Exploring Chinese Consumers’ Shopping Value across Retail Outlets

2014-04-29LizhuDavis

Lizhu Davis

This study aims to explore Chinese consumers shopping value. Using shopping value dimensions identified through a qualitative study, a quantitative study was conducted to assess consumers shopping value perceptions as to their shopping experiences in two retail outlets: department stores and mass merchandisers. The findings suggest that while Chinese consumers tend to shop at both retail outlets for self-gratification value and social interaction value, they gain a broader range of hedonic shopping value at department stores and experience more functional shopping value at supermarkets. The findings highlight the importance of shopping experiences and value for Chinese consumers.

Keywords: shopping value, department stores, supermarkets

1 INTRODUCTION

China has experienced rapid economic growth since the 1980s. With an annual average economic growth rate of about 10% since the year 1990, the annual per capital disposable income of urban residents increased about 250% from 2000 to 2008 (China Statistical Yearbook, 2009). Dramatically increased consumer spending power and a growing wealthy middle class have attracted many international retailers to Chinese markets, especially since China joined the WTO in 2001 (Liu, 2007). Meanwhile, new retail formats such as supermarkets, warehouse clubs, specialty stores, and convenience stores have become common (Wang, Li, & Liu, 2008). Retail sales of consumer goods increased 325% from 1998 to 2008 and reached 10.8 trillion RMB in 2008 (China Statistical Yearbook, 2009). The rapid growth has transformed the Chinese retail market which has become a very competitive battlefield for both international and domestic retailers (Wang et al., 2008). To succeed in this important and competitive market, it is critical to understand not only Chinese consumers needs and wants but also their shopping and store patronage behavior. However, little has been done to systematically investigate consumers patronage behavior in different retail channels and stores (Uncles & Kwok, 2009). Failure to fully understand Chinese consumers unique shopping and consumption behaviour hinder the success of some international retailers. Some recent examples include Best Buy and Home Depot from the United State.

Value is one of the most important measures for gaining a competitive edge (Parasuraman, 1997) and the basis for all marketing activities (Holbrook, 1994). It is the key outcome of consumption experiences (Holbrook, 1986) and the most important indicator of repurchase intentions (Parasurman & Grewal, 2000). In the retail market, shopping value affects retail outcomes and enhances such retail variables as consumer satisfaction (Babin, Lee, Kim, & Greffin, 2005), customer share (Babin & Attaway, 2000), patronage intentions, customer loyalty, and word-of-mouth (Jones, Reynolds, & Arnold, 2006). Retailers, therefore, must deliver value to their consumers to enhance customer satisfaction and loyalty. With increasing purchasing power and abundant choices of retail outlets and products, Chinese consumers have become demanding (Wang et al., 2008). Gaining shopping experience and value has become important for them (Davis, 2009). Understanding Chinese consumers shopping value and its effect on store patronage behavior such as store choices and preferences has become critical for international retailers and marketers (Wang, Chen, Chan, & Zheng, 2000; Zhang et al., 2008). Since the main body of shopping value literature was established based on Western consumers and markets, the first step would be to determine if established shopping value constructs and theories are also applicable to Chinese consumers. The second important step should be to investigate Chinese consumers value perceptions in different retail outlets to better understand their shopping behavior. The purpose of this study is, therefore, 1) to identify key consumer shopping value dimensions that Chinese consumers pursue in the marketplace; 2) to identify any similarities and differences in Chinese consumers value perceptions when shopping at two major outlets, department stores and supermarkets.

Department stores are non-self-service retail outlets selling a large variety of merchandise that is organized into departments (Uncles & Kwok, 2009). Department stores were introduced in China in the era of the central-planned economy. Before the economic reform beginning in the late 1970s, they served as the sole distribution channel for manufactured consumer goods (Chan, Perez, Perkins, & Shu, 1997). Department stores still serve as key retail outlets that provide Chinese consumers quality merchandise as well as one-stop shopping experiences. Supermarkets, on the other hand, were first introduced in the 1980s. They started in major Chinese cities including Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou (Mai & Zhao, 2004). Supermarkets expanded rapidly during the past two decades. During 2002-2007, the supermarket sector expanded with a cumulative growth rate of 22% in value sales, 19% in selling space, and 13% in outlets (Euromonitor, 2008). They are estimated to account for about 25% of the total Chinese retail market (Zhang, 2004). Similar to mass merchandisers in the United States, supermarkets in China carry a large assortment of merchandise including fresh foods, groceries, home goods, as well as textiles and apparel. Many supermarkets have multiple floors, each focusing on a different product category, just like department stores. Chinese consumers demand for high quality and large varieties of merchandise, from groceries, home goods, to apparel and accessories, makes supermarkets very popular. Today, department stores and supermarkets are major retail outlets that Chinese consumers rely on to satisfy their needs and wants (Wong & Dean, 2009). With an increasingly crowded retail environment, these two popular retail outlets in China are facing fierce competition. By understanding consumers value perceptions in each retail outlet, supermarkets and department stores can understand their consumers better, which can lead to better customer satisfaction and value delivery. So, the findings of this study not only contribute to Chinese consumer shopping literature by understanding Chinese consumers shopping behavior, but also provide insight that can enable department stores and supermarkets to better position themselves in the local retail market.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Consumption Value

Holbrook (1986) defined value as “an interactive relativistic preference experience” (p.32) and argued that value is found in the experience of consumption of products (services) rather than in the purchase, although purchase can be a part of consumption experience. Therefore, although a product may have many attributes, those attributes come to represent consumer value only after they are appreciated or perceived by consumers. Holbrook (1986) also developed a value typology that was structured on broad conceptual classifications. According to Holbrooks value typology (1986), consumer value in the consumption experience has three dimensions: 1) extrinsic vs. intrinsic, 2) self- vs. other-oriented and 3) active vs. passive. Extrinsic value and intrinsic value are also known as utilitarian value and hedonic value, respectively. Value is self-oriented when a consumer appreciates a product or experience for his/her own sake and other-oriented when a consumer looks beyond self to others such as family, friends and the universe. Furthermore, value is active when it involves things done by an individual and reactive when it comes from things done to an individual (Holbrook, 1986). When combining those three dimensions, eight different types of consumption value emerge: four self-oriented values and four other-orientated values. Self-oriented values include efficiency (extrinsic/active), excellence (extrinsic/passive), play (intrinsic/active), and aesthetics (intrinsic/passive); and other-oriented values include politics (extrinsic/active), esteem (extrinsic/passive), morality (intrinsic/active), and religion (intrinsic/passive).

Zaithaml (1988) emphasized product value and conceptualized consumer perceived value (CPV) as “the consumers overall assessment of the utility of a product based on a perception of what is received and what is given” (p.14). That is, CPV is a trade-off between benefits and sacrifices perceived by the consumer when considering a suppliers offering. The benefit component of value include salient intrinsic attributes, extrinsic attributes, perceived quality, and other aspects such as convenience and appreciation; the sacrifice components include both monetary prices and non-monetary prices such as time, energy, and effort to obtain products and services (Zaithaml, 1988). Sheth, Newman, and Gross (1991) further extended the concept of CPV and developed a theoretical framework of consumption value. According to this theoretical framework, consumer choice of products and/or services is a function of multiple consumption value dimensions including functional value, social value, emotional value, epistemic value, and conditional value. Functional value is the perceived utility acquired from an alternatives capacity for functional, utilitarian, or physical performance; social value is the perceived utility acquired from an alternatives association with one or more specific social groups; emotional value is the perceived utility acquired from an alternatives capacity to arouse feelings or affective states; epistemic value is the perceived utility acquired from an alternatives capacity to arouse curiosity, provide novelty, and/or satisfy a desire for knowledge; and conditional value is the perceived utility acquired by an alternative as the result of the specific situation or set of circumstances facing the choice maker (Sheth et al., 1991).

It is clear that consumption value has been defined from different views. Some scholars view it as the outcome of consumption experiences (Holbrook, 1986) and others view it as the criteria for product/service choices (Sheth et al., 1991). Meanwhile, some researchers view it from the economic perspective and regard it as the trade-off between benefits and sacrifices (e.g. Zaithaml, 1988). Based on the different definitions, a number of different value dimensions have been identified.

2.2 Consumer Shopping Value

Based upon consumption value research, scholars approached the concept and dimensions of shopping value in a number of ways. Following Holbrook (1986), Babin, Darden, and Griffin (1994) defined shopping value as the evaluation of the overall worth of a shopping experience. As the outcome of a shopping trip, Babin et al. (1994) proposed two fundamental dimensions to shopping value, utilitarian and hedonic value, which is the extrinsic versus intrinsic dimension of Holbrooks value typology. Utilitarian value relates to shopping as a work mentality, which can explain shopping trips as “an errand” or “work” and emphasizes task accomplishment (Babin et al., 1994). In contrast, hedonic value involves fun, playfulness, and sensory reactions, which reflects shoppings potential entertainment and emotional worth and focuses on the immediate gratification provided by the shopping experience (Babin et al., 1994). Rintamiki, Kanto, Kuusela, and Spence (2006) argued the importance of recognizing social value as an independent shopping value construct rather than a sub-dimension of hedonic value. They (2006) further proposed that utilitarian value derives from money saving and shopping convenience; hedonic value derives from exploration and entertainment; and social value is gained from status and self-esteem enhancement.

Mathwick, Malhotra, and Rigdon (2001), on the other hand, followed the value typology of Holbrook (1986) to investigate and assess retail shopping experiences in Internet and catalogue shopping contexts. Focusing only on self-oriented value, Mathwick et al. (2001) argue that experiential shopping value has four dimensions: consumer return on investment (CROI), service excellence, playfulness, and aesthetic appeal. Using a hierarchical structure, Mathwick et al. (2001) conceptualized escapism and enjoyment as indicators of the higher order dimension of playfulness; visual appeal and entertainment as indicators of aesthetics; and efficiency and economic value as indicators of consumer return on investment. Also based on Holbrooks (1986) theoretical framework of value typology, Kim (2002) discussed and contrasted consumer value experienced by mall and Internet shopping in a conceptual article. In the discussion, playfulness is acquired through sensory stimulation, entertainment and social interaction; aesthetics through ambience; efficiency through convenience and resources (time, effort and money); and excellence through product performance and customer service. It can be seen that although Holbrooks value typology provides a framework for analyzing shopping value in different retail channels, researchers disagree on the components of each value dimension.

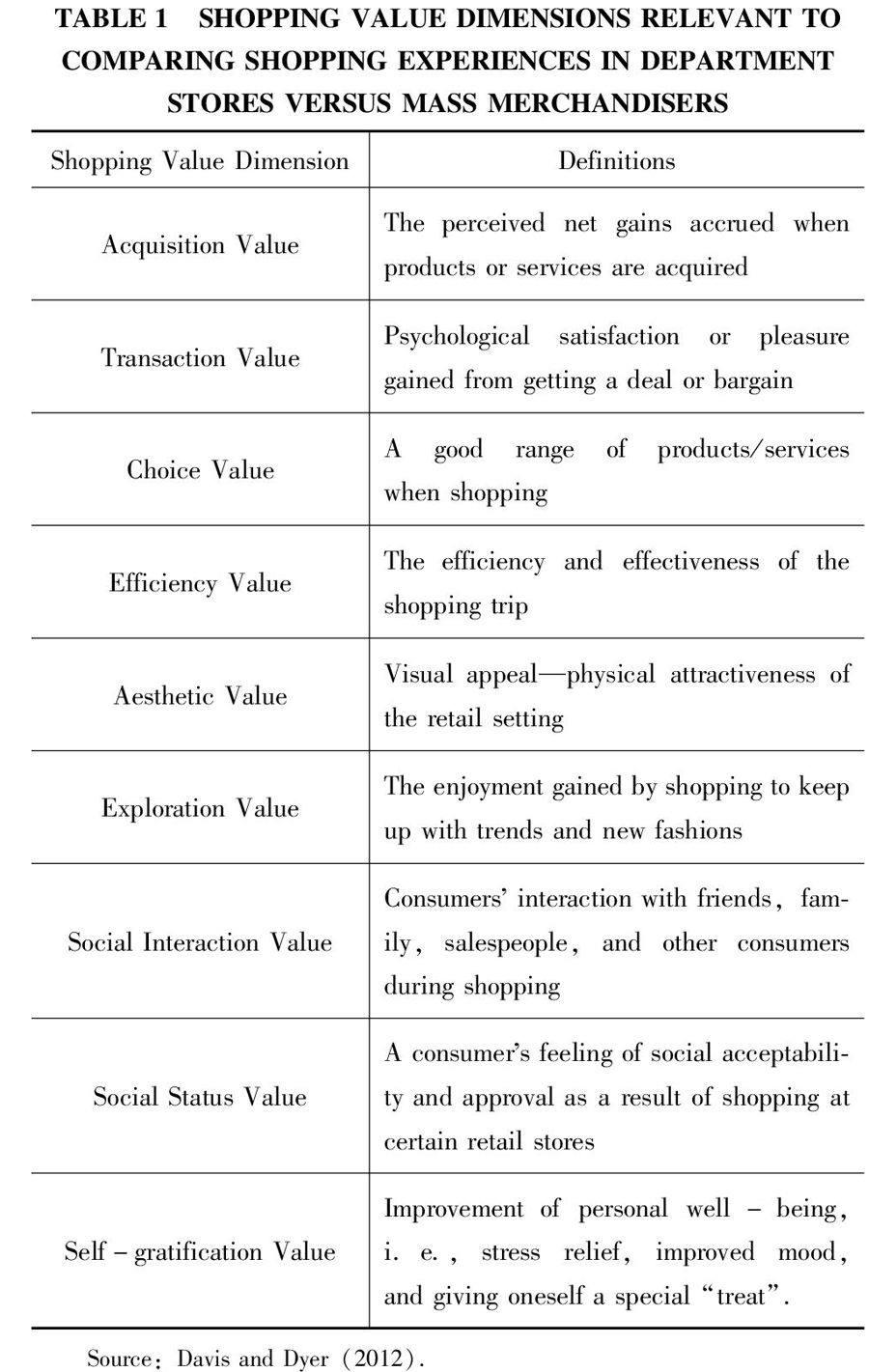

Overall, the literature on consumer shopping value is fragmented. In an effort to provide a holistic view of shopping value, Davis and Dyer (2012) investigated shopping value dimensions based on the value theory developed by John Dewey (1939) that argues that value is derived from the fulfilment of consumers needs and wants. Consumers shop to satisfy a broad range of personal and social needs that go beyond pure acquisition of goods and services (Tauber, 1972; Westbrook & Black, 1985). Viewed broadly, consumers go shopping because they experience a need and recognize that shopping activities can satisfy that need. Based on Deweys value theory, when the need is fulfilled, whether actual or perceived, the consumer then develops a value perception of the experience that is associated with the needs and wants that motivated the foray into the marketplace. That is, satisfying a specific shopping need leads to the consumers perception of gaining a specific shopping value (Davis & Dyer, 2012). By connecting consumer shopping motivations and value perception, Davis and Dyer (2012) identified nine shopping value dimensions that are most relevant to compare consumers shopping experiences in department stores and mass merchandisers. Those nine dimensions are acquisition value, transaction value, efficiency value, choice value, aesthetic value, exploration value, self-gratification value, social interaction value, and social status value. The definition of each value dimension is listed in Table 1.

2.3 Consumption Value and Chinese Consumers

Although some researchers have used the value concept to study Chinese consumers, much of the effort has been focused on personal value and cultural value. For example, Tai (2008) investigated the relationship between personal values and shopping orientation among adult working consumers in Taipei, Hong Kong and Shanghai. The study found that Chinese consumers in greater China share similar personal values, and there existed significant relationships between personal values and shopping orientation. Specifically, self-actualization value was the most important personal value that affects Chinese consumers shopping orientation (Tai, 2008). Cai and Shannon (2012) found that beside self-actualization (or self-enhancement) value, self-transcendence value, which is related to protecting and enhancing the wellbeing of other people and nature in general, positively affects Chinese consumers attitude towards mall attributes. Chan (2001) also found that the traditional cultural value of collectivism and man-nature orientation positively affect Chinese consumers attitude towards green purchases.

Few studies have explored the role of consumption value in Chinese consumers consumption behavior, and even fewer have tapped into consumer shopping value. First, Chinese consumers were found to emphasize more on the utilitarian or functional value of products (Tse, Belk, & Zhou, 1989). However, with improving personal income and living standards, Chinese consumers may focus more on other dimensions of product and consumption value. Xiao and Kim (2009) reported that functional value, emotional value, and social value conceptualized by Sheth et al. (1991) were positively related with Chinese consumers purchasing of foreign brands. Yu and Bastin (2010), furthermore, explored the relationship of hedonic shopping value and impulsive buying behavior. They (2010) identified five dimensions of hedonic shopping value, namely novelty, fun, praise from others, escapism and social interaction for Chinese consumers. Further empirical study shows that novelty, fun, and praise from others have a significant positive relationship with Chinese consumers impulsive buying behavior (Yu & Bastin, 2010). In conclusion, limited studies confirmed that consumption value is effective for understanding Chinese consumer behavior and more extended research in the area is needed.

Two major retail outlets in China, department stores and supermarkets, may satisfy different consumer needs and wants, as they do in western countries, thus offering different types of shopping value to Chinese consumers. Wong and Dean (2009) found that product quality and customer orientation, or retailers commitment to consumer needs and value delivery, positively related to perceived value for Chinese consumers in supermarkets and department stores respectively. Chinese consumers seek quality and choices at supermarkets and recreational shopping experiences at department stores (Wong & Dean, 2009; Davis, 2009). Department stores are popular destinations for weekend family outings (Chan et al., 1997). Therefore, it is hypothesized that the shopping value that Chinese consumers perceive gaining in department stores is different from that they perceive gaining in supermarkets.

Hypothesis: The shopping value that Chinese consumers perceive gaining from shopping at department stores is different from that they perceive gaining from shopping at supermarkets.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Qualitative Preliminary Study

For the purpose of this study, a qualitative study was first conducted in Northwest China to identify shopping value dimensions that are most relevant to Chinese consumers shopping experiences in department stores and supermarkets. A convenience sample of 18 consumers who frequently engaged in shopping activities participated in in-depth interviews. The majority of them were female consumers. Ten of the participants were in their 20s and 30s and six in their 40s and 50s. The interviews were lightly structured, using focused, open-ended and non-directive questions in which discussions followed participants responses and issues (Mariampolski, 2001). In-depth interviews were conducted in locations that were convenient to participants, including their homes and offices. Each interview was from 30 to 60 minutes long. All the interviews were recorded upon permission and later transcribed into text for interpretation.

Content analysis methods were used to identify possible shopping value dimensions that participants perceived they gained and actively sought from their shopping experiences. Common themes were developed based on the shopping value framework developed by Davis and Dyer (2012). The data reveal that for the majority of participants, shopping is an important part of their daily lives. To satisfy their needs for everyday products and services through shopping, some participants tended to shop around to gain the best economic product value or acquisition shopping value. They valued the broad range of product categories and assortments that provide one-stop-shopping convenience and freedom of choices, and enjoyed the efficiency and effectiveness of their shopping trips. Therefore, choice value and efficiency value are important for participants. Some participants shopped a lot for the excitement and thrill of finding deals and bargains. For many participants, the retail market is an important product and market information source. They liked to shop just to find out about new products and fashions, and discover new trends. Furthermore, for the majority of participants, shopping is about releasing stress and improving mood. More importantly, shopping for them is about socializing with family and friends. Therefore, transaction value, exploration value, self-gratification value, and social interaction value are all important for participants. Finally, some participants also emphasized shopping to appreciate beautiful retail visual displays and enjoy a pleasant shopping environment. Therefore, they sought aesthetic shopping value. In conclusion, the findings reveal that all shopping value dimensions except social status value identified by Davis and Dyer (2012) are also commonly pursued by northwest Chinese consumers.

3.2 Quantitative Study

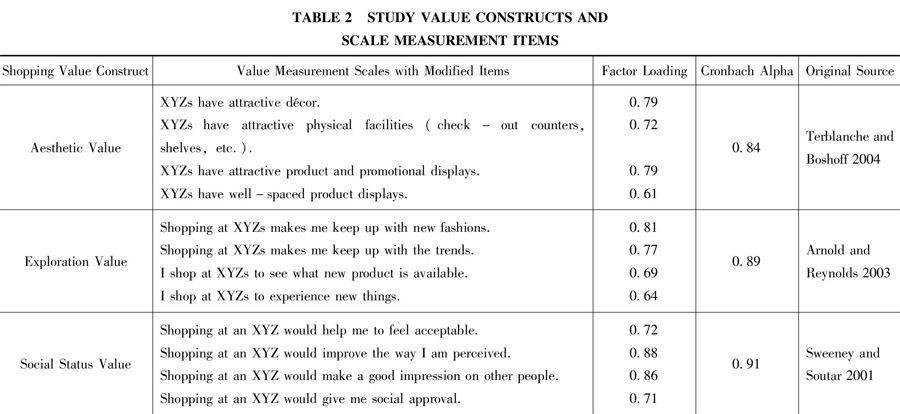

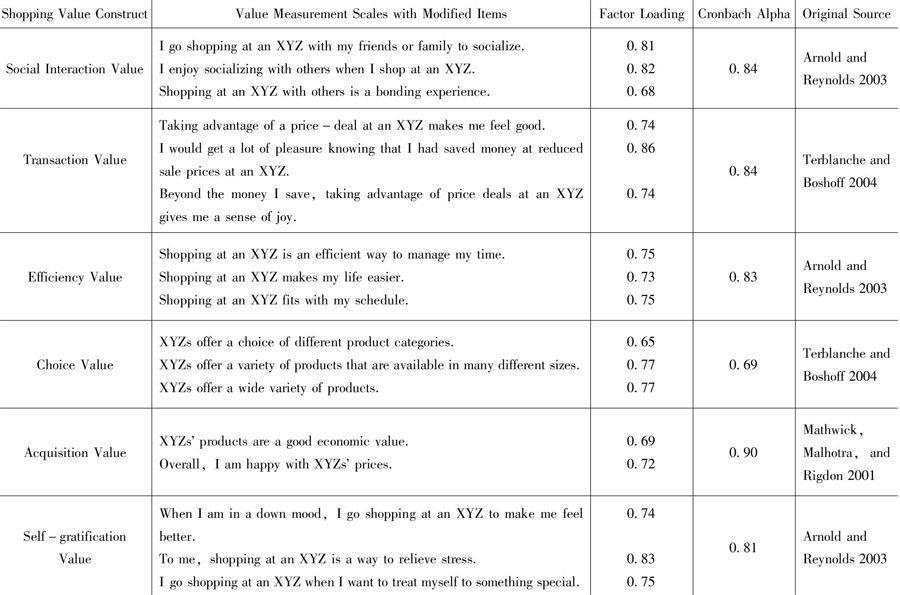

To test the hypothesis, a survey instrument was developed using existing scales adopted from Davis and Dyer (2012) study (See Table 2). The responses to scale items were measured on a seven-point Likert-type scale anchored between “strongly disagree” (1) and “strongly agree” (7). Scales were translated into Chinese and then back-translated into Chinese to ensure accuracy of the Chinese translation (Malhotra, 1996). The data was collected in Lanzhou City, Gansu province. As the capital city of Gansu province, Lanzhou is one of the most important cities in Northwest China. It has the largest economy in Gansu province with a population of 3.32 million. Its retail landscape has changed dramatically since 2000 with the opening of its first supermarket – Lanzhou Hualian. In 2008, the retail sales in the city reached 342.66 billion RMB. However, international retailers have not entered the local market, which makes it appealing to international retailers.

Two hundred fifty-three female Chinese consumers from a convenience sample participated in the study. All respondents shopped at both supermarkets and department stores regularly. The majority of them were 25 to 44 years of age. About 83% of respondents belonged to the Han ethnic group. While 46% of respondents have college education, only 8% of them earn more than 3,000 RMB per month. Therefore, the respondents tend to be younger consumers with relatively lower incomes. The respondents demographic information is presented in Table 3

4 ANALYSIS

To validate the study constructs, a principal component factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted. Factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and loadings of .50 were used as the criteria for retaining items (Hair et al., 2006). Items did not have high loading on any one dimension and those that have high loadings on more than two dimensions were eliminated from further analysis. The factor analysis indicated that after the scale purification, all the remaining items measuring each shopping value construct loaded highly on only one dimension (see Table 2). In conclusion, the factor analysis confirmed that all constructs of the study are valid. Furthermore, each scale satisfied the Cronbachs alpha larger than 0.70 criterion preferred in previous research studies, with the exception of the choice value scale which at 0.69 was considered borderline but acceptable (Peter, 1979; Peterson, 1994) (see Table 2).

To compare participants shopping value perception from their shopping experiences at department stores and supermarkets, a full factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to analyze data. Table 4 presents the MANOVA and ANOVA results. The MANOVA test was used because it is a conservative test that is ideal for controlling for the overall type I error rate for multiple comparisons (Hummel & Sligo, 1971). The p-value of Wilks lambda test was significant at p<0.001, suggesting that overall shopping value that participants perceived at department stores was significantly different from that they perceived at supermarkets (p<0.001). Thus the null hypothesis is supported. The descriptive statistical analysis shows that participants perceived gaining high levels of acquisition value (u = 5.15), transaction (u = 5.01), efficiency (u = 5.01), and choice value (u = 5.57) at supermarkets, and high levels of exploration value (u = 5.46), aesthetic value (u = 5.19), and choice value (u = 5.97) at department stores (see Table 4).

ANOVA tests were used to compare participants perception of each shopping value at department stores versus supermarkets. ANOVA tests show that participants perceived significantly higher levels of acquisition value, that is, what-you-get-from-what-you-give value at supermarkets (u=5.15) than at department stores (u = 3.61). They also perceived significantly higher levels of transaction value, or gaining pleasure by finding deals and bargains, as well as efficiency value at supermarkets (u = 5.01 for both dimensions) than at department stores (u = 4.58 and 4.77, respectively). Meanwhile, participants perceived significantly higher levels of choice value, aesthetic value, exploration value, and social status value at department stores with the mean of 5.97, 5.19, 5.46, and 3.82 respectively. However, there is no significant difference in social interaction value or self-gratification value between department stores (u = 4.34 and 4.63, respectively) and supermarkets (u = 4.41 and 4.33, respectively).

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Although shopping value significantly affect consumers patronage behavior (e.g. Babin & Attaway, 2000), limited studies have explored shopping value and its effects on consumers patronage behavior in China. This research sought to investigate Chinese consumers shopping value perception at department stores and supermarkets, which are two most popular retail outlets in China. The study first explored major shopping value dimensions shared among Chinese consumers using a preliminary qualitative study. The findings from the qualitative study reveal that all value dimensions except social status shopping value from the shopping value framework provided by Davis and Dyer (2012) are common among Chinese consumers. To satisfy their needs for goods and services, Chinese consumers seek acquisition value (economic value of products), choice value (a broad choice of merchandise), and efficiency value (the efficiency of their shopping trips). They also shop to satisfy a broad range of psychological and emotional needs, as Davis, Peyrefitte and Hodges (2012) concluded. The satisfaction of those needs leads to exploration value (finding novelty goods and learning fashion trends), social interaction value (socializing with family and friends), self-gratification value (improving personal well-being), aesthetic value (enjoying pleasant retail visual displays), and transaction value (gaining pleasure from finding a bargain).

The study then explored the similarities and differences in value perception from their shopping experiences at department stores and supermarkets using a follow up quantitative study. The statistical analysis reveals that participants perceived gaining significantly different shopping value at department stores and supermarkets. They perceived significantly higher levels of hedonic shopping value, including exploration value, aesthetic value, and social status value at department stores, which means that they felt learning more about fashion trends, seeing more beautiful visual displays, and gaining higher levels of the sense of social approval when shopping at department stores. However, findings reveal no difference between the perception of gaining self-gratification value and social interaction value at those retail outlets, which indicates that Chinese consumers shop at both outlets to socialize with others and/or improve their personal well-being. Because self-gratification and social interaction are two dimensions of hedonic shopping value (Yu & Bastin, 2010), the findings suggest that supermarkets do provide some levels of recreational shopping experiences in the marketplaces. However, department stores provide a broader range of recreational shopping experiences and hedonic shopping value to consumers.

Secondly, although participants perceived significantly higher levels of social status value at department stores, the means of social status value at both retail outlets are relatively low with 3.82 at department stores and 3.40 at supermarkets. This finding is consistent with that of the preliminary qualitative study, which suggests Chinese consumers are less likely to shop to gain social approval and acceptance. Although Chinese consumers do shop to satisfy social needs, their social needs can be very different from those of Western consumers (Davis et al., 2012). Therefore, social status shopping value may only be effective in explaining certain specific Chinese consumers shopping behavior such as mall shopping (Cai & Shannon, 2012) and consumption of luxury goods. Thirdly, participants perceived gaining higher levels of choice value at department stores, which can be explained by the fact that major local department stores are all full-line department stores and some of them even have a grocery store within. On the other hand, participants perceived gaining significantly higher levels of acquisition value, which means that they perceived getting better price value and deals, at supermarkets. They also perceived gaining significantly higher levels of transaction value at supermarkets, which may be explained by more bargain hunting opportunities in supermarkets because of frequent promotions and weekly specials. Furthermore, participants perceived significantly higher levels of efficiency value at supermarkets which also indicates that consumers are more likely to shop at supermarkets to satisfy their needs for everyday products where efficiency is important.

6 CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

With the economic development and improvement of living standards, Chinese consumers are becoming more demanding (Wang et al., 2008). Meanwhile, the development of the Chinese retail industry and the entrance of international retailers have created a very competitive retail environment. To be successful, retailers have to create and deliver value to their consumers, just as in Western markets. Therefore, it is more important than ever for retailers to identify critical shopping value for Chinese consumers and understand the effect of shopping value on their shopping behavior. This study contributes to the literature by exploring key shopping value dimensions for Chinese consumers and their value perception in two most popular retail outlets, department stores and supermarkets, by using the shopping value framework developed by Davis and Dyer (2012). The findings indicate that shopping value has multiple dimensions for Chinese consumers, as it does for Western consumers, which supports Yu and Bastins (2010) findings. They also indicate that majority value dimensions identified in western markets are also applicable to Chinese consumers because of the newly established consumer culture. It is clear that from Chinese consumers perspective, shopping is about satisfying different needs and wants, thus pursuing different shopping value. Rather than just focus on functional value of products, as indicated in earlier studies (e.g. Tse et al., 1989), Chinese consumers emphasize a broad range of shopping value, including hedonic value. Yu and Bastin (2010) concluded that hedonic shopping value has become important for Chinese consumers. The findings of this study provide further evidence that todays Chinese consumers are very likely to shop for fun and experiences, that is, to pursue hedonic shopping value. Like Western consumers, Chinese consumers desire a pleasant shopping experience in the marketplace. Chinese consumers have become more hedonic orientated. Thus, pursuing both utilitarian and hedonic value has become essential to explain Chinese consumers shopping behavior.

On the other hand, the findings also suggest that todays Chinese retail markets do provide a broad range of shopping value to consumers, from those associated with purchasing goods and services, such as choice value, acquisition value, and efficiency value, to those related to hedonic shopping experiences like exploration value, social interaction value and self-gratification value. However, Chinese consumers do experience somewhat different shopping value at department stores versus supermarkets. They experience and perceive gaining more dimensions of hedonic shopping value at department stores, and more dimensions of shopping value that are associated with exchange activity at supermarkets: transaction, acquisition, and efficiency value. But at the same time, they perceived gaining similar levels of socialization value and self-gratification value in both retail outlets, which means that they gained similar hedonic shopping experiences in those retail outlets by socializing with family and friends, releasing stress, improving mood, or treating themselves to something special there. This is quite different from US retail markets where consumers mainly perceived gaining utilitarian shopping value from shopping at mass merchandisers (Davis & Dyer, 2012).

The difference in consumers value perception from shopping at department stores and supermarkets also indicate that those two retail outlets clearly have different marketing positions and value propositions in the local market. That is, department stores deliver a broader range of hedonic shopping value and supermarkets do a better job delivering functional shopping value. To cater to local consumers desire for gaining different value and shopping experiences, these outlets may want to strategize not only to reinforce their key value proposition but also explore other choices. For example, supermarkets, which already deliver good socialization and self-gratification value, may want to emphasize more on satisfying consumers needs for relaxation and socialization by adopting simple strategies such as providing resting areas and adding snack bars, thus enhancing hedonic shopping value for consumers. Department stores, on the other hand, may host special events such as fashion shows and emphasize a more exciting shopping environment to attract more consumers.

7 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE STUDIES

Although this study contributes to our understanding of Chinese consumers shopping value, it has some limitations. This research used a convenience sample; therefore, special care should be taken to generalize the findings to the overall population. Further studies may use other sampling methods such as store intercept and random sampling to further verify the findings. Content-wise, while the study shed light on Chinese consumers value dimensions and value perception in two key retail outlets in China, it did not investigate which value dimensions are more important for consumers shopping at each outlet. Therefore future studies may focus on evaluating the importance of each value dimension at different shopping outlets. Although the findings of the study suggests that many shopping value dimensions identified in the western consumer markets are also applicable for Chinese consumers, future studies may still focus on identifying unique shopping value dimensions for Chinese consumers because of their unique culture and history background. Meanwhile, future research may focus on developing better value measurement scales specific for measuring Chinese consumers shopping value. It is also critical to investigate the effect of shopping value on consumer patronage behavior, such as shopping frequency, expenditure, store choices and retail brand loyalty.

Furthermore, Chinas retail market is highly fragmented. Because of unbalanced economic development and changes in personal values as part of a changing social environment (Zhang, Grigorious, & Li, 2008), Chinese consumers from different regional markets have very distinct shopping and purchasing behaviours (Tse et al., 1989; Cui & Liu, 2000). With the rapid growth of both domestic and international retailers, more retailers would expand aggressively to inland regions (Liu, 2007). However, limited attention has been given to consumers shopping and patronage behaviour in less developed inland China (Tsang, Zhuang, Li, & Zhou, 2003; Liu, 2007). Therefore, it becomes critical to understand consumers in those regional markets. Cross-cultural research comparing Chinese consumers from different regional markets is highly needed, which will shed more light on Chinese consumers shopping behavior and provide more insights for international retailers aiming to enter and expand in Chinese markets. Finally, further studies may want to focus on shopping value theory development because of the constant changes in consumer demand and culture, especially in emerging markets.

REFERENCES

Arnold, M.J., & Reynolds, K.E.. Hedonic shopping motivations[J]. Journal of Retailing, 2003,79(2):77–95.

Babin, B.J., & Attaway, J.S.. Atmospheric affect as a tool for creating value and gaining share of customer[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2000(49):91–99.

Babin, B.J., Darden, W.R., & Griffin, M.. Work and/or fun: measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 1994,20(4):644–656.

Babin, B.J., Lee, Y.K., Kim, E.J., & Greffin, M.. Modeling consumer satisfaction and word-of-mouth: restaurant patronage in Korea[J]. Journal of Services Marketing, 2005,19(3):133–199.

Cai, Y., & Shannon, R..Personal values and mall shopping behavior: The mediating role of intention among Chinese consumers[J]. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 2012,40(4):290–318.

Chan, RYK.. Determinants of Chinese consumers' green purchase behavior[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2001,18(4):389 –413.

Chan, W.K., Perez, J., Perkins, A., & Shu, M.. Chinas retail markets are evolving more quickly than companies anticipate[J]. The McKinsey Quarterly, 1997(2):206 –211.

China Statistical Yearbook[EB/OL]. (2010-06-19). http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2009/indexeh.htm.

Cui, G., & Liu, Q.. Regional market segments of China: opportunities and barriers in a big emerging market[J]. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 2000,17(1):55–72.

Davis, L.. Utilitarian vs. hedonic shopping: Exploring northeast Chinese consumers shopping motivations[R]. Proceeding from the 66th International Textile and Apparel Association #66 proceedings of the international conference,2009.

Davis, L., & Dyer, B.. Consumers value perception across retail outlets – Shopping in mass merchandisers and department stores[J]. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 2012,22(2):115-142.

Davis, L, Peyrefitte, J., & Hodges, N.. From motivation to store choice: Exploring Northwest Chinese consumers shopping behavior[J]. International Journal of China Marketing, 2012,3(1): 71-87.

Dewey, J.. Theory of valuation[M]. In O.Neurath, R.Carnap, and C. Morris (Eds.).Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press,1939.

Grewal, D., Monroe, K.B., & Krishnan, R.The effects of price-comparison advertising on buyers perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions[J]. Journal of Marketing,1998,62(2):46–59.

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L.. Maltivariate Data Analysis [M].6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc,2006.

Holbrook, M.B.. Expanding the ontology and methodology of research on the consumption experience[J]. In D. Brinberg and R.J. Lutz (Eds.), Perspectives on methodology in consumer research,1986: 213–251..

Holbrook, M.B.. The nature of customer value[J]. In R.T. Rust and R.L. Oliver (Eds.), Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice,1994: 21–71.

Hummel, T.J., & Sligo, J.R.. Empirical comparison of univariate and multivariate analysis of variance procedures[J]. Psychological Bulletin, 1971,76 (1), 49–57.

Jones, M.A., Reynolds, K., & Arnold, M.J.. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping value: Investigating differential effects on retail outcomes[J]. Journal of Business Research, 2006(59): 974–981.

Kim, Y.K.. Consumer value: an application to mall and Internet shopping[J]. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 2002,30(12):595–602.

Liu, K.. Unfolding the post-transition era: the landscape and mindscape of Chinas retail industry after 2004[J]. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2007,19( 4):398 –412.

Mai, L.W., & Zhao, H.. The characteristics of supermarket shoppers in Beijing[J]. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 2004,32(1):56–62.

Malhotra, N.K.. Marketing Research – An Applied Orientation[M] .2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall,1996.

Mariampolski, H.. Qualitative Market Research[M]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc,2001.

Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N.K., & Rigdon, E.. The effect of dynamic retail experiences on experiential perceptions of value: an Internet and catalog comparison[J]. Journal of Retailing, 2002,78(1):51–60.

Parasuraman, A.. Reflections on gaining competitive advantage through customer value[J]. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1997,25(2):154 –161.

Parasuraman, A., & Grewal, D.. The impact of technology on the quality-value-loyalty chain: a research agenda[J]. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 2000,28(1):168 –174.

Peter, J.P.. Reliability: a review of psychometric basics and recent marketing practices[J]. Journal of Marketing Research, 1979,16(1):1–17.

Peterson, R.A.. A meta-analysis of Cronbachs coefficient alpha[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 1994,21(2): 381–391.

Rintamaki, T., Kanto, A., Kuusela, H., and Spence, M.T.. Decomposing the value of department store shopping into utilitarian, hedonic and social dimensions: Evidence from Finland[J]. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 2006,34(1):6–24.

Sheth, J.N., Newman, B.I., & Gross B.L.. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values[J]. Journal of Business Research, 1991,22(2):159–170.

Sweeney, J.C., & Soutar, G.N.. Consumer perceived value: the development of a multiple item scale[J]. Journal of Retailing,2001, 77(2):203–220.

Tauber, E.M.. Why do people shop? [J].Journal of Marketing, 1972,36(4): 46–59.

Tai, S.H.C.. Relationship between the personal vlaues and shopping orientation of Chinese consumers[J]. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 2008,20(4):381–395.

Terblanche, N.S., & Boshoff, C.. The in-store shopping experience: a comparative study of supermarket and clothing store customers[J]. South African Journal of Business Management,2004, 35(4):1–10.

Tsang, A.S.L, Zhuang, G., Li, F., and Zhou, N., A comparison of shopping behavior in Xian and Hong Kong malls: utilitarian versus non-utilitarian shoppers[J]. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 2003,16(1):29–46.

Tse, D.K., Belk, R.W, & Zhou, N.. Becoming a consumer society: a longitudinal and cross-cultural content analysis of print ads from Hong Kong, the Peoples Republic China, and Taiwan[J]. Journal of Consumer Research, 1989(15): 452–472.

Uncles, M.D., & Kwok, S.. Patterns of store patronage in urban China[J]. Journal of Business Research,2009,62(1): 68 –81.

US-China Business Council. Gansu province[J]. China Business Review, 2002(29):17–23.

Wang, C.L., Chen, Z.X., Chan, A.K.K., & Zheng, Z.C.. The influence of hedonic values on consumer behaviors: An Empirical Investigation in China[J]. Journal of Global Marketing, 2000,14(?):168-186.

Wang, G., Li, F., & Liu, X.. The development of the retailing industry in China: 1981-2005[J]. Journal of Marketing Channel, 2008(15):145–166.

Westbrook, R.A., & Black, W.C.. A motivation-based shopper typology[J]. Journal of Retailing, 1985,61(1):78–103.

Wong, A., & Dean, A.. Enhancing value for Chinese shoppers: The contribution of store and customer characteristics[J]. Journal of retailing and consumer services, 2009,16(2):123 –134.

Xiao, G., & Kim J.O.. The investigation of Chinese consumer values, consumption values, life satisfaction, and consumption behaviors[J]. Psychology & Marketing, 2009,26(7): 610 –624.

Yu, C., & Bastin, M.. Hedonic shopping value and impulse buying behavior in transitional economies: A symbiosis in the mainland China marketplace[J]. Journal of Brand Management. 2010,18(2):105–114.

Zeithaml, V.A.. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence[J]. Journal of Marketing, 1988,52(3): 2–22.

Zhang, J.. Retailers battle new competitors[J]. Business Beijing, 2004,99(10):16–19.

Zhang, X., Grigoriou, N., & Li, L.. The myth of China as a single market: the influence of personal value differences on buying decisions[J]. International Journal of Market Research, 2008,50(3):377–402.