施肥和杂草多样性对土壤微生物群落的影响

2015-01-19赵灿灿何琼杰吕会会管奕欣谷艳芳

孙 锋, 赵灿灿, 何琼杰, 吕会会, 管奕欣, 谷艳芳,2,*

1 河南大学生命科学学院, 开封 475004 2 河南大学生态科学和技术研究所, 开封 475004

施肥和杂草多样性对土壤微生物群落的影响

孙 锋1, 赵灿灿1, 何琼杰1, 吕会会1, 管奕欣1, 谷艳芳1,2,*

1 河南大学生命科学学院, 开封 475004 2 河南大学生态科学和技术研究所, 开封 475004

常年使用化肥和除草剂以及农业新技术的高投入,使我国粮食主产区耕地出现了生产力降低、土壤生物多样性失调和污染严重等生态问题。采用磷脂脂肪酸(PLFA)方法来评估施肥和杂草多样性对冬小麦土壤微生物群落结构的影响。实验采用裂区实验设计,施肥作为主因素,杂草多样性作为次因素。化肥和有机肥两个施肥处理,在两个施肥处理中进行杂草多样性设置,实验盆中心种植作物(冬小麦8株),四周种植杂草(8株),杂草种类选择野燕麦、苜蓿、菊苣、播娘蒿。杂草多样性处理设为0、1、2、4种杂草处理,0种杂草处理仅种植作物,有6盆;1种杂草处理为每盆种1种杂草,有12盆;2种杂草处理为每盆种两种杂草,有12盆;4种杂草处理为每盆种4种杂草,有6盆。结果表明:在两种施肥处理中,增加杂草多样性显著增加了土壤碳氮比和pH值,碳氮比都是在4种杂草处理中最高。施化肥处理中,增加杂草多样性显著影响真菌和细菌比,真菌和细菌比在4种杂草处理中最大,显著高于0、1、2种杂草处理。在施有机肥处理中,增加杂草多样性显著影响阳性菌和阴性菌比,阳性菌和阴性菌比在0种杂草处理中最低,显著低于1、2、4种杂草处理。在两个施肥处理中,土壤碳氮比与各类群微生物量显著相关,杂草多样性通过改变土壤碳氮比改变微生物群落构成,并且微生物群落结构转变方式不同。

磷脂脂肪酸(PLFA); 施肥; 杂草多样性; 主要农作物

土壤生物在增加土壤碳储存、提高土壤肥力和调节植物生长中起着重要作用。尤其土壤微生物,它是土壤生态系统的关键成份和土壤功能(如物质循环,能量流动)的驱动者[1]。微生物之间通过竞争和其它相互作用可以降低真菌类疾病[2],而微生物与植物根系共生形成菌根真菌能提高植物对氮和磷的吸收[3]。因此,土壤微生物在提高土壤生态系统功能方面起着重要作用。

农田管理方式(如施化肥、除草剂等)直接或间接地影响土壤微生物群落构成。当前,大量化肥施用于农田用来满足人类食物需求[4]。人为的氮输入是100年前的10倍[5]。从1996年到2005年,中国的谷物产量增加了10%,但化肥施用量增加了51%[6]。土壤微生物群落结构和施肥有密切关系。长期施氮肥能减少总微生物量和真菌生物量[7-8],改变土壤氨氧化细菌群落构成[9]。长期施磷肥能显著减少真菌生物量[8,10]。因此,长期施化肥对微生物有不利影响。除草剂的大量使用,使农田杂草多样性急剧降低。农田杂草是栖息在农田中鸟类、昆虫和传粉动物的食物来源[11-12],同时也是地上地下生态系统密切联系的纽带,影响分解者生物群落组成(微生物、线虫、螨类)、养分利用和土壤生态过程的稳定性[13-14]。大量研究集中于杂草对作物产量的影响,而农田杂草如何影响土壤微生物群落结构的相关研究还比较少[15],且结果不一致[15-17]。微生物群落构成和多样性的改变对植被生产力的影响是未来的主要挑战[18]。

磷脂脂肪酸(PLFA)法不仅可以检测活体微生物群落结构而且可以估计微生物生物量。磷脂脂肪酸组成的改变被认为是微生物群落结构转变的敏感标记,广泛用来比较不同的土地利用系统、作物管理模式和营养压力下微生物群落的差异[19-20],是目前较可靠的研究方法。

常年使用化肥和农药以及农业新技术的高投入,使我国粮食主产区耕地出现了生产力降低、土壤生物多样性失调和污染严重等生态问题。保护生物多样性被认为是应对未来农业风险的重要战略[21]。本研究采用盆栽模拟试验探索施化肥和有机肥措施下增加杂草多样性是否改变冬小麦土壤微生物群落构成,以及该变化方式是否相同。旨在为农田土壤环境保持健康稳定提供一定的科学依据。基于该研究提出假设:(1)增加杂草多样性通过影响土壤C/ N改变微生物群落,(2)增加杂草多样性在两种施肥处理中改变微生物群落结构方式不同。

1 研究区域

试验地点位于河南省开封市河南大学试验田,地理位置为34°48′ N、114°18′ E,暖温带气候,受季风影响显著,四季分明,年均气温14 ℃,年均日照2267.6 h,年均降雨量为634.2 mm,属于半湿润偏干旱型,土壤为黄河冲积物母质发育而成,土层深厚,土质疏松。

2 研究方法

2.1 实验设计

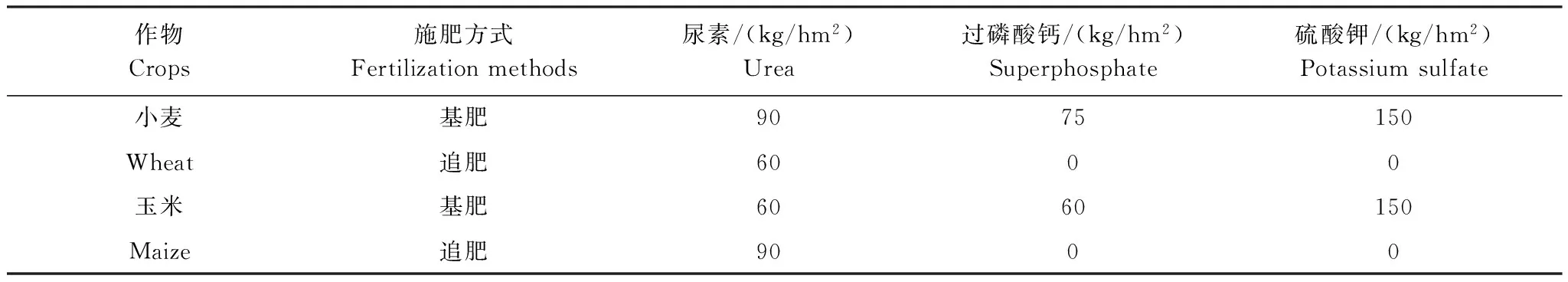

实验始于2010年10月,采用盆栽模拟方式(盆长75 cm,盆宽50 cm,盆高50 cm)种植作物为冬小麦(Triticumaestivum)和玉米(Zeamays)轮作,土壤取自撂荒地,原土壤化学性质全氮为0.30 g/ kg,铵态氮为16.1 mg/ kg,全磷为0.61 g/ kg,有效磷10.5 mg/ kg,有机碳3.2 g/ kg,pH为7.41。采用施肥作为主因素、杂草多样性作为次因素的裂区实验设计,化肥(NPK)和有机肥(OM)两个施肥处理,施化肥时间为冬小麦播前(10月,基肥)和拔节期(次年3月,追肥),施肥量如表1;有机肥为鸡粪经堆制发酵后作基肥施用(无追肥),施用前先分析氮养分含量,以和施化肥处理等氮量为标准,同长期定位试验[22]。在两个施肥处理中进行杂草多样性设置,杂草和冬小麦作物同时种植,玉米不种植杂草。实验盆中心种植作物(冬小麦8株),四周种植杂草(8株),杂草种类选择野燕麦(Avenafatua)、苜蓿(Medicagosativa)、菊苣(Cichoriumintybus)、播娘蒿(DescurainiaSophia)。杂草多样性处理设为0、1、2、4种杂草处理,0种杂草处理仅种植作物(冬小麦16株);1种杂草处理为每盆种1种杂草(8株);2种杂草处理为每盆种两种杂草、每种4株;4种杂草处理为每盆种4种杂草、每种2株。0种杂草处理有6个重复;1种杂草处理有4个组合(a, b, c, d),各3个重复共12盆;2种杂草有6种组合(ab, ac, ad, bc, bd, cd),各2个重复共12盆;4种杂草处理有一种组合(abcd)6个重复。共计72 (2种施肥处理×4种杂草不同组合的36个重复)个实验盆。

2.2 土壤样品采集及处理

在2013年(连续3a种植冬小麦,第3年取样)冬小麦开花期(4月30号),用直径2 cm土钻在实验盆中按五点法取0—20 cm土层土样,用镊子拣出根、凋落物碎屑及小石粒,混匀过2 mm土筛。分成两份,用无菌塑料袋装好,一份贮于-20 ℃冰箱用于微生物磷脂脂肪酸分析,一份自然风干用于测定土壤化学特性。

2.3 测定方法

2.3.1 土壤微生物量测定方法

采用磷脂脂肪酸(PLFA)生物标记法[23]。称量相当8 g干重的鲜土样,用23 mL含有氯仿、甲醇、磷酸盐缓冲液(1∶2∶0.8)的混合提取液萃取脂质,N2气体下浓缩萃取液。对磷脂进行分离,把脂肪酸恢复成甲酯,脂肪酸甲酯溶解在200 mL包含有十九烷酸甲酯(19:0)己烷溶剂中,19:0作为内部标准。采用安捷伦6890气相色谱仪分析磷脂脂肪酸样本,磷脂脂肪酸(PLFA)的鉴定采用细菌脂肪酸标准和MIDI峰鉴别软件。认定单一不饱和脂肪酸和环丙基脂肪酸为革兰氏阴性菌[24],a/ i支链脂肪酸为革兰氏阳性菌[25],脂肪酸14:0、15:0、16:0、17:0、18:0、革兰氏阴性菌和革兰氏阳性菌总和为细菌;16:1ω5c为菌根真菌标记[25];18:1ω9c和18:2ω6,9c为真菌标记[26]。

2.3.2 土壤化学特性测定方法

pH值分析采用0.01 mol/ L的CaCl2溶液浸提pH计法;土壤有机碳分析采用重铬酸钾氧化外加热法;土壤全氮分析采用半微量凯氏定氮法;铵态氮分析采用2 mol/ L的KCl浸提连续流动分析仪测定法。

2.4 数据处理与分析

用单因素方差分析判定杂草多样性对土壤化学性质、微生物生物量和群落比的影响;把植物初级生产量作为协变量,用协方差分析判定植物多样性对以上指标的影响;用LSD法表示显著性差异;Origin 8.0进行作图。

表1 试验地肥料使用量

3 结果

3.1 施肥和杂草多样性对土壤化学性质的影响

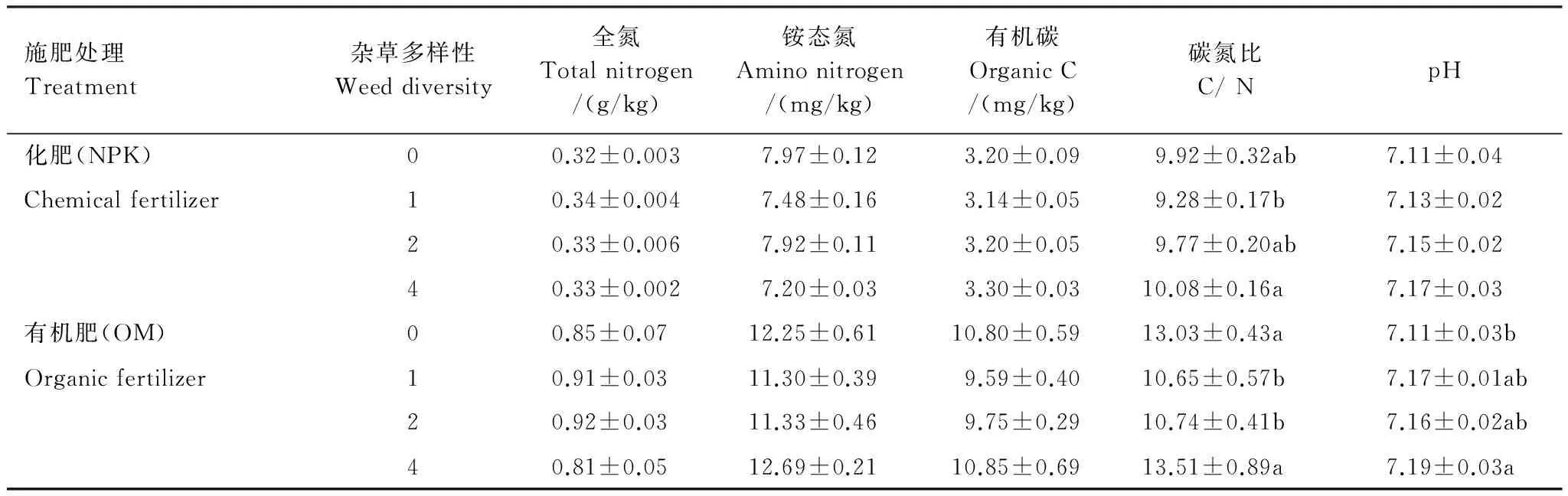

由表2可知:施化肥处理中,土壤全氮、铵态氮、有机碳、碳氮比和pH值均低于施有机肥。在施化肥处理中,杂草多样性对土壤全氮、铵态氮、有机碳和pH值无显著影响,碳氮比在4种杂草处理中最高,比1种杂草处理高8.6%,且有显著差异。在施有机肥处理中,杂草多样性显著影响土壤碳氮比和pH值;碳氮比在4种杂草处理中显著高于1种杂草和2种杂草处理;pH值在4种杂草处理中最高,在0种杂草处理中最低,且两处理间有显著差异。

表2 冬小麦开花期土壤养分

数据为平均值加标准误,0种草和4种草处理重复6次,1种草和2种草处理重复12次

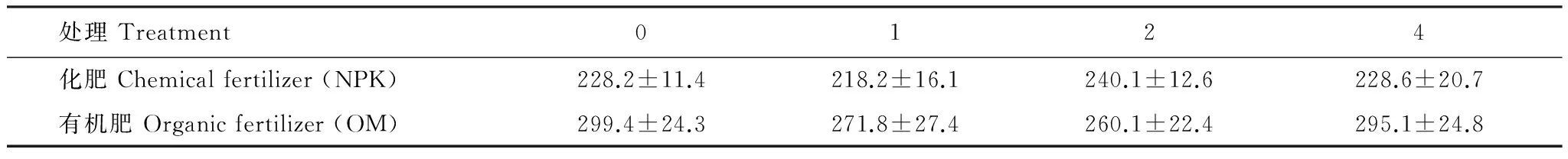

3.2 施肥和杂草多样性对初级生产量的影响

由表3可知:在两个施肥处理中,杂草多样性对初级生产量无显著影响。施有机肥各个杂草多样性处理初级生产量均高于施化肥处理。

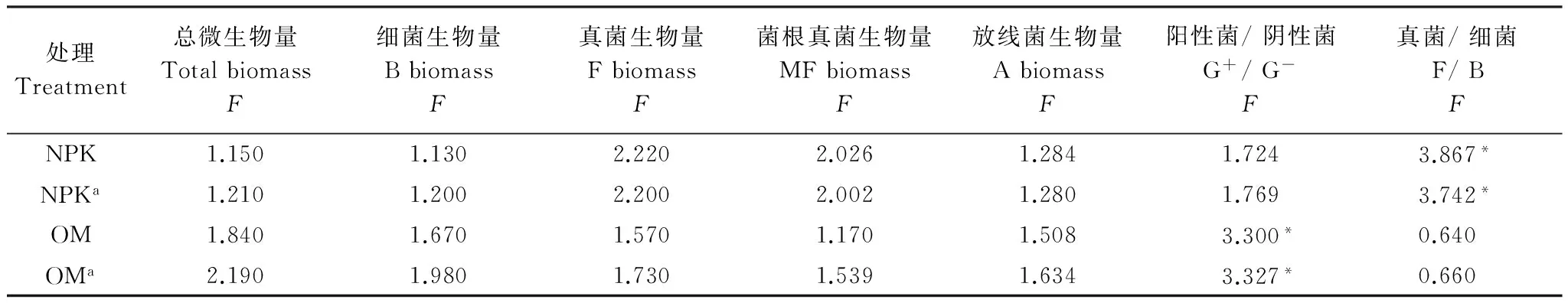

3.3 施肥和杂草多样性对土壤微生物的影响

由表4可见:在NPK施肥处理中,杂草多样性显著影响真菌和细菌比;在OM处理中,杂草多样性显著影响阳性菌和阴性菌比;在两个施肥处理中,把初级生产量作为协变量后,仍有显著差异。

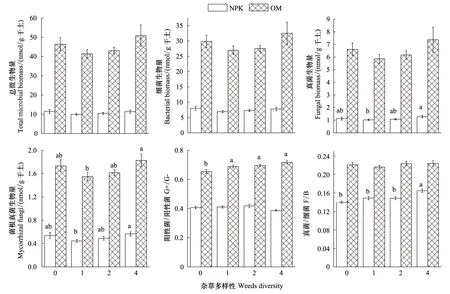

由图1可知:在施有机肥处理中,土壤总微生物量和各类群微生物量远高于施化肥处理;在施有机肥各个杂草多样性处理中,总微生物量是施化肥各个杂草多样性处理的4.0、4.2、4.1、4.5倍;施有机肥处理中阳性菌和阴性菌比、真菌和细菌比高于施化肥处理。

表3 施肥和杂草多样性处理下初级生产量(g/ 盆)

数据为平均值±标准误,0种和4种杂草处理重复6次,1种和2种杂草处理重复12次

在施化肥处理中,杂草多样性对总微生物量、细菌生物量无显著影响;真菌和菌根真菌生物量在1种杂草处理中最低(1.0 nmol/ g干土和0.4 nmol/ g干土),在4种杂草处理中最高(1.3 nmol/ g干土和0.6 nmol/ g干土),且两处理间有显著性差异,其他处理之间无显著差异;阳性菌和阴性菌比在各处理间无显著差异;真菌和细菌比在0种杂草处理中最低,4种杂草处理中最高,且与0种杂草、1种杂草和2种杂草处理有显著性差异。

在施有机肥处理中,杂草多样性对总微生物量、细菌生物量、真菌生物量无显著影响;菌根真菌生物量在1种杂草处理中最低,为1.5 nmol/ g干土;在4种杂草处理中最高,为1.8 nmol/ g干土,且两处理间有显著性差异;阳性菌和阴性菌比在0种杂草处理中最低,在4种杂草处理中最高,0种杂草处理与有杂草处理间都有显著差异;真菌和细菌比在各杂草处理间无显著性差异。

表4 不同杂草多样处理间土壤微生物量和群落比的方差分析

图1 施肥和杂草多样性处理对土壤微生物量的影响Fig.1 Effects of fertilization and weeds diversity on microbial biomass at anthesis stage of winter wheatG+/ G-: Gram-positive bacteria biomass/Gram-negative bacteria biomass; F/ B: Fungi biomass/ bacterial biomass

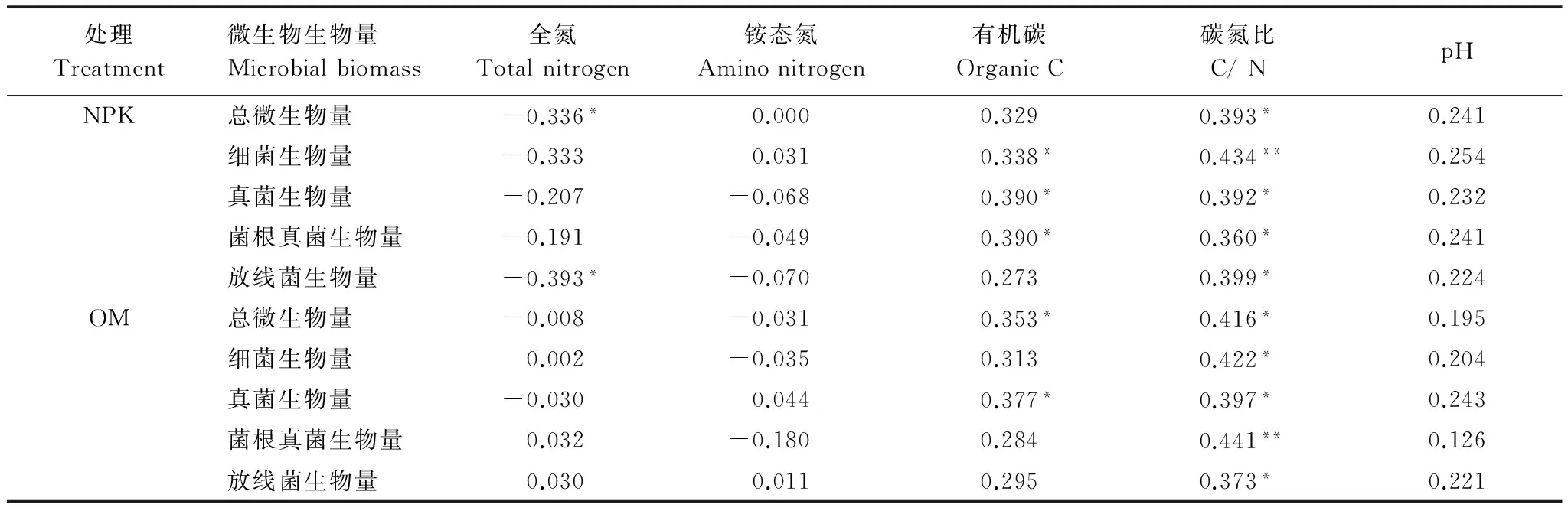

3.4 相关分析

由表5可知:在两个施肥处理中,碳氮比与总微生物量和各类群微生物量显著相关,铵态氮和pH值与微生物量无显著相关性。在施化肥处理中,有机碳与细菌、真菌、菌根真菌生物量显著相关;而在施有机肥处理中,有机碳与总微生物量和真菌生物量显著相关。

表5 微生物量与土壤化学性质相关分析

3.5 杂草物种对土壤微生物群落的影响

由表6可知:对含1种杂草处理进行方差分析,结果表明物种专一性对各类群土壤微生物量和类群比无显著影响。

4 讨论

施有机肥提高了土壤养分,更有利于增加土壤微生物量。结果表明施有机肥处理土壤总微生物量和各类群微生物量多于施化肥处理 (图1),因为有机肥处理中有机碳含量高于施化肥处理(表2),微生物量依赖于土壤有机碳[27];有机肥本身含有微生物,这也是增加土壤微生物量的原因。施肥显著改变了土壤微生物群落结构,施化肥处理中阳性菌与阴性菌比低于施有机肥 (图1)。Marschner 等[28]在长期施肥研究中结果也表明阳性菌与阴性菌比在施化肥处理中显著低于施有机肥处理。施有机肥处理有较高的真菌和细菌比 (图1),增加真菌和细菌比被认为增强了生态系统效率和食物网复杂性[29-30]。是农田生态系统更加可持续发展的标志并且对环境有较低的影响[31]。而且,施有机肥处理碳氮比高于施化肥处理(表2),碳氮比在一定范围内可以作为养分肥力的指标。因此,施有机肥更有利于土壤生态系统稳定性。

杂草多样性显著改变了土壤养分,在两个施肥处理中,4种杂草多样性处理中碳氮比和pH值最高(表2)。碳氮比和pH值是重要的环境因子,会影响微生物群落构成,尽管在施有机肥4种杂草处理中pH值有显著增加(表2),但pH值变化范围比较窄,且与各类群微生物量无显著相关(表5),而各类群微生物量和与碳氮比显著相关(表5),所以增加杂草多样性通过改变土壤碳氮比改变微生物群落结构,证明了第一个假设。这和Marschner等[28]研究结果相同,细菌和真菌群落结构显著地受碳氮比影响。

大部分土壤微生物是依赖外源碳的非自养生物,根代谢物增加了土壤有机碳,有利于微生物生长。本文结果表明地上杂草多样性和地下微生物群落紧密相关(表4)。在施化肥处理中,杂草多样性显著影响真菌和细菌比(表4),4种杂草处理中,真菌和细菌比最高(图1),因为在4种杂草处理中真菌生物量最多(图1)。真菌能分解大量的植物残体释放营养,促进土壤团聚提高土壤质量,且能增加土壤碳储存。因此,在施化肥处理中物种丰富的植物群落的生态位互补作用、积极的交互作用和较多的可利用资源[32-33]更有利于真菌生长。4种杂草处理增强了生态系统效率的另一个原因是菌根真菌生物量最大,菌根真菌能增强宿主对氮和磷的吸收,也可以减少宿主土传病虫害[34];而且4种杂草处理中有较多的原生动物和小型节肢动物(未发表),土壤动物与微生物交互作用刺激分解作用[35-36],提高作物对土壤中氮的吸收并且减少害虫的危害[37-38]。因此,施化肥处理中增加杂草多样性通过改变真菌和细菌比影响微生物群落,并且有助于改善土壤生态系统。在施有机肥处理中,杂草多样性显著影响阳性菌和阴性菌比(表4),阴性菌生物量在4种杂草处理中最高。阴性菌倾向于利用根围来源的碳[39],大量的阴性菌被认为是从贫营养到富营养的转变[40]。植物通过改变根分泌液质量和数量影响阴性菌生物量,因为根分泌液是微生物利用的重要碳源,而且根分泌液和沉积物可以刺激微生物生长[41]。在有机肥处理中,杂草多样性对真菌和细菌比无显著影响(表4),因此,在有机肥处理中增加杂草多样性对改善土壤生态系作用不大,可能因为在肥沃和生物学健康的土壤中,杂草处于竞争弱势地位。在两种施肥处理中增加杂草多样性改变微生物群落结构的方式不同。证明了第二个假设。因此,植物物种丰富度是影响微生物交互的重要因子。尽管在杂草多样性处理间微生物群落结构差别较小,但这些微小差别对微生物驱动的生态系统过程(如营养循环)会有重要的积累效应。

Milcu等[42]研究表明豆科物种的存在对土壤微生物量有积极的作用。实验中,却没有得出此结论,在含有豆科、菊科、禾本科和十字花科杂草物种处理中,物种专一性对土壤微生物量和类群比都无显著影响(表6)。因此,是物种多样性而不是物种专一性影响微生物群落构成。Eisenhauer等[43]研究结果也表明是植物多样性而不是植物功能组驱动土壤食物网的结构和功能。建议在农田中施有机肥,以增加土壤微生物量;在施化肥农田中要保持一定的杂草多样性,用于调节土壤微生物群落结构,改善土壤生态系统。

5 结论

本文结果显示施有机肥能较大的增加土壤微生物量和增加土壤养分。杂草多样性通过改变土壤碳氮比显著影响微生物群落构成,施化肥处理中增加杂草多样性显著增加了真菌和细菌比和土壤碳氮比,提高了土壤生态系统稳定性;而在肥沃的有机肥处理中,增加杂草多样性显著增加了阳性菌和阴性菌比、pH值。

[1] Chakraborty A, Chakrabarti K, Chakraborty A, Ghosh S. Effect of long-term fertilizers and manure application on microbial biomass and microbial activity of a tropical agricultural soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2011, 47(2): 227-233.

[2] Chapin III F S, Zavaleta E S, Eviner V T, Naylor R L, Vitousek P M, Reynolds H L, Hooper D U, Lavorel S, Sala O E, Hobbie S E, Mack M C, Diaz S. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature, 2000, 405(6783): 234-242.

[3] Li H, Wang C, Li X L, Christie P, Dou Z X, Zhang J L, Xiang D. Impact of the earthwormAporrectodeatrapezoidsand the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungusGlomusintraradiceson15N uptake by maize from wheat straw. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2013, 49(3): 263-271.

[4] Snyder C S, Bruulsema T W, Jensen T L, Fixen P E. Review of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production systems and fertilizer management effects. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 2009, 133(3/4): 247-266.

[5] Ramirez K S, Lauber C L, Knight R, Bradford M A, Fierer N. Consistent effects of nitrogen fertilization on soil bacterial communities in contrasting systems. Ecology, 2010, 91(12): 3463-3470.

[6] Chen X P, Cui Z L, Vitousek P M, Cassman K G, Matson P A, Bai J S, Meng Q F, Hou P, Yue S C, Romheld V, Zhang F S. Integrated soil-crop system management for food security. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(16): 6399-6404.

[7] Demoling F, Nilsson L O, Bååth E. Bacterial and fungal response to nitrogen fertilization in three coniferous forest soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2008, 40(2): 370-379.

[8] Zhong W H, Gu T, Wang W, Zhang B, Lin X G, Huang Q R, Shen W S. The effects of mineral fertilizer and organic manure on soil microbial community and diversity. Plant and Soil, 2010, 326(1/2): 511-522.

[9] Chu H Y, Fujii T, Morimoto S, Lin X G, Yagi K, Hu J L, Zhang J B. Community structure of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria under long-term application of mineral fertilizer and organic manure in a sandy loam soil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73(2): 485-491.

[10] Liu L, Gundersen P, Zhang T, Mo J M. Effects of phosphorus addition on soil microbial biomass and community composition in three forest types in tropical China. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2012, 44(1): 31-38.

[11] Gibson R H, Nelson I L, Hopkins G W, Hamlett B J, Memmott J. Pollinator webs, plant communities and the conservation of rare plants: arable weeds as a case study. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2006, 43(2): 246-257.

[12] Marshall E J P, Brown V K, Boatman N D, Lutman P J W, Squire G R, Ward L K. The role of weeds in supporting biological diversity within crop fields. Weed Research, 2003, 43(2): 77-89.

[13] Loreau M, Naeem S, Inchausti P, Bengtsson J, Grime J P, Hector A, Hooper D U, Huston M A, Raffaelli D, Schmid B, Tilman D, Wardle D A. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. Science, 2001, 294(5543): 804-808.

[14] Wardle D A, Bardgett R D, Klironomos J N, Setälä H, van der Putten W H, Wall D H. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science, 2004, 304(5677): 1629-1633.

[15] Wortman S E, Drijber R A, Francis C A, Lindquist J L. Arable weeds, cover crops, and tillage drive soil microbial community composition in organic cropping systems. Applied Soil Ecology, 2013, 72: 232-241.

[16] Batten K M, Scow K M, Davies K F, Harrison S P. Two invasive plants alter soil microbial community composition in serpentine Grasslands. Biological Invasions, 2006, 8(2): 217-230.

[17] Corneo P E, Pellegrini A, Cappellin L, Gessler C, Pertot I. Weeds influence soil bacterial and fungal communities. Plant and Soil, 2013, 373(1/2): 107-123.

[18] Van Der Heijden M G A, Bardgett R D, Van Straalen N M. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecology Letters, 2008, 11(3): 296-310.

[19] He Y, Ding N, Shi J C, Wu M, Liao H, Xu J M. Profiling of microbial PLFAs: implications for interspecific interactions due to intercropping which increase phosphorus uptake in phosphorus limited acidic soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2013, 57: 625-634.

[20] Bellinger B J, Hagerthey S E, Newman S, Cook M I. Detrital floc and surface soil microbial biomarker responses to active management of the nutrient impacted florida everglades. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 64(4): 893-908.

[21] Loreau M, Mouquet N, Gonzalez A. Biodiversity as spatial insurance in heterogeneous landscapes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2003, 100(22): 12765-12770.

[22] Wang J H, Hu J L, Lin X G, Cui X C, Dai J, Yin R, Qin S W. Changes in soil microbial activities and nutrient uptake of wheat in response to fertilization regimes in a long-term field experiment. Chinese Journal of Soil Science, 2010, 41(4): 807-810.

[23] Bossio D A, Scow K M. Impacts of carbon and flooding on soil microbial communities: phospholipid fatty acid profiles and substrate utilization patterns. Microbial Ecology, 1998, 35(3/4): 265-278.

[24] Bartelt-Ryser J, Joshi J, Schmid B, Brandl H, Balser T. Soil feedbacks of plant diversity on soil microbial communities and subsequent plant growth. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 2005, 7(1): 27-49.

[22] 王俊华, 胡君利, 林先贵, 崔向超, 戴珏, 尹睿, 钦绳武. 长期定位施肥对潮土微生物活性和小麦养分吸收的影响.土壤通报, 2010, 41(4): 807-810.

[26] Bååth E. The use of neutral lipid fatty acids to indicate the physiological conditions of soil fungi. Microbial Ecology, 2003, 45(4): 373-383.

[27] Denef K, Roobroeck D, Manimel Wadu M C W, Lootens P, Boeckx P. Microbial community composition and rhizodeposit-carbon assimilation in differently managed temperate grassland soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2009, 41(1): 144-153.

[28] Marschner P, Kandeler E, Marschner B. Structure and function of the soil microbial community in a long-term fertilizer experiment. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2003, 35(3): 453-461.

[29] Sakamoto K, Oba Y. Effect of fungal to bacterial biomass ratio on the relationship between CO2 evolution and total soil microbial biomass. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 1994, 17(1): 39-44.

[30] Wardle D A, Yeates G W, Watson R N, Nicholson K S. The detritus food-web and the diversity of soil fauna as indicators of disturbance regimes in agro-ecosystems. The Significance and Regulation of Soil Biodiversity, 1995, 63: 35-43.

[31] de Vries F T, Hoffland E, Eekeren N V, Brussaard L, Bloem J. Fungal/bacterial ratios in grasslands with contrasting nitrogen management. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2006, 38(8): 2092-2103.

[32] Tilman D, Reich P B, Knops J, Wedin D, Mielke T, Lehman C. Diversity and productivity in a long-term grassland experiment. Science, 2001, 294(5543): 843-845.

[33] Chung H, Zak D R, Reich P B, Ellsworth D S. Plant species richness, elevated CO2, and atmospheric nitrogen deposition alter soil microbial community composition and function. Global Change Biology, 2007, 13(5): 980-989.

[34] Schnitzer S A, Klironomos J N, HillerisLambers J, Kinkel L L, Reich P B, Xiao K, Rillig M C, Sikes B A, Callaway R M, Mangan S A, van Nes E H, Scheffer M. Soil microbes drive the classic plant diversity-productivity pattern. Ecology, 2011, 92(2): 296-303.

[35] Yang X D, Chen J. Plant litter quality influences the contribution of soil fauna to litter decomposition in humid tropical forests, southwestern China. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2009, 41(5): 910-918.

[36] Wall D H, Bradford M A, John M G S, Trofymow J A, Benhan-Pelletier V, Bignell D E, Dangerfield J M, Parton W J, Rusek J, Voigt W, Wolters V, Gardel H Z, Ayuke F O, Bashford R, Beljakova O, Bohlen P J, Baruman A, Fiemming S, Henschel J R, Johnson D, Jones T H, Kovarova M, Kranabetter J M, Kutny L, Lin K C, Maryati M, Masse D, Pokarzhevskii A, Rahman H, Sabara M G, Salamon J A, Swift M J, Varela A, Vasconcelos H, White D, Zou X M. Global decomposition experiment shows soil animal impacts on decomposition are climate-dependent. Global Change Biology, 2008, 14(11): 2661-2677.

[37] Eisenhauer N, Milcu A, Sabais ACW, Scheu S. Animal ecosystem engineers modulate the diversity invasibility relationship. PLoS ONE, 2008, 3(10): e3489.

[38] Ke X, Scheu S. Earthworms, Collembola and residue management change wheat (Triticumaestivum) and herbivore pest performance (Aphidina:Rhophalosiphumpadi). Oecologia, 2008, 157(4): 603-617.

[39] Schutter M E, Dick R P. Microbial community profiles and activities among aggregates of winter fallow and cover-cropped soil. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2002, 66(1): 142-153.

[40] Saetre P, Bååth E. Spatial variation and patterns of soil microbial community structure in a mixed spruce-birch stand. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2000, 32(7): 909-917.

[41] Rodríguez H, Fraga R, Gonzalez T, Bashan Y. Genetics of phosphate solubilization and its potential applications for improving plant growth-promoting bacteria // First International Meeting on Microbial Phosphate Solubilization Developments in Plant and Soil Sciences. Netherlands: Springer, 2007: 15-21.

[42] Milcu A, Partsch S, Scherber C, Weisser W W, Scheu S. Earthworms and legumes control litter decomposition in a plant diversity gradient. Ecology, 2008, 89(7): 1872-1882.

[43] Eisenhauer N, Dobies T, Cesarz S, Hobbie S E, Meyer R J, Worm K, Reich P B. Plant diversity effects on soil food webs are stronger than those of elevated CO2and N deposition in a long-term grassland experiment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(17): 6889-6894.

Effects of fertilization and diversity of weed species on the soil microbial community

SUN Feng1, ZHAO Cancan1, HE Qiongjie1, LÜ Huihui1, GUAN Yixin1, GU Yanfang1,2,*

1CollegeofLifescience,HenanUniversity,Kaifeng475004,China2InstituteofEcologicalScienceandTechnology,HenanUniversity,Kaifeng475004,China

Farmland ecosystems are primary producers of food, feed, fiber, and other natural products. Species diversity constitutes an important foundation in farmland ecosystems, but human activities are greatly accelerating the loss rate of species. Considerable evidence shows that agricultural management threatens biodiversity and negatively affects species richness and abundance of taxa. In major grain-producing areas, reductions in productivity and soil biodiversity and serious pollution problems occur as a result of fertilizer and pesticide use as well as new agricultural technologies. Conservation of biological diversity is considered to be an important strategy to reduce risks to agriculture in the future. Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis was employed to examine the effects of fertilization and diversity of weed species on soil microbial community structure in a winter wheat plantation. The experiment used a split-plot design and was established in October 2010. Two fertilization treatments (including chemical fertilizer and organic manure) were applied to the main plots and diversity of weed species (0, 1, 2 and 4 species) were sown in the sub-plots. Wheat was grown in the center of plots and weeds were grown around the wheat plants (all eight plants). The weed species wereAvenafatua,Medicagosativa,Cichoriumintybus, andDescurainiasophia. For the zero species weed treatments, six plots were grown of wheat plants only. For the 1-species weed treatments, one kind of weed was grown with the wheat in 12 plots. For the 2-species weed treatments, two weed species were grown with the wheat in 12 plots. For the 4-species weed treatments, four weed species were grown with the wheat in six plots. Increased weed diversity significantly increased the soil carbon(C)∶nitrogen(N) ratio and pH in both fertilizer treatments, and the C∶N ratio was the highest in the 4-species treatment. In the chemical fertilizer treatment, weed diversity significantly affected the fungi:bacteria ratio, which was highest in the 4-species treatment. Fungal and mycorrhizal fungal biomass were lowest in the 1-species treatment (1.0 nmol/g dry soil and 0.4 nmol/g dry soil, respectively), and significantly lower than in the 4-species treatment (1.3 nmol/g dry soil and 0.6 nmol/g dry soil, respectively). In the organic manure treatments, the gram-positive:gram-negative bacterial ratio was lowest in the 0-species treatment compared with the 1-, 2-and 4-species treatments. Mycorrhizal fungal biomass was lowest in the 1-species treatment (1.5 nmol/g dry soil), and significantly lower than in the 4-species treatment (1.8 nmol/g dry soil). In both fertilizer treatments, weed species diversity affected microbial community composition by changing the soil C∶N ratio, which was correlated with biomass of various functional groups of soil microbes. Moreover, the shift of the microbial community composition in a different way. Plant species richness is an important factor affecting microbial interactions. Despite the small differences in microbial community structure between different weed diversity treatments, these minor differences will have an important cumulative effect on microbial-driven ecosystem processes. For legumes,Asteraceae,Poaceae, and cruciferous weed species treatments, species specificity had no significant effects on soil microbial biomass and taxa. Thus, species diversity affects microbial community composition. We recommend applying manure to increase soil microbial biomass in farmlands and maintain diversity of weed species. This will lead to changes in microbial community structure to regulate and improve soil ecosystem stability in chemically fertilized farmland. This study is of practical and theoretical significance for 1) our understanding of how plant diversity affects soil microbial community composition and the development of soil ecosystem health, 2) exploring microbial ecological function in maintaining soil ecosystem stability, and 3) revealing plant-soil-microbial interactions and feedback mechanisms.

PLFA; fertilization; weed diversity; main crop

国家自然科学基金项目(31070394); 河南省科技攻关项目(142102110034)

2014-01-09;

日期:2014-11-19

10.5846/stxb201401090071

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: guyanfang@henu.edu.cn

孙锋, 赵灿灿, 何琼杰, 吕会会, 管奕欣, 谷艳芳.施肥和杂草多样性对土壤微生物群落的影响.生态学报,2015,35(18):6023-6031.

Sun F, Zhao C C, He Q J, Lü H H, Guan Y X, Gu Y F.Effects of fertilization and diversity of weed species on the soil microbial community.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2015,35(18):6023-6031.