海洋浮游纤毛虫生长率研究进展

2014-05-05张武昌李海波丰美萍

张武昌 ,李海波,丰美萍,陈 雪,于 莹,赵 苑,肖 天

(1.中国科学院海洋研究所,海洋生态与环境科学重点实验室,青岛 266071;2.中国科学院大学,北京 100049)

海洋浮游纤毛虫是一类具纤毛并营浮游生活的单细胞原生动物,属于纤毛门(Ciliophora),多数属于旋毛纲(Spirotrichea)下的寡毛亚纲(Oligotrichia)及环毛亚纲(Choreotrichia)。浮游纤毛虫的粒级在10—200 μm之间,根据壳的有无分为具壳的砂壳类(900余种)和无壳类(约150种),它们在自然水体中的丰度约为1000个/L,在大多数情况下,无壳纤毛虫的丰度较高。

浮游纤毛虫与异养腰鞭毛虫(dinoflagellates)和鞭毛虫(flagellates)同属于海洋浮游生态系统粒级划分的微型浮游动物(microzooplankton),是海洋浮游食物网的重要组成部分[1],它们摄食pico和nano级浮游生物,同时被中型浮游动物(mesozooplankton)摄食,所以浮游纤毛虫是联系微食物网和经典食物链的重要环节。同浮游植物相比,纤毛虫具有较高的营养价值,颗粒粒径较大,在桡足类饵料中占的比例较大。

浮游纤毛虫生长率是估计纤毛虫生产力的重要参数。同浮游植物初级生产和中型浮游动物次级生产是浮游生态学研究的重要内容一样,浮游纤毛虫的次级生产也是海洋浮游生态学研究的重要内容。浮游纤毛虫生长率是理解其种群动力学的重要参数。浮游纤毛虫的丰度和生物量是纤毛虫生长和死亡共同作用的结果,无法反映出种群动态变化的机制。生长率是评价纤毛虫种群受上行控制(饵料不足)和下行控制(摄食压力过大)影响的重要参考指标。

目前国外在实验室内(自 Heinbokel[2]开始)和海上现场(自Capriulo[3]开始)都对浮游纤毛虫的生长率进行了研究,国内在这方面研究还比较少,实验室内对浮游纤毛虫生长率的研究只有类彦立等[4],海上现场生长率的研究还未涉及。目前已经在我国海区积累了一些浮游纤毛虫丰度和生物量的资料,纤毛虫现场生长率的研究是我国微型浮游动物生态学亟需进行的内容之一,本文综述了海洋浮游纤毛虫生长率和生产力的研究历史和现状,为我国浮游纤毛虫生长的研究提供借鉴。

1 室内浮游纤毛虫生长率的研究方法

测定纤毛虫生长率的方法,都是将一定丰度的纤毛虫放入含有饵料(不同种类、种类组合或自然饵料)的培养液中培养一段时间t(d),估计培养前(C0)和培养后(Ct)培养液中纤毛虫的丰度,假设纤毛虫的生长为指数生长,生长率(μ,d-1或 h-1)按照公式μ=ln(Ct/C0)/t计算得出。

上述纤毛虫的生长率是根据纤毛虫丰度变化来计算,这样做的前提是假设所有纤毛虫的体积是一样的。但是纤毛虫的体积在不同的营养状况下会有变动。Montagnes 和 Lessard[5]报 道 Strombidinopsis multitauris在饵料充足时的体积是饥饿时体积的2倍。而 Fenchel和 Jonsson[6]报道 Strombidium sulcatum的体积变化可达 8倍。Ohman和 Snyder[7]报道Strombidium sp.在指数生长期的细胞体积小一些,在稳定期细胞体积增大,变化达2倍。兼性自养的种类Laboea strobila和Strombidium conicum在不同的光照下体积变化可达2倍[8-9]。温度也可能影响细胞的 体 积,例 如 Montagnes 和 Lessard[5]报 道Strombidinopsis multitauris体积在10℃最大,在5—10℃细胞体积随温度升高而变大,在10—22℃细胞体积随温度升高而变小。因此纤毛虫生长率的这个计算方法也有不足之处。

2 室内浮游纤毛虫生长率研究的结果

2.1 饵料浓度对纤毛虫生长率的影响

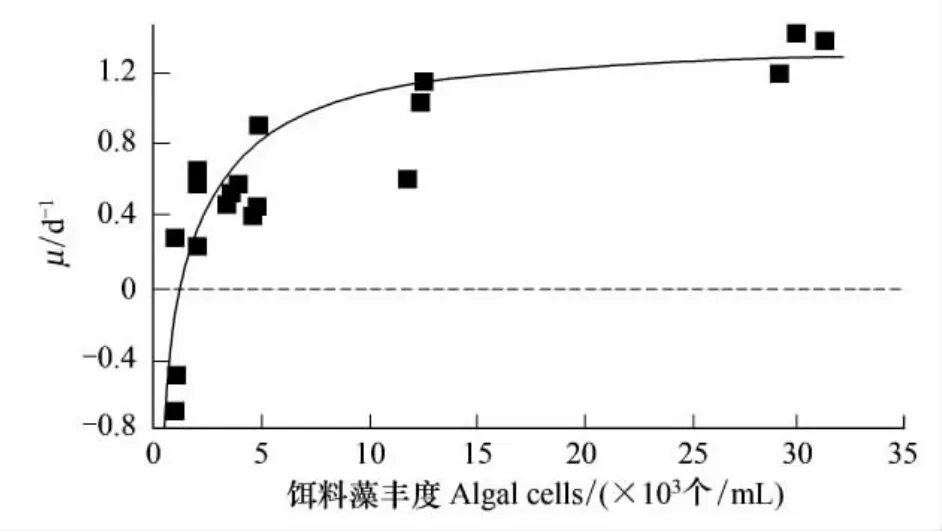

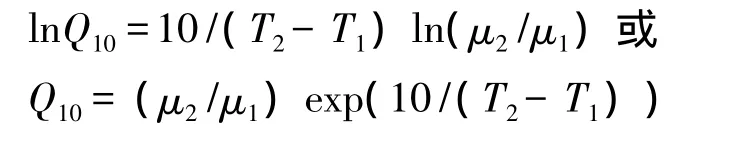

对于特定的纤毛虫种类,在一定的温度下,其生长率与饵料浓度的关系叫数值反应。Heinbokel[2]首先研究浮游寡毛类纤毛虫的数值反应,发现纤毛虫的生长率随饵料浓度的变化成双曲线型,在饵料浓度低时不生长,生长率随饵料浓度增加而增大,当饵料浓度达到和超过一定的数值时,随着饵料浓度的增加,生长率稳定在一定的水平或者有所下降,这时的生长率为内禀生长率(μmax)(图1)。

图1 纤毛虫Strobilidium spiralis生长率(μ)随饵料藻丰度的变化[10]Fig.1 Therelationship betweengrowth rate(μ)of Strobilidium spiralis and algal cells[10]

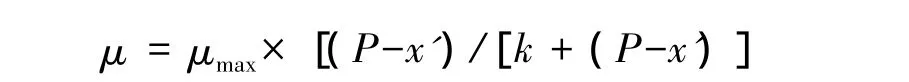

Montagnes[11]把特定温度下纤毛虫的生长率与饵料浓度的关系表示为:

式中,P是饵料的浓度,x'是生长阈值浓度,即生长率为零(不生长)时的饵料浓度,k是常数。当饵料浓度为x'+k时,纤毛虫的生长率为μmax/2。

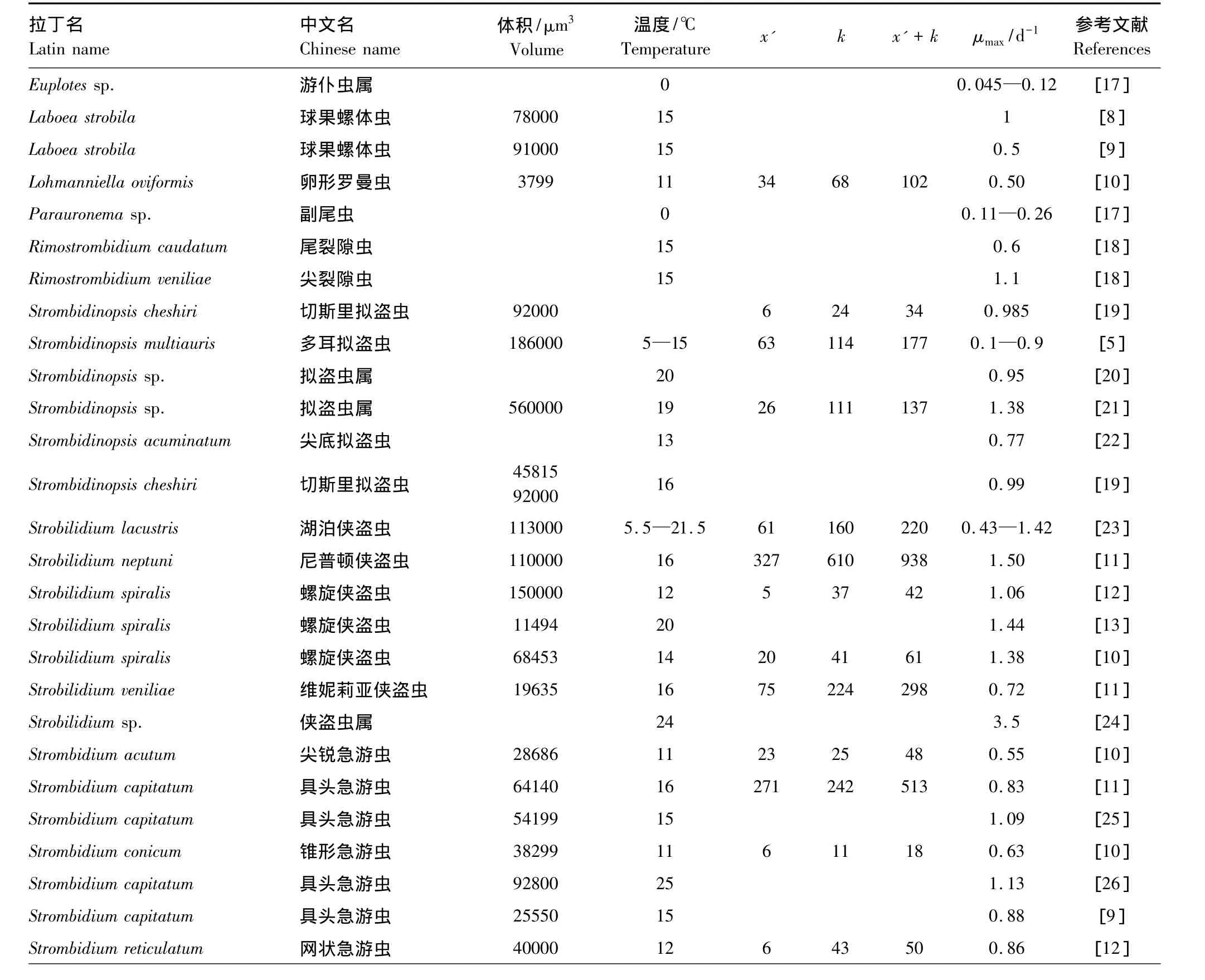

不同纤毛虫的生长阈值浓度不同,从最低6 μg C/L到327 μg C/L(表1)。浮游纤毛虫在饵料浓度低于生长阈值浓度时会死亡,但是死亡的时间各不相同。Fenchel和 Jonsson[6]发现 Strombidium sulcatum饥饿3.5 d 后有 90%的个体死亡,Montagnes[11]发现Strobilidium和Strombidium属的种类饥饿1—2 d内就会死亡。

除Strombidium siculum外,Strombidium属的内禀生长率范围较窄(0.8—1.1 d-1)。除了S.capitatum,大多数种类生长率达到μmax/2的饵料浓度低于50 μg C/L。Strobilidium属的种类生长率高一点,但是也更分散,为 0.7—1.7 d-1,除了 Strobilidium spiralis外,大多数种类生长率达到μmax/2的饵料浓度高于100 μg C/L。Strobilidium spiralis的饵料浓度阈值较低,为 42—61 μg C/L[10,12-13]。Strombidinopsis 属的数据不多,既有高的阈值,也有低的阈值,达到μmax/2的饵料浓度为34—177 μg C/L。个体较小的混合营养种Strombidium vestitum内禀生长率最高[10]。

表1 实验室内培养得出的无壳纤毛虫的内禀生长率(μmax)Table 1 Intrinsic growth rates of aloricate ciliates in laboratory(μmax)

续表

2.2 饵料种类对内禀生长率的影响

在相同的温度下,对于不同的饵料,纤毛虫的内禀生长率也不相同。因此内禀生长率常被用来指示饵料的营养价值、适口性[14-16]。

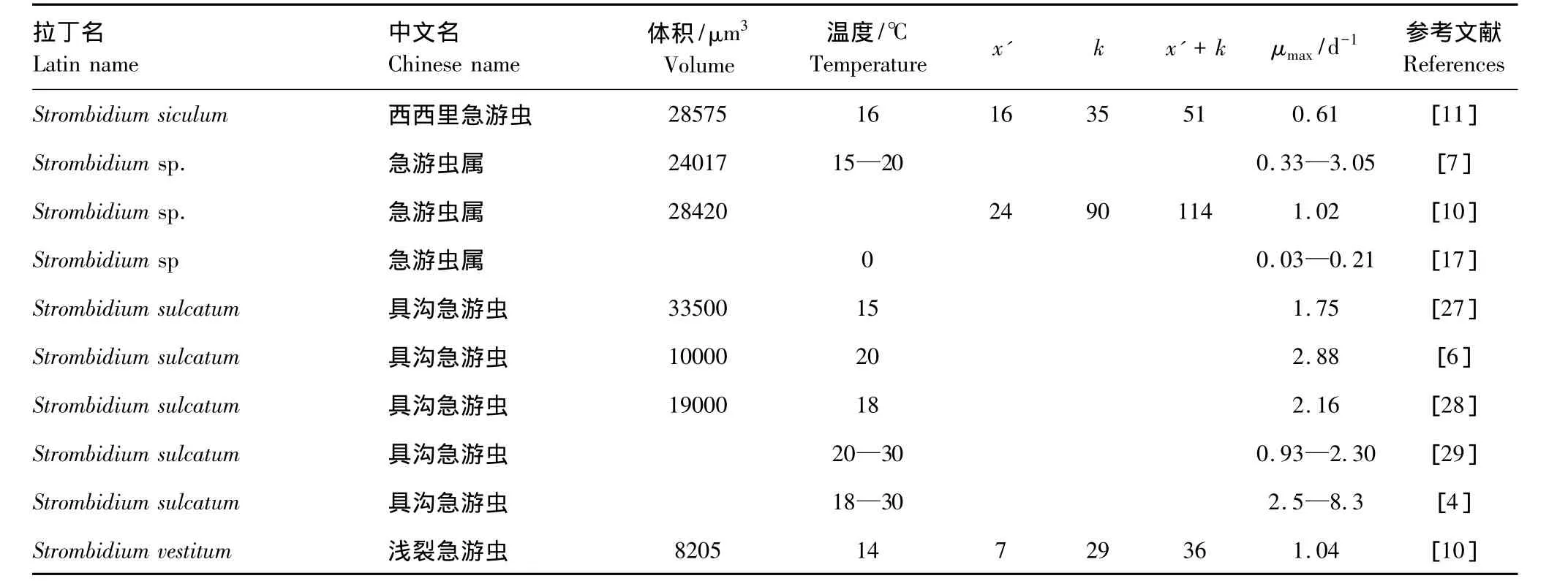

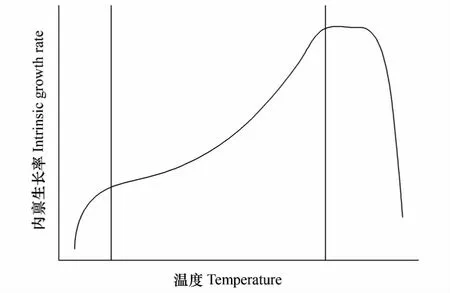

2.3 温度对内禀生长率的影响

对于同一种类而言,纤毛虫的内禀生长率与温度有关。在饵料适合时,不同温度下纤毛虫的内禀生长率随温度升高而升高,但是温度过高或过低对纤 毛 虫 也 有 抑 制 作 用 (图 2)[20]。 例 如Strombidinopsis multiauris在5℃会死亡,8.5—15℃时内禀生长率会从0.14—0.77 d-1线性增长,15—19℃时内禀生长率(约0.85 d-1)不再增加,22℃时内 禀 生 长 率 会 降 低 (0.13 d-1)[5]。Strombidium sulcatum在18℃时几乎不生长,在25℃时世代时间为 5.7 h,30 ℃时世代时间为 2 h[4]。

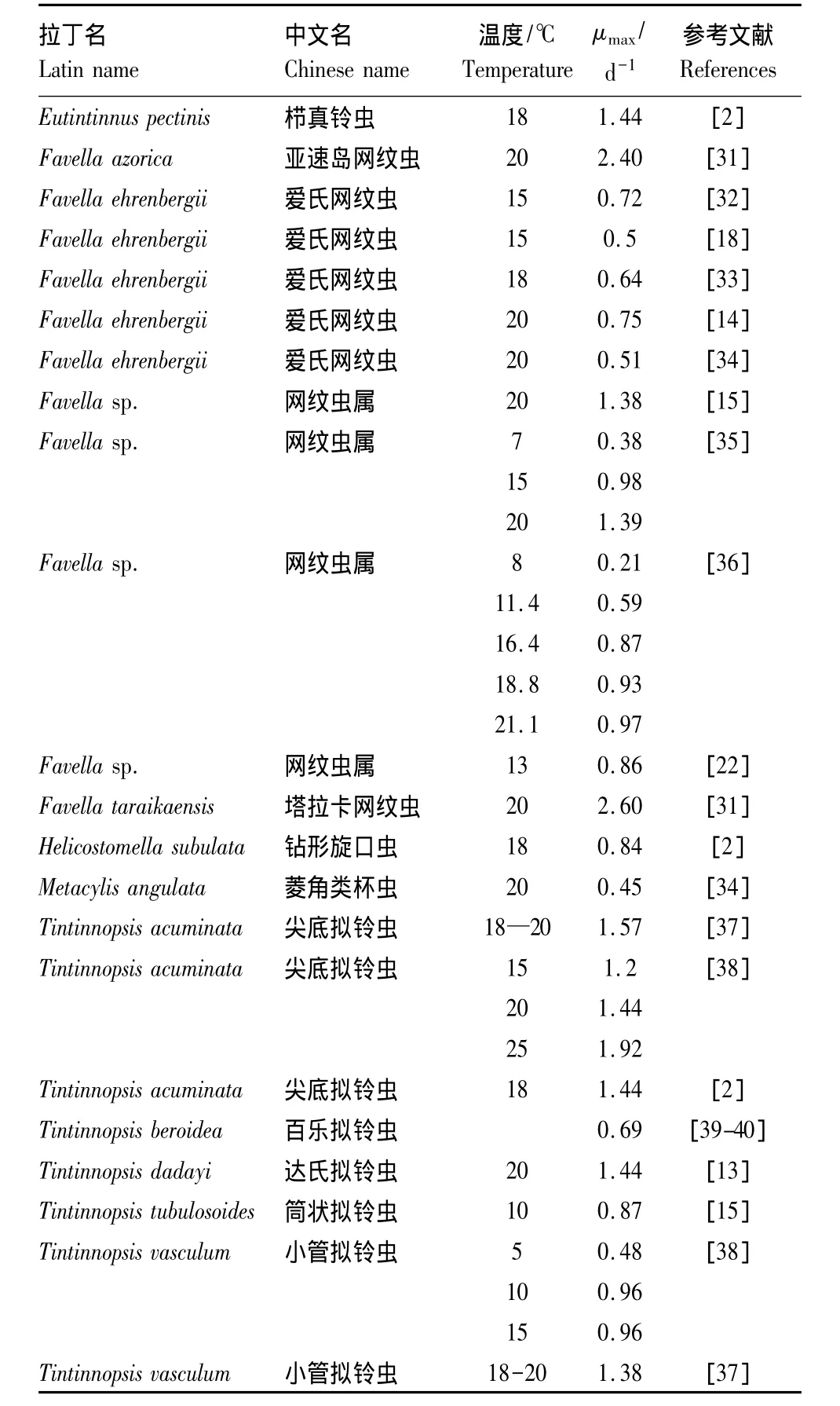

在实验室内测定过生长率的砂壳纤毛虫有12种(表2),温度范围为8—25℃,各种的内禀生长率变化范围为0.45—2.7 d-1。在实验室内测定过生长率的无壳纤毛虫有22种(表1),温度范围为5.5—30℃,除具沟急游虫的内禀生长率可达8.3 d-1外,其它各种的内禀生长率变化范围为0.1—3.5 d-1。

在内禀生长率随温度升高而升高的温度范围内,生长率随温度变化的关系可以用Q10来表示:

式中,μ2和μ1是温度T2和T1时的内禀生长率。

图2 纤毛虫内禀生长率与温度的关系图[30]Fig.2 Generalized description of the relationship between ciliates intrinsic growth rate and temperature[30]

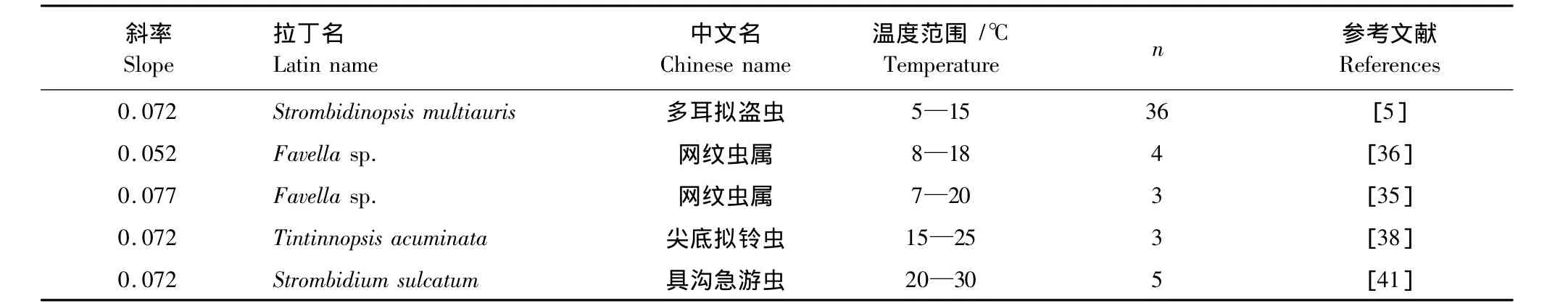

Montagnes等[30]分析了原生生物的内禀生长率和温度的关系,认为线性关系比Q10关系要好,平均的斜率为0.07。目前根据5种寡毛类纤毛虫的内禀生长率随温度升高而变化的资料计算得出内禀生长率随温度变化的斜率为 0.052—0.077(表 3)。Gismervik[10]利用 0.07 d-1℃-1的系数对寡毛类几个种的生长率进行转换成15℃的内禀生长率进行比较。

表2 实验室得出的砂壳纤毛虫的内禀生长率(μmax)Table 2 Intrinsic growth rates of tintinnids in laboratory(μmax)

2.4 pH对纤毛虫生长的影响

Pedersen和Hansen[18]使用室内实验检查pH值升高对几种纤毛虫(Favella ehrenbergii,Rimostrombidium caudatum,R.veniliae)生长的影响,当pH值升高到8.8—8.9时,生长率开始降低,pH值上升到8.9—9.0时,纤毛虫停止生长,当pH值上升到9.2—9.3时,纤毛虫快速死亡。

2.5 不同种类内禀生长率的差异

对于不同种类的无壳纤毛虫,其内禀生长率与个体大小有关,一般情况下,体长大的种类其内禀生长率较低。

但是也有报道体型较大的种类内禀生长率可能相当于或超过体型小的种类[10-11,42]。Montagnes[11]在实验室内测定几种寡毛类纤毛虫的内禀生长率,个体最大的种类(Strobilidium neptuni)内禀生长率最高。实验室内测定几种寡毛类纤毛虫的内禀生长率数据表明,个体最大的异养纤毛虫 Strobilidium spiralis的内禀生长率较高[10,12,43]。

Hansen 等[44]总结体长范围为 2—2000 μm 的浮游原生动物和浮游后生动物的生长率,发现随体长增加,生长率下降。但是对于浮游无壳纤毛虫这一类群而言,这个规律并不成立。

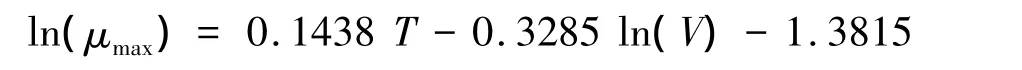

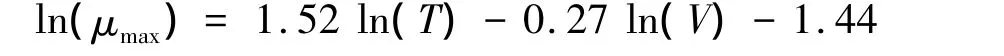

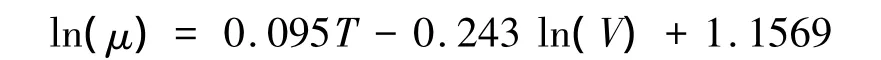

内禀生长率与体长和温度的关系可以用函数来表达。利用文献中实验室培养的结果,Montagnes等[45]得出纤毛虫内禀生长率(μmax)与温度(T)和个体体积大小(V)的关系为:

Müller和 Geller[23]则根据不同类群的资料总结了如下公式:

Perez 等[46]根 据 Nielsen 和 Kiorboe[47]的 公式ln(μmax)=a ln(T)+b ln(V)+c进一步给出了混合营养和异养纤毛虫内禀生长率与温度及体长间的不同系数。

表3 浮游寡毛类纤毛虫生长率和温度的关系Table 3 The relationship between growth rates of planktonic oligotrichous ciliates and temperature

Montagnes[11]认为现场的饵料水平无法判断是不是内禀生长率,所以只总结了当时已有实验室内的生长率资料,认为 Müller和 Geller[23]的公式最适合用来预测Strombilidium和Strombidium两个属的内禀生长率。

2.6 不同营养类型纤毛虫内禀生长率的差异

目前有关不同营养类型纤毛虫的内禀生长率有没有差异尚无定论。有的无壳纤毛虫是专性营养的,如Strombidium conicum需要进行光合作用,在黑暗中培养4 d以后的生长率会下降。所以在进行不同种类的生长率实验时要注意它们的食性[10]。Perez等[46]根据已有的文献中不同种类的生长率,用Montagnes[11]的公式总结了混合营养的种类和异养种类在内禀生长率上的差异,发现混合营养种类的生长率比相同体积的异养种类要低0.5 d-1,而Dolan和Perez[48]在海水的营养盐加富培养中发现自养和异养的纤毛虫的生长率都能够随饵料浓度的增加迅速增加到 1.2 d-1,Gismervik[10]也没有发现自养和异养纤毛虫在生长率方面的差异。

3 估计自然海区纤毛虫生长率的方法

自然海区纤毛虫生长率是自然界中的纤毛虫种群或群体在自然状况下(自然饵料、温度、光照和摇动)的生长率。要估计自然海区的生长率,可以用上述实验室的研究结果外推到自然界中[49-50],但是室内培养的结果与自然界的情况有很大不同,自然环境对生长率的影响在实验室内是很难模拟的[51],所以这种方法不是理想的方法。

其他方法有通过检测自然海区纤毛虫的分裂细胞频率(FDC,frequency-of-dividing-cells)来估计纤毛虫的生长率[52],也可以根据摄食率和毛生长效率(GGE)来估计生长率,例如Sherr等[53]估计如果西北地中海中粒级较小的纤毛虫(<15 μm)只吃细菌的话,生长率可以达到 0.5 d-1[47]。

估计自然海区纤毛虫生长率最好的方法是现场培养,首先使用这一方法的是Stoecker等[35],他们在1982年春天在Massachusetts的海边测量了几种纤毛虫的生长率。此后这种方法逐渐推广开来。

现场培养纤毛虫估计其生长率的方法主要是海水分粒级培养法[51,54],即将海水用一定孔径的筛绢过滤,假设过滤去除了纤毛虫所有的捕食者,将海水装入一定体积的培养瓶中在模拟的现场条件(水温、光照、摇动)下培养一段时间,根据培养前后纤毛虫丰度的变化计算生长率。

有关野外现场培养容器的选择上,人们经过了很长时间的探索。为了避免培养过程中的牢笼效应[55],人们使用了很多方法。为了使培养水体与外界进行交换,Stoecker等[35]使用了微型生物笼(体积400 mL),笼的两边有多孔(孔径12 μm)的膜,允许笼内的水与外面交换,Verity[54]和 Dolan[56]分别使用了2 L和0.6 L的透析袋。有的研究使用较大的培养体积,如 Gilron和 Lynn[51]使用了20 L的培养体积,Landry等[57]使用60 L的培养体积。但是后来大多使用2 L的培养瓶。

纤毛虫通过分裂方式进行无性繁殖,这种繁殖有没有昼夜节律还没有统一的结论,Heinbokel[52,58]认为有节律,而Verity[38]则认为没有节律。用培养的方法得出的是纤毛虫在一段时间内分裂的结果,所以培养实验最好超过1 d,实际上大多数培养的时间为1 d。

但根据现场培养实验来估算生长率的一个问题是经常得出负值,例如Verity等[59]稀释培养稀释度为零的一组中纤毛虫的生长率,3个实验中得出2个负值。Levinsen等[60]发现培养1 d后纤毛虫死亡很多。Fileman等[61]的实验中有一半的结果是负值。

由于纤毛虫非常脆弱,培养过程中对海水的转移、过滤等操作都可能造成纤毛虫死亡,所以对于出现负值的原因,很多作者很难确定是自然界的实际情况,还是操作造成的。

为减少实验操作对纤毛虫的影响,现在大多数培养中使用逆向过滤的方法,即将筛绢装在两端开口的圆筒的一端,将筛绢的一端浸入水中,开口的一端向上露出液面,将圆筒中的海水取出(虹吸或用容器如烧杯舀出)。但是这种操作本身对这些纤毛虫的影响也没有评估。

海水分粒级培养法假设过滤去除了纤毛虫的所有捕食者,但是,有些纤毛虫的捕食者(例如Didinium spp.和砂壳纤毛虫Favella sp.等其他捕食性的纤毛虫、异养甲藻和寄生甲藻)与纤毛虫处于同一粒级,甚至小于后者,所以不可避免的部分或全部通过了筛绢[47]。另外,实验室培养的纤毛虫在饵料不足时还出现自食现象[62],一些甲藻的分泌物能降低纤毛虫的生长率[15,33],这些现象在自然界也可能发生。因此海水分粒级培养法得出的生长率数据是保守估计。

4 现场纤毛虫生长率的研究结果

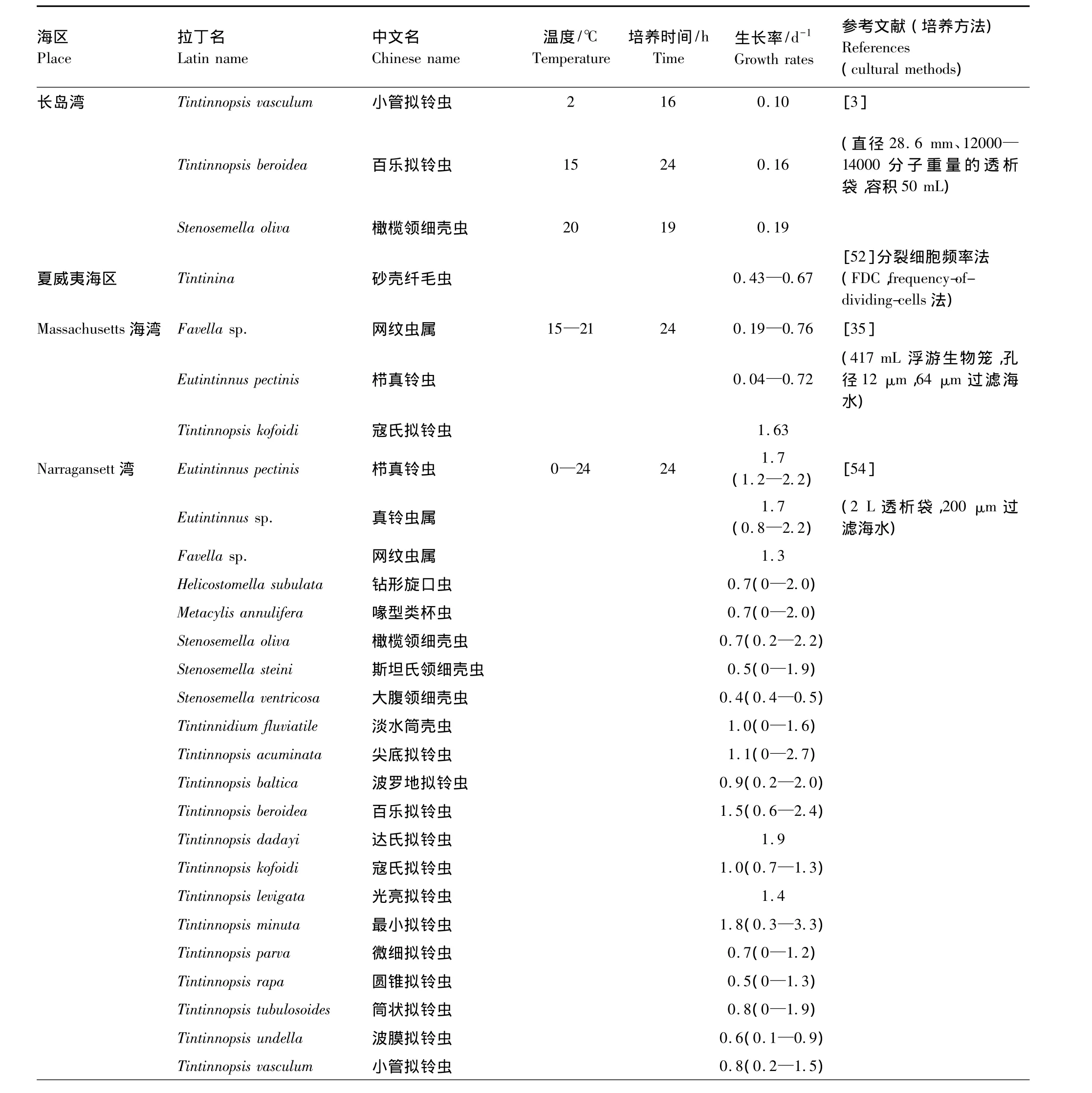

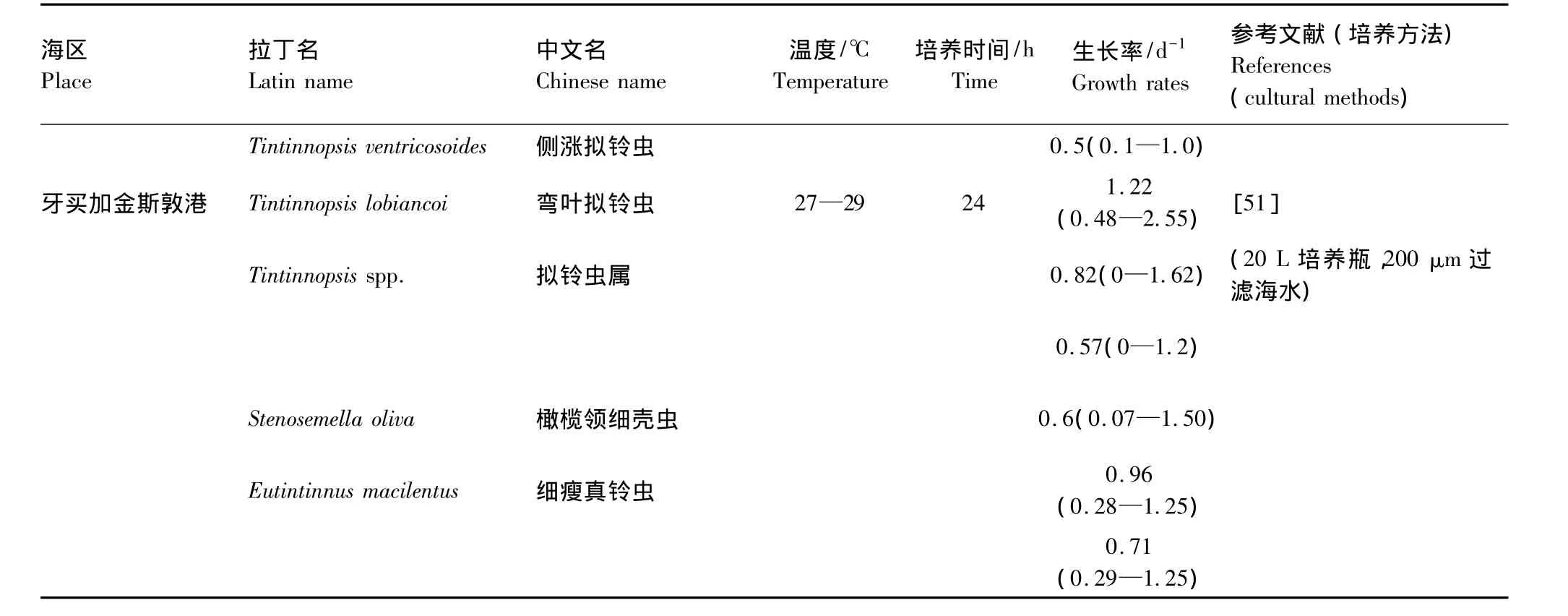

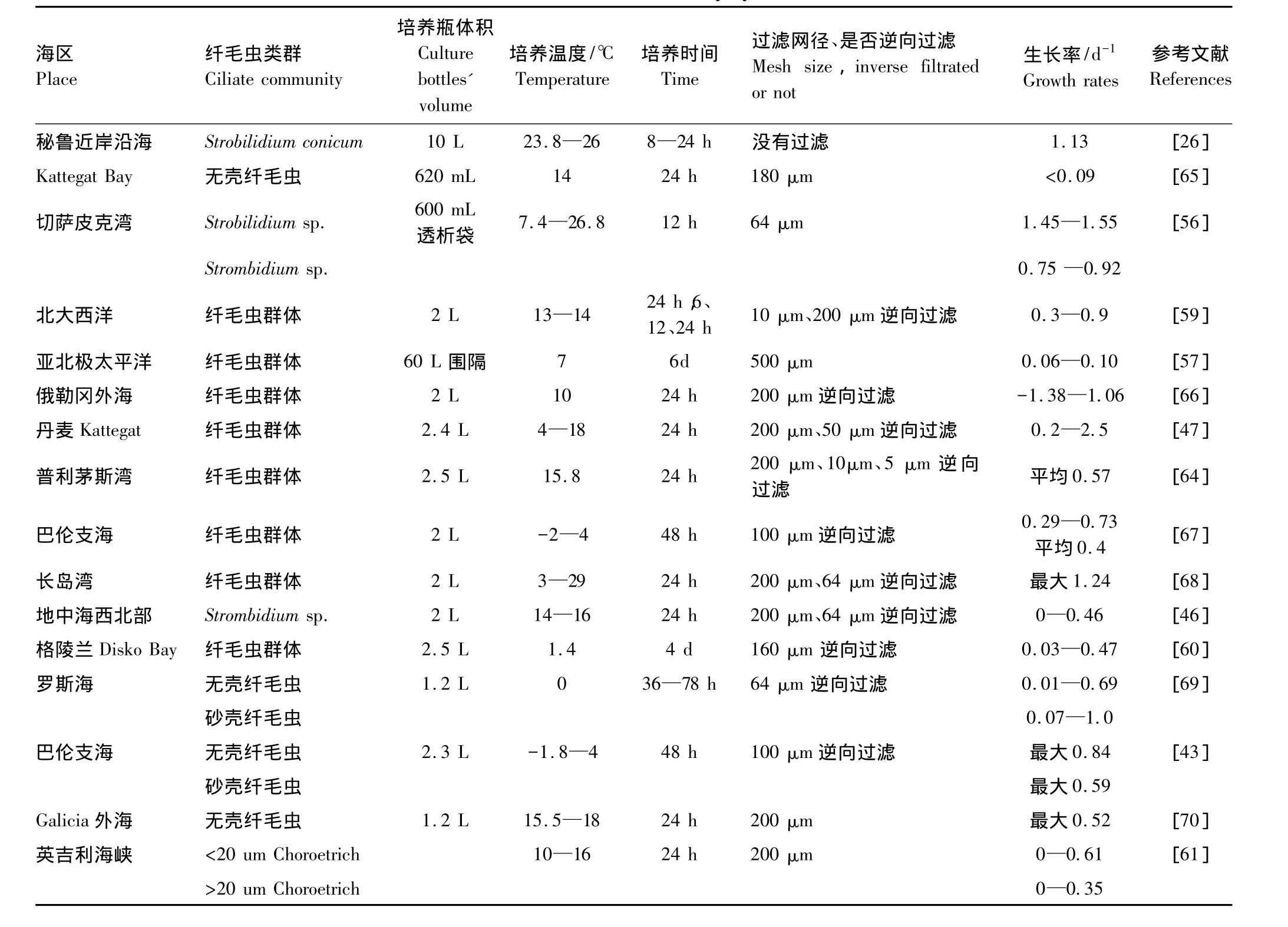

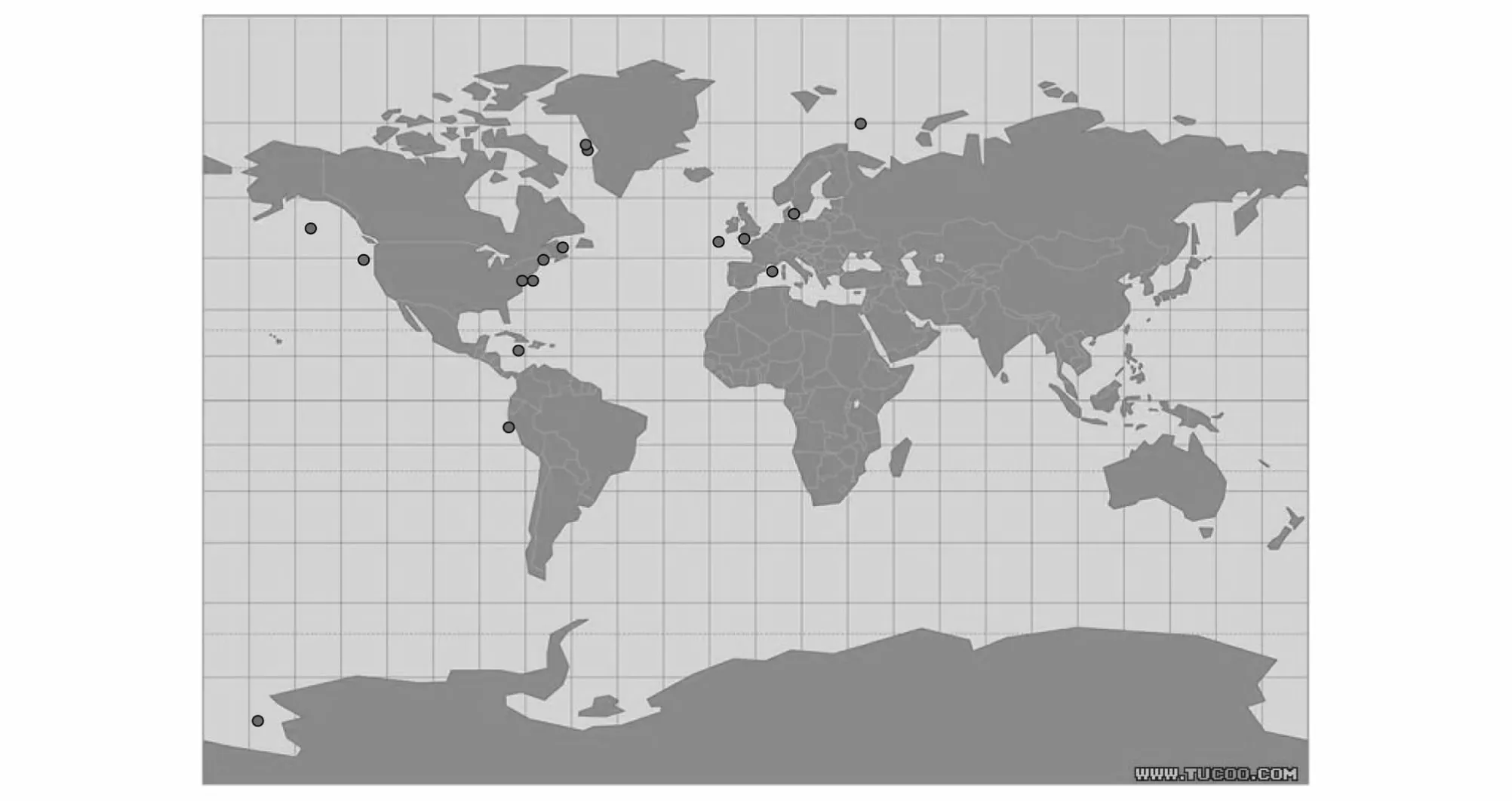

自 Stoecker 等[35]后,Tumantseva 和 Kopylov[26],Verity[54],Gilron 和 Lynn[51]及 Dolan[56]研究了几种纤毛虫(多为砂壳纤毛虫)的生长率(表4),因为这些研究不是针对纤毛虫群体的,所以 Sherr和Sherr[63]认为还没有有效的现场纤毛虫生长率的资料。1993年以后,纤毛虫群体的现场生长率测定得到重视,但是目前的文献较少26,43,47,50-70(表 5),研究海区主要在温带近岸区域(图3)。这些资料显示现场纤毛虫的生长率的最大值为3.3 d-1。

表4 不同海区现场培养得出的砂壳纤毛虫生长率Table 4 Growth rates of tintinnids by in situ incubations

续表

表5 不同海区现场培养得出的纤毛虫群落的生长率Table 5 Growth rates of ciliate community by in situ incubations

4.1 现场纤毛虫生长率结果与温度的关系

在现场的生长率同样得出生长率随温度升高而增加的趋势。Verity[54]在Narragansett Bay测定了20多种砂壳纤毛虫周年温度为0—25℃的生长率和温度的关系为 Q10=1.8。Dolan[56]在 Chesapeake Bay 4月、6月和8月得出以pico级浮游生物为食的纤毛虫群体的生长率在7.4—26.8℃生长率和温度的关系为 Q10=2。Nielsen 和 Kiorboe[47]在丹麦 Kattegat Bay将纤毛虫分为 3 个粒级(10—15 μm、30 μm、40—60 μm),进行了一周年的生长率调查,3个粒级的 Q10为 2.2—3.0,平均为 2.6。Hansen 等[44]总结了体长为2—2000 μm的浮游动物的摄食率和生长率的 Q10的平均值为 2.8,此后,Levinsen 等[60]和Hansen 等[43]都用 Q10=2.8。

图3 自然海区现场的浮游纤毛虫生长率的测定地点(·)分布图Fig.3 Locations of in situ incubation stations for planktonic ciliate growth rates

Nielsen 和 Kiorboe[47]用 Q10=2.6 测量了不同粒级纤毛虫生长率的季节变化,发现3个粒级异养纤毛虫(10—15 μm、30 μm、40—60 μm)和自养纤毛虫Laboea strobila(55 μm)的生长率有共同的季节变化:春季生长率开始增加,7月和8月生长率最高,秋季降低。

Nielsen 和 Kiorboe[47]利用现场实验的数据,得出纤毛虫生长率和温度(T)、纤毛虫体积(V)的关系为:

Levinsen等[60]在格陵兰一个海湾在1.4℃下进行培养得出的纤毛虫生长率高于用 Müller和Geller[23]的公式计算出的数值,Levinsen 等[60]认为Müller和 Geller[23]的公式是根据较高温度(17 ±6)℃下得出的数值回归的,不太适用于低温条件下的情况,极地生物可能具有适应极端环境的能力,需要更多的研究完善这个公式。

4.2 现场纤毛虫生长受上行控制的作用

在某一时刻,比较现场培养得出的纤毛虫生长率和用细胞大小及温度模型得出的纤毛虫内禀生长率,可以用来估计这个时刻纤毛虫在现场的饵料供应情况。Gilron和Lynn[51]在寡营养的热带发现实际测得的生长率比模型得出的生长率低一个量级,所以这个海区纤毛虫饵料不足。Leakey等[64]发现在Sutton Harbor这两个数值相差不大,因此纤毛虫的饵料供应是充足的。Nielsen和Kiorboe[47]发现除了小型的纤毛虫外,优势纤毛虫类群的生长率与饵料浓度关系不大且都接近内禀生长率,因此,这些优势类群的饵料是充足的,而小型纤毛虫的饵料是细菌,它们的饵料浓度不足,因此生长率不高。而那些不占优势的类群因饵料不足,生长率较低。

纤毛虫的生长率受温度和饵料的共同影响,对于纤毛虫周年的生长率变化,Nielsen和Kiorboe[47]认为温度变化对生长率变化的贡献为75%—97%,纤毛虫很少受到饵料不足的影响。

4.3 水华期纤毛虫的生长情况

实验室中得出的纤毛虫的生长率接近甚至超过许多浮游植物在最佳培养条件下的生长率(0.5—2 d-1)[63],也超过一些异养甲藻的生长率[22],所以纤毛虫被认为对浮游植物丰度的变化反应迅速,和异养甲藻一起,可以有效抑制初起水华[22],这也被认为是高营养盐低叶绿素(HNLC,High Nutrient Low Chlorophyll a)海区浮游植物叶绿素浓度低的原因(例 如 Miller 等[71],Sherr 和 Sherr[63],Sherr 和Sherr[72])。

但是自然条件下观察到纤毛虫在水华前期的生长是很少的,在一些赤潮研究中,在赤潮的中后期发现纤毛虫的丰度很高,例如Admiraal和Venekamp[73]发现在北海的Phaeocystis pouchetii发生赤潮时有两种砂壳纤毛虫的丰度很高。但是也有一些调查发现在一些水华期间,微型浮游动物(包括纤毛虫)丰度很低,如 Bjornsen 和 Nielsen[74]及 Nielsen 等[75]。在自然界会遇到单种或几种纤毛虫丰度很高的情况,由于当时的饵料并不是很高,所以物理的汇聚作用也是纤毛虫浓度高的原因之一,但也不排除此前可能发生过饵料浓度高的情况,只是没有被监测到。因为纤毛虫迅速生长的空间小,时间短,所以现场观测到纤毛虫丰度升高和降低的资料几乎没有。在这些纤毛虫丰度升高的事件中,每次事件只有一种或几种纤毛虫丰度升高,是优势种,所以特定饵料种类对应特定纤毛虫种类的营养关系很重要[5,76]。

在人为制造的水华事件中可以监测纤毛虫的变化,其中最著名的是在HNLC海区进行铁加富实验制造的水华,但是在这些实验中,纤毛虫的动态不同。例如,在亚北极太平洋,在Landry等[57]用围隔制造的水华中,纤毛虫生长率并没有随之增加,作者怀疑实验水体中的小型桡足类、捕食性的纤毛虫和异养甲藻限制了植食性纤毛虫的丰度。在东赤道太平洋进行的现场铁加富实验表明,在添加铁后,浮游植物生长,>20 μm 的纤毛虫的生物量也增加[77],在亚北极太平洋进行的现场铁加富实验SEEDS计划中,在加富水体中从加富的第2天到第13天纤毛虫丰度减少[78]。在南大洋进行的的现场铁加富实验EisenEx计划中,纤毛虫在加富水体中并没有明显升高的趋势[79]。

4.4 缺氧对纤毛虫生长的影响

缺氧对纤毛虫的生长有不同的影响。在Chesapeake湾,6月下层水体发生缺氧,在缺氧区有与上层不同的纤毛虫群落,生长率是上层纤毛虫的两倍,达1.18—2.36 d-1。在8月的缺氧区,上层和下层缺氧区的纤毛虫群落是相同的,但是缺氧区的纤毛虫几乎不生长[56]。

5 纤毛虫的生产力

根据纤毛虫生长率和生物量就可以估计纤毛虫的生产力,Lynn 和 Montagnes[80]根据当时已经报导的纤毛虫生物量数据,估计全球不同海区纤毛虫的生产力,由于当时缺乏生长率的资料,他们的估计使用了一个数值:0.69 d-1(即加倍时间为1d),所以是很简单的估计。

大多数对纤毛虫生产力的估计是根据纤毛虫生长率和生物量,与桡足类的生产力相比,纤毛虫的生产力较大。在Solent Estuary,砂壳纤毛虫的年生产力为0.6 mg C/L[49];在 Kattegat Bay,纤毛虫群落(包括红色中缢虫)的年生产力为57 g C/m2或2 g C/m3,桡足类群体的生产力为 12 g C m-2a-1[47];在Narragansett Bay,从3月到10月,砂壳纤毛虫群体的生产力日平均为14 mg C/m3,年生产力为3.3 g C/m3,桡 足 类 的 生 产 力 为 13 mg C m-3d-1[81];在Southampton Water,浮游纤毛虫的日生产力为<1—141 mg C/m3,年生产力为 2.2—9.2 g C/m3,而桡足类生产力为 0.6—1.6 g C m-3a-1[50];在 Gulf of Maine 纤毛虫的生产力为 0.16 g C m-3a-1[45];在Georgia estuary,夏季无壳纤毛虫群体(<20 μm)的生产力在潮溪内为 1.2 mg C m-3h-1,在河口为 0.03 mg C m-3h-1,冬季则分别为0.05 mg C m-3h-1和0.07 mg C m-3h-1[82]

Zervoudaki等[83]利用纤毛虫最大清滤率、摄食率和毛生长率0.33 d-1来估计纤毛虫的生产力,在土耳其海峡纤毛虫生产力为0.2—41 mg C m-2d-1。

6 小结

综上所述,国外在实验室内和海上现场对浮游纤毛虫的生长率已进行了比较广泛的研究。在实验室内12种砂壳纤毛虫的内禀生长率变化范围为0.45—2.7 d-1;22种无壳纤毛虫的內禀生长率(除Strombidium sulcatum的内禀生长率可达8.3 d-1外)变化范围为0.1—3.05 d-1。纤毛虫内禀生长率与饵料种类、温度等有密切关系。虽然纤毛虫内禀生长率高于浮游植物内禀生长率,但是在自然海区纤毛虫随水华发生而迅速增长的情况并不常见。现场培养(海水分粒级培养法)是估计自然海区纤毛虫生长率的常用方法,目前研究的海区主要局限在温带近岸海区,热带和寒带大洋海区的资料较少。对纤毛虫次级生产的研究表明纤毛虫次级生产大于桡足类次级生产。

[1] Azam F,Fenchel T,Field J G,Gray J S,Meyerreil L A,Thingstad F.The ecological role of water-column microbes in the sea.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1983,10(3):257-263.

[2] Heinbokel J F.Studies on the functional role of tintinnids in the Southern California Bight. I. Grazing and growth rates in laboratory cultures.Marine Biology,1978,47(2):177-189.

[3] Capriulo G M. Feedingoffield collected tintinnid microzooplankton on natural food.Marine Biology,1982,71(1):73-86.

[4] Lei Y L,Xu K D,Song W B.Ecological and morphological studies on Strombidium sulcatum,a harmful ciliate during algae cultivation.Journal of Fishery Sciences of China,1996,3(4):39-47.

[5] Montagnes D J S,Lessard E J.Population dynamics of the marine planktonic ciliate Strombidinopsis multiauris:its potential to control phytoplankton blooms.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,1999,20(2):167-181.

[6] Fenchel T,Jonsson P R.The functional biology of Strombidium sulcatum,a marine oligotrich ciliate(Ciliophora,Oligotrichina).Marine Ecology Progress Series,1988,48(1):1-15.

[7] Ohman M D,Snyder R A.Growth kinetics of the omnivorous oligotrich ciliate Strombidium sp.Limnology and Oceanography,1991,36(5):922-935.

[8] Stoecker D K,Silver M W,Michaels A E,Davis L H.Obligate mixotrophy in Laboea strobila,a ciliate which retains chloroplasts.Marine Biology,1988,99(3):415-423.

[9] Putt M,Stoecker D K.An experimentally determined carbon:Volume ratio for marine oligotrichous ciliates from estuarine and coastal waters.Limnology and Oceanography,1989,34(6):1097-1103.

[10] Gismervik I.Numerical and functional responses of choreo- and oligotrich planktonic ciliates.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,2005,40(2):163-173.

[11] Montagnes D J S.Growth responses of planktonic ciliates in the genera Strobilidium and strombidium.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1996,130(1):241-254.

[12] Jonsson P R.Particle size selection,feeding rates and growth dynamics of marine planktonic oligotrichous ciliates(Ciliophora,Oligotrichina).Marine Ecology Progress Series,1986,33(3):265-277.

[13] Verity P G.Measurement and simulation of prey uptake by marine planktonic ciliates fed plastidic and aplastidic nanoplankton.Limnology and Oceanography,1991,36(4):729-750.

[14] Stoecker D,Guillard R R L,Kavee R M.Selective predation by Favella ehrenbergii(Tintinnia)on and among dinoflagellates.Biological Bulletin,1981,160(1):136-145.

[15] Verity P G,Stoecker D.Effects of Olisthodiscus luteus on the growth and abundance of tintinnids.Marine Biology,1982,72(1):79-87.

[16] Clough J, Strom S. Effects of Heterosigma akashiwo(Raphidophyceae)on protist grazers:laboratory experiments with ciliatesand heterotrophic dinoflagellates. Aquatic Microbial Ecology,2005,39(2):121-134.

[17] Rose J M,Fitzpatrick E,Wang A,Gast R J,Caron D A.Low temperature constrains growth rates but not short-term ingestion rates of Antarctic ciliates.Polar Biology,2013,36(5):645-659.

[18] Pedersen M F,Hansen P J.Effects of high pH on the growth and survival of six marine heterotrophic protists.Marine Ecology Progress Series,2003,260:33-41.

[19] Montagnes D J S,Berger J D,Taylor F J R.Growth rate of the marine planktonic ciliate Strombidinopsis cheshiri Snyder and Ohman as a function of food concentration and interclonal variability.Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,1996,206(1):121-132.

[20] Buskey E J,Hyatt C J.Effects of the Texas(USA)‘brown tide’alga on planktonic grazers.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1995,126(1):285-292.

[21] Jeong H J,Shim J H,Lee C W,Kim J S,Koh S M.Growth and grazing rates of the marine planktonic ciliate Strombidinopsis sp.on red-tide and toxic dinoflagellates. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology,1999,46(1):69-76.

[22] Strom S L,Morello T A.Comparative growth rates and yields of ciliates and heterotrophic dinoflagellates.Journal of Plankton Research,1998,20(3):571-584.

[23] Müller H,Geller W.Maximum growth rates of aquatic ciliated protozoa the dependence on body size and temperature reconsidered.ArchivFurHydrobiologie, 1993, 126(3):315-327.

[24] Chen B Z,Liu H B,Lau M T S.Grazing and growth responses of a marine oligotrichous ciliate fed with two nanoplankton:does food quality matter for micrograzers?.Aquatic Ecology,2010,44(1):113-119.

[25] Stoecker D K,Silver M W.Replacement and aging of chloroplasts in Strombidium capitatum(Ciliophora,Oligotrichida).Marine Biology,1990,107(3):491-502.

[26] Tumantseva N,Kopylov A.Reproduction and production rates of planktic infusoria in coastal waters of Peru.Oceanology of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR,1985,25(3):390-394.

[27] Rivier A,Brownlee D,Sheldon R,Rassoulzadegan F.Growth of microzooplankton: A comparative study of bactivorous zooflagellates and ciliates.Marine Microbial Food Webs,1985,1(1):51-60.

[28] Allali K,Dolan J,Rassoulzadegan F.Culture characteristics and orthophosphate excretion of a marine oligotrich ciliate,Strombidium sulcatum,fed heat-killed bacteria.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1994,105(1/2):159-165.

[29] Martinez E A.Effects of temperature and food concentration on competitive interaction in three species of marine Ciliophora.Caribbean Journal of Science,1983,19:1-7.

[30] Montagnes D J S,Kimmance S A,Atkinson D.Using Q10:Can growth rates increase linearly with temperature?Aquatic Microbial Ecology,2003,32(3):307-313.

[31] Kamiyama T.Growth and grazing responses of tintinnid ciliates feeding on the toxic dinoflagellate Heterocapsa circularisquama.Marine Biology,1997,128(3):509-515.

[32] Hansen P J.Growth and grazing response of a ciliate feeding on the red tide dinoflagellate Gyrodinium aureolum in monoculture and in mixture with a non-toxic alga.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1995,121(1/3):65-72.

[33] Hansen P J.The red tide dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense:effects on behavior and growth of a tintinnid ciliate.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1989,53(2):105-116.

[34] Rosetta C H,McManus G B.Feeding by ciliates on two harmful algal bloom species,Prymnesium parvum and Prorocentrum minimum.Harmful Algae,2003,2(2):109-126.

[35] Stoecker D,Davis L H,Provan A.Growth of Favella sp.(Ciliata,Tintinnina)and other microzooplankters in cages incubated in situ and comparison to growth in vitro.Marine Biology,1983,75(2/3):293-302.

[36] Aelion C M,Chisholm S W.Effect of temperature on growth and ingestion rates of Favella sp.Journal of Plankton Research,1985,7(6):821-830.

[37] Verity P G,Villareal T A.The relative food value of diatoms,dinoflagellates, flagellates, and cyanobacteria for tintinnid ciliates.Archiv Für Protistenkunde,1986,131(1):71-84.

[38] Verity P G.Grazing,respiration,excretion,and growth rates of tintinnids.LimnologyandOceanography, 1985, 30(6):1268-1282.

[39] Gold K.Growth characteristics of the mass-reared tintinnid Tintinnopsis beroidea.Marine Biology,1971,8(2):105-108.

[40] Gold K.Methods for growing tintinnida in continuous culture.American Zoologist,1973,13(1):203-208.

[41] MartinezE A. Sensitivity ofmarine ciliates (Protozoa,Ciliophora)to high thermal stress.Estuarine and Coastal Marine Science,1980,10(4):369-381.

[42] Gismervik I,Andersen T,Vadstein O.Pelagic food webs and eutrophication of coastal waters:Impact of grazers on algal communities.Marine Pollution Bulletin,1996,33(1):22-35.

[43] Hansen B W,Jensen F.Specific growth rates of protozooplankton in the marginal ice zone of the central Barents Sea during spring.Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom,2000,80(1):37-44.

[44] Hansen P J,Bjørnsen P K,Hansen B W.Zooplankton grazing and growth:Scaling within the 2—2,000μm body size range.Limnology and Oceanography,1997,42(4):687-704.

[45] Montagnes D J S,Lynn D H,Roff J C,Taylor W D.The annual cycle of heterotrophic planktonic ciliates in the waters surrounding the isles of shoals,Gulf of Maine:An assessment of their trophic role.Marine Biology,1988,99(1):21-30.

[46] Pérez M T,Dolan J R,Fukai E.Planktonic oligotrich ciliates in the NW Mediterranean:growth ratesand consumption by copepods.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1997,155:89-101.

[47] Nielsen T G,Kiorboe T.Regulation of zooplankton biomass and production in a temperate,coastalecosystem.2. ciliates.Limnology and Oceanography,1994,39(3):508-519.

[48] Dolan J R,Perez M T.Costs,benefits and characteristics of mixotrophy in marine oligotrichs.Freshwater Biology,2000,45(2):227-238.

[49] Burkill P H.Ciliates and other microplankton components of a nearshore food-web:Standing stocks and production processes.Annales De L Institut Oceanographique,1982,58:335-349.

[50] Leakey R J G,Burkill P H,Sleigh M A.Planktonic ciliates in Southampton Water:Abundance,biomass,production,and role in pelagic carbon flow.Marine Biology,1992,114(1):67-83.

[51] Gilron G L,Lynn D H.Estimates of in situ population growth rates of four tintinnine ciliate species near Kingston Harbour,Jamaica.Estuarine,Coastal and Shelf Science,1989,29(1):1-10.

[52] Heinbokel J.Diel periodicities and rates of reproduction in natural populations of tintinnines in the oligotrophic waters off Hawaii,September 1982.Marine Microbial Food Webs,1987,2(1):1-14.

[53] Sherr E B,Rassoulzadegan F,Sherr B F.Bacterivory by pelagic choreotrichous ciliates in coastal waters of the NW Mediterranean Sea.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1989,55(2):235-240.

[54] Verity P G.Growth-rates of natural tintinnid populations in Narragansett Bay.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1986,29(2):117-126.

[55] Roman M R,Rublee P A.Containment effects in copepod grazing experiments:a plea to end the black box approach.Limnology and Oceanography,1980,25(6):982-990.

[56] Dolan J R.Microphagous ciliates in mesohaline chesapeake bay waters:Estimates of growth rates and consumption by copepods.Marine Biology,1991,111(2):303-309.

[57] Landry M R,Gifford D J,Kirchman D L,Wheeler P A,Monger B C.Direct and indirect effects of grazing by Neocalanus plumchrus on plankton community dynamics in the subarctic Pacific.Progress in Oceanography,1993,32(1):239-258.

[58] Heinbokel J F.Reproductive rates and periodicities of oceanic tintinnine ciliates.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1988,47(3):239-248.

[59] Verity P G,Stoecker D K,Sieracki M E,Nelson J R.Grazing,Growth and mortality of microzooplankton during the 1989 North Atlantic Spring Bloom at 47°N,18°W.Deep-Sea Research I,1993,40(9):1793-1814.

[60] Levinsen H,Nielsen T G,Hansen B W.Plankton community structure and carbon cycling on the western coast of Greenland during the stratified summer situation. II. Heterotrophic dinoflagellates and ciliates.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,1999,16(3):217-232.

[61] Fileman E,Petropavlovsky A,Harris R.Grazing by the copepods Calanus helgolandicus and Acartia clausi on the protozooplankton community at station L4 in the Western English Channel.Journal of Plankton Research,2010,32(5):709-724.

[62] Gifford D J.Laboratory culture of marine planktonic Oligotrichs(Ciliophora,Oligotrichida).Marine Ecology Progress Series,1985,23(3):257-267.

[63] Sherr E B,Sherr B F.Bacterivory and herbivory:key roles of phagotrophic protists in pelagic food webs.Microbial Ecology,1994,28(2):223-235.

[64] Leakey R J G,Burkill P H,Sleigh M A.Ciliate growth rates from Plymouth Sound:Comparison of direct and indirect estimates.Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom,1994,74(4):849-861.

[65] Tiselius P.Contribution of aloricate ciliates to the diet of Acartia clausi and Centropages hamatus in coastal waters.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1989,56(1):49-56.

[66] Fessenden L,Cowles T J.Copepod predation on phagotrophic ciliates in oregon coastal waters.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1994,107(1/2):103-111.

[67] Hansen B,Christiansen S,Pedersen G.Plankton dynamics in the marginal ice zone of the central Barents Sea during spring:Carbon flow and structure of the grazer food chain.Polar Biology,1996,16(2):115-128.

[68] Lonsdale D J,Cosper E M,Kim W S,Doall M,Divadeenam A,Jonasdottir S H.Food web interactions in the plankton of Long Island bays,with preliminary observations on brown tide effects.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1996,134(1/3):247-263.

[69] Lonsdale D J,Caron D A,Dennett M R,Schaffner R.Predation by Oithona spp.on protozooplankton in the Ross Sea,Antarctica.Deep-Sea Research II,2000,47(15/16):3273-3283.

[70] Fileman E, Burkill P. The herbivorous impact of microzooplankton during two short-term Lagrangian experiments off the NW coastofGalicia in summer1998. Progressin Oceanography,2001,51(2):361-383.

[71] Miller C,Frost B,Booth B,Wheeler P,Landry M,Welschmeyer N.Ecological processes in the subarctic Pacific:iron limitation cannot be the whole story.Oceanography,1991,4(2):71-78.

[72] Sherr E B,Sherr B F.Capacity of herbivorous protists to control initiation and development of mass phytoplankton blooms.Aquatic Microbial Ecology,2009,57(3):253-262.

[73] Admiraal W,Venekamp L A H.Significance of tintinnid grazing during blooms of Phaeocystis pouchetii(Haptophyceae)in Dutch coastal waters.Netherlands Journal of Sea Research,1986,20(1):61-66.

[74] Bjørnsen P K,Nielsen T G.Decimeter scale heterogeneity in the plankton during a pycnocline bloom of Gyrodinium aureolum.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1991,73(2):263-267.

[75] Nielsen T G, Kiorboe T, Bjornsen P K. Effectsofa Chrysochromulina-Polylepis subsurface bloom on the planktonic community.Marine Ecology Progress Series,1990,62(1):21-35.

[76] Tillmann U.Interactions between planktonic microalgae and protozoan grazers.Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology,2004,51(2):156-168.

[77] Landry M R,Constantinou J,Latasa M,Brown S L,Bidigare R R,Ondrusek M E.Biological response to iron fertilization in the eastern equatorialPacific (IronExII). III. Dynamicsof phytoplankton growth and microzooplankton grazing. Marine Ecology Progress Series,2000,201:57-72.

[78] Saito H,Suzuki K,Hinuma A,Ota T,Fukami K,Kiyosawa H,Saino T,Tsuda A.Responses of microzooplankton to in situ iron fertilization in the western subarctic Pacific(SEEDS).Progress in Oceanography,2005,64(2):223-236.

[79] Henjes J,Assmy P,Klaas C,Verity P,Smetacek V.Response of microzooplankton(protists and small copepods)to an ironinduced phytoplankton bloom in the Southern Ocean(EisenEx).Deep-Sea Research Part I,2007,54(3):363-384.

[80] Lynn D H,Montagnes D J S,Dale T,Gilron G L,Strom S L.A Reassessment of the Genus Strombidinopsis (Ciliophora,Choreotrichida)with descriptions of 4 new planktonic species and remarks on its taxonomy and phylogeny.Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom,1991,71(3):597-612.

[81] Verity P G. Abundance, community composition, size distribution,and production rates of tintinnids in Narragansett Bay,Rhode-Island.Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science,1987,24(5):671-690.

[82] Sherr E B,Sherr B F,Fallon R D,Newell S Y.Small,aloricate ciliates asa majorcomponentofthe marine heterotrophic nanoplankton.Limnology and Oceanography,1986,31(1):177-183.

[83] Zervoudaki S,Christou E D,Assimakopoulou G,Örek H,Gucu A C, GiannakourouA, PittaP, Terbiyik T, YucelN,Moutsopoulos T,Pagou K,Psarra S,Özsoy E,Papathanassiou E.Copepod communities,production and grazing in the Turkish Straits System and the adjacent northern Aegean Sea during spring.Journal of Marine Systems,2011,86(3):45-56.

参考文献:

[4] 类彦立,徐奎栋,宋微波.单胞藻培养中一敌害纤毛虫——具沟急游虫的生态习性及形态学初探.中国水产科学,1996,3(4):39-47.