Consultation-liaison psychiatry in China

2012-07-10JianlinJIChenyuYE

Jianlin JI*, Chenyu YE

· Review ·

Consultation-liaison psychiatry in China

Jianlin JI*, Chenyu YE

Consultation-liaison psychiatry (CLP) was first established in China after liberation in 1949. It has developed more rapidly over the last two decades but, despite major regional differences in the level of CLP, the overall practice of CLP in the country remains quite basic, largely limited to case-based consultation with other medical departments. There is little ongoing collaboration between departments of psychiatry and other departments, and medical students and nonpsychiatric clinicians rarely get training in CLP.

1. Introduction

According to Lipowski,[1]the article published by George Henry in theAmerican Journal of Psychiatryin 1929 marked the launch of consultation-liaison psychiatry (CLP) as a scientific discipline. Initially, the CLP doctor was scoffed at as ‘a pleasant, pipe-smoking gentleman wearing a tweed jacket who, with much time on his hands, proselytized for the psychosocial model’.[2]Such stereotypes have changed over time. Today, CLP physicians are expected to have the multidisciplinary knowledge and skills needed to carry out psychiatric interviews; to conduct risk assessments and manage threats of suicide, assault, and agitation in common clinical settings; to interpret laboratory results; and to consider the physical, legal, and ethical issues when managing the psychiatric problems of patients with concurrent physical illnesses. They are also required to possess good communication skills when interacting with non-psychiatrists, other health care professionals, and patients' family members.[2]The specialty of CLP was initially launched in the United States and subsequently adopted worldwide, but its development in China has not been a smooth one. Prior to the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, psychiatric units had been established in some general hospitals in China, but there are no reports of CLP-type services. After 1949, the departments of psychiatry and clinical psychology established in many general hospitals started to provide CLP services, particularly in university teaching hospitals. In parallel with the rapid economic and social reforms that started in China in the 1980s, the concept of CLP has become more widely accepted by medical professionals and administrators; this has facilitated increased cooperation between departments of psychiatry and other clinical departments. This article briefly introduces the development of CLP in China and its current status.

2. Definition, content and basic modes of operation

According to Lipowski, CLP may be defined as the part of clinical psychiatry which includes all diagnostic, therapeutic, teaching, and research activities of psychiatrists (as well as psychiatric social workers and nurses) in the non-psychiatric divisions of a general hospital.[3]The clinical services include the provision of psychiatric consultations for non-psychiatric medical staff and promotion of the psychosocial perspective of care (‘liaison’). The education component includes training basic psychiatric concepts and the psychosocial perspective of medical care to medical students, residents and other care providers in non-psychiatric departments. The research component includes study of the assessment and management of the psychological and behavioral problems that occur in persons with physical illnesses, co-morbid medical and psychiatric disorders seen in general medical settings, and the evaluation of CLP clinical services and education.[4]

CLP in general hospitals in China can be divided into three main types.

a) Consultation-liaison between specialty psychiatric hospitals and general hospitals. This is common in China because most general hospitals do not have departments of psychiatry. An example is the psychiatric service system for general hospitals in Beijing developed by Professor Quiyun Li at the Mental Health Institute of the Beijing University that subsequently evolved into the General Hospital Psychiatry Network establish under the auspices of the Chinese Society of Psychiatry.

b) CLP within general hospitals that have their own departments of psychiatry, a modelthat has become increasingly common after university teaching hospitals started to develop departments of psychiatry in the 1990s. Different models for doing this have evolved. In some centers there are psychiatric inpatient and CLP services in the general hospital (e.g., the West China Hospital affiliated to Sichuan University, the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, and the Tongji Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Tongji University). In some centers there is a psychiatry or behavioral medicine outpatient department (but no inpatient services) in the general hospital (e.g., Zhongshan Hospital at Fudan University and Peking Union Medical College Hospital)—similar to behavioral medicine departments in the United States and psychological medicine departments in the United Kingdom. And in some cases smaller general hospitals have been partially converted to specialty psychiatric hospitals while retaining most of their general medical inpatient services (e.g., Changzhou No. 102 Hospital, Jiangsu Province).

c) Despite the increased CLP presence, a large proportion of general hospitals in the country still lack psychiatric support so they make neurologists responsible for psychological problems that arise in their patients. In these settings depression, anxiety and sleep disorders among outpatients and delirium and behavior disorders among inpatients are referred to general hospital neurologists for assessment and management. Psychiatrists from specialty hospitals are only called in if it proves impossible to control a patient’s behavior.

3. Main services

3.1 Basic mental health services in general hospitals

In the 1990s, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a multi-center study in 15 countries to investigate the epidemiology of mental health disorders in patients treated in general medical institutions.[5]In Shanghai, which was one of the collaborative centers, 1 673 outpatients treated in general hospitals were enrolled. Depressive disorders were the most prevalent—the prevalence of depression and dysthymia were 4.0% and 0.6%, respectively; other less common conditions included neurasthenia, generalized anxiety, somatoform disorders, alcohol dependence, depressive neurosis, panic disorders, and phobic disorders.

In 2002 He and colleagues[6]conducted a national project on mental health service utilization. They found that the utilization of inpatient mental health services was much greater in large municipal and provincial institutions than in smaller institutions, which had much lower occupancy rates. The mean annual number of mental health outpatient visits at the institutions was 8707, but the range in the number of visits varied by 30-fold. Typically the outpatient volume at psychiatric hospitals operated by the Ministry of Health was greater than at those operated by the Ministry of Civil Affairs Hospitals (which more commonly provide services to patients with chronic mental illnesses). The library services at the psychiatric hospitals were extremely limited, subscribing to a median of four academic journals. Among the psychiatric hospitals 19% had no residency training program and those that did have a training program lacked a uniform method and curriculum for training clinical psychiatrists. This shows the poor overall status of psychiatric services and training in the country, a fact that has seriously undermined the development of liaison psychiatry.

In 2003 a review of CLP in China by Yu[7]highlighted the weakness of the CLP subspecialty in China. There was no network of practitioners, no professional organization, no plan for the development of CLP, and no system for training and accrediting CLP subspecialists. The psychiatric consultation rate was very low, the highest reported rate in general medical wards was 1.78%. The survey found that almost all CLP work was focused on providing diagnoses and treatment for difficult patients on general medical services; there was no genuine consultation between psychiatrists, non-psychiatric clinicians and patients, and there was no research about developing an appropriate China-specific model of CLP. The ability of non-psychiatric clinicians to identify medically ill individuals with co-morbid psychiatric disorders was very limited.

The many studies about CLP conducted over the last decade have included few well-designed studies that provide an accurate overview of the status of CLP in the country. One 2004 study by Yu and colleagues[8]reported that 17 of the 29 general hospitals in Shanghai surveyed (59%) had established departments of psychiatry or psychology. The rate of referral for psychiatric assessment in the hospitals with psychiatry departments was 0.63% while the rate in the hospitals without a psychiatry department was 0.10%. None of the hospitals with a psychiatry department had established a CLP group composed of psychiatrists and non-psychiatrists and 55% of the hospitals had never or only rarely provided CLP services. So on the one hand Shanghai—which is generally better resourced and progressive in mental health than most other parts of the country—has been successful in getting psychiatric services into general hospitals but on the other hand it has been less successful in integrating CLP services as part of the overall service delivery system of the hospitals. The limited CLP services available at the hospitals with departments of psychiatry are single case-based consultations; there are no full-time CLP psychiatrists who regularly participate in routine clinical care in non-psychiatric departments.

In 2002 Professor Desen Yang,[9]a renowned seniorpsychiatrist from Hunan Province, wrote about his vision for the coming decade: ‘It’s necessary to expand the mental health workforce in the thousands of general hospitals around the country at the county level or above and establish departments of psychological medicine or psychiatry within these hospitals. Mental health clinicians at general hospitals should be composed of psychiatrists (with 5-year medical degrees) and well-trained psychotherapists, and their numbers should increase from the current 100 individuals to at least 1000 individuals.’ In 2003 the Ministry of Health promulgated theChina Mental Health Plan(2002-2010)[10]which stated that ‘General hospitals shall establish departments of psychology (outpatient) or departments of psychiatry (outpatient).’The plan also set targets for rates of recognition of depression in district-level and municipal-level general hospitals and in county-level general hospitals: by 2005 the recognition rates were expected to be 40% and 30%, respectively and by 2010 the recognition rates were expected to reach 60% and 50%, respectively.

Unfortunately, these lofty goals were not achieved. Official reports for 2012 suggest that there are 20 000 specialized mental health practitioners in the country, most of whom work in large specialty hospitals in Shanghai, Beijing, Changsha and other economically developed parts of the country. It is unclear how many of them work in CLP at general medical hospitals. A 2008 dissertation by Ge[11]entitled ‘Status of medical workers in the psychological outpatient departments of general hospitals in Wuhan City’ reported that only 22.4% of the general hospitals in Wuhan offered mental health services (77% of which were high-level tertiary hospitals), and that only 15.4% of the staff at these outpatient mental health departments were trained psychiatrists (48.7% were other physicians and 25.6% had degrees in psychology). Clearly, CLP in China still has much room for improvement.

3.2 Studies on psychiatric consultation in general hospitals

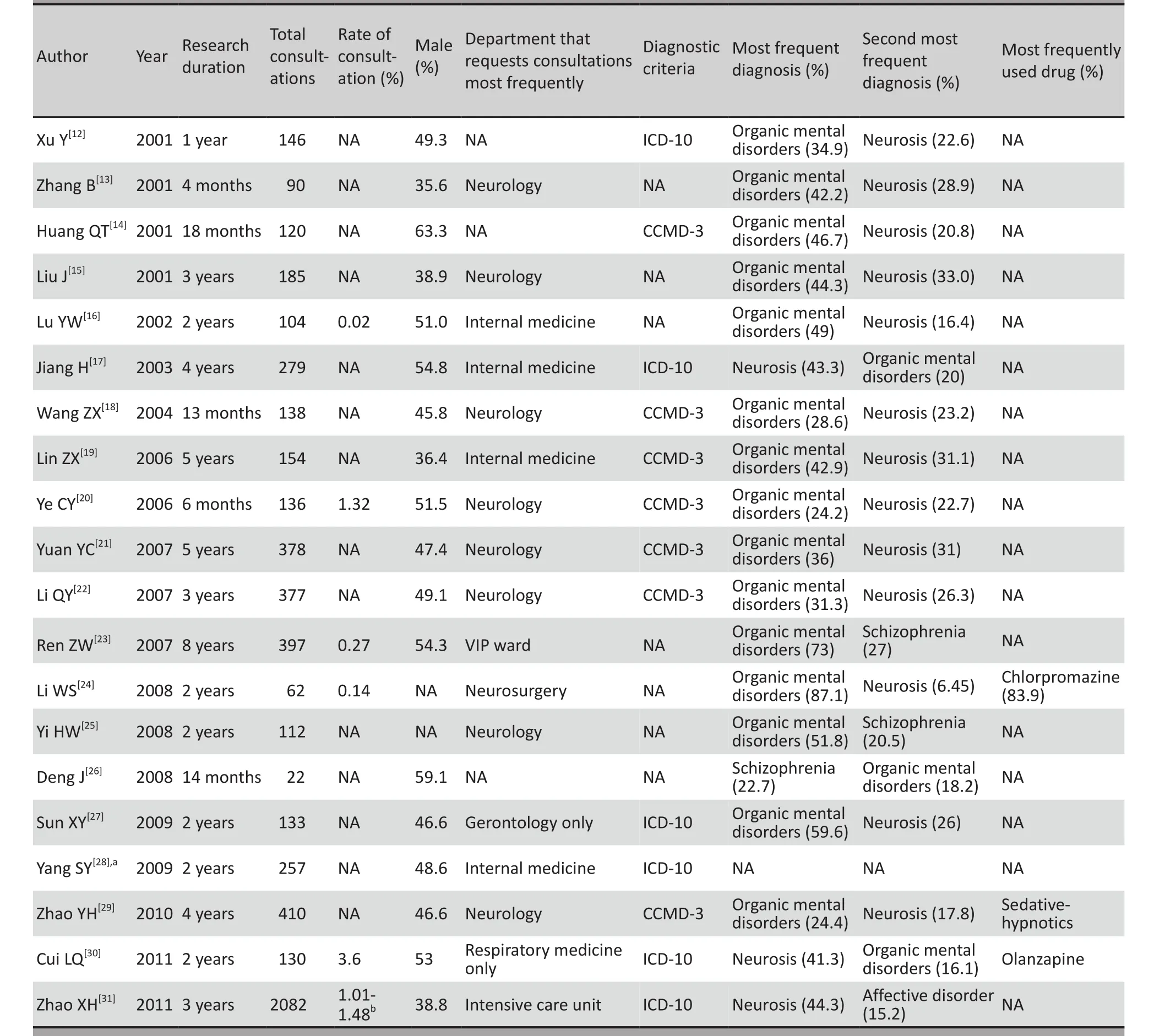

At present, China's CLP research is still largely limited to psychiatric consultation in general hospitals. Using the keyword ‘consultation-liaison psychiatry’, the authors searched for relevant literature in the comprehensive China Wanfang database over the last 10 years. The results for the 20 articles identified[12-31]are shown in Table 1.

The study designs varied. Only one of the studies was prospective;[20]all the others were retrospective. Most of the studies are descriptions of the proportions of referrals from different clinical departments and proportions of different diagnoses in the patients seen. Only 6 of the 20 studies provided consultation rates (ranging from 0.02 to 3.6%) and only 14 of the studies reported the diagnostic criteria that were used to make the diagnosis. Most consultation requests come from departments of neurology, possibly due to the historical relationship of the two departments in China (up until 1994 psychiatry in China was a sub-discipline of neurology). Organic mental disorder was the most frequent reason for consultation, accounting for 24 to 87% of all referrals. The findings varied by geographic region and by type of hospital. In the tertiary (highestlevel) hospitals in socioeconomically developed areas, the consultation rate was high and the proportion of referrals with organic mental disorder was relatively low (neurosis was a more common diagnosis in these settings); but in the less developed parts of the country consultation rates were low and the majority of referrals had an organic mental disorder or some other severe mental disorder. In recent years the study designs have improved and the range of issues addressed has expanded: more studies now include psychiatric follow-up of referred patients,[20]comparisons between emergency consultation and regular consultation,[28]and descriptions of the psychiatric consultation processes in specific medical departments.[27,30]

3.3 Cooperation with and training for other departments

The main focus of CLP in China continues to be psychiatric consultations for disturbed patients in medical departments, but there has also been a gradual increase in the adoption of psychiatric theories and practices by other departments.

3.3.1 Psychosomatic skill training

In 2003, the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine at the University of Freiburg, Germany, together with the Department of Psychiatry at Tongji Hospital in Shanghai launched a national continuing medical education (CME) project focusing on psychosomatic medicine that has sponsored a series of five annual training workshops on psychosomatic medical care in China. A subsequent collaborative ‘Asia-Link’ project between the University of Freiburg, Tongji University and other institutions in Australia, Vietnam, and Laos (funded by the European Union in 2005) enabled Asian psychiatrists and other physicians to receive training in the basic skills of psychosomatic medicine. The training sessions included lectures, exercises using role playing, group discussions, on-site case interviewing, Balint groups, and family sculpture exercises. To date over 100 physicians from different clinical departments have attended the 60-hour courses; they report that the training is very practical because, in part, it promotes the concepts of ‘human-centeredness’ and ‘psychosomatic concordance’. The success of the course has stimulated the development of similar CME projects: a Balint group symposium chaired by Professor Jing Wei at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital has continued for four years; the Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University has promoted the development of a local Balint group in Shanghai; and there are plans to establish the Chinese Balint Federation (CBF) in 2012.[32-35]

Table 1. Research on psychiatric consultation in China in the past decade

3.3.2‘Psycho-cardiology Medicine’

Cardiovascular expert Professor Dayi Hu proposed the concept of ‘Psycho-cardiology Medicine’[36]in 2006. This approach integrates an understanding of the many biomedical risk factors for heart disease with an understanding of the psychological characteristics that are needed for individuals to effectively reduce their risk of heart disease in the complex social world and medical service network in which they have to function. Cardiologists and psychiatrists have jointly compiled training materials for Psycho-cardiology Medicine, that include both detailed descriptions of the neurophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and of the common psychological problems that can occur in individuals who experience these conditions. There have also been a number of related studies: Ling and colleagues[37]found that 6.9% of internal medicine outpatients have anxiety symptoms, 3.7% have depressive symptoms and 1.3% have both anxiety and depressive symptoms; Fan and colleagues[38]found that the anxiety and depressive symptoms occurring in internal medicine outpatients vary by gender and age; and Lin and colleagues[39]reported that the quality of life of internal medicine outpatients at general hospitals is closely associated with the severity and duration of concurrent anxiety and depressive symptoms.

3.3.3 CLP services in other departments

It is not uncommon for patients with physical problems to have a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. The psychological problems detected at organ transplantation centers are particularly prominent. Despite a relatively large number of mental health studies related to transplants conducted in China in recent years, the quality of most such studies is quite low: among 10 such studies reported in the last decade only one[40]was conducted by a psychiatrist (a descriptive summary); the results of the studies are almost entirely based on the self-rating depression scale (SDS) and/or the self-rating anxiety scales (SAS); the studies either lacked controls or selected inappropriate controls; and there is inadequate description and standardization of the psychological intervention provided. Therefore, any conclusions drawn from such studies must be interpreted with caution. With few exceptions, studies on the psychological status of patients following treatment for malignant tumors suffer from the same limitations. However, recently Ye and colleagues carried out a well standardized study among patients receiving a heart transplantation[41]and there has been a well-designed study on the nursing of patients with malignant tumors conducted by a psychiatrist.[42]So there is some hope that the quality of research in the area will improve in the future.

By comparison, CLP studies carried out in internal medicine settings have been of a higher caliber. Zuo and colleagues[43-45]have carried out several in-depth CLP studies about psychosocial factors and cognitive functioning among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and Zhou and colleagues[46]conducted impressive CLP research on hemodialysis in the early 1990s.

3.3.4 Post-disaster CLP

One area of CLP which is comparatively well developed is the provision of post-disaster services. Psychological intervention offered by psychiatrists to families of the victims in the 2002 ‘Northern Airlines Crash’ was the first post-disaster mental health intervention in China. During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, CLP psychiatrists made significant contributions to the management of the psychological reactions of patients, medical staff, and the general public. After the Wenchuan earthquake in 2008, there was a surge of research relating to CLP services during the disaster: these studies identified large numbers of earthquake survivors suffering from mental health problems[47-49]and suggested that early provision of psychological assistance was practical and effective.[50]In addition to post-disaster intervention for victims, attention should also be paid to the prevention and management of the psychological stress of the rescuers. Tian and colleagues[51]highlighted the importance of secondary traumatic stress in rescuers.[51,52]

3.3.5 Psychiatric intervention and medical treatment in general hospitals

CLP differs from mainstream psychiatry in several ways.[53]One of the main differences is that in most psychiatric services the patient presents himself or herself to the psychiatrist for management of a perceived psychiatric problem whereas in CLP the psychiatrist approaches the patient. It is inevitable that in some cases consultation from the psychiatrist may be unwelcome and the patient may react with surprise, denial or anger, amongst other emotions. Another difference is the environment where the consultation takes place: traditional psychotherapy is usually conducted in a relatively private treatment room which facilitates doctor-patient communication, but CLP consultations in general hospitals are typically conducted in noisy environments with relatively little privacy. Although there are several psychotherapy regimens that could be undertaken in general hospitals (e.g., cognitive therapy, introspective treatment, group therapy, family therapy, etc.) in most cases patients in general hospital settings are most willing to accept general supportive psychotherapy. Initially the psychiatrist develops a good therapeutic relationship with the patient by ‘considerate listening’ to the patient’s problems and concerns, decreasing the intensity of their emotional response to their situation. The psychiatrist subsequently provides gentle encouragement to increase the patient’s selfconfidence and psychological resilience and, thus, restore their psychosocial functioning back to baseline levels.

General hospitals are usually cautious in their use of psychotropic drug, preferring to have them administered by psychiatrists. All the main psychiatric medications are available in general hospitals but they are typically used at lower doses than in specialty psychiatric settings. The Chinese Society of Psychiatry of the Chinese Medical Association has published a series of clinical guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of seven common mental illnesses (i.e., schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, dementia, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder) that can be used in general hospital settings. A simplified version of the guidelines for the treatment of anxiety disorders is also available. Recently neurologists and psychiatrists have jointly formulated theConsensus of Experts on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Nervous System Disease Associated with Depression and Anxiety Disorders[54]and theConsensus Expert Panel on the Definition, Diagnosis and Drug Treatment of Insomnia[55,56]both of which are suitable for use by clinicians in general hospitals. And a recent volume entitledPsychiatry in the General Hospital, co-edited by Professors Wenyuan Wu and Jianlin Ji, provides a comprehensive overview of the recognition and management of psychiatric and psychosomatic problems that can occur in patients treated in general hospitals.

4. Difficulties and future outlook

Despite 20 years of substantive research and increased administrative support CLP in China has not seen a fundamental change. The main working model for CLP in China remains being asked to provide case-limited consultations. Collaboration with other departments is usually limited to collaborative research projects, and research fellows in CLP have no trajectory for professional development after their graduation. Some of the leading institutions in big cities have services that are approaching international standards but the level of development of CLP across the country is very imbalanced and the overall quality leaves much to be desired.

CLP is not yet part of the curriculum for most medical schools and even where it is part of the curriculum the training primarily consists of theoretical classes taught by social scientists that are completely unrelated to the necessary skills in doctor-patient communication. Psychiatrists who assume the role of CLP physicians in general hospitals receive little specialized training beyond basic psychiatric training, so it is difficult for them to hone the skills needed to work effectively in the general hospital setting: evaluation and management of comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions; crisis intervention; psychopharmacology in medically ill patients; communicating with critically ill and terminal patients; and so forth. The continuing education opportunities for CLP physicians that are available are limited to a few famous institutions in big cities.

But Rome was not built in a day. Although CLP in China is still lagging far behind CLP in other countries, based on the accumulated experience of the last two decades and the continuing support of the government it will ultimately grow and prosper. Chinese CLP physicians are, as posited by Lipowski,[1]part of the small number of health care professionals in the country who have the broad perspectives on human health needed to provide comprehensive assessment and treatment for individuals with comorbid physical and psychological disorders.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

1. Lipowski ZJ. Consultation-liaison psychiatry at century’s end.Psychosomatics1992; 33(2): 128-133.

2. Wise MG, Rundell JR.Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry.2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

3. Lipowski ZJ. Current trends in consultation-liaison psychiatry.Can J Psychiatry1983; 28(5): 329-338.

4. Lipowski ZJ. Consultation-liaison psychiatry: the first half century.Gen Hosp Psychiatry1986; 8(5): 305-315.

5. Xiao SF, Yan HQ, Lu YF, Bi H, Bu JY, Xiao ZP, et al. World Health Organization collaborative study on psychological disorders in primary health care: the results from Shanghai.Chin J Psychiatry1997; 30(2): 90-94. (in Chinese)

6. He YL, Zhu ZQ, Zhang MY. Current status of psychiatric outpatient services in China.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry2002; 14(suppl): 12-13; 18. (in Chinese)

7. Yu DH. Current status and future plans for consultation-liaison psychiatry in China.J Clin Psychol Med2003; 13(1): 52-53. (in Chinese)

8. Yu DH, Wu WY, Zhang MY. Current situation of mental health service in general hospitals in Shanghai.Chin J Psychiatry2004; 37(3): 176-178. (in Chinese)

9. Yang DS. Prospects of community mental health for the new century in China.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry2002; 14(2): 104-106. (in Chinese)

10. Ministry of Health, Ministry of Civil Affairs, Ministry of Public Security and the All China Disabled Persons Federation of People’s Republic of China. China’s working plan for mental health (2002-2010).Shanghai Arch Psychiatry2003; 15(2): 125-128. (in Chinese)

11. Ge Q. Study on situation of mental health personnel in the clinics of general hospitals of Wuhan: 4-6. (in Chinese) http://www.cnki. net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=cmfd&dbname=cmfd2010 &filename=2009143015.nh&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldTTGJhYlNlZ2 hYdlN6bGV1a05ERmc1a0pON0FYWFZQTlJ4RVlNLzJ5S0l0Rm9oa FF3Kys2Yw==&p= [Accessed 18 April, 2012]

12. Xu Y, Ji JL. Practice of consultation-liaison psychiatry in general hospital.Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science2001; 10(5): 437-438. (in Chinese)

13. Zhang B. An analysis of 90 cases of psychiatric consultations in a general hospital.West China Medical Journal2001; 16(1): 37-38. (in Chinese)

14. Huang QT, Li JL, Wang XQ, Wang Z. Consultation analysis of somatic disease accompanied by psychological disorder in general hospital.Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation2002; 6(7): 1076.

15. Liu J, Li ZW, Liu SH, Yuan CY, Ge GJ. Analysis of 185 cases in the psychiatric consultation-liaison at a general hospital.Shandong Arch Psychiatry2001; 14(3): 190-192. (in Chinese)

16. Lu YW, Shen QJ, Hu JZ, Tang ZR, Liu TB, Hu CY, et al. A two years consultation reviewed of mental department in Shenzhen hospitals.Medical J of Chinese People’s Health2002; 14(3): 135-137. (in Chinese)

17. Jiang H, Jia JH, Tang ZX. Analysis of consultation-liaison psychiatry for inpatients in general hospitals.Chin J Rehabil Theory Practice2003; 9(11): 695. (in Chinese)

18. Wang ZX. Analysis of 138 patients treated by the psychiatric consultation-liaison service at a general hospital.Chinese Medicine of Factory and Mine2004; 17(5):407-408. (in Chinese)

19. Lin ZX, Zou XB, Lin JD, Lu L, Lü D. Departments applying for consultation-liaison psychiatry and distribution of diagnosed different psychiatric diseases in general hospitals: analysis of 154 cases.Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation2006; 10(14): 172-173. (in Chinese)

20. Ye CY, Shen YF, Ling Z, Ji JL. Psychiatric consultation for medical patients and follow-up study in general hospital.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry2006; 18(1): 20-23. (in Chinese)

21. Yuan YC. Clinical study of 378 in-patients in a general hospital seen by the consultation-liaison psychiatry service.Journal of Luzhou Medical College2007; 30(1): 60-62. (in Chinese)

22. Li QY. Analysis of the consultation-liaison psychiatry service in a general hospital.Journal of Baotou Medical College2007; 23(1): 24-25. (in Chinese)

23. Ren ZW, Yang ZX, Zhang YQ. Analysis of the consultation-liaison psychiatry service provided the inpatient in general hospital.China Journal of Health Psychology2007; 15(5):432-434. (in Chinese)

24. Li WS. Consultation-liaison psychiatry service in general hospitals.J Benbu Med Coll2008; 33(2): 212-213. (in Chinese)

25. Yi HW. Analysis of 112 cases of inter-hospital psychiatric consultation.China Practical Medicine2008; 3(4): 69-70. (in Chinese)

26. Deng J. Clinical features of 22 patients referred to a psychiatric consultation-liaison service in a general hospital.Medical Journal of Chinese People’s Health2008; 20(5): 430-431. (in Chinese)

27. Sun XY, Tan CX, Lü QY. Consultation liaison psychiatry for elderly patients in general hospital: analysis of 131 cases.Journal of Psychiatry2009; 22(1): 5-7. (in Chinese)

28. Yang SY, Li JL. Results of consultation-liaison referral for general hospital inpatients with a comorbid psychiatric illness.J Clin Psychosom Dis2009; 6(15): 544-545. (in Chinese)

29. Zhao YH, Dai FQ. Analysis of 410 psychiatric consultation cases in a general hospital.Journal of Qiqihar Medical College2010, 31(19): 3055-3056. (in Chinese)

30. Cui LQ, Huang YP, Yu JL. Analysis of consultation liaison for respiratory patients at a general hospital.MMJC2011; 13(5): 28-31. (in Chinese)

31. Zhao XH, Hong X, Shi LL, Li L, Cao JY, Wei J. Analysis of data from consultation–liaison psychiatry service for the inpatients in a tertiary general hospital.Chinese Ment Health J2011; 25(1): 30-34. (in Chinese)

32. Luo YL, Wu WY, Lu Z, Cui HS, Shen Y. Role playing and Balint group in psychiatric training course.Chinese Medical Ethics2010; 23(3):92, 111. (in Chinese)

33. Chen H, Liu WJ, Ye CY, Zhang HX, Pan KP. Application of the Balint group in general hospital.J Intern Med Concepts Pract2011; 6(3): 184-187. (in Chinese)

34. Liu WJ, Ye CY, Chen H, Ji JL. Qualitative study of doctor Balint group cases in general hospital.Chinese Ment Health J2012; 26(2): 91-95. (in Chinese)

35. Yang H. Balint groups.Chinese General Practice2007; 10(13): 1077-1079. (in Chinese)

36. Hu DY. Integrated management of cardiovascular disease and mental disorder— discussion of ‘psycho-cardiology medicine’.Chinese Journal for Clinicians2006; 34(5): 2-3. (in Chinese)

37. Ling Z, Sha L, Ji JL, Yin J, Zhu L, Fan Q, et al. Use of hospital anxiety and depression scale (Chinese version) in Chinese outpatient in department of internal medicine.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry2010; 22(4): 204-206, 223. (in Chinese)

38. Fan Q, Ji JL, Xiao ZP, Sha L, Shi YJ, Mei L, et al. Application of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) among medical outpatients.Chinese Mental Health Journal2010; 24(5): 325-328. (in Chinese)

39. Lin GZ, Fan Q, Mei L, Shen XH, Shi YJ, Xu XD, et al. Quality of life of medical outpatients with anxiety in a general hospital.Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Medical Science)2011; 31(1): 43-46. (in Chinese)

40. Su G, Liu JF, Lu GY. Assessment of psychological disorders during the peri-operation period for hepatic transplantation.Chin J Psychiatry2001; 34(1): 59. (in Chinese)

41. Ye CY, Chen H. Psychological problem in adults after heart transplantation.Chin J Organ Transplant2011; 32(10): 636-637. (in Chinese)

42. Wang J, Zou YZ, Tang LL, Li J, Zhang D, Jin S, et al. Personality, coping style, immunity function in the patients with gastric cancer.Chin J Psychiatry2001; 34(3): 172-175. (in Chinese)

43. Zuo LJ, Xu JM, Ji JL, Jiang KD, Zhao JC, Yu YP. Cognitive function of type 2 diabetics with micro-angiopathy.Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology2001; 9(2): 102-104. (in Chinese)

44. Zuo LJ, Xu JM, Gao X. The relationship between the psychological disturbance and metabolic control in the adults with type 2 diabetes.Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science1999; 8(4): 266-267. (in Chinese)

45. Zuo LJ, Ji JL, Xu JM, Gao X, Gu NF, Zhao JC, et al. A pilot study of cognitive function and related factors among the patients with type 2 diabetes.Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science2001, 10(2): 95-97. (in Chinese)

46. Zhou AQ, Ji JL, Xu JM. Investigation on psychological distress of the dialystic patients with end-stage renal failure.Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science1994, 3(2): 73-75. (in Chinese)

47. Li J, Guo JX, Xu WJ, Yin QY, Hu HY, Shen F, et al. The psychological problems in the wounded of Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan.Chin J Nerv MentDis 2008, 34(9): 523-524. (in Chinese)

48. Wen SL, Wang XL, Tao J, Gan ZY, Zheng LR, Li RJ, et al. Psychological status of survivors one week after the Sichuan earthquake.Chin J Nerv Ment Dis2008; 34(9): 525-527. (in Chinese)

49. Qiu CJ, Yang YC. Case report of acute stress reaction after the huge ‘5.12’ earthquake.Chin J Nerv Ment Dis2008; 34(9): 527-528. (in Chinese)

50. Wang DM, Feng XJ. Analysis of psycho salvation for the wounded in the Wenchuan ‘5.12’ earthquake.China Jouranl of Health Psychology2008; 16(9): 1080. (in Chinese)

51. Tian JC, Li J, Wang JB, Xu CQ, Wei SQ. The effect of mental intervention on anxious-depressive mood in earthquake relieving officers and soldiers.J Clin Psychosom Dis2008; 14(5): 412-413. (in Chinese)

52. Liao JM, Luo YM, Feng SM. Self-care for disaster relief workers during the provision of relief services.Chin J Nerv Ment Dis2008; 34(9): 517-519. (in Chinese)

53. Ye CY, Ji JL. Psychotherapy in consultation-liaison psychiatry.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry2005; 17(4): 242-244. (in Chinese)

54. Expert group for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the nervous system with comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the nervous system with comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders.Chin J Intern Med2008; 47(1): 80-83. (in Chinese)

55. Expert group for the definition, diagnosis and pharmacological treatment of insomnia. Expert consensus for the definition, diagnosis and pharmacological treatment of insomnia (draft).Chin J Neurol2006; 39(2): 141-143. (in Chinese)

56. Expert group for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the nervous system with comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the nervous system with comorbid depressive or anxiety disorders (revised).Chin J Intern Med2011; 50(9): 799-805. (in Chinese)

10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.03.001

Department of Psychological Medicine, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

*Correspondence: jianlinji@yahoo.com.cn

杂志排行

上海精神医学的其它文章

- Retrospective analysis of treatment effectiveness among patients in Mianyang Municipality enrolled in the national community management program for schizophrenia

- Effectiveness of a rehabilitative program that integrates hospital and community services for patients with schizophrenia in one community in Shanghai

- Randomized controlled trial on adjunctive cognitive remediation therapy for chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia

- Superoxide dismutase activity and malondialdehyde levels in patients with travel-induced psychosis

- Cross-sectional study on the relationship between life events and mental health of secondary school students in Shanghai, China

- How to avoid missing data and the problems they pose: design considerations