Accruals:An overview

2014-02-22JamesOhlson

James A.Ohlson

Stern School of Business,NYU,United States Cheung Kong GSB,China

Accruals:An overview

James A.Ohlson

Stern School of Business,NYU,United States Cheung Kong GSB,China

A R T IC L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 8 M arch 2014

Accep ted 8 M arch 2014

Availab le online 26 Ap ril 2014

Accruals

The paper p rovides a broad discussion o f the topic“accruals”.Thoughmuch of w hat is said is fam iliar from the literatu re on accruals,the paper tries to develop concep ts and show how theses forge tight links across a variety of themes.The starting pointo f theanalysis concerns the construct of an accrual. The case is made that it shou ld rest so lely on consecutive balance sheets and the sp litting of assets/liabilities into(i)cash and app roximate cash, assets/liabilities and(ii)all other kinds o f assets/liabilities.G iven this divide of assets/liabilities one can m easu re the com ponen ts in the foundation equation:cash earnings+net accrual=com prehensive earnings.The paper then proceeds to discusshow the netaccrual relates to grow th in a f rm’soperating activities and the extent to which it can be in formative or m isleading. This topic in turn integrates with the issue o f a f rm’s quality o f earnings and the ro le of accounting conservatism.Among the remaining topics,the paper d iscusses how one concep tualizes d iagnostics to assess w hether o r not a period’s accrual is likely to be biased upwards or downwards.It gives rise to a consideration of how one constructs accruals thatmay bemore in formative than GAAP accruals and the ro le o f value-relevance studies to assess the information content of accrual constructs.The paper ends w ith a list of suggestions how future research may bemodif ed in light of the discussions in this paper.

©2014 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf o f China Journalo f Accounting Research.Founded by Sun Yat-sen University and City University o f Hong Kong.

1Asan illustration of im plementation“details”,inmany studiesearnings serveasan ingredient tomeasureeither cash fowsor accruals. The researchermust then decide on the earnings number to use:which,if any,special item s should be excluded?.Introduction

Research on“accruals”has grown signif cantly over the past 15 years,themostwell-known papers being due to Jones(1991)and Sloan(1996).While thisextensive literature dealsw ith a variety o f questions,mosto f thepapers in oneway or another consider thestatisticalp ropertiesof accruals–or thepropertieso f cash fows vs.earnings.These f ow variab les p romp t the issue o f how one converts f nancial data into a period’s cash fowsor accruals.A review o f the literature bearsout that there are numerousapp roaches to themeasurement of accruals.Some of thesedepend on changes in balancesheetaccounts;other studiesstart from statementso f cash f ows and ad just key numbers using information extracted from incom e statements.Specif c details in individual studies can also vary,so readersm ay be left w ith an uneasy feeling that research execu tions allow fo r too m any degrees o f freedom.1Asan illustration of im plementation“details”,inmany studiesearnings serveasan ingredient tomeasureeither cash fowsor accruals. The researchermust then decide on the earnings number to use:which,if any,special item s should be excluded?One can safely assert that the literatu re of ers no“standard ized”way o f putting the 3 com ponen ts–cash fow s,earnings and accruals–together.Nevertheless,the various efo rts atmeasuring accrualswould seem to be based on a common understanding as to the nature of accruals;when studies discuss themeasurement of accruals they do move(broad ly speaking)in a sim ilar direction.2Th is paper does not compile extensive references to the large literatu re,emp irical and concep tual,that dealsw ith accruals and linked topics.Ishould further underscore that there are really few new ideas in this paperand yet Ihave not tried to attributevarious insights to originatorsas iscommonly done.Itwould havebeen too dif cultand thorny to develop the relevantcitations.The topicscovered–like the general idea o f an accrual–have long historiesw ith non-standardized term inology and an enormousnumber of applications in research. To get started on navigating the literature,the follow ing papers should prove usefu l.Jones(1991)and Sloan(1996)have been m entioned in themain text’s f rst paragraph and thus they have a signif cant statusas“classics”.W ith respect to textbooks,Penman(2009)provides an introductory discussion of thequality o fearnings issue asit relates to accruals.Seealso the textbook by Easton etal.(2009).Fora very broad perspective on the quality of earnings topic,see Dechow et al.(2009).M elumad and N issim(2009)discuss quality o f earnings specif cs for num erous line itemssuch as theaccounting for pensions,inventories,deferred revenues,etc.Quality of earningsevaluationsas it relates to changes in balance sheet conservatism can be found in Penman and Zhang(2002).Oh lson and A ier(2009)discusswhat they refer to asmodifed cash accounting(“M CA”)earnings–ameasure of cash earnings–asopposed to accrual earnings and they exp lain how M CA f ts into the quality of earnings literature.The paper particularizes the cash assets/liabilities vs.other assets/liabilities dichotomy and it discusses the full range of judgm ent issues,including the use of footnote disclosures to measure cash earnings.Emp irical work related to GAAP accruals–their reversal properties aswellas trading strategy opportunities–A llen et al.(2009)summarizeswhat onemay refer to as themost recent state-of-the-art of accrual research when it comes to em piricalwork.Richardson et al.(2009)review the literature on accruals and anomalies,and it lists just about all references that one can reasonably hope for.

M issing in allof thisempirical research isan analysiso f the concept o r construct of an accrualand its imp lications.3To be sure,the concept of an accrualas em p loyed in this paper always refers to a(period’s)fow.The reason fo r noting this obvious convention here is that an o ften cited paper by D echow et al.(2002)suggests that they have m odeled accruals,which in my m ind is unfounded insofar that they are actually dealingw ith stock variables.Specif cally,inm y reading of the paper,ithas the f avor of amodel of“errors”in balance sheet accounts–which are stocks and not fows.The errors pick up biases(upwards or downwards)as to the expected cash that w ill be realized at the end of the period.In m y interpretation,therefo re,rather than capturing accruals them odel in question develops the consequences of fair m arket valuationswhen these can refect an upward or downward bias.Such absencemakes it hard to assesswhether there are otherworkable(perhapsbetter)alternatives to the accrualmeasurements found in specif c studies.These hypothetical alternatives could lead to diferent (or less robust)empirical f ndings,suggesting theneed for an accrual concep t.In thebackground lurksamore fundamental issue,however.Only after a construct is in p lace can oneexam ine the circumstancesunderwhich accruals have a p ractical role in valuation because they benef cially complement cash earnings.This sets the stage fo r an analysis o f when accruals tend to m isin form rather than info rm investo rs.

This paper develops and evaluates an accrual construct which I view as particu larly useful.It is no t new. Textbooks,like Penman(2009),refer to it as“change in net operating assets.”M uch o fwhat is discussed in this regard reaf rmswhatmany readers have seen elsewhere.Yet in key respects the analysis here diverges from what the literature puts forward.This paper places the emphasis on ideas and how theses forge links as opposed to a critical evaluation o f thework that hasbeen done(and how it perhaps cou ld be imp roved). It applies to any accounting that satisf es the basic stocks-f ows reconciliation built into accounting.Thus the paper tries to deal with questions of broad interest which hopefu lly should supply a concep tual foundation for those individuals who try to fam iliarize themselvesw ith the literature,or who aspire to a better sense of what onemay call the“big picture.”Follow ing that,the paper discusses empirical questions relatedto properties of accruals,includ ing the question of how one can evaluate whether accruals are in form ative or not.

Because this paper dealsw ith topicsand themes thatare by no meansnovel,much w illbe fam iliar to individualsversed in the literature.That said,how thevarious ideasconnectwith each othermay be lessso.As the linksoften involvesubtleties,thepaper envisions thatoneobtainsamuch better understanding o f sub jectm atter if one proceeds step by step without distracting discussionso f empirical research papersand their f ndings. In sum,the f ow and interdependence of ideasw ill be central.

To give the reader a sense of topics covered,the follow ing supp lies a list that the paper develops in some detail:

·The construct o f an accrual depends so lely on(consecu tive)balance sheets and the classif cation o f assets/liabilities into approxim ate cash assets/liabilities as d istinguished from o ther assets/liabilities. The latter classo f assets/liabilitiescan be thoughto f as those related to operationsasopposed to f nancial activities.

·Concep tually and practically,to identify an accrual via cash f ows statements combined w ith earnings con fuses issues.Nor does it generally help to identify non-cash expenses such as dep reciation if the focus is on a period’s total accruals.

·In terms o f econom ics,an accrual relates to the grow th in operating activities alone.Under ideal circumstances themeasurement o f grow th in operating activities and the accrual hasa one-to-one correspondence.Financial activities do not in fuence the accrualmeasurement though these activities do o f cou rse reconcile w ith operating activities.

·The quality of earnings dependence on accruals is essen tially independen t of balance sheet conservatism;it is the change in the degree of conservatism that counts.4In the context of this paper,“quality o f earnings”pertains to the idea that the cu rrent(net)accrual infuences the fo recasting of earn ings in an upward or downward direction.If upwards(downwards)then the current earnings are of high(low)quality.Sim ilarly,the in formation content of accrualsshou ld notbe conceptualized in termsof theextent to which operating assets/liabilitiesdeviate from their fairmarket values.

·An informative accrualmeasures the growth in operating activities w ithout a subsequent reversal:a serial correlation in total accruals is p rim a facie evidence o f“bad”accounting.

·Dealingw ith the quality o f earnings issue per GAAP reduces to attemp ts to come up w ithmeasureso f grow th in operating activities thataremore informative than theaccruals imp lied by GAAP.Such competing measure of grow th in operating activities should facilitate the forecasting of future(operating) GAAP earnings.The grow th of sales is poten tially useful insofar that it generally ough t to relate to grow th in operating activities.As a practicalm atter,it leads to the hypothesis that the quality of earnings is low when the grow th in sales is less than the grow th in net operating assets.

·Traditional value relevance(cross-sectional)regressions–stock market returns on same-period accounting data–can assess the information content o f accruals by putting it on the RHS w ith cash earnings.The methodology also perm its a comparison of GAAP accruals to what one may hypothesize to be more informative measures o f accruals.A particu larly interesting question relates to the issue if one can construct an accrual that loads the same in the regression as cash earnings,in which case the two numbers aggregate w ithout loss of in formation(in other words, on the regression’s RHS one can add cash earnings and the accrual w ithout signif cantly reducing the R2).

2.Basics:Accruals and fnancial statements

W ithout referring to any particu lar accounting p rinciples,accounting introducesaccrualsbecause transactionsmay,ormay not,have a cash component:

Cash Earnings+Accrual=Earnings.

This relation is def nitional and thus not subject to challenge(the accrual,to be sure,is the total for the period.)5One can ask whether cash earnings and cash fow s are two d iferent labels for the sam e thing.The literature lacks a standardized terminology if and how one distinguishes between the two terms.M ost papers(if notall)use the term ino logy“cash fows”and make no reference to cash earnings,explicitly or im plicitly.In doing so it seem s thatone should notgenerally equate cash f ows to cash earnings. Such ism y judgm en t at least.It ismostly based on the fact that autho rs seem to have in m ind that the cash fow s in question pertain to current cash fows,w ith no ad justment for capital expenditures.Jones’s paper illustrates that;the average accrual is negative because it excludes theefect due to theaverage increase in PPE.Hence thispaper doesnotembed a concep tof cash earnings.Other papersdealsw ith accrualsmuch the same,though thereareexcep tionssuch assomeof themore recent Sloan papers.It ism y opinion that the cash earnings construct–w ith an em phasis on earnings–should serve as a starting point in any analysis of accruals,em piricalo r theo retical.Thus I maintain th is perspective th roughout,and Ido no t discrim inate between cash earnings and cash fow s.If the RHS is determ ined by GAAP(o f any jurisdiction)and cash earningsare determ ined by some other accounting regime consistentwith the term cash earnings,then the accrual is imp lied.M ore generally, any one o f the three quan tities can be in ferred from the rem aining two,o f cou rse.In the literatu re one f nds a m ixture of app roaches though it does seem as if earnings(before or after som e special item s)are always taken as a given.But this observation about practice in em pirical research should not be con fused w ith som e notion that them easurement o f accruals or cash earnings presupposes an earnings number.Such thinking is unnecessarily rigid.

Asa practicalmatter,onem ightwellmeasureaccrualearningssuch that thenumber derives from two independently established components,cash earningsand an accrual.One can thereby think of accrualsashaving been measured independently o f some existing balance sheets or an integrated set of fnancial statements.To consider the measurement of accruals w ithout reference to earnings,balance sheets or cash fows is by no means fancifu l.This app roach becomes themodus operandi in the discussion of the topic“quality o f earnings”as it relates to accruals.This paper revisits this idea in the discussion of this topic later.Before getting to that poin t the focusw illbe on caseswhen specif c assets/liabilitiesand their carrying valuesare in p lace,i.e., what onem igh t call“regu lar accoun ting.”

In regu lar accounting,start-and end-of-period balance sheetsunderpin earningsm easurements.The claim app liesno less to themeasurementof cash earnings than to(accrual)earningssinceboth cases require that the fows reconcilewith thebeginning–ending stocks.Cash earningsand regular accrual earningsaccordingly differ on ly in the listing o f assets/liabilities(and their carrying values)that support the two earningsmeasurements.W hile the specif cs of how one identif es the two sets o f assets/liabilities raises its own issues,which will be discussed later,herewe note that to concep tualize cash earnings independently of supporting balance sheets removes us from regular accounting.

Suppose next that,(i)the accounting satisfes clean surp lus for both conceptso f earnings,and(ii)the dividendsand capital contribu tions are o f a cash variety,i.e.,the two accoun ting regim es treat these transactions the sam e.It fo llow s that the accrualequals the d if erence between the two regim e’s netwo rth changes(ending m inus beginning balances).

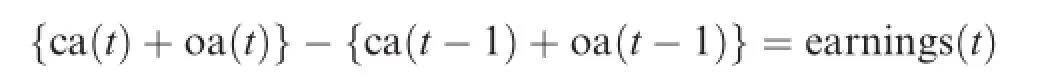

The last sentence is awkward in its claim that the accrual derives from diferences after having looked at changes over a period.Elementary algebra helps to communicate the statement.In the interest of simp licity, assume zero dividends and capital contributions.First note that one in fers earnings from the clean surp lus relation,i.e.,the increase in networth(or book value).Second,suppose that all asset/liabilitiesmust be classif ed into one or the other out o f two kinds:

ca=cash assets and the app roximate equivalent o f cash,positives net o f negatives.

oa=other assets/liabilities,net.

Then

The notation m eans that one identifes cash earnings as

ca(t)-ca(t-1)=cash earnings(t)

One trivially in fers that

oa(t)-oa(t-1)=accrual(t)

In o ther words,the d if erence in non-cash assets(net of non-cash liabilities)identif es the accrual.As the last expression show s,it is in ferred from assets/liabilitieso ther than cash(and itsapproxim ate equivalen ts,positive or negative).

The above developm ent disregards dividends and capital contributions.But such transactions do not change theanalysisas long asboth accounting schem esaccount for these thesame.Onemodif es thedefnition o f earnings by replacing ca(t)w ith ca(t)+net dividend(t),keeping ca(t-1),oa(t)and oa(t-1)the same. (Thereare no apparent reasonswhy the accounting for dividends/capitalcontributions should notbe thesame for the two earningsmeasurements.)

A delicate pointmust be noted.Because the arrangement embeds clean surp lus accounting,each of the earningsmeasurementsmust be comp rehensive.Any alternative app roach would have to re-defne the three ingredien ts in the foundation equation.6W ith the notab le exception of H ribar and Collins(2002),the literature on accruals does not pay attention to this point.It leads to a slippery slope:the defnition o f earnings can vary w idely across studies in their treatmentso f special items.Fo r exam p le,one can try to identify how“o ther com prehensive gains/losses”im pact on the 3 elem ents in the foundation equation.It should be doab le.(That said,the literature does not p rovide clear guidance as to whether this is the righ t way to proceed o r no t.)

Though the relations imposediscip line on how diverse pieces f t together,nothing hasbeen said aboutwhat characteristics should identify a cash asset/liability asopposed to“other”assets/liabilities.Thisp ractical,and essential,topic is dealtw ith later.But there is o f course substantial agreement on the difering nature of the two classes of assets/liabilities.Consider,for example,a balance sheet comprising the follow ing prototype assets/liabilities:(i)cash,(ii)liquid marketable securities,(iii)inventories,(iv)net p roperty,p lant and equipm ent,(v)accrued expenses,(vi)accounts payab le,and(vii)bank loans.M ost peop lewou ld then surely agree that(i),(ii)and(vii)fall into the category o f ca(t).The liability(vi)may seem less than obvious,but it,too, shou ld bepartof ca(t)if it representsan outstanding liability as long asa defniteamounto f cashmustbepaid to extinguish the deb t(in other wo rds,its econom ic essence does no t difer from a bank loan).The rem aining assets/liabilities fall in to the oa(t)category by necessity.7To be sure,em piricalstudies that dealw ith accruals have often concep tualizedm easured accruals in ways that difer from theapproach suggested in this paper.,8Textbooks,like Penman(2009)and many papers refer to NOA as representing“netoperating assets”.Does it correspond to oa(t)?The answer isa qualifed yes.Therearediferences insofar that NOA tend to pertain to operations rather broadly,and thusit typically includes accounts receivable and payab le p lus even som e portion of cash necessary to operate the business.I tend to think of oa(t)mo re narrow ly like in Oh lson and Aier(2009).Now ca(t)includes(oa(t)excludes)all assets/liabilities that one can reasonably add/deduct from cash w ithout losing information.Thus high quality accounts receivables and accounts payab le are not treated as being accounted for via accruals.(The reader has to use his/her own judgmentwhatmakes themost sense.)A tany rate,as Richardson etal.(2009)makes clear, m any recent papers on accrualsdefne the net accrual in terms of the change in NOA which of course in its essence does not difer from the accrual construct considered in this paper.

The above developm ent,sim p le as it is,lays bare that to add back dep reciation and other so-called non-cash items to earnings are,at best,an around-aboutway when one construes cash earnings.The point rein forces that the concept o f an accrual rests on a consistent classif cation o f assets/liabilities in consecutive balance sheets,not on evaluating the line items in an income statement and fnding their(non-)cash components.M oreover,tomeasure a GAAP accrual,there are no compelling reasonswhy onemust turn to a statem ent o f cash fows per GAAP.The sim ple balance sheet framework shows that an accrual construct hingesonly on the idea that assets/liabilities can be sp lit into two m utually exclusive yet exhaustive catego ries.To advocate otherw ise at the very least demands some justif cation.9Inm uch of the literature one fnds that papersmake no attem pt atm easuring the period’s accrual in its totality.Instead,the idea is to focuson something referred to as the“current accrual”.Thus onemay consider the casewhen oa is split into two categories,{1,2}.Let oa(1,t)+oa(2,t)=oa(t),and sim ilarly defne accr(1,t)+accr(2,t)=accr(t).One can then w rite ce(t)+accr(2,t)=earn(t)-accr(1,t) where one can interpret the accrual term on the RHSas the currentaccrual.W ith some slightabuseo f languageone can then refer to the RHS as a calcu lation of“cash fow s”.Roughly,it can be though t of as corresponding to“cash provided from current operations”before depreciation and am ortization.Thatsaid,oneneeds to keep inm ind that it is im p licit that thereareother accruals thatm ust be accounted for to derive cash earnings.(Just as one needs to keep in mind that itmakes a diference if one considers comprehensive earnings as opposed to some othermeasure of earnings.)

The above assets/liabilities examp le illustrates what most accountants take for granted,namely that measurements related to cash assets/liabilities are less“ambiguous”than the remaining ones(oa).Cash assets/liabilities(ca)are relatively unambiguous insofar that their carrying values for(most)p ractical purposes approximate their market values.One can take this observation one step further and argue that cash assets/liabilities by def nition are those assets and liabilities that generally match their market values. In contrast,all assets/liabilities falling into the oa(t)category have ambiguous carrying values:the accounting p rincip les and their applications tru ly come into play(e.g.,depreciation schedu les,the equity m ethod for unconso lidated subsidiaries,restructu ring charges,pension liabilities,inven tory accoun ting). There is no requirem en t that the carrying values o f these other assets approxim ate their fair values o r m arket values.In fact,the assets/liabilities com p rising oa(t)would be no easier to deal w ith if one tried market(or fair)valuations because value-creating assets/liabilities are intrinsically illiquid.(A t a m inim um, one has to con front the relevance and p ractical meaning o f net realizab le value when the market is indistinct.)110An elabo ration o f theword“am biguity”helps to appreciate the operating vs.fnancialactivities distinction.Am biguous valuation of operating assetsm eans that they interconnect and have a perceived value which is entirely idiosyncratic to a f rm and depends on its strategic plan.These contextualusevaluesare inherently very subjective.It leads to the im perative of transactions-contingentGAAP rules to generate carrying values for the balance sheet.Thus the income statement dependson the accrual–the change in the carrying values–though it isunderstood that thebook values of operating assets do not in any real sensehavemuch of a connection w ith themarketvalues ofoperating assets,separately o r in their totality.Cash assetsand liabilities,in contrast,can be valued w ith less(or ideally no)am biguity in that their use value and they are nowherenear as contextualand dependenton a f rm’s strategy.Thus the use of theword“ambiguity”is not to be thought o f as“arbitrary”,“non-nonsensical”or“best disregarded”or anything like it,but rather that contextual use values becom e exceed ingly dif cult to p in down from a balance sheet perspective.But that of course does no t preclude that non-fair value rules can be quite useful in themeasu rem ent of earnings.

While the idea o f sp litting book value into ca(t)and oa(t)is predicated only on a basic understanding o f accounting,implementations of the framework put the onus on judgments.To illustrate,consider accounts receivab le.If these are of high quality–on ly an immaterial allowance for bad debts is needed–then they f tneatly into the ca(t)category.Under the circum stance they are in their econom ic essence sim ilar tomarketable securities;both can be so ld w ith some ease for predictab le amounts.A material balance in the allowance account relative to accounts receivable,in contrast,suggests that the net receivable is likely to be am biguous;it natu rally leads to an oa(t)classif cation.Bu t the subjective natu re of p ick ing the appropriate cu t-of poin t related to the percentage o f allowance balance is unavoidable.Sim ilar sub jective judgments as to the ca(t) vs.oa(t)classif cation must be faced in case o f assets such as fnance receivab les and more or less illiquid investments(like partnerships).Liabilities are no less problematic when it relates to cash estimates,such as obligationsoutstanding to em ployeesand supp liers.An amount that seems relatively predictable tilts the classif cation in favor of a cash liability,o f course.

3.The economics of accruals

The relations and observations so far deal so lely w ith def nitions,classif cations and the structure o f accounting.In no substantiveway havewe tack led what onemay call“the information content”of accrualsin com bination w ith that o f cash earnings.In teresting questions arise.W hat inform ational purpose do accounting accruals serve?W hy recognize assets/liabilities with inherently ambiguous carrying values?Can onegenerally expectaccruals to add to cash earningsw ithout losso f in formation?Or are theymore likeapples and oranges?

Traditional accounting concep ts speak to these kinds o f questions by referring to two slightly diferent app roaches:either one focuses on the end-o f-period balance sheet or on the period’s incomemeasurem ent. Both app roaches rely on the idea that accrual accounting countermands the def ciencies inherent in cash accountingwhen there are costly strategic activities that serve as the foundation for potentially creating value in subsequent periods.

From a balance sheet perspective,any reasonable concep t o f asset(liability)suggests that the lack o f am biguity of an asset’s carrying value cannot be a requirem en t to recognize an asset.To invest in operations,f rm s m ust incu r expenditures that are in trinsically dif cu lt to value since their ef cacy depends on the business strategy.But at least some o f these expenditures o fer expected future benef ts in terms o f subsequent sales, however ambiguousand hard to evaluate these connectionsm ay be.Such future benef tsought not to be dism issed and treated as a period expense if one looks for a more comprehensive picture of a f rm’s econom ic condition.In other words,assigning zero value to expenditures that generally enhance subsequent sales contradicts basic econom ics.

If one focuseson earningsmeasurement directly,then cash earningsalonem islead asameasure o f perform ancewhen the company incurs expenditures that benef t the future.An adjustment in the form of an(net) accrual is now necessary insofar the f rm has increased the size o f its operations.A fter all,a f rm cannot expand operationsw ithout d isbursing cash o r itsapproxim ate equivalent thereby reducing cash earnings;cash earnings decrease as the f rm invests in the fu tu re in a one-to-one fashion if the p resum p tion is the benchm ark o f zero NPV.In thisway an accrual can be interpreted ashaving a one-to-one correspondencew ith grow th. M ore precisely,the oa(t)’s percentage increase equals accrual(t)/oa(t-1);it serves as ameasure of a f rm’s growth in operating activities.The sign of the accrual,accordingly,determines if a f rm expands or reduces its operating activities.

There is a subtlety involved that needs to be underscored.W hy does them easurement of grow th center so lely on oa(t)as opposed to the total book value,oa(t)+c(t)?The answer requires an appreciation o f traditional f nancep receptsw ith itsdemarcation of operating vs.f nancialactivities.W ithin this framework other assets,oa(t),stands for operating assets.These are the assets that pertain to ex ante value creation–an inherently subjective and uncertain econom ic activity when it com es to assessing the likelihood of fu tu re success–thereby causing the am biguity in the valuation o f such assets.In contrast,the assum p tion is that changes in cash assets/liabilities are ob jectively neu tral when it com es to forward looking value creation–zero NPV is imp lied–which is p recisely why they are comparatively easy to account for.Unsurprisingly,carrying values for the cash and cash equivalent assets are close to their fair(market)values.In the spirit of M odiglianiand M iller,one naturally def nes the cash assets/liabilitiesas the fnancial assets/liabilitiesbecause of their value creation neutrality.Hence the cash(equivalent)assets/liabilities,and their changes,cannot tellusanything about the grow th of the value creating activities.Any change in ca(t)ad justed for the net dividend–cash earnings–is o f course inf uenced by operating activities,but that aspect does not bear on the change in the operating activities per se.11One can reasonab ly claim that this paper stretches language-usage insofar that it equates the accounting fo r operating activities w ith accruals and fnancialactivitiesw ith cash-equivalence.Such a one-to-one correspondence is at variancew ith text-books in som e respects. But these exceptions arem inor.Thus here the understanding is that the accounting for,say,the amortization of a discount related to a bond is not an accrual.It is also understood that there is no cash necessary for operating purposes.In the grand scheme of problem s d iscussed in this paper we believe this is reasonable.That said,one can certainly entertain refnem ents o f the framework laid ou t in this paper.

The above discussion hints at the possibility that the accrual’sm agnitude should bear on the subsequent expected cash earnings(or cash f ow s,to fo llow the literatu re).Is such the case?On heuristic grounds the answerwould seem to be“yes.”A fter all,the accrual cap tures a net increm en tal investm en t,and one can think o f this investm en t as increasing the expected futu re sales.W ith an unchanged m argin,it follow s indeed that one should expect improved cash earnings.Thisargum ent perm its tightening;one can develop p recisely howan accrual forecasts future cash earnings.This can be done w ithout m aking any reference to futu re sales (though this helps to motivate the conclusion).12The literatu re suggests that a valid accrual should perform as a leading indicato r of(o r forecast of)subsequent cash earnings(or cash fow s).The idea seem s reasonable enough,though it’s f rm ing up is perhaps less so.Anym odeling of how period t’saccruals lead to t+1 cash earningsmust confront that the future cash earnings interactw ith the same-period expected accrual.The point cannot be fnessed. Future cash earnings depend directly on future grow th in investments in operating activities;in turn the latter investment determ ines the future accrual.Itgives rise to the question:asamatter of concept,how does the currentaccrual relate to future cash earningswhen one allow s fo r grow th in the accrual?To answer th is question,we need(i)an assumption on them eaning of a valid(or“properlymeasured”, perfect)accrual,and(ii)an assumption on thesignif canceo f cash earnings in valuation.As to the latter,(ii),assume that themarketvalue of operating assets is determ ined by the present value of cash earnings(to be sure,themarket value generally dif ers from oa(t)).To keep themodeling simple,assume that the cash earningsare paid out in dividends.W ith respect to the f rstassum ption,(i),assume thata perfect accrual satisf es V(t)=[(1+r)/r][ce(t)+accr(t)]-ce(t)and where thus,per(ii),V(t)=PV o f expected cash earnings=∑τ≥1(1+r)-τEt[~ce(t+τ)].(There is no need to specify the date t conditional information.)W ith these two assum ptions in place,nomore and no less,routine derivations lead to the dynam ic Et[(■accr(t+1)+Δ~ce(t+1)]=(1+r)(accr(t))The expression shows that the currentaccrual forecasts the change in cash fows plusan ad justment for the future expected accrual.In the special casewhen the expected accrual in the next period is zero(a no grow th setting),then,and only then,does the curren t accrual forecast the change in the expected change in cash earn ings(def ated by(1+r)).M o re generally,denoting the grow th rate in operations by g(which can be in form ation dependent so we cou ld actually w rite g(t)),one obtains the answer to the question posed above: Et[Δ~ce(t+1)]=(r-g)(accr(t))Note that at date t it may be the case that r=g.Now the RHS equals zero so that current cash earningsprovide an unbiased estim ateof next-period’s cash earnings,regard less of the curren taccrual.A sim ilar forecast also app lies if the current accrual iszero,i.e.,there has been no new net investm ent in operating activities.The concepto f an accrual,as def ned here,m eans the(net)accrual is equivalent to the(net)new investment in operating activities.To underscore this point,consider what explains the expected change in operating earnings:If ox(t+1)denotes expected operating earnings(cash earnings plus accrual),then one readily show s that ox(t+1)-ox(t)=r.accr(t).This relation is of course p recisely what one should expect.One obtains this result w ithout restrictions on the time-series behavio r of accr(t),the poin t being that themodel em beds no such restrictions.

Readers fam iliar w ith the concep t of“Free Cash Flows”,FCF,may ask how ameasure o f cash earnings relates to FCF.To address this issue,two issuesmustbedealtwith.First,FCF often classifesA/R and A/Pas operating rather than fnancial.But this seems rather arbitrary,so one can assume that all qualifying cash assets/liabilities relevant for cash earnings coincidew ith fnancial assets/liabilities.Second,with this requirement in place FCF sim ply equals cash earningsad justed for income/expenses related to fnancialactivities.In particular,if one con fnes such expenses to interest itemsw ith a common interest rate,then FCF equals residual cash earnings.

4.Linking growth to accruals:A model

This section p resents a stylized model o f“p roper”accruals.It formalizes that grow th and accruals constitutes two sides of the same coin.Pointsmade in the previous section shou ld thereby be rein forced.

Let ce(t)denotes the current cash earnings(f ows)for the period t and assume that these are paid out in dividends(to keep matters simp le).Students o f fnance then learn that under perpetual,geometric expected grow th the value o f the f rm fo llows from thewell-known formula

V(t)=ce(t)(1+g)/(r-g)

where

g=grow th rate(e.g.,0.04%or 4%))

r=discount factor(e.g.,0.1%or 10%)

ce(t)=ca(t)-ca(t-1)+net dividend(t)=cash earnings(t)

Accountants dif er from f nance theorists in that they focuson earnings,ce(t)+accr(t),as the key input in the valuation as opposed to future cash earnings.Under idealized circum stances they have com p lete confdence in the accrual–it com esw ith no error whatsoever–so the earnings are also error free.The accountan t can therefore refer to earnings capitalization to value the futu re cash earnings:

V(t)=[(1+r)/r][ce(t)+accr(t)]-ce(t)This fo rm u la corresponds to the one used to value earnings from a savings account:earnings capitalized by (1+r)/r determ ine the cum-dividend value.

Can the accountant and fnance student both be right?Yes:equivalence ho lds if and on ly if the accrual equals

accr(t)=g×V(t)/(1+g)

In otherwords,the accrualm ust emulate the grow th in the expected cash earnings.(Routine algebra p roves the equivalence).And no te that as an app roxim ation one can leave ou t(1+g)so that accr(t)is approxim ated by g×V(t).(The inverse o f(1+g)is app lied to V(t)to estim ate the start-of-period value o f V,V(t-1).)The expression show s that the greater the grow th,the greater the accrual and conversely.

Simple as the abovemodel is,it doesachieve the insight that,under idealized conditions,ce(t)and accr(t) add w ithout lossof in form ation.Know ing earningssuf ces to infer the cum-dividend value of the f rm,yetone cannot in fer theaccrualor cash earnings.(In general,the dividend need not equal the cash fow,in which case one cannot infer the two components of earnings.)

Asan obvious imp lication of themodel,cash accountingmeasures earningswithout error if and only if the f rm is in a steady state,g=0.Thusone can think of a steady state asa condition when there isno need for an accrual.These observations build in the so-called cancelling error property:zero grow th corresponds to no change in the oa(t)and hence themagnitude o f oa(t)=oa(t-1)itself is irrelevantwhen onemeasures earnings.Aswe w ill see in the fo llow ing sections,the no grow th benchm ark can usefu lly guide p ractical f nancial statem ent analysis.

5.Accruals and the quality of earnings

While the abovemodelingmay help usapp reciate the econom icsof accruals,the realworld isof course far m essier.There isno such thing as a true and observable accrual,but rather a sense that an accrual can m isin form aswell as in form depending upon circumstances.Practical fnancial statementanalysishas long recognized the problems inherent in GAAP balance sheets and the accruals embedded in income statements. Because the operating asset’s carrying values are intrinsically ambiguous,there is undeniably a sense that GAAP accoun ting can result in d istortions and m isinfo rm ation.The reasons fo r poten tialm isinfo rm ation are diverse.They include the sheer com p lexity o f accounting ru les,and perhaps even m alevo len tm anagem en t in tentions.In the latter case“earningsm anagem en t”tends to be the standard term ino logy.Thus f nancialanalysts become aware that“earningsmanagement”can lead to m isleading earnings through the accruals.In research one often f nds references to“discretionary”accruals,which is o f course what Jones’smodel aims at.But thisbehavioralaspect should not be exaggerated.No less important are GAAP-consistent non-recurring charges that can have a very material efect on current and subsequent accruals,especially when these charges involveno cash.(A w rite-of reduces the currentaccrualand increasessubsequent accruals,of course.) Because o f potentially inherent def ciencies in GAAP,m isleading accruals should not be ru led out even in the case of honestmanagers.The point deserves pondering insofar thatmuch of the literature puts the onus on m anagerswhen accruals have undesirab le p roperties.

Early on the paper em phasized that accoun ting relies on accruals because at least som e assets/liabilities do not adequately connect w ith(approxim ate)cash values or,as accoun tan ts tend to put it,fair values.This observation m ay suggest that the p rob lem s w ith accruals can be traced to the lack of fair valuations fo r all assets/liabilities.Such a claim,however,is at bestm isleading:deviations from this p resumed ideal shou ld notbe thoughtof as thesourceof erroneousaccrualmeasurements.Such reasoning putsuson thew rong track because it suggests that“good”accounting is founded on fairmarket valuation.Traditionalaccounting rejects this app roach because o f itsemphasison incomemeasurement;it buildson historical cost accounting including its extensions that stipulate realization princip les for revenues and pro f ts.

Nor does the degree of(or lack o f)balance sheet conservatism act as amaterial culpritwhen an accrual m isleads.The substantive issue revolvesaround the extent to which there isa change(date t compared to date t-1)in the degree o f conservatism.Increasing the degree of conservatism im proves the quality of earnings and conversely when it is decreased.

Financial statem en t analysis teaches that overestim ateso f earnings tend to be followed by understatem en ts and conversely.Thisobservation in essence cap tures accrual reversals.It can also be thought of as being no diferent from overstatem ents and subsequent understatements o f reported grow th in net operating assets, which in turn refects the“quality of earnings.”Thus it becomes clear that,(i)understanding the characteristics of the period’s accrual is necessary and arguably suf cient to understand a f rm’s operating income,and (ii)one needs to focuson changes in the degree o f conservatism not the degree of conservatism itself,a point developed below.And asone thinksabout the quality o f earningsonemust always keep inm ind that the relevant construct–the validity o f the grow th in oa(t)–disregards the cash&(approximate)cash equivalent assets/liabilities.This aspect appeals because such easy-to-value assets/liabilities cannot be a source o fm isleading accoun ting(assum ing no aud iting type p rob lem s).

O f course,the“co rrect”oa(t)are never observable,and m ore im portantly,nor is the“correct”oa(t)-oa(t-1)or grow th in oa(t)observable.It still helps to conceptualize the ideas o f quality o f earnings and reversals in terms of the correct oa(t).Themotivating algebra runs as fo llows.

Suppose the oa(t)are correct and that these grow at a steady rate,g>0.Consider next,two periods that end at dates t+1 and t,respectively.Now suppose the reported oa(t)exceeds the correctoa(t).It fo llows trivially that the observed period t+1 grow th is less than g,whereas theobserved period t grow th is larger than g. In this sense the low quality of earningsbuilds in a reversal in accruals.Asan interesting special case,noted earlier,if the true g equals0,then any accrualactsas“purenoise”and negativeaccrualsare followed by positive ones and conversely.Thus one can safely say that the accruals shou ld be regarded as unin form ative.A steady state setting thereby serves as an easy to app reciate case when accruals are both non-in formative and negatively serially correlated.

Balance sheet conservatism does not by itself bring onm easurem ent biases,provided that the extent o f conservatism has been consistently applied across dates and the focus is on grow th itself.To demonstrate this, suppose one scales the oa(t)’sw ith a constant,k>0,which serves as index of lack of conservatism.In other words,w rite k·oa(t)so that theaccounting ismore conservative in relative termsasonedecreases k.It is readily seen that the grow th rate in operating assets remains the sam e for all k,that is[k·oa(t+1)-k·oa(t)]/ k·oa(t)doesnot depend on k.M oregenerally,without resorting to an index scalar,the quality o f(operating) earnings for period t+1 is poor if and only if the degree of conservatism has decreased,date t+1 compared to date t.Thisanalysis changes som ewhat if one shifts the attention from a grow th perspective to onewhich scales the diference oa(t+1)-oa(t)by a constant.Now therew ill be an ef ect:the accrual decreasesas the degree of conservatism increases.However,w ithin practicalbounds this efect is relatively sm all(and the sign rem ains in tact).Thus the substantive quality o f earnings issue reduces to the extent there hasbeen a change in the degree o f conservatism from one period to the next.

6.How to conceptualize accrual biases as a practicalmatter

The notion o f an under-or overstated accrual suggests,at least implicitly,that there is something like an accu rate,or at leastm ore accu rate,accrual.The claim is aw kward since the degree o f accuracy in accruals is never observab le,no m atter how m uch tim e has passed.Shallwe then overlook what good/bad accoun ting is allabout and accept that one has to livew ith the accrualsas p rovided by GAAP?The answer to this question, I think,must be a resounding“no”:p ractical f nancial statement analysis w ill always be concerned w ith accrual biases because over time overstated accruals reverse.It leads to the saying“the(operating)earnings reported for the current period can be a poor indicator ofwhatw ill be reported in the future due to the current/past accruals.”

So,how do we assess the degree of bias,or the potential for future reversals,in any GAAP accrual?To answer this question one tries to make themost of the accrual and grow th connection.

Two separate steps show theway to an estimate o f a competing accrual.First,one estimates the current value o f the f rm’s net operating assets,which thus second guesses the actual accounting oa(t).Let est_oa(t) denote this estim ate.Second,one estim ates the cu rrent grow th independently of the cu rrent grow th in oa(t). Independence isessential since the presum ption is that the actualaccrual,oa(t)-oa(t-1),m ay dif er from its“true”m easure.LetΓdeno te an independen tly estim ated grow th in operations.The product of the two term s then yields an estimate o f the“app rop riate”accrual,which competes w ith the one implied by GAAP.Putm ore blun tly,this two-step p rocedu re is intended to second guess the GAAP accrual under them ain tained hypothesis that this accrual cou ld bem isleading:the sign and dif erence between the estimated accrual vs. the GAAP accrual establishes the accrual bias or“the quality o f earnings”conclusion.

As to the f rst step,theest_oa(t)term,itmay seem natural to estimate itusing a f rm’smarket capitalization adjusted for ca(net fnancial position).But thisapp roach has the drawback that it essentially p resumes that the accounting isunbiased asopposed to conservative(from a balancesheet perspective).Under such circumstances the estimated accrualw illnotbedirectly comparable to a GAAP-based accrualsince GAAPembraces balance sheet conservatism.In addition,one can also argue against thismarket valuemethod because it p resumes rational pricing(an“ef cient”stock market);it puts the cart in front o f the horse since the f nancial analysis tries to assess whether the p rice d if ers from the f rm’s in trinsic value.These ob jections suggest that itm akesm ore sense to use accounting based estim ates of est_oa(t).Obvious cand idates are GAAP’s net oa(t), o r som e com bination o f oa(t)and oa(t-1).O f cou rse these num bers can be viewed as being in error due to m isapp licationsof GAAP,or problems inherent in GAAP itself,but the percentage error should generally be m anageable in the scheme o f things.The app roach actually provides amore critical advantage.It addresses the quality o f earnings issue solely focusing on whether the actual grow th in oa is too large/small relative to an independent estimate o f the grow th in oa,namelyΓ.

What about the second step,estimates ofΓ?Here the current grow th in sales revenues serves as a natural candidate.It is reasonably sim ilar in concep t to the Jonesm odelo f non-discretionary accruals,which in turn originates from traditional FSA analysis:the grow th in(operating)earnings is o f low quality whenever it exceeds the grow th in sales.In otherwords,generally speaking,an imp rovement in a f rm’s pro f tmargin does not give the sam ewarm feeling aswhen a f rm grow s its sales,though both o f these changes lead to im proved earnings.13W hen it com es to accoun ts receivable,the so-called“modifed Jonesmodel”makes an ad justment in them ajor independent variable, change in sales(norm alized by totalassets)to recognize the potentialaccrual classif cation of accounts receivable changes.In paper after paper,the Jonesmodel is recon fgured by deducting the change in accounts receivable from the change in sales.It seems like an odd reconfguration;rather than taking the change in accounts receivable,and deduct from the change in sales,it should of course be the change in the change in accoun ts receivable if onewants to ob tain the change in cash sales.(Analytically,the correction to change in sales should be(AR(t)-AR(t-1))-(AR(t-1)-AR(t-2)).)It also seems as if one ought to m ake an ad justment for deferred revenues.

Using sales grow th as an estimate ofΓone can estimate a GAAP-competing accrual:

accr(t)=grow th in sales(t)×est oa(t)

where est_oa(t)is either

oa(t)/(1+grow th in sales(t))

or

oa(t-1)

or som e weighted average o f the two num bers.

To m easure the grow th in operating activities using sales grow th does no t necessarily work all the tim e,o f course.A com pany that changes itsm arketing strategy from high m argin/p ricing to low m argin/pricing w ill increase its saleswithout increasing its investments.So the idea o fmeasuring grow th via sales revenues is by no m eans perfect,and,in fact,somewhat arbitrary un less one believes that the there has been no(material) change in the“true”p rof tmargin.Thisobservation concerning the lim its to using salesgrow th suggests that it can beworthwhile to consider alternativemethods that estimateΓ.

What are the alternatives to sales grow th?BecauseΓrefers to grow th of the operating business,onemay consider the grow th in capital expendituresasa grow th anchor.Thisapproach would seem to be quiteworkable as long asone can postulate that in the previous period the capital expenditureswere norm al relative to sales.But this p resupposition may be hard to validate,and the capitalexpenditures in the previous yearmay have been excep tionally sm all in which case the estim ated grow th w illbe biased upwards.To hand le thisobjection onem ay considerm easu ring grow th by look ing at capitalexpend itu res(net,the cu rrent period)relative to the dep reciation incurred.M ore general procedures that averages over the past capital expenditures anddep reciation charges can also be devised in attem p ts to m easure the“app rop riate”o r“better”accrual via a measure of the underlying grow th in the operating business.

The prob lem o f second-guessing a GAAP-based accrualw ith one’s own measurement is an intrinsically hard p roblem.W e can never know ifwe are com ing up w ith something better.That said,sometimeswe have good reasons to believe the GAAP accrual is potentiallymaterially distorted,as is the case when we believe that the com pany is,or hasbeen,applying so-called“big bath”charges.Now one’sown estimateo f an accrual m ightwell be an improvement.But ultimately this,too,is p lain conjecture unlessone evaluates its usefu lness empirically.

7.A discussion ofmethodologies that assessaccrualsempirically:Stock price based approaches

Supposewe can agree on how to classify the assets/liabilities into their two kindsw ithout controversy.Suppose further we have som emeasure o f accruals,either via GAAP or,say,some estimating p rocedure like grow th in sales times oa(t-1).Can we then evaluate if the accrualmeasurements are in formative?I think the answer is a qualifed yes.It has to be qualif ed insofar that one has to buy into some criterion as to what the desirable properties ought to be.

The accounting literature o fers a num ber of possibilities as to how one assesses the usefulness of accruals.In the spirit of Sloan’s early paper,as a f rst possibility one m ay consider whether GAAP accrualm easurem en ts allow us to m akem oney in the stock m arket.(One could also do this fo r non-GAAP estim ates o f accruals.)This criterion suggests the back-testing of portfolio strategies on the basis of accruals.14From thisobservation it should beapparent thatone cannot practically distinguish theaccrualanomaly from theso-called“investment anomaly”.Richardson et al.(2009)discuss the investment and accruals anomalies and their close connection.Fo r examp le,one can calcu late accrual-to-p rice ratios,keep cash earnings to price ratios constant,and then evaluate the returns for portfolio strategies that use this scheme to select long vs.short positions.As Sloan’s empirical results suggest,superior returnsm ight well be availab le,and,if true,this state of afairs is obviously o f great practical interest(to put it m ildly).15Thegrow th-accrual connectionm akes it presence felt in evaluationsof the(Sloan type)accrualanom aly:can it not instead bea grow th stock anom aly?See in particular Fairfeld et al.(2003)and the review paper by Richardson et al.(2009).From a more academ ic perspective,however,this app roach seems doubtful inso far that it runs counter to the discip lining hypothesis that the stock market is ef cient.A delicate issue lurks in the background.The possibility of making excess returns depends on the accrual being m isleading so that themarket potentially gets“deceived”and p rices thereby become ineff cient.But to say that an accrual is usefu l because others m isinterpret the accrual does not deal w ith whether the accrual is in form ative in a m ore trad itional sense that presum es hom ogenous and“accu rate”beliefs.

There isno need to rely on investm ent strategiesand the forecasting of returns to assess the utility or ro le o f accruals,whether GAAP or not.The huge literature on“value-relevance”can also guide the research.Specifically,accounting researchersconventionally rely on(cross-sectional)returns–earnings regressions to exam ine the value-relevance o f earnings and its components.(The returns,earnings and any other variab les on the RHS,are contemporaneous;the start-o f-period price scales the RHS variables.)App lying such value-relevancemethodology,one can thus regress annual cross-sections r(t)(market returns)on two variab les,cash earnings and the estimate o f the accrual(or,as a competing alternative,the GAAP accrual).One can then declare a degree o f success if both the estimated coef cients achieve statistical signif cance and they exceed one.G reater than one isessentialsince it shows thata do llar of cash and a dollar of earningsareat leastworth a do llar in them arket.An even better resu lt is ob tained if add itionally the estim ated coef cients are(approxim ately)the sam e for the two independent variables.Such a fnding m eans that the two earnings components aggregatewithout loss of information,an essential feature of“good”accounting.

One can also consider an accrual constructbased on amodel that competesw ith a GAAP-based accrual.In such a regression the related two independent variab les,cash earningsand themodelaccrual,one can hypothesize that the related R2exceeds those that are associated w ith GAAP earnings or a regression w ith cash earnings plus GAAP accruals on the RHS.If signif cant,the resu lt points toward themodel accrual being more informative than the GAAP accrual.Yet another horse race between amodel based accrual constructand GAAP accruals puts these two accrual variables com bined w ith cash earnings on the RHS of the regression to explain returns.One then evaluateswhich o f the two com peting accruals contributes themost to the R2.

Is it likely thatmodelaccrualswork better than GAAPaccruals in regressionsexplaining returns?It ishard to say,especially since there aremore than a few devils in the details,i.e.,how to measure the cash earnings and the estimated model accrual.There are also all kinds o f specif cation issues,like the ro le of expectations and other potential confounding variables.But it certainlywould seem to beworth a try to pursue these kinds o f research hypotheses.

What about the possibility that the R2is disappointing because the stock market happens to be,in fact, inef cient?To hand le this problem one can sim p ly add yet another RHS variable to the retu rns-earningsaccruals regressions,nam ely,the subsequen t period’sm arket return,r(t+1).This add itional variab le w ill f lter ou t the noise in the contem poraneous retu rns-earnings regression due to any m arket inef ciencies as m anifest in the predictability o f future returns.16Ifone assumesmarketef ciency in itsweak form–themarket returnsareserially uncorrelated,corr[r(t+1),r(t)]=0–then r(t+1)on the RHS in the regression loads if and only if it correlatesw ith the remaining variables(date t)on the RHS.Hence themarket is not ef cien t in the so-called sem i-strong form since date t variables correlate w ith the subsequent returns.The general prob lem of value relevance and correcting for inef cien tmarkets is extensively discussed by Aboody et al.(2002).

8.A discussion ofmethodologies that assess accruals empirically:W ithout reference to stock prices or returns

Sloan and others consider the problem o f how one tests empirically whether(GAAP)accruals appropriately inform investorsw ithout referring to stock prices(or returns).He argues that GAAP accruals tendency to reverse requires a separation of accruals and cash fowswhen one forecasts subsequent earnings.Specifcally,because accruals hypothetically have lower persistence than cash f ows,in the forecasting equation the accrual should have a lower weight as compared to the weight on cash earnings.The idea exerts a pull in fnancialanalysis since it suggests that accruals canm isin form if added to cash earnings.Having said that, one still has to keep in m ind that the setting isnot as straightforward asonewou ld like because a cross-sectionalsetting requiresa defation of thevariab les to adjust for size.Sloan picks totalassetsas the def ator variab le.One can thus think of Sloan’sapproach as add ressing a p ractical p rob lem that forecasts ROA using two independent variables,cu rrent cash earnings defated by total assets and the curren t accrual also defated by total assets.As a d rawback,the forecasting of ROA does not seem to be prom inent in practice.

Focusing on practical problems,onemay consider forecasting the change in f rms’(operating)pro f tmargins per GAAP.It iso f obvious practical interest since analysts tend to forecast operating earningsvia a forecast of sales grow th combined with an(operating)p rof t margin.But this forecasting perspective also add resses the issueo f thequality of(current)earnings.If current earningscan be identifed aso f poor quality, then such an evaluation leads to the forecasting o f a decline in the future pro f tmargin.Thus the operating p rof tmargin can serve asa usefu l dependent variab le because it con fronts the quality of earnings issue head on yet it isalso of p ractical interest.And now one naturally extends the analysis to check whether competing accruals(like those p reviously d iscussed)can aid in the forecasting o f the change in the operating pro f tm argin.To be specif c,does the d if erence between a GAAP accrual and a m odelaccrual facilitate the fo recast o f change in the GAAP p rof tm argin?

9.Assessing reversals empirically

The pro f tm argin com p rises two parts:the cash m argin(cash earnings scaled by sales)and them argin due to the accrual component.This simp le observation suggests that one can evaluatewhether the accrual componenthasa negative serial correlation,i.e.,it reverses.(One can use a linearmodelor an n by n contingency table to evaluate thisempiricalhypothesis).Thisanalysis looks reasonab le enough,yet it isunsatisfactory in a cross-sectionalsetting.The reason is that for grow ing f rmsone should expect positiveaccruals to be fo llowed by positive accruals;for non-grow th f rms low accrualsshou ld be fo llowed,on average,by low accruals.This m erely amounts to saying that the reversal property in the accrualmargin doesnot f t a cross-sectionalmodeof analysis because there has been no ad justm en t fo r trends varying in the cross-section.In other wo rds, looking at accrualsover two ad jacent years for a large num ber of f rms cannot tell usm uch about reversals. Statistical power has been lost.

Sowhat can bedone ifwewant to analyze reversals in a cross-sectionalsetting?Answer:weneed amodelo f what a f rm’s accrual ought to be in any given period.Thus,to implement the statistics,one relies on the observation

{accr(t)per GAAP}/sales(t)m inus{accr(t)per M odel}/sales(t)

where the“per M odel”corresponds to whatwas discussed in a p revious section,namely,in a base case,put accr(t)per M odel=growth in sales(t)·oa(t-1).In thisway of looking at the problem,under the alternative hypothesis the reversal direction of the GAAP accrual can be assessed by looking at the sign of the actual accrualm inus the model accrual;pluses are fo llowed by m inuses and conversely(on average).Now one has a framework to exam ine the reversal in a cross-sectional setting,but at the“cost”of having to maintain an assump tion on how the“correct”accrual should bemeasured.17M ore generally,the probability of seeing a negative GAAP-accrualm inusmodel accrualshould depend on the extent to which there has been a positive observation not on ly in the p revious period but also in periods prior to the previous one.

Another,perhapsmoredirect,approach simp ly looksat the grow th in oa(t)per GAAP and usesgrow th in sales as the benchmark.Thus the unit o f observation for purposes o f statistics reduces to

{oa(t)-oa(t-1)}/oa(t-1)m inus{sales(t)-sales(t-1)}/sales(t-1)

A hypothesis o f reversals now implies that these observations have a negative serial correlation:negative values tend to be followed by positive values w ith a p robability greater than 50–50.And this test can be app lied for any 2 adjacent years in an n by n contingency tableor,alternatively,asa simp le(rank)correlation. Thisway o f looking at reversals takesusback to very traditional FSA:The change in a f rm’sso called asset–turnover p rovidesan indicator o f the quality o f earnings.18Changes in ATO(sales divided by oa)acting as a leading indicator of changes in earn ings haves been assessed by Fairf eld and Yohn (2001).Again,many papers dealing w ith FSA issues can be thought o f equally well as dealing with accrual reversals.A drawback w ith thisapp roach is that itmay not work wellwhen sales relative to oa is large;it could createexcessvolatility in thegrow th in oa as compared to the grow th in sales.And of course,there are issues involved insofar the oa-grow th should precede the sales grow th;an assum p tion that the two grow th m easures shou ld m ove con tem po raneously m ay be too stringent.19One can ask whether reversals in accruals relate to Basu’s conceptof(conditional)accounting conservatism.Though theanalysisneeds to bewo rked out,itwould seem so.The reason is that bad news tends to correlatew ith w rite-of s,and w rite-of s lead to signif cantnegative accruals(on average),which in tu rn would clear the deck fo r subsequent positive accruals.

Should one conclude predictable,and material,reversals in GAAP’s accruals refect either earnings managem ent(in the spirit of Jones’s“discretionary accruals”)or poor accounting standards?As to earnings managem ent,I think not.As to poor accounting standards,I think atmost“maybe”.The point that needs to be appreciated is the possibility o f non-recurring items(or special items to use a dif erent jargon).These items can o f course be present in both accrualsand cash earnings(not tomention earnings),but there are good reasons to hypothesize that they aremuch more pervasive in accruals than cash earnings due to w rite-o fs and restructuring charges.If such is indeed the case,then itmakes sense to hypothesize that the non-recurring itemshave amaterial impactand possib ly compel empirical results in favor of a reversal conclusion.But special item s do not necessarily ref ect earningsm anagem en t since they generally are consistentw ith GAAP.And they refect“bad”accounting on ly if one now buys into the p rio r proposition that GAAP is too lenientwhen it com es to the use of special item s.Stated som ewhat diferently,if onem akes the case that sound accounting shou ld leave amp le room for non-recurring itemswhen one accounts for operating activities,then there are reasons to expect that the period’s net accrual reverses.

10.Some implications for future research

Asnoted in the introduction,it isoutside thescopeo f thispaper to critically evaluate the(essentially empirical)literature on accruals.The task wou ld have been as form idab le as tricky inso far that it isall too easy toslip in to d iscussions o f issues that are relatively m inor in the overall schem e of things.It is probably m o re worthwhile to look toward future research.In thisspirit Iw illstatewhat Iview assome of themoresignif cant imp lications related to p revious discussions.I do not claim novelty;no doubt a carefu l literature review w ill f nd papers that comevery close tomaking argumentsnotall that dif erent to those stated below.M y choiceo f pointsmade depends primarily on the extent Ibelieve they can usefu lly guide research on accruals w ithout concern given to specif c topics.

·In dealingw ith accruals itmakessense to alwaysuse,asa starting point,the framework that recognizes comp rehensive earnings and(comprehensive)cash earnings as reconciling w ith the net accrual.To im p lem en t this approach it helps to clarify which particu lar assets/liabilitieshave been classifed as cash vs.those that are operating.Follow ing that a researcher m ay well in troduce som e m easure o f“cash fow s”to distinguish these from cash earnings.Thusa researcherm ay,fo r exam p le,concern herselfw ith“cash p rovided by current operations”(as he/she chooses to def ne it)and in a complimentary fashion identify the related accruals.This app roach shou ld paint a coherent picture;it allows a reader to see more clearly the constructandmeasurements thatm otivate the research design.From a broad perspective,the issue athand is:what should be the generally understood fram ework when dealingw ith accruals?If comprehensive earnings and cash earnings are not the core ingredients,then whatmakesmore sense?

·Researchershelp readersbymaking it clearwhether they rely on the“apples”and“oranges”metaphor to set the stage for the research question.In otherwords,is it crucial that theaccrualsand cash earnings m ay not add because itwou ld lead to signif can t loss o f info rm ation?If this them e is expanded on,like in research settings that bear on value relevance orm arket inef ciency,a researcher can ef ectively communicate research objectivesormaintained hypotheses.Italso helps if the researcher spellsoutwhether theapp les&oranges dichotomy dependson a particu lar context(such as thep resence ofw rite-o fsor a f rm going to the capitalmarket to obtain additional fnancing)or app liesmore broad ly.

·In case there isa need to defate/scale accrualsor cash earnings,a f rm’s sales revenue seems preferable to its totalassets.The argumenthere is that a f rm’s(operating)pro f tmargin iso f great interest in the fnancial community.The same cannot be said for ROA.M oreover,the forecasting of the prof tmargin,and its two components(cash margin and accrualmargin),in terms of current accrual diagnostics can become part o f quality of earnings research.It also naturally comp lements grow th in saleswhich p lays such a crucial role to understand the cash earnings/accrualm ix.

·Research that concerns itself w ith“bad”accruals,such as“reversals”and“quality of earnings”issues, can help the reader by suggesting how onem igh tm easure an accrual so it becom esm ore info rm ative. That is,this task addresseswhat efective f nancial statement analysis should look like as a p ractical matter.The research can also spell outwhy,orwhy not,itmakes sense to evaluate competing accruals as to their information content or other properties.

·A researcher helps a reader by stating whether the setting invokes a perspective where themeasured accrual corresponds to a m easurement of the grow th in a f rm’s operating activities,and operating activities alone.It is amatter o f avoiding confusion since one can reasonab ly argue that,in fact,there are accruals related to fnancial activities.

·Finally,given the enormous increase in the literature on accrualsand the high likelihood of seeing no abatem en t in the future,it helps if the researcher spellsou t his/her concep to f an accrualand how itm ay difer from alternative useso f the term.Nobody hasam onopoly on how to use accounting jargon,and thus the need for clarity has escalated as the literatu re has grown.

11.Concluding remarks

M ost discussionso f accruals tend to have a negative tenor and rarely do they fail to m en tion the dangerso f in terpreting accruals as cash equivalents.In an extrem e view accruals purported ly act as“noise”due to the arcane/arbitrary histo rical cost accoun ting rules inheren t in GAAP:as a consequence accruals are best dism issed.Finance texts occasionally still espouse this view,though of course most accountants would argueotherw ise.W hile academ ic accountants generally adm it that accruals can bem isleading,on average accruals provide useful information as indicators of future cash fows and earnings that go beyond the information in current cash earnings.As Sloan and many othershave argued,the-num bers-do-not-add qualif ermeans that fnancial analysisbenef ts from splitting earnings into their cash earningsand accrual components.That said, it iswell to note that at least in p rinciple one can visualize a third perspective,namely accruals that do not reverse;in otherwordsunder such idealized conditionsaccrualsadd to cash earningsw ithout lossof in formation.How to implement such accounting isan open question,though Ihope some of the pointsmade in this paper p rovide a sense of direction abouthow itmay be done.It goes to theheart of accountingwhen itworks at its best:what does it take to ensure that the bottom line need not be split into components?The question would seem to be interesting not only as a m atter of accoun ting theory but also asm atter of dealing w ith quality o f earnings issues.To app reciate this third perspective on accruals,one can even consider a fourth possibility which is rarely hypo thesized.Under som e circum stancesone can argue that earnings shou ld be sp lit into its two components because a dollar of an accrual is worth more than a dollar of cash earnings.This possibility arises in settingsw ith conservative accounting and grow th in expected operating assets.20Feltham and Ohlson(1995)provide su f cient assum ptions.

Aboody,D.,Hughes,J.,Liu,J.,2002.M easuring value relevance in a(possibly)inef cientmarket.J.Account.Res.40,965–986.

A llen,E.,Larson,C.,Sloan,R.G.,2009.A ccrual reversals,earnings and stock returns.J.A ccount.Econ.56,113–129.

Dechow,P.M.,Dichev,I.D.,M cN icho ls,M.F.,2002.The quality of accrualsand earnings:the roleof accrualestimation errors.Account. Rev.77,35–59.

Dechow,P.M.,Ge,W.,Schrand,C.,2009.Earnings quality and earningsmanagement.J.Account.Econ..

Easton,P.,M cAnally,M.,Fairfeld,P.,Zhang,X.,2009.Financial Statemen t Analysis and Valuation.Cam bridge Business Publishers.

Fairfeld,P.M.,Yohn,T.,2001.Using asset turnover and pro f tmartin to forecast changes in p rof tability.Rev.Account.Stud..

Fairfeld,P.M.,W hisenant,J.S.,Yohn,T.L.,2003.Accrued earnings and grow th:im plications for future prof tability and market m ispricing.Account.Rev.78,353–371.

Feltham,G.,Ohlson,J.,1995.Valuation and clean surp lus accoun ting for operating and fnancialactivities.Contem p.A ccount.Res.11, 689–731.

Hribar,P.,Co llins,D.W.,2002.Errors in estimating accruals:im plications for empirical research.J.Account.Res.40,105–134.

Jones,J.,1991.Earningsmanagement during im port relief investigations.J.Account.Res.29,193–228.

M elum ad,N.,N issim,D.,2009.Line-item analysis of earnings quality.Found.T rends A ccount..

Oh lson,J.,Aier,J.K.,2009.On the analysiso f f rm s’cash fows.Contem p.Account.Res.26,1091–1114.

Penman,S.,2009.Financial Statements Analysis and Security Valuation,fourth ed.Irw in M cG raw Hill.

Penman,S.,Zhang,X.,2002.Accounting conservatism,the quality of earnings,and stock returns.Account.Rev.77,237–264.

Richardson,S.,Tuna,˙I.,W ysocki,P.,2009.A ccoun ting anomalies and fundam ental analysis:a review of recent research advances.J. A ccount.Econ.50,410–454.

Sloan,R.,1996.Do stock prices fu lly refect information in accruals and cash fows about future earnings?Account.Rev.71,289–316.

E-mail address:johlson@stern.nyu.edu

Production and hos ting by Elsevier

1755-3091/$-see frontmatter©2014 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of China Journal of Accounting Research. Founded by Sun Yat-sen U niversity and City U niversity of H ong Kong.

h ttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2014.03.003