GO HOME, CHINA YOU’RE DRUNK

2013-07-24黄原竟

B Y G I N G E R H U A N G (黄原竟)

GO HOME, CHINA YOU’RE DRUNK

B Y G I N G E R H U A N G (黄原竟)

A brief history of prohibition in China

一部酒禁的历史

Istereotype for a hero is that of a burly, broadshouldered swordsman who can down an entire bowl of wine in one gulp and slam it down with enough force to break the table, exclaiming in a thundering roar, “Good wine (好酒 hǎojiǔ)!” Such scenes appear with alarming frequency in the 2011 show “Outlaws of the Marsh” (《水浒传》Shuǐhǔ Zhuàn), adapted from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) novel of the same name. The famous story tells of 108 outlaws who form a bandit troupe and wage guerilla warfare upon the Song Dynasty (960-1279) authority. Each of the 108 is a great hero with the power of wine running through their veins. Understandably, viewers were shocked when an Anhui TV station decided to announce that“Outlaws” would have several drinking scenes removed, in order to downplay the darker side of drinking. The TV station’s precautions immediately became a joke, but it was not the first time that wine had been on trial for eroding public morals. The uninhibited modern drinker would be the envy of the thirsty Chinese of old, as the history of prohibition in China can be traced back thousands of years. Those who challenged these laws faced stiff penalties such as imprisonment, fines, and even death. Still it is apparent that, for better or worse, the world of wine is growing more than ever.

The first historical record of prohibition in China came soon after it was invented. China’s counterpart to Dionysus, Yidi (仪狄), lived during the crossroads of China’s tribal period and the first dynasty, Xia (2070 B.C.-1600 B.C.). Yidi is credited with making the first pot of wine and offered it to Yu (禹), the sage chief. Yu found it pleasing and sweet, but he also detected the dangerous seduction of this novel beverage and commented that it would lure a future king into losing his kingdom. Instead of rewarding Yidi, Yu ordered a ban on brewing wine altogether.

THOSE WHO DRANK IN GROUPS WOULD BE EXECUTED IN THE CAPITAL, AND OFFICIALS WHO DID NOT PROPERLY ENFORCE THE PROHIBITION WOULD ALSO FACE THE DEATH PENALTY

Yu, however, wasn’t able to keep his people sober for long; his son became the first king of the Xia Dynasty and quickly lifted the ban after his father’s death. Soon, wine became a ceremonial drink: its most crucial use was as an offering in rituals to the gods, contained in massive bronze basins that could reach up to the size of a bathtub. These containers were adorned with carvingsof mythical animals, strange monsters and elaborate script. After the rituals were complete, all attendants could partake in consuming the wine, with the host’s permission. These rituals are still alive today, although they have been altered throughout history. Liquor, for example, is still offered to the dead on Tomb-Sweeping Day (清明节 Qīngmíng Jié).

Wine may have pleased the spirits, but humans risked their lives to drink it. In the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046 B.C.-771 B.C.) the Duke of Zhou decreed that: “It is the will of Heaven that our ministers and our people should drink only during major sacrificial rituals.” The Duke ruled with great emphasis on these rituals and social ranks and implemented prohibition on alcohol that bordered on cruelty: those who drank in groups would be executed in the capital, and officials who did not properly enforce the prohibition would also face the death penalty.

Historians and writers in later periods seem to confirm Yu’s prediction and wine was blamed for causing the fall of the Xia and Shang dynasties (1600 B.C.-1046 B.C.). The final rulers of both dynasties are said to have been excessive drinkers. The last king of the Shang Dynasty, King Zhou (纣王), known for throwing detractors and enemies into pits of snakes and torturous executions, was also known for building a pond of wine and a whole forest made up of trees adorned with pieces of meat. Here his subjects courted each other and engaged in orgiastic celebration, all while drinking. As hedonistic as this all sounds, modern historians posit that these depictions of lasciviousness were added much later, and question whether the liberal consumption of alcohol actually played a role in the downfall of these empires.

Brewing techniques in ancient Chinese history were crude and consisted of three main types. The first, and least valuable kind was freshly brewed and contained fermented grain; the second also contained fermented grain but was stored in a cellar for some time to mellow. The third was called qing wine (清酒), fermented and clear.

As time passed, banning wine in order to save the country from succumbing to decadence and rot was still in practice, although the consequences were less severe. A humorous conversation between the minister Chunyu Kun (淳于髡) and the King of Qi (齐威王Qí Wēiwáng) during the Warring States period (476 B.C.-221 B.C.) shows just how much social norms had changed. When asked about how much he could drink, Chunyu answered, “I can get drunk on a dou (斗), and I can get drunk on a dan (石). (Dou, an ancient measurement, is 10 liters, and a dan is 100 liters.) It all depends on where and with whom. If your highness makes me drink at a palatial feast, one dou is enough to floor me; with family acquaintances, two dou at most; reuniting with old friends, I can drink six dou, but if I’m in a marketplace in the countryside, where men and women sit together and are all entertained by drinking games, I’m so happy that I can drink a whole dan.”

These examples of booze-ability often engaged philosophers and court officials: Confucius, considering himself a disciple of the Duke of Zhou, often grievously lamented that the traditions and rituals of the Zhou Dynasty that brought order (and banned wine) had been all but lost. From Chunyu Kun’s tales, Confucius had good reason to grieve.

During the violent Three Kingdoms period

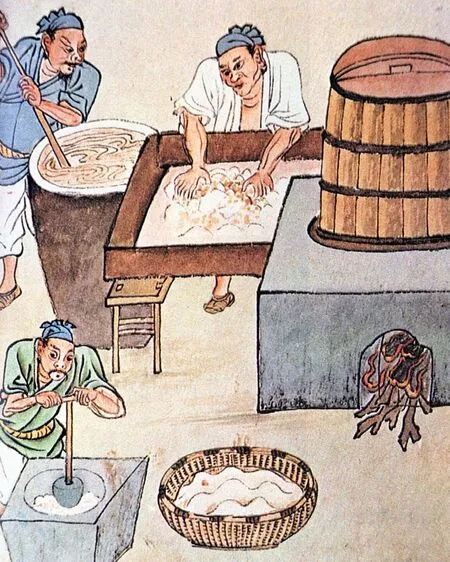

HOW WINE WAS BREWED IN THE MING DYNASTY

The illustration below is from a Ming Dynasty medical book entitled “A Collection of Herbal Genres” (《本草品汇精要》Běncǎo Pǐnhuì Jīngyào). The image depicts the most crucial and fundamental steps of wine brewing:

1. Pound grain with a stone mortar

2. Steam the pounded grain

3. Spread out the steamed grain, cool to a lukewarm temperature and blend with wine yeast

4. Ferment in a large clay jar(220-280), the role of wine in Chinese society was still under major political scrutiny. Cao Cao (曹操), a warlord and the founding emperor of the Northern Wei dynasty (386-534), fancied himself as a poet, and one of his best known poems “Short Ballad” (《短歌行》Duǎngē Xíng ) is a well-versed elegy to a jug of wine:

"SING WHEN YOU DRINK! BECAUSE LIFE IS BRIEF."

MAKING WINE YEAST

Sing when you drink! Because life is brief; Like evaporating dews it goes past, And days slip away painfully fast. Over the feast I sing, high-spirited, Yet my mind remains afflicted. What can rid me of my worries? Nothing else than Dukang wine.

Duì jiǔ dāng gē, rénshēng jǐhé?

Pìrú zhāolù, qù rì kǔ duō.

Kǎi dāng yǐ kāng, yōu sī nán wàng,

Hé yǐ jiěyōu, wéiyǒu Dù Kāng!

对酒当歌,人生几何?

譬如朝露,去日苦多。

慨当以慷,忧思难忘。

何以解忧,唯有杜康!

However, in Peking Opera, Cao is portrayed as a plotting hypocrite. During the war, he issued a ban on alcohol in order to save grain for the military, but the opera implies that this was done under the guise of it being good for the people. He ordered that all those who brewed, sold and drank wine should be beheaded. Kong Rong (孔融), a well-known cynic of Cao Cao’s authority, wrote a pointed defense of wine, arguing that without it, many countries wouldn’t exist. In his satirical retort, he challenged Cao Cao to ban marriage, as failed marriages had been disastrous to governance as well. This incident contributed to Cao’s grudge against him and, according to dramatizations of the affair, Cao ordered the execution of Kong Rong and his entire family.

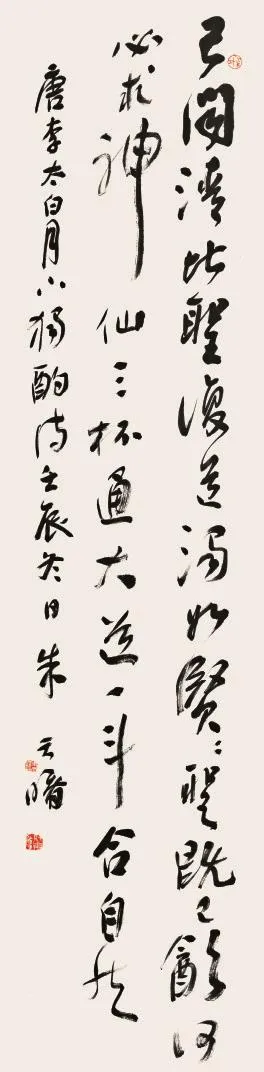

Apart from Kong Rong, most people were quiet about their distaste for prohibition and instead turned to drinking underground. In order to keep their activities on the down low, people turned to synonyms and each kind of wine was given a proxy name. Wine with fermented grain was respectfully called “the wise man” (贤人 xiánrén), and the more coveted clear wine was called “the saint” (圣人 shèngrén). These pseudonyms outlasted Cao Cao’s prohibition and even appeared in Tang Dynasty (618-907) poems three centuries later. Li Bai (李白), one of Tang’s most important poets, is nicknamed the “wine immortal” (酒仙 jiǔxiān). In one of his poems, 《月下独酌》(Yuèxià Dúzhuó, “Drinking Alone Under the Moon”) dedicated to wine, he played on the pun:

I’ve heard that clear wine is as good as a saint; And that cloudy wine is as good as a wise man. As saintliness and wisdom are within my vessel, What else do I desire from deities above? With three cups I’m freed of all bonds, And with a dou I am One with Nature. It is enough that we know those secret pleasures; Don’t reveal it to those who are sober.

Yǐ wén qīng bǐ shèng, fù dào zhuó rú xián.

Xiánshèng jì yǐ yǐn, hébì qiú shénxiān.

sān bēi tōng dàdào, yī dǒu hé zìrán.

Dàndé jiǔ zhōng qù, wù wèi xǐngzhě chuán.

已闻清比圣,复道浊如贤。

贤圣既已饮,何必求神仙。

三杯通大道,一斗合自然。

但得酒中趣,勿为醒者传。

The illustration below is from “The Exploitation of the Works of Nature”(《天工开物》Tiāngōng Kāiwù), a Ming Dynasty encyclopedia on agriculture and technology. It shows the initial step of making wine yeast—preparing rice. “Soak the rice in water for seven days, after which the rice will give out a repelling, horrible smell. Put it into a flowing brook—the brook will take away some of the smell—and then steam, and the smell will turn into a nice aroma.”

Semi-cursive script calligraphy by Zhu Tianshu (朱天曙), content excerpted from the poem “Drinking Alone under the Moon” by Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai

HAN XIZAI’S NIGHT BANQUETS

《韩熙载夜宴图》

This silk roll painting by Gu Hongzhong (顾闳中, 910-980) is from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-960). The central figure in each of the five sections is Han Xizai, a preeminent minister of the day. It is widely considered that in order to divert attention from his own political aspirations, Han indulged himself in music, women and wine.

In order to ratify his suspicions of Han, Emperor Li Yu sent a painter to Han’s mansion with the task of reporting on Han’s life and depicting it on canvas. The resulting three-meter-long roll is divided into five conjunct sections, each one smoothly flowing into the next. The first scene portrays a concert, complete with drinking and feasting; the second shows a party accompanied with music and dancing; the third shows Han and his guests taking a breather in-between the festivities; the fourth shows female musicians playing the flute and finally in the fifth, Han’s guests depart as he flirts outrageously with them all. As the night goes on Han seems to look more and more detached and stonyfaced, despite the merriment happening around him.

The painting, considered a milestone in Chinese portraiture, is currently housed in Beijing’s Forbidden Palace Museum.

Despite the fact that wine can be traced back to the very beginning of civilization, Chinese liquor, or baijiu (白酒) had a rather late start. Like vodka and brandy, producing baijiu requires distillation. In ancient China, people drank wine with an alcohol content under 20%, due to a lack of distillation techniques. Not until the Song Dynasty did people start to drink an early form of baijiu which was less distilled. Because of the heating process involved, the baijiu of the time was called shaojiu (烧酒, heated wine), a name that still persists in China’s rural areas.

The Wei, Jin, Tang and Song dynasties were periods when the government allowed the liquor to flow. The Song was an exceptional case as the government monopolized on the brewing and selling of liquor to increase revenue. In the Ming novel “A Bag of Wisdom” (《智囊》Zhìnáng) by Feng Menglong (冯梦龙), a young woman turns in her mother-in-law for brewing wine at home. By law, her mother-in-law should have been whipped, but instead the judge had the young woman whipped, because he valued family relationships over the law.

These lax policies made for good stories and during this period, wine had romantic connotations; it was connected with artistic talent, fine poetry, spiritual nobility and unruliness in politics. In the Jin Dynasty (265-420), there were seven literary giants known as the“Seven Wise Men of the Bamboo Wood” (竹林七贤Zhúlínqīxián). They drank excessively and wrote brilliantly. One of them was Liu Ling (刘伶), a talented musician, who even had his servant follow his donkey cart everywhere with a shovel: “In case that I die drinking, bury me at the very site of my death.”

In the Tang and Song dynasties, wine became the essential element for all things poetry-related. People drank when parting from good friends, when it snowed or when the flowers bloomed, when they felt down or just when spending time with friends. With this in mind,

The Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai (李白, 701-762), as depicted in the center, is one of the most honored drunkards in China's history

“IN CASE THAT I DIE DRINKING, BURY ME AT THE VERY SITE OF MY DEATH.”

300 of the 1400 poems by Du Fu (杜甫), the “saint of poetry” (诗圣 shīshèng), mention wine. Li Bai wrote over 130 poems mentioning wine and died from his love of drink, according to the historical record “Old Book of Tang” (《旧唐书》Jiùtángshū). The female poet Li Qingzhao (李清照) has only 58 poems left to posterity, and, in 28 of them, she was positively trashed! Drinking at the time was even considered genteel: in the Qing novel “The Dream of the Red Chamber”(《红楼梦》Hónglóumèng), the protagonists’ lives seem to consist only of incessant drinking and playing drinking games that challenge their lyrical talents.

Times have certainly changed: modern Chinese drinkers have not experienced the kind of strictlyenforced bans that their predecessors faced. On the contrary, Chinese are sometimes forced to drink, and go so far as to consider inebriation to be part of their job. In a society built on a web of relationships, or guanxi (关系), drinking is an important way of getting work done, signing contracts and networking. However, in 2007, the local government of Xinyang, Henan Province, issued a ban on government workers from drinking at lunchtime, so they wouldn’t come back from lunch at 3 p.m., staggering into the office. In just six months, the third-tier city government saved 43 million RMB on liquor—the cost of building 50 primary schools. In 2009, 27 Political Congress Committee members proposed that prohibition be expanded nationwide, but no further word has come out since. The proposal is still hanging in limbo and it seems hard to imagine how China could actually function under prohibition.