis=-0.1768 nvis + 10.265, R2=0.039, n=361); 灌木Shrub (mvis=-0.0139 nvis + 6.1201, R2=0.0007, n=106); 乔木Tree (mvis=0.1022 nvis + 4.0624, R2=0.0398, n=38)

2.5极度特化的植物和传粉者

所有传粉网络总共包含4004个传粉者物种(包括各传粉网络的重复物种),其中1802个传粉者物种分别只对一种植物传粉。由这些传粉者传粉的植物中,却只有12种植物(占全部植物种数的0.55%)是仅仅拥有一个传粉者的极度特化植物。其余2202种传粉者中,有1801种(占81.79%)拥有超过10种传粉服务对象,而这其中的181种(占10.05%)传粉者拥有超过100种传粉服务对象。

在971种植物中,有160种植物(占全部植物种数的18.41%)只由一种传粉者传粉。而对这些植物进行传粉的传粉者中,只有13个传粉者(8.13%)分别只对一种植物传粉。67种植物(41.88%)拥有10种传粉者,23种植物分别拥有20种以上的传粉者。

3讨论

本文分析结果表明传粉网络交互作用数量随物种丰度及网络大小呈指数增长。传粉网络的非对称程度随物种丰度(包括植物和传粉者)、网络交互作用的数量及网络大小的上升而下降。传粉网络的网络大小和非对称性之间可能是因为在物种匮乏群落中,与泛化物种互作时缺乏充足的物种[6];或者,物种匮乏群落是一种已经失去其特化物种的退化系统。已有少量研究也得出了类似的结论[3-4,10]。这些作者使用一些类似“null models”探讨了植物-动物互作网络的作用模式和特征,包括植物-传粉者互作网络的非对称性。采用该方法评价和探明传粉网络的特定结构及其相关假设,首先必须构建合适的“null models”[4],这是该方法使用的前提和基础。但如何构建合理的模型,却成了许多研究人员遇到的难题。因此该方法的使用也受到许多限制。而本文则用了线性回归法证实了这一现象。这表明,线性回归法是一个分析传粉群落的非对称程度的简单而直接的有效方法,对于揭示了传粉互作网络中非对称特化的趋势具有明显优势。

本文研究结果还显示,纬度与传粉网络的特化程度之间没有显著相关性。另一项研究结果表明,植物物种在热带地区更特化,而在高纬度地区(比如温带、寒带)泛化[45]。而大多数研究表明,越特化的网络则表现出更强的非对称性[19]。这似乎又表明热带地区的传粉网络要比温带地区的具有更强的非对称性。因此,综合上述分析和本文的结果,似乎表明传粉网络的非对称性程度可能仅在一定程度上受到纬度和海拔高度的影响,这一结果也进一步支持了线性回归法的可行性和优势。

本文结果还表明,草本植物比木本植物表现出更强的非对称性。其原因可能是草本植物比木本植物表现出更高的特化水平。一个主要的解释是,传粉网络非对称特化模式与网络中物种间丰度分布相关,也可能是因为个体间的随机互作所致[5, 19]。特化的植物往往具有更高的灭绝风险[11]和更低的适合度[10]。尤其是当丰度、访问频率或者交互作用数量发生激烈变异时,将更有利于泛化者;相反当环境相对稳定时,则有利于特化者[46]。但是,这还需要大量的直接证据来进一步阐明其过程和模式。

总之,本文提供了传粉网络非对称性研究的新方法,以及传粉网络非对称程度与网络大小、纬度及植物生活型间关系的重要认识。

参考文献(References):

[1]Campbell C, Yang S, Albert R, Shea K. A network model for plant-pollinator community assembly. Proceedings of the National Academyof Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(1): 197- 202.

[2]Stang M, Klinkhamer P G L, van der Meijden E.Asymmetric specialization and extinction risk in plant-flower visitor webs: a matter of morphology or abundance?. Oecologia, 2007, 151(3): 442- 453.

[3]Bascompte J P, Jordano C J, Melián C J, Olesen J M. The nested assembly of plant-animal mutualistic networks. Proceedings of the National Academyof Sciences of the United States of America, 2003, 100(16): 9383- 9387.

[4]Thébault E, Fontaine C.Does asymmetric specialization differ between mutualistic and trophic networks?. Oikos, 2008, 117(4): 555- 563.

[5]Vázquez D P, Poulin R, Krasnov B R, Shenbrot G I. Species abundance and the distribution of specialization in host-parasite interaction networks. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2005, 74(5): 946- 955.

[6]Guimarães P R, Rico-Gray J V, dos Reis S F, Thompson J N. Asymmetries in specialization in ant-plant mutualistic networks.Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2006, 273(1597): 2041- 2047.

[7]Jensen K. Generalization and Specialization in Tropical Pollination Systems [D]. Aarhus, Denmark: University of Aarhus, 2005.

[8]Jordano P. Patterns of mutualistic interactions in pollination and seed dispersal: connectance, dependence asymmetries, and coevolution.The American Naturalist, 1987, 129(5): 657- 677.

[9]Saavedra S, Reed-Tsochas F, Uzzi B. Asymmetric disassembly and robustness in declining networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(43): 16466- 16471.

[10]Vázquez D P, Aizen M A. Asymmetric specialization: A pervasive feature of plant-pollinator interactions. Ecology, 2004, 85(5): 1251- 1257.

[11]Vázquez D P, Simberloff D. Ecological specialization and susceptibility to disturbance: conjectures and refutations. The American Naturalist, 2002, 159(6): 606- 623.

[12]Bascompte J, Jordano P, Olesen J M. Asymmetric coevolutionary networks facilitate biodiversity maintenance. Science, 2006, 312(5772): 431- 433.

[13]Eiberling H, Oiesen J M.The structure of a high latitude plant-flower visitor system: the dominance of flies. Ecography, 1999, 22(3): 314- 323.

[14]Kokkoris G D, Troumbis A Y, Lawton J H. Patterns of species interaction strength in assembled theoretical competition communities.Ecology Letters, 1999, 2(2): 70- 74.

[15]Bascompte J, Jordano P, Olesen J M. Response tocomment on “Asymmetric coevolutionary networks facilitate biodiversity maintenance”. Science, 2006, 313(5795): 1887- 1887.

[16]Holland J N, Okuyama T, DeAngelis D L. Comment on “Asymmetric coevolutionary networks facilitate biodiversity maintenance”. Science, 2006, 313(5795): 1887- 1887.

[17]Jordano P, Bascompte J, Olesen J M. Invariant properties in coevolutionary networks of plant-animal interactions.Ecology Letters, 2003, 6(1): 69- 81.

[18]Vázquez D P, Aizen M A. Null model analyses of specialization in plant-pollinator interactions. Ecology, 2003, 84(9): 2493- 2501.

[19]Vázquez D P, Melián C J, Williams N M, Blüthgen N, Krasnov B R, Poulin R. Species abundance and asymmetric interaction strength in ecological networks. Oikos, 2007, 116(7): 1120- 1127.

[20]Menz M H M, Phillips R D, Winfree R, Kremen C, Aizen M A, Johnson S D, Dixon K W. Reconnecting plants and pollinators: challenges in the restoration of pollination mutualisms. Trendsin Plant Science, 2011, 16(1): 4- 12.

[21]Fenster C B, Armbruster W S, Wilson P, Dudash M R, Thomson J D. Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2004, 35: 375- 403.

[22]Ollerton J, Killick A, Lamborn E, Watts S, Whiston M. Multiple meanings and modes: on the many ways to be a generalist flower. Taxon, 2007, 56(3): 717- 728.

[23]Vázquez D P, Blüthgen N, Cagnolo L, Chacoff N P. Uniting pattern and process in plant-animal mutualistic networks: a review. Annals of Botany, 2009, 103(9): 1445- 1457.

[24]Strauss S Y, Irwin R E.Ecological and evolutionary consequences of multispecies plant-animal interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2004, 35: 435- 466.

[25]Ollerton J. “Biological Barter”: patterns of specialization compared across different mutualisms // Waser N M, Ollerton J, eds. Plant-Pollinator Interactions: from Specialization to Generalization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006: 411- 435.

[26]Heithaus E R. Flower- feeding specialization in wild bee and wasp communities in seasonal neotropical habitats. Oecologia, 1979, 42(2): 179- 194.

[27]Olesen J M, Eskildsen L I, Venkatasamy S. Invasion of pollination networks on oceanic islands: importance of invader complexes and endemic super generalists. Diversity and Distributions, 2002, 8(3): 181- 192.

[28]de Mendonça Santos G M, Aguiar C M L, Mello M A R. Flower-visiting guild associated with the Caatinga flora: trophic interaction networks formed by social bees and social wasps with plants. Apidologie, 2010, 41(4): 466- 475.

[29]Hocking B. Insect flower associations in the high Arctic with special reference to nectar. Oikos, 1968, 19(2): 359- 387.

[30]Inoue T, Kato M, Kakutani T, Suka T, Itino T. Insect-flower relationship in the temperate deciduous forest of Kibune, Kyoto: An overview of the flowering phenology and the seasonal pattern of insect visits. Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University, 1990, 27(4): 377- 463.

[31]Inouye D W, Pyke G H. Pollination biology in the Snowy Mountains of Australia: comparisons with montane Colorado. Australian Journal of Ecology, 1988, 13(2): 191- 205.

[32]Kakutani T, Inoue T, Kato M, Ichihashi H. Insect-flower relationship in the campus of Kyoto University, Kyoto: An overview of the flowering phenology and the seasonal pattern of insect visits. Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University, 1990, 27(4): 465- 522.

[33]Kato M, Miura R. Flowering phenology and anthophilous insect community at a threatened natural lowland marsh at Nakaikemi in Tsuruga, Japan. Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University, 1996, 29(1): 1- 48.

[34]Kato M, Kakutani T, Inoue T, Itino T. Insect flower relationship in the primary beech forest of Ashu, Kyoto: An overview of the flowering phenology and the seasonal pattern of insect visits. Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University, 1990, 27: 309- 375.

[35]Kato M, Matsumoto M, Kato T. Flowering phenology and anthophilous insect community in the cool-temperate subalpine forests and meadows at Mt. Kushigata in thecentral part of Japan. Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University, 1993, 28: 119- 172.

[36]Mosquin T, Martin J E H. Observations on the pollination biology of plants on Melville Island, N. W. T., Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist, 1967, 81: 201- 205.

[37]Primack R B. Insect pollination in the New Zealand mountain flora. New Zealand Journal Botany, 1983, 21(3): 317- 333.

[38]Schemske D, Willson M F, Melampy M, Miller L, Verner L, Schemske K, Best L. Flowering ecology of some spring woodland herbs. Ecology, 1978, 59(2): 351- 366.

[39]Yamazaki K, Kato M. Flowering phenology and anthophilous insect community in a grassland ecosystem at Mt. Yufu, Western Japan. Contributions from the Biological Laboratory, Kyoto University, 2003, 29(3): 255- 318.

[40]Barret S C H, Helenurm K. The reproductive-biology of boreal forest herbs. I. Breeding systems and pollination. Canadian Journal of Botany, 1987, 65(10): 2036- 2046.

[41]Bezerra1 E L S, Machadol I C, Mello M A R. Pollination networks of oil-flowers: a tiny world within the smallest of all worlds. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2009, 78(5): 1096- 1101.

[42]Motten A F. Pollination ecology of the spring wildflower community in the deciduous forests of piedmont North Carolina [D]. Durham, North Carolina, USA: Duke University, 1982.

[43]Ramirez N, Brito Y. Pollination biology in a palm swamp community in the Venezuelan Central Plains. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 1992, 110(4): 277- 302.

[44]Small E. Insect pollinators of the Mer Bleue peat bog of Ottawa. Canadian Field Naturalist, 1976, 90: 22- 28.

[45]肖宜安, 张斯斯, 闫小红, 董鸣. 全球气候变暖影响植物-传粉者网络的研究进展. 生态学报, 2015, 35(12):3871-3880.

[46]Waser N M, Chittka L, Price M V, Williams N M, Ollerton J. Generalization in pollination systems, and why it matters. Ecology, 1996, 77(4): 1043- 1060.

Geographic pattern of asymmetric specialization in plant-pollinator interaction network

XIAO Yi′an1,2, LI Xiaohong1,2, ZHANG Sisi1, HU Wenhai1,2, CAO Yusong1,2, DONG Ming3,*

1CollegeofLifeSciences,JinggangshanUniversity,Ji′an343009,China2KeyLaboratoryforBiodiversityScienceandEcologicalEngineering,Ji′an343009,China3KeyLaboratoryofHangzhouCityforEcosystemProtectionandRestoration,HangzhouNormalUniversity,Hangzhou310036,China

Abstract:Pollination network results from the interactions between plants and their pollinators. Asymmetric specialization characterizes symbiotic interaction, and it is regarded among the structural characters of the network. To date, important progress has been made in recognizing asymmetry of the networks, but there was hardly any progress about the geographic variation and asymmetric specialization of the network as well as about the effects of plant life-form on the asymmetric specialization. Here, we summarized a number of concepts used for asymmetric specialization according to available literature and analyzed the geographic variation pattern of the networks as well as the relation of asymmetric specialization of the network to plant life-form and network size using linear regression based on data collected from published papers. We found that the network size is positively linearly correlated with network interaction and that it expressed an exponential increase with total richness of plant species. For all 25 networks investigated, the slope of linear regression (Lb) of the network ranged from 0.002 to 0.031 and it was negatively significantly correlated with plant richness (P), pollinator richness (A), species richness (R), interactions (I), and network size (M). Lb slightly decreased with altitude (P=0.053 for the partial effect of altitude), whereas no effect of latitude (P=0.618) was observed. The correlation coefficients between pollinators and herbs, trees, and shrubs were -0.197, -0.026, and 0.200, respectively, indicating that asymmetric degree was higher in herbs than in trees. This paper provides a novel method to investigate the asymmetry of plant-pollinator interaction network as well as an insight into the relationship between asymmetric degree and network size, latitude, and plant life-form.

Key Words:geographic pattern; plant-pollinator interaction network; asymmetric specialization; asymmetrical degree; plant life-forms

基金项目:国家自然科学基金项目(31060069, 31360099); 教育部新世纪优秀人才支持计划(NCET-07-0385); 江西省自然科学基金项目(2010GZN0129); 江西省高水平学科(生物学)

收稿日期:2014- 11- 06; 网络出版日期:2015- 08- 24

*通讯作者

Corresponding author.E-mail: dongming@hznu.edu.cn

DOI:10.5846/stxb201411062201

肖宜安, 李晓红, 张斯斯, 胡文海, 曹裕松, 董鸣.传粉网络非对称特化的地理模式.生态学报,2016,36(9):2544- 2551.

Xiao Y A, Li X H, Zhang S S, Hu W H, Cao Y S, Dong M.Geographic pattern of asymmetric specialization in plant-pollinator interaction network.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2016,36(9):2544- 2551.