Pancreaticopleural fistula: etiology, treatment and long-term follow-up

2012-07-07KeithRobertsMariaSheridanGarethMorrisStiffandAndrewSmith

Keith J Roberts, Maria Sheridan, Gareth Morris-Stiff and Andrew M Smith

Leeds, UK

Original Article / Pancreas

Pancreaticopleural fistula: etiology, treatment and long-term follow-up

Keith J Roberts, Maria Sheridan, Gareth Morris-Stiff and Andrew M Smith

Leeds, UK

BACKGROUND:Pancreaticopleural fistula (PPF) are uncommon. Complex multidisciplinary treatment is required due to nutritional compromise and sepsis. This is the first description of long-term follow-up of patients with PPF.

METHODS:Eleven patients with PPF treated at a specialist unit were identified. Causation, investigation, treatment and outcomes were recorded.

RESULTS:Pancreatitis was the etiology of the PPF in 9 patients, and in the remaining 2 the PPF developed following distal pancreatectomy. Cross-sectional imaging demonstrated the site of duct disruption in 10 cases, with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography identifying the final case. Suppression of pancreatic exocrine secretion and percutaneous drainage formed the mainstay of treatment. Five cases resolved following pancreatic duct stent insertion and three patients required surgical treatment for established empyema. There were no complications. In all cases that resolved there has been no recurrence of PPF over a median follow-up of 50 months (range 15-62).

CONCLUSIONS:PPF is an uncommon event complicating pancreatitis or pancreatectomy; pancreatic duct disruption is the common link. A step-up approach consisting of minimally invasive techniques treats the majority with surgery needed for refractory sepsis.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2012;11:215-219)

pancreatic disease; pancreatitis; pancreatic pseudocyst

Introduction

It is well-recognized that disease processes affecting the pancreas such as acute pancreatitis and also operative interventions to manage pancreatic disease may be associated with the development of a wide range of complications. Whilst the mortality from pancreatic surgery has decreased to under 5% in specialized centers, morbidity remains high.[1]Acute pancreatitis presents a broad spectrum of disease from a mild selflimiting episode to multi-organ failure and death. A pathology common to both pancreatitis and post-surgery complications is pancreatic duct disruption with the consequential leakage of pancreatic secretions.

Pancreaticopleural fistula (PPF) is an uncommon complication of pancreatitis and of pancreatic surgery with just 52 and 2 cases, respectively, reported in the literature.[2]If pancreatic secretions track in a cranial direction they can enter the thorax via the mediastinum at the aortic hiatus or directly through the diaphragm. The majority of fistulae drain into the left hemithorax. Identifying the presence of and treating PPF presents a significant challenge. A multidisciplinary approach is required to treat these patients, some of whom require specialist endoscopic or surgical intervention within dedicated pancreatic units. We have previously presented successful short-term outcomes of managing PPF in a small cohort of patients.[3]There is little published information on long-term follow-up results. This study aimed to present the long-term outcomes of managing a group of patients with PPF.

Methods

Eleven patients with PPF were identified from a departmental database between April 2006 and June 2011. This is a retrospective review of each case identifying method of presentation, investigation, treatment and outcome. This study was undertaken to build upon our earlier experience[3]by describing the long-term followup and success or otherwise of treating patients with PPF.The St James University Hospital is a tertiary referral center with a dedicated pancreatic unit. All patients with pleural collections had fluid sent for amylase analysis confirming the presence of pancreatic fluid within the pleural space. Two patients with mediastinal collections were included in the analysis and considered as having PPF. Though it was not possible to safely obtain fluid for amylase estimation, both cases were identified as having PPF due to duct disruption being clearly identified on cross-sectional imaging with peripancreatic fluid seen to extend into the posterior mediastinum.

All patients were investigated with both CT and MRI imaging to determine the site of duct disruption and extent of fluid collections. Interventions were performed when clinically indicated. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was not routinely performed as the fidelity of cross-sectional imaging allowed identification of the site of pancreatic duct disruption and track of the fistula in each case. ERCP was performed when pancreatic duct stenting was required. We used a step-up approach whereby patient treatment consisted of: 1) diagnosis of pancreatic fistula using cross-sectional imaging supported by fluid with raised amylase content when it was possible to aspirate fluid, 2) drainage of collections internally or percutaneously where possible with repeat drainage considered for non-resolving sepsis, and endoscopic placement of a pancreatic duct stent performed after ongoing high output of percutaneous pancreatic secretion, and 3) surgical intervention required when the above techniques failed to adequately treat sepsis. Nutrition was supported by nasogastric feeding when possible or nasojejunal feeding in cases of gastric outlet obstruction or gastroparesis. Every patient received oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation (40 000-80 000 IU per meal) during each inpatient episode and continued until outpatient review. At this point, enzyme supplementation was continued on clinical grounds. The somatostatin analogue octreotide was given in every case until resolution of the fistula (200 µg subcutaneous TDS). Every case was presented at a multidisciplinary forum consisting of consultant surgeons, radiologists, endoscopists, pathologists and oncologists.

Results

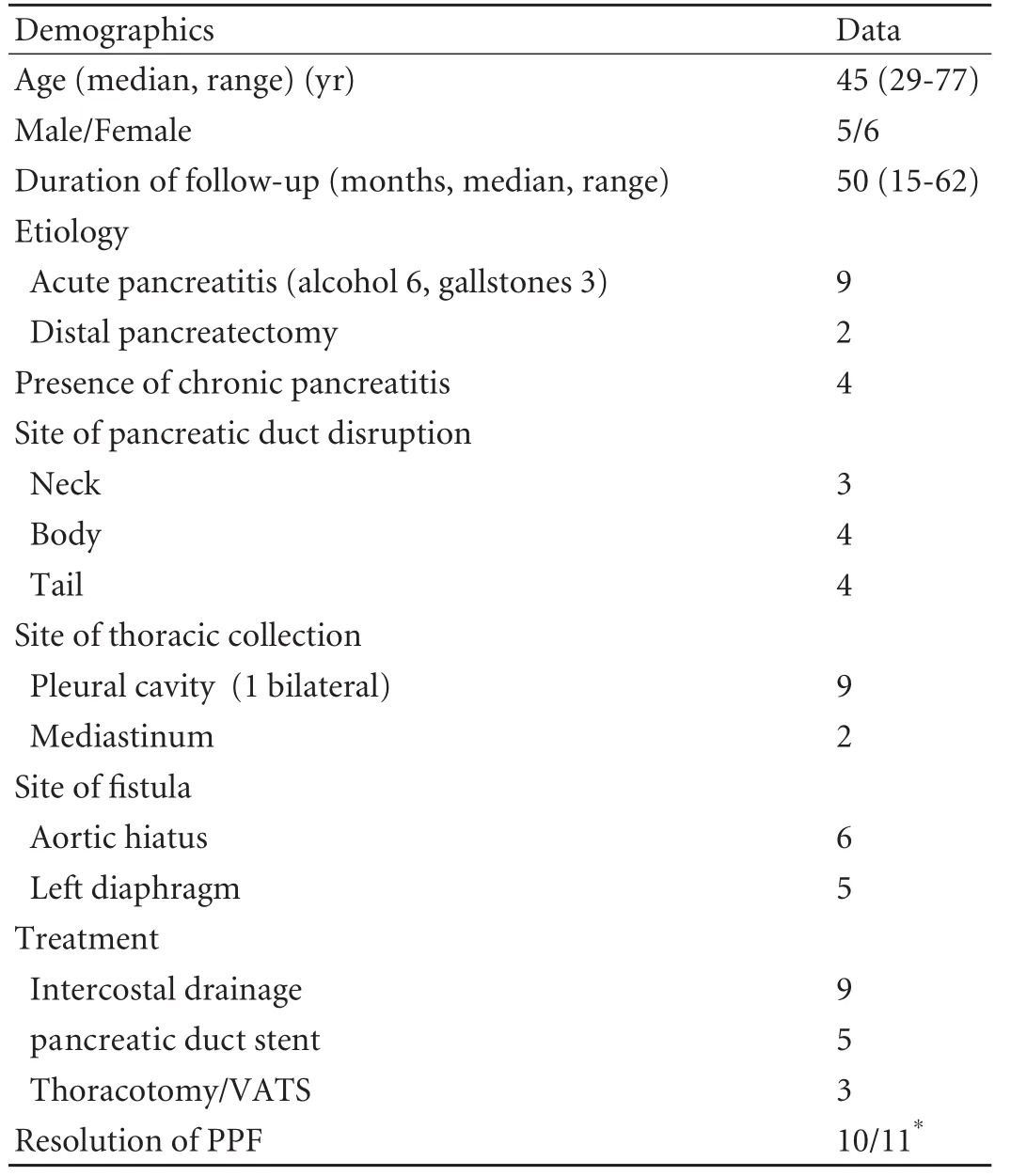

Acute pancreatitis was found in nine cases (secondary to alcohol in six cases and gallstones in three); two cases showed complications of distal pancreatectomy. There were six females. The median age was 45 years (range 29-77). The cases are summarized in Table.

Table. Group characteristic data

Presenting features

Eight patients were referred to our unit with acute pancreatitis: 6 with shortness of breath and pleural effusions, and 2 with sepsis and pleural effusions. In 2 of these patients a PPF had been diagnosed at the referring hospital. One patient presented directly to the pancreatic unit with acute necrotizing pancreatitis.

Of the 2 patients developing a PPF following distal pancreatectomy, 1 procedure was performed following traumatic disruption of the pancreas at the level of the body, and the other for a suspected malignant cystic lesion in the tail of the pancreas. Splenectomy was performed in both cases. Both patients developed left upper quadrant collections, secondary to pancreatic fistulae, and these were treated by percutaneous drainage. Despite successful treatment of these fluid collections both developed signs of sepsis, and were identified as having infected left pleural collections.

Evidence of chronic pancreatitis was visible on the index CT scans of 4 patients (one or more of dilated pancreatic duct, pancreatic calcification or pancreatic atrophy).

The median duration of inpatient admission for initial treatment of PPF was 43 days (range 9-105).

Pancreatic duct disruption and thoracic fluid collections

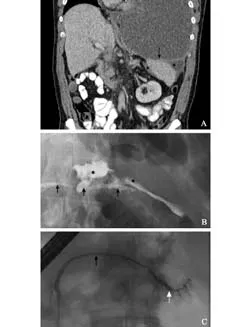

The site of duct disruption was the neck in 3, body in 4 and tail in 4 patients. The site of disruption was identified using CT imaging in 6 patients, with MRI imaging in 4, and at ERCP in 1. The left pleural cavity was the site of thoracic fluid collection in 8 patients, the posterior mediastinum in 2 and a single patient had bilateral pleural collections. Six fistulae passed via the aortic hiatus and 5 through the diaphragm. Fig. illustrates typical radiological features of PPF.

Treatment

Percutaneous intercostal drainage was performed in 9 cases (total of 16 drainage procedures).

Fig. Case demonstration of management of PPF. At initial presentation with shortness of breath a large left-sided pleural effusion was identified with mediastinal shift (A); percutaneous drainage treated the pleural collection and shortness of breath. Peri-splenic fluid is seen (*) and communicates with the pleural cavity via the diaphragm (arrow). At ERCP the pancreatic duct is seen (black arrows B and C) and site of duct disruption (white arrow) at initial presentation with peripancreatic collections of fluid (*) (B). After placement of a pancreatic duct stent the duct disruption healed and no leak was seen on subsequent pancreatography (C).

Endoscopic insertion of a pancreatic duct stent was attempted in 6 and placed in 5 patients. In 4 cases the pancreatic duct stent was inserted to treat ongoing loss of pancreatic secretions via the intercostal drain; in the fourth case the stent was inserted to drain a mediastinal collection not amenable to percutaneous drainage. The pancreatic duct stent was seen to pass from the pancreas into the posterior mediastinum via duct disruption located at the neck of the gland. In all five cases, PPF/mediastinal collection was resolved after pancreatic duct placement.

Three patients required surgery for refractory infection after the development of an empyema. One open thoracotomy with rib resection and one thoracoscopic decortication were performed. The final patient underwent left thoracotomy washout and formal closure of the diaphragmatic fistula track.

Follow-up and complications

The median duration of follow-up was 50 months (range 15-62). The thoracic fluid collections and fistulae have been successfully treated in 10 patients. None of these patients developed signs or symptoms of recurrent PPF. A small mediastinal collection was identified on follow-up imaging in 1 patient, however no treatment was instituted as the patient was asymptomatic.

No complications occurred in relation to intercostal drain insertion, endoscopic placement of a pancreatic duct stent, or surgery. In 1 patient, it was not possible to place an endoscopic pancreatic duct stent, however, the PPF settled regardless.

Discussion

This paper reviews the long-term follow-up of patients with PPF treated at a specialist pancreatic unit. Following successful resolution of PPF no patient developed a recurrence. Resolution of PPF was associated with diverse treatment modalities. The choice of treatment was dictated by the risk of intervention to the patient, the success of previous treatment, the site of duct disruption, progress of resolution of fistula output, and assessment of the patient's inflammatory/septic burden. Percutaneous drainage was performed in every patient with pleural fluid. Subsequent surgery was required in 3 of these patients for ongoing sepsis. pancreatic duct stenting proved useful and aided fistula resolution on every occasion it was successfully performed. The selection of patients to receive endoscopic stenting was limited to those with ongoing intercostal drain fluid output without empyema, and to a patient with sepsis secondary to a mediastinal collection that was notamenable to percutaneous drainage.

Excluding the cases with complicating distal pancreatectomy, the site of pancreatic duct disruption was identified on cross-sectional imaging in 8 of 9 cases; ERCP identified the site in the final case. This is contrary to a recent worldwide review of 37 cases where ERCP had greater sensitivity than CT (79% vs 43%).[4]It is likely that advances in the fidelity of CT and MRI explain our findings and mirror the experience of others.[5]Our initial radiological investigation was a CT scan as this demonstrates pancreatic inflammation, necrosis and peripancreatic fluid collections permitting early intervention. CT scanning alone was able to identify the site of the fistula in the majority of cases. MRI was performed in every case as this permits higher resolution of the pancreatic duct and biliary tree, and enabled characterization of the fistula in several cases where CT could not.

Identifying ductal strictures and the site of disruption is key to managing these patients. The location of peripancreatic fluid collections can indicate the site of disruption.[6,7]In cases requiring surgical intervention, inadequate preoperative planning with failure to identify the site of disruption increases the failure rate of surgery,[8]though in our series this was not necessary. pancreatic duct stenting bypasses the pancreatic sphincter, thus decreasing the pressure within the pancreatic duct and permitting a low pressure route for pancreas drainage away from the fistula to facilitate fistula healing.[9-11]

Pancreatic fistulae are common following pancreatic surgery, and pseudocysts are relatively common after severe acute pancreatitis. Internal fistulae are much less common. Extension of pancreatic secretions into the thorax occurs via the aortic hiatus or directly through the diaphragm.[12]Given the position of the aorta at this point, to the left of the spine, most collections fistulate into the left pleural cavity. Both patients who developed a PPF after pancreatectomy did so after first developing a left subphrenic collection complicating the development of a pancreatic fistula. After initially successful treatment, both patients represented with signs of sepsis and were found to have a left pleural effusion. Presumably splenectomy and mobilization of the lesser sac aided fistulation into the left hemithorax in these cases. The two patients with mediastinal collections who were included in the present study did not strictly have PPF. They were included as there was clear radiological evidence that the collection was due to a pancreatic fistula and that mediastinal fluid collections occur prior to fistulation into the pleural cavity and thus represent part of the same disease process. It is interesting to note that these 2 patients were relatively well, only one requiring intervention. Presumably this reflects the extent of disease whereby extensive fluid collections are more likely to fistulate into the pleural cavity. In our previous study, 4 of 6 patients had features of chronic pancreatitis on initial CT imaging, leading us to conclude that this was a risk factor for PPF,[3]in keeping with the experience of others.[2]None of the additional patients included in the present series had features of chronic pancreatitis and it seems reasonable to reconsider the potential role of chronic pancreatitis in the development of PPF. Some series originate from India where tropical pancreatitis is responsible for a high proportion of cases and partly explains the correlation with chronic pancreatitis.[9,10]To our knowledge, these are the first reports of PPF complicating pancreatectomy, and we present a high proportion of PPF complicating gallstone-induced pancreatitis.

Addressing the nutritional needs of these patients is essential to aid the resolution of the chronic sepsis that often exacerbates severe acute pancreatitis, and is also associated with the development of post-operative complications. The unit has a dedicated dietician who reviewed the metabolic requirements of patients and advised upon enteral and parenteral nutrition. We used the somatostatin analogue octreotide in all patients to suppress pancreatic exocrine function.[13]We favour post-pyloric feeding via nasojejunal feeding over total parenteral nutrition to avoid the risk of complications associated with parenteral feeding.[14]Given the presence of the pancreatic fistula and loss of pancreatic exocrine secretion away from the gastrointestinal tract, we enhanced digestion and gut function with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy[15-17](CREON®, 80 000 units TDS, Abbott Pharmaceuticals). At followup, the majority of patients (81.8%, 9/11) continue to receive oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation due to symptoms of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency.

In conclusion, PPFs are rare but do not just complicate chronic pancreatitis. Cross-sectional imaging identifies the anatomy of duct disruption and fistula track in most cases. Endoscopic therapy further defines pancreatic duct anatomy and permits placement of a pancreatic duct stent that treats the majority of cases refractory to percutaneous drainage alone. Surgery is indicated in cases of ongoing thoracic sepsis. Early enteral nutrition appears effective. Long-term success with this management is high.

Contributors:RKJ, MSG and SAM proposed the study. RKJ collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to the manuscript preparation. SAM is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Nathan H, Cameron JL, Choti MA, Schulick RD, Pawlik TM. The volume-outcomes effect in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery: hospital versus surgeon contributions and specificity of the relationship. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:528-538.

2 Ali T, Srinivasan N, Le V, Chimpiri AR, Tierney WM. Pancreaticopleural fistula. Pancreas 2009;38:e26-31.

3 Khan AZ, Ching R, Morris-Stiff G, England R, Sherridan MB, Smith AM. Pleuropancreatic fistulae: specialist center management. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:354-358.

4 Oh YS, Edmundowicz SA, Jonnalagadda SS, Azar RR. Pancreaticopleural fistula: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci 2006;51:1-6.

5 O'Toole D, Vullierme MP, Ponsot P, Maire F, Calmels V, Hentic O, et al. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic fistulae resulting in pancreatic ascites or pleural effusions in the era of helical CT and magnetic resonance imaging. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2007;31:686-693.

6 Nordback I, Sand J. The value of the endoscopic pancreatogram in peritoneal or pleural pancreatic fistula. Int Surg 1996;81:184-186.

7 Wakefield S, Tutty B, Britton J. Pancreaticopleural fistula: a rare complication of chronic pancreatitis. Postgrad Med J 1996;72:115-116.

8 Lipsett PA, Cameron JL. Internal pancreatic fistula. Am J Surg 1992;163:216-220.

9 Bhasin DK, Rana SS, Siyad I, Poddar U, Thapa BR, Sinha SK, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary nasopancreatic drainage alone to treat pancreatic ascites and pleural effusion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;21:1059-1064.

10 Pai CG, Suvarna D, Bhat G. Endoscopic treatment as firstline therapy for pancreatic ascites and pleural effusion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:1198-1202.

11 Kaman L, Behera A, Singh R, Katariya RN. Internal pancreatic fistulas with pancreatic ascites and pancreatic pleural effusions: recognition and management. ANZ J Surg 2001;71:221-225.

12 Ninos AP, Pierrakakis SK. Role of diaphragm in pancreaticopleural fistula. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17: 3759-3760.

13 Montorsi M, Zago M, Mosca F, Capussotti L, Zotti E, Ribotta G, et al. Efficacy of octreotide in the prevention of pancreatic fistula after elective pancreatic resections: a prospective, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Surgery 1995;117:26-31.

14 Al-Omran M, Albalawi ZH, Tashkandi MF, Al-Ansary LA. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition for acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(1):CD002837.

15 Ferrone M, Raimondo M, Scolapio JS. Pancreatic enzyme pharmacotherapy. Pharmacotherapy 2007;27:910-920.

16 Safdi M, Bekal PK, Martin S, Saeed ZA, Burton F, Toskes PP. The effects of oral pancreatic enzymes (Creon 10 capsule) on steatorrhea: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, parallel group trial in subjects with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 2006;33: 156-162.

17 Whitcomb DC, Lehman GA, Vasileva G, Malecka-Panas E, Gubergrits N, Shen Y, et al. Pancrelipase delayed-release capsules (CREON) for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency due to chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic surgery: A double-blind randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2276-2286.

Accepted after revision December 6, 2011

October 22, 2011

Author Affiliations: Department of Pancreatic Surgery, St James University Hospital, Leeds, UK (Roberts KJ, Sheridan M, Morris-Stiff G and Smith AM) Corresponding Author: Keith J Roberts, MD, Department of Pancreatic Surgery, St James University Hospital, Beckett St, Leeds, LS9 7TF, UK (Tel: 00447801658505; Email: j.k.roberts@bham.ac.uk)

Presented at the European Pancreatic Club, Magdeburg, Germany, June 2011 and at the Association of Upper GastroIntestinal Surgeons, Belfast, UK, September 2011.

© 2012, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60151-9

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Rapamycin combined with allogenic immature dendritic cells selectively expands CD4+CD25+Foxp3+regulatory T cells in rats

- Inhibition of 12-lipoxygenase reduces proliferation and induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo

- Prognostic significance and clinical relevance of Sprouty 2 protein expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma

- Management of hypersplenism in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: a surgical series

- The impact of family history of hepatocellular carcinoma on its patients' survival

- Percutaneous transhepatic portal catheterization guided by ultrasound technology for islet transplantation in rhesus monkey