李晓东访谈

2014-02-21凯特古德温KateGoodwin

凯特·古德温/Kate Goodwin

尚晋 译/Translated by SHANG Jin

李晓东访谈

Interview with LI Xiaodong

凯特·古德温/Kate Goodwin

尚晋 译/Translated by SHANG Jin

李晓东

1984年毕业于清华大学建筑系,1989-1993年赴荷兰留学,就读于代尔夫特理工大学获博士学位。目前为一位实践建筑师、教育者及研究者。

李晓东的设计领域包括室内、建筑和城市空间,曾获多个国际级奖项:“桥上书屋”项目获得2009年英国《建筑评论》杂志世界新锐建筑奖优胜奖、2010年阿卡汗建筑奖优胜奖、2012年英国《泰晤士报》世界八大环保建筑奖;“篱苑书屋”项目获得2012年新加坡世界建筑节年度文化建筑类优胜奖、2013年瑞典“建筑的必要性国际宣言”国际可持续社区建筑优胜奖;“玉湖完小”项目获得2004年英国《建筑评论》杂志世界新锐建筑奖特别推荐奖、2004年美国环境设计与研究协会年度最佳设计奖、2005年联合国教科文组织亚太区文化遗产评审团创新奖、2005-2006年亚洲建筑师协会建筑奖——亚洲建筑金奖、2006年美国《商业周刊》/《建筑实录》中国最佳公共建筑奖。2011年,李晓东被《智族GQ》杂志评为中国年度最佳设计师;2012年,被美国建筑师协会授予荣誉院士。

李晓东作为建筑教师,于1997-2004年执教于新加坡国立大学建筑系,曾获得2000年RIBA导师奖及2001年SARA导师奖。2005年,他回到清华大学建筑学院任教授至今,研究领域包括建筑文化、历史与理论以及城市研究等。

LI Xiaodong

Graduated from School of Architecture at Tsinghua University in 1984 and did his PhD at the School of Architecture,Delft University of Technology between 1989-1993,is a practicing architect,educator and researcher on architecture.

LI Xiaodong's design ranges from interior,architecture to urban spaces,he has won both national and international awards,among which: his design for Bridge School in Fujian Province was the winner of 2009 AR(review) Emerging Architecture Award and winner of 2010 Aga Khan Award for Architecture,2012 Eight Sustainable Architecture,Times (UK); his Liyuan Library (Wattle School) was the winner of culture category of 2012 WAF in Singapore and winner of 2013 Architecture of Necessity in Sweden ; his Yuhu Elementary School won 2005 UESCO Jury Award for Innovation,2004 EDRA/Places Annual Design Awards (US),2004 AR+D Awards (UK) highly commended,2005-2006 ARASIA Gold Medal,and 2006 Business Week/Architectural Record China Awards Best Public Building LI Xiaodong was awarded man of the year in China (best designer) in 2011 by GQ magazine,and was awarded the Honorary Fellowship by AIA in 2012.

He also teaches architecture,he has won prestige international awards: RIBA tutor's prize (2000) and SARA tutor's prize (2001) for his inspirational teaching at the Department of Architecture,National University of Singapore Since 2005,he has been the chair professor of the architecture program at the School of Architecture,Tsinghua University,in Beijing He is also a researcher,his publication in articles,books in both English and Chinese covers wide range of interests,from cultural studies,history and theory of architecture to urban studies.

1 中国古画中游鱼/Swimming fishes in a Chinese painting

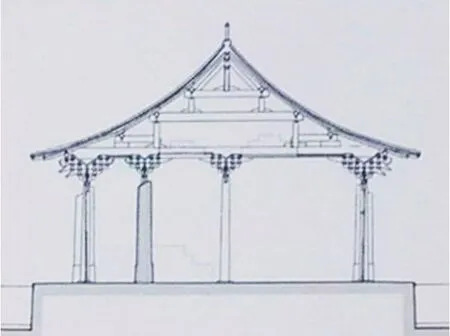

3 古建筑剖面,表现中国建筑传统元素/Section showing the traditional elements of Chinese architecture

凯特·古德温(古德温): 你曾写过一本题目是《中国空间》的书。你是不是认为中国的文化对于空间的理解有一些特别之处呢?

李晓东: 这本书源于一个中西方空间概念对比的研究。我发现二者有明显的区别:西方倾向于把世界看作一系列对象,而我们在中国和东方不大区分主客体。西方建筑从透视学发展而来,把建筑当作从“外”去看的对象。中国建筑的理念是从“内”去体验。

在中国的传统中,空间是在一个明确的体系内表达的,在不同的语境中可以通过想象(而不是逻辑)进行再阐释。这种再阐释的可能性使文化成为可持续的——就像中国的汉字,虽是数千年前创造的,但在今天仍是活的语言。中国人重道而轻器——这一点你从国画中就能看到,留白与着墨是同样重要的。比方说,画一对游鱼,水的存在是从白背景中意会出来的,而这是画面中非常重要的一部分。因此,要实现令人满足的空间体验,就必须为观者的想象留出空间。

我们还可以从中西方表达建筑的传统上看到这种区别。在中国,人工创造的空间首先是形而上的,应当与大自然的秩序和谐。中国文化对空间的营造是与绘画、书法和诗歌并列的艺术。明清私家园林就可以证明这一点。

古德温:你认为当代建筑怎样才能把中国传统文化与现代结合在一起呢?

李晓东:中国建筑的技术语汇早在汉代就已确立,有柱、梁和三四种不同形式的大屋顶。两千年过去了,变化的只有色彩和空间。所以, 在中国的传统中,建筑的问题不在于单体造型,而是如何用相邻的房屋来限定空间。

比如,紫禁城的魅力就在于层层递进的空间体验,而不是某个大殿。在这一点上,老子就认为重要的是“用”而不是“器”。中国传统的合院住宅也是一个很好的例子。

现代建筑是西方创造的,我们中国要吸收这种新的思想。梁思成是中国现代建筑之父,也是清华大学建筑系的创立者——我就是那里毕业的。他的教学理念就是要把中国的传统和知识与现代的形式熔为一炉。这无疑是我们探索民族特色与现代性之间关系的重要一步。但我的问题是:如果中国建筑自古就与“形式”无关,那我们又怎能将中国的传统形式现代化呢?

我的大量研究和设计工作都集中在两点上:我们能否用古代文化丰富当代建筑的理论和实践;中国传统概念如何以现代手段表达。这就是关键所在:我们需要找到我们的建筑发展道路,而不是模仿西方造型或者硬套中国传统形式和装饰。

古德温: 这些思想是怎么在你的实践中体现的呢?

李晓东:在我看来,过去的100年是建筑构造语汇形成的时代——现代主义、后现代主义、解构主义等等。理论和争辩带来了实用的语汇,但21世纪的全球化和文化碰撞改变了问题的焦点。所以,我认为今天的建筑应该用实际情况重新整合这些思想。

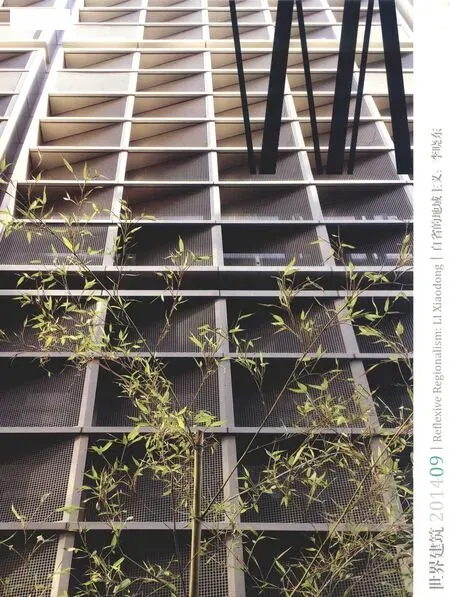

我在实践中的努力可以称作“自省的地域主义”,也就是更关注发现本原而非原创形式。

例如,我在巴厘设计的会议中心,通过结合现代功能与传统材料和文化,营造出地域的归属感。在热带丛林中,秩序对于人类居住地是首要的,而我的设计就是从这一原则出发的。比如,当地建筑用竹子遮阳——这是功能性的——而这种材料的韵律更体现出巴厘村庄的秩序感。所以,重点是结合技术、地方材料、现代思想和传统的认同感。

古德温:你已经谈到建筑与环境之间的关系对于你作品的重要性。那你第一次意识到环境的空间内涵以及你可以在其中发挥的作用是什么时候呢?

李晓东:1984-1986年在黄山的经历打动了事业刚刚起步的我,那时我正在负责一座酒店的建设。变幻莫测的天气、深远恢宏的尺度,以及我对造山运动的历史跨度的慨叹,都推动着我的观念向前。

远望群山,你会看到连绵起伏的一条轮廓线。而一旦走入山中,你又会发现它是在你身边连续不断的空间关系。你对尺度、距离、质感和围合的意识在一瞬间觉醒,让你在其中感受到自我的存在。这是最美妙的一刻。

古德温:你可以说一说这种感受对你作品的具体影响么?

李晓东:这个从淼庐和篱苑书屋上都能看到。它们所体现出来的都是建筑与周边环境的关系,而不是一个孤立的建筑。

淼庐和玉龙雪山的环境是一体的。建筑与景观相得益彰,进而提高了整体环境的品质。这就像是一个系统,各部分之间的关系大于任何个体;或者说是一个万花筒,系统的整体性发挥着主导作用,而各要素的价值会被略去。

篱苑书屋的目的是建立一个平台,让人们去欣赏自然环境。它很单纯,因为单纯更能让人感悟自然。

Kate Goodwin (KG): You have written a book called Chinese Conception of Space Do you feel there is something very particular about the ways your culture understands space?

LI Xiaodong (L): The book began as a research project comparing concepts of space in China and the West I found that there is a clear distinction: the Western tendency is to look at the world as a series of objects,while in China and the East we tend not to differentiate between subject and object So Western architecture develops from perspective,with the building understood as an object to be looked at from "without",while Chinese architecture develops from the idea that the building is something to be experienced from "within".

In Chinese tradition,space has been articulated within a defined framework that allows for reinterpretation in different contexts using imagination rather than through logic This possibility of reinterpretation is what makes the culture sustainable - it's like the characters in Chinese writing,which were created thousands of years ago but still form part of a living language.Chinese tend to focus on? the intangible rather than the tangible - you see this in Chinese painting,in which the blank surface is often just as important as what is inscribed For instance,in a painting that shows a pair of swimming fish,the presence of water,which can be inferred from the blank background,is a vital part of the image Allowing room for the visitor's imagination is essential if a space is to become a satisfying physical experience.

We also see a difference between Chinese and Western ideas in the way architecture has been represented by the two traditions For the Chinese,an artificially created space is first of all cosmological and should be in harmony with the order of nature.The articulation of space - as in the history of private garden design from the Ming and Qing dynasties -has been regarded by Chinese culture as an art form alongside painting,calligraphy or poetry.

KG: In what ways do you think contemporary architecture can bridge the gap between traditional Chinese culture and present-day conditions?

L: The technical language of Chinese architecture was already defined back in the Han Dynasty,about 2,000 years ago There were columns,beams and then a big roof,with three or four different roof types For the next two millennia,the only changes were to do with colour and space So in the Chinese tradition,architecture is less about individual building forms than about how space is defined by the structures that surround it.

The Forbidden City,for instance,is about experiencing space after space after space rather than appreciating individual buildings It's a concept articulated by the Ancient Chinese philosopher Laozi,who said that what is important is what is contained,not the container This is also exemplified in the courtyard typology of traditional Chinese housing.

Modern architecture is an invention of the West,and we Chinese have had to adopt this new way of thinking.Liang Sicheng,the "father" of modern architecture in China and the founder of the Architecture Department at Tsinghua University where I was trained,based his teaching on ways of combining Chinese tradition and knowledge with modern forms.This,of course,was an important stage for us in discovering relationships between identity and modernity But the question for me is: can we really modernise a traditional Chinese form if Chinese architecture has never been about form?

Much of my own research and design work have been focused on exploring whether contemporary architectural theory and practice might be enriched through dialogue with our ancient culture,and how the concepts of Chinese tradition might be expressed in modern ways This is what matters: we need to find ways of developing our architecture without aping Western models or relying on a superficial imitation of traditional Chinese forms and decoration.

KG: How are these ideas manifesting themselves in your own practice?

L: It seems to me that the last hundred years have been about the development of tectonic languages of architecture - Modernism,Postmodernism,Deconstructivism and so on Theory and debate have created a useful working vocabulary,but in the twentyfirst century globalisation and cultural conflicts have changed the issues.I think architecture today should try to reintegrate ideas with real-life conditions.

What I am trying to do in my own practice might be described as "reflexive regionalism." It's more about identifying original conditions than inventing original forms.

To take an example,my project for a conference centre in Bali creates a sense of regional identity by mixing modern functional thinking with traditional materials and culture In the tropical jungle,order is of primary importance for human settlements and my design grows from that principle For instance,local buildings use bamboo to filter the light - it's a functional thing - but the repetition in the material also reflects the sense of order you find in Balinese villages So it's about combining technology,local materials,modern thinking and a traditional sense of identity.

KG: You have described how key the relationship of building and environment is to your work Can you recall a moment when you first became aware of the spatial potential of the environment and your place within it?

L: A formative experience from the start of my career was my stay from 1984 to 1986 in Huangshan (the Yellow Mountain range) while I was supervising the construction of a hotel The changing seasons and weather,the distances and dimensions,as well as my consciousness of the vast timescale of the mountains' creation,all contributed to a change in my perceptions.

From a distance you think of a mountain range as a series of objects seen in silhouette But once you are within it,you start to perceive it as a series of spatial relationships that surround you Your awareness of scale,distance,texture and enclosure all come alive and you become conscious of your own presence within it Recognising this was a beautiful moment.

KG: Can you identify any influences of this experience within your own work?

L: Both the Water House and the Liyuan Library reflect the impact of this experience They are about the relationship of a building to its surroundings rather than a building as a discrete object.

The architecture of the Water House is integrated into the setting of the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain House and landscape complement each other so the quality of the whole environment is improved It's like a system within which the relationships between the parts are more important than the parts themselves - a kaleidoscope,where the integrity of the system predominates and the significance of the individual elements disappears.

With the Liyuan Library ,the intention was to create a framework that would help you to appreciate the natural environment It is simple because simplicity allows you to appreciate nature more readily.

I have discovered that if a building is too complicated,you risk diluting your intentions The amount of detail you can generate through computer drawings is wonderful,but you need to have a consistent and simple way of using those details When I'm working I need to be clear about the issues before I can generate ideas.Solutions emerge from a clear definition of the problem It's not about the details but rather about how you respond to and create a total environment.

KG: What role do you think the senses play in how we experience space? And how might this add to how we engage with architecture?

L: There are millions of sensors all over our bodies,taking in information about our environment and transmitting it to our brains They're like radar,scanning our surroundings and sending back signals The information we receive can't be quantified,so how we engage with these perceptions to create architecture is difficult to define.

4 紫禁城鸟瞰/Aerial view of the Forbidden City

5 北京紫禁城穿过大门和庭院的轴线/Axial view through protals and courtyards of the Forbidden City

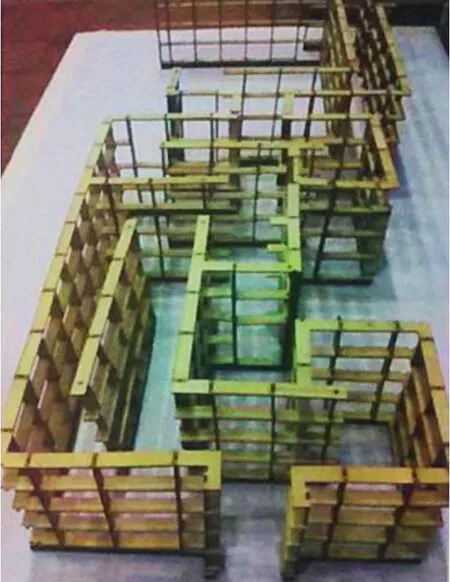

6 感知空间展览设计模型/Model,"Sensing Space" exhibition

在我看来,一个建筑要是太复杂,就会弱化设计的主旨。用计算机可以做出很多好的细部,但你需要统一而单纯的手法来运用这些细部。我在工作的时候就会先明确问题,然后再发挥创意;方案就会在所确定的问题中形成。关键不在于细部,而是你如何呼应并创造一个完整的环境。

古德温:你认为感官在我们的空间体验中能起到什么作用?这对我们把握建筑又有什么帮助?

李晓东:我们的身上有无数的神经细胞,把环境中的信息送入大脑。这就像雷达一样,不断地扫描并反馈信号。我们收到的信息不是量化的,所以很难确定我们如何用这些感觉来创造建筑。

我从21岁起就练太极,锻炼自身的感官系统。太极讲究内外兼修,调理气息,以强健体魄。但它又不只是修身,还有养心,让人的感官更加敏锐。

通过练太极,我也更容易感受到气场这种物质元素的系统关系与和谐所带来的能量流。对于中国人来说,这种永恒的能量在万物中流动、不断改变宇宙的观念是非常重要的。所以,我在项目开始时做的第一件事就是分析场地和它的气场,然后用建筑师的手法把我的发现转译到设计中。

古德温:你作为建筑师对于空间的理解和认识还有其他独到之处么?

李晓东:建筑师的工作要充分结合理性、直觉和经验的作用。当空间赋予你某种感受时,你会去寻找其中的原因,而这个答案就会成为你自己的语言。有时它是对空间的批判分析,会成为你自己的理解,并可以在将来用到。“光线不错,尺度适宜,材料别致”,这样的认识都是需要积累的。你所到过的每个地方都会触动你的心灵,让你去探索更多的可能。经历越多就越开放,这就是我的心得。

古德温:有没有一个空间或建筑特别能让你意识到自我和环境,尤其是“在场”?

李晓东:我最近去纽约州的布法罗做过一次演讲,住在赖特设计的达尔文·马丁之家。赖特在我心中是第一个关注空间而非建筑实体的西方建筑师。

在赖特设计的住宅中漫步,就是在体会他的设计思想。由于他是从自己的住宅和工作室的建筑实验中学习建筑的,所以他能够清晰地理解“现实”和“概念”。这就是融入空间的“在场”与身心异置的空间图像之间的根本区别。

路易·康的金贝尔美术馆是另一个例子,你可以从它的空间中感到所有的元素都是围绕着一个整体——建筑、空间、光线、展品和置身其中的你。这就像阴阳:没有阴,就没有阳。

古德温:你认为还有什么方式能让建筑影响或改善人的体验?

李晓东:空间的认知需要想象与现实之间的对话。这就像作家在写故事——他们用想象力演绎自己对现实的体会。

中国的文学点明了建筑在我们生活中的重要性以及我们与它的关系。各种典故都以建筑作为叙事的背景,而中国建筑又映射着文学的体验。中国的诗歌通常开篇就设定时空,没有这个具象的环境就很难表达文意。可以说,中国文学里的每个故事都有“场所”。

中国的故事往往会给某个特定的空间赋予特殊的意义,这就决定了其中的人如何在相互之间发生关系,所以,空间在决定了一种社会模式的同时又描述了它。中国文化需要在时空和社会中把握人的位置,而有形的空间参照体系是这一过程所必需的。还拿紫禁城来说,你要在连续穿过五六座大门之后才能看到大殿。每个内院的长度都不相同,于是这种序列就形成了一种特殊的动势。门槛也表达了不同程度的私密性,有宫廷则例规定了门槛的高度或门钉的数量,而这取决于官员的品第。

古德温:英国皇家艺术学院也有类似的空间序列体验:从喧闹的皮卡迪利广场到安纳伯格庭院,进入17世纪的市政厅,再经过大台阶到19世纪的主厅。你的装置如何与这种递进的空间和界限结合?

李晓东:这已经是一个非常丰富的序列。街道上不仅材质和声音不同,人群的背景也不同。而到了厅内又十分纯粹。

一旦你进入装置,我希望给人一种发现之旅,让观众感到有另外的世界在伴随着他们,并与之交汇穿插。不是路上所有的东西都清晰可见,而是像中国的画卷一样展开,让人在时间中体会这段故事。最后,连续的印象将在人们心中形成一幅新的画面。

古德温:你能详细说一说这个设计的构思么?

李晓东:感觉上你仿佛是在雪夜穿越林海,而这是通过细树枝的迷宫和底面被照亮的地板来表现的。在前进的路上,你会发现给你希望和惊喜的小空间。在迷宫的尽头是禅院,代表灵感与启示。从认识论的角度看,它让你去看、去悟,变“昧”为“明”。

我用树枝是因为这种天然的材料不是建筑上常见的,把人们熟悉的材料以不寻常的手法用在不寻常的环境里会带来特别的效果。当你创造的时候,往往需要的不是原创性本身,而是实际应用和再利用。在乡村,你可以试着用树枝融入自然;而在伦敦,是要在人工环境里营造看似自然的环境。

我还在禅院里放了一面镜子,因为它可以改变空间的感觉。它没有墙体的实在,而是呈现他物的幻象。即便是一个围合的空间,镜子也能让它感觉很大。镜子还经常出现在风水中,而那是与环境和气场有关的。

古德温:你提到过用空间的对比给观者的“意识一刺”,这要如何实现呢?

李晓东:这个装置的核心概念与伦敦的关联或者说非关联在于,通过陌生化刺激人的意识。

这个效果在很大程度上来自随空间移动而变化的氛围。一开始,材质和尺度都很明确、很熟悉,同时又有一种迷失。到了禅院则是一种豁然开朗。这种对比和空间中的气场让人反观自身的感受,使意识得以升华。

古德温:你为这次展览设计装置的方法与平时的工作有什么不同?

李晓东:大多数建筑项目都有具体的功能要求,而展览更关注审美的体验。一方面,这更容易了,因为你不需要考虑实际的问题;另一方面又更难了,因为你要创造一个吸引人的空间——他们想要点什么却又说不出来。对于我来说,主要的问题是怎样激发人们的好奇心,并带来想要的效果。

I've been practising tai chi since I was 21 to strengthen my sensory system Tai chi is about looking inwards as well as outwards; it's a system of breathing and energy flow that makes you stronger and more powerful It's not just physical; it's about focusing the mind through which all your senses become more alert.

Through tai chi I also train myself to be more receptive to what we call qi,a flow of energy made possible by the systematic relationship and harmony of physical elements For the Chinese,this idea of energy forever circulating,flowing through all things and continually transforming the cosmos,is very important So when I start working on a project,the first thing I do is analyse the site and the flow of energy through it Then with my training as an architect I hope to translate my findings into designs.

KG: What else do you think is distinctive about how you as an architect understand and perceive space?

L: Architects work through reasoning,instinct and experience and then put the whole thing together When a space makes an impression on you,you ask "why?",and the answer becomes part of your vocabulary Sometimes it's a critical analysis of space that you incorporate into your own understanding for future use Things like,"this lighting is good," "these dimensions work," and "this material is interesting" are perceptions you store up to explore later.Every place you visit generates puzzle pieces in your mind and you develop a palette of possibilities I find that the more experiences I have,the more open to possibilities I become.

KG: Can you recall a space or a work of architecture that has made you particularly aware of yourself and your surroundings,particularly "present"?

L: When I recently gave a lecture in Buffalo,New York,I stayed in the Darwin D Martin House by Frank Lloyd Wright To my mind Wright was the first Western architect whose work focused on space rather on the building as an object.

To move around inside Wright's houses is to understand his thinking about design Because he learned about architecture by experimenting with building his home and studio,he was able to establish a clear understanding of what is "real" and what is "conceptual" This is the fundamental difference between "being present" in a space - where you are absorbed with it - and looking at images of a space -where your mind is detached.

The Kimbell Museum by Louis Kahn is another example of a space where you feel each element contributes to a totality - the architecture,space,lighting,exhibits and even yourself within it It's like yin-yang: without yin,yang could not exist.

KG: In what other ways do you think architecture can enhance or influence human experience?

L: Space is perceived through a dialogue between imagination and reality It's like when a writer creates a story - they use their imagination to develop and re-interpret the reality of their own experiences.

Chinese literature clearly illustrates the importance of architecture in our lives and the relationship we have with it Chinese stories often situate their narratives within architectural settings and experiences in Chinese architecture can derive from literary texts In Chinese poetry,time and space are usually defined at the outset because without this concrete platform it is difficult for the text to communicate its message In Chinese literature,every story happens somewhere.

Chinese stories often attach a certain meaning to a particular space and this defines how a network of people can associate with each other - space determines and describes a social pattern In Chinese culture,it is important to be able to grasp one's position in space,time and society.The establishment of a structure of tangible spatial references facilitates this process It's,again,like the Forbidden City where you are led through five or six different gates in sequence before you arrive at the palace The length of each courtyard is different so the sequence builds a specific momentum.The thresholds themselves define varying levels of privacy,with regulations to govern how high a threshold can be or how many locks there are on a door,depending on the rank of the individual officer.

KG: The experience of visiting the Royal Academy of Arts has a similar sense of sequencing: moving from busy Piccadilly into the Annenberg courtyard,then entering the seventeenth-century town-palace,up the grand staircase and into the nineteenth-century Main Galleries How does your installation build upon this layering of space and thresholds?

L: This is already a rich sequence On the street you have a mix of different textures and noises,different people from different backgrounds Then in the galleries it's very pure.

Once you enter the installation itself,I'd like it to seem like a journey of discovery and for visitors to have the sense that alternative worlds run alongside their path and intersect with it Along the way,not everything will be visible and clear.Instead,the story unfolds like the painted image on a Chinese handscroll,something to be appreciated over time By the end,they will have gained a series of impressions that create a new mental landscape.

KG: Can you describe how you envisage the project in more detail?

L: Metaphorically,you are walking through a snowy forest at night - represented by a maze of slender branches or twigs with the white floor lit from below As you explore,you discover niches that provide hope and happy surprises At the end of the maze you arrive at a Zen garden which represents clearsightedness and inspiration From an epistemological point of view,this invites you to look and understand,to turn "blindness" into "vision".

I'm using branches because they are a natural material people don't expect to see in architecture And the unconventional application of a familiar material in an unexpected environment has a strong an effect When you want to be creative,it's often not about originality per se but rather about application and re-use In the countryside you might try to blend the branches with nature but in London it's about creating a seemingly natural setting within an artificial environment.

I have used a mirror in the Zen garden because mirrors have the power to change the feeling of a space It's no longer about the physical presence of a wall,but rather the illusion of something else The mirror makes the space seem expansive even though it is enclosed Mirrors are used a lot in feng shui,which is fundamentally about the environment and the flow of energy.

KG: You have spoken about creating a "pinch of consciousness" for the viewer by way of contrasting spatial conditions How do you hope to achieve this?

L: The core concept of the installation in terms of connection - or rather disconnection - to London is to pinch the consciousness by de-familiarisation.

Much of the effect will come from the changing atmosphere as you move through the space At first the texture,scale and dimensions are clearly defined and familiar yet there is a loss of orientation Then,in the Zen garden,you experience a new openness and sense of revelation This contrast and the flow of energy through the spaces invite you to speculate on your experience and heighten your awareness.

KG: In what ways has your approach to creating an installation for an exhibition differed from your usual practice?

L: In most architectural commissions there is a specified function and programme but with an exhibition it's more about aesthetic experience On the one hand it’s easier,because you don't have to think about practical issues.But on the other hand it’s more difficult because you need to create a space that people will find appealing - they expect something but they don't know what For me,the main question is how do you arouse their curiosity and generate the impact you want

英国皇家艺术学院德鲁·海因茨建筑馆馆长,“感知空间:建筑之再定义”展览(2014年1月25日-4月6日)策展人/Curator of "Sensing Spaces: Architecture Reimagined" (25 January-6 April,2014),Drue Heinz Curator of Architecture,Royal Academy of Arts

2014-07-15