Management of hypersplenism in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: a surgical series

2012-07-07RajeshRajalingamAmitJavedDharmanjaySharmaPujaSakhujaShivendraSinghHirdayaNagandAnilAgarwal

Rajesh Rajalingam, Amit Javed, Dharmanjay Sharma, Puja Sakhuja, Shivendra Singh, Hirdaya H Nag and Anil K Agarwal

New Delhi, India

Management of hypersplenism in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: a surgical series

Rajesh Rajalingam, Amit Javed, Dharmanjay Sharma, Puja Sakhuja, Shivendra Singh, Hirdaya H Nag and Anil K Agarwal

New Delhi, India

BACKGROUND:Hypersplenism is commonly seen in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH). While a splenectomy alone can effectively relieve the hypersplenism, it does not address the underlying portal hypertension. The present study was undertaken to analyze the impact of shunt and non-shunt operations on the resolution of hypersplenism in patients with NCPH. The relationship of symptomatic hypersplenism, severe hypersplenism and number of peripheral cell line defects to the severity of portal hypertension and outcome was also assessed.

METHODS:A retrospective analysis of NCPH patients with hypersplenism managed surgically between 1999 and 2009 at our center was done. Of 252 patients with NCPH, 64 (45 with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and 19 with non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis) had hypersplenism and constituted the study group. Statistical analysis was done using GraphPad InStat. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the chi-square test, ANOVA, and Student'sttest. The Mann-WhitneyUtest and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare non-parametric variables.

RESULTS:The mean age of patients in the study group was 21.81±6.1 years. Hypersplenism was symptomatic in 70.3% with an incidence of spontaneous bleeding at 26.5%, recurrent anemia at 34.4%, and recurrent infection at 29.7%. The mean duration of surgery was 4.16±1.9 hours, intraoperative blood loss was 457±126 (50-2000) mL, and postoperative hospital stay 5.5±1.9 days. Following surgery, normalization of hypersplenism occurred in all patients. On long-term followup, none of the patients developed hepatic encephalopathy and 4 had a variceal re-bleeding (2 after a splenectomy alone, 1each after an esophago-gastric devascularization and proximal splenorenal shunt). Patients with severe hypersplenism and those with defects in all three peripheral blood cell lineages were older, had a longer duration of symptoms, and a higher incidence of variceal bleeding and postoperative morbidity. In addition, patients with triple cell line defects had elevated portal pressure (P=0.001), portal biliopathy (P=0.02), portal gastropathy (P=0.005) and intraoperative blood loss (P=0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:Hypersplenism is effectively relieved by both shunt and non-shunt operations. A proximal splenorenal shunt not only relieves hypersplenism but also effectively addresses the potential complications of underlying portal hypertension and can be safely performed with good long-term outcome. Patients with hypersplenism who have defects in all three blood cell lineages have significantly elevated portal pressures and are at increased risk of complications of variceal bleeding, portal biliopathy and gastropathy.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2012;11:165-171)

portal hypertension; hypersplenism; splenorenal shunt; lienorenal shunt

Introduction

Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (NCPF) and extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) are two common causes of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) in India.[1,2]Most patients with NCPF are young, commonly present with variceal bleeding, and often have splenomegaly with hypersplenism. The decreased cell lines in peripheral blood makes these patients anemic, susceptible to infections (due to leukopenia) and spontaneous bleeding (due to thrombocytopenia).[3]Although there is an abundant literature describing the role of endoscopic therapy and surgery in the management of variceal bleeding, the literature on the incidence and management of hypersplenism in this group of patients is limited. While a splenectomy alone is sufficient for treating hypersplenism, it does not address the underlying portalhypertension, and other shunt or non-shunt operations are often required in these patients.[2]We operate on 20 to 25 NCPH patients every year. The aim of this study was to analyze the impact of shunt and nonshunt operations on the resolution of hypersplenism in patients with NCPH. The relationship of symptomatic hypersplenism, severe hypersplenism and number of peripheral cell line defects to the severity of portal hypertension and outcome was also assessed.

Methods

Study design

NCPH patients (EHPVO and NCPF) who had been managed surgically between 1999 and 2009 were analyzed retrospectively from a prospectively maintained portal hypertension database. All the patients underwent complete hemogram (including reticulocyte count and peripheral smear), liver function test, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and Doppler ultrasound of the abdomen. Magnetic resonance cholangiography was added in patients with suspected portal biliopathy. Esophageal varices were graded according to Conn's classification and gastric varices classified according to Sarin et al.[4,5]A diagnosis of NCPH was made according to clinical presentations, Doppler findings, and results of liver function tests. EHPVO was diagnosed by demonstration of main portal vein thrombosis with cavernomatous transformation. In doubtful cases of NCPF, a preoperative liver biopsy was made to rule out cirrhosis.

Patients with hypersplenism (both symptomatic and asymptomatic) were included in this analysis. Those with hypersplenism due to an underlying chronic liver disease or a non-cirrhotic etiology other than EHPVO and NCPF were excluded.

Definition and classification of hypersplenism

Hypersplenism was defined as the presence of splenomegaly with a defect in any one of the peripheral cell lines (anemia: hemoglobin <8 g/dL with normocytic and normochromic appearance on peripheral smear, leukocyte count of <3.5×109/L and a platelet count of <150×109/L).[6]Severe hypersplenism was defined as a leukocyte count of <2.0×109/L and a platelet count of <75× 109/L. The degree of splenomegaly was assessed using Hackett's classification.[7]Symptomatic hypersplenism was defined as requirement for repeated blood transfusions/symptoms of anemia (without an obvious cause), recurrent infections, or spontaneous bleeding episodes (such as epistaxis, gum bleed, or menorrhagia).

The indications for surgical treatment included variceal bleeding (most common), symptomatic hypersplenism, portal biliopathy, and growth retardation. The treatment included proximal splenorenal shunt (PSRS), esophagogastric devascularization (EGD), or splenectomy. In patients undergoing a shunt (after 2004), the portal pressure was measured intraoperatively (both pre- and post-shunt) by cannulating an omental vein.

Data analysis

We analyzed the clinical presentation of NCPH patients with hypersplenism and the effect of surgery (PSRS or EGD). Patients with symptomatic hypersplenism were compared to those without symptoms and the severity of hypersplenism (as indicated by severe hypersplenism and the number of cell line defects) was assessed as an indicator of persistent and severe portal hypertension.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using GraphPad InStat. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the chi-square test, ANOVA, and Student'sttest. The Mann-WhitneyUtest and Kruskal-Wallis test were used for comparing non-parametric variables.P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between 1999 and 2009, 252 patients with NCPH were treated surgically at our department. Of these, 64 (25.4%) had hypersplenism. The cause of hypersplenism was EHPVO in 45 patients and NCPF in 19. The mean age of the patients was 21.81±6.1 years and 34 patients (53.1%) were male. In most of the patients, the hypersplenism was symptomatic (n=45, 70.3%) even though it was not the sole indication for surgery and the mean duration of symptoms was 6.78±3.1 years. The incidences of spontaneous bleeding, recurrent anemia, and recurrent infection were 26.5%, 34.4%, and 29.7% respectively. Fifty-three patients had variceal bleeding, 17 had symptomatic portal biliopathy, 4 had bleeding from ectopic varices, and 2 had significant growth retardation. On examination, all patients had an enlarged spleen (mild, 12; moderate, 19; and severe, 33).

Clinical data

The mean preoperative hematological parameters were hemoglobin 8.12±1.90 g/dL, total leukocyte count 3.87±0.97×109/L, and platelet count 89.02±17.56×109/L. Thirty-eight patients had a hemoglobin level of <8 g/dL,37 had a total leukocyte count of <3.5×109/L, and 52 had a platelet count of <150×109/L. Eighteen patients had triple, 33 had double, and 13 had single cell-line defects.

At the time of surgery, esophageal varices were present in 60 patients (21 grade I, 17 grade II, 9 grade III, and 13 grade IV) with completely eradicated varices in 4. Thirty (of these 60) patients had gastro-esophageal varices (23 Gastro-oeophageal varices typei(GOV I), 7 GOV II). In addition, portal hypertensive gastropathy was present in 28 patients and 6 had ectopic varices (isolated gastric in 3, colon in 2, and rectum in 1). Most (60.9%) of the patients had undergone at least one session of endoscopic therapy in the past and were referred for surgical treatment due to either failure of endoscopic treatment or lack of compliance.

Indications and surgical treatment

The primary indications of surgery in these patients were upper gastrointestinal bleeding in 50 (gastrointestinal bleeding with symptomatic hypersplenism in 19, with asymptomatic hypersplenism in 14, with portal biliopathy/ growth retardation and asymptomatic or symptomatic hypersplenism in 17) and symptomatic hypersplenism in 14 (7 with spontaneous bleeding, 7 with recurrent infection, and 5 with recurrent anemia).

The most common surgery was PSRS (in 55 patients). In 2 patients splenectomy was done alone. In the early study period, EGD procedure with splenectomy was performed in 7 patients (5 in emergency and 2 in an elective setting). The mean duration of surgery was 4.16± 1.9 hours and the estimated mean intraoperative blood loss was 457±126 (50-2000) mL. Peri-operative blood transfusion was needed in 16 patients. The mean postshunt portal pressure was 26.2±4.2 cmH2O.

Complications

The most common postoperative complication was fever (15 patients). In 1 patient this was due to cholangitis (due to underlying portal biliopathy) and was treated with nasobiliary drainage and injectable antibiotics. Ten patients developed wound infection, which was a little more common in those who had undergone preoperative endoscopic biliary stenting for portal biliopathy. Four patients had chest infection and 3 had transient ascites. Intra-abdominal bleeding manifested by high-volume hemorrhagic output from the drain developed in 2 patients. One patient was treated conservatively and the other required re-exploration and ligation of a bleeding omental vessel. One patient, operated in emergency, died in the postoperative period because of a fulminant chest infection. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 5.5± 1.9 days.

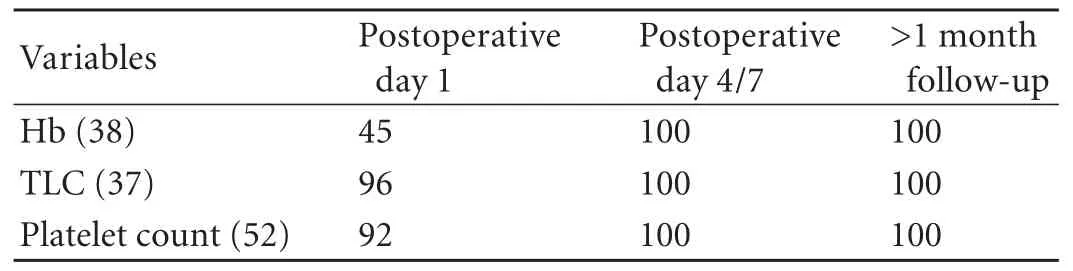

Table 1. Normalization of hypersplenic cell lines in the postoperative period (%)

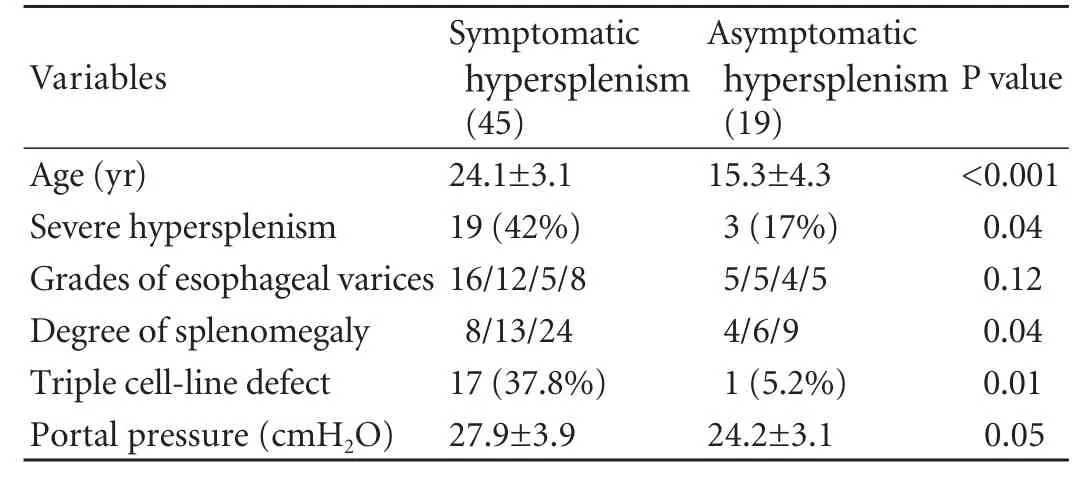

Table 2. Significance of symptomatic hypersplenism

Outcome

The hematological parameters normalized immediately after surgery in most patients but within 1 week of surgery in all patients (Table 1). The mean postoperative hemoglobin level was 9.7±0.9 g/dL, total leukocyte count 11.62±1.21×109/L, and platelet count 305.21±85.4×109/L.

Fifty-five patients (PSRS 48 patients, splenectomy 2, and EGD 5) were followed up for more than 3 years. In 42 patients, a patent shunt was documented by followup Doppler ultrasound and another 5 had indirect evidence to suggest a patent shunt (non-visualized shunt but a dilated left renal vein with a decrease in the grade of esophageal varices). Four had variceal rebleeding (2 following splenectomy alone, 1 after EGD, and 1 after PSRS). The patients with rebleeding were treated endoscopically. There was no incidence of post-shunt hepatic encephalopathy in any of the patients.

Implications of hypersplenism

Symptomatic hypersplenism

Comparing patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic hypersplenism found that those with symptomatic hypersplenism were older, had a higher incidence of severe hypersplenism, larger spleen, higher portal pressure and triple cell-line defects (Table 2).

Severe hypersplenism

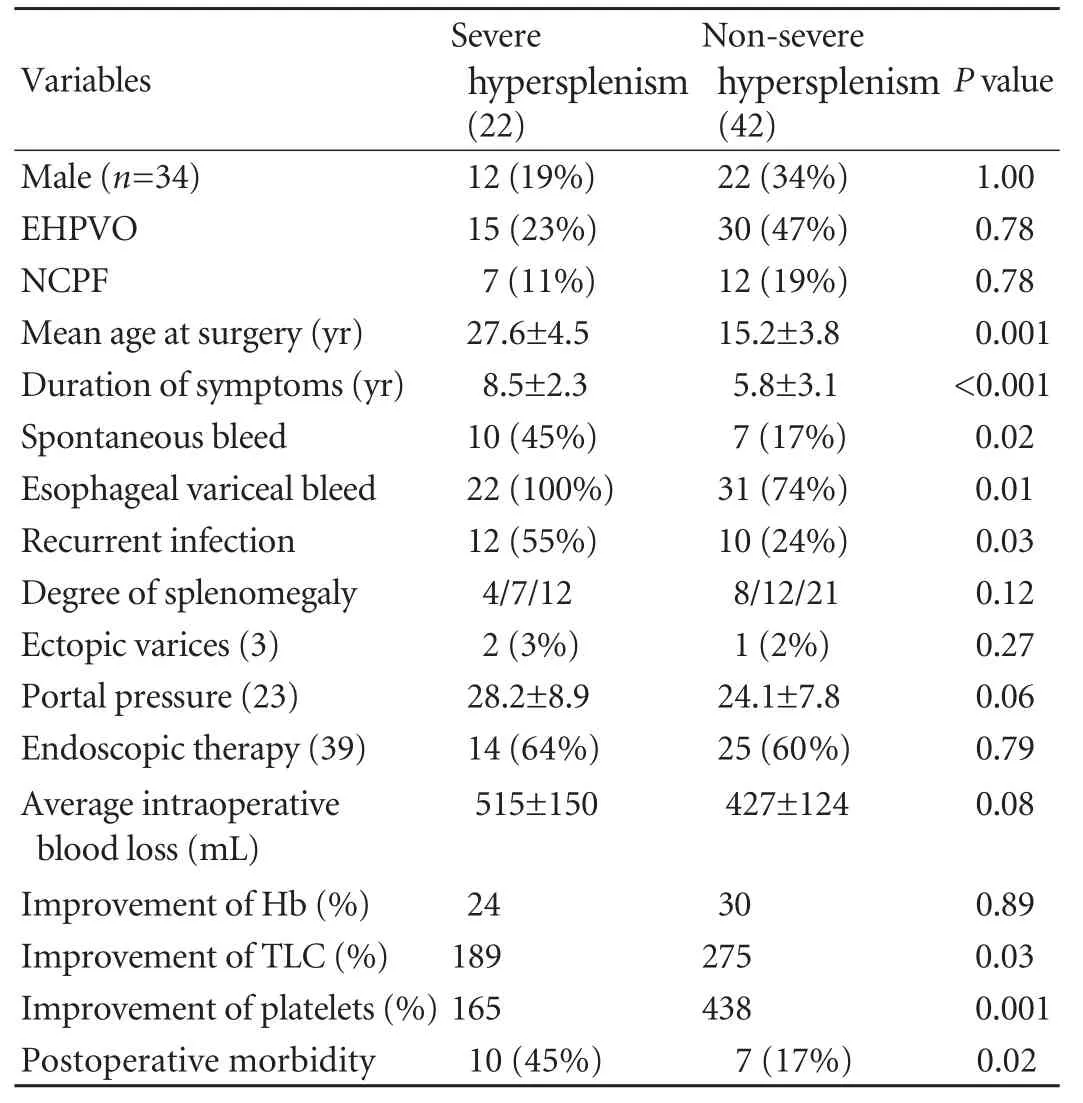

Of the 64 patients, 22 had severe hypersplenism. Compared with those without severe hypersplenism (42), these patients were older, were symptomaticfor a longer duration, had an increased incidence of spontaneous bleeding, higher incidences of esophageal variceal bleeding and recurrent infections, and a higher postoperative morbidity. The total leukocyte and platelet counts improved significantly in these patients (Table 3).

Table 3. Significance of severe hypersplenism

Number of cell-line defects

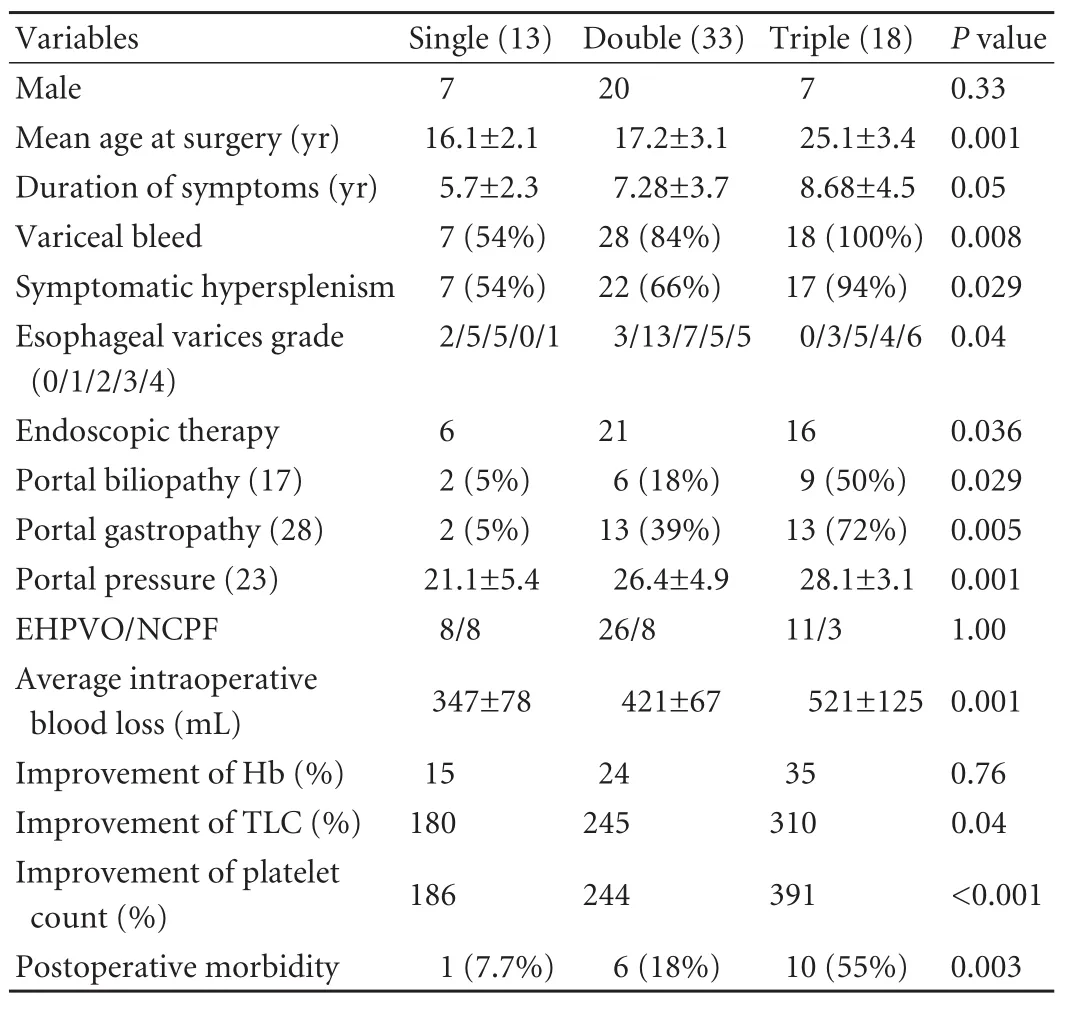

In an analysis to ascertain the correlation of the number of cell-line defects with the severity of portal hypertension, we found that patients with triple cellline defects (compared with those with defects in two or one cell lines) were older at the time of surgery, had a longer duration of symptoms, a higher grade of esophageal varices, a higher incidence of variceal bleeding, symptomatic hypersplenism, post-operative morbidity and a significant improvement in hematological parameters following surgery. In addition, patients with triple defects (compared to those with defects in two or one cell lines) had significantly elevated portal pressures, a higher incidence of portal biliopathy, portal gastropathy and intraoperative blood loss (Table 4).

Discussion

The term hypersplenism was first used by Chauffaud in 1907.[8]It is characterized by one or more cell-line defects in the peripheral blood smear in the presence of an enlarged spleen and a normal or a hypercellular bone marrow, which resolves with splenectomy.[6]Although bone marrow biopsy is indicated when malignant, infiltrative and infectious causes (like leukemia, Gaucher's disease and systemic tuberculosis) need to be excluded, its diagnosis in patients with portal hypertension can be made on the basis of clinical and hematological parameters alone.[9]

Table 4. Significance in number of cell-line defects

Secondary hypersplenism occurs in patients with portal hypertension due to both cirrhotic and noncirrhotic etiology. Its incidence in patients with chronic liver disease has been reported to range from 2% to 61% in different series.[10]These patients exhibit varying degrees of anemia, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia has been shown to correlate with the severity of liver disease and has been used as a prognostic marker in these patients.[11]In contrast, hypersplenism is much more common in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and may be more severe due to the presence of a larger spleen in these patients.[12]The reported incidence varies from 22% to as high as 80%.[13,14]In the present series, the incidence was 25.4%. In most patients, hypersplenism is asymptomatic.[14]This is in contrast to the current series wherein a significant proportion (70%) of patients with hypersplenism had symptoms. This high incidence could be explained by the fact that ours was a surgical series and many of the patients had failed to benefit from previous medical therapy. There is no report on the clinical manifestations of hypersplenism in such patients and we found that recurrent anemia requiring blood transfusions is the most common manifestation(34.3%) followed by recurrent infections (most commonly chest infections; 29.9%) and spontaneous bleeding episodes (26.6%).

There has been considerable speculation over the mechanism by which enlargement of the spleen causes reduction in the cell counts in peripheral blood. In a study of 218 patients with Gaucher's disease, Gielchinsky et al[15]found a significant correlation between the degree of splenomegaly and the cell counts. A large spleen may concentrate the blood cells to a disproportionate degree and this may be due to an increased blood flow consequent to an increased cardiac output in patients with portal hypertension.[16,17]The other mechanisms proposed include decreased production of hepatic thrombopoietic factors, immunological mechanisms, intravascular activation and increased consumption of platelets in the diseased liver.[18]Patients with EHPVO and NCPF have larger spleens (as compared to cirrhotics) and the pooling and sequestration of blood within the enlarged spleen may lead to a depression of cell counts.[19]This correlation is, however, poor in some instances.[20]In the present study, even though the patients with larger spleens had a significantly higher incidence of symptomatic hypersplenism, the size of the spleen was not associated with its severity. This implies that, apart from sequestration and destruction of blood in the spleen, other factors may also be involved. Mild compensated disseminated intravascular coagulation has been seen in a few patients with NCPH.[21]

Although performing a splenectomy alone would lead to the resolution of hypersplenism in both cirrhotics and non-cirrhotics, this does not address the underlying portal hypertension in these patients (NCPH), which requires either endoscopic treatment (for ablating esophageal varices) or surgical treatment to decompress the portal system.[22]In addition, splenectomy alone in these patients leads to thrombosis of the splenic vein, a possible route for a future shunt (if needed). Two patients in the present series underwent splenectomy alone and both had a variceal rebleeding during the follow-up, which necessitated multiple sessions of endoscopic variceal ablation. A PSRS is especially useful in these patients as, in addition to shunting the hypertensive portal system, the splenectomy done as a part of the procedure takes care of the hypersplenism. In the present study we did 55 PSRS and 9 splenectomies with or without esophagogastric devascularization. PSRS was performed wherever possible and most of the esophageal devascularization was done as an emergency procedure for acute variceal bleeding in the early part of our experience. In 2 patients, a planned PSRS could not be completed and these patients underwent a splenectomy alone. Following surgical treatment, thrombocytopenia and leucopenia normalized in most patients on day 1 with 100% resolution of hypersplenism by the time of discharge from the hospital. The average time to complete the shunt procedure was 260 minutes without significant morbidity and mortality and no incidence of post-shunt hepatic encephalopathy. Postshunt encephalopathy is uncommon in these patients as the underlying liver function is normal/near normal.

Various other options for hypersplenism in NCPH patients include side-to-side and distal splenorenal shunts, mesenteric-left portal shunt (Rex shunt) and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). Although they are effective for the management of variceal bleeding and hypersplenism, these procedure leave behind the large spleen, which often causes abdominal pain, discomfort, and risk of trauma, resulting in a poor quality of life in these young patients.[23]

Implications of hypersplenism in NCPH

Patients with symptomatic hypersplenism were older with a higher incidence of severe hypersplenism, higher portal pressure and triple cell-line defects. Though severe hypersplenism is an independent risk factor for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal bleeding, and death in cirrhotic patients,[10]its role in NCPH patients has not been evaluated. The incidence of severe hypersplenism in the present series was 34.3% and these patients were older, had a prolonged duration of symptoms, a higher incidence of symptomatic hypersplenism, esophageal variceal bleeding and postoperative morbidity. This can be explained by the fact that as NCPH patients grow older, natural portal-systemic collaterals open up and become more efficient in decompressing the portal bed, thereby reducing the incidence of bleeding.[24,25]However, the continually increasing flow of blood through the spleen causes the spleen to enlarge with worsening hypersplenism in about 50% of cases.[26]Also, the increased incidence of variceal bleeding in severe hypersplenism could be explained by the increased risk of infection which is postulated as one of the etiologies for variceal bleeding.[27]

Hypersplenism is considered to be one of the markers of persistent portal hypertension even after the eradication of varices. We hypothesized that the number of cell-line defects is an important indicator of persistent portal hypertension. We found that patients with triple cell-line defects were older and had a prolonged duration of symptoms, a high grade of varices and symptomatic hypersplenism. They also had an increased incidence of portal gastropathy, high portal pressure and portal biliopathy. These findings suggest that triplecell-line defects may be a simple and effective predictor of persistent portal hypertension and an indication for early and definitive surgical intervention. Postoperative morbidity correlated well with severe hypersplenism and triple defects which showed increased infectious complications in these patients, due to defective cell lines.

In conclusion, although hypersplenism in patients with NCPH can be treated by splenectomy alone, patients with a normal liver are best managed by PSRS. While splenectomy alone would relieve hypersplenism, the risk of potential complications of variceal bleeding would remain. Moreover, following splenectomy, the splenic vein becomes thrombosed, precluding a subsequent PSRS (if needed). PSRS not only relieves hypersplenism in these patients but also decompresses portal hypertension, thereby preventing potential complications of variceal bleeding and the need for regular endoscopy for variceal ablation. In addition, it removes the large spleen (which can be a significant cause of morbidity) and can be performed successfully in the majority of patients with an acceptable morbidity. While we had excellent results with PSRS, especially in managing hypersplenism in patients with NCPH and large spleen size, other shunts may be equally effective for smaller spleens or other etiologies of NCPH. Patients with defects in all three blood cell lineages have significantly elevated portal pressures and are at increased risk of complications of variceal bleeding, portal biliopathy and gastropathy.

Contributors:AAK conceptualized and proposed the study. RR and SD collected and analyzed the data. RR and JA wrote the first draft. All histopathology of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension was done by SP, critical evaluation was done by JA, SS, NHH and AAK. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. AAK is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Sarin SK, Kapoor D. Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis: current concepts and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17: 526-534.

2 Sarin SK, Agarwal SR. Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Semin Liver Dis 2002;22:43-58.

3 Sigalet DL. Biliary tract disorders and portal hypertension. In: Ashcraft KW, Pediatric surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2000:580-596.

4 Conn HO. Ammonia tolerance in the diagnosis of esophageal varices. A comparison of endoscopic, radiologic, and biochemical techniques. J Lab Clin Med 1967;70:442-451.

5 Sarin SK, Kumar A. Gastric varices: profile, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;84:1244-1249.

6 Liangpunsakul S, Ulmer BJ, Chalasani N. Predictors and implications of severe hypersplenism in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Med Sci 2003;326:111-116.

7 Ogilvie C, Evans C. Splenomegaly. In: Ogilvie C, Evans C. Chamberlaine's symptoms and signs in clinical medicine. 11th edition. Brucks, Butterworth;1987:490.

8 Chauffaud M. Apropos de la communication de M Vaquez. Bulletins et Memoires de la Societe Medicale des Hopitaux de Paris 1907;24:1201-1203.

9 Peck-Radosavljevic M. Hypersplenism. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;13:317-323.

10 Bashour FN, Teran JC, Mullen KD. Prevalence of peripheral blood cytopenias (hypersplenism) in patients with nonalcoholic chronic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:2936-2939.

11 Yanaga K, Tzakis AG, Shimada M, Campbell WE, Marsh JW, Stieber AC, et al. Reversal of hypersplenism following orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg 1989;210:180-183.

12 Mehta S, Gondal R, Saxena S, Sarin SK. Profile of hypersplenism in cirrhosis and non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Hepatology 1994;20:A217.

13 Orloff MJ, Orloff MS, Girard B, Orloff SL. Bleeding esophagogastric varices from extrahepatic portal hypertension: 40 years' experience with portal-systemic shunt. J Am Coll Surg 2002;194:717-730.

14 Mitra SK, Kumar V, Datta DV, Rao PN, Sandhu K, Singh GK, et al. Extrahepatic portal hypertension: a review of 70 cases. J Pediatr Surg 1978;13:51-57.

15 Gielchinsky Y, Elstein D, Hadas-Halpern I, Lahad A, Abrahamov A, Zimran A. Is there a correlation between degree of splenomegaly, symptoms and hypersplenism? A study of 218 patients with Gaucher disease. Br J Haematol 1999;106:812-816.

16 Aster RH. Pooling of platelets in the spleen: role in the pathogenesis of "hypersplenic" thrombocytopenia. J Clin Invest 1966;45:645-657.

17 Kaplan ME, Jandl JH. The effect of rheumatoid factors and of antigobulins of immune hemolysis in vivo. J Exp Med 1963;117:105-125.

18 Jørgensen B, Fischer E, Ingeberg S, Hollaender N, Ring-Larsen H, Henriksen JH. Decreased blood platelet volume and count in patients with liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1984;19:492-496.

19 Penny R, Rozenberg MC, Firkin BG. The splenic platelet pool. Blood 1966;27:1-16.

20 Sharma BC, Singh RP, Chawla YK, Narasimhan KL, Rao KL, Mitra SK, et al. Effect of shunt surgery on spleen size, portal pressure and oesophageal varices in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997; 12:582-584.

21 Bajaj JS, Bhattacharjee J, Sarin SK. Coagulation profile and platelet function in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;16:641-646.

22 Sarin SK, Sollano JD, Chawla YK, Amarapurkar D, Hamid S, Hashizume M, et al. Consensus on extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction. Liver Int 2006;26:512-519.

23 Krishna YR, Yachha SK, Srivastava A, Negi D, Lal R, Poddar U. Quality of life in children managed for extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2010;50: 531-536.

24 Boles ET Jr, Wise WE Jr, Birken G. Extrahepatic portal hypertension in children. Long-term evaluation. Am J Surg 1986;151:734-739.

25 Dilawari JB, Raju GS, Chawla YK. Development of large spleno-adreno-renal shunt after endoscopic sclerotherapy. Gastroenterology 1989;97:421-426.

26 Fonkalsrud EW, Myers NA, Robinson MJ. Management of extrahepatic portal hypertension in children. Ann Surg 1974; 180:487-493.

27 Goulis J, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Bacterial infection in the pathogenesis of variceal bleeding. Lancet 1999;353:139-142.

Accepted after revision December 1, 2011

Your future is only as bright as your mind is open.

—Rich Wilkins

July 8, 2011

Author Affiliations: Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery (Rajalingam R, Javed A, Sharma D, Singh S, Nag HH and Agarwal AK) and Department of Pathology (Sakhuja P), G. B. Pant Hospital and Maulana Azad Medical College, Delhi University, New Delhi, India

Anil K Agarwal, MCh, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Room 223, Academic Block, 2nd Floor, G. B. Pant Hospital, New Delhi 110002, India (Tel: 91-11-23235702; Fax: 91-11-23235702; Email: aka.gis@gmail.com)

© 2012, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60143-X

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Pancreaticopleural fistula: etiology, treatment and long-term follow-up

- Rapamycin combined with allogenic immature dendritic cells selectively expands CD4+CD25+Foxp3+regulatory T cells in rats

- Inhibition of 12-lipoxygenase reduces proliferation and induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo

- Prognostic significance and clinical relevance of Sprouty 2 protein expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma

- The impact of family history of hepatocellular carcinoma on its patients' survival

- Percutaneous transhepatic portal catheterization guided by ultrasound technology for islet transplantation in rhesus monkey