老年急性胰腺炎临床特点和治疗分析

2015-04-21吴鹏飞戴存才蒋奎荣吴峻立高文涛陈建敏卫积书陆子鹏黄东亚

吴鹏飞,苗 毅,李 强,戴存才,蒋奎荣,吴峻立,高文涛,郭 峰,陈建敏,卫积书,陆子鹏,黄东亚

老年急性胰腺炎临床特点和治疗分析

吴鹏飞,苗 毅,李 强*,戴存才,蒋奎荣,吴峻立,高文涛,郭 峰,陈建敏,卫积书,陆子鹏,黄东亚

(南京医科大学第一附属医院胰腺中心,南京 210029)

探讨老年急性胰腺炎(AP)患者的临床特征和诊疗效果。回顾性地分析南京医科大学第一附属医院胰腺中心2012年1月至2014年12月期间收治的164例老年AP患者(老年组,年龄≥60岁)临床特征和疗效,并与同期收治的309例非老年AP患者(对照组,年龄<60岁)进行对比分析。老年组AP的主要病因为胆道疾病,其次为高脂血症,老年组胆源性AP发生率明显高于对照组(84.15%59.55%,<0.001),高脂血症性AP发生率明显低于对照组(9.14%31.07%,<0.001)。老年组和对照组主要全身并发症均为脏器功能衰竭(20.12%18.77%,>0.05),但老年组全身感染和持续性全身炎症反应综合征发生率明显高于对照组,两组间差异具有统计学意义(<0.05),两组间局部并发症发生率无统计学差异(>0.05)。老年组重症急性胰腺炎(SAP)发生率与对照组相当(18.90%18.77%),但病死率明显高于对照组(7.93%3.56%,<0.05)。老年AP患者合并基础疾病多,易发生全身并发症,发展为SAP后病死率高,临床应予以早期诊断和有效治疗,可改善老年AP患者的预后。

胰腺炎,急性;老年人;临床特点;治疗

急性胰腺炎(acute pancreatitis,AP)是临床常见的急腹症,大多数患者病程呈自限性,预后良好。20%~30%的AP患者临床经过凶险,发展为重症急性胰腺炎(severe acute pancreatitis,SAP),总体病死率为5%~10%[1,2]。近年来,老年AP的发病率呈现逐年上升的趋势,且老年AP的临床表现及诊治具有一定特殊性。本研究收集南京医科大学第一附属医院胰腺中心收治的老年AP患者临床资料,并对其临床特点和治疗效果进行回顾性分析。

1 对象与方法

1.1 研究对象

收集2012年1月至2014年12月期间南京医科大学第一附属医院胰腺中心收治的AP患者473例,其中老年组(年龄≥60岁)164例,男性81例,女性83例,年龄60~91岁,中位年龄68.5岁;对照组(年龄<60岁)309例,男性176例,女性133例,年龄17~59岁,中位年龄45.0岁。

所有患者均根据《中国急性胰腺炎诊治指南(2013,上海)》AP的诊断标准[3],临床上符合以下3项特征中的2项,即可诊断为AP:(1)与AP符合的腹痛(急性、突发、持续、剧烈的上腹部疼痛,常向背部放射);(2)血清淀粉酶和(或)脂肪酶活性至少>3倍正常上限值;(3)增强CT/MRI或腹部超声呈AP影像学改变。最新Atlanta标准(2012年)按照严重程度将AP分为轻度急性胰腺炎(mild acute pancreatitis,MAP)、中度重症急性胰腺炎(moderately severe acute pancreatitis,MSAP)和SAP,SAP为符合AP诊断标准,伴有持续性(>48h)器官功能衰竭[4]。器官功能衰竭的诊断标准依据改良Marshall评分系统,任何器官评分≥2分可定义存在器官功能衰竭[5]。

1.2 统计学处理

资料收集完成后,采用SPSS19.0软件进行统计学分析。计数资料用百分率表示,两组间比较采用2检验。以<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结 果

2.1 两组AP患者病因分析

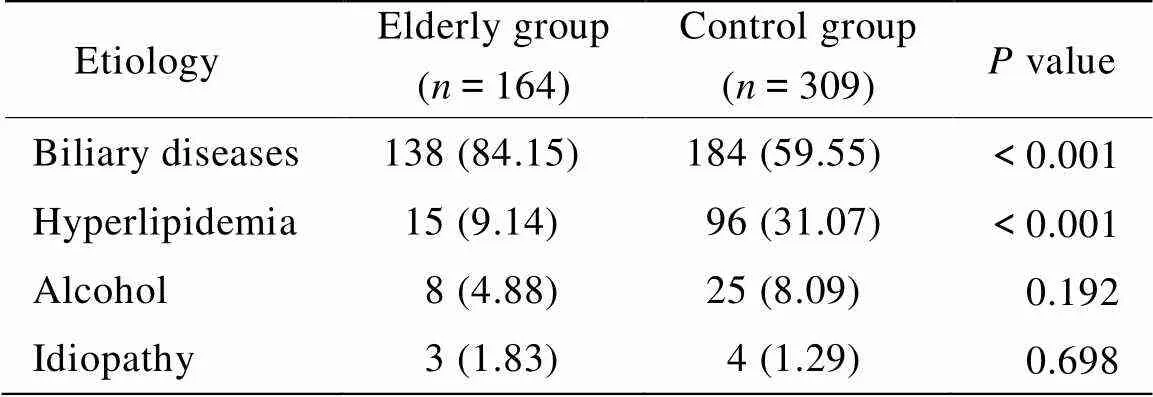

两组患者首要病因均为胆道疾病,其次为高脂血症,但老年组胆源性AP发生率明显高于对照组,高脂血症性AP明显低于对照组,两组比较差异均具有统计学意义(<0.001);酒精性AP和特发性AP,两组患者比较差异无统计学意义(>0.05;表1)。

表1 老年组与对照组病因的对比分析

2.2 两组AP患者并发症分析

老年组和对照组主要全身并发症均为器官功能衰竭,两组患者发生率间差异无统计学意义(>0.05);而老年组全身感染和持续性全身炎症反应综合征(systemic inflammatory response syndrome,SIRS)明显高于对照组,两组间差异具有统计学意义(<0.05)。局部并发症包括胰腺坏死、胰腺假性囊肿和腹腔出血,老年组与对照组发生率相当,差异无统计学意义(>0.05;表2)。

表2 老年组与对照组并发症的对比分析

SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome; IAH: intra-abdominal hypertension; ACS: abdominal compartment syndrome

2.3 两组AP患者疗效分析

所有患者入院均予心电监测,吸氧,禁食,胃肠减压,液体复苏改善微循环,抑制胃酸,抑制胰酶活性,预防/控制感染,维持内环境稳定,营养支持,动态监测器官功能等治疗。当患者出现器官功能衰竭或原有疾病恶化时,采取积极的抢救措施,除合理补液和药物治疗外,采用连续肾脏替代疗法、机械通气等。经临床规范化治疗后,老年组患者出现SAP 31例(18.90%),13例死亡(病死率7.93%),其余151例患者(92.07%)均好转出院(治愈129例,好转22例);对照组出现SAP 58例(18.77%),11例死亡(病死率3.56%),其余298例患者(96.44%)均好转出院(治愈225例,好转73例),两组患者间病死率差异具有统计学意义(<0.05)。

3 讨 论

随着生活水平的提高及人口的老龄化,老年AP发病率呈现逐年上升的趋势。本组老年AP患者的病因主要以胆源性为主,胆源性AP比例达84.15%,明显高于对照组;其次为高脂血症,由于饮食结构的变化,各种代谢紊乱疾病导致高脂血症明显增加;第三为酒精性,老年组略微少于对照组。老年AP患者,由于自身合并较多的基础疾病,如高血压、糖尿病、冠心病、脑血管疾病等,不但可使AP病情进一步恶化,而且可使原有疾病加重,故老年AP具有多病并存、病情重、合并症多、病死率高等特点。若未得到及时有效的治疗,则可能发生多器官功能不全综合征(multiple organ dysfunction syndrome,MODS),最终导致患者死亡[6]。本组老年AP患者中主要并发症为器官功能衰竭,以呼吸衰竭和肾功能衰竭为主,总体发生率为20.12%,且绝大多数患者为持续性器官功能衰竭,是造成老年AP患者高死亡率的最主要原因。

老年AP仍以腹痛为主要临床表现,可伴随发热、恶心、呕吐等症状,但与非老年AP患者相比,老年AP患者腹痛发生率较低。部分老年AP患者症状可仅表现为隐痛或无腹痛,以腹胀、食欲减退、上腹不适为主要表现,加之老年患者疼痛阈值高,敏感性低,反应能力差,易误诊误治。因此对老年患者临床疑诊为AP时,应注重对其行进一步实验室检查及影像学检查,尽早明确诊断,及时予以有效治疗。目前AP的影像学检查主要包括B超检查和CT扫描,超声检查操作简单、费用低,但具有一定的局限性,而CT扫描,尤其是增强CT扫描,不仅能很好地显示胰腺实质水肿、胰腺周围渗出,还能显示较大范围的液体积聚、出血、坏死和其他局部/全身并发症,是诊断AP的最佳影像学检查,临床上应常规应用[7,8]。

老年AP的治疗包括禁食、胃肠减压、早期液体复苏、镇痛、抑制胰腺分泌和适时营养支持等[9]。治疗期间监测生命体征,注意水电解质、肝肾功能变化,合理应用抗生素,同时应兼治并存疾病,如原有呼吸系统疾病者应联合用药,如有心血管疾病应加用扩血管药物并注意补液的量及速度,大部分老年AP可以通过内科治疗获得缓解[10]。若老年AP患者经过初始治疗后,症状无改善,出现呼吸衰竭或低血压的迹象,应考虑直接转入重症监护病房给予积极的静脉补液和严密监护[11]。

对于存在胆囊结石的老年MAP患者,应在患病同期行胆囊切除术治疗,以防止AP的复发。急性坏死性胆源性胰腺炎患者,安全的胆囊切除术应延期至急性炎症反应消退、胰周积液吸收或稳定>6周时进行[12,13]。老年AP患者胆总管结石持续存在可使胰管和胆管持续梗阻,导致SAP和胆管炎,解除结石导致的梗阻可降低相关并发症的发生率,因此合并急性胆管炎的AP患者应在住院后24h内行内镜下逆行胆胰管造影术(endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography,ERCP)检查和鼻胆管引流[14],胆管梗阻但无急性胆管炎的AP患者可择期行ERCP检查。无症状的包裹性坏死和假性囊肿形成的患者,不论其病变大小、位置和范围,都不需要干预治疗。SAP患者感染性坏死处于稳定期内,外科手术、介入、内镜等治疗应至少推迟至发病4周后进行[15]。对于存在感染性坏死灶且有症状的SAP患者,应优先考虑行微创坏死组织清除术[16]。

综上所述,老年AP是一种老年常见疾病,临床应早期给予明确的诊断和及时有效的治疗,尤其是SAP患者,提倡在多学科综合治疗模式下进行有效的综合治疗,以期获得最佳的治疗效果,提高临床治愈率。

[1] Singh VK, Bollen TL, Wu BU,. An assessment of the severity of interstitial pancreatitis[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 9(12): 1098−1103.

[2] Van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL,. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome[J]. Gastroenterology, 2011, 141(4): 1254−1263.

[3] Working Group of Pancreatic Disease in Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Editorial Board of, Editorial Board of. Chinese Guideline: Management of Acute Pancreatitis (2013, Shanghai) [J]. Chin J Dig, 2013, 33(7): 217−222. [中华医学会消化病学分会胰腺疾病学组, 《中华胰腺病杂志》编辑委员会, 《中华消化杂志》编辑委员会. 中国急性胰腺炎诊治指南(2013, 上海)[J]. 中华消化杂志, 2013, 33(7): 217−222.]

[4] Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C,. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus[J]. Gut, 2013, 62(1): 102−111.

[5] Wang S, Feng X, Li S,. The ability of current scoring systems in differentiating transient and persistent organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis[J]. J Crit Care, 2014, 29(4): 693, e7−e11.

[6] Lankisch PG, Apte M, Banks PA. Acute pancreatitis[J]. Lancet, 2015.Jan 20 pii: S0140-6736(14)60649-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60649-8. [Epub ahead of print]

[7] Sheu Y, Furlan A, Almusa O,. The revised Atlanta classification for acute pancreatitis: a CT imaging guide for radiologists[J]. Emerg Radiol, 2012, 19(3): 237−243.

[8] Pocard M, Soyer P. CT of acute pancreatitis: a matter of time[J]. Diagn Interv Imaging, 2015, 96(2): 129−131.

[9] De-Madaria E. Fluid therapy in acute pancreatitis[J]. Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 36(10): 631−640.

[10] Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis[J]. Pancreatology, 2013, 13(4 Suppl 2): e1−e15.

[11] Pavlidis P, Crichton S, Lemmich Smith J,. Improved outcome of severe acute pancreatitis in the intensive care unit[J]. Crit Care Res Pract, 2013, 2013: 897107.

[12] Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J,. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2013, 108(9): 1400−1415, 1416.

[13] Van Baal MC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ,. Timing of cholecystectomy after mild biliary pancreatitis: a systematic review[J]. Ann Surg, 2012, 255(5): 860−866.

[14] Fisher JM, Gardner TB. The “golden hours” of management in acute pancreatitis[J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012, 107(8): 1146−1150.

[15] Wu BU, Banks PA. Clinical management of patients with acute pancreatitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144(6): 1272−1281.

[16] Raraty MG, Halloran CM, Dodd S,. Minimal access retroperitoneal pancreatic necrosectomy: improvement in morbidity and mortality with a less invasive approach[J]. Ann Surg, 2010, 251(5): 787−793.

(编辑: 周宇红)

Clinical features and treatment of acute pancreatitis in elderly patients

WU Peng-Fei, MIAO Yi, LI Qiang*, DAI Cun-Cai, JIANG Kui-Rong, WU Jun-Li, GAO Wen-Tao, GUO Feng, CHEN Jian-Min, WEI Ji-Shu, LU Zi-Peng, HUANG Dong-Ya

(Pancreas Center, the First Affiliated Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, China)

To investigate the clinical features and treatment efficiency of acute pancreatitis (AP) in the elderly.The clinical data of 164 consecutive elderly patients (elderly group, aged over 60 years) with confirmed AP and 309 non-elderly AP patients (control group, younger than 60 years old) treated in our center in recent 3 years were collected and analyzed retrospectively. The clinical features and treatment efficiency were compared between the 2 groups.The most common etiology of AP in the elderly patients was biliary diseases, followed by hyperlipidemia. Compared to control group, the proportion of biliary AP was significantly higher (84.15%59.55%,<0.001); meanwhile, the percentage of hyperlipidemic AP was obviously lower (9.14%31.07%,<0.001). The main systemic complication was organ failure in both groups (20.12%18.77%,>0.05), but the incidence of systemic infection and persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome was significantly higher in the elderly group than in the control group (<0.05), and the incidence of local complications had no statistical difference between the 2 groups (>0.05). The incidence of severe AP was similar in the two groups (18.90%18.77%), however, the elderly group had significantly higher mortality (7.93%3.56%,<0.05).The elderly patients with AP are prone to have systemic complications due to their comorbidities, and then the AP may deteriorate into severe AP with extremely high mortality. Early diagnosis and effective treatment could improve the prognosis of the elderly patients with AP.

pancreatitis, acute; elderly; clinical features; therapy

R576; R592

A

10.11915/j.issn.1671-5403.2015.04.057

2015−02−09;

2015−03−09

南京医科大学第一附属医院创新团队项目

李 强, E-mail: liqiang020202@163.com