Risk factors and incidence of acute pyogenic cholangitis

2012-07-10

Hangzhou, China

Risk factors and incidence of acute pyogenic cholangitis

Yun-Sheng Qin, Qi-Yong Li, Fu-Chun Yang and Shu-Sen Zheng

Hangzhou, China

BACKGROUND:Acute cholangitis varies from mild to severe form. Acute suppurative cholangitis (ASC), the severe form of acute cholangitis, is a fatal disease and requires urgent biliary decompression. Which patients are at a high risk of ASC and need emergency drainage is still unclear. The present study aimed to identify the factors for determining early-stage ASC and distinguishing ASC from acute cholangitis.

METHODS:We analyzed 359 consecutive patients with acute cholangitis who had been admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 2004 to May 2011. Emergency endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was carried out in all patients to decompress or clear the stones by experienced endoscopists. Clinical and therapeutic data were collected, and univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify the potential risk factors of ASC.

RESULTS:Of the 359 patients, 1 was excluded because of failure of ERCP drainage. Of the remaining 358 patients with an average age of 62.7 years (range 17-90), 162 were diagnosed with ASC, and 196 with non-ASC. ENBD catheters were placed in 343 patients (95.8%), of whom 182 patients had stones removed at the same time, and plastic stent was placed in 25 patients (7.0%). Clinical conditions were improved quickly after emergency biliary drainage in all patients. Complications were identified in 11 patients (3.1%): mild pancreatitis occurred in 8 patients and hemorrhage in 3 patients. There was no mortality. Univariate analysis showed that several variables were associated with ASC: age, fever, decreased urine output, hypotension, tachycardia, abnormal white blood cell count (WBC), low platelet, high C reactive protein (CRP), and duration of the disease. Multivariateanalysis revealed that advanced age, hypotension, abnormal WBC, high CRP, and duration of the disease were independent risk factors for ASC.

CONCLUSIONS:This study demonstrates that advanced age, hypotension, abnormal WBC, high CRP, and long duration of antibiotic therapy are significantly associated with ASC. We recommend decompression by ERCP should be carried out in patients as early as possible.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2012;11:650-654)

acute cholangitis; suppurative; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Introduction

Acute cholangitis is an infectious disease resulting from partial or complete obstruction of the biliary tract. Biliary tract obstruction and secondary bacterial colonization lead to infection. The common causes are choledocholithiasis, benign or malignant strictures, indwelling biliary stent malfunction and bilioenteric anastomotic malfunction. The causative agents are intestinal microflora, mainly aerobic microorganisms.[1]As a rule, the majority of biliary infections does not lead to acute cholangitis. But when the obstruction raises the intraductal pressure to the level high enough to cause reduction in bile flow or cholestasis, bacterial proliferation and colonization are initiated, resulting in acute cholangitis. If the inflammatory process is prolonged and the pressure of bile duct continues to rise, just as acute suppurative cholangitis (ASC), cholangiovenous or cholangiolymphatic reflux will be hard to avoid. The infection may enter the bloodstream and lead to bacteremia or sepsis. Then, acute cholangitis develops from local infection to the systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome (SIRS), and the clinical features of the patients deteriorate quickly.

The major cause of cholangitis is choledocholithiasis. The Charcot's triad or Reynold's pentad (fever, jaundice,pain, shock and abnormal mental status) constitutes the most frequent symptomatology. Diagnosis is made by the history of the disease, laboratory tests reflecting systemic infection, and clinical imaging, such as abdominal ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, which indicate the signs of biliary obstruction and various etiologies.[2,3]

Formerly, the mainstay of therapy of acute cholangitis was appropriate antibiotic coverage, supported by intravenous hydration. The death rate of acute cholangitis was extremely high,[4,5]especially for ASC, a serious form of acute cholangitis, which refers to accumulation of purulence in the bile duct. With the introduction of biliary decompression, especially using endoscopic techniques as the first choice,[5,6]the death rate of acute cholangitis has dropped. However, clinical features of the patients with acute cholangitis vary greatly in terms of severity, from mild to serious. The former can be treated with antibiotics alone, while the later needs urgent drainage to reduce the pressure of the biliary tract. It is difficult to determine the patients who will be in the mild or severe form. When to drain always depends on disease progression or deterioration after appropriate antibiotic therapy. The death rate of patients who do not undergo biliary drainage in good time ranges from 50% to 80%.[1,7]Consequently, it is very important to differentiate between suppurative and non-suppurative cholangitis. If risk factors causing suppurative cholangitis exist, earlier drainage to decompress can be carried out in patients at high risk.

This study was undertaken to identify the risk factors that could be used to determine early-stage ASC and distinguish ASC requiring urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) from acute cholangitis.

Methods

Definitions

Acute cholangitis is defined as infection rooted in the biliary system, accompanied by a higher fever (>38 ℃) for more than 24 hours. ASC is defined as acute cholangitis that fails with appropriate antibiotic therapy or associates with organs/systems dysfunction or endoscopic evidence of pyogenic bile.[4,8]

Patients and data collection

We retrospectively analyzed 359 consecutive patients with acute cholangitis who had been admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 2004 to May 2011. The diagnosis of acute cholangitis was confirmed by symptoms and signs (pain, jaundice, fever, shock and abnormal mental status), laboratory tests white blood cell count (WBC), C reactire protein (CRP) and liver function and abdominal imaging (ultrasonography and/or MRCP). Emergency ERCP procedures were performed in all patients to drain or clear the stones by experienced endoscopists.

Clinical, biochemical, etiologic and therapeutic data of these patients were gathered from the records on hospital admissions and a handbook created for ERCP procedures and follow-up in our endoscopy department. Indications for urgent drainage, the course of ERCP, ERCP diagnosis, and post-ERCP complications were recorded timely. The initial results of blood test for each patient in our hospital were used in the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by the SPSS version 17.0 for Windows. Quantitative variables were expressed as median or mean±SD, and variables associated with ASC were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Comparisons were made by using Student'sttest. Univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out to identify the potential risk factors of ASC. Statistically significant difference was defined asPvalue less than 0.05.

Results

Three hundred and fifty-eight of the 359 patients were enrolled in the study cohort. One patient was excluded because of failure of ERCP drainage. Of the remaining 358 patients (191 men and 167 women) with an average age of 62.7 years (range from 17 to 90), 162 were diagnosed with ASC and 196 were diagnosed with non-ASC.

Among the patients with ASC, 77 (47.5%) presented with Reynold's pentad, 53 (32.7%) were complicated with renal failure, and 113 (69.8%) were elderly (>75 years). In the patients with non-ASC, the indications for urgent ERCP were acute cholangitis (n=136, 69.4%), biliary pancreatitis (n=51, 26%), and acute pancreatitis with jaundice (n=9, 4.6%). ENBD was performed in 343 patients (95.8%), of which 182 patients had stones removed at the same time, and biliary plastic stent was placed in 25 patients (7.0%). Clinical conditions were improved quickly after emergency biliary drainage in all patients.

Complications were identified in 11 patients (3.1%),i.e., mild pancreatitis occurred in 8 patients and hemorrhage in 3. There was no mortality in this series.

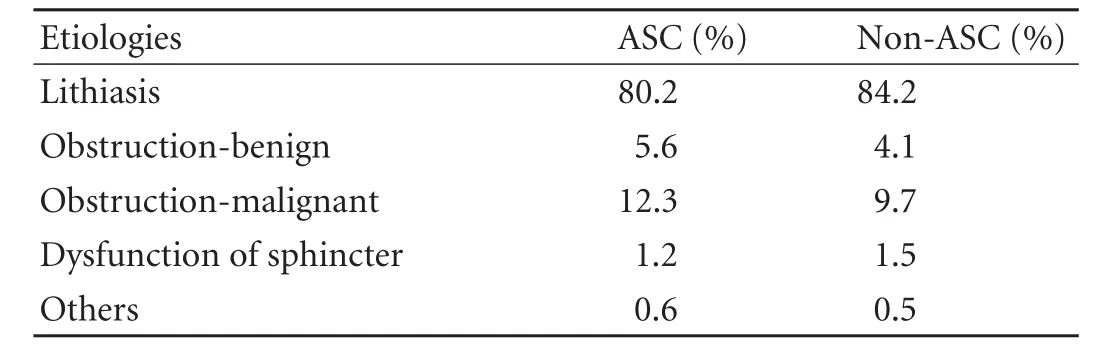

Table 1.Various etiologies of acute cholangitis

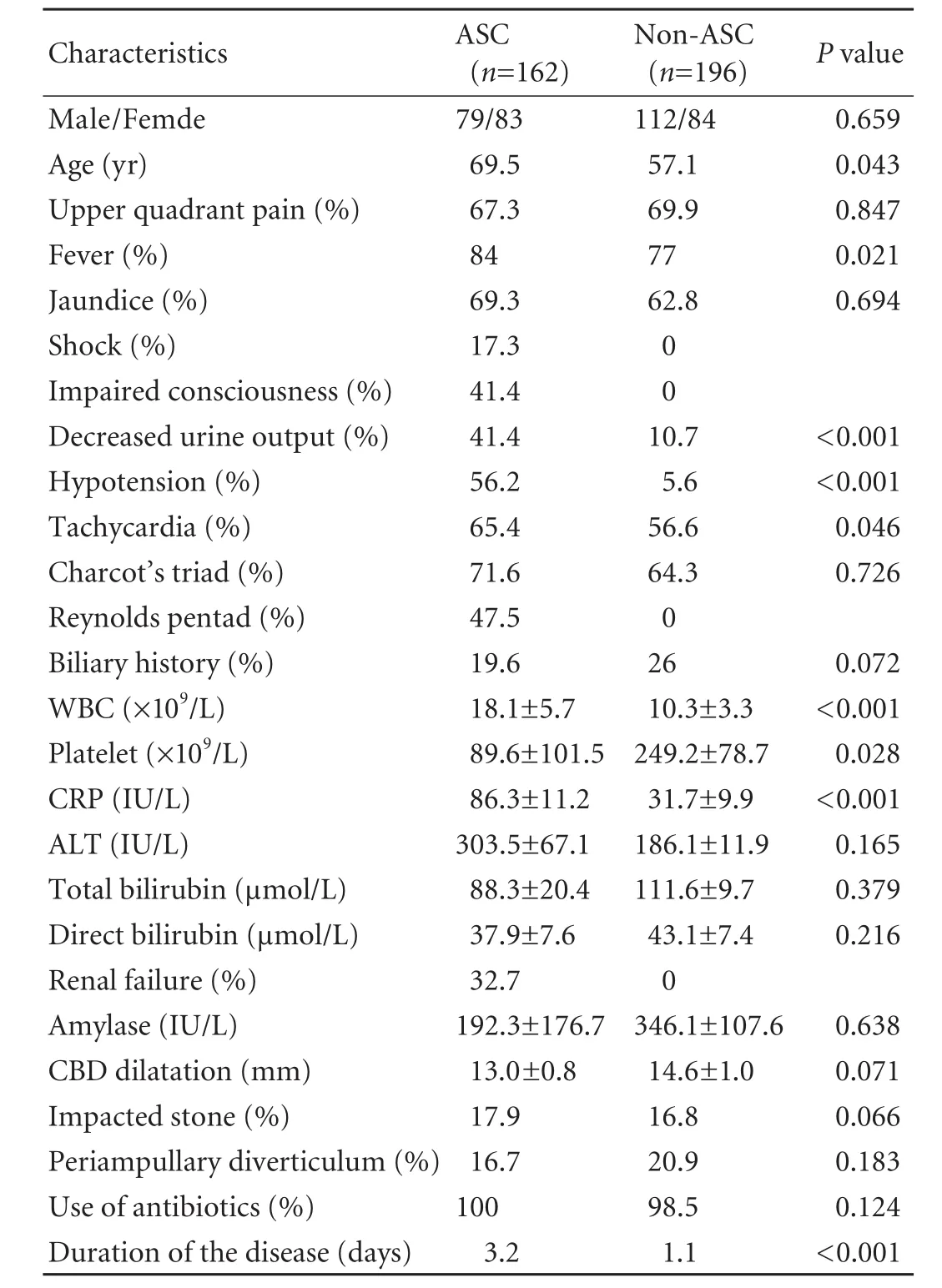

Table 2.Mean values of variables and results of univariate analysis

Table 3.Multivariate analysis of risk factors for ASC

The various etiologies of ASC or non-ASC are shown in Table 1. The mean values of the variables and the results of univariate analysis are shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis showed the following variables associated with ASC: age, fever, decreased urine output, hypotension, tachycardia, high WBC, low platelet, CRP, and duration of the disease. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that advanced age, hypotension, abnormal WBC, high CRP, and duration of the disease were independent risk factors for ASC (Table 3).

Discussion

ASC is a severe infection of the biliary tract, usually resulting from biliary obstruction. Biliary drainage for decompression is the first choice to relieve obstruction. At present, indications that warrant biliary decompression include septic shock, clinical deterioration or failure to improve.[4,9-11]The decision to decompress is made always on the basis of deterioration of the disease or failure to improve after appropriate antibiotic treatment. However, the mortality of intervention at that moment will be extremely high. On the other side, it is not necessary and feasible to urgently decompress in each patient with acute cholangitis. Therefore, early identification is the key to improve the prognosis of ASC. Identifying the risk factors of ASC would allow physicians or surgeons to determine whether patients will improve after medical treatment. It is important to identify the patients who will not improve after medical treatment, and early intervention with drainage can be applied for decompression of the bile duct.

High risk patients warranting early biliary decompression have been identified in recent studies.[8,11-15]In the present study, the following variables associated with ASC were identified by univariate analysis: age, fever, decreased urine output, hypotension, tachycardia, WBC, platelet, CRP, and duration of the disease. Multivariate analysis identified advanced age, hypotension, WBC, CRP, and duration of the disease as independent predisposing factors of ASC.

In our study, advanced age (>75 years) is an independent variable for ASC, which is also reported in other researches.[4,10,12]The reasons vary. Firstly, the incidence of acute cholangitis is higher in elderly patients than in young and middle-aged patients.[10,16,17]Secondly, misdiagnosis and a delayed diagnosis occur commonly in elderly patients with cholangitis because they often present with no typical symptoms of fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice (Charcot'striad). Thus, it is thoughtless for diagnosis based on Charcot's triad, especially in elderly patients with underlying cholangitis. Thirdly, the clinical conditions of elder patients with acute cholangitis often deteriorate suddenly and rapidly. This may ascribe to the poor relativity between symptoms and severity of illness. Finally, it is difficult to perform emergent procedures because elderly patients always have concurrent cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurologic and other systemic diseases. A previous study[17]indicates that it is safe and effective for those patients aged 90 years or above, suffering from acute cholangitis, to undergo emergency biliary decompression with ERCP. Therefore, earlier biliary decompression is recommended in elderly patients, especially those above 75 years, with low fever, mental obtundation, and less improvement after conservative treatment.

The present study indicates that abnormal WBC and CRP are the two independent risks for ASC. Abnormal WBC count is used to predict bacterial infection in clinical practice. Leukocytosis (WBC over 15×1012/L) or leukocytopenia (WBC less than 1×1012/L) indicates overwhelming bacterial infections. CRP is a biomarker and frequently used for clinical testing to indicate the presence of severe sepsis. High concentrations of serum CRP are closely related with the high risk of organ failure and death.[18]

Hypotension as a significant risk factor for ASC is a primary feature of septic shock. When the biliary obstruction raises the pressure to a high level, infection resulting from the biliary system may enter the bloodstream and lead to septicemia or sepsis. Then acute cholangitis advances from local infection to systemic inflammation. If an infection can not be controlled by appropriate antibiotic treatment, the conditions may lead to a severe drop in blood pressure and cause hypoxia and low perfusion. When the blood pressure is too low, there is an inadequate blood flow to the vital organs. It can cause multiple organ dysfunction syndromes.[4,19]The typical presentation of serious sepsis is shock with obvious hypotension, fever, and abnormal WBC count. Thus, hypotension in patients with acute cholangitis always indicates the potential fatal infection.

The data of the present study suggest that the duration of the disease is an independent risk factor, which may be due to our hospital as a tertiary referral center. A long course of the disease always means a long duration of antibiotic therapy and failured improvement after conservative treatment in other hospitals. The patients received medical treatment, and they were transferred to our hospital because of poor therapeutic effect. Most of the patients may progress to sepsis, with organ dysfunction or organ failure.[4,15]Therefore, these patients need urgent biliary decompression and organsupportive care.[21]

The development of renal dysfunction and renal failure is common in this cohort and undoubtedly is related to the combination of hypotension and hypovolemia from the production of inflammatory mediators released by severe infection.[22,23]Therefore, decreased urine output and tachycardia are identified as predictive factors by univariate analysis. The results of a recent study indicated that tachycardia (>100/min) is one of the four factors predicting the failure of initial medical treatment. In severe infection condition,[20]decreased platelet count is due to bone marrow suppression. So platelet count (<50×1012/L) is another predictive factor for ASC. Febrile state reflects host response to infection, and high fever (>39 ℃) is a prognostic factor in acute cholangitis .

In conclusion, urgent ERCP is essential in acute cholangitis associated with advanced age (>75 years), hypotension, WBC >20×1012/L or <0.5×1012/L, CRP >50 U/L, and duration of the disease >3 days. In patients with fever, decreased urine output, tachycardia, and platelet <50×1012/L, urgent ERCP is recommended to be carried out as early as possible because it is unlikely to respond to medical treatment.

Contributors:QYS and ZSS proposed the study. QYS analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. ZSS is the guarantor.

Funding:This study was supported by a grant from the Investigative Foundation of Medical Science of Zhejiang Province (2008B050).

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Mosler P. Management of acute cholangitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:121-123.

2 Lee NK, Kim S, Lee JW, Kim CW, Kim GH, Kang DH, et al. Discrimination of suppurative cholangitis from nonsuppurative cholangitis with computed tomography (CT). Eur J Radiol 2009;69:528-535.

3 Kim SW, Shin HC, Kim IY. Transient arterial enhancement of the hepatic parenchyma in patients with acute cholangitis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2009;33:398-404.

4 Wada K, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Miura F, Yoshida M, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007;14:52-58.

5 Thompson JE Jr, Tompkins RK, Longmire WP Jr. Factors in management of acute cholangitis. Ann Surg 1982;195:137-145. 6 Sharma BC, Kumar R, Agarwal N, Sarin SK. Endoscopic biliary drainage by nasobiliary drain or by stent placement in patients with acute cholangitis. Endoscopy 2005;37:439-443.

7 Salek J, Livote E, Sideridis K, Bank S. Analysis of risk factors predictive of early mortality and urgent ERCP in acute cholangitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009;43:171-175.

8 Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Sekimoto M, et al. Background: Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2007;14:1-10.

9 Lee JG. Diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:533-541.

10 Agarwal N, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Endoscopic management of acute cholangitis in elderly patients. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:6551-6555.

11 Kostrzewska M, Baniukiewicz A, Wroblewski E, Laszewicz W, Swidnicka-Siergiejko A, Piotrowska-Staworko G, et al. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and their risk factors. Adv Med Sci 2011; 56:6-12.

12 Pang YY, Chun YA. Predictors for emergency biliary decompression in acute cholangitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;18:727-731.

13 Doganay M, Yuksek YN, Daglar G, Gozalan U, Tutuncu T, Kama NA. Clinical determinants of suppurative cholangitis in malignant biliary tract obstruction. Bratisl Lek Listy 2010;111:336-339.

14 Tsujino T, Sugita R, Yoshida H, Yagioka H, Kogure H, Sasaki T, et al. Risk factors for acute suppurative cholangitis caused by bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:585-588.

15 Rosing DK, De Virgilio C, Nguyen AT, El Masry M, Kaji AH, Stabile BE. Cholangitis: analysis of admission prognostic indicators and outcomes. Am Surg 2007;73:949-954.

16 Yeom DH, Oh HJ, Son YW, Kim TH. What are the risk factors for acute suppurative cholangitis caused by common bile duct stones? Gut Liver 2010;4:363-367.

17 Hui CK, Liu CL, Lai KC, Chan SC, Hu WH, Wong WM, et al. Outcome of emergency ERCP for acute cholangitis in patients 90 years of age and older. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19: 1153-1158.

18 Lobo SM, Lobo FR, Bota DP, Lopes-Ferreira F, Soliman HM, Mélot C, et al. C-reactive protein levels correlate with mortality and organ failure in critically ill patients. Chest 2003;123:2043-2049.

19 Mosler P. Diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2011;13:166-172.

20 Hui CK, Lai KC, Yuen MF, Ng M, Lai CL, Lam SK. Acute cholangitis--predictive factors for emergency ERCP. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1633-1637.

21 Park SY, Park CH, Cho SB, Yoon KW, Lee WS, Kim HS, et al. The safety and effectiveness of endoscopic biliary decompression by plastic stent placement in acute suppurative cholangitis compared with nasobiliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:1076-1080.

22 Fujii Y, Ohuchida J, Chijiiwa K, Yano K, Imamura N, Nagano M, et al. Verification of Tokyo Guidelines for diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2012;19:487-491.

23 Hiramatsu R, Hoshino J, Imamura T, Hasegawa E, Yamanouchi M, Hayami N, et al. Acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis as a cause of acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis. Intern Med J 2011;41:506-509.

July 20, 2012

Accepted after revision October 5, 2012

Author Affiliations: Division of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery; Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health; and Key Laboratory of Organ Transplantation Zhejiang Province, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China (Qin YS, Li QY, Yang FC and Zheng SS)

Shu-Sen Zheng, MD, PhD, FACS, Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China (Tel: 86-571-87236570; Fax: 86-571-87236884; Email: shusenzheng@zju.edu.cn)

© 2012, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60240-9

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer

- Endoscopic sphincterotomy associated cholangitis in patients receiving proximal biliary self-expanding metal stents

- Biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: the endoscopic versus percutaneous approach

- Gallstone-related complications after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a prospective study

- Inhibiting the expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha attenuates lipopolysaccharide/ D-galactosamine-induced fulminant hepatic failure in mice

- Changes of serum alpha-fetoprotein and alpha-fetoprotein-L3 after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic significance