Diet and Prey Selection of the Invasive American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) in Southwestern China

2015-12-13XuanLIUYuLUOJiaxinCHENYisongGUOChangmingBAIandYimingLI

Xuan LIU, Yu LUO, Jiaxin CHEN, Yisong GUO, Changming BAI,and Yiming LI*

1Key Laboratory of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

2School of Life Science, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang 550001, China

3School of Life Science, South China Normal University, Guangzhou 510631, China

4Department of Ecology, Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, Yunyang Teachers’ College, Danjiangkou 442000, China

5Key Laboratory of Sustainable Development of Marine Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

Diet and Prey Selection of the Invasive American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) in Southwestern China

Xuan LIU1, Yu LUO2, Jiaxin CHEN3, Yisong GUO4, Changming BAI1,5and Yiming LI1*

1Key Laboratory of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

2School of Life Science, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang 550001, China

3School of Life Science, South China Normal University, Guangzhou 510631, China

4Department of Ecology, Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, Yunyang Teachers’ College, Danjiangkou 442000, China

5Key Laboratory of Sustainable Development of Marine Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China

Invasive predators have been widely regarded as one of the principle drivers of the global decline of amphibians, which are among the most threatened vertebrate taxon on Earth. The American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) is identifi ed as one of the most successful vertebrate invaders and has caused the decline or extinction of some native amphibians in many regions and countries including China. Based on fi eld surveys and stomach content analyses, we examined the diet composition of the invasive bullfrog for the fi rst time in two invaded populations in Yunnan Province, southwestern China, a region of global conservation priority, during the breeding season from 2008 to 2014. Additionally, we conducted the first quantitative study on the prey selection of this global invader among their invaded ranges after controlling for the local anuran assemblage and other aquatic preys in the environment. Our results showed that the range of food items in the stomachs of bullfrogs spanned more than 30 species belonging to ten taxonomic classes. Both of post-metamorphosis individuals and juveniles preyed upon native frogs, independent of the bullfrog’s body size and mouth width. Importantly, Jacobs’ selection index showed a bullfrog preference for the Yunnan pond frog (Babina pleuraden), one native endemic anuran with population decline, in terms of both food volume and occurrence. We therefore provided direct evidence on the predation impact of the invasive bullfrog on an endemic anuran and urged further efforts to prevent the dispersal of this invader into more fragile habitats to reduce their negative impacts on native amphibians.

Amphibian decline, American bullfrog, diet preferences, invasive species, Babina pleuraden, predation

1. Introduction

Biological invasion is a major cause of biotic homogenization, which is often mentioned as the process of the replacement of native species by widespread exotic species (Olden and Rooney, 2006). Amphibians stand out among the casualties of such homogenization and are now considered the most threatened vertebrate group on the planet (Stuart et al., 2004), and invasive predators are widely known as a pernicious driver of global amphibian decline (Kats and Ferrer, 2003). Among them, the American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus; hereafter referred to as the bullfrog) has long been of conservation concern due to its wide non-native distribution over 50 countries and regions (Ficetola et al., 2007; Kraus, 2009), rapid adaptability to novel environments (Li et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2010), rapid population growth rate (Govindarajulu et al., 2005), and high range of expansion (Austin et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2014). The bullfrog is also an important vector of the chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), anemerging disease implicated in the global amphibians decline (Garner et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2013b). Except for the disease transmission, this species can have direct negative effects on native fauna through competition (Kiesecker et al., 2001; Kupferberg, 1997), breeding interference (D’Amore et al., 2006; Pearl et al., 2005), but most commonly its unspecialized predation on natives (Jancowski and Orchard, 2013). Many efforts have been made to explore the bullfrog predation on native communities around the world, with results showing that bullfrogs can predate a large number of prey species, including insects, crustaceans, and large vertebrates such as fishes, birds, reptiles, and amphibians (e.g., Hirai, 2004; Hothem et al., 2009; Krupa, 2002; Lopez-Flores and Vilella, 2003; Silva et al., 2011; Werner et al., 1995; Wu et al., 2005). However, these studies mainly focused on diet compositions through analyses on stomach contents, or examined prey selection of bullfrogs only on native anuran assemblage (Boelter et al., 2012; Pearl et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005), and to the best of our knowledge, their predation preferences after controlling for the environmental anuran and other aquatic prey availability are unfortunately unknown. Indeed, quantifying the predation preference of introduced bullfrogs is important for estimating their predatory impacts on native amphibians and for understanding the mechanism of native biotic homogenization by this invader.

The bullfrog was first introduced into China for aquaculture in the 1960s, and it then expanded across the country in the 1980s (Liu et al., 2010). Currently, the bullfrog has successfully established feral populations in many provinces from eastern to western China (Li and Xie, 2004; Li et al., 2006; Liu and Li, 2009). In the Zhoushan Archipelago of China, the density of postmetamorphosis bullfrogs showed a negative relationship with the native frog density and species richness (Li et al., 2011). The bullfrog has also successfully invaded the southwestern China Plateau (Liu and Li, 2009; Liu et al., 2013a; Liu et al., 2012), an area that is a global biodiversity conservation hotspot (Myers et al., 2000) and is among the areas with the largest number of endemic amphibian species in China (Xie et al., 2007). However, direct evidence for bullfrog predation on endemic amphibians is still lacking. The bullfrog also exhibits geographical variations in body size and sexual size dimorphism in response to different elevations (Liu et al., 2010), thus providing opportunities to investigate geographical variations in their diet habits and to evaluate differences in their predation impacts on native fauna. There are three main objectives in the present study: (1) to describe the bullfrog diet composition in two invaded communities in Yunnan Province, southwestern China; (2) to investigate variations in the bullfrog diet among individuals of different body size, sex, and populations; and (3) to explore the bullfrog’s feeding preference on native aquatic communities and to evaluate the degree of the predation impact on endemic amphibians.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study area Our study was conducted in Yunnan Province situated in the plateau region of southwestern China, where there is a complex climate including tropical, subtropical, temperate, and boreal climates (Yang et al., 1991). We focused on intensive samplings at two sites, one with a low altitude (Shiping at an elevation of 1500 m, 23°42' N 102°28' E) and one with a high altitude (Caohai, Lugu Lake at an elevation of 2,692 m, 27°42' N 100°51' E), on the border between Ninglang County of Yunnan Province and Yanyuan County of Sichuan Province (Figure 1). The bullfrog has established feral populations in these two sites, which descended from a single source population introduced from Cuba in the 1980s (Liu et al., 2010). The Shiping site is located at Yilong Lake, which is a large freshwater lake in Yunnan Province. Caohai is a grassy plateau wetland that is part of Lugu Lake, the largest lake in Yunnan Province, a natural lake in the Hengduan Mountain System and set in the subalpine zone in the southern Hengduan Mountains as a pine-covered eco-region. Except for the bullfrog, historical literatures also recorded the distribution ofseveral other native amphibian species including the Yunnan Pond Frog (Babina pleuraden), the Largewebbed Bell Toad (Bombina maxima), the Yunnan Odorous Frog (Odorrana andersonii) and the Vocal-Sacless Spiny Frog (Paa liui) in the study area (Fei et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1991). However, we did not detect the occurrence of O. andersonii and P. liui but only B. pleuraden and B. maxima during our field surveys in recent years (Liu and Li, 2009; Liu et al., 2013a; Liu et al., 2012).

2.2 Bullfrog diet habits We sampled both adult and juvenile bullfrogs during the breeding season from the year 2008 to 2014 by hand, dip-netting, and electrofi shing with the aid of an electronic torch at night (19:00-23:00). The bullfrogs were captured along line transects that were 2 m wide (with 1 m in the water and the other half on the bank) and 20 m long along the accessible shorelines. All captured frogs were taken indoors for further analysis. We measured snout to vent length (SVL; to the nearest 0.02 mm) and mouth width with a vernier caliper and body mass (to the nearest 0.1 g) with an electronic balance of each live specimens. We identified the sex and ontogenetic stage of each specimen according to the development of secondary sexual characters. Males were identifi ed based on the presence of nuptial pads and yellow pigments on the throat and chest. Frogs lacking male characteristics were classifi ed as females and those with SVL lower than the minimum size of male bullfrog were considered as juveniles (Wang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2005). We performed a ventral incision on the alimentary canal of each anaesthetized specimen with ethyl acetate, and the stomach contents were immediately removed to a Petri dish and preserved in 70% alcohol (Jancowski and Orchard, 2013; Leivas et al., 2012; Silva et al., 2011). The contents of each stomach were identifi ed to the lowest possible taxon (usually family) with the aid of a magnifi er (8 ×), and the length and width (to the nearest 0.02 mm) and body mass (to the nearest 0.1 g) of each prey item were measured.

2.3 Prey selection To quantify the feeding preference of the bullfrog on native amphibians, we studied bullfrog prey selection focused on aquatic vertebrates including amphibians and fishes in the Caohai population. These prey types were studied because they comprised the major aquatic vertebrate prey based on our stomach content analyses in Caohai (Table 1). In the case of native anurans, we included the B. pleuraden and the B. maxima, which were the two dominant amphibian endemic species in Caohai based on the field survey (Liu and Li, 2009). We treated tadpoles and juveniles together for the data analyses. For fishes, we focused on the Cypriniformes species that appeared in the bullfrog diet. The Caohai population was chosen for the prey selection study because the aquatic habitat at this site was accessible to the investigators, and thus tadpoles, fishes, frogs and toads could be collected by nets and electrofishing. The frogs and toads were sampled along a total of 11 line transects where the bullfrogs were captured. Fish and tadpole sampling was conducted using nets located parallel to the land transects, and the sampling of each individual per amphibians and freshwater species was conducted simultaneously by two researchers during 1 hour (Blanco-Garrido et al., 2008). The availability/ abundance of each prey species was calculated by both the number (individuals/m) and biomass (g/m), and then we calculated the proportion of each prey species in the environment for further Jacobs’ selection index estimation.

2.4 Data analyses We quantifi ed the prey composition of each stomach by estimating the number of prey individuals, the composition of prey species, prey biomass, and prey volume which was approximated as an ellipsoid using the formula: Volume = 4/3π(length/2)×(Width/2)2(Magnusson et al., 2003). Those accidental fragments of plants and minerals were not included in the further data analyses. We determined the relative frequency of the number of individuals, biomass and volume of each prey category in the total stomach content of bullfrogs. Considering that there was a strong positive correlation between the body size and mouth width of the bullfrog (Pearson correlation r = 0.937, P < 0.001), we performed Pearson correlation analyses and only reported the results involving number of prey individuals, biomass, volume and body size of the bullfrogs (ln-transformed). We conducted Kruskal-Wallis test to explore the difference in prey composition among males, females and juveniles. We used ANCOVA to evaluate variations in prey composition, biomass and volume between two populations after controlling for the effects of bullfrog body size which might influence the results.

To quantify the bullfrogs’ feeding preference or avoidance, we used Jacobs’ selection index, calculated as: D = (r - p)/(r + p - 2rp); where r is the proportion of a prey category in the diet and p is the proportion of the prey category in the environment (Hayward et al., 2006; Jacobs, 1974). The index has a range from -1 to +1, with -1 being maximum avoidance, 0 indicating random selection and +1 indicating maximum preference.We used this selection index because it was suggested independently of prey sizes and the relative abundances of prey items in the environment (Jacobs, 1974). The Jacobs’ index was calculated both at the level of individuals and biomass for each prey category in each of the 11 sampling transects. We firstly examined whether bullfrogs predated each prey category randomly against the null hypothesis of a mean Jacobs’ index equal to zero using t-tests. We then explored difference in mean Jacobs’ indexes among prey species using Kruskal-Wallis test, and performed Mann-Whitney U tests for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed in R (Version 2.15.1, R Development Core Team, 2012).

3. Results

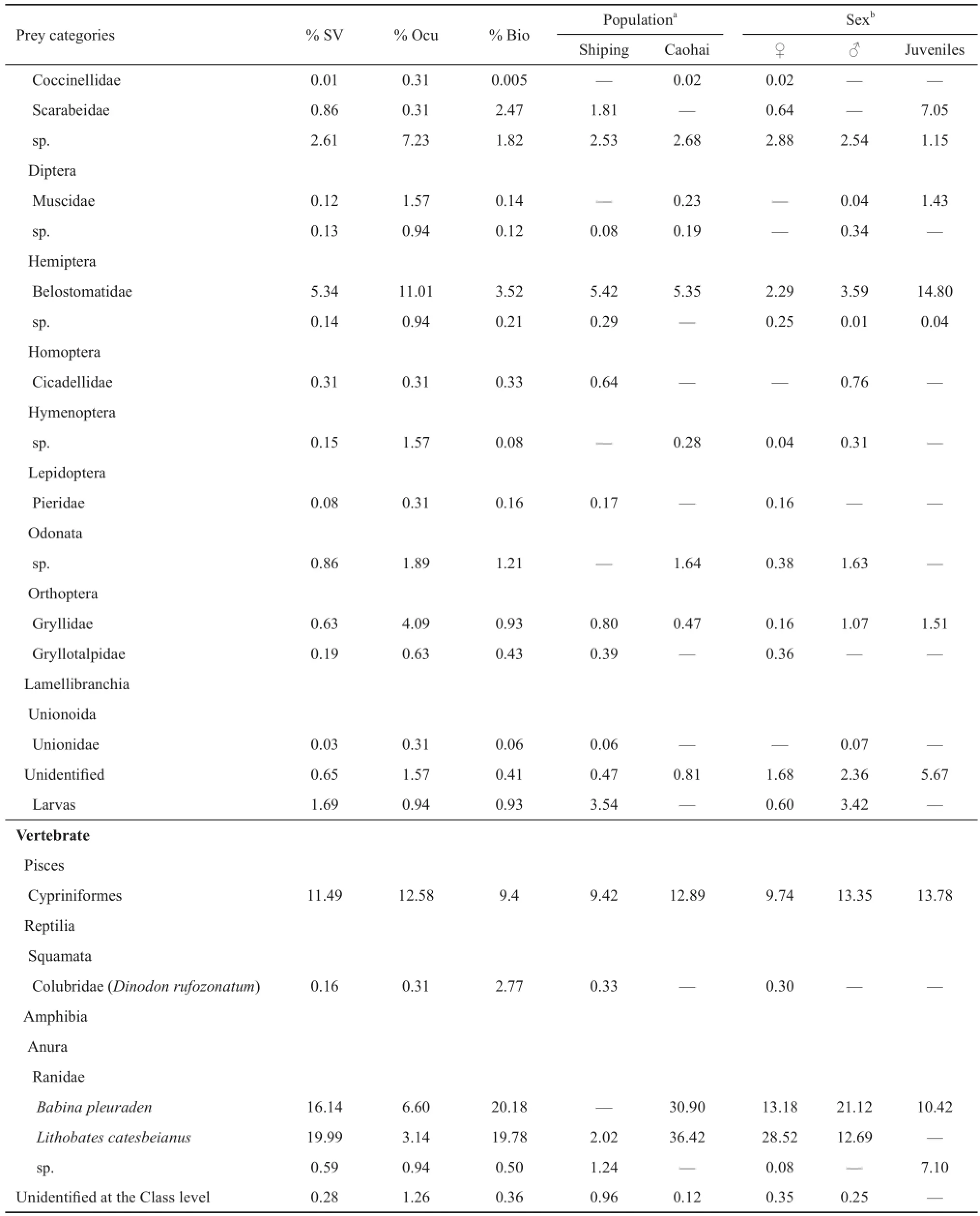

3.1 Diet compositions of bullfrogs A total of 214 bullfrogs (Shiping: n = 101; 40 males, 37 females, 24 juveniles; Caohai: n = 113; 47 males, 45 females, 21 juveniles) were sampled, and a proportion of 18.2% (39 individuals) were found with empty stomachs. We recovered 34 prey items in the two populations with 27 prey items found in the Shiping population and 16 prey items in the Caohai population. When combining all insect items together, the stomach content analysis showed that insects were the most commonly observed food (proportion of occurrence:37.4%), with the highest prey species diversity (19 species) (Table 1). The other relatively frequent categories included Cypriniformes fishes (12.6%), Palaemonidae crustaceans (11.0%), and Ranidae (10.7%) (Table 1). Cannibalism of bullfrogs (juveniles and tadpoles) and B. pleuraden made up approximately 19.9% and 16.1% in terms of volume, respectively, followed by Cambaridae (crayfish; Procambarus clarkii) (15.9%). In terms of biomass, B. pleuraden and bullfrog cannibalism represented 20.2% and 19.8%, respectively, followed by Potamidae crabs (9.9%) and Cypriniformes fishes (9.4%) (Table 1). Other prey categories had relatively minor importance (Table 1).

Table 1 Bullfrog diet described as relative frequency of occurrence (% Ocu), percentage of biomass (% Bio) and volume (% SV) in two invaded populations in Yunnan province, southwestern China.

(Continued Table 1)

3.2 Comparison among different bullfrog groups (adult males, females and juveniles) Although there was a weak positive relationship between bullfrog body size and prey biomass (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.188, P = 0.045) (Figure 2), we did not find significant relationships between bullfrog body size and prey volume (r = 0.093, P = 0.325), number of prey individuals (r = -0.054, P = 0.564), or number of prey species (r = 0.000, P = 0.998). The bullfrogs that consumed native frogs and those that did not use native frogs as prey did not differ in body size (Mann-Whitney U-test, z = -1.117, P = 0.264), weight (z = -1.469, P = 0.142), or mouth width (z = -1.284, P = 0.199). Finally, there was no difference in prey biomass (Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2= 4.57, d.f. = 2, P = 0.102), volume (χ2= 5.58, d.f. = 2, P = 0.061), number of prey individuals (χ2= 3.82, d.f. = 2, P = 0.148), or number of prey species (χ2= 3.20, d.f. = 2, P = 0.202) among males, females, and juveniles.

However, there were differences in diet composition among the bullfrog groups (Table 1). Although insects were the most frequent prey for females (37.4%), males (38.2%), and juveniles (42.0%), the adult bullfrogs consumed a large proportion of vertebrates, especially amphibians; Ranidae were the second most frequent (18.7%) and most abundant prey in terms of volume (41.8%) and biomass (44.9%) for female bullfrogs. Within Ranidae, B. pleuraden (10.9%) was predated more than bullfrog cannibalism (7.7%) by females, but bullfrog cannibalism represented a higher proportion with regard to biomass (27.2%) and volume (28.5%) than that of B. pleuraden (17.8% for biomass, 13.2% for volume). Ranidae also accounted for a large proportion of the food biomass (36.5%) and volume (33.8%) of males, followed by crustaceans (occurrence: 17.3%, volume: 30.0%, biomass: 29.7%) and fi shes (occurrence: 13.9%, volume: 13.3%, biomass: 11.2%). In contrast to the females, the males predated more frequently on B. pleuraden (6.9%), with a greater biomass (23.6%) and volume (21.1%) than those of bullfrog cannibalism (1.7% for occurrence, 12.9% for biomass, and 12.7% for volume). Following insects, the major diet category for juvenile bullfrogs was snail (occurrence: 38.0%, volume: 17.6%, biomass: 23.9%). We also detected other vertebrate prey including one Cypriniformes fish, one B. pleuraden, and another unidentifi ed frog in the stomachs of juveniles.

3.3 Variations between two populations There were variations in the bullfrog prey compositions between two populations. Overall, ten items were shared by both frog populations, whereas only six items appeared exclusively in the Caohai population and only 18 items occurred exclusively in the Shiping population (Table 1). For the Shiping population, the crayfi sh P. clarkii was a very frequent food, accounting for more than 30% of the total volume and more than 25% of the total biomass. Palaemonidae crustaceans were another dominant food, with more than 20% of the individual occurrences. We recorded one red-banded snake (Dinodon rufozonatum) in the stomach of a female bullfrog in Shiping, but the bullfrogs there rarely predated on amphibians (one bullfrog tadpole and two unidentifi ed frogs). In contrast, we detected more amphibian prey items in the Caohai bullfrogs, with bullfrog cannibalism representing over 36% and B. pleuraden over 30% of the total volume, and over 37% and 40% of the total biomass, respectively. The B. pleuraden had a high frequency of occurrence, present in more than 15% of the total bullfrogs. Cypriniformes fishes were also important prey (12.9% of volumes, 10.3% of biomass, and 21.9% of prey individuals).

After controlling for the bullfrog body size, we foundthat there were no signifi cant differences in prey biomass (ANCOVA; F = 0.22, d.f. = 1, P = 0.644) or volumes (F = 0.03, d.f. = 1, P = 0.856) between the two populations. However, the bullfrogs in the Shiping population consumed more prey individuals (F = 6.69, d.f. = 1, P = 0.011), and tended to have more prey species (F = 3.82, d.f. = 1, P = 0.053).

3.4 Prey selection by bullfrogs The abundance of the two native amphibian species in the environment was 0.16 ± 0.014 individuals/m (mean ± S.E.) and 1.29 ± 0.032 g/m for the B. pleuraden, and 0.07 ± 0.012 individuals/ m and 1.98 ± 0.310 g/m for the B. maxima. Concerning prey individuals, B. pleuraden and Cypriniformes fi shes were the preferred bullfrog prey items, whereas bullfrog cannibalism were avoided (Figure 3). Nevertheless, there was no difference between the two preferred items (Mann-Whitney U-test, z = -0.53, P = 0.599). In contrast, regarding prey biomass, B. pleuraden and bullfrog were preferred, and Cypriniformes fi shes were avoided (Figure 3). We did not fi nd a signifi cant difference in preference between B. pleuraden and bullfrog cannibalism (z = -1.38, P = 0.171). Specifi cally, B. maxima was captured in transects but was absent in the bullfrogs’ stomachs, and thus the Jacobs’ index (= -1) showed a total avoidance of this toad by the bullfrogs (Figure 3).

4. Discussion

This study is the first report of the invasive American bullfrog’s diet in Yunnan Province, southwestern China, and to the best of our knowledge, provides the first quantitative study of bullfrog prey selection in the context of the local anuran assemblage and other aquatic preys among their invaded ranges. Insects were the most frequent prey category, with the richest species diversity, which is consistent with previous studies both in their invaded ranges, such as in Argentina (Barrasso et al., 2009), Canada (Govindarajulu et al., 2006; Jancowski and Orchard, 2013), Germany (Laufer, 2004), the western USA (e.g., Hothem et al., 2009; Krupa, 2002), and Venezuela (Diaz de Pascual and Guerrero, 2008), and their native ranges (e.g., Werner et al., 1995). This was not surprising, as insects have a relatively large abundance and availability in the environment, and are usually the most frequently consumed prey item of frogs (Yousaf et al., 2010). We also confirmed that crayfish is an important prey of the bullfrog, as previously found in the Zhoushan Archipelago, China (Wu et al., 2005), Tokyo, Japan (Hirai, 2004), and California, USA (Carpenter et al., 2002; Clarkson and deVos, 1986), and their native ranges including Kentucky (Bush, 1959), Eastern Texas (Penn, 1950), Oklahoma (McCoy, 1967; Tyler and Hoestenbach, 1979), Arkansas (McKamie and Heidt, 1947), Ohio (Bruggers, 1973), and Missouri (Korschgen and Baskett, 1963; Korschgen and Moyle, 1955). One interesting fi nding in our study was that the red-swamp crayfi sh was one major prey of the bullfrogs in Shiping, where this crayfi sh has invaded (Liu and Li, 2009). However, with the absence of crayfi sh in Caohai, anurans comprised a large proportion of the total prey volume. Positive interactions among invaders (termed“invasional meltdown”) are considered a phenomenon that exacerbates the impacts of different invaders on native species (Simberloff and Von Holle, 1999). For example, in Oregon, USA, the invasion of bullfrogs was found to be facilitated by co-evolved non-native fishes (Adams et al., 2003). However, our findings indicated that one invader (e.g., bullfrog) might be able to reduce the negative effect of another (e.g., crayfish) on native species, especially when one was the favorite prey of the other. However, this conclusion should be made with caution, as the crayfi sh is also known as an alien predator of amphibians (Kats and Ferrer, 2003; Wu et al. 2008). Therefore, the interactions of different invaders on native species might be very complex, which requires further investigations with the aid of mesocosms experiments.Alternatively, as we did not conduct prey selection studies on the Shiping population due to difficulty in aquatic organism sampling, the high proportion of crayfish in the bullfrogs’ stomachs might merely be due to the high availability of the crayfi sh in the environment.

We found that the invasive bullfrogs predated on some vertebrates, particularly the amphibians in our study area. The consumption of native anurans by bullfrogs has been widely recorded in the Zhoushan Archipelago of China (Wang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2005), and other regions of the world (see review of Bury and Whelan, 1985). Collectively, we provide the first evidence of bullfrog predation on endemic species in China. Predation on endemics means a more severe impact of this invader on native amphibians because these endemic species are only distributed in China and their extinctions will result in irretrievable loss to the local biodiversity. The predation preference of the bullfrog on B. pleuraden suggests that it might be one potential mechanism behind the declining population trend of this endemic species (Yang and Lu, 2004). Our findings also indirectly demonstrate that a previous postulation might be true: that bullfrogs were hypothesized as a major factor causing the decline and even extinction of two endemic amphibian species, Cynops wolterstorffi in Dian Lake, Yunnan Province (He, 1998), and Paa liui in Lugu Lake (Li and Xie, 2004). Indeed, our field surveys since 2008 did not record the presence of P. liui in Caohai. We argue that future studies could be undertaken by investigating stomach contents of preserved museum specimens of bullfrogs to explore its predation history on these endemics. Although the bullfrog is generally recognized as an opportunistic generalist predator, it has been suggested that ranids are preferred by bullfrogs compared with other anurans (see review in Werner et al., 1995). Our feeding preference study quantitatively verified that the Yunnan pond frog, B. pleuraden, was selected by the bullfrog in terms of both the number of individuals and the biomass, whereas another endemic toad, B. maxima, was completely avoided by the bullfrog although several previous studies have recorded the predation of toad species by the bullfrog (e.g., Reis et al., 2007; Silva et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2005). However, this was consistent with another bullfrog predation selection study which found that toad was completely avoided among anuran preys by the bullfrog in southern Brazil (Boelter et al., 2012). Previous studies have suggested that the habitat use of native frogs could infl uence their predation by bullfrogs (Silva et al., 2011); therefore, one mechanism involved might be related to the difference in habitat use between the toad and bullfrog (Fei et al., 1999). For example, although they could both inhibit in the permanent still waters, the B. maxima could also use those slow streams (Fei et al., 1999), where the bullfrogs rarely select (Wang and Li, 2009). Another potential explanation might be that toads are less palatable than are frogs to the bullfrog due to their dermal toxins (Ahola et al., 2006; Pearl and Hayes, 2002). Finally, the finding might also simply reflect the low abundance of this toad in the habitat observed in the fi eld survey (Liu and Li, 2009). Theoretically, the body size of predators could infl uence their predation on native frogs (Wang et al., 2007; Silva et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2011). However, we did not fi nd effects of body size, weight, or mouth width on the predation of natives, indicating that smaller bullfrogs might not have less predation impacts on native frogs. Therefore, conservation attentions should be given irrespective of bullfrog body size.

We recorded a high prevalence of the cannibalism in both populations of the bullfrogs. Cannibalism in bullfrog was previously reported both in their native ranges (Korschgen and Moyle, 1955) and in areas where they have invaded (e.g., Barrasso et al., 2009; Diaz de Pascual and Guerrero, 2008; Govindarajulu et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2009). However, our feeding preference analysis showed that the bullfrog preferred the juvenile bullfrogs and tadpoles in terms of biomass but tended to avoid them in terms of the number of individuals, indicating that the cannibalism of bullfrogs might be not due to a selection process and merely may be due to the high energy that bullfrog tadpoles provide.

We also recorded a native red-banded snake predated by a bullfrog in the Shiping population. This was not surprising as previous studies have reported that the bullfrogs can prey upon reptiles, such as turtles and snakes (e.g., Clarkson and deVos, 1986; McKamie and Heidt, 1947). Nevertheless, it was interesting that previous studies found that bullfrogs in the Zhoushan Archipelago were the favorite prey of the red-banded snake (Li et al., 2011), and the water snake (Liophis miliaris) was also observed preying on juveniles of the bullfrogs in southeastern Brazil (Silva and Filho, 2009). Although we only recorded a single incidence of predation of the snake by the bullfrog, our results at least suggest that the reciprocal predation might exist between the two species, as they are naïve to each other. The fi nal output might be dependent on the comparison with regard to relative body size and other predation ability characteristics between the bullfrog and the snake, which warrants further investigations.

Although previous studies suggested that largerbullfrogs of both sexes predated more prey individuals and a greater biomass than smaller bullfrogs (Wu et al., 2005), we found that the occurrence, biomass and volume of diet items were generally independent of bullfrog size or mouth width, despite a weak positive relationship between the bullfrog body size and prey biomass in our study populations. An alternative explanation might be due to the smaller range in SVL of bullfrogs than that of the previous study (Wu et al., 2005). However, we found that there were differences in diet composition among males, females, and juveniles. One potential explanation is due to size-related ontogenetic diet variation between adults and juveniles (Blackburn and Moreau, 2006), or sex-dependent variations in prey compositions (Quiroga et al., 2009). Despite that the Caohai (higher elevation) population of bullfrogs exhibited a smaller body size (Liu et al., 2010), we did not observe any signifi cant difference in prey volume or biomass between the two populations. Nevertheless, we detected a difference in diet composition between two sampling sites. This might be infl uenced by the difference in prey availability between the two sites, which needs future investigations.

We acknowledged that we only found one endemic species and did not detect more native amphibian species in the bullfrog’s diet. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the predation impact of the American bullfrog on native anurans might be limited. For the two frog species (O. andersonii and P. liui) not detected but occurred historically, the bullfrog may have predated them to extinction since invasion and thus they might have experienced a “ghost of predation past”. Alternatively, it is known that stomach content analyses are always infl uenced by the degree of digestion, which can make it diffi cult to identify all their consumed species, especially for vertebrates (Hothem et al., 2009). This might also be another potential reason on why we did not fi nd a strong positive relationship of bullfrog size with prey measures. We recommend that further, more intensive samplings across more invaded populations be performed in order to assess the consumption of other native anuran species by bullfrogs. Furthermore, in addition to the direct predation impacts, we also detected the amphibian chytrid fungus B. dendrobatidis both in the fi eld and in museum historical bullfrog specimens from our study area (Bai et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2014a). Furthermore, a new chytrid species, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, isolated from infected Salamandra salamandra in the Netherlands, has been identified to cause rapid mortality in infected fi re salamanders (Martel et al., 2013). Although a recent study tested negative for B. salamandrivorans in the bullfrog samples from Yunnan Province (Zhu et al., 2014b), it is known as a potential disease-tolerant carrier for chytrid fungi (Garner et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2013b). Thus we urge the development of effective conservation and monitoring strategies to prevent the further spread of this notorious invader to more habitats and eliminate their negative impacts on native communities.

Acknowledgements We thank the anonymous villagers in Zhawoluo, Caohai, Lugu Lake for assisting with our field work. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments that have greatly improved this manuscript. This research was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31200416 and 31370545). The collection and handling of amphibians were conducted by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Project No. 2008/73). All staff, fellows and students received appropriate training before performing animal studies.

References

Adams M. J., Pearl C. A., Bury R. B. 2003. Indirect facilitation of an anuran invasion by non-native fishes. Ecol Lett, 6(4): 343-351

Ahola M., Nordström M., Banks P. B., Laanetu N., Korpimäki E. 2006. Alien mink predation induces prolonged declines in archipelago amphibians. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci, 273(1591): 1261-1265

Austin J. D., Davila J. A., Lougheed S. C., Boag P. T. 2003. Genetic evidence for female-biased dispersal in the bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana (Ranidae). Mol Ecol, 12(11): 3165-3172

Bai C. M., Liu X., Fisher M. C., Garner T. W. J., Li Y. M. 2012. Global and endemic Asian lineages of the emerging pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis widely infect amphibians in China. Divers Distrib, 18(3): 307-318

Barrasso D. A., Cajade R., Nenda S. J., Baloriani G., Herrera R. 2009. Introduction of the American Bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus (Anura: Ranidae) in natural and modified environments: an increasing conservation problem in Argentina. S Am J Herpetol, 4(1): 69-75

Blackburn D. C., Moreau C. S. 2006. Ontogenetic diet change in the arthroleptid frog Schoutedenella xenodactyloides. J Herpetol, 40(3): 388-394

Blanco-Garrido F., Prenda J., Narvaez M. 2008. Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) diet and prey selection in Mediterranean streams invaded by centrarchid fi shes. Biol Invasions, 10(5): 641-648

Boelter R. A., Kaefer I. L., Both C., Cechin S. 2012. Invasive bullfrogs as predators in a Neotropical assemblage: What frog species do they eat? Anim Biol, 62(4): 397-408

Bruggers R. L. 1973. Food habits of bullfrogs in Northwest Ohio. Ohio J Science 73: 185-188

Bury R. B., Whelan J. A. 1985. Ecology and Management of theBullfrog. US Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service

Bush F. M. 1959. Foods of some Kentucky herptiles. Herpetologica, 15(2): 73-77

Carpenter N. M., Casazza M. L., Wylie G. D. 2002. Rana catesbeiana (bullfrog) diet. Herpetol Rev, 33: 130

Clarkson R. W., Devos J. C. Jr. 1986. The Bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana Shaw, in the Lower Colorado River, Arizona-California. J Herpetol, 20(1): 42-49

D’Amore A., Kirby E., Hemingway V. 2006. Reproductive interference by an invasive species: An evolutionary trap? Herpetol Conserv Bio, 4(3): 325-330

Diaz de Pascual A., Guerrero C. 2008. Diet composition of bullfrogs, Rana catesbeiana (Anura: Ranidae) introduced into the Venezuelan Andes. Herpetol Rev, 39(4): 425

Ficetola G. F., Thuiller W., Miaud C. 2007. Prediction and validation of the potential global distribution of a problematic alien invasive species - the American bullfrog. Divers Distrib, 13(4): 476-485

Fei L., Ye C. Y., Huang Y. Z., Liu M. Y. 1999. Atlas of Amphibians of China. Zhengzhou: Henan Press of Science and Technology

Garner T. W. J., Perkins M. W., Govindarajulu P., Seglie D., Walker S., Cunningham A. A., Fisher M. C. 2006. The emerging amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis globally infects introduced populations of the North American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana. Biol Lett, 2(3): 455-459

Govindarajulu P., Altwegg R., Anholt B. R. 2005. Matrix model investigation of invasive species control: Bullfrogs on Vancouver Island. Ecol Appl, 15(6): 2161-2170

Govindarajulu P., Price W. S., Anholt B. R. 2006. Introduced bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) in western Canada: Has their ecology diverged? J Herpetol, 40(2): 249-260

Hayward M. W., Henschel P., O’Brien J., Hofmeyr M., Balme G., Kerley G. 2006. Prey preferences of the leopard (Panthera pardus). J Zool, 270(2): 298-313

He X. R. 1998. Cynops wolterstorffi, an analysis of the factors caused its extinction. Sichuan J Zool, 17(2): 58-60

Hirai T. 2004. Diet composition of introduced bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, in the Mizorogaike Pond of Kyoto, Japan. Ecol Res, 19(4): 375-380

Hothem R. L., Meckstroth A. M., Wegner K. E., Jennings M. R., Crayon J. J. 2009. Diets of Three Species of Anurans from the Cache Creek Watershed, California, USA. J Herpetol, 43(2): 275-283

Jacobs J. 1974. Quantitative measurement of food selection. Oecologia, 14(4): 413-417

Jancowski K., Orchard S. A. 2013. Stomach contents from invasive American bullfrogs Rana catesbeiana (= Lithobates catesbeianus) on southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. NeoBiota, 16: 17-37

Kats L. B., Ferrer R. P. 2003. Alien predators and amphibian declines: review of two decades of science and the transition to conservation. Divers Distrib, 9(2): 99-110

Kiesecker J. M., Blaustein A. R., Miller C. L. 2001. Potential mechanisms underlying the displacement of native red-legged frogs by introduced bullfrogs. Ecology, 82(7): 1964-1970

Korschgen L. J., Baskett T. S. 1963. Foods of Impoundment- and Stream-Dwelling Bullfrogs in Missouri. Herpetologica, 19(2): 89-99

Korschgen L. J., Moyle D. L. 1955. Food Habits of the Bullfrog in Central Missouri Farm Ponds. Am Midl Nat, 54(2): 332-341

Kraus F. 2009. Alien reptiles and amphibians: A scientific compendium and analysis. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

Krupa J. J. 2002. Temporal shift in diet in a population of American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) in Carlsbad Caverns National Park. Southwest Nat, 47(3): 461-467

Kupferberg S. J. 1997. Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) invasion of a California river: The role of larval competition. Ecology, 78(6): 1736-1751

Laufer H. 2004. Zum beutespektrum einer population von Ochsenfröschen (Amphibia: Anura: Ranidae) nördlich von Karlsruhe (Baden-Württemnerg Deutschland). Faun Abh, 25: 139-150

Leivas P. T., Leivas F. W., Moura M. O. 2012. Diet and trophic niche of Lithobates catesbeianus (Amphibia: Anura). Zoologia, 29(5): 405-412

Li C., Xie F. 2004. Invasion of bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana Show) in China and its management strategies. Chin J Appl Environ Biol, 10(1): 95-98

Li Y. M., Ke Z. W., Wang Y. H., Blackburn T. M. 2011. Frog community responses to recent American bullfrog invasions. Curr Zool, 57(1): 83-92

Li Y. M., Liu X., Li X. P., Petitpierre B., Guisan A. 2014. Residence time, expansion toward the equator in the invaded range and native range size matter to climatic niche shifts in non-native species. Global Ecol Biogeogr, 23(10): 1094-1104

Li Y. M., Wu Z. J., Duncan R. P. 2006. Why islands are easier to invade: human infl uences on bullfrog invasion in the Zhoushan archipelago and neighboring mainland China. Oecologia, 148(1): 129-136

Liu X., Li X. P., Liu Z. T., Tingley R., Kraus F., Guo Z. M., Li Y. M. 2014. Congener diversity, topographic heterogeneity and human-assisted dispersal predict spread rates of alien herpetofauna at a global scale. Ecol Lett, 17(7): 821-829

Liu X., Li Y. M. 2009. Aquaculture Enclosures Relate to the Establishment of Feral Populations of Introduced Species. PLoS ONE, 4(7): e6199. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0006199

Liu X., Li Y. M., Mcgarrity M. E. 2010. Geographical variation in body size and sexual size dimorphism of introduced American bullfrogs in southwestern China. Biol Invasions, 12(7): 2037-2047

Liu X., Mcgarrity M. E., Bai C. M., Ke Z. W., Li Y. M. 2013a. Ecological knowledge reduces religious release of invasive species. Ecosphere, 4(2): art21

Liu X., Mcgarrity M. E., Li Y. M. 2012. The influence of traditional Buddhist wildlife release on biological invasions. Conserv Lett, 5(2): 107-114

Liu X., Rohr J. R., Li Y. M. 2013b. Climate, vegetation, introduced hosts and trade shape a global wildlife pandemic. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci, 280(1753): 20122506

Liu X., Guo Z. W., Ke Z. W., Wang S. P., Li Y. M. 2011. Increasing Potential Risk of a Global Aquatic Invader in Europe in Contrast to Other Continents under Future Climate Change. PLoS ONE, 6(3): e18429. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018429

Lopez-Flores M., Vilella F. J. 2003. Predation of a White-cheeked Pintail (Anas bahamensis) Duckling by a Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). Caribb J Sci, 39(2): 240-241

Magnusson W. E., Lima A. P., da Silva W. A., De Araújo M. C. 2003. Use geometric forms to estimate volume of invertebrates in ecological studies of dietary overlap. Copeia, 2003(1): 13-19

Martel A., Spitzen-van der Sluijs A., Blooi M., Bert W., Ducatelle R., Fisher M. C., Woeltjes A., Bosman W., Chiers K., Bossuyt F., Pasmans F. 2013. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. causes lethal chytridiomycosis in amphibians. P Natl Acad Sci USA, 110(38): 15325-15329

McCoy C. J. 2005. Diet of bullfrogs Rana catesbeiana in central Oklahoma farm ponds. P Okla Acad Sci, 39(4): 668-674

McKamie J. A., Heidt G. A. 1947. A comparison of spring food habits of the bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, in three habitats of central Arkansas. Southwest Nat, 19: 107-111

Myers N., Mittermeier R. A., Mittermeier C. G., da Fonseca G. A. B., Kent J. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403(6772): 853-858

Olden J. D., Rooney T. P. 2006. On defi ning and quantifying biotic homogenization. Global Ecol Biogeogr, 15(2): 113-120

Pearl C. A., Adams M. J., Bury R. B., Mccreary B. 2004. Asymmetrical effects of introduced bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) on native ranid frogs in Oregon. Copeia, 2004: 11-20

Pearl C. A., Hayes M. P. 2002. Predation by Oregon spotted frogs (Rana pretiosa) on western toads (Bufo boreas) in Oregon. Am Midl Nat, 147(1): 145-152

Pearl C. A., Hayes M. P., Haycock R., Engler J. D., Bowerman J. 2005. Observations of interspecifi c amplexus between western North American ranid frogs and the introduced American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) and an hypothesis concerning breeding interference. Am Midl Nat, 154(1): 126-134

Penn G. H. 1950. Utilization of Crawfishes by Cold-Blooded Vertebrates in the Eastern United States. Am Midl Nat, 44(3): 643-658

Quiroga L. B., Sanabria E. A., Acosta J. C. 2009. Size-and sexdependent variation in diet of Rhinella arenarum (Anura: Bufonidae) in a wetland of San Juan, Argentina. J Herpetol, 43(2): 311-317

R Development Core Team R. D. 2012. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Reis E. P., Silva E. T., Feio R. N., Ribeiro Filho O. P. 2007. Chaunus pombali (Pombali’s toad) Predation. Herpetol Rev, 38(3): 321

Silva E. T., Filho O. P. R. 2009. Predation on juveniles of the invasive American Bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus (Anura, Ranidae) by native frog and snake species in South-eastern Brazil. Herpetol Notes, 2: 215-218

Silva E. T., Filho O. P. R., Feio R. N. 2011. Predation of Native Anurans by invasive bullfrogs in southeastern Brazil: spatial variation and effect of microhabitat use by prey. S Am J Herpetol, 6(1): 1-10

Silva E. T., Reis E. P. D., Feio R. N., Filho O. P. R. 2009. Diet of the Invasive Frog Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802) (Anura: Ranidae) in Viçosa, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. S Am J Herpetol, 4(3): 286-294

Simberloff D., Von Holle B. 1999. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: invasional meltdown? Biol Invasions, 1(1): 21-32

Stuart S. N., Chanson J. S., Cox N. A., Young B. E., Rodrigues A. S. L., Fischman D. L., Waller R. W. 2004. Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science, 306(5702): 1783-1786

Tyler J. D., Hoestenbach R. D. Jr. 1979. Differences in food of bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) from pond and stream habitats in southwestern Oklahoma. Southwest Nat, 24: 33-38

Wang Y. H., Li Y. M. 2009. Habitat Selection by the Introduced American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) on Daishan Island, China. J Herpetol, 43(2): 205-211

Wang Y. P., Wang Y. H., Lu P., Zhang F., Li Y. M. 2005. Diet composition of post-metamorphic bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) in the Zhoushan archipelago, Zhejiang Province. Chin Biodiv, 14(5): 363-371

Wang Y. P., Guo Z. W., Pearl C. A., Li Y. M. 2007. Body size affects the predatory interactions between introduced American Bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) and native anurans in China: An experimental study. J Herpetol, 41(3): 514-520

Werner E. E., Wellborn G. A., Mcpeek M. A. 1995. Diet composition in postmetamorphic bullfrogs and green frogs: implications for interspecific predation and competition. J Herpetol, 29(4): 600-607

Wu Z. J., Cai F. J., Jia Y. F., Lu J. X., Jiang Y. F., Huang C. M. 2008. Predation impact of Procambarus clarkii on Rana limnocharis tadpoles in Guilin area. Biodiv Sci, 16(2): 150-155

Wu Z. J., Li Y. M., Wang Y. P., Adams M. J. 2005. Diet of introduced Bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana): Predation on and diet overlap with native frogs on Daishan Island, China. J Herpetol, 39(4): 668-674

Xie F., Lau M. W. N., Stuart S. N., Chanson J. S., Cox N. A., Fischman D. L. 2007. Conservation needs of amphibians in China: A review. Sci China C Life Sci, 50(2): 265-276

Yang D. T., Li S., Liu W., Lu S. 1991. Amphibian Fauna of Yunnan, China. Beijing: Forestry Publishing House

Yang D. T., Lu S. Q. 2004. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Version 20142. Retrieved from http://www.iucnredlist.org Downloaded on 11 August 2014

Yousaf S., Mahmood T., Rais M., Qureshi I. Z. 2010. Population Variation and Food Habits of Ranid Frogs in the Rice-Based Cropping System in Gujranwala Region, Pakistan. Asian Herptol Res, 1(2): 122-130

Zhu W., Bai C. M., Wang S. P., Soto-Azat C., Li X. P., Liu X., Li Y. M. 2014a. Retrospective Survey of Museum Specimens Reveals Historically Widespread Presence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in China. EcoHealth, 11(2): 241-250

Zhu W., Xu F., Bai C. M., Liu X., Wang S. P., Gao X., Yan S. F., Li X. P., Liu Z. T., Li Y. M. 2014b. A survey for Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in Chinese amphibians. Curr Zool, 60(6): 729-735

Prof. Yiming LI, from Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, with his research focusing on conservation biology and ecology of amphibians, and macroecology of vertebrates.

E-mail: liym@ioz.ac.cn

12 August 2014 Accepted: 7 December 2014

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- First Records of Megophrys daweimontis Rao and Yang, 1997 and Amolops vitreus (Bain, Stuart and Orlov, 2006) (Anura: Megophryidae, Ranidae) from Vietnam

- Development and Evaluation of a Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplif cation (LAMP) Assay for Rapid Detection of Chinese Giant Salamander Ranavirus

- Antipredator Behavioral Responses of Native and Exotic Tadpoles to Novel Predator

- Prehibernation Energy Storage in Heilongjiang Brown Frogs (Rana amurensis) from Five Populations in North China

- Preliminary Report on the Anurans of Mount Hilong-hilong, Agusan Del Norte, Eastern Mindanao, Philippines

- A New Species of Odorrana Inhabiting Complete Darkness in a Karst Cave in Guangxi, China