The impact of family history of hepatocellular carcinoma on its patients' survival

2012-07-07WingChiuDaiSheungTatFanTanToCheungKennethSHChokAlbertCYChanSimonHYTsangRonnieTPPoonandChungMauLo

Wing Chiu Dai, Sheung Tat Fan, Tan To Cheung, Kenneth SH Chok, Albert CY Chan, Simon HY Tsang, Ronnie TP Poon and Chung Mau Lo

Hong Kong, China

Original Article / Liver

The impact of family history of hepatocellular carcinoma on its patients' survival

Wing Chiu Dai, Sheung Tat Fan, Tan To Cheung, Kenneth SH Chok, Albert CY Chan, Simon HY Tsang, Ronnie TP Poon and Chung Mau Lo

Hong Kong, China

BACKGROUND:Family history of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been identified as a risk factor for the development of the disease. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of such a history on HCC patients' survival.

METHODS:Data of all HCC patients (n=4532) managed at our center from 1989 to 2008 were prospectively collected. The patients were quizzed on their various characteristics including family HCC history.

RESULTS:Totally 475 (10.48%) patients had a family history of HCC. They presented the disease at a significantly earlier age (median 53 vs 59 years,P<0.0001) and at an earlier stage (the United Network for Organ Sharing staging system). They had significantly better liver function in terms of Child-Pugh classification and serum albumin and bilirubin levels. Significantly more of them presented the disease without symptoms (44.0% vs 29.4%,P<0.0001). They also had significantly better overall survival under these specifications: patients in the whole study cohort, patients who had minor hepatectomy, patients with stageidisease, patients with stage II disease, and patients with stage III disease.

CONCLUSIONS:Contrary to what is generally believed, we found in this study cohort that patients with a family history of HCC had better overall survival than those without such a history. We believe this was in part due to earlier diagnosis of the disease and better liver function in this group of patients. However, the effects of genetic factors on the risk of HCC cannot be overlooked and are yet to be identified.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2012;11:160-164)

hepatocellular carcinoma; family history; resection; survival; risk factor

Introduction

Chronic infections with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses are the most well-established environmental risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) worldwide.[1]Other risk factors that have been associated with HCC development include liver cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, aflatoxin exposure, and male sex.[2-8]Meanwhile, familial aggregation of liver cancer has been reported.[9-13]Dietary habits and other behaviors associated with HCC that cluster in families may account for some of the observed familial aggregation of the disease. Amongst studies of patients with chronic infection of hepatitis B virus, family history of HCC is also identified as a risk factor for the disease's development. Thus, genetic factors are likely to modify the risk of HCC.[14]In the literature, there are a few studies focusing on the familial risk of HCC, but the prognosis of HCC in this particular group of patients remains unclear.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective study drawing on prospectively collected data involving 4532 patients aged between 18 and 97 years who were diagnosed with HCC and were subsequently managed at our center from 1989 to 2008. Upon recruitment, each patient was personally interviewed to obtain information on their sociodemographic characteristics, habits of cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking, personal medical history, and family history of HCC. HCC was staged accordingto the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) staging system.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 15.0.1. Categorical data were presented as number and percentage and compared by the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test where appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation unless specified and compared by Student'sttest or the Mann-WhitneyUtest. Overall survival of patients was determined with the Kaplan-Meier method and life tables, and significance of survival differences was determined with the log-rank test.P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Participants' characteristics

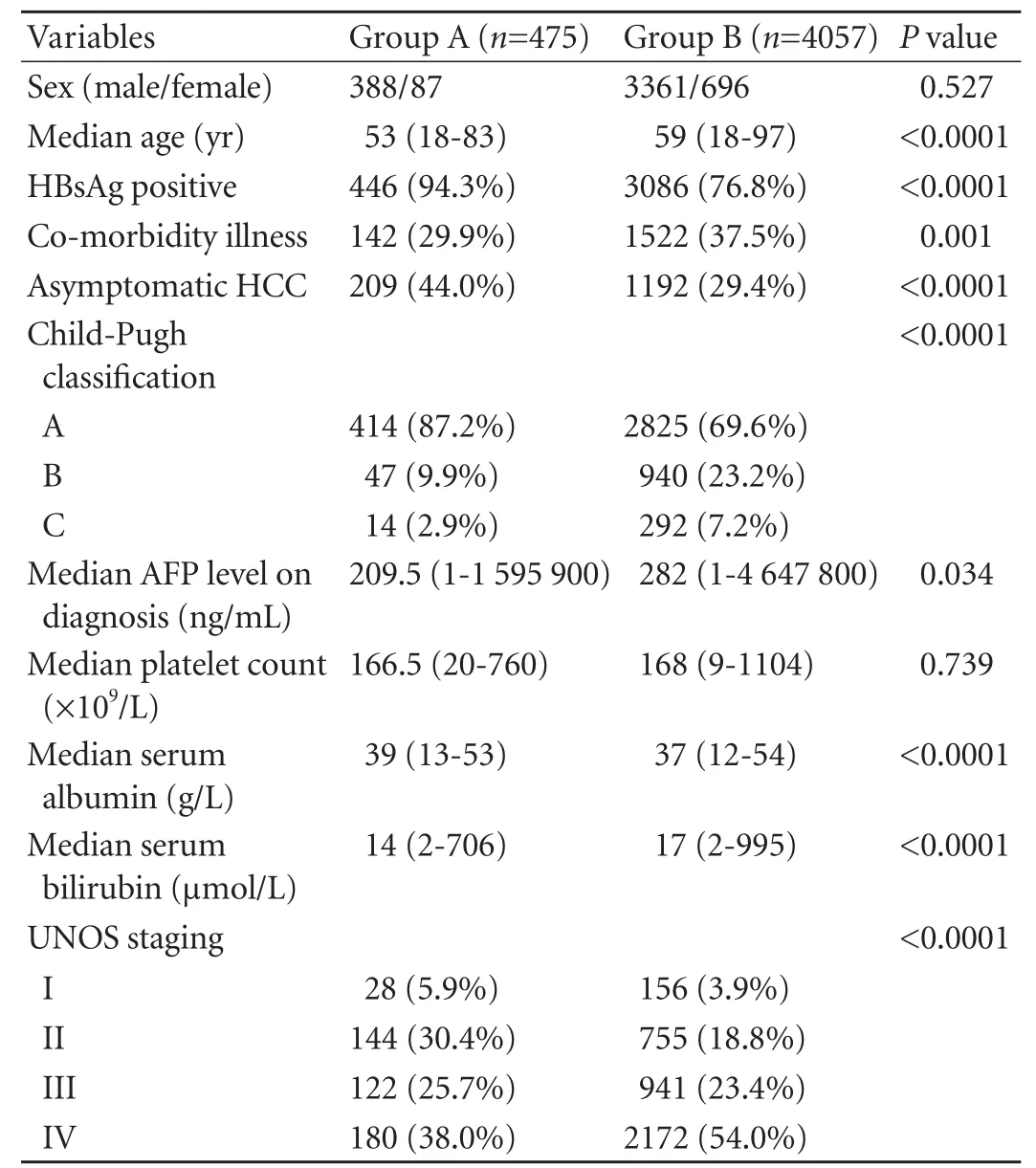

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 4532 patients in the study. Patients with a family historyof HCC (n=475, group A) (median age 53 years; range 18-83 years) were significantly younger than patients without such a history (n=4057, group B) (median age 59 years; range 18-97 years) (P<0.0001). Significantly more patients in group A were carriers of hepatitis B virus (94.3% vs 76.8%,P<0.0001) and were asymptomatic (44.0% vs 29.4%,P<0.0001). Group A patients had significantly better liver function in terms of Child-Pugh classification and serum albumin and bilirubin levels (all withP<0.0001). In group A, 5.9%, 30.4%, 25.7% and 38.0% of patients had stage I, II, III and IV HCC respectively. The corresponding percentages in group B were 3.9%, 18.8%, 23.4% and 54.0% (P<0.0001).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with and without a family history of HCC

Management

Overall survival

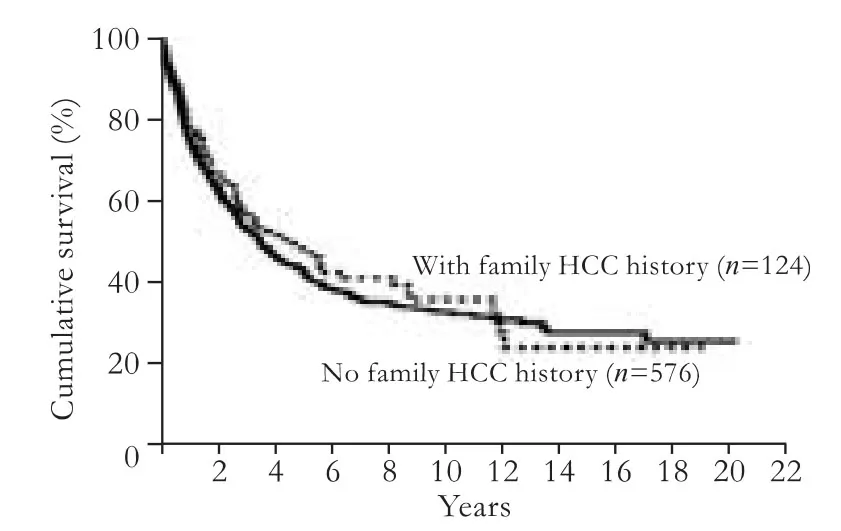

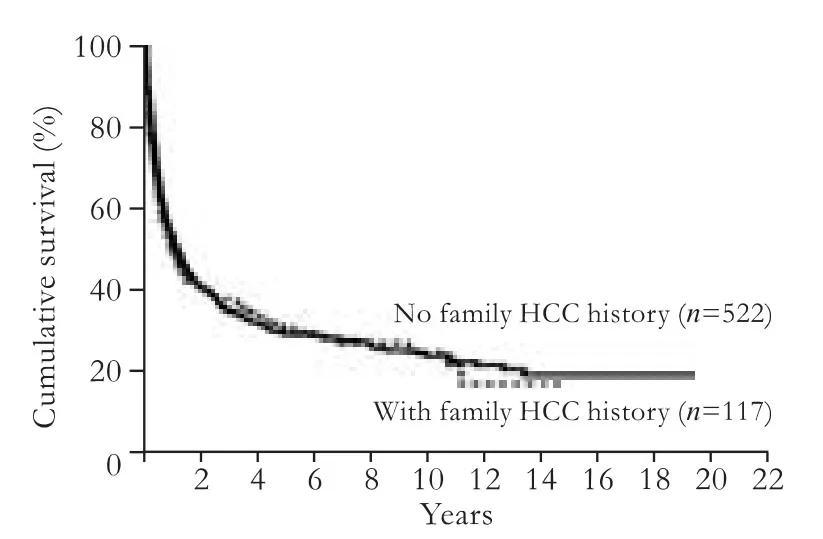

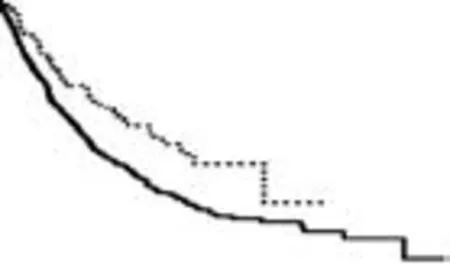

Group A had 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates of62.7%, 43.9% and 37.2%, respectively. Group B had the corresponding rates at 45.8%, 28.2% and 20.8% (Fig. 1). The median survival was 25.7 months for group A and 9.6 months for group B (P<0.0001).

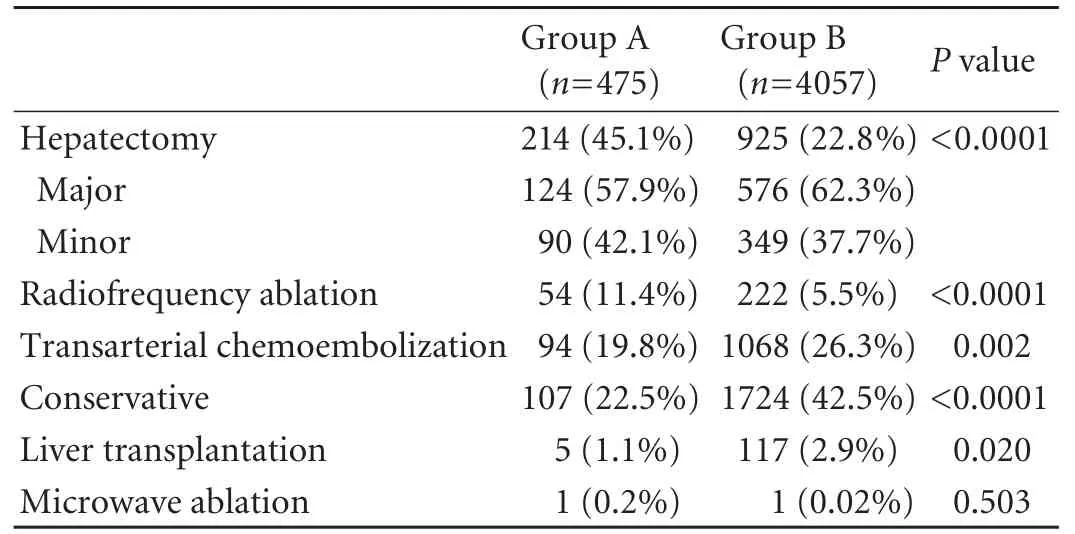

Table 2. Treatment modalities for patients with and without a family history of HCC

Fig. 1. Overall survival of all patients (P<0.0001).

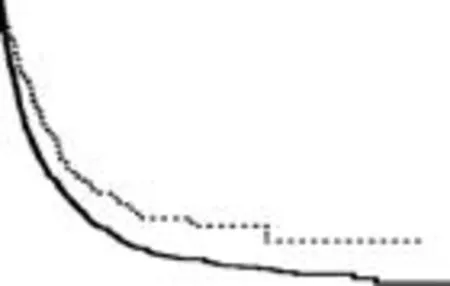

Fig. 2. Overall survival of patients with major hepatectomy (P=0.446).

Fig. 3. Disease-free survival of patients with major hepatectomy (P=0.748).

Fig. 4. Overall survival of patients with minor hepatectomy (P=0.013).

Fig. 5. Disease-free survival of patients with minor hepatectomy (P=0.463).

Altogether 700 patients underwent major hepatectomy. Among them, 124 were group A patients, and they had 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates of 78.8%, 57.3% and 48.3%, respectively. Group B patients (n=576) had the corresponding rates of 75.5%, 53.2% and 43% respectively (P=0.446) (Fig. 2). The two groups also showed no significant difference in disease-free survivals (P=0.748) (Fig. 3). Totally 439 patients underwent minor hepatectomy. The 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates were 93.2%, 78.5% and 72.2%, respectively for group A patients (n=90) and 89.4%, 71.2% and 57.1%, respectively for group B patients (n=349) (P=0.013) (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference in disease-free survival between the two groups (P=0.463) (Fig. 5).

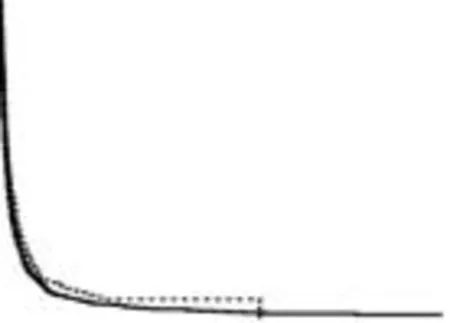

Fig. 6. Overall survival of patients with stageidisease (P=0.041).

Fig. 7. Overall survival of patients with stage II disease (P=0.002).

Fig. 8. Overall survival of patients with stage III disease (P=0.002).

Fig. 9. Overall survival of patients with stage IV disease (P=0.057).

We also analyzed the survival data according to the staging of disease (Figs. 6-9). For HCC at stages I, II and III, group A had a significantly better overall survival: stage I, 69.3 vs 130.5 months,P=0.041; stage II, 61.4 vs 105.4 months,P=0.002; stage III, 21.2 vs 33.0 months,P=0.002. However, for HCC at stage IV, the difference was not significant (4.5 vs 3.8 months,P=0.057).

Discussion

Hepatocarcinogenesis is a multi-step process that involves viral factors, host genetic factors, chemical carcinogens, and their interactions. The reported association between a family history of liver cancer and HCC could be explained by the clustering of infections of hepatitis B virus among members of the same family. However, genetic factors might also play an important role in the carcinogenesis of these familial HCCs. In the literature, there are no data regarding the survival of patients with a family history of HCC. This study compared the clinicopathological features and survival between patients with and without such a history.

It is without doubt that there are some differences in demographic characteristics between group A and group B and there were confounding factors in analysis. We did not have a patient surveillance program for HCC in Hong Kong, but it is probable that patients in group A, with their family history of HCC, represented a more health-conscious population. Disease stage and treatment modality were two most important prognostic factors for survival and this was why we had separate analyses on these two factors.

It was found that group A patients presented HCC at a significantly earlier age and at an earlier stage, and significantly more of them were asymptomatic. With earlier diagnosis of the disease, it is not surprising to find that more patients in this group were amenable to hepatectomy or radiofrequency ablation as the primary treatment. This may also translate into the better overall survival in this group, with a median survival of 25.7 months compared with 9.6 months in group B.

However, despite earlier diagnosis, amongst patients who received hepatectomy, still more than half in each group required major resection as the primary treatment, and the overall survival after major hepatectomy was comparable between the two groups. For minor hepatectomy, on the other hand, the overall survival was significantly better in group A. Probably this is because in group A there were more patients with asymptomatic or early-stage HCC which was more amenable to minor hepatectomy. As to disease-free survival, the extent of hepatectomy made no difference and the groups fared similar. This may reflect that the natural history and biology of the disease were not altered by presentation or treatment modality.

Most people would think that patients with a family history of HCC would have a worse prognosis of the disease than those without such a history. In this study, on the contrary, it was found that when the stage of disease was considered, the former group of patients had significantly better survival than the latter group, except in the case of stage IV disease. This study is the first one in the literature to demonstrate such a phenomenon. This phenomenon cannot be totally attributable to earlier diagnosis as patients with the same stage of disease were compared.

As with all studies dealing with a family history of cancer, this study is not immune from recall bias, but since our data were collected prospectively, the bias effect in the two groups would be more or less equivalent. Further studies into this particular group of patients with a family history involving tumor biology and genetic analysis should be warranted.

Contributors:DWC designed the study, did the statistics, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. FST was responsible for the design of the study and critical revision and approval of the manuscript. CTT, CKSH, CACY and TSHY collected the data. PRTP and LCM were responsible for critical revision and approval of the manuscript.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Donato F, Boffetta P, Puoti M. A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies on the combined effect of hepatitis B and C virus infections in causing hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 1998;75:347-354.

2 Yu MC, Yuan JM. Environmental factors and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004;127:S72-78.

3 Beasley RP. Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 1988;61:1942-1956.

4 Yu MW, Tsai SF, Hsu KH, You SL, Lee SS, Chen CJ. Epidemiologic characteristics of malignant neoplasms in Taiwan: II. Liver cancer. J Natl Public Health Ass ROC 1988; 8:125-138.

5 Yu MW, Chen CJ. Hepatitis B and C viruses in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1994;17:71-91.

6 Yu MW, Hsu FC, Sheen IS, Chu CM, Lin DY, Chen CJ, et al. Prospective study of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:1039-1047.

7 Ross RK, Yuan JM, Yu MC, Wogan GN, Qian GS, Tu JT, et al. Urinary aflatoxin biomarkers and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 1992;339:943-946.

8 Yu MC, Tong MJ, Govindarajan S, Henderson BE. Nonviral risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in a low-risk population, the non-Asians of Los Angeles County, California. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991;83:1820-1826.

9 Demir G, Belentepe S, Ozguroglu M, Celik AF, Sayhan N, Tekin S, et al. Simultaneous presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma in identical twin brothers. Med Oncol 2002;19: 113-116.

10 Cai RL, Meng W, Lu HY, Lin WY, Jiang F, Shen FM. Segregation analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma in a moderately highincidence area of East China. World J Gastroenterol 2003;9: 2428-2432.

11 Zhang JY, Wang X, Han SG, Zhuang H. A case-control study of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in Henan, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:947-951.

12 Sun Z, Lu P, Gail MH, Pee D, Zhang Q, Ming L, et al. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in male hepatitis B surface antigen carriers with chronic hepatitis who have detectable urinary aflatoxin metabolite M1. Hepatology 1999; 30:379-383.

13 Yu MW, Chang HC, Liaw YF, Lin SM, Lee SD, Liu CJ, et al. Familial risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among chronic hepatitis B carriers and their relatives. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1159-1164.

14 Kim YJ, Lee HS. Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Intervirology 2005;48:10-15.

Received December 19, 2011

Accepted after revision February 15, 2012

ntly more patients in group B

transarterial chemoembolization (26.3% vs 19.8%) or conservative treatment (42.5% vs 22.5%) as palliation. On the other hand, significantly more patients in group A underwent hepatectomy (45.1% vs 22.8%) or radiofrequency ablation (11.4% vs 5.5%) as curative treatment (P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Author Affiliations: Department of Surgery (Dai WC, Fan ST, Cheung TT, Chok KSH, Chan ACY, Tsang SHY, Poon RTP and Lo CM); State Key Laboratory for Liver Research (Fan ST, Poon RTP and Lo CM), The University of Hong Kong, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China

Prof. Sheung Tat Fan, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China (Tel: 852-22554703; Fax: 852-29865262; Email: stfan@hku.hk)

© 2012, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60142-8

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Pancreaticopleural fistula: etiology, treatment and long-term follow-up

- Rapamycin combined with allogenic immature dendritic cells selectively expands CD4+CD25+Foxp3+regulatory T cells in rats

- Inhibition of 12-lipoxygenase reduces proliferation and induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo

- Prognostic significance and clinical relevance of Sprouty 2 protein expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma

- Management of hypersplenism in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: a surgical series

- Percutaneous transhepatic portal catheterization guided by ultrasound technology for islet transplantation in rhesus monkey