Evolution of forest cover in Portugal: A review of the 12th –20th centuries

2014-04-20FernandoReboredoJoPais

Fernando Reboredo • João Pais

Introduction

In Europe and North America, less than 1% of all temperate deciduous forests remain undisturbed, free of logging, grazing or other intensive uses. In Europe, massive conversion of forest into agricultural areas occurred during the Pre-industrial period (from the Middle Ages until the middle 17th century). In eastern North America, deforestation migrated westward with agricultural settlement from the 1600s to the middle 1800s (Reich and Frelich 2002).

No doubt the forest cover of the Iberian Peninsula, where the Portugal mainland is located, was affected by inhabitants over the centuries. During the Holocene settlers used wood, charcoal, fire, and converted forests or shrublands into agricultural areas (Daveau 1988). Successive forest use by the Romans (Devy-Vareta 1985) and Arab occupations affected forest cover, the latter for more than four hundred years (Garcia 1986).

Rego (2001) reported that the evolution of forest cover over the last thousand years on the Portuguese mainland followed a pattern common to all Mediterranean countries: natural forest was cleared by frequent fires to favor pasture, the best soils were farmed for cereals, and timber was used for processed materials, fuel and construction.

In Portugal the first dynasty began in the 12th century with King Afonso Henriques (1143-1185) and was extended up to the 14th century. Despite protective measures the exploitation of the forest was never stopped. Throughout the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries forests were continuously felled mainly due to national maritime expansion and associated shipbuilding. Wood was imported largely from Galicia and Asturias, the British Isles (Moreira 1984), Hanseatic League or even Madeira Island (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992).

The crisis of the naval construction worldwide in the 17th century was caused by the scarcity of timber. This caused the price of a new vessel to triple during the 16th century (Costa 1997). The intense corsair activities caused irreversible damage to sea trade and the fleet in general. From the 18th century onward the main goal was to reverse the losses of Portuguese forest cover using practical measures based on laws that favored increases in forest area. These measures were implemented despite the population increase from about 1 million in 1636 to approximately 3 million in 1801, and to 5 million in 1900 (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992).

Similar growth was seen in the world population. From 1650 to 1850, human numbers doubled from about 600 to 1200 million (Malanima 2006) and this increased the pressure on agrarian systems. Woodland and pastures were being converted into arable land to grow potatoes in northern Europe and maize in the South. Similar changes on the Portugal mainland have led to several evaluations of total forest which shrank during the 17th–18th centuries to 7.19% of the land area (Ribeiro and Delgado 1868) or only 3% of the national land area (Fernow 1907).

In general, only in the last quarter of the 19th century was Portugal’s forest loss reversed by the implementation of reforestation programs. The 20th century saw a marked increase in the area of “montado” ie., Quercus suber and Quercus rotundifolia, and above all, a huge expansion of Eucalyptus globulus on the Portugal mainland. In a similar manner, silvicultural management has altered temperate deciduous forests throughout Europe - native species have been replaced by Scotch pine or Norway spruce monocultures or even deciduous mixed forests dominated by Fagus sylvatica (European Environment Agency 2006).

The aim of the present work is to describe the evolution of and the main impacts on forest cover of the Portuguese mainland from the 12th century until the end of the 20th century, based largely on the demographic changes and maritime expansion.

Methods

We used data from palaeo-ecological, archaeological, historical and forestry studies to conduct a critical analysis of the factors that contributed to deforestation. Demography data (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992; Sousa 1997) were used to access the consumption of wood mainly for fuel. This evaluation was based on a consumption rate of 1.1 m3/person/year (Gunes and Elvan 2005) and assuming that the increment and the losses of the Portuguese mainland population were constant in each year. The deforestation rates for every increase of 10% in the mainland population were studied taking into account the minimum and maximum deforestation rates observed in England (Saito 2009). We calculated the amount of wood needed for railroad construction using standard dimensions for railway sleepers (Cruz, http://adfer.cp.pt/ferxxi/ed21/pdf/05.pdf): 2.80 × 0.26 × 0.13 m for wide gauge rail (Iberian standard - 1668 mm) and 1.85 × 0.24 × 0.12 m for narrow gauge rail (Metric standard – 1000 mm). Construction of wide gauge rail requires 1667 railway sleepers per km (See www.refer.pt/MenuPrincipal/TransporteFerroviario/Lexico.aspx ) although no data are given for narrow gauge rail.

Timber export data appear only in the 19th century. The scarcity of timber was a constant for mainland Portugal and timber was imported from various markets leading to a permanent trade deficit. We adjusted data for fuel-wood consumption and population using linear regression analysis and we calculated coefficients of determination (R2). A value of p <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Relationships between forest decline, maritime expansion and sea trade

Portugal’s forests in the 12th century were dominated by the Fagaceae family with species including Quercus faginea, Quercus robur, Quercus pyrenaica, Q. suber, Quercus rotundifolia and Castanea sativa. Elements from the late Laurisilva also remained, including, for example, Laurus nobilis L. and Prunus lusitanica L. Pine forests were also spread all over the mainland particularly Pinus pinea, and to a lesser extent Pinus pinaster and Pinus sylvestris. Other conifers were also found at high elevations, such as Taxus spp and Juniperus communis.

Although species of Pinus and Quercus dominated the landscape, palynological evidences revealed the presence of other genera such as Betula, Corylus, Alnus, Populus, Salix and Myrica (Pais 1989). Agricultural activities were common in the 12th–13th centuries as indicated by the presence of Vitis sylvestris, Ficus carica, Morus, Prunus cerasus, Prunus domestica, Prunus persica, Punica granatum, Juglans regia and Olea spp (Pais 1989; 1996). In this epoch, the lands belonged to the monarchy and to several religious orders and nobles by donation.

During the Middle Ages (c. 500-1500 AD), kings progressively ceded control of forests to nobles, churches, monasteries and, later on, local communities and communes (Wickham 1990). Forests were no longer viewed as places where the king and nobles enjoyed recreational activities (e.g. hunting), but rather as sources of non-wood forest products (mushrooms, berries, acorns, chestnuts, wax, resin) and raw-materials that increased the income of the crown, i.e. protection was progressive replaced by exploitation.

Due to Portugal’s long coastline, maritime trade and fisheries were important drivers of the national economy of the 12th century. In 1312, during the reign of King Dinis (1279-1325), a permanent naval force was established to defend the mainland and maritime routes from attacks, while the first attempts at Atlantic expansion occurred in 1336 and 1341 (Marinha http://www.marinha.pt/pt/amarinha/historia/historiadamarinha/pa ges).

During the 14th century the demand for wood from the mainland increased steadily, precluding the regeneration of Portuguese forests (Devy-Vareta 1986) and leading to timber imports from several sources. For example, the links between Portugal and the Hanseatic League (HL) were strengthened during the 15th century although the direct relationship began as early as 1373. In exchange for Portugal’s salt, exporters offered cereals, wood and other products from northern Europe. As the trade developed, cork, wine and olive oil were also sold by Portugal (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992).

The conquest of Ceuta in 1415, a city on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, by a Portuguese armada triggered the discovery travels. The vessel with the key role in the discoveries in the 15th century, the so-called “Caravela” or “Caravela Latina”, had, on average, 50 toneis1Capacity measure used in ancient naval construction.of capacity (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992), as compared to the ships of the 16th century that had capacities reaching 400-600 toneis, typical of the vessels sailing to India (Domingues 2004). Thus, the amount of wood used to construct a ship depended on the size of the ship and the size of trees felled to produce the wood. Lourenço (1990) reported that the construction of a cargo ship for long-distance trade required 2 to 4 thousand large trees.

Overseas trade with India, Africa, Brazil and China, increased rapidly with the discoveries. Guinote (2003) reported that 1154 vessels sailed from Lisbon to India between 1497 and 1700. The losses attributed to wreckage or corsair attacks were near 20% while the percentage of successful returns to Lisbon was 51%. The remaining percentage included vessels that remained in the Indic Ocean for defensive and trade purposes. At least 2000 vessels were needed for the Brazil, India and North-Africa campaigns, although this number might have reached 2500. If at least 2000 trees were used to build each vessel and considering the number of ships involved in maritime expansion, we estimate that approximately 4 to 5 million trees were felled during the maritime expansion, mainly P. pinea, Q. suber, Q. rotundifolia and to a lesser extent P. pinaster.

The deforestation of the Portuguese mainland – national defense and exploration.

The need for wood in shipbuilding was the key driver of deforestation but industrial activities and demographic expansion also contributed to forest loss. The preferred woods for shipbuilding were the above-listed species but Q. robur, Q. faginea and Castanea sativa were also used. Moreover, the perception of the consequences of excessive wood consumption lead Afonso III (1248-1279) to implement the first documented large-scale reforestation in the world in the 13thcentury (Pinhal de Leiria) and this was concluded by King Dinis (1279-1325).

A letter from King Dinis dated 1310 established penalties for those who felled trees in Campo de Ourique - south of Portugal (Baeta-Neves 1980). Another letter (1471) from Afonso V (1438-1481) forbade the removal of wood or bark and the manufacturing of charcoal in Algarve (south of Portugal) for export (Baeta-Neves 1982), which was seen as an attempt to slow the expansion of the Spanish fleet (Magalhães 1970). Furthermore, King Afonso V, a hunting enthusiast strictly enforced laws banning poaching and theft of wood and firewood (Rebello da Silva 1868).

The need for wood was so great that a royal letter dated 1474 allowed felling of trees in areas belonging to the church i.e., surrounding the monasteries (Devy-Vareta 1986). Despite some protective measures, King Manuel I (1495-1521) allowed the use of charcoal from Quercus suber in the production of soap in the counties of Santarém, Abrantes and Torres Novas (Baeta-Neves 1983).

Portugal’s kings clearly understood the importance of the maritime trade, especially in those regions recently discovered, and strongly encouraged shipbuilding. King Manuel I gave orders in 1502 to expand the old S. Bento shipyard in Viana. However, this measure was not implemented due to the scarcity of wood. In 1517, farmers near Viana were obliged to plant four trees each year on their own lands preferentially Quercus, Castanea, Juglans and Salix (Moreira 1984), indicating the depletion of the forest cover at that time.

An important landmark in Portuguese forestry was the “Trees Law” in 1565 whose main purpose was the reforestation of communal and private lands using species of Pinus, Quercus and Castanea. This measure was administered by municipalities that established forest stands, and specified the numbers of trees to plant and undertook monitoring and enforcement.

During the 16th century threats increased to the maritime borders of the mainland as did attacks on the recent possessions, by French, English and Arab corsairs (Magalhães 1997). A crisis in ship construction in the 17thcentury emerged across maritime Europe. Wood was scarce and the cost of a new ship tripled during the 16th century while the longevity of the vessels declined (Costa 1997). For example, ships sailing the Cape of Good Hope remained active on average two to three years as compared to eight years during the earlier travels. This was mainly due to the use of poorly-dried wood and the decline of the quality and abundance of trees. Thus, conservation was critical because of the time required for trees to reach commercial maturity, similar to the situation today for users of timber from increasingly rare and endangered tree species.

Other factors involved in the forest decline

Demographic expansion

Demographic expansion in the mainland was also a key issue driving deforestation. Wood was increasingly used for the construction of houses, vineyards and other agricultural activities, for heating and was used in food processing.

Estimates based on the number of hamlets on the mainland (Sousa 1997) showed that the number of inhabitants was approximately constant between 1300 and 1348 at 1.5 million. From 1348 to 1349 a sharp decline of half a million inhabitants was followed by another decline of 150,000 between 1350 and 1450. These declines were simultaneous with others verified in France (Morin 1996) or England (Henderson-Howat 1996) and were caused by mortality due to plague that spread all over Europe.

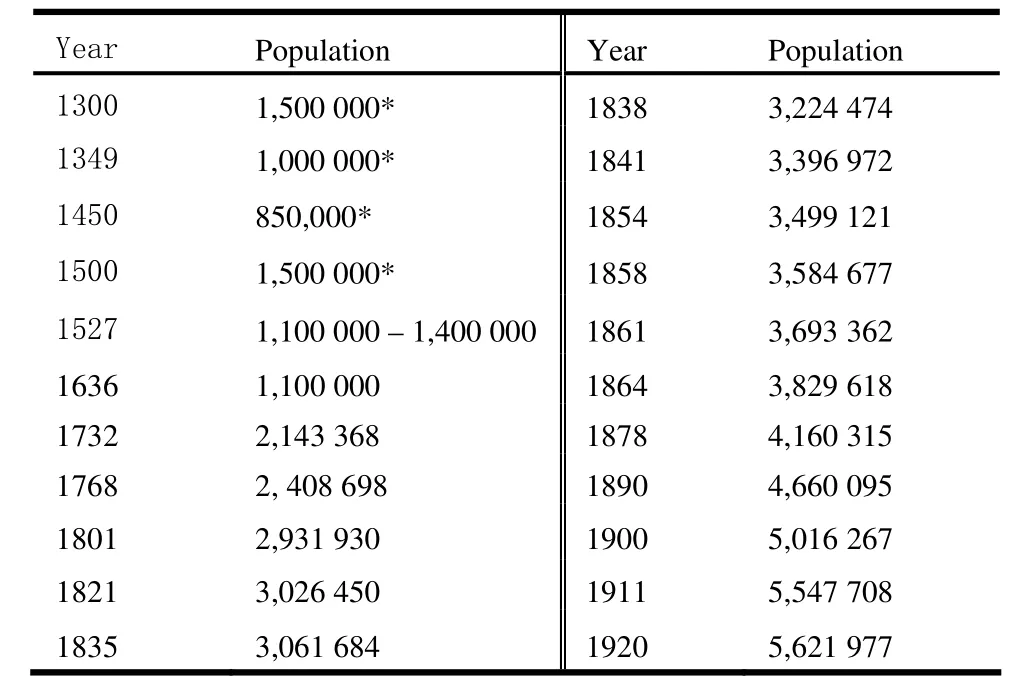

From 1451 onwards the Portuguese population began to recover, reaching 1.5 M in the early 16th century (Sousa 1997). In the first quarter of the 16th century (1527) Portugal had 1.1-1.4 M inhabitants while between 1527 and 1636 the mainland population was approximately constant. From 1636 onwards until 1854 the population increased to 2,399,121 inhabitants – Table 1 (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992).

Assuming that the increment and the losses of the Portuguese mainland population were constant in each year (exception during the Black Death period), several calculations were performed. The increase of 110052The number was obtained by dividing the increment of the mainland population, between 1636-1854, by the number of years within these dates.inhabitants each year from 1636 until 1854, matches published results (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992). Thus, taking into account both increments and losses, we calculated the consumption of fuel-wood each year assuming a consumption rate of 1.1 m3per person per year (Gunes and Elvan 2005). For expediency reasons we considered the population to be stable between 1300 and 1348 (1.5 million inhabitants) and between 1527 and 1636 (1.1 million inhabitants). The calculation of wood consumption between 1501 and 1526 was based on the difference between the last data of Sousa (1997) and the first data of Dicionário de História de Portugal (1992).

Table 1: Demographic evolution in Portugal mainland.

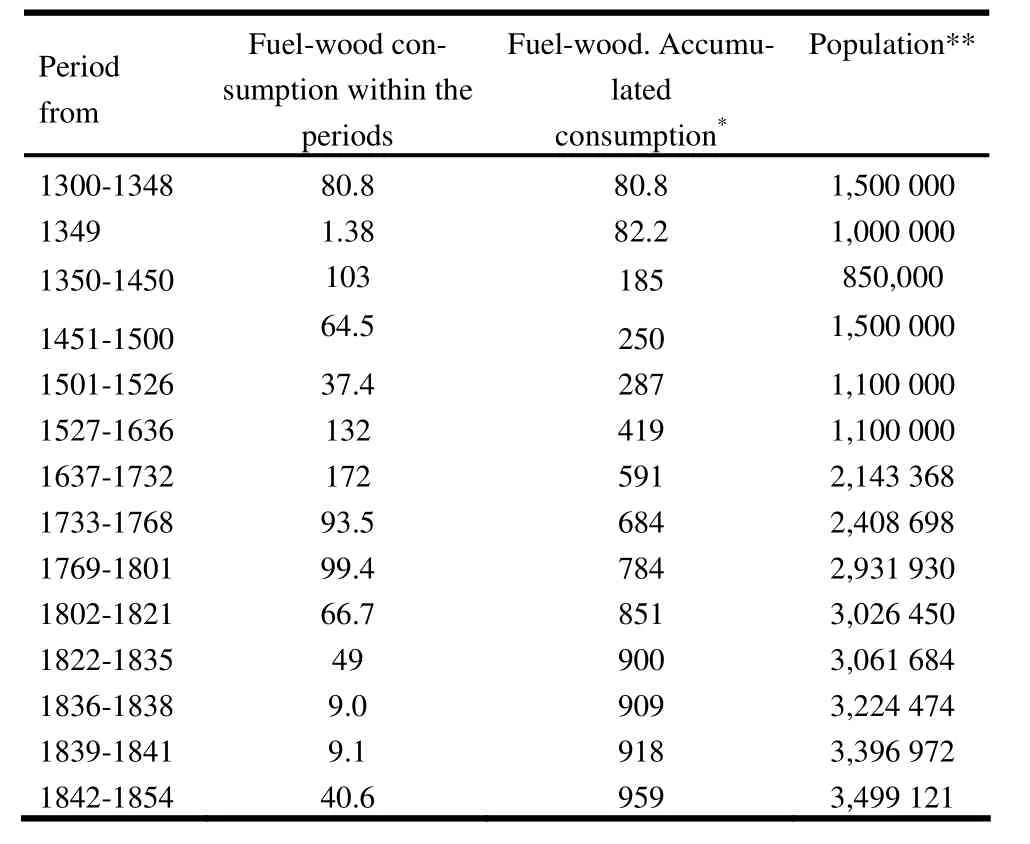

We estimated cumulative consumption of 959 Mm3between 1300 and 1854 (Table 2). Some important climatic events that occurred within this period such as the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age were not taken into account, although we may infer that the position of the mainland bordering the Atlantic, and the strong Mediterranean influences and the disposition of the Pyrenees Chain created mild winters with favorable conditions for human occupation. Furthermore, the annual consumption per capita, measured by volume, might have varied with the type of wood used and its quality, the efficiency of the consumption and the heating needs in each year (Warde 2006).

Table 2: Evolution of the fuel-wood consumption versus population in Portugal mainland

When cumulative fuel-wood consumption data were plotted against population data on the mainland, a significant correlation (p <0.05) was observed (R2= 0.8997), indicating that when the population increases so does the fuel-wood consumption (Fig. 1). When we considered fuel-wood consumption versus population size up to 1636, a very low R2value was obtained (0.0131). Conversely, when we considered data from 1637 onwards, a highly significant correlation (p <0.01) was verified (R2= 0.9605). These findings indicate two distinct phases. The first one related to demographic fluctuations within a narrow band between 1.5 million and 1.1 million inhabitants, and the second related to a demographic boom reaching 5.0 million at the start of the 20th century.

Fig. 1: Million inhabitants versus accumulated fuel-wood consumption (Mm3), within the periods referred in Table 2.

Assuming the deforestation rates observed in the UK – a minimum of 3.3% and a maximum of 5.4% for every increase of 10% in the population (Saito 2009), we estimate deforestation rates between 1636 and 1854 of 72.6% and 96%, respectively, indicating an extreme degradation of national forest cover. The choice of the UK rates instead of the French rates was mainly based on the national population of the UK, which is more similar to that of Portugal. For example, in 1350, England had 4 million inhabitants (Henderson-Howat 1996), France had 21 million in 1300 (Morin 1996), while Portugal had 1.5 million in 1300 (Sousa 1997). Few countries have demographic data from that period and some of the EU countries of today either did not yet exist or had different borders.

Ribeiro and Delgado (1868) reported that in the 18thcentury mainland Portugal reached its highest degree of deforestation at a forested area of 7.19% of the total area and farmland covering 21.16% of the total, the latter increasing to 34.91% by 1902 (Vieira 1991). Deforestation rates were not calculated for the period 1300-1450 when the population declined due to the Black Death, or for the period 1451-1527 when the population had recovered from the Black Death and forest cover again declined.

Although it is common to conclude that woodland area increased when the population declined (Malanima 2006; Saito 2009), this did not happen on mainland Portugal because the fluctuations in demography were coincident with the maritime expansion and the huge increment of naval shipyards and the increasing number of new settlers in recently discovered lands. Our analysis was not extended beyond 1854 since afforestation/reforestation programs were implemented in the early 19th century in the mobile sands of the Couto de Lavos (Andrada e Silva 1969) and from 1850 onwards in the dune string along the coastline and later in the higher mountains of the inland.

Railway construction

The construction of the railway which began in the middle 19th century exerted heavy pressure on mainland forests. The first link between Lisbon and Carregado was initiated in 1856 and the connection with Spain in 1863 (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992). In the last half of the 19th century more than 2000 km of railway were built (Table 3), requiring a large volume of wood for railway sleepers. If we take into account the standard measures we conclude that each km needed 158 m3of wood for wide guage rail, or 88 m3for narrow guage. Within the 35 years between 1877-1912, 2974 km of rail were built, using a minimum of 261,712 m3of wood for a fully narrow track or a maximum of 469,892 m3for a fully wide track (Reboredo and Pais 2012).

Table 3: Evolution of the number of railway km constructed

We cannot be certain about the species of timber used for railway sleepers, but oak was most likely the main raw-material. A report from 2001 (Conselho Nacional do Ambiente e do Desenvolvimento Sustentável 2001) stated that the Industrial Revolution and the beginning of railway construction contributed to the destruction of the remaining oak forests. This was confirmed by Paiva (2003) who claimed that timber from Q. pyrenaica was used to produce railway sleepers. Surviving wooden sleepers in Portugal were made from P. pinaster wood, the most abundant forestry species in Portugal during the 20th century.

Reforestation. An urgent need or an aware action?

As previously stated, Portugal reached its highest degree of deforestation in the 18thcentury at a time when farmland and vineyards increased in area (Ribeiro and Delgado 1868). In 1805 Andrada e Silva began his work to restore and reforest the mobile sands of the Couto de Lavos through the seeding of Pinus, Artemisia crithmifolia L., Ulex, Cytisus, Spartium, Ammophila arenaria L. and Phragmites, among others (Andrada e Silva 1969). In 1824 the General Administration of Crown Woodlands was created under the supervision of the Ministry of the Navy, while the Forestry Services were launched in 1886. The Forestry Services were responsible for the beginning of the reforestation programs in Gerês and Estrela mountain ranges in parallel with the establishment, in the early 20th century, of the so-called Forestry Regimen, a set of laws that allowed the intervention of the state at a large-scale in the expansion of forest area and forest management, of private and communal lands and on state lands.

Radich and Baptista (2005) estimated that between 1875 and 2005 the forested area in mainland Portugal increased from 7% to approximately one third. It is believed that between 1875 and 1938 the forested area grew to 1.8 million ha mainly through the action of private owners. In the Central and Northern areas, forest area expanded due to plantation of Pinus, while in the South, growth was due to increase in the coverage of “montado” i.e., Qu. suber and Q. rotundifolia.

Despite all the efforts, Portugal suffered a permanent deficit of timber (Table 4), mainly due to the manufacturing of barrels to supply the emerging trade in Madeira and Port wines. For example, timber imports between 1870 and 1879 expressed in escudos (Portuguese currency of the day), were four times higher than were exports in the same period. Although timber exports have increased during the twentieth century, the deficit remains (Dicionário de História de Portugal 1992).

Table 4: Imports and exports of manufactured and raw wood

The Afforestation Plan dated 1938 was intended to conclude the afforestation of dunes (14500 ha), the reforestation of communal lands north of the Tagus river (420,000 ha), the foundation of several forestry administrations, and the building of considerable infrastructure. This Plan was based on the extreme degradation of soils in the mountain areas due to deforestation, overgrazing, fire and rye culture (Germano 2004). The Suber3From Quercus suberDevelopment Plan dated 1954, initiated an expansion campaign through the plantation of Q. suber on lands south of the Tagus River, which resulted in an occupation of non-traditional areas such as the southeast of Alentejo and Algarve. This initiative left for the following generations an important economic resource, cork, a raw-material for which Portugal is the main world producer and exporter.

Throughout the 20th century the landscape was dominated by four species (P. pinaster, Q. suber, Q. rotundifolia and Eucalyptus globulus). The area occupied by P. pinaster and to a lesser extent Q. rotundifolia, has been decreasing while the areas of Q. suber and E. globulus have been increasing with the later showing a large increment (Table 5). This shows a poor species composition and a relatively constant land area use in terms of hectares.

Table 5: Evolution of the forest occupation according the different National Forest Inventories.

According to the 1995-1998 National Forest Inventory, the forest area in the Portuguese mainland amounted to 3200 × 103ha, approximately 36% of the total area. P. pinaster was by far the predominant forest tree, covering 976,000 ha. Quercus suber ranked second at 713,000 ha and finally E. globulus at 672,000 ha (Table 5), corresponding to 30.5%, 22.3% and 21%, of the forest area, respectively (Autoridade Florestal Nacional 2010). The area of E. globulus increased 6.8-fold, from the middle 1960s until the last forest inventory in the 20thcentury. This increment was mainly due the Portuguese Forestry Project/World Bank which began in 1980. The main objective was to plant 150,000 ha of E. globulus before 1986 to supply the pulp and paper industry. Currently, the paper, paperboard and wood pulp industries are responsible for sales of more than 2000 million Euros while the cork-based trade is valued at 762 million Euros (INE 2012). Furthermore, the last National Forest Inventory dated 2010 revealed that E. globulus reached, for the first time, the top rank in terms of occupied area at 812,000 ha while Q. suber ranked second at 736,000 ha (IFN6 2013.

Conclusions

Since the beginning of the nation in the 12th century, forests were continuously felled although the strong contribution to deforestation had its origins in the maritime expansion especially in the 15th and 16th centuries when approximately 5 million trees were felled, mainly of Pinus and Quercus species.

As expected, forests did not regenerate at the same rate at which naval vessels were built. Thus, the monarchy tried to balance need or consumption with conservation by the approval of restrictive laws for particular types of industries in order to spare wood for shipyards. The import of wood from several origins was the solution to overcome the problem.

At the same time the demographic expansion put tremendous pressure on forest resources particularly from 1636 onwards. How many million cubic meters of fuel-wood were used each year by the Portuguese families at that time? We do not know exactly but when analyzing recent data in which poverty dominates and by making careful extrapolations, the results are surprising. An accumulated fuel-wood consumption of 672 Mm3by the mainland inhabitants was needed for survival between 1527 and 1854, i.e., in a 327 year period. The deforestation rates for every increase of 10% in the mainland population between 1636 and 1854, reached a minimum of 72.6% and a maximum of 96%, indicating extreme degradation of national forest cover, and on other hand, showing that before 1636 population increase was not the main driver of deforestation, but rather it was the massive naval ship construction program.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to Dr. Thomas Dahmer (USA) and Dr. Alan Phillips (UK), for the accurate revision of the manuscript the suggestions and remarks.

Autoridade Florestal Nacional. 2010. 5.º Inventário Florestal Nacional. Apresentação do Relatório Final (5th National Forest Inventory. Final Report Presentation). Setembro, p.14.

Andrada e Silva JB. 1969. Memória sobre a necessidade e utilidades do plantio de novos bosques em Portugal (Memo about the need and utility of planting new forests in Portugal). 2ª Edição, Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, p.171.

Baeta-Neves CML. 1980. História florestal, aquícola e cinegética. Colectânea de documentos existentes no Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo. (History of forestry, freshwater and hunting. Document collection existing in the National Archives of Torre do Tombo). Chancelarias Reais. Ministério da Agricultura, Florestas e Alimentação, Vol. I, Lisboa, p.316.

Baeta-Neves CML. 1982. História florestal, aquícola e cinegética. Colectânea de documentos existentes no Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (History of forestry, freshwater and hunting. Document collection existing in the National Archives of Torre do Tombo). Chancelarias Reais. Ministério da Agricultura, Florestas e Alimentação, Vol. II, Lisboa, p. 257.

Baeta-Neves CML. 1983. História florestal, aquícola e cinegética. Colectânea de documentos existentes no Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (History of forestry, freshwater and hunting. Document collection existing in the National Archives of Torre do Tombo). Chancelarias Reais. Ministério da Agricultura, Florestas e Alimentação, Vol. IV, Lisboa. p.342.

Conselho Nacional do Ambiente e do Desenvolvimento Sustentável. 2001.“Reflexão sobre a sustentabilidade da política florestal Nacional”Relatório de Trabalho (Reflexion about the sustainability of the national forest policy. Work report), p.100.

Costa LF. 1997. A indústria. A construção naval. In: História de Portugal. No alvorecer da Modernidade (The industry. Shipbuilding. In: Portugal’s history. At the dawn of modernity) vol III (Coordenação J.R. Magalhães), Editorial Estampa, Lisboa, pp. 261-278.

Cruz S. 2012. Elementos constituintes da superestrutura da via (The components of the track superstructure). Refer, Engenharia de Infraestruturas, 5-14. Available at: http://adfer.cp.pt/ferxxi/ed21/pdf/05.pdf. [Assessed March, 2012]

Daveau S. 1988. Notas e Recensões. Progressos recentes no conhecimento da evolução holocénica da cobertura vegetal em Portugal e nas regiões vizinhas (Recent progress in the knowledge of the Holocene evolution of the forest cover in Portugal and neighbour regions). Finisterra ( Lisboa), XXIII, 45: 101-115.

Devy-Vareta N. 1985. Para uma geografia histórica da floresta Portuguesa. As matas medievais e a “coutada velha” do rei (For a historical geography of the Portuguese forest. Medieval forests and king’s old hunting ground) . Revista da Faculdade de Letras – Geografia, I Série, Vol. I, Porto, 47-67.

Devy-Vareta N. 1986. Para uma geografia histórica da floresta Portuguesa. Do declínio das matas medievais à política florestal do Renascimento (Séc. XV e XVI) (For a historical geography of the Portuguese forest. From the decline of medieval forests to the forest policy of Renaissance). Revista da Faculdade de Letras – Geografia, I Série, Vol. I, Porto, 5-37.

Dicionário de História de Portugal. 1992. Vols. I-IV, dirigido por Joel Serrão, Livraria Figueirinhas (Porto).

Domingues FC. 2004. Os navios do mar oceano. Teoria e empiria na arquitectura naval Portuguesa dos séculos XVI e XVII (Ocean vessels. Theory and empirism in the Portuguese navy’s architecture in 16th and 17th centuries) , Lisboa, Centro de História da Universidade de Lisboa.

European Environment Agency. 2006. European forest types, European Environment Agency, Technical Report nº 9, Copenhagen, 111 pp

Fernow BE. 1907. History of Forestry in Europe, the United States and other countries. University Press, Toronto, Ontario, 464 pp

Garcia JCS. 1986. O Espaço medieval da reconquista no sudoeste da Península Ibérica (The medieval space of the reconquest of the southwest of Iberian peninsula). Lisboa. Centro de Estudos Geográficos. Col. Chorographia, Série Histórica - Estudos e Documentos Comentados, nº 2, 130 pp.

Germano MA. 2004. Regime Florestal. Um Século de Existência (Forestry regimen. A century of existence). Direcção Geral dos Recursos Florestais. Lisboa, p.167.

Guinote P. 2003. India Route Project: Ascensão e Declínio da Carreira da Índia (Rise and decline of India route), World Wide Web, URL, http://nautarch.tamu.edu/shiplab/, Nautical Archaeology Program, Texas A&M University.

Gunes Y, Elvan OD. 2005. Illegal logging activities in Turkey. Environmental Management, 36: 220-229.

Henderson-Howat DB. 1996. Great-Britain. In: Long-term historical changes in the forest resource. Chapter 4, 23-26. Geneva Timber and Forest Study Papers Nº 10, UNECE/FAO, p.65.

IFN6, 2013. 6º Inventário Florestal Nacional. Áreas dos usos do solo e das espécies florestais de Portugal continental. Resultados preliminares, (6th National Forest Inventory. Areas of soil and forestry species uses in mainland Portugal. Preliminary results) Fevereiro 2013, Ministério da Agricultura, do Mar, do Ambiente e do Ordenamento do Território, Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas.

INE. 2012. Estatísticas Agrícolas 2011 (Agricultural Statistics 2011). INE, I.P., Lisboa, Portugal, 170 pp.

Lourenço C. 1990. A floresta Portuguesa e os descobrimentos marítimos. (Portuguese forest and the maritime discoveries) Academia da Marinha. Lisboa. p.11.

Magalhães JAR. 1970. Para o estudo do Algarve económico durante o século XVI (For the study of economic Algarve during the 16th century), Edições Cosmos, Lisboa, p.288.

Magalhães JR. 1997. O enquadramento do espaço nacional. In: História de Portugal. No alvorecer da Modernidade (1480-1620) (The framework of the national territory. In: Portugal’s history. At the dawn of modernity, 1480-1620) Vol III (Coordenação J.R. Magalhães), Editorial Estampa, Lisboa, pp.19-59.

Malanima P. 2006. Energy crisis and growth 1650-1850: the European deviation in a comparative perspective. Journal of Global History, 1: 101-121.

Marinha The Navy story. Available atL http://www.marinha.pt/pt/amarinha/historia/historiadamarinha/pages. [Assessed February 2012]

Moreira MAF. 1984. O porto de Viana do Castelo na época dos descobrimentos (Viana do Castelo harbour in the epoch of the discoveries). Edição da Câmara Municipal de Viana do Castelo. 172 pp.

Morin GA. 1996. France. In: Long-term historical changes in the forest resource. Chapter 3, 19-22. Geneva Timber and Forest Study Papers Nº 10, UNECE/FAO, 65 pp.

Pais J. 1989. Evolução do coberto florestal em Portugal no Neogénico e no Quaternário (Forest cover evolution in Portugal during the Neogene and Quaternary). Comunicações dos Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, 75: 67-72.

Pais J. 1996. Paleoetnobotânica (finais séc. XI a séc. XIII-XIV) do Sul de Portugal – Setúbal, Mértola e Silves (Palaeo-ethnobotany of south of Portugal – Setúbal, Mértola and Silves). Arqueologia Medieval, Mértola, 4: 277-282.

Paiva J. 2003. A floresta Portuguesa. (I) História da Silva Lusitana. (The Portuguese forest. Lusitanian Silva history) Floresta e Ambiente, 62: 15-17.

Radich MC, Baptista FO. 2005. Floresta e sociedade: Um percurso (1875-2005) (Forest and society. A route, 1875-2005). Silva Lusitana, 13: 143-157.

Rebello da Silva LA. 1868. Memória sobre a população e a agricultura de Portugal: Desde a fundação da monarquia até 1865 (Memo about the population and agriculture in Portugal. From monarchy foundation until 1865). Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, p.335.

Reboredo F, Pais J. 2012. A construção naval e a destruição do coberto florestal em Portugal. Do século XII ao século XX (Shipbuilding and destruction of forest cover. From 12th to 20th centuries). Ecologia (Revista online da Sociedade Portuguesa de Ecologia), 4: 31-42.

REFER (www.refer.pt/MenuPrincipal/TransporteFerroviario/Lexico.aspx) Assessed March, 2012.

Rego FC. 2001. Florestas Públicas (Public Forests). Direcção Geral das Florestas/Comissão Nacional Especializada de Fogos Florestais, Lisboa, p.105.

Reich PB, Frelich L. 2002. Temperate deciduous forests. Vol. 2 “The earth system: biological and ecological dimensions of global environment change”. In: H.A. Mooney and J.G. Canadell (eds), Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change. pp. 565-569.

Ribeiro C, Delgado JFNE. 1868. Relatório àcêrca da Arborização Geral do Paiz (Report about the General Arborization of the country), Ministério das Obras Publicas, Commercio e Industria. Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias, Lisboa.

Saito O. 2009. Forest history and the great divergence: China, Japan and the West compared. Journal of Global History, 4: 379-404.

Sousa A. 1997. Condicionalismos Básicos. In: História de Portugal. A Monarquia Feudal (1096-1480) (Basic constraints. In: Portugal’s history. The feudal monarchy, 1096-1480) Vol II (Coordenação J. Mattoso), Editorial Estampa, Lisboa, pp. 263-326.

Vieira JAN. 1991. Arborização e desarborização em Portugal (Arborization and deforestation in Portugal). DGF Informação, 8: 9-15.

Warde P. 2006. Fear of wood shortage and the reality of the woodland in Europe, 1450-1850. History Workshop Journal, 62: 29-57.

Wickham C. 1990. European forests in the early middle ages: Landscapes and land clearance. Paper presented at the XXXVII Settimana di Studio del Centro Italiano sull’Alto Medioevo, 30 March-5 April 1989, Spoleto: pp.479-545.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Carbon sequestration in Chir-Pine (Pinus roxburghii Sarg.) forests under various disturbance levels in Kumaun Central Himalaya

- Regional differences of water conservation in Beijing’s forest ecosystem

- Spatial modeling of the carbon stock of forest trees in Heilongjiang Province, China

- Spatial heterogeneity of factors influencing forest fires size in northern Mexico

- Community ecology and spatial distribution of trees in a tropical wet evergreen forest in Kaptai national park in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh

- Diversity, regeneration status and population structure of gum- and resin-bearing woody species in south Omo zone, southern Ethiopia