中国近期的步行桥设计:一种景观学方法

2016-04-11古斯塔夫·安布罗西尼,徐知兰

中国近期的步行桥设计:一种景观学方法

“他们桥梁设计的多姿多彩与雄伟壮丽毫不逊于他们在其他装饰设计方面的成就……其中一些平面呈弧线形或匍匐逶迤;还有一些则根据需要朝各个方向产生分支——有些笔直跨过河道,有些则位于河道或运河交汇处,有些呈三角形、四边形、圆形等不一而足;桥的各个转角处都设有凉亭,中央设有水池,池中饰以大喷泉或各种其他类型的喷泉。”

—— 威廉·钱伯斯,《东方园林论》,1772

众所周知,整个18世纪,在欧洲旅行家的报告中有诸多对于中国园林特色的描写,恰值当时西方美学变化发展的时期,两者交汇产生了丰富的成果,同时期还伴随着英国景观设计的革命。“但是,园林只要采取了更适宜的风格,就必定显得更为自然,而无需模仿大自然的荒蛮景象;它们看起来新颖别致却不流于造作,不同寻常又不过于夸张;园中景致不断地吸引着观赏者的注意,令人心旷神怡,不同的景色激发了人们的好奇心,并通过调动各种对比的情绪让人激动不已;这些园林设计师必定具有强大的创造力、丰富的经验和出色的判断力;它们敏于感受、手法娴熟、富于想象,并且熟稔人类所有的情感与喜好。”

今天,我们是否有可能拓展钱伯斯提出的“园林设计师”概念,把桥的设计者也涵盖在内?

本文研究的人行天桥设计涉及一些最近在中国建成的作品,桥的设计是一门与景观学的自觉意识密切相关的学科——因此,这一研究范畴能让我们暂时摆脱全球化进程与传统文化之间各类趋势呈严重两极分化的状态,在其中找到替代性设计方法的发展空间[1]。

桥在中国古典园林中的象征意义与感受作用理所当然地构成了一个必要的参照点——即设计者意识到,桥本身并不仅仅是跨越障碍的通途,同时也是综合的美学表达手段——它通过蜿蜒曲折或往复迂回的路径带领人们渐次发现一处处意外的景致。桥也常常是戏剧性效果中重要而生动的组成部分——因为它们很少呈直线形布置,而常常延续了园林小径原本左摇右摆的路线,或表现为高耸隆起的拱券,又或沿折线型在平面上展开。它们限定了人们在园中对水面的理解,又为欣赏花园中的美景提供了固定的观赏点[2]。

除了继承自古典园林的设计手法之外,我们也不妨提醒读者另一种可供参考的中国传统设计手法——即在中国许多地区发展形成的杰出的木构屋顶桥梁遗产,在湖南、湖北、贵州、广西、福建等地都有此类设计,桥的类型从建有若干座精致凉亭的所谓“风雨廊桥”,到更简单的、仅用木檩条搭建而成的桥梁等等。它们都为人们提供了带有遮蔽的空间,形成了可供会面的场所,成为具有纪念性意义的公共场所,是对农村的街道和广场空间的补充[3]。

然而,我们必须避免在今天简单地照搬过去的设计理念。似乎可以谨慎地认为,形成某一时期、某个社会文化、政治和经济状况的环境其实也表达了某种景观的理念。在这个意义上,至关重要的是需要考虑到20世纪末、多学科的交叉融合对景观的概念所产生的影响——人们由此认为,必须把景观理解为人类集体文化转型的结果,即“景观是历史上某种人们体验周围世界的方式,其周围世界由某些社会族群发展形成、且对他们具有特殊意义”,并正如地理学家丹尼斯·科斯格罗夫所写,景观是“一种由某些阶层的族群以他们想象中与自然形成的关系来定义自身身份及其所在世界的方式”[4]。

这就是为什么像玛丽·帕多瓦这样的学者会认为当代中国新建公园的设计过程表现出“混杂的现代性”,这一概念借自阿尔君·阿帕杜莱等文化社会人类学家提出的混合叙事概念——“替代的”现代性。当代中国园林设计融入传统要素的方式被认为是借鉴了不同的设计理念,并“通过象征性设计元素的形式将全球化、国家层面和本土的影响”交织在一起,由此产生了新的意义[5]。

目前,中国正密集推动的城市化进程已经拓展了各类传统设计专题的疆界,从古典园林作为自然界缩影的概念,到贯穿20世纪的大众公园的概念,直到目前新的景观概念——即人们可以生活在其中的景观,如水岸、湿地、湖畔、生态恢复后的棕地等。当今对各类土地利用方式进行转变的过程所产生的影响已经远超园林设计的单一领域——如果说住宅用地的快速增长使人们生活水平得到改善的需求变得更为迫切,各类人行步道的建设也应在中国各类以步行为主导的设计策略中获得相应的地位,以便在恢复曾被忽视的城市肌理、修复各种工业区、城市边缘地区和自然空间等区域的过程中,寻求更为人性化的尺度。

在这个意义上,研究桥如何一直保持着园林中作为感知和象征核心手段的地位,探索设计师们如何通过优美而富于戏剧性的环境促进使用者对植物、水体及其他景观要素的体验,是很有建设性的。

例如,荷兰West 8城市规划与景观设计事务所(与多义景观规划设计事务所合作)的“万桥之园”项目的象征意象即与此吻合(图1)。这个项目是2011年西安国际园艺博览会的一部分,园中蜿蜒迂回的小径引导参观者穿过茂密如森林的竹园,地面只在5处地点有所抬高。人们爬上这5座半圆拱形的桥之后,在继续沿拱桥下行之前,会惊喜地见到开阔的景观。这条小径在人们游移不定与兴高采烈的情绪之间产生的鲜明对比,有意识地象征了人生的轨迹。红色混凝土光滑的表面在一片绿意盎然中脱颖而出,凸显了桥作为表达情绪的媒介的原型作用。

在多义景观事务所的许多项目中,一些人行天桥蜿蜒着跨过水面或湿地,形成了最为密集的路径分布格局,营造了生动活泼的亲水体系。北京中关村软件园中央公园(2004年)的设计即是如此,园中相互交织的路径围绕着湖面分布,产生了连续不断的空间形态变化,并以折线的方式穿过水面( 图2)。同样,在无锡长广溪国家湿地公园(2011年)项目中,非直线形的步行道穿过几片湿地,形成了真正的探索之路,让人们能够亲身体验大自然鬼斧神工形成的各种水体形式与丰富的植被类型(图3) 。

"Not are they less various and magnificent in their bridges than in their other decorations…Some of them are upon a curve or a serpentine plan; others branching out in various directions:some straight,and some at the conflux of rivers or canals,triangular,quadrilateral,and circular,as the situation requires; with pavilions at their angles,and basons of water in their centers,adorned with Jets d'eau,and fountains of many sorts"

——W.Chambers,A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening,1772

It is widely known that descriptions of Chinese gardens features from the reports of European travellers throughout the 18th century fruitfully met an ongoing development process in Western aesthetics,accompanying the English landscaping revolution."But wherever a better style is adopted and Gardens are to be natural,without resemblance to vulgar Nature; new without affectation,and extraordinary without extravagance; where the spectator is to be amused where his attention is constantly to be kept up,his curiosity excited,and his mind agitated by a great variety of opposite passions; these Gardeners must be men of genius,experience and judgement; quick in perception,rich in expedients,fertile in imagination,and thoroughly versed in all the affections of the human mind".

Is it possible,today,to widen Chambers' term "Gardener" in order to include bridge designers?

Footbridge design is here investigated with reference to recent realizations in China,as a discipline strongly related to landscape consciousness:a field of investigation that allows to leave behind a rigid polarization among the opposite tendencies of globalization/tradition and to make room for an alternative approach[1].

The bridge's symbolic and perceptive role in Chinese historical gardens constitutes–of course–a necessary reference point:the awareness that a bridge itself shouldn't be just a tool for crossing an obstacle,but part of a comprehensive aesthetic expression that makes people gradually discover a series of unexpected sceneries,by following twisting and meandering lines.Bridges are very often vivid components of the drama:as they are rarely straight,they continue the winding concept of the path,rising to high arches or following zigzag lines.They establish how water must be perceived and provide defined viewpoints of the garden[2].

1 西安国际园艺博览会“万桥之园”/Garden of 10,000 Bridges,Xi'an International Horticulture Exhibition(图片版权/Photo courtesy:©West 8)

2 北京中关村软件园中央公园/Central Garden of Zhongguancun Software Park,Beijing

3 无锡长广溪国家湿地公园/Changguangxi Wetland Park,Wuxi(2,3图片版权/2,3 Photo courtesy:©多义景观/Atelier DYJG)

Besides the garden design legacy,it is possible to remind of another important reference in Chinese tradition:the remarkable heritage of the covered wooden bridges developed in many provinces such as Hunan,Hubei,Guizhou,Guangxi,and Fujian,from the so-called "Wind and Rain Bridges" with several exquisite pavilions to simpler woven timberframed bridges.They all offer people a shelter and a place to meet in,providing monumental public places which are complementary to village streets and squares[3].

But it is necessary to avoid the simple transplantation of concepts from the past to nowadays.It appears appropriate to carefully consider the cultural,political and economic circumstances from which a certain society,in a certain age,has expressed an idea of landscape.In this sense,it is fundamental to take into account the convergence of many disciplines,at the end of the 20th century,on the meaning of landscape:a point of view that necessarily conceives the landscape as a product of collective human transformation of nature,a "historically specific way of experiencing the world developed by,and meaningful to,certain social groups",in the words of geographer Denis Cosgrove,"a way in which certain classes of people have signified themselves and their world through their imagined relationship with nature"[4].

This is why scholars like Mary Padua look at the process of creation of new parks in contemporary China as a sphere revealing a "hybrid modernity",borrowing the conception of hybrid narrative of "alternative" modernities from social-cultural anthropologists such as Arjun Appadurai and others.The incorporation of design elements from tradition into contemporary Chinese gardens is seen as a set of references able to intertwine "global,national and local influences in the form of symbolic design elements" and produce a new meaning[5].

The ongoing intense urbanization process in China has been widening the boundaries of traditional design themes,from the concept of the classical garden–as a microcosm of the natural world–through the 20th-century's public park concept,to new landscapes to be lived,such as riverbanks,wetlands,lakeshores,recovered brownfields etc.Today territorial transformations oblige designers to go far beyond the unique field of garden design:if the quick growing of settlements makes even more urgent the need to improve living conditions,the construction of new footbridges should gain a relevant status in pedestrian-oriented strategies in China,in search for a more human scale in the recovery processes for neglected urban fabrics,industrial areas,marginal zones,and natural spaces.

In this sense it would be productive to investigate how bridges quite often keep on playing a central role as perceptive and iconic tools,exploring the way many designers drive users' experience of vegetation,of water and of the various elements through scenic and dynamic settings.

This is a status to which refers,for instance,the symbolic image of the "Garden of 10,000 bridges"

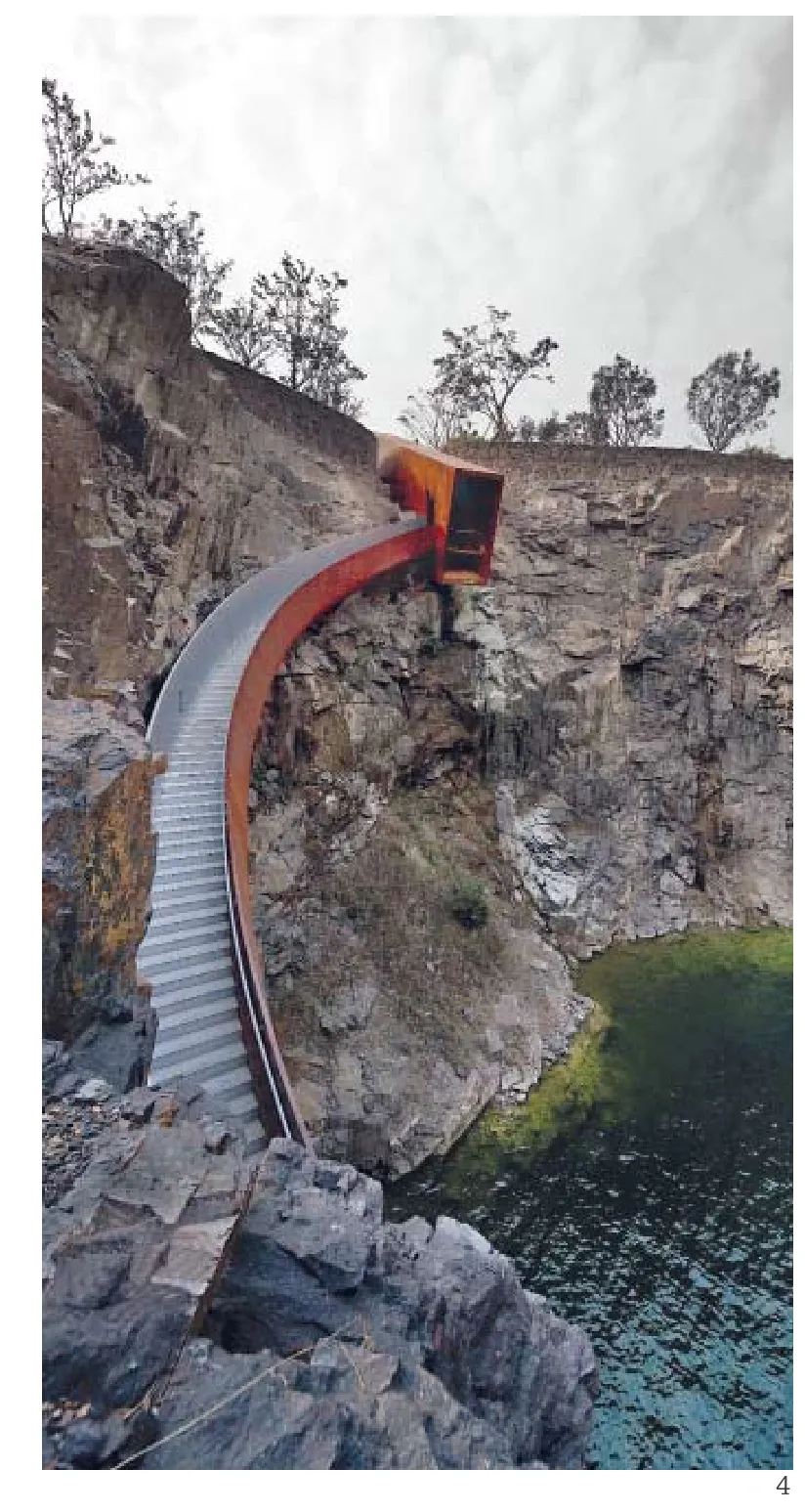

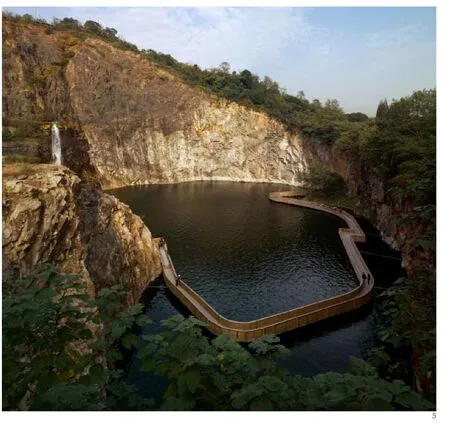

当一座废弃工厂需要转变为园林景观时,如何进入和如何穿越场地永远都是设计策略的关键所在。由北京清华同衡规划设计研究院有限公司和清华大学建筑学院(建筑师朱育帆、姚玉君、孟凡玉)设计的上海辰山植物园的矿坑花园就是一个令人印象颇为深刻的案例。包裹在锈蚀钢板中的陡峭台阶作为顶部花园和深水池之间的过渡,通过一个双重桥梁体系带领游客探索这座旧矿坑。人们顺着曲线形的步行桥攀缘而下,途经崎岖的崖壁,桥两侧的钢板一面锈蚀,另一面则光洁如新(图4);然后,他们陡然来到一座岩洞下方,发现自己正站在一座浮桥上,曲折的步道则继续引领人们前进,变化的景象令人叹为观止(图5)。材料或坚硬或柔软的质地形成了鲜明的对比,更强化了人们在经过不同路段时的情绪感受——自岩石上悬挑下来的锈蚀金属桥强调了向下“跳跃”的动态;而浮桥上木质甲板与扶手表面的光滑质感,则可让人轻松平和地欣赏周围的景色。

4 上海辰山植物园矿坑花园/Quarry Garden in Shanghai Botanical Garden

5 上海辰山植物园矿坑花园木栈桥/Wooden Floating Bridge,Quarry Garden in Shanghai Botanical Garden(4,5摄影/Photos:陈尧/CHEN Yao)

在许多案例中,对水域的改造将传统的园林范畴拓展到了地景的尺度——鉴于涉及到大面积地恢复退化的自然区域、逐渐荒废的工业区、修复住宅区的边界以及基础设施,这不仅是规模上的变化,也是设计意义的变化。

土人景观事务所设计的六盘水明湖湿地公园项目(2013年)拓宽了那里曾经开凿过隧道的河堤,由此形成了流域盆地。梯田式的池塘、小岛和林木线都被蜿蜒的步行系统衔接在一起——部分人行步道被设计为混凝土立柱的高架桥,在水面上形成了弯曲而细长的道路(图6)。

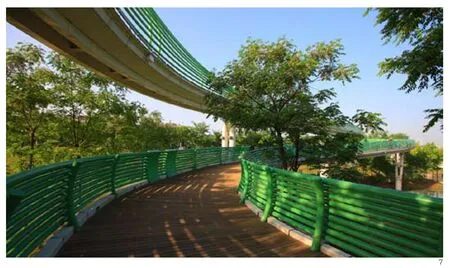

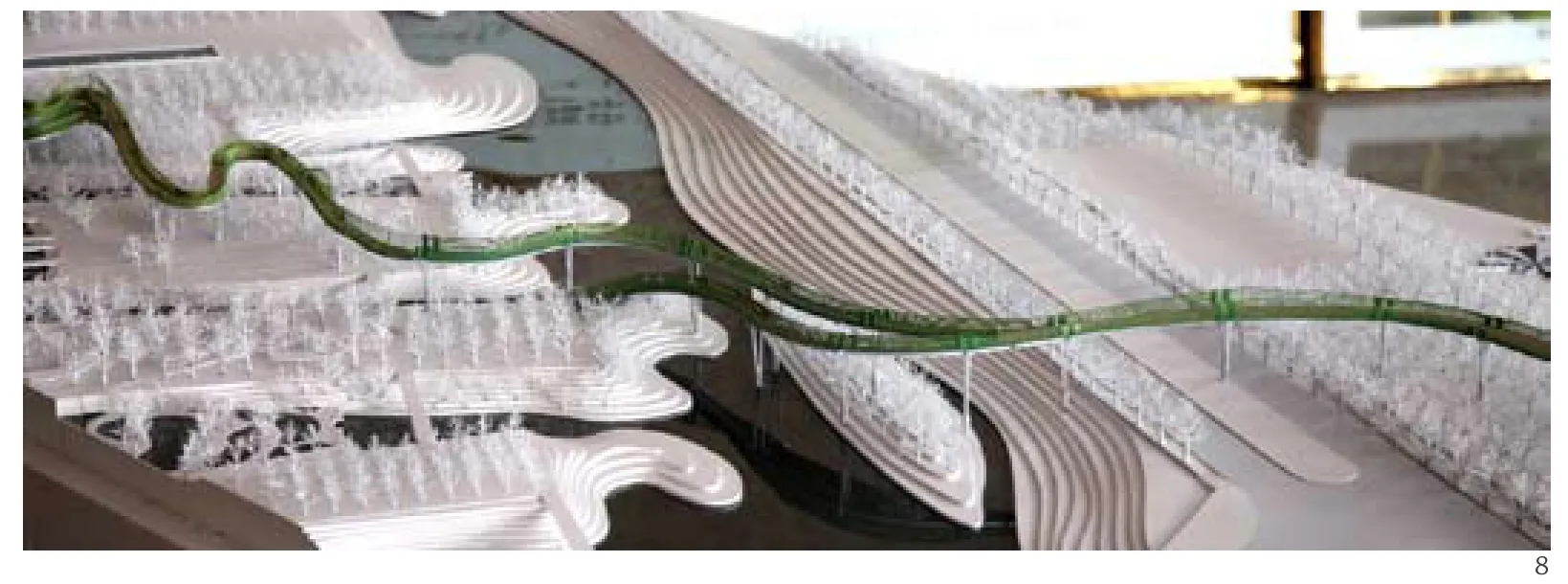

土人景观事务所在徐州睢宁流云水袖桥(2010年)的设计中也采用了类似的手法(图7,8)。它远看犹如一条碧绿的飘带,从地面上缓慢地升起,在整个景观范围内曲折蜿蜒了几百米,其间越过了一条宽阔的快速道路和若干河道。这条弯曲的步行道共长869m,另有4条平行的坡道与之衔接,可通往公园内的其他几处地点。步道曲折的线条强调了这个景观的有机特征,并形成了一种动态感——它是设计师之所以借鉴“中国京剧中舞动的水袖所形成的光影,以其一气呵成的效果和流动的曲线形状成了天然轮廓”的原因。各种细部的尺度似乎也恰如其分地呼应了项目本身的大尺度——扶手并未采用纤细的形状,而表现出厚重与坚实的形态——也让这座桥从远处就能为人们所见,也吸引了沿周边道路快速经过的游客的注意力。夜晚的人工照明展示系统则更突出了这种效果。这座步行桥不仅能供游客快速方便地抵达公园,其自身也成为公园的“主干”——既为人们提供了丰富多变的观景角度,成为公园场地的向导,也构成了某种“地形上的点睛之笔”[6]。

在更小的尺度上,在日照的项目i中,一条条曲线型的白色钢管形成了蜿蜒的桥身,衔接了城市与水岸线,它们看似是从河畔的植被中生长出来的。这座长达2km的步行桥坐落在日照山海天海滨的南侧,毗邻鲁南海滨国家森林公园,是一个大型再开发项目的一部分(图9)。该项目涉及各类基础设施和休闲区域,由HHDFUN事务所(王振飞,王鹿鸣)完成(2012年)。整个项目共同的设计思路是利用波浪起伏的有机形态、通过参数化的设计手段进行图纸表达。桥身有两条主结构的钢管以非对称的曲线形态从市区一侧延伸出来,在步道中点的最高处汇合,之后又展开为4个分支,朝海滨森林公园的方向延伸下去;竖琴般的钢索构成了透明而线条流畅的外立面。稍有弯曲的步行道在中部收窄,曲线形的钢管则形成了动感强烈的元素,它们在融入周围景观的同时,吸引着游客积极地感受这里的自然环境。

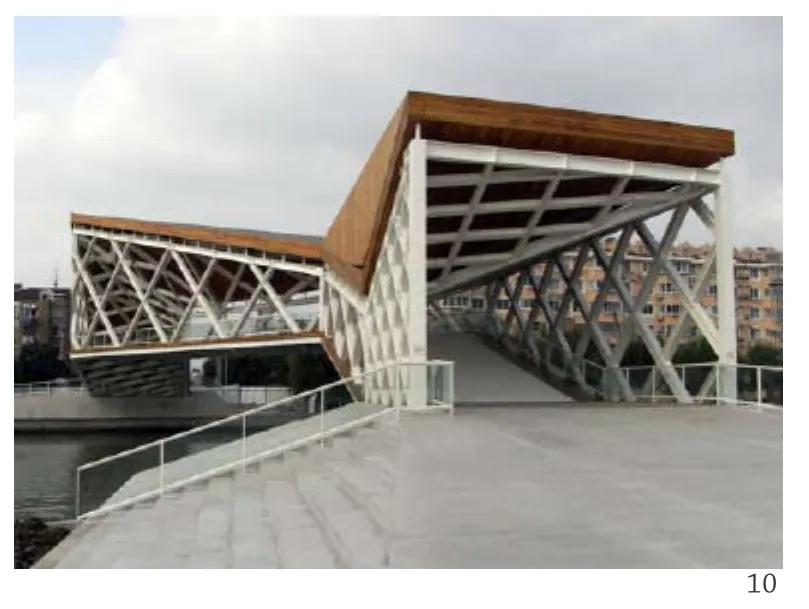

在一些案例中,传统的非直线形步道理念则已与某些结构形式结合在一起。在上海青浦的项目中ii,文筑国际的设计总监白德龙设计了一座折线形的步行桥(2008年),形成的带有顶棚的步道穿过了颇为迂回的淀浦河(图10)。桥身曲折的结构由3部分构成——其中两段较短的桥身在平面上与河岸相垂直,设有台阶,坡度较缓;另一段桥身则在平面上有些偏转,平整的甲板在水面上形成了带有遮蔽的广场空间。由双向弯曲产生的扭力通过三维立体结构来支承——这是一种特别的桁架,其形状与桥梁本身不对称弯折的动态趋势相吻合。结构体系则project by West 8 office(in partnership with Atelier DYJG)for the 2011 Xi'an International Horticulture Exhibition(Fig.1).A circuitous and winding trail leads the visitors though a dense,forest-like bamboo garden,rising up only at five points:five semi-circular bridges let people peak out over the vegetation and have a surprising wider view before climbing down again.The path is intended to represent a sort of trajectory of human life,marked by contrast between uncertainty and elation.The red smooth concrete surface brightly sticks out from the greenery,highlighting the archetype of the bridge as a medium for emotion.

In many projects of Atelier DYJG,some winding walkways rising over the water or wetlands constitute the most intense segments of the path layout,providing a vivid way to get in touch with the water system.This is the case of the Central Garden of Zhongguancun Software Park in Beijing(2004),where the interweaving paths create continuous spatial variations around a lake and zigzagging over the water(Fig.2).Also in Changguangxi Wetland Park in Wuxi(2011)the bending path establishes a real discovery trail across the wetlands,in order to let people experience the natural succession of diversified water and vegetation features(Fig.3).

When an abandoned worksite claims to be turned into a garden,the way to get in and to walk through it remains a key role in the design strategy.The Quarry Garden in Shanghai Botanical Garden(2009),designed by Beijing Tsinghua Tongheng Urban Planning and Design Institute Co.Ltd.+ School of Architecture of Tsinghua University(arch.Zhu Yufan,Yao Yujun,Meng Fanyu),is an impressive example.A steep stairway encapsulated in a rusty steel box acts as a threshold between the top gardens and the deep pool,taking visitors to discover the former quarry through a double bridge system.People climb down,dramatically brushing against the rocky hillside,along a curved bridge,which has one side made of rusted iron and the other of burnished steel(Fig.4); then,after having turned abruptly under a stone grotto,they find themselves on a floating bridge,eye-catching continuously changing views from the meandering path(Fig.5).The contrast among hard and soft materials strengthens the emotional feeling of the different phases of the route:rust metal suspended from the rocks is meant to highlight the "jump" down,while smooth wooden surfaces for the deck and the railings of the floating path are designed for peaceful appreciation of the landscape around.

In many cases,watersheds regeneration items widen the traditional scale of the garden to a landscape scale:not just a dimensional shift,but also a shift in meaning,whereas large areas to be recovered involve degraded natural zones as well as obsolescent industries,settlement borders and infrastructures.

In Liupanshui Minghu Wetland Park,designed by landscape office Turenscape(2013),the riverbed,previously channelled,has been re-enlarged and a drainage basin was created.Terraced pools,islands and tree lines are interwoven by a system of winding paths:some of them form elevated walkways,standing on concrete pillars,and create long twisting routes above the water(Fig.6).

6 六盘水明湖湿地公园/Liupanshui Minghu Wetland Park

Turenscape has put in place a similar strategy in the design of Long Sleeve Skywalk in Suining County,Xuzhou City(2010,fig.7,8).Seen from a distance it appears as a long green ribbon,which gently rises from the ground and sinuously spreads over the landscape for many hundreds of meters over-passing a large fast road and several watercourses:it's a meandering walking path with a total length of 869m,reached by other four almost parallel long ramps connecting some points of the park.The sinuous line of the path stresses the organic character of the landscape,providing a sense of movement:that's why the designers refer to the memory of the "dancing shadows of long sleeves of Chinese operas,where seamless and flowing curves follow natural contours".The scale of the details–not thin railing elements,but thick and solid ones–seems to appropriately respond to the large scale of the project,allowing it to be seen even from a long distance,and to be caught in the eye by the fast traveller along the infrastructure too; this is accentuated at night by the artificial light display system.The walkway is not only an easy and safe way to reach the park,but it constitutes by itself the park's "backbone" as well:it offers a continuous change of viewpoints and gives orientation to the place,acting as a sort of "topographic eye"[6].

At a smaller scale,in Rizhao,several curved white steel tubes seem to grow out from the riverbank vegetation to shape a sinuous bridge that connects the city with the shoreline.Located in the southern part of the 2km-long Shanhaitian beach bordering the Lunan National Forest Park,the bridge is a part of a wide redevelopment project,concerning facilities and recreational areas,by HHD_FUN Architects(2012,fig.9).The common thread of the overall project is the use of waving organic forms,drawn through parametric design techniques.Two main steel tubes rise from the city's side,bend asymmetrically to converge at their highest point in the middle of the path,and then由外形规整的工字钢形成的方形网格倾斜45°构成,并根据剪力要求在需要的局部加密。

7 徐州睢宁流云水袖桥/Long Sleeve Skywalk,Suining,Xuzhou

8 徐州睢宁流云水袖桥模型/Model of Long Sleeve Skywalk (6-8图片版权/6-8 Photo courtesy:©土人设计/Turenscape)

9 日照步行观景桥/Rizhao Footbridge(图片版权/Photo courtesy:©HHDFUN)

在这里,我们有可能找到一种对各类借鉴自传统的独特要素进行现代式综合的方法——一方面,桥作为媒介,提供了以非直线形路径穿越水面的体验,形成了步移景易的效果;另一方面,桥的形象又为人们提供了一处场所,用设计师的话来说,即一座“水上的房间”。

最后一个重要的议题是如何与一些植根于本土的技术手段进行互动。

在这方面,由马克·曼朗建筑师事务所在扬州设计的柳叶步行桥实践项目非常有意义(图11)。这座桥位于旧城中心的西南角,其外观是一个令人炫目的白色金属符号,横跨古老的大运河;尽管在远处看,它可能让人联想起中国传统的石拱桥,但从技术角度看,两者却有极大的差异——这座桥采用了剖面不断变化的箱形梁结构。利用现有高超的金属板加工工艺进行设计的能力让设计师能够避免来自外部的预设技术,并将本土的技艺作为珍贵的技术手段和认同感的来源发扬光大。

无止桥慈善基金会也在这方面进行着一些值得关注的活动。这个来自香港的基金会,在国家住房和城乡建设部的支持下,在中国的偏远地区和不发达地区组织了许多桥梁(自2007年起建成了30座)和基础设施的建设工程。这些项目通常都必须面对一些挑战,包括来自具体场地条件限制(倾斜的水岸,有些是交通工具或电力设施无法到达的地方)和创造力匮乏的技术手段。

由奥雅纳工程咨询(上海)有限公司和无止桥基金会共同合作完成的云南省咪霞村无止桥iii(2013年)就是一个杰出的案例(图12)。这座桥身的每一个单独构件都不能超过一定的重量,否则无法由人工运到山上。一些用当地采集的石块填充的篾筐被用来作为两岸基础框架的重量平衡构件。径向和横向的镀锌钢梁构成的结构十分坚固,钢梁之间用手工拧牢的螺丝螺帽和螺栓连接固定。桥面甲板是透空的网格,扶手则是一些半圆形的条状构件。在现场以外通过测试之后,这些构件被运往当地,由50位志愿者在12天里建造完成。当时还利用了当地的竹加工技术——现场的临时脚手架体系就由竹框架绑钢筋、锚件、皮带轮和绳索建成。这个项目清楚地表明如何能够有效地利用高水平的专业知识理解和建造易于组装的预制结构,以适应特殊的当地条件并同时在施工中利用当地技术。

作为总结,通过不同案例的比较研究可以得出一些重要结论。其中一项关键的议题就是以创造性的方式借鉴传统、并通过当代形式满足当代社会需求的能力。本文案例涉及的设计师都避免了以肤浅或陈词滥调的符号为基础对过去经验进行转译(如类似塔形或龙形的样式),并通过推动主流的设计态度转向以用户感知体验为主导,重新阐释了传统观念中关于移动的概念——上文分析过的人行步道都能够和谐融入周围景观,并同时提供了活泼的手段供人们理解景观。不仅如此,在更微妙的意义上,对一种文化的转译进行反思也意味着文化的外延得到拓展,由此将技术也纳入其中——也就是有可能向本土技艺进行学习并与之互动——这种策略已在一些案例中取得了成功,并将研究对象拓展至富有成效的范围。(致谢:笔者要特别感谢克里斯蒂亚妮·M·埃尔对于中国步行桥的结构与造型问题的探讨。)

参考文献/References:

[1] Rowe,P.G.,Kuan S.(2002),Architectural Encounters with Essence and Form in Modern China,Cambridge,Mass:MIT Press,2004.

[2] Chen,L.,Yu,S.(1986),The Garden Art of China,Portland:Timber Press; Tang,H.C.(1991),Philosophical Basis For Chinese Bridge Aesthetics,in Transportation Research Board,Bridge Aesthetics Around the World,Washington:Library of Congress; Rinaldi,B.M.(2011),The Chinese Garden:Garden Types for Contemporary Landscape Architecture,Basel:Birkhäuser.

[3] Knapp,R.G.(2008),Chinese Bridges:Living Architecture from China's Past,Tuttle:Rutland.

[4] Cosgrove,D.E.(1984),Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape,University of Wisconsin Press.

[5] Appadurai,A.(1996),Modernity at Large:Cultural Dimensions of Globalization,Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press; Padua,M.G.(2007),Hybrid Modernity:Framing the Public Park in Post-Mao China,in Negotiating Landscape,CELA.

[6] Saunders,W.S.(ed.)(2012),Designed Ecologies.The Landscape Architecture of Konjian Yu,Basel:Birkhäuser.

译注:

i 指日照步行景观桥。

ii 指上海青浦步行桥。

iii 具体位置在云南省红河州绿春县平河乡咪霞村。divide themselves into four lines spreading down towards the beach park; harp-like steel strings create a smooth,transparent exterior façade.The combination of the slightly meandering path,narrowing in the middle,and the curved steel tubes generates a strong dynamic feature able to fit in the landscape and in the meantime to drive the users' attention to a vivid perception of nature.

10 上海青浦步行桥/Qingpu Footbridge(图片版权/Photo courtesy:©文筑国际/CA-Design)

11 扬州柳叶桥/Liu Ye Footbridge,Yangzhou(摄影/Photo:Agence Mimram Paris)

12 云南省咪霞村步行桥/Mixia Village Footbridge,Yunnan Province(图片版权/Photo courtesy:©Arup)

In some cases,the traditional concept of bending walk has been combined with specific structural form.In Qingpu,Pedro Pablo Arroyo Alba of CA Design envisaged the creation of a zigzag bridge,hosting a covered path to cross somewhat obliquely the Dianpu River(2008,fig.10).Three segments give form to the bent structure:two short ones,orthogonal to the riverbanks in plan,provide gently stepped ramps,while the longer segment,oblique in plan,features a flat deck able to perform as a sort of covered square flying over the water.The torsion induced by the double bend is supported by a three-dimensional structure:a unique steel truss girder,shaped in accordance to the asymmetric diagram of bending momentum.It is made of regularly dimensioned H steel set as a 45°-rotated squared frame,denser when necessary according to the diagram of shear stress.

Here it is possible to find a modern synthesis of distinct characters borrowed from tradition:on the one hand,the idea of a bridge as a medium to provide a non-straight experience of crossing the water,offering changing viewpoints over the landscape; on the other hand,the image of a bridge offering people a place,in the designers' words,"a room over the water".

Finally,one significant topic is the interaction with specific locally-rooted technological skills.

In this regard,the Liu Ye Footbridge in Yangzhou designed by Marc Mimram(2010)is a meaningful realization(Fig.11).The bridge appears as a glowing white metallic sign spanning across the Old Grand Canal,on the West-South border of the historic city centre; although from the distance it might recall the image of traditional Chinese arch-type bridges,it is radically different from the technological point of view:a box girder with a continuously changing section.The capacity to take advantage of the existing high craftsmanship in working sheet metal allowed to avoid pre-defined technologies imposed from abroad,thus enhancing local savoir faire as a precious technical and identity resource.

A noteworthy activity in this respect is being carried out by Wu Zhi Qiao(Bridge to China)Charitable Foundation,a Hong Kong charity that has organised the building of many bridges(more than 30 completed from 2007)and village facilities in remote rural and underprivileged areas of China,with the support of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development.Very often the projects need to confront with challenging specific site conditions(steep banks,sometimes no vehicle access or no electricity available onsite)and low innovative technological skills.

The bridge built in Mixia Village,Yunnan Province(2012),by a collaboration between Arup and Wu Zhi Qiao Foudation,is a significant example(Fig.12).No single component could have an excessive weight as it had to be hand-carried along the mountain path; some gabions,made of wire cages filled with locally sourced stones,were used to counterweight the base frame on each bank.Galvanised steel longitudinal beams and transversal components form a rigid structure,connected by hand with nuts and bolts; the decking is an open mesh,and the railing consists of a series of semicircular bars.After a previous offsite testing,the components were transported on site and built up in 12 days by a team of about 50 volunteers,taking advantage of the local skills in bamboo working as well:a temporary suspension cable system was built onsite,using bamboo frames holding steel wires,anchors,pulleys and ropes.The project clearly shows how a high level technical expertise can be usefully exploited to conceive and produce easy-to-assemble prefabricated structures,in order to fit with specific site conditions and in the meantime to make good use of local know-how for the construction.

In conclusion,significant items appear from the comparison of the different case studies.One of the key topics is the capability to make reference to tradition in an innovative way,and to fulfil contemporary needs through contemporary forms.The designers avoided an interpretation of the past based on trivial or clichéd icons(e.g.pagoda-like,dragon-like forms)and interpreted the traditional idea of movement by driving the main design attitude toward the perceptive experience of the users:the footbridges analysed above fit harmoniously in the landscape,becoming a part of it,and in the meantime offer a vivid way to perceive it.Furthermore,the reflection on interpretation of a culture in a more subtle way has meant to refer to a wider meaning of culture,thus including technical features as well:the possibility to learn from,and interact with,local know-how has been in some cases a successful strategy that opens the way to a fruitful field of investigation.(A special thanks to Christiane M.Herr for discussing structure and shape matters in Chinese footbridges.)

摘要:景观意识是中国近期步行桥设计中的一个普遍特征,并以恢复水岸、湿地、湖畔、棕地生态以及城市肌理为目标。以创造性的方式借鉴传统元素,借助富有活力的优美环境、通过与地方特征和技艺的互动,调动使用者的知觉体验,一同构成了当今中国步行桥设计的主要特点。

Recent Footbridge Design in China:A Landscape Approach

古斯塔夫·安布罗西尼/Gustavo Ambrosini徐知兰 译/Translated by XU Zhilan

Abstract:the landscape consciousness is investigated as one of the common features in many new footbridges recently built in China,aimed at recovering riverbanks,wetlands,lakeshores,brownfields,as well as urban fabrics.The incorporation of elements from tradition in an innovative way,the capacity to drive the perceptive experience of the users through scenic and dynamic settings and the interaction with local identities and know-how constitute some of the main items.

关键词:步行桥,中国园林,传统,创新

Keywords:footbridge,Chinese garden,tradition,innovation

收稿日期:2016-02-23

作者单位:都灵理工大学