Driver Zhou

2015-03-26

Driver Zhou

It’s the third time Zhou Jianxun has woken up to the alarm clock. It’s three in the morning. The temperature has dropped to -30 degrees Celsius. The sky is pitch black, and the mountains around him are snow-covered, quiet, and vast. He sleeps in his truck, a massive 22-wheeler. He starts the engine and lets it run for a while and then dozes off again. He cannot let her freeze during the night, otherwise he won’t be able to start her in the morning and the shipment will be late.

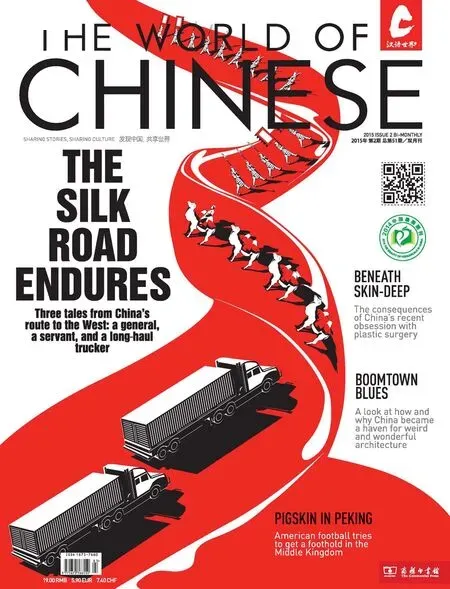

Zhou, a 44-year-old driver, spends most of his time during the year delivering cargo from Urumqi to destinations in Central Asia, which is referred to as the“Five Countries” among the Xinjiang locals. This time Zhou is hauling over 50 tons of clothes produced in China’s southern manufacturing centers in his truck, and he has about one week to go from Turugart, the boundary post close to Kashgar, Xinjiang, to get to Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan.

Chinese commodities, especially clothes and electronic goods, are popular in Central Asia, although they have a reputation of being cheap and temporary. The cargo Zhou is shipping will go to wholesale markets that mainly sell Chinese merchandise. Many of the stalls are run by Chinese, especially Chinese from Fujian and Guangdong provinces—best known for their entrepreneurship.

China’s authorities are also fxated on the route Zhou is running. For eight years, China tried to get this “desert Silk Road” to be recognized as a UNESCO heritage site; they fnally succeeded in June, 2014, a win for the nations of China, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. This Silk Road, recognized by UNESCO as running for 5,000 kilometers, can be traced back to the second century BCE. It prospered from the sixth to 12th century, and fell into disuse in the 16th century.

To some extent, via the recognition of these heritage sites, China is rebuilding a centuries-old bond with its estranged neighbors. For hundreds of years before the Qing Dynasty (1616 – 1911), Central Asian countries functioned as a passage between China, Europe, India, and Africa. Taking a brisk walk through time, going back over 1,400 years to the Tang Dynasty in the Silk Road’s heyday, the route bustled with people from all walks of life heading to Chang’an, the international metropolis that was the capital of the Tang Dynasty. The inclusiveness of Chang’an was startling considering the relative homogeny of contemporary Chinese cities.

There were sizable Central Asian communities, and they infuenced not only the Chinese people’s lifestyles, religions, and arts, but also occupied high ranking positions in the government. The path to all this wondrous history was cut in the beginning of the Qing Dynasty. For hundreds of years after that, warfare and upheavals continued almost ceaselessly between and involving Central Asia, the Qing, and Russia. In the past two decades, however, the Silk Road has undergone a revitalization with efforts from both China and nations in Central Asia—both in terms of trade and culture. The ancient caravans on camels over treacherous mountain passes have been replaced today by shipping companies like the one Zhou works for and modern highways and railways that keep drivers and travelers safe. Just a few years ago there were only pebble paths, and now most main roads have been rebuilt with asphalt—mainly by China. The biggest exports from China to Central Asia, other than clothes and electronics, are construction materials and, of course, construction teams. This boom in local infrastructure has brought with it a signifcant infux of Chinese workers—traveling in their wake are Chinese restaurants, advertisements, and amenities that are becoming more common in Central Asia. China, in turn, imports mainly oil, gas, and raw materials.

These Chinese pioneers, who like to pride themselves on being able to survive anywhere, are making new homes in these countries. “The general economic conditions in these countries is really not that good, and the Chinese are very well off compared to most locals,” says Zhou. These Chinese immigrants are among the upper-middle class in these countries, butthey do not ft in all that well. A small portion of the Chinese are of the Hui Muslim ethnic minority, whose earlier generations migrated on a large scale to Central Asia in the 1960s, but now most Chinese there are of the Han ethnicity. In exceptional cases, those who have spent time in these countries may marry locals and speak their language, but it’s certainly not the norm. Most Chinese limit their lives to their own communities, retaining their own habits and lifestyle— never really considering the beautiful plateau under clear blue sky their home. It may be that the cultural gap for them is too wide; many Chinese there are just seeking a livelihood. Apart from the language barrier, they also do not understand the locals’ religion or culture, societies that can sometimes still be recognized by their distinct Soviet qualities.

THAT FORMER CONSTRUCTlON CORP MAKES UP ABOUT 12 PERCENT OF THE POPULATlON OF THE REGlON

The same cultural gap exists at the other end of the contemporary Silk Road as well. Zhou’s parents, like millions of Han Chinese in Xinjiang, were relocated there from other parts of China, which are often referred to by locals as “inland”. This was because they were members of the “Construction Corps” in the 1950s—part of the government’s efforts to develop Xinjiang and strengthen the security of the western border. Now, that former Construction Corp makes up about 12 percent of the population of the region. However, having grown up in the Uyghur Autonomous Region doesn’t mean that Zhou can speak the Uyghur language and it doesn’t mean that he knows very much about the religion or culture. For Zhou and those like him trying to eke out a living on this trade route, it is simply a means to an end.

After hundreds of years apart, it seems that getting UNESCO recognition for the historical value of the “Silk Road”is a lot easier than bringing back the cultural mix, vigor, and prosperity that the road once represented. But, perhaps this is only temporary; with the new Silk Road getting up and running, perhaps—along with the electronics, construction, materials, and textiles—a little understanding and culture might fow over that ancient route once again.

- GlNGER HUANG (黄原竟)