走向综合

2013-10-23作者纳塔利格力罗

作者:纳塔利·格力罗

“DesignWorkshop(DW)LegacyDesign®对一种设计过程和道德标准进行了清楚的描述,既考虑周到,也合乎情理。在新兴的景观绩效设计时代,DW以绩效为基础的实践强调了景观建筑行业的价值。近年来,通过与学术机构和‘景观建筑基金会’的合作,DW对景观建筑教育和研究的影响与日俱增。”

–犹他州立大学景观建筑与环境规划部副教授杨波

“一套技能和价值体系往往会因困境受制于另一套系统。DWLegacyDesign®在不同的技能层面和价值系统上追寻广泛的可量化目标,并乐于接受合理设计途径的挑战。”

这些话语出自DesignWorkshop的首席设计官托德·约翰逊,指的是DesignWorkshop人为自己设定的任务之艰巨——在设计思路上开拓创新、与时俱进、面面俱到,在解决方案上则遵循多年实践经验所总结出来的设计原则。

实现这种自我强加的强制性任务的一个关键是,创造基于证据的设计——这样的设计围绕着可量化的目标,并建立在所获得数据的基础之上,而这样的设计又可以为公司不断扩展的知识库添砖加瓦。

遵循着“所测即所得”的格言,DesignWorkshop选择的研究方法之核心在于度量指标,这一核心使公司能够对照项目的预期目标来衡量其工作的效率、绩效、进度或质量。虽然众所周知的是,没有一个目标衡量清单可完全包含景观建筑的广度或范围,甚至仅仅囊括一个特定项目的复杂性和差异性都很困难,但是,DesignWorkshop仍然坚持在每一个项目中实行目标可量化的设计操作,进而形成设计核对清单,同时也提供设计探索的机会,如此可帮助各个项目团队确定项目目标并预估目标实现后将带来的效益。然而这样的绩效衡量策略只是帮助确定了项目的基本切入点,对于不同项目的最终设计成果而言,在进一步深化设计的过程中都将根据其独特的环境和特定的目标量身定制。对于某个给定的项目,设计证据和DWLegacyDesign®的真正力量取决于度量指标的透明度和相关性。这些度量指标必须与设计预想结果相关联,且同时也要与其它选定的度量指标相协调。

公司强调使用这种研究型方法论,早在此方法建立之初的2002年的公司备忘录里,库尔特·卡伯特森董事长就对其进行了最精辟的解释“这些度量指标可成为评估我们是否取得进步的常用词汇。”公司认为,循证方法——无论是否像Design

图1 (fig.1)CREDIT:D.A.Horchner/DesignWorkshopOne of Design Workshop’s signature projects, Daybreak, a 4,126-acre (1,670-hectare)new community just 25 miles (40 kilometers)from Utah’s capital, Salt Lake City, illustrates the value and power of incorporating a research-based methodology into design.DW的一个标志性项目,Daybreak,4126英亩(1670公顷)的新社区,离犹他州的首府盐湖城仅25英里(40公里),说明了将研究为基础的方法转化为设计的价值和力量。

Workshop一样以度量指标为中心——都是行业监控规划和建设的成功与不足的关键,也是行业从中学习的关键。(请参看图1)

四重盈余法

DWLegacyDesign®是DesignWorkshop综合型的循证研究和实践的方法论,主要基于四大范畴——景观建筑的传统因素(艺术与环境)与被视为具有同等价值的元素——社区与经济。在这四个范畴所设定的基础上,公司的设计理念为:

环境:人类的生存依赖于对自然体系价值的认知以及对自然体系保护活动的自发组织。设计应该与土地情况相契合,才能造福子孙后代并带来长期的价值。

经济:开发项目所需的资金流以及在项目使用年限内所能产生的收益界定了经济可行性。因此,设计理应提供一套可促进并保护区域的完整性的长期性经济机制。

社区:人与人之间的实体联系构成了家庭、群体、城镇、城市和国家的文化,是这其中每一个要素繁荣昌盛的基础。设计应该将这些社区组织起来以培养他们之间的各种联系并提升彼此间相互包容的能力。

艺术:美学有助于界定真实、独特的场所,赋予生命的意义,并对人文精神的回归产生积极影响。设计应该通过与艺术结合来激发灵感并鼓舞人心,进而提升经济价值,确保可行性并且吸引资金,从而有助于确保项目恒久长存。

DesignWorkshop始终相信,最引人入胜的场所是那些把环境、经济、社区与艺术融合在一起的地方(公司称之为四重盈余)。远在20世纪90年代末,公司正式定义了DWLegacyDesign®方法之前,团队成员早已将这些原则融合到项目工作中。公司对每一个范畴的深入剖析会逐渐显露在接下来的篇幅里,公司的标识性项目之一,位于犹他州SouthJordan的一个4126英亩(1670公顷)的大型新社区Daybreak,将会被作为案例进行讲述。

在这里强调Daybreak这个项目,事实上是要强调研究型方法论纳入设计工作的价值和力量。这里将叙述我们在这个项目中进行的各种努力,譬如保护和修复环境采用的特殊方法以及用于振兴社区经济的设计和美学。这些范例可以充分说明景观建筑及其相关学科在实践中的卓越与严谨所创造的成果能够符合当今世界的需求和目标,同时也可为未来世界保留发展机会。DesignWorkshop指出,如果度量指标的完成仅仅是单一的停留在某一个范畴中,那这样的测量方法对我们构建成功社区,提高我们的文化生活水平,维持长期的财政稳定性以及实现世界的可持续发展将毫无贡献。DesignWorkshop认为,其方法论的力量在于将这四大范畴整体性的融合到了一起。(请参看图2、图3)

环境

对于塑造建成环境的设计行业人士而言,环境被视为设计与规划过程的一部分,是第二自然。从帕特里克·戈德斯和伊恩·麦克哈格到安妮·惠斯顿·史必恩和查尔斯·瓦尔德海姆,那些在景观建筑领域的学术上和专业实践上的思想领袖们早已强调过设计需要从周边的自然环境中获得启示继而创造或再创造功能性自然体系。

不过,设计师并不是唯一意识到环境和人类之间的影响及依赖关系的人群。全球变暖和大气层的变化促使许多人——政治领袖、规划师、建筑师、经济学家、环境学家和普通大众——都意识到环境并非只是一些可持续发展与节能减排的措施。总体上来说,我们普遍相信,我们不能在使用地球资源的同时不施加足够的积极影响,否则,我们的子孙后代将无法享受与我们相同的生活质量。这里提到的地球资源,不仅包括不可再生资源(如:矿物燃料),也包括可再生资源(如:空气和水)。在当今世界,环境是我们共同的未来赖以生存的最主要关注对象。

DesignWorkshop对环境的影响以及对设计过程中目标的考虑,主要是基于以下想法:真正可衡量和有意义的设计方案在某种程度上必须主要建立在可重现的科学研究和数据上,当然也不排除某些部分会建立在实践经验的基础上。这意味着,建立一套度量指标去监控和模拟能源利用、建筑和景观绩效以及客户对某种形式的使用时长等等。这意味着不断比较和提炼这些因素,以便减轻景观、建筑、社区、城市甚至是国家对环境产生的影响并提升绩效。

术语“环境度量指标”意味着,测量和比较诸如空气质量、雨水质量及回收利用、能源、野生动物栖息地、噪音污染消减、开放空间的保护或创建以及其它许多定量因素对于一个项目的最终成功是必不可少的。不过,简而言之就是设定一条基线用来确立现状环境中哪些因素需要进行测量,而后获得的实质性数据则有助于为进一步的改进提升明确目标绩效。当这些度量指标典型性地呈现出定量而非定性的特征时,他们就为景观建筑和社区设计的可量化结果指明了内在需求,而这些可测量的结果表明我们对我们的行动与周围自然环境之间的因果关系的关注。

Daybreak社区距离犹他州首府盐湖城仅25英里(40千米),是经过细心规划的,不仅顾及到建设行为与自然环境之间的因果效应,同时也致力于为当代人和后代人创造一个拥有丰富水源和洁净空气的美丽的社区。该社区的开发商KennecottLand要求DesignWorkshop为其新社区提供公园和开放空间的系统框架。由于该社区所在的环境非常脆弱而且高度沙漠化,传统的水资源集约化开发和精心设计的地形在这里不仅不可持续而且难以让人满意。为了符合当地的雨水管理条例并适应周边环境基底,设计团队为Daybreak设计了的公园和开放空间不仅在视觉上令人赏心悦目,而且在环境上具有可持续性。

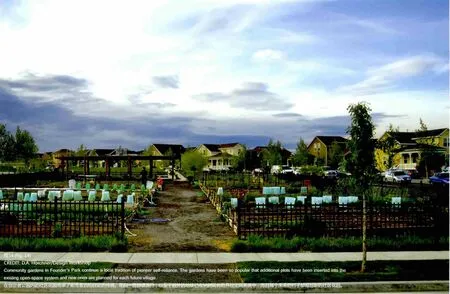

图2 、图3(fig.2andfig.3)CREDIT:D.A.Horchner/DesignWorkshopOnce the largest open-pit copper mine in the world, Daybreak is now the largest master-planned community in Utah and boasts an extensive trail system, recreational water features, active sports f elds, community vegetable gardens, performance space, and demonstration gardens of native plants.曾经是世界上最大的露天铜矿,Daybreak如今是犹他州最大的总体规划社区并拥有一个广泛的步道系统、娱乐性水景、活跃的运动场地、社区菜园、表演空间以及本地植物示范园。

水|在任何涉及到环境因素的设计中,水的利用必然是最重要的。水在我们的日常生活中是无处不在的。它是我们人类最为重要的需求:我们需要水来饮用、烹饪和清洁;我们也需要水来维持环境卫生和预防火灾。没有水我们无法生存。理所当然的,几乎每一个设计项目都需要面对雨洪管理、区域水资源利用、节约用水、水资源保护和废水处理技术等各类与水相关的问题。

如果用Daybreak社区的案例来详细阐述的话,该社区的公共景观设计展示了一套合理利用水资源创造优美、丰富的环境的有效且高效的方式,从而转变了利用大量水资源绿化沙漠的普遍范式。(请参看图4)

由于犹他州的SouthJordan年均降水量仅为18.18英寸(46.2厘米),因此,水在Daybreak是非常珍贵的。针对大暴雨情况,设计师通过设计一系列相互连接的生态排水沟、洼地和人工湿地如奥克尔湖(65英亩/26.3公顷,是社区的核心组织特征)形成的雨洪管理系统来收集、清洁和过滤所有落到现场土地上的雨水。该体系减少了与地表径流相关的污染,预防了下游洪灾的发生,且有助于补充当地的蓄水层。该设计实现了场地与市政雨洪管网系统连接设备的零需求。考虑到犹他州的大部分住宅社区都需要收集和过滤10年/24小时暴风雨产生的雨水,相较而言,Daybreak社区的系统可以说是非凡的。因为这意味着,如果遇到百年一遇的暴风雨,Daybreak社区所收集和过滤的径流量比犹他州其它大部分的社区会多出44%。连接到区域运河网的次级水系统可为整个开放空间和奥克尔湖提供满足灌溉需求的原水而无需利用市政的饮用水。(请参看图5)

值得注意的是,Daybreak的雨水基础设施带来的不仅仅是环境效益。据工程师估算,在Daybreak项目使用期限内省去的市政影响产生的费用,以及大量减少的水输送的传统基础设施费用,实际设计的雨洪基础设施节约了超过7千万美元(4.32亿人民币)。其中包括3千万美元(1.851亿人民币)的住宅影响费用的节省,业主住宅所有权的增加以及嵌入式基础设施的减少。此外,此基础设施由于创建了公园和集会空间而使社区获益匪浅,同时还由于并创建了优美的开放空间系统网络,增加了社区的美感。这些统计数据充分体现了DesignWorkshop设计理念一体化所产生的巨大力量。

除了高效的雨洪管理之外,Daybreak也因其节水率高而闻名。每个家庭使用的都是低流量装置、高科技灌溉系统,并栽种了本地耐旱植物,因此,与老居民区的同类家庭相比,Daybreak的家庭每个月平均节约了5206加仑水。截至2009年8月份,社区2106个家庭共节约了79,759,877加仑(3.019亿公升)水,平均每个家庭节约的水量超过41,000加仑(155,202公升)。

乡土植物和节水植物的栽种|对于给定景观而言,重新引进乡土植物或节水的植物有许多的益处。这些植物有助于满足本地野生动植物的需求(如:栖息地与食物),而不会对当地的植物群落造成长期的损害。它们有助于防止外来入侵植物进入到该区域中。此外,本地乡土植物通常生长得很好,需要的杀虫剂较少,且如上所述,需要的水分较少。(请参看图6)

DesignWorkshop通过选择乡土植物(包括北美三齿苦树(Purshiatridentate)、接骨木(Sambucus)和Rabbitbrush(Ericamerianauseosa)将Daybreak与其自然历史相接,这里的自然历史包括了延伸到山脉中的生态廊道和区域性的植被肌理。“首创者之村”作为社区内竣工的第一个村庄,其72%的公园和开放空间所用的都是乡土植物或节水植物(需要灌溉的草皮仅限于必要的活动场地)。

总而言之,把乡土植物和节水植物纳入景观是有益的,因为保存了大量的水资源(如上所述),从而为鱼类、小型哺乳类和那些每年都会经过大盐湖上候鸟通道的水禽类提供了栖息地。自社区的湖泊及其湿地建成后,犹他州奥杜邦协会就开始了对栖息地的鸟类的观察活动。迄今为止,湖泊中已记录并识别的鸟类已有100多种。

和采用乡土植物和节水植物所获得的效益一起,DesignWorkshop还从Daybreak吸取了一些重要的经验,并将这些经验纳入到了未来Daybreak村庄设计中甚至更多的近期项目中(如:LowryDevelopment——1848英亩[747.9公顷]大的科罗拉多州丹佛前美国空军基地,BlueHole区域公园——126英亩[51公顷]的德克萨斯州温布莱自然保护区)。DesignWorkshop团队发现,让业主和准买家在文化上接受乡土草本植物存在着很大的挑战,因为这些草本植物在开始成熟和自播繁衍之前会显现出杂草丛生的蓬乱感,而达到成熟和自播繁衍的过程通常需要好几个季节。此外,设计团队还得知,若利用更传统的、修剪整齐的景观作为乡土植物造景的框架,居民会更乐意接受并了解乡土植被覆盖的草地和种植区的意义。简单的将贴近道路旁边的一条2英尺的(0.6米)条状绿地设计为经常修剪的整齐的短草坪,将之后的绿地过度为大面积的乡土植被种植区,可以将乡土草地框出来并可强调构建草地的目的性,这样的方式更容易为越来越多的受众所理解。此外,设计团队还得知,相比在居民买房之后再栽种乡土植物,未来的业主更容易接受那些在出售土地或建筑家园之前就构建好的乡土植物景观。(请参看图7)

碳足迹|最近,人们花费很大的精力来减少项目开发的碳足迹。事实证明,大的碳足迹对环境具有有害的影响——包括诸如气候变化、资源耗竭以及温室气体排放的增加等。减少碳足迹最好的方法包括:减少消耗量、循环利用废弃物和回收利用旧材料。

DesignWorkshop通过减少机动车辆交通的需求而帮助Daybreak社区减少其碳足迹。通过设计布局的开放空间系统可以让每家每户在5分钟(或0.25英里/0.4千米)的步行范围内可达。然后这一系统包含的散步径、小路可连接到社区的各个主要的目的地(如:学校、教堂、村中心和轻轨站)。正因为这些居民区的可步行性,有88%的Daybreak学生都是步行去上学,而在周边那些相比下不那么容易步行的居民区内,这个数据只有17%。目前整个社区有22英里(35.4千米)长的散步径,开发商计划在未来的村庄里创建更多这样的路径。到目前为止,这些努力已经阻止了8505.6吨(770万千克)的碳进入大气层(这相当于抵消了177户美国标准家庭所产生的碳排放影响)。(请参看图8)

DesignWorkshop帮助Daybreak减少其碳足迹的另一个方法是循环和回收利用现有的材料。施工人员和承包商循环回收了四分之三以上的建筑垃圾。有43500吨(3950万千克)来自于邻近宾汉铜矿的废石被用于建设公园和开放空间系统的墙和石笼。石笼墙已成为Daybreak景观的一个标识性元素。这些石笼墙服务于多种不同的目的,贯穿在整个社区中,不仅将美学的价值牢牢地系在场地上还与宾汉铜矿形成了文化关联。

经济

如果资产负债表和基本经济原理是唯一的度量衡,那么,在市场经济方面取得成功则通常是显而易见的。例如,如果某项努力的预期结果是正向的(就是说即使是对于最务实投资者,数字的总和也是有利于投资商的),那么,盈余应等于净利润。经济测量是我们最熟悉的、最容易并得到过优良检验的指标体系。在房地产开发项目中,投资回报率(ROI)是一项普遍流行的绩效指标,原因在于其用途广泛性和简单性。ROI常用于评估某项投资的效益或比较多项不同投资的效益。如果一项投资无法产生正数的ROI,或者,如果还有其它的投资机会可以获得更高的ROI,那么,直觉上讲,这项投资不适宜被采取。

在项目开始之初,确定经济可行性和经济影响所需要的精度将决定对预期结果判断的准确度。这一程序一旦启动,批判性的问题将会被提出度量,指标——(即清晰、公认的标准以及构成“可靠证据”的指南)也将建立,于是成败可能都将被记录、被分享,然后要么成为设计基础,反过来,要么再也不会被重复。不过,对于许多公司而言,真正的成功与否不再以财政绩效为唯一的基线进行判定。目前的判断指标还包括社会和文化的衍生物、环境的影响以及生活质量指标。在景观建筑、设计和规划方面,这种四重盈余法是确定依据和测量点的关键。若每个范畴没有合适的指南,开发商和景观建筑师会在衡量各种结果并确定判断成败依据时承受巨大的压力。

在Daybreak社区所制定的指南以及测量出的结果充分体现了这种方法的有效性。开发商和区域的经济回报是丰厚的,与DesignWorkshop的所有项目一样,经济可行性与环境敏锐度、社区合作和审美特征相融合,巩固了这些积极的财政业绩。需要重申的是,证据的真正力量取决于度量指标的透明度及其相互融合的能力。

环境保护|越来越多的证据证明,在可持续发展方面所作的努力不仅仅有利于地球,也有利于人类自身和利润增长。对于某个开发项目,若节省或修复资源的价值超过消耗的资源的价值,就可以说这个该项目取得了财政上的成功。

Daybreak的情况就是这样。许多确立的可持续发展倡议都在社区取得的巨大的财政收益中做出了贡献。如前所述,利用地表雨洪管理系统来消除雨水影响产生的费用,并极大减少了地下管道、基础设施的建设和维护,据估算节约了7000万美元(4.32亿人民币)。另外,通过循环利用建筑垃圾和重复利用现场旧材料,社区已节约了160万美元(990万人民币)以上的混凝土费用和运输费用。

此外,由于在Daybreak建立的所有家园都必须通过能源之星®的认证,因此,业主平均每年在公共设施费用方面就已节约了400美元(2466人民币)。

投资回报率(ROI)|每个项目的目标ROI都会考虑到当地市场的性质、其它投资机会、项目的风险以及投资商的看法。开发商/投资商的目标是赚的比投的多。

Daybreak的公园和开放空间系统已为社区的土地所有者、业主和未来居住者创造了价值,并为开发商提供了巨大的ROI。2009年至今,依靠在设计、咨询和施工方面共计6730万美元(4.149亿人民币)的投入,Daybreak已然成为犹他州畅销的新家园;盐湖郡五分之一的新家园交易就集中在Daybreak。同样在2009年,在以总体规划为基础进行开发的社区中,Daybreak在全美最畅销社区榜单上排名第六。开发商提出的让所有家庭都紧挨着公园或开放空间的承诺已兑现:三分之一的家庭都面向开放空间,因而价格一直居高不下,转售价值比其它地点高出10%。(请参看图9)

就业|新社区开发的成功有一部分取决于创造了多少就业机会以及开发为区域带来了多少收入。

Daybreak全面建成后,计划会新增2万个就业机会。区域轻轨系统刚刚延伸到Daybreak已规划的城镇中心,第一批商业建筑的开发也即将全部竣工(如:刚竣工的SouthJordan医疗中心配有24小时急诊室、初级护理设施和专科诊所,力拓集团区域中心[其下属企业肯尼科特犹他铜矿公司是犹他州最大的私营经济动因]以及在SoDaRow的许多小型零售企业)。城镇中心最终会成为各类企业的总部办公区、区域性全方位服务的医疗中心、区域性零售终端、都市住宅区、托管公寓和普通公寓集中区,甚至还有可能会成为大学校园的所在地。Daybreak的设计和布局已经把这些实体也纳入了社区,将为区域创造大量就业机会。

社区

现代的分散型美国城市(住所与工作地点在地理上的距离很远)使所有国民都依赖于自动化。社区分裂、社会交往被剥夺、身体健康状况下降、对城市核心部分的公共投资不足,导致传统的市中心完全废弃和停业。

为了克服这种关联性和实体上的分裂障碍,规划师、设计师和开发商目前正在通过鼓励体育活动、推行可持续设计以及建设以各种散步径、开放空间和集会区连接的公共场地和社区,来创造一种可以鼓励新的生活质量的场所。把这些元素设计到新社区规划的方案中,可以在提升社区定位以及改善人与人之间的互动方式方面起到重大的作用,继而促使一些不良因素如公众健康状况下降、城市无计划延伸、居民区以汽车为中心且依赖于汽车以及环境退化等转向良性方向发展。

Daybreak的城市街道适宜步行并可使居民区与公园用地之间相关联,而事实证明,城市街道景观可对居民健康产生积极的影响。日常活动量增加,可以减少肥胖的风险,也可以减少由于缺乏锻炼而导致的疾病的发病率。此外,居民区的绿色空间可以减少犯罪,增加社区的安全感,还有可能创建一个更具社会可持续性、更有凝聚力的社区,从而提升社会资本和公民参与度。从全球来看,城市绿色空间可通过改善空气质量、保护流域和连接野生动物栖息地来保护自然生态系统的功能。树木覆盖率、屋顶花园和乡土植被的增加,有助于降低城市热岛效应,从而减少能源需求和燃料消耗,否则,燃料的消耗增加会产生更多温室气体。增加的植被也可作为碳汇,用于减少二氧化碳的含量。绿色街道使人们不再开汽车出行,而选择步行和骑自行车作为交通方式。(请参看图10)

绩效衡量与社区的身心改善有着直接的联系,可与环境标准、经济标准和审美标准互换。从Daybreak社区衍生出的例子可以证实,绩效衡量在于内心是否有愿望为人们提供互动的场所和机会。这是通过观察社区与多重人际关系网的结合方式、设计提升人际关系网和社区各个场所交叉点的方法以及人与人的互动方式和人与空间环境的互动方式而实现的。

可步行|为了抵制社区对汽车的依赖性,开发商和设计师目前正努力地建造适宜步行并提倡步行方式的场所。适宜步行的居民区提供的效益,远远不只是减少车辆排放量所产生的环境效益这么简单。事实证明,适宜步行的居民区可以促进居民的身体健康,增进邻里之间的社会互动。(请参看图11)

先前已指出,Daybreak社区的可步行居民区(公共设施距离每家每户仅0.25英里/0.4千米的行程)已具有显著的环境优势,而其带来的社区的社会福利也同样不容忽视。Daybreak的可步行设计鼓励面对面的互动,让居民相互联系;此外,大量的散步径系统连接了居民区、学校、教堂、社区中心和奥克尔湖周边区域。据报告,2010年,Daybreak有88%的学生都是步行去上学,而周围不大适宜步行的居民区这个数据只为17%。虽然目前无数据证明健康情况的改善都归功于Daybreak的可步行居民区,但是,人们普遍认为,如果整个公共廊道系统(而不仅仅是某些专用的路径)都是可步行的(对于Daybreak社区,这当然是确切无疑的),则可步行为健康所带来的益处就可得到最佳的保证。由于这种开发在未来的几年内才成熟,因此,DesignWorkshop希望拥有更多的实质性记录资料和可计量证据,以支持Daybreak的可步行设计所带来的相对应的健康效应。

开放空间|城市开放空间提供的价值是实质性的。从生态学的角度看,开放空间可为环境中那些因城市开发而无法生存下去的自然物种提供家园。从美学的角度看,益处是显而易见的——开放空间为本应是灰色的城市景观提供美和舒缓。从娱乐的角度看,开放空间可以为各种宜动和宜静的活动提供场所,并促进邻里之间的交流互动。(请参看图12、图13)

公共景观构成了Daybreak的社会和文化体系的支柱。在所有开发的4100英亩(1659公顷)土地上,被规划为公园和开放空间的面积达到1000英亩(404.7公顷)。该系统的每一个元素,包括22英里(35.4千米)以上的被动步道、娱乐喷泉水景、各活跃的体育活动、表演空间和原生态示范园林,都是为了在社区生活中起到特定的作用而经过精心设计和策划的,其规模和位置都恰当地服务于Daybreak各个村庄的特定的人口统计数据。如前所述,开放空间系统是为了让各个地方相互连接,旨在促进步行,并改善雨水输送路径。这种设计理念充分体现了DesignWorkshop一体化方法的有效性。

社区花园|把社区花园和城市农场整合到社区规划中,在美国正在逐渐流行。这样的规划可以吸引居民、扶持当地农场、促进经济发展、创造邻里/大社区交往互动的机会,并为各个年龄层的人提供受教育机会。(请参看图14)

图4 (fig.4)CREDIT:D.A.Horchner/DesignWorkshopAcanallinedwithpoplarwindrowsrecallstheculturallandscapeofMormonpioneersandcreatesapopularwadingarea.Thecanalcarriesstormandlake-outfallwaterandleadstoaseriesofconstructedwetlandsthataerateandremovetoxinsfromthewater.两旁排列着白杨树的人工水渠使人想起摩门教拓荒者的文化景观,并创造了一个受欢迎的浅水区。水渠将洪水和湖泊排出水引向一系列的可以净化水质的人工湿地。

Daybreak现有的开放空间系统总共有六个社区花园,包含250多块园地,可为目前3%左右的人口提供社区花园。这些花园承载着山谷或美国西部自给自足的传统,教导居民在GreatBasin生态区内如何负责地建造景观,事实证明,这些花园是如此的成功以至于开发商都被此激励而计划增加一些花园到那些原本没有规划社区花园的开放空间中去。未来的目标是提供足够的社区花园以实现为社区10%的人口的自给。

艺术

最后一个Legacy范畴——艺术,可能是最难以衡量和量化的一个,因此,也是最难建立有效指标的一个。当艺术融入到景观建筑设计中时,它的成功与否甚至变得更加复杂并且更加难以衡量。毕竟,一个人该如何去解释一些东西是精巧的还是粗线条的,是公共的还是私人的,是因其声明被而排斥的还是因其吸引力而被崇拜的,是被批判的还是被颂扬的,是冗余的还是精炼的,是短暂的还是永恒的?还有,到底该如何去衡量一个对主观性和个人看法如此开放的事物呢?

任何关于如何“衡量”艺术或美学影响的讨论都要从揭示定义开始。在这里的讨论中,艺术被定义为空间吸引力——也就是那些可以为环境增加艺术价值的事物,它可以是公共场所、街道角落或是建筑立面。美学定义了一个事物的模样。它是一种描述美和感受的方法。这两者都包含了一定程度的主观性;不过,评价艺术或美感的行为对项目是至关重要的,因为这种行为可以确立一系列观点的范围,构建出可解决基本问题(如:意义、持久性、创新性和可靠性)的框架。DWLegacyDesign®认为,有两种方法论可运用于艺术衡量:定量法和定性法。定量指标是可计数的:项目包含的艺术作品的数量、包含的艺术博物馆、表演艺术中心或策划在项目里的公共艺术;是否有视觉艺术家参与合作过程,或者在设计中公开表演所用的场地是怎样的。公众对这些问题的反应对衡量结果是至关重要的。公众是否参与公共艺术过程,或是否应邀对现有景观的视觉质量进行评价,或是否应邀对拟定设计的质量作出评论?是否有一种合适的条件评估方法论,看看公众是否乐意为公共艺术埋单并接受因景观增加社区福利而带来的责任?公共艺术是否为社区提供机会去讨论艺术途径和并决定表达对艺术价值看法的集体观点?定性指标更模糊一些,认为“好”的艺术(被主观定义为美丽、具有魅力或满足公共需求)就可以吸引类似的元素。这些指标虽然无法确保最终结果的一致性,但确实更有可能使成功的美学因素或审美特征成为最终结果的一部分。(请参看图15)

当用于实现某个特定效果时,由于依附在一些具有特性和特征的东西上,艺术,无论以何种形式出现,便成为了可以衡量的元素。而空间创造固有的智慧和情感内涵(包括创作理念、空间布局和运用的材料)便成为了展示窗口。测量方法可以适用于创作理念汇聚的方式上,包括应用美学和艺术本身固有的叙事性以及与艺术互动的社区健康度和人类安全感。如果艺术是通过提升社区文化和周围环境的稳定性而成功地成为焦点,那么,艺术很有可能已在目的上获得成功。存在于街道景观的艺术作品的数量或者新社区内是否有表演艺术中心无疑是非常重要的,但是,比这一点更加重要的是艺术的质量可靠性。无论艺术采取何种形式,只要具备其重要性和独特性,那么,艺术就已经达到了特定的效果,而且是可衡量的。

Daybreak社区的艺术指的是社区结构及其天然的美感。要获得定量的证据证明这些元素的价值是极具挑战性的;不过,从之前提到的Daybreak在经济、环境和社区方面取得的成功可以感知到这些美学价值存在的证据。需要重申的是,这四个Legacy范畴之间存在显而易见的关联性,在其中任何一个范畴中达成的目标会对其他一个甚至所有范畴中的元素产生影响。

地域特异性|DesignWorkshop认为,在规划和设计时把场地的地域特征考虑在内,将有助于把项目及其周围的环境联系起来。把区域特异性作为设计策略,要求对工作中所涉及的文化、环境和经济体系有着透彻的理解。此外,这一设计策略也有助于把项目与其它地域的项目和经验区分出来,使居民和访客能够深刻感受到他们与项目所在的场地和地域,以及当地居民的联系。这种场所感和认同感能够渗透到大到社区的区域或定义一个小到村庄或花园的区域。

对于Daybreak社区来说,设计意图是使其景观扎根于地域特征,并创建新的、可靠的、前瞻性的落基山脉景观,在承认过去的同时也可以应对当今的环境挑战并拥抱全新的美学形式。这些景观以是对其自然和文化环境的一种有意识的艺术化表达。创新的几何地形和磨旧的石笼墙是利用宾汉铜矿的回收废石建成的,这一创新性设计表达了场地与区域遗产的联系。这样的地形让人联想到铜矿中废石料形成几何形斜坡,这一景观成为了社区的背景帘幕,不过经过了乡土观赏草和植物群落的柔化得以舒缓。既然社区属于人工建筑物,则无需试图让开放空间看起来“自然”或看起来像未损坏的自然。恰恰相反,项目的人工特性是有意识的透过种有节水植物的几何形式而呈现的——自然与文化、环境与社区相融合,产生了一种新的美感,扎根于社区的环境背景和文化背景。与简单的废弃相反,整个景观重新利用的回收废石超过4.35万吨(3950万千克),在社区背后的山坡可以清楚的看到,这一设计策略加强了社区景观和铜矿在颜色、肌理和地形上的联系。乡土植物(包括北美三齿苦树、接骨木和Rabitbrush)把社区及其自然历史联系在一起,创造了一直延伸到山脉的生态廊道,重现了地域的原生植被模式。(请参看图16)

HillsidePark展示了自然山麓和当地河流的雕刻景观抽象概念。作为新建的奥克尔湖的排水口和曝气渠,水运河可把水输送到下游的人工湿地中。沿着运河的白杨让人回想起早期摩门教拓荒者沿灌溉水渠种植的标志性树种,而西方的作家华莱士·斯特格纳则称其为“摩门教景观”。河岸的廊道为野生动植物提供栖息地,成为了一条繁茂的杨木长廊。水道也作为雨水输送系统而通向渗滤池,可以将百年一遇的雨洪100%渗透到地下。

面向综合发展

如前所述,DesignWorkshop相信,最引人入胜的的场所是那些把环境、经济、社区与艺术融合在一起的地方。与之相关的是,公司的最高追求之一是证实这种信念的价值,并旨在通过绩效型研究方法论来实现。这种方法论使得公司能够对照项目的预期目标而衡量其工作的进度、执行力和质量。指标的透明度和相关性与预期结果有关,同时也致力于与其它选定目标一起综合发展。

全面研究DesignWorkshop如何将其绩效型方法论应用于犹他州SouthJordan的Daybreak社区的公园和开放空间系统,可以充分体现这种方法对该区域以及对公司自身的影响。这个项目的叙述可以为以下概念提供范例:景观建筑实践中的质量、严谨和责任性带来的业绩能够满足当今世界的需求和目标,同时也可为未来保留发展的机会。

无论是否如DesignWorkshop一样以度量指标为核心,循证方法都是分析景观规划和建设工作的成败以及从中吸取经验的关键。采用这种方法的个人和公司都会发现,这种方法对其自身、项目甚至整个行业都极具价值并大有裨益。

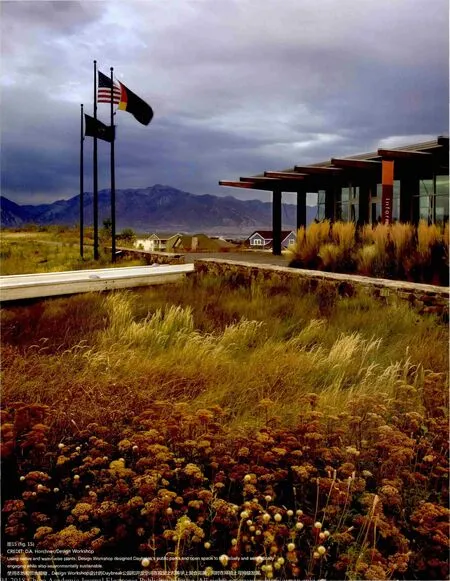

图5 (fig.5)CREDIT:D.A.Horchner/DesignWorkshopA stormwater inf ltration basin f lled with native grasses at the Daybreak Information Center celebrates the on-surface stormwater management infrastructure of the community. Walls created from recycled stone from Bingham Mine express the local mining heritage.在Daybreak信息中心长满本地牧草的雨水渗透洼地强调并展示社区的表面雨水管理设施。从宾厄姆矿回收石材砌成的墙壁表达了当地的矿业遗产。

纳塔利·格里洛在写作、编辑和公共关系方面拥有超过10年的经验。毕业于泰莱大学,在非营利性传讯与公共关系领域开始其职业生涯,致力于制定、提炼和简化各种营销与通信计划的附属计划。2005年进入DesignWorkshop工作,并在2013年前同时兼任许多项目的策划与推广。现在,纳塔利是一名自由作家,擅长与顾客或针对某个项目进行清晰、直接和恰当的沟通。

“The trap is always to enslave one set of skills and values to the other . DW Legacy Design®embraces broad and measurable goals across dif fering skill sets and value systems, and it takes on the challenge of a rational approach to design.”

Those words, from Design Workshop Chief Design Off cer Todd Johnson, speak to the enormity of the task those at Design Workshop have set out for themselves – to provide innovative, ever-evolving, all-inclusive design thinking and solutions that emerge from principles which have developed from years of practice.

A key to fulf lling this self-imposed mandate is to create designs that are evidence-based– design built around measurable targets and built upon acquired data that inform the f rm’s continually increasing knowledge base.

Following the maxim “what gets measured gets done,” Design W orkshop’s chosen research methodology is centered on metrics, enabling the firm to measure the efficiency, performance, progress, or quality of its work against a project’s intended goals. While fully cognizant that no list of measurement topics could wholly encompass the wide breadth and scope of all that is landscape architecture or even of the complexities and variances of just one specific project, Design W orkshop employs its metrics-based process on every project as both a checklist and an opportunity for discovery to help teams determine project goals and envision the benefits those accomplished goals will bring.iThese performance measures provide a baseline from which to start, but the outcome of each project is tailored to its unique circumstances

and objectives. On a given project, the real power of evidence and DW Legacy Design®relies on the transparency and the relevance of the metrics. They must be related to desired outcomes while also working in concert with the other chosen metrics.

The firm’s decision to focus on this research-based methodology is most concisely explained by Chairman Kurt Culbertson’s words in an early 2002 firm memo as this process was being established, “These metrics can become a common vocabulary against which to evaluate our progress.”iiThe firm believes that an evidence-based approach – whether centered around metrics like Design W orkshop’s or not – is the profession’s key both to monitoring success and shortfalls in planning and built work and to learning from them. (see f g. 1)

The Quadruple Bottom Line Approach

DW Legacy Design®is Design W orkshop’s comprehensive, evidence-based research and practice methodology based on four categories – the traditional elements of landscape architecture (art and environment)combined with what it believes are components of equal value: community and economics. The f rm’s philosophy of design in the context of these categories is:

Environment: Human existence depends on recognizing the value of natural systems and organizing its own activities to protect them. Design should fit purpose to the conditions of the land in ways that support future generations and drive value for the long term.

Economics: The flow of capital that is required to develop a project and the capital generated over its life de f nes economic viability. Design should seek to create longterm economic mechanisms that promote and protect the integrity of a place.

Community: Physical connections between people create the cultures of families,groups, towns, cities, and nations and are the foundation upon which they prosper .Design should organize these communities in order to nurture relationships and promote mutual tolerance.

Art: Aesthetics help def ne the real, distinct places that bring meaning to life and act as a restorative inf uence on the human spirit. Design should incorporate art to inspire and rejuvenate, boost economic value, support viability, and attract capital, thereby helping to ensure a project's longevity.

Design Workshop has always believed that the most compelling places are those where environment, economics, community, and art intersect. (The f rm refers to this as the quadruple-bottom-line.iii)Long before the f rm off cially def ned its DW Legacy Design®process in the late 1990s, team members were infusing these principles into project work. In the pages that follow, deeper explanations of the f rm’s perspective on each category will emerge, as will examples and the narrative about its process from one of its signature projects, Daybreak, a 4,126-acre (1,670-hectare)new community in South Jordan, Utah.

The story of Daybreak, highlighted here, speaks to the value and power of incorporating a research-based methodology into design work. This narrative describes ef forts such as exceptional methods employed for protecting and restoring the environment and the use of design and aesthetics to reinvigorate a community’s economy. These are good examples to advance the notion that excellence and rigor in the practice of landscape architecture and related disciplines can produce results that meet the needs and goals of today while preserving opportunities for tomorrow. Design Workshop notes that measurement in any of these categories contributes little to the success of our communities, our cultural life, and the f nancial and long-term stability and sustainability of our world if the metrics employed are completed in a vacuum. Design W orkshop believes the power of its methodology is due to its holistic fusion of all four categories.(see f g. 2 and f g. 3)

Environment

Regarding the environment as part of the design and planning process should be second nature to those in the design professions who shape the built environment. From Patrick Geddes and Ian McHarg to Anne Whiston Spirn and Charles Waldheim, leading thinkers in academic and professional landscape architecture practice have emphasized the need for design to take its cue from the surrounding natural environment and either create – or re-create – functional natural systems.

However it is more than just designers who are aware of the environment and humanity’s impact and dependence on it. Global warming and atmospheric changes have caused many people – political leaders, planners, architects, economists,environmentalists, and the general public – to think about the environment as more than just measures of sustainability, energy eff ciency, and emissions. Collectively, we now widely believe that we cannot use the earth’s natural resources without, at the same time, creating impacts on the ability of future generations to enjoy a quality of life equal to ours. This is true not only for non-renewable resources such as fossil fuels but also for renewable resources like air and water. In today’s world, environment is the primary concern upon which our collective future depends.

Design Workshop’s consideration of environmental impacts and goals in its design process is grounded in the idea that design solutions, to be truly measurable and meaningful, must be based, in part, on empirical, replicable scientific research and data. This means establishing metrics to monitor and model such things as energy use, building and landscape performance, and client use patterns over time. It means continually comparing and refining these factors so that landscapes, buildings,communities, cities, and even countries can lessen their impact on the environment and improve performance.

The term “environmental metrics” implies that measuring and comparing issues of air quality, stormwater quality and re-use, energy, wildlife habitat, noise pollution reduction,open space preservation or creation and many other quantitative elements are essential to the ultimate success of a project. Simply stated, however, a baseline establishes the existing condition of what is being measured and substantial data helps to identify a target performance for improvement. And while the metrics are typically quantitative rather than qualitative, they point to the inherent need in landscape architecture and community design for measurable results that indicate an awareness of the cause and effect of our actions on our surrounding natural environment.

The Daybreak Community, located just 25 miles (40 kilometers)from Utah’s capital, Salt Lake City, was carefully planned with both recognition of the cause-ef fect nature of our actions as well as with the intent to enrich present and future generations with a beautiful community, plentiful water, and clean air. The community’s developer, Kennecott Land,charged Design Workshop to create a framework of parks and open space for its new community, which is situated in a fragile, high-desert environment where conventional,water-intensive development and manicured terrains are neither sustainable nor desired. To meet local stormwater regulations and fit into the environmental context,the team designed Daybreak’s public parks and open space to be visually engaging yet environmentally sustainable.

Water | In any design discussion that incorporates environmental considerations, water use must be paramount. W ater is a constant in our everyday lives. It is the singlemost important human need we have: we need it to drink, cook and clean; we need it for sanitation and f re protection. We need it to live. And, as such, issues including stormwater management, regional water use, water use reduction, water conservation and/or wastewater technologies surround nearly every project.

Specifically with the Daybreak Community, the public landscapes were designed to shift the prevailing paradigm of greening the desert with extensive water use by demonstrating effective and eff cient ways to create beautiful and rich environments with responsible water use. (see f g. 4)

Since South Jordan’s average annual precipitation is just 18.18 inches (46.2 centimeters), water is a precious commodity at Daybreak.ivDesigners created a system that captures, cleans and infiltrates 100 percent of stormwater that falls on the site into the ground through a series of connected bio-swales, basins, and constructed wetlands including Oquirrh Lake (a 65-acre/26.3-hectare lake that is the community’s central organizing feature)during large storm events. The system reduces runof frelated pollution, prevents downstream f ooding, and helps to recharge the local aquifer.The design eliminates the need for any connections to the city’s municipal stormwater system. This is remarkable considering that most residential communities in Utah require the stormwater capture and in f ltration of a 10-year/24-hour storm. This means that in a 100-year storm event, the Daybreak Community is capturing and in f ltrating 44 percent more runoff than most other Utah communities. A secondary water system,connected to the regional canal network, supplies the entire open-space system and Oquirrh Lake with raw water for irrigation needs rather than using the municipality’s potable water. (see f g. 5)

It is worth noting that the benefits of Daybreak’s stormwater infrastructure alone are more than merely environmental. Engineers estimate over $70 million ($432 million Renminbi [RMB])in stormwater infrastructure savings over the life of the Daybreak project due to the elimination of municipal impact fees and the dramatic reduction in conventional conveyance infrastructure. This estimate includes $30 million ($185.1 RMB)in residential impact fees, residential entitlements by owner, and reduced inground infrastructure. Additionally, this infrastructure offers community benef t because it creates parks and gathering spaces as well as an aesthetic benef t because it creates a beautiful network of open spaces. These statistics illustrate the power of the integrated nature of Design Workshop’s design philosophy.

In addition to ef ficient stormwater management, Daybreak boasts of high water conservation rates. By using low-flow fixtures in each home, high-tech irrigation systems, and the installation of native drought-tolerant plants, Daybreak homes save an average of 5,206 gallons of water each month when measured against comparable homes in older neighborhoods.vAs of August 2009, the community’s 2,106 homes had saved over 41,000 gallons (155,202 liters)of water per home for a total of 79,759,877 gallons (301.9 million liters)saved.vi

Native and Water-wise Planting | The benef ts of re-introducing native or water-wise plants to a given landscape are many. These plants can help meet the needs of native wildlife (such as habitat and food)without causing long-term damage to local plant communities. They help prevent the introduction of invasive, exotic plants into a region.And, native plants generally grow well, require fewer pesticides, and – as mentioned above – need less water.vii(see f g. 6 )

Design Workshop chose native plants including bitterbrush (Purshia tridentate),elderberry (Sambucus), and rabbitbrush (Ericameria nauseosa)to connect Daybreak to its natural history, including wildlife corridors that run to the mountains and vegetative patterns of the area. With Founders V illage, the first village completed within the community, 72 percent of the parks and open space system is native or water-wise plant material. (Irrigated turf was limited to required active play f elds.)

Overall the incorporation of native and water-wise plants into the landscape has been beneficial in that it has conserved large volumes of water, as explained above, and has provided habitat for fish, small mammals, and waterfowl that annually traverse the Great Salt Lake migratory bird f yaway. The Audubon Society of Utah has been watching bird species since the construction of the lake and its wetlands. To date, they have documented and identif ed over 100 species of birds at the lake.

Along with the benef ts of using native and water-wise plants, Design Workshop learned a few important lessons at Daybreak that it has since incorporated into the design of future Daybreak villages as well as into more recent projects (Lowry Development, a 1,848-acre [747.9-hectare]former U.S. Air Force Base in Denver, Colorado and Blue Hole Regional Park, a 126-acre [51-hectare]nature preserve in Wimberley, Texas). The Design Workshop team found cultural acceptance of native grasses by homeowners and prospective buyers to be challenging because the grasses can appear to be weedy and unkempt until the meadows begin to mature and re-seed themselves, a process which typically takes several seasons. In addition, the design team learned that residents accept and understand the intent of the native meadows and plantings much more readily when the native landscape is framed with a more traditional, manicured landscape. A simple two-foot (0.6-meter)lawn swath next to a path that transitioned into large tracts of native planting frames the meadow and signif es the intentional nature of the meadow creation and is understood by a much wider audience. In addition, the design team learned that if a more native landscape was installed prior to the selling of lots or building of homes, the future homeowners were more able to accept it than if planting were installed after a resident bought a home. (see f g. 7)

Carbon Footprint | Much has been made of late regarding reducing development’s carbon footprint. It has been proven that large carbon footprints have harmful ef fects on the environment – including climate change, the depletion of resources, and increased greenhouse gas emissions. The best methods of reducing carbon footprints include reducing consumption, recycling waste, and reusing materials.viii

Design Workshop helped the Daybreak Community reduce its carbon footprint by decreasing the need for motorized transportation. The open space system was designed to be located within a five-minute (or 0.25-mile/0.4-kilometer)walk from every home. The system then contains trails, pathways, and links to all major community destinations such as schools, churches, village centers, and light-rail stations. These walkable neighborhoods have caused 88 percent of Daybreak students to walk to school, compared to 17 percent in surrounding, less-walkable neighborhoods.ixThere are 22 miles (35.4 kilometers)of trails throughout the community, and the developers have plans to create many more in future villages.These efforts have so far kept a total of 8,505.6 tons (7.7 million kilograms)of carbon from entering the atmosphere (which is akin to saving what would have been the impact of 177 standard U.S. households).x(see f g. 8)

Another way Design Workshop helped Daybreak reduce its carbon footprint is through recycling and reuse of existing materials. Builders and contractors recycled more than three fourths of their construction waste. And 43,500 tons (39.5 million kilograms)of waste rock from the adjacent Bingham Copper Mine has been utilized in walls and gabion baskets within the parks and open space system. The gabion walls have become an iconic element in the Daybreak landscape. They are used throughout the community for many dif ferent purposes and help tie the aesthetic to the site and its connection to the Bingham Copper Mine.

Economics

Evidence of economic success in the marketplace is typically obvious if balance sheets and basic economic principles are the sole points of measurement. For example, if the expected outcome of an endeavor is positive (meaning that the numbers add up to favor even the most pragmatic of investors), then the bottom line should equal a net prof t. Economic measurement is our most familiar and well-tested system of metrics. In real estate development projects, Return on investment (ROI)is a popular performance measure because of its versatility and simplicity. It is used to evaluate the ef f ciency of an investment or to compare the ef f ciency of a number of dif ferent investments. If an investment does not have a positive ROI, or if there are other opportunities with a higher ROI, then intuitively, the investment should not be undertaken.

The precision needed to establish economic feasibility and impact starts at the beginning of a project with the determination of an intended result. Once this is in place, the critical questions are developed and the metrics – clear and accepted standards and guidelines for what constitutes “credible evidence” – are established so that successes and failures may be documented, shared, and either built upon or, conversely, not repeated.However, for many companies, true success is no longer measured by focusing on the bottom line of f nancial performance alone. It now also includes measuring social and cultural ramif cations, environmental impacts, and quality of life indicators. In landscape architecture, design, and planning, this quadruple-bottom-line approach is the key to establishing evidence and points for measurement. Without guidelines in place for each of these categories, developers and landscape architects are hard-pressed to measure outcomes and establish proof of success or failure.

The guidelines established and the outcomes measured at the Daybreak Community illustrate the effectiveness of this approach. The financial returns to the developer and the region have been profound and, as with all Design W orkshop projects, these positive financial results were strengthened by the fusion of economic viability with environmental acuity, community collaboration, and aesthetic identity. Once again,the real power of evidence relies on the transparency of the metrics and their ability to coincide with one another.

Environmental Conservation | Increasingly, sustainability efforts are proving to benef t more than just the planet, but people and prof ts as well. And, for a development project,when the value of resources conserved or restored exceeds the value of the resources expended, the project is a f nancial success.

Such is the case for Daybreak. Many established sustainability initiatives have contributed to the enormous financial success of the community. As previously mentioned, the use of on-surface stormwater management systems eliminated stormwater impact fees and greatly reduced underground piping, infrastructure and maintenance, saving an estimated $70 million ($432 million RMB). Also, over $1.6 million ($9.9 million RMB)in concrete and transportation costs have been saved by recycling construction waste and reusing materials onsite.

In addition, as all homes built at Daybreak are required to be Energy Star®-rated,homeowners are already saving an average of up to $400 ($2,466 RMB)on utility costs annually.xi

Return on Investment (ROI)| The target ROI for each project takes into consideration the nature of the local market, other investment opportunities, the risk in the project, and the attitude of the investor(s). The goal is for the developers/investors to make more money than they invested.

Daybreak’s parks and open-space system has created value in the community for the land owner, homeowners, and future tenants and has provided enormous ROI to the developer. With $67.3 million ($414.9 million RMB)spent to date for design,consultation, and construction costs, Daybreak has been the top-selling new home community in Utah since 2009; one in five new homes sold in Salt Lake County is located in Daybreak. Also in 2009, Daybreak was ranked as the sixth best-selling master-planned community in the entire United States. The developer’s commitment to have all homes close to parks or open space has paid off: one-third of all homes face open space and thereby command premium prices and resale values of greater than 10 percent over other locations.xii(see f g. 9)

Employment | Part of the success of any new community development is how many jobs and how much revenue the development brings to a region.

Daybreak has been planned to create 20,000 new jobs by full build-out. The regional light rail system has just been extended into Daybreak’s planned town center and development of the f rst commercial buildings (such as the new South Jordan Medical Center complete with 24-hour emergency room, primary care facilities and medical off ces, Rio Tinto Regional Center [Headquarters to Kennecott Utah Copper – Utah’s largest private economic driver], and many small retailers at SoDa Row)are just being

completed. The Town Center will eventually be home to corporate of f ce headquarters,a regional full-service hospital, regional retail destinations, urban townhomes,condominiums and apartments, and perhaps, a university campus. Daybreak’s design and layout has drawn these entities into the community and will bring numerous jobs to the region.

Community

The modern and decentralized American city – where housing is geographically separated from the workplace by great distances – created an entire nation reliant upon the automobile. Communities were fractured, social interaction was curtailed, physical health declined, and lack of public investment in central parts of cities resulted in a complete abandonment and cessation of the traditional city center.

To overcome this relational and physical breakdown, planners, designers, and developers are now creating places that encourage a dif ferent quality of life through physical activity; sustainable design; and the creation of public spaces and communities connected by trails, open space, and gathering areas. Designing these elements into new community plans can play a signif cant role in elevating the positions of community and the ways in which people interact with one another – thus reversing declines in public health, urban sprawl, auto-centric and auto-dependent neighborhoods, and environmental degradation.

Urban streetscapes – designed here to be pedestrian friendly and to create connections between residential neighborhoods and parklands – have proven to generate positive health impacts on residents. An increase in daily activity levels brings about decreases in obesity and the onset of diseases related to inactivity. In addition, neighborhood green space reduces crime and increases the sense of safety in a community. It also creates the potential for a more socially sustainable, cohesive community that can improve social capital and civic engagement. On a global level, urban green spaces help conserve natural ecosystem functions by improving air quality, protecting watersheds,and connecting wildlife habitats. The increases in tree cover, green roofs, and native vegetation can help reduce urban heat island ef fect, thereby reducing energy demands and fuels consumption which, in turn, creates greenhouse gasses. Added vegetation also acts as a carbon sink, reducing carbon dioxide levels. Green streets get people out of their cars and out on their feet and bicycles. (see f g. 10)

Performance-based measurements that relate directly to the improvement of the community, both physically and spiritually, are interchangeable with environmental,economic, and aesthetic standards. And, as evidenced by the examples that follow from the Daybreak Community, measurement lies at the heart of a desire to provide locations and opportunities for people to interact. This is accomplished by observing the ways in which a community integrates its multiple human networks, the methods in which design elevates these networks and intersections at places in the community, and the means by which people interact with one another and their environment in these spaces.

Walkability | To combat a community’s reliance on the automobile, developers and designers now strive to create locations that embrace and celebrate pedestrian mobility.Walkable neighborhoods provide so much more than the environmental benefit of reducing vehicle emissions. They have been proven to advance the physical health of residents and to increase social interaction among neighbors. (see f g. 11)

While it has already been noted that the Daybreak Community’s walkable neighborhoods (where amenities are within a 0.25-mile/0.4-kilometer walk from every home)have provided enormous environmental advantage, the community benefits are notable as well. Daybreak’s walkable design encourages face-to-face interaction and connects residents with each other; in addition, the extensive trail system links neighborhoods to schools, churches, community centers, and nearby Oquirrh Lake. In 2010, a report noted that 88 percent of Daybreak students walk to school, compared to 17 percent in surrounding, less-walkable neighborhoods. While no data currently exists to prove the health benef t specif c to Daybreak’s walkable neighborhoods, it is accepted that the benefits of walkability are best guaranteed if the entire system (and not just certain specialized routes)of public corridors is walkable, which is something certainly true of the Daybreak Community.xiiiAs this development matures in years to come,Design Workshop hopes to have more substantial documentation and quantifiable evidence to support the specif c health impacts of Daybreak’s walkable design.

Open Space | The value provided by urban open space is substantial. Ecologically,open space offers a home for natural species in environments that are otherwise uninhabitable due to city development. Aesthetically, the benef t is obvious – open space supplies beauty and respite to an otherwise gray landscape. And, recreationally, open space provides opportunities for active and passive pursuits and for interaction among neighbors. (see f g. 12 and f g. 13)

Public landscapes form the backbone of the social and cultural systems at Daybreak. Of the 4,100 acres (1,659 hectares)in the entire development, up to 1,000 acres (404.7 hectares)are planned for parks and open space. Each component of the system, including the more than 22 miles (35.4 kilometers)of passive trails,recreational water features, active sporting activities, performance space, and native demonstration gardens, is carefully designed and programmed to play a specific role in community life and sized and located to appropriately serve the demographics of each specif c Daybreak village. As mentioned previously, the open space network was planned to be interconnected, intentionally promoting walkability and stormwater conveyance routes. This design concept illustrates the effectiveness of Design Workshop’s integrated approach.

Community Gardens | Community gardens and urban farms integrated into community plans are gaining ground in the United States. Such plans attract residents, support local farms, provide economic development, create opportunities for neighbor/broad community interaction, and provide educational opportunities for people of all ages. (see f g. 14)

Within Daybreak’s current open space network, there are six community gardens with over 250 individual garden plots that provide community gardens for approximately 3 percent of the current population. The gardens, carrying on a tradition of self-suff ciency in the mountain valleys or the W estern United States and teaching residents about responsible landscape methods within the Great Basin ecology, have proved to be so successful that the developer was prompted to insert additional gardens into open space areas where they had not been originally planned. Future goals are to provide enough community gardens to support up to 10 percent of the community’s population.

Art

The f nal Legacy category, Art, may be the most dif f cult one to measure and quantify and therefore, the most dif ficult category for which to create ef fective metrics. When art is applied within landscape architecture, its success becomes even more complex and diff cult to measure. After all, how does one explain something which is subtle or bold, public or private, ostracized for its statement or adored for its appeal, criticized or celebrated, excessive or re f ned, transitory or timeless? In addition, how does one measure the value of something so open to subjectivity and opinion?

Any discussion about “measuring” the impacts of art or aesthetics must begin with a disclosure of def nitions. For this discussion, art is de f ned as a dimensional attraction– something that adds artistic value to an environment, whether a public space, a street corner, or a building façade. Aesthetics def ne how things look. It is a method for characterizing beauty and feeling. Both include some level of subjectivity; however, the very act of evaluating art or aesthetics is vital to a project because it establishes a range of opinions that launch a framework for addressing basic questions such as meaning,permanence, innovation, and authenticity. DW Legacy Design®suggests that two methodologies can be applied to measuring art: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative metrics are those which can be counted: the numbers of art pieces included in a project,the inclusion of an art museum, performing arts center, or public arts programming in a project; whether a visual artist was engaged in a collaborative process; or what venues for public performance are included in the design. Public reaction to these issues is vital to measuring outcomes. W as the public engaged in the public art process, or asked to assess the visual quality of an existing landscape or to comment on the quality of a proposed design? Is there a contingent valuation methodology in place that addresses the public’s willingness to pay for public art and accept the responsibility that comes with adding community benefit to a landscape? Does public art foster opportunity for a community to discuss and determine its approach to art or its collective idea of art’s value? Qualitative metrics are a bit more nebulous, suggesting that “good” art(subjectively def ned as beautiful, charismatic, or ful f lling a communal need)attracts similar components. While such measures don’t ensure a consistent end result, they do increase the chances that a successful aesthetic component or identity will be a part of the end result. (see f g. 15)

When used to achieve a speci f c outcome, art, in any form, becomes measurable because it is attached to something with identity and character. The intellectual and emotional content inherent in the creation of a space – from the compositional idea to the spatial layout to the materials used – becomes a showcase. Measurement can be applied to the manner in which these ideas converge, including the applied aesthetics and narrative qualities inherent in the art itself, and the health and human safety of the community that interacts with the art.If art becomes a successful focal point by elevating the community culture and stability of the surrounding environment, then it has probably succeeded in intent. The number of art pieces present in a streetscape or the existence of a performing arts center in a new community is no doubt important, but far more essential to this discussion is the qualitative authenticity of the art. If art – in whatever form it takes – adds signi f cance and distinction, then it has achieved a specif c outcome and it can be measured.

The Daybreak Community’s art is the community structure and its native aesthetic.Quantitative evidence of the value of these elements is challenging to obtain; however,proof of their aesthetic value can be perceived from the community’s economic,environmental, and community successes, as have been discussed earlier. The obvious correlation is that, once again, achieved targets in any of the four Legacy categories will produce impacts and affect elements in some or all of the remaining categories.

Site Specif city | Design Workshop feels that taking the site’s location into account while planning and designing helps link a project to its surroundings. Using site specificity as a design strategy requires a thorough understanding of the cultural, environmental,and economic systems at work. In addition, it helps dif ferentiate the project from other locations and experiences, allowing residents and visitors to feel deeply connected to the site and also to the region in which it sits and the people who live there. This sense of place and identity can imbue an area as large as a region or de f ne an area as small as a village or garden.

For the Daybreak Community, the design intent was to root the landscape within its region and create a new authentic, forward-thinking, Rocky Mountain landscape that acknowledges the past while it meets the environmental challenges of today and embraces fresh aesthetic forms. The landscapes are intentional, artistic expressions of their natural and cultural context. Innovative, geometric landforms and battered gabion walls constructed of reclaimed waste rock from the Bingham Mine express connections to the region’s heritage. The forms recall the geometrical waste rock slopes of the mine that is the backdrop to the community but are softened by native grasses and plant communities. Since the community is a man-made construction, no attempt was made to make the open space look “natural” or like unspoiled nature. Rather the manmade nature of the project was celebrated through intention, geometric forms that were planted with water-wise plants – nature AND culture, environment AND community were fused to create a new aesthetic rooted in the environmental and cultural context of the community. Instead of going to waste, over 43,500 tons (39.5 million kilograms)of recycled mine rock were re-used throughout the landscape. This reinforces connections to the mine through the color, texture and forms that can be seen on the hillsides behind the community. Native plants including bitterbrush, elderberry, and rabbitbrush connect the community to its natural history and create wildlife corridors that run to the mountains and replicate native the region’s vegetative patterns. (see f g. 16)

Hillside Park offers a sculpted landscape abstraction of natural foothill forms and vernacular water courses. The water canal serves as an outfall and aeration channel for newly constructed Oquirrh Lake and carries water to the constructed wetlands below. Poplar windrows along the canal recall the iconic early Mormon pioneer tree plantings along irrigation ditches that W estern writer Wallace Stegner dubbed “The Mormon Landscape.” The riparian corridor fosters wildlife habitat and supports a growing cottonwood gallery. Water courses also serve as a storm water conveyance system leading to infiltration basins where 100 percent of a 100-year storm is inf ltrated into the ground.

Toward Synthesis

As previously mentioned, Design W orkshop believes that the most compelling places are those where environment, economics, community, and art intersect. And, relatedly,one of the f rm’s highest pursuits has been to prove the value of this belief, which it has aimed to do through a performance-based research methodology. This methodology allows the firm to gauge the progress, execution, and quality of its work against a project’s intended goals. The transparency and relevance of the metrics relate to desired outcomes while they also work toward synthesis with the other chosen objectives.

A comprehensive look into how Design W orkshop employed its performance-based methodology into the parks and open space network of South Jordan, Utah’s Daybreak Community, illustrates the impact of this process on the region as well as on the f rm itself. The project’s narrative provides examples to advance the notion that quality, rigor,and accountability in the practice of landscape architecture will generate results that meet today’s needs and goals while preserving opportunities for tomorrow.

Whether centered around metrics like Design W orkshop’s or not, an evidencebased approach is landscape architecture’s key to analyzing and to learning from accomplishments and failures in planning and built work. Individuals and firms who undertake this approach will discover value and great benefit to themselves, their projects and the profession overall.

Notes

i As Atul Gawande explains in his 2009 book The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, published by Picador,“[Checklists]not only offer the possibility of verif i cation but also instill a kind of discipline of higher performance” (p 36)and “Checklists…established a higher standard of baseline performance” (pg 39). Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. New York, New York: Picador, 2009.

ii Kurt Culbertson. Memo to Design Workshop Staff. “Metrics for Sustainability,” January 6, 2002.

iii This quadruple-bottom-line approach is an expansion of triple-bottom-line (TBL)accounting, a phrase fi rst coined by Freer Spreckley in the 1981 publication ‘Social Audit – A Management Took for Co-operative Working’ which expands traditional reporting to include environmental and social performance in addition to fi nancial performance.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triple_bottom_line. [accessed May 15, 2013].

iv http://www.usa.com/south-jordan-ut-weather.htm [accessed June 15, 2013].

v “The results of a sustained effort.” http://www.daybreakutah.com/why/sustainability/learn-more [accessed May 12, 2013].

vi “Daybreak Environmentally Friendly Real Estate, But How?” http://inside-real-estate.com/leeyoungblood/2009/08/19/daybreak-environmentally-friendly-real-estate-but-how/ [accessed May 12, 2013].

vii “Benef i ts of Going Native.” http://www.ncsu.edu/goingnative/whygo/benef i ts.html [accessed May 12, 2013].

viii “Carbon Footprint.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_footprint [accessed May 12, 2013].

ix If you build it, will they walk to school? http://daybreak-beta.location3.com/if-you-build-it-will-they-walk-to-school[accessed June 16, 2012].

x The average U.S. household’s carbon footprint is 48 tons of carbon dioxide per year. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_footprint [accessed May 12, 2013].

xi Geoffrey J. Booth. “The Sustainability Dividend: Environmental Science delivers Kennecott Land a competitive advantage.” Developer Magazine, 26-32.

xii Ibid.

xiii “Walkability.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walkability [accessed May 10, 2013].

About the author:

Natalie Grillo has over 10 years’ experience in writing, editing and public relations. A graduate of Taylor University,she began her career in non-pro f t communications and public relations, working speci f cally to create, ref ne and streamline all marketing and communications program collateral. In 2005, she accepted a position with Design Workshop where she served, in part, as both writer and editor on a variety of projects until 2013. Now a freelance writer, Natalie excels in clear, direct and appropriate communication for a given audience or project.