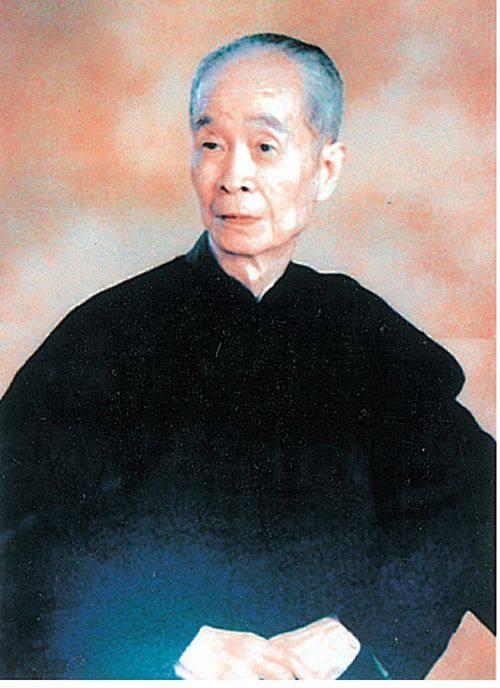

徐邦达:当代鉴定史上的风华绝唱

2012-04-29唐吟方

唐吟方

一年前,就听说徐邦达先生已卧床不起,日常生活需要护士照料,有人去看他,只能用眼神示意。人生百年,明知道迟早会有的事,但不愿听到的消息还是传来了,徐先生走了。

徐邦达和谢稚柳、启功、刘九庵、杨仁恺被称为中国古代书画鉴定界的“五老”。徐邦达历经百年风云最后一个归于道山,他的去世结束了一个传奇式的鉴定时代。外界听到的净是这个瘦小老头的传奇。早先台北媒体称其为“徐半尺”,国内有些媒体嫌不过瘾,更加激进,竟以“半寸”称之,对于这些江湖称法,徐邦达一笑了之。

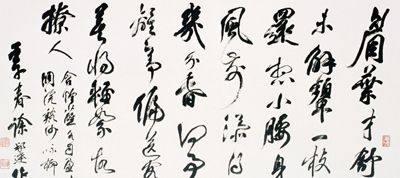

关于徐邦达,值得说的太多了。人们把他奉为鉴定大师,他自己则说专家也有错的时候。他嗜古书画如命,从十几岁开始买古画,九十多岁还在追买。他爱惜人才,生生把一个铁路工人培养成故宫研究员。他又是个标准的江浙男人,浪漫,懂得情调,一场黄昏恋,爱得执著缠绵,深情痴心,惹得他的友人、同为鉴定大家的启功善意地调笑“书妙诗新画有情”。

新世纪初南京的一位学者撰文评点当世的鉴定家,提出启功是学术鉴定,谢稚柳是艺术鉴定,徐邦达是技术鉴定。启功偏重文献,善长于用文献论证是不争的事实,正像谢稚柳从书画家性格去讨论古书画的真伪,在特定的时段能解决许多问题。所谓的类型划分,也只是指示一个鉴定家的学术偏向,不代表这个鉴定家的全部。说徐邦达是“技术鉴定”当然没错,他重视古书画家的传承、家世、交游等文献考据,1983年上海人民美术出版社出过他的《历代书画家传记考辨》。徐老也相当重视古书画本身的问题,如笔墨、风格、阶段性特点等内证,同样注重诸如装裱、书画材料等古书画外证,1981年北京文物出版社出的《古书画鉴定概论》就是这方面思考与实践的结果。以徐邦达对古书画鉴定的见解,出发点还是综合判断,决非技术两字所能包涵。以他与谢稚柳关于五代徐熙《雪竹图》之争为例。谢稚柳依据文献记载、对“落墨”的理解及阐述,认为落墨法符合徐熙画风体制,从而认定《雪竹图》是徐熙的作品。这里遇到个问题:《雪竹图》只是孤例,除此之外徐熙并无作品传世,文献的描述事实上无法代替图像的作用。徐邦达否定《雪竹图》的关键,除了对“落墨”有不同理解外,还在于对五代用绢形制的认定,当时画绢的门面一般不超过60厘米,属于窄幅,这虽非本证,但材料的时代性是确凿的,皮之不存,毛将焉附,由此推定这件作品无法归在徐熙的名下。这桩当代鉴定界有名的公案,因为徐和谢是当世并驾齐名的两大家,最后并无定论,但谢稚柳留下了一句话:“徐先生‘不迷信旧说,却迷信于绢,以绢来评定画的时代,这说明绘画不可认识的了,要认识只得靠绢。”徐邦达因此落下“技术鉴定”的名声。

其实,徐邦达是典型的“南风北渐”鉴定家。这样讲是1950年之前他生活在上海,有30多年的上海经历。他早期的鉴定方法继承了南派鉴定家的传统,虽然年纪轻轻,已在上海滩卓有名声,时贤认为徐邦达、张珩是当时中国东南一带最出色的两位鉴定家。吴湖帆出身名门,收藏众多,又以善鉴闻名,但也非常看好张、徐的才能,遇到难题,总要叫上张、徐,听听他们的看法。所以当新中国的文博事业刚刚起步,主持国家文物口工作的郑振铎,首先想到张珩,把他请到北京,张珩又把徐邦达介绍给郑振铎,从此,这两位从上海过来的鉴定家效力于北京故宫博物院,合力打造故宫新的“石渠宝笈”。他们经常往返于外地与北京琉璃厂之间,踏访全国百分之八十以上的县城。据徐邦达回忆:“跟张珩两个人,一天可以收几十件甚至上百件东西。”广泛征集,悉心查访,短短几年时间,便收集到无数件古书画珍品。后来徐邦达到故宫带了三千多件精品,故宫绘画馆藏品初具规模。资历老一点的故宫人至今大概还有印象,保管部记载古书画最原始的存档卡片还是徐邦达一点一笔用蝇头小楷写成的。

徐邦达在紫禁城的漫长工作经历,适逢其时,新中国建立后根据文化建设的需要,通过政令调集各地精品晋京,徐邦达还能经常到各地巡访,阅遍古今书画,如果再加上文革后参加五人鉴定小组全国巡鉴,他寓目的古书画数量,超过了历史上任何一位鉴定家,这使得他能从更宏观的角度把握古书画的源流,总结出鉴定中出现的一般性和特殊性规律。按徐邦達的鉴定风格而言,其本质是对考古学原理的合理借鉴吸收应用,仍然是图像比对与文献考据印证相结合的方法。徐邦达90岁时,王世襄写的贺联“心识五朝书画”,大约就是他鉴画生涯的真实写照。启功赋诗称其为“法眼燃犀鉴定家”,把徐邦达比作唐代的张彦远。同行一致认为徐邦达是当今鉴定界的巨眼。

1962年美术史家金维诺邀请张珩和徐邦达给中央美院美术史系学生讲课。张珩那本由讲课稿整理而成的《怎样鉴定书画》,实际上就是鉴定界“南风北渐”的初步总结,可惜张珩早逝。文革期间徐邦达也着手进行鉴定学概论撰述,他所做的工作完善并丰富深化了“南风北渐”体系的学科化。

对于“技术鉴定”的说法,徐邦达并不认可。古书画流传过程中的情况复杂,“技术”有时候无法解决面对古书画遇到的所有问题,这就要求一个鉴定家临机制宜,采取不一样的方法去应对。2001年笔者采访徐先生,这位阅画无数的“巨眼”说起鉴定,也有无奈:“有些东西我认为是真的,苦于无法求证,就不敢同外面讲。”他打了一个比方,大家都熟悉自己父亲的脚步声,只要是这种脚步声,你就听得出来。若有人问你为什么?你一定答不上来。这是一种感觉,感觉的判断说不清原因,但不是假的。很明显,系统概念下的徐邦达,他的思维里还有另一种鉴定方法。

相对于专业,生活中的徐邦达单纯。晚年名满天下的他即使不出门,裤兜里总要揣上几百块钱。有人问他为什么?他说一个男人身上哪能不带钱。他爱穿中装,中装是故乡海宁的一个师傅缝制的。徐邦达也把这个师傅介绍给友人王季迁、朱家溍。师傅出身草根,却有雅根,给老先生们制衣从来不收钱,只要求以字画代替。徐先生称这是“画衣”。他还喜欢享用美食。笔者曾与他同桌用餐,九十高龄的徐先生一盏鱼翅下肚后,连吃数个猪爪子,口腹之壮,真是不同寻常。

暮年的徐邦达赶上经济开放,拍卖市场兴起,他执锤敲响嘉德第一锤。那时拍卖市场风生水起,常常有好东西浮出水面。经徐邦达建议,故宫先后从拍卖会买进诸如宋人《十咏图》,石涛《高呼与可》、隋人《出师颂》、沈周临黄公望《富春山居图》等名迹,更多的名迹则无缘于博物馆。每当这个时候,徐邦达心急如焚,动员民间力量收藏,不让珍宝外流。他自己也去拍卖会,后来的许多古书画就以这样的方式流进了徐家,去年徐先生百岁寿辰,徐夫人曾拿出来在保利大厦展出,宋元明清珍墨荟萃,让人赞叹,让人心惊。

历史机遇加上个人的天赋才华,还有勤奋努力,成就了当代古书画鉴定界的一代巨擘。百年风华只造就了一个徐邦达。徐先生走了,留下了煌煌六百万字著作,留下了他满身书生意气的纯粹与坦诚,还有他的绵绵不绝的佳话和绝代风华。□

101岁的一代大师离我们而去,中国古代书画鉴定界的“国宝”,永远闭上了双眼。

徐邦达,1911年生于上海,祖籍浙江海宁。曾为故宫博物院研究员、国家文物鉴定委员会常务委员,西泠印社顾问。徐邦达集鉴定家、收藏家、书法家、画家、诗人、词家于一身,雅号“徐半尺”。2003年,他将一生创作的部分书画精品捐给故乡海宁,成立“徐邦达艺术馆”。他曾多次出访欧美,考察流失海外的中国书画,并与国外专家进行学术交流;徐邦达在两岸文化交流中发挥了重要的学术影响,在世界范围内赢得了同行的尊崇。

Masters Authentic Life

By Tang Yinfang

Master Xu Bangda (1911-2012) passed away on February 23, 2012 at the age of 101 years. The masters long life can roughly be divided into two periods. Before he was 50 years old, he was partly known as a preeminent artist. His artistry can be testified by a whopping price of 9.7 million for an artwork of his sold at an auction held by Poly Auction Group in June 2011. In his second 50 years, the master was largely known as a great authenticator.

Xu Bangda is one of the Big Five authenticators of modern China. The other four are Xie Zhiliu, Qigong, Liu Jiuan, and Yang Renkai. He was the last of the five and his demise puts an end to a legendary era of the great authenticators. There are many tales about his authenticating ancient paintings.

Xu had a lifelong passion for ancient paintings. He began to pur-chase ancient masterpieces when he was not yet 20 years old. His buying experience lasted well into his ninth decade.

In the early 21st century, a scholar in Nanjing compared Xu Bangda and other authentication masters based on their distinct approaches. According to the scholar, Xie Zhiliu (1910-1997) ap-praised antiques artistically; Xus approach was largely technique-oriented; Qigong relied heavily on ancient records and books. However, Xu Bangda resorted to a full range of things in appraising antiques. He gave priority to historical records about art, life sto-ries and friendships of ancient painters and calligraphers. In 1983, Shanghai Peoples Art Press printed Xus studies of biographies of ancient masters. Xu paid special attention to details of masterpieces such as brushstrokes, ink shades, styles, characteristics of a certain period. Another part of his appraisal secrets was to take a look at details such as paper and ink materials and mounting techniques. Xu wrote a book on how to evaluate ancient books.

According to history, once upon a time Xie Zhiliu and Xu Bangda disagreed upon the authenticity of a painting. An interest-ing debate became heated between the two masters. They discussed whether a painting was really pained by Xu Xi of the Five Dynas-ties (907-960). Xie argued that it was authentic and his judgment was based on ancient literature and a comparison between ancient records and what was present in the painting. Part of Xus argument was that the silk on which the painting was made could not have been produced during the years of the Five Dynasties. His reason-ing was quite simple: silk weavers of that time did not make silk fabric more than 60 centimeters wide.

Xu Bangda was one of the appraisers who brought the appraising expertise and experience of the south to Beijing after the founding of New China in 1949. By 1950, he had lived in Shanghai more than 30 years. He and Zhang Heng (1915-1963) were the two best-known art appraisers in the southeastern China.

Zhang Heng and Xu Bangda came to Beijing in 1950 at the in-vitation of Zhen Zhenduo, the head of the national administration for cultural relics, to build a new collection for the National Palace Museum, whose major treasures had been shipped to Taiwan when Chiang Kai-shek fled to the island province in the late 1940s. The two masters traveled across the country. They visited more than 80% of the county capitals on the mainland, searching and buying antiques from private collectors and owners. Within a few years, a collection of more than 3,000 pieces was put together thanks to the two masters. Xu catalogued the whole collection and wrote all the cards. Many people remember his meticulous small-character hand-writing in all these cards.

Xu Bangda lived long enough to be, arguably, the greatest ap-praiser in the history of China in terms of the number of antiques he evaluated and appraised during his long career. He worked as an appraiser for the palace mu-seum for decades. This status gave him opportunities to see the best things from all over the country and visit interest-ing places across the country. After the Cultural Revolu-tion (1966-1976), he joined a five-member team to travel through China to view and review antiques. It is said that no one in China has seen more ancient calligraphic works and paintings than he did. It is widely agreed that Xu is “the biggest eye” of the appraisal industry of China in modern times.

Xu wrote books and papers that add up to more than 6 million characters. The two books mentioned above systematically relate his evaluation theories, expertise, and practice.

Xu Bangda himself did not embrace the label of technique-centered approach. He pointed out that as ancient artworks survived through a full range of situations, it would be erroneous to confine oneself to a single method. He said it was advisable to be flexible and open-minded in appraising. He admitted that sometimes he was not so sure about his judgment. He thought some artworks were au-thentic, but he kept his opinion to himself, for he understood that it would be troublesome to ask people to take him at his mere word.

In his evening years, the palace museum in Beijing bought some ancient masters paintings at his suggestion. Many masterpieces on the market, however, were beyond the financial means of the museum. Xu always urged Chinese collectors to be generous so that the cultural treasures would stay in China. He himself bought some ancient calligraphic scrolls and paintings. In 2011 his private collection of paintings and calligraphies by ancient masters were exhibited at Poly Tower in Beijing. □