The Legal Status of the Bering Strait

2011-02-18JoshuaOwens

Joshua Owens

The Legal Status of the Bering Strait

Joshua Owens*

The present essay aims to ascertain the legal status of the Bering Strait,specifically with regards to the regime of straits used for international navigation.After consulting relevant sources of international law,primarily the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,this essay concludes that the Bering Strait should be considered a strait used for international navigation where passers-through enjoy the right of transit passage;the legal stances of the two littoral states-Russia and America-will also be discussed.Due to the geopolitical stature that the Strait will likely attain as Arctic navigation increases,it is preferable that a clear and fair system of administration be established in the Strait;therefore,the present essay makes recommendations on how to do so in accordance with international law and cognizant of the management techniques already being implemented in other international straits.

Bering Strait;Straits Used for International Navigation;Transit Passage

Ⅰ.Introduction

Of all the Straits in the Arctic,the Bering is among the narrowest and perhaps the most important.Though up till now it has not been the source of nearly as much contention as the Northwest and Northeast Passages,it,unlike those two,cannot possibly be detoured around.In other words,closing the Strait would effectively shut down vessel passage from the Bering Sea to the Arctic Ocean in a single stroke.Like the Malacca Straits in the South Pacific,the Bering Strait is a natural choke point in a crucial location.If it is possible to preventively resolve the associated legal issues concerning sovereignty and passage rights for foreign vessels prior to the onset of high-volume commercial navigation in this area,then much progress will already be made toward averting unnecessary conflict and tensions there in the future.

The Bering Strait,located between Russia’s easternmost continental protrusion and the westernmost one of the United States,is a narrow marine channel that connects the northern Pacific Ocean to the Arctic waters.The fact that this is one of very few Arctic outlets has,up to the present,not presented a major global issue,in light of the paucity of maritime traffic that has historically gone through.①See discussion below in sec.Ⅱ(B).Yet as the flurry of recent academic articles and news reports will confirm,interest in the Arctic,particularly in exploitation of its resources, both living and non-living,and in the use of its shipping lanes,has been on the rise congruent with the retreat of the Arctic ice sheet.②An attempt at presenting an exhaustive list would be unnecessarily cumbersome,but for an idea of recently-published academic pieces on the subject,see Angelle C.Smith,Frozen Assets:Ownership of Arctic Mineral Rights Must be Resolved to Prevent the Really Cold War,George Washington International Law Review,Vol.41,2010,p.651;Aldo Chircop, The Growth of International Shipping in the Arctic:Is a Regulatory Review Timely?,The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law,Vol.24,No.2,2009,p.355;Michael Byers,Who Owns the Arctic?Understanding Sovereignty Disputes in the North,Vancouver:Douglas&McIntyre Publishers INC,2009;Roger Howard,The Arctic Gold Rush:The New Race for Tomorrow’s Natural Resources,London:Continuum International Publishing Group,2009.The most important of these lanes no doubt comprise the Northeast and Northwest Passages,which are under claims of sovereignty by Russia and Canada,respectively.The formidable question of these passages’legal status is yet to be satisfactorily resolved,and it is outside the scope of this paper to attempt to do so.The humble Bering Strait,however,is likely to constitute a portion of voyages traversing either passage.③See Figure 1.See also E.J.Molenaar,Arctic Marine Shipping:Overview of the International Legal Framework,Gaps,and Options,Journal of Transnational Law&Policy, Vol.18,2009,p.293(remarking that“all trans-Arctic marine shipping must pass through the Bering Strait”).Therefore it is submitted that a study on the legal status of the Bering Strait,analysis of its potential for geopolitical significance,including discussion and suggestions on environmental protection and coastal Statemanagement would be of some practical use.①The present essay will analyze global issues from a realist perspective,taking account of

The following sections contain some relevant background information regarding law of the sea and particulars on the Bering Strait(sectionⅡ),examination of the legal postures of the two littoral States mentioned above(sectionⅢ),and some suggestions for the prudent,conflict-free administration of the Strait in the future(section IV).

Ⅱ.The Bering Strait and International Law of the Sea

In order to better understand the relevance of the Bering Strait in commercial navigation and international dealings,this section will begin a legal analysis with a look at the Strait’s geographical conditions and constraints,as well as their implications under international maritime law,notably that contained within the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea(hereinafter“UNCLOS”).②

A.Geographical Considerations and their Legal Implications

The Bering Strait measures,from the Asian to North American continental landmasses,roughly 53 miles(85 km,45 nm)across from Cape Dezhnev, the fact that,unless the international zeitgeist for development,sustainable or otherwise,is drastically altered soon,the demand for resources will push implacably toward large-scale exploitation of the Arctic,including mining,shipping,fishing,touring and other such commercial activities.One hopes that as access increases,the proper environmental protections will be enacted and enforced with an equivalent fervor through appropriate national legislation and international fora.For an alarming warning on the dangers posed by reckless development in the Arctic,see Andrew Van Wagner,It’s Getting Hot in Here,So Take Away all the Arctic’s Resources:A Look at a Melting Arctic and the Hot Competition for its Resources,Villanova Environmental Law Journal,Vol.21,2010,p.189.It should be noted that Donald Rothwell’s insightful presentation Arctic Choke Points and the Law of the Sea,Australian National University—ANU College of Law Research Paper No.10-81,2010 has broken ground on the analysis of the Bering Strait as it relates to law of the sea;however due to the comprehensive nature of that paper’s topic,it still seems worthwhile to delve further into circumstances pertaining specifically to the Bering Strait.

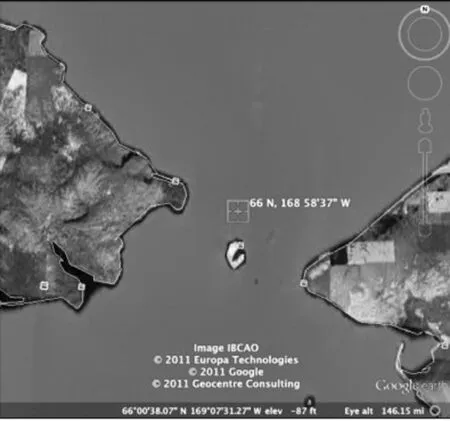

②United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Treaties and Agreements:Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea(done at Montego Bay),opened for signature December 10,1982,UN Doc.A/Conf.62/122,16 Nov 1994;reprinted at Internationa Legal Materials,Vol.21,p.1261 and U.N.T.S.,No.1833,p.397[hereinafter UNCLOS].Russia to Cape Prince of Wales,Alaska,with average depths of 30-50 meters.①World Atlas,Bering Strait,at http://www.worldatlas.com/aatlas/infopage/bering.htm, 11 October 2011.In the Arctic Council’s 2009 Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment,it is observed that“[a]t the strait’s narrowest point,the continents of North America and Asia are just 90 km apart.”Arctic Council 2009,Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report,Arctic Council,Norwegian Chairmanship,Oslo,Norway,190 pp,at http://www. arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about/documents/category/62-pame?download= 245:the-amsa-2009-report,p.106,30 November 2011.Close to the center of the Strait are Big and Little Diomede Islands,between which lies the US-Russian international boundary.②This boundary was reaffirmed in the Agreement between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Maritime Boundary,1 June 1990,International Legal Materials,Vol.29,p.941(hereinafter 1990 US-Soviet Boundary Agreement).See map 1.1990 US-Soviet Boundary Agreement,Art.2(1)states:“From the initial point,65°30′N.,168°58′37″W.,the maritime boundary extends north along the 168°58′37″W.meridian through the Bering Strait and Chukchi Sea into the Arctic Ocean as far as permitted under international law.”In effect,the boundary line runs neatly between the two Diomedes,as shown in map 2.For the Senate document including the text of the agreement as well as the US Senate’s advice and approval thereof,see Senate Treaty Document 101-22,at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/125431.pdf,11 October 2011.This agreement has not been ratified by the Russian Duma.These two small islands lie some 4 km apart.

At the Strait’s narrowest,the proximity of the two Capes leaves no room for high seas or exclusive economic zones(EEZs),both of which would offer potential passers-through ample freedoms of navigation.③See UNCLOS,Arts.58(1),87(1).Indeed,the waters directly between Little Diomede Island(US)and Cape Prince of Wales comprise a swath of only territorial sea.④See map 2 and accompanying explanation.Under international law,territorial seas are areas over which coastal States enjoy complete sovereignty,⑤See UNCLOS,Art.2.with the caveat that other States’vessels enjoy the right of innocent passage through them.⑥See UNCLOS,Art.17 reads:“Subject to this Convention,ships of all States,whether coastal or land-locked,enjoy the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea.”Concerning the meaning of the term“innocent passage”,UNCLOS stipulates that passage must be“continuous and expeditious”⑦See UNCLOS,Arts.18.and“not prejudicial to the peace,good order or security of the coastal State.”⑧See UNCLOS,Art.19(1).Article 19(2) enumerates several activities which may be considered non-innocent,including but not limited to weapons exercises,fishing,willful pollution and launching orlanding of aircraft.①Interestingly,this article does not state whether the list is exhaustive,leaving the possible interpretation that other acts may also be considered“prejudicial to the peace”of a coastal State.The focus of the present paper is on activities not in violation of innocent passage principles,such as commercial navigation of container ships,oil tankers or fishing vessels.

The Bering Strait does not,by mere virtue of containing territorial sea,automatically constitute a location that would attract much future maritime traffic.The following subheading will briefly assess the viability of establishing and maintaining shipping lanes through the Strait.

B.Ship ping Viability

As hinted at earlier,the Bering Strait could play an important role in maritime navigation routes.Merchant ships,warships,research and fishing vessels and others may all have an interest in passing through the Strait in the course of crossing either one of the Arctic(Northeast or Northwest)passages.To date,relatively little navigational activity has been taking place in the Arctic,②Take,for example,the fact that from 1903 to May 2010,only 135 voyages had gone through the Northwest Passage.Sixty of those voyages,nearly half,had taken place since 2000:this indicates a growing trend of willingness to brave the Arctic.Lawson W. Brigham,The Fast-Changing Maritime Arctic,Proceedings,May 2010,U.S.Naval Institute,Annapolis,Maryland,at https://www.princeton.edu/lisd/events/talks/brigham_ may2010.pdf,p.56,12 October 2011.See also 2009 Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment, pp.36~49(recounting the history of Arctic navigation).whose inclement and unpredictable weather coupled with forbidding ice have historically tended to deter investors and all but the hardiest explorers.③Nicholas Wapshott,Strife Looms between America,Canada over Route,N.Y.Sun,11 October 2007,at http://www.nysun.com/foreign/strife-looms-between-america-canada-over-route/64337/(stating that“[u]ntil now the passage has been icebound and immensely dangerous to navigate”),12 October 2011.On the other hand,2009 Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment,p.36,relates that navigation among indigenous peoples in the Arctic has been afoot since ancient times;at p.49 it points out that accumulating the necessary field data“may help to reduce the perceived risks of year-round marine transport in the Arctic,”which suggests that in the Arctic Council’s view,current obstacles to Arctic marine shipping are certainly not insurmountable.With the recent melt and the increased navigability it brings,though,potential Arcticplayers are beginning to rethink their positions.①Matt Roston,Note and Comment,The Northwest Passage’s Emergence as an International Highway,Southwestern Journal of International Law,Vol.15,2009,p.450(asserting the likelihood of Northwest Passage becoming a major navigational route following the ice melt);Roger Howard,The Arctic Gold Rush:The New Race for Tomorrow’s Natural Resources,London:Continuum International Publishing Group,2009,pp.109~110(stating that the distance of a Tokyo-London voyage could be reduced by 3,500 miles if using Arctic routes instead of the Suez Canal or as much as 5,500 if used instead of the Panama Canal;the author further relates that a Bremen-Shanghai voyage could be reduced by 3, 200 miles;in short,the distance of many such journeys would be cut by about a third).It is clear that the two Passages,both of which would presumably include a crossing of the Bering Strait,are economically viable or will be so in the future.In describing the Northeast Passage(often also referred to as the Northern Sea Route②Some sources use the two appellations“Northern Sea Route”(NSR)and“Northeast Passage”synonymously;more accurately,the two should be considered separate entities,the NSR constituting the center portion of the longer Northeast Passage.See Leonid Tymchenko,The Northern Sea Route:Russian Management and Jurisdiction over Navigation in Arctic Seas,in Alex G.Oude Elferink and Donald Rothwell ed.,The Law of the Sea and Polar Maritime Delimitation and Jurisdiction,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2001,pp.269~291.The present essay usually employs the term NSR because the discussion revolves around Russia’s legal stance concerning this route,which it regards as a domestic one.),one commentator notes the following:

The Northern Sea Route links the Barents Sea and the Bering Straits.When navigable,this route connecting Asia and Europe is three times faster than the alternative path through the Suez Canal.It could significantly reduce transportation time and costs between the Pacific Rim and Northern Europe and Eurasia.③Ariel Cohen,From Russian Competition to Natural Resources Access:Recasting U.S. Arctic Policy 2010,Backgrounder,No.2421,Heritage Foundation,at http://thf_media. s3.amazonaws.com/2010/pdf/bg2421.pdf,p.9,12 October 2011.

There are some complications associated with traversing the two northern passages,however.As to the Northern Sea Route(NSR),closely related to the sovereignty issue raised by the Russian Federation is Moscow’s policy of provi-ding mandatory icebreaker services to vessels transiting off Russian coasts.①Leonid Tymchenko,The Northern Sea Route:Russian Management and Jurisdiction over Navigation in Arctic Seas,in Alex G.Oude Elferink and Donald Rothwell ed.,The Law of the Sea and Polar Maritime Delimitation and Jurisdiction,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff Publishers,2001,pp.284~285.Another commentator notes:“Russia’s mandatory ice-breaker fees are high,and the fees are not directly linked to actual services rendered. For instance,during light summer ice conditions,an ice-strengthened vessel may be able to transit the NSR unescorted,but will still have to pay a full fee.The fee system is a major obstacle to transit traffic,and since the opening of the NSR to foreign vessels in 1991,the Russian authorities have yet to design a system that encourages the use of the route even under otherwise ideal conditions.”Claes Lykke Ragner,Den norra sjövägen,in Torsten Hallbeg ed.,Barents-ett gränsland i Norden,Stockholm:Arena Norden,2008,pp.114~127[English translation unpaginated,at http://www.fni.no/doc&pdf/clr-norden-nsr -en.pdf,16 October 2011.].The cost of these services can be prohibitive,②Claes Lykke Ragner,Den norra sjövägen,in Torsten Hallbeg ed.,Barents-ett gränsland i Norden,Stockholm:Arena Norden,2008,pp.114~127.though notably there have been reports of recent voyages being completed without the assistance of icebreakers;③Michael A.Becker,Russia and the Arctic:Opportunities for Engagement within the Existing Legal Framework Symposium:Russia and the Rule of Law:New Opportunities in Domestic and International Affairs,American University International Law Review,Vol. 25,2010,p.241(stating that in August 2009 two German-owned ships,the Beluga Fraternity and Beluga Foresight,“undertook and completed the voyage,with Russian approval and without ice-breaker assistance”).this points to a potential shift in Russia’s policy toward NSR navigators.④Leonid Tymchenko,The Northern Sea Route:Russian Management and Jurisdiction over Navigation in Arctic Seas,in Alex G.Oude Elferink and Donald Rothwell ed.,The Law of the Sea and Polar Maritime Delimitation and Jurisdiction,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff Publishers,2001,pp.286~288.Outlines a possible solution to problems posed by Russian administration of its NSR,namely internationalization of said passage,perhaps via an international NSR Convention.Likewise,a dispute exists over whether the Northwest Passage lies within Canada’s internal waters or comprises a strait used for international navigation.⑤See generally John Kennair,Conference:International Arctic Change and the Law and Politics of the Arctic Ocean Seabed,An Inconsistent Truth:Canadian Foreign Policy and the Northwest Passage,Vermont Law Review,Vol.34,2009,p.15;James Kraska,Symposium:Mounting Tension and Melting Ice:Exploring the Legal and Political Future of the Arctic,International Security and International Law in the Northwest Passage,Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law,Vol.42,2009,p.1109;Michael Byers and Suzanne Lalonde,Symposium:Mounting Tension and Melting Ice:Exploring the Legal and Political Future of the Arctic,Who Controls the Northwest Passage?,Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law,Vol.42,2009,p.1133.Such sources of uncertainty connected with the Arctic passages may dissuade some wary investors from making use of these routes.Much dis-cussion could be dedicated to the already considerable corpus treating the Russian and Canadian administration of their Arctic waters,claims to sovereignty and the responses from other States,but the constraints of this paper make it impossible.①For recent treatments of the subject concerning Canada’s position,see Rob Huebert,Canada and the Newly Emerging International Arctic Security Regime,in James Kraska ed., Arctic Security in an Age of Climate Change,New York:Cambridge University Press, 2011,p.193;Christopher Mark Macneill,Gaining Command and Control of the Northwest Passage:Strait Talk on Sovereignty,Transportation Law Journal,Vol.34,2007,p.355; Elizabeth Elliot-Meisel,Politics,Pride,and Precedent:The United States and Canada in the Northwest Passage,Ocean Development&International Law,Vol.4,2009,p.204;for a look at Russian policy and practice,in addition to the discussion below in sec.Ⅲ(a)of the present text,see also Betsy Baker,Symposium,Russia and the Rule of Law:New Opportunities in Domestic and International Affairs,Law,Science,and the Continental Shelf: Russia and the Promise of Arctic Cooperation,American University International Law Review,Vol.25,2010,p.251;R.Douglas Brubaker,The Russian Arctic Straits,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff,2005;David L.Vander Zwaag et al.,Governance of Arctic Marine Shipping,Dalhousie University Marine&Environmental Law Institute,10 October 2008,at http://arcticportal.org/uploads/bC/JU/bCJUa KAo52XTt HDZ359QNA/5.nov AMSA-Governance-of-Arctic-Marine-Shipping-Final-Report-1-Aug.pdf, pp.62~68,30 November 2011.Some foundational works on the subject include Donat Pharand,Canada’s Arctic Waters in International Law,New York:Cambridge University Press,1988 and Erik Franckx,Maritime Claims in the Arctic:Canadian and Russian Perspectives,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff,1993.

Apart from concerns about icebreaker costs and sovereignty,there are also poor weather conditions to consider.From a shipping perspective,isolation coupled with increased likelihood of weather-related accidents equals augmented risk.This is by no means insurmountable,as one commentator points out:“if shipping wants to use the Northeast Arctic passage,insurers will provide the necessary risk coverage.”②Rakish Suppiah,The Northeast Arctic Passage:possibilities and economic considerations, Mar Studies,Vol.32,2006;Maritime Studies,Vol.151,2006,unpaginated,at http:// www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MarStudies/2006/32.html,p.151,12 October 2011.Admittedly,Arctic passages are currently less agreeable routes in some aspects than the more traditional Suez or Panama Canal routes,yet one can imagine that in concert with future infrastructural improvements in the Arctic as well as multilateral agreements easing restrictions on navigators,there will arise an increased willingness to traverse the Arctic passages,especially from the private sector.The end result will be that the Bering Strait sees huge increases in maritime traffic,though growth is likely to be kept in check to some degree by environmental concerns.In that vein,the following subsections will discuss the applicability of UNCLOS’s straits used forinternational navigation(SUFINs)regime to the Bering Strait.

C.The Regime of Straits Used for International Navigation(SUFINs)

As has already been concluded,vessels passing through the Bering Strait shall enjoy no less than the right of innocent passage as defined in UNCLOS.①See UNCLOS,partⅡ,sec.3,subsec.A.Another important question remains:will the Strait be considered a strait used for international navigation(SUFIN)?This type of strait,governed by UNCLOS,②See UNCLOS,partⅢ.offers navigators the right of transit passage,a more hands-off regime than that of innocent passage.These two distinct passage regimes are to be implemented in two separate areas:transit passage,which is only to be enjoyed in SUFINs,and innocent passage,which is to be enjoyed in those areas of territorial sea not classified as SUFINs or in SUFINs where transit passage does not apply.③See UNCLOS,Art.45 and United Nations Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone,Art.16(4);see also Ana G.López Martín,International Straits:Concept, Classification and Rules of Passage,Madrid:Springer,2010,pp.109~149.The list of non-innocent activities that nullify any purported exercise of innocent passage is,as mentioned earlier,somewhat restrictive;④UNCLOS,Art.19(2).many of these conditions are not imposed on vessels or aircraft exercising the right of transit passage while navigating or overflying SUFINs.⑤R.R.Churchill and A.V.Lowe,The Law of the Sea,3rded.,Juris Publishing,Manchester University Press,1999,p.105.Regarding the regime of transit passage,Churchill and Lowe explain:“While there is no criterion of‘innocence’to be satisfied,ships and aircraft exercising this right are bound to refrain from the threat or use of force…[t]his is,however,not a condition of the right of transit passage but rather an obligation ancillary to it.”⑥R.R.Churchill and A.V.Lowe,The Law of the Sea,3rded.,Juris Publishing,Manchester University Press,1999,p.107(emphasis in original).In practical terms,this means that a strait State is not permitted to badger foreign ships exercising the right of transit passage along its coast to ensure those vessels“refrain from the threat or use of force”because such practices would detract substantially from the freedom of navigation originally intended for the transit passage regime.

Further,“any activity that is not an exercise of the right of transit passageremains subject to the‘other applicable provisions’of the Convention…[a] ccordingly,any activity threatening a coastal State would bring the ship or aircraft under the general regime of innocent passage,in which case passage could be denied for want of innocence.”①R.R.Churchill and A.V.Lowe,The Law of the Sea,3rded.,Juris Publishing,Manchester University Press,1999,p.107.In other words,only in the face of egregious provocation would a coastal State be justified in revoking the right of transit passage from passers-through.What exactly constitutes impermissible behavior when exercising the right of transit passage within SUFINs is fluidly defined and can depend on various factors including political and economic ones,therefore conflicts between navigators purportedly exercising their navigational rights and coastal States enforcing jurisdictional ones are not unlikely.②Such as the Corfu Channel case,discussed below;see also Mark Valencia,Policy Forum Online 08-013A:US Hypocrisy in the Strait of Hormuz?,12 February 2008,Nautilus Institute,unpaginated,at http://www.nautilus.org/publications/essays/napsnet/forum/ security/08013 Valencia.html,12 October 2011(analyzing the legal implications of certain Iran-US naval incidents that occurred in Iran’s territorial sea).

To highlight the main points of contrast between the regimes of innocent and transit passage:the exercise of transit passage may be enjoyed by aircraft as well as vessels,submarines may traverse SUFINs underwater,and the right of transit passage may not be suspended;the right of innocent passage over the territorial sea,on the other hand,is not granted to aircraft,submarines must navigate at the water’s surface with flag showing,and the right may be suspended by the coastal State under certain circumstances,③See UNCLOS,partⅡ,sec.3,subsec.A,UNCLOS partⅢand accompanying text.except in the case of SUFINs under the innocent passage regime.④UNCLOS,Art.45.In 1949 the International Court of Justice(ICJ)heard the Corfu Channel dispute,a precedential case for the definition of SUFINs under international law.⑤International Court of Justice Report,1949,p.4.The court’s ruling established a“quality over quantity”approach to identifying SUFINs,stating:

It may be asked whether the test is to be found in the volume of traffic passing through the Strait or in its greater or lesser im portance for international navigation.But in the opinion of the Court the decisive criterion is rather its geographical situation as connecting two parts of the high seas and the fact of its being used for international navigation.Norcan it be decisive that this Strait is not a necessary route between two parts of the high seas,but only an alternative passage between the Aegean and the Adriatic Seas.It has nevertheless been a useful route for international maritime traffic.①International Court of Justice Report,Rep.4,1949,p.28.

This description preserves a certain amount of subjectivity,or at least judicial discretion,in defining which straits do or do not qualify as SUFINs,such as the degree to which a strait is a“useful route for international maritime traffic.”Article 37 of UNCLOS provides that the SUFINs regime“applies to straits which are used for international navigation between one part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone and another part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone.”The Bering Strait meets this criterion,but notably, this article excludes certain straits that connect areas of high seas or EEZ only to a State’s territorial sea.②In contrast,the United Nations Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone,Art.16(4)provided:“There shall be no suspension of the innocent passage of foreign ships through straits which are used for international navigation between one part of the high seas and another part of the high seas or the territorial sea of a foreign State.”This arrangement was reached at the behest of Israel and its allies,in order to ensure free navigation to and from the port of Eilat.Wang Zelin,Research on the Legal Status of Arctic Passage,Doctoral Thesis,Xiamen University,2011(Ch.),p.13.UNCLOS,Art.45 upholds the principle that innocent passage may not be suspended in SUFINs which connect“a part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone and the territorial sea of a foreign State”.A few examples of SUFINs include the Straits of Gibraltar,Hormuz,Bab el Mandeb,Malacca and Dover.③R.R.Churchill and A.V.Lowe,The Law of the Sea,3rded.,Juris Publishing,Manchester University Press,1999,p.105.There exists no authoritative body to identify the world’s SUFINs,thus it would appear that the designation of a strait specifically as one used for international navigation is a political and diplomatic process just as much as a legal one;④For example,in 1971 Indonesia and Malaysia jointly declared that the Straits of Malacca were not“an international waterway”.Nadaisan Logaraj,Navigational Safety,Oil Pollution and Passage in the Straits of Malacca,Malaya Law Review,Vol.20,1978,p.288.what is more, such varied inputs as politics and diplomacy,the voice of the private sector,and even to some extent the law,are not static but constantly in flux.In the absence of an international court or tribunal’s judgment,the deciding factor is most likely to be international consensus,especially among the States with the highest interest in a particular strait.Naturally,the environmental and securityconcerns of riparian states often conflict with non-littoral States’navigational interests.It goes without saying that,as in the case of the two Arctic Passages,forging a workable balance between the opposing interests of coastal State jurisdiction and free navigation will not always be a smooth process,and consensus among the two camps may be difficult to achieve.With these factors in mind,we will now examine the Bering Strait in terms of its suitability to the SUFINs regime.

D.The Applicability of the SUFINs Regime to the Bering Strait

In seeking to define a geographical entity,it is important to take into account the intangible circumstances of the States involved in addition to bare cartographic or geological considerations.In the case of the Bering Strait,the two littoral States differ in one conspicuous regard:the US remains a non-Party to the UNCLOS,①As of August 2012.yet it considers the contents of the Convention regarding“traditional uses of the ocean”to be customary international law,②See President Ronald Reagan’s Statement on United States Ocean Policy,10 March 1983, International Legal Material s,Vol.22,1983,p.464;American Journal of International Law,Vol.77,1983,p.619.therefore it is bound to a certain extent despite lack of formal participation in the UNCLOS regime.③The US Dept.of State’s website recounts America’s track record vis-à-vis UNCLOS,at http://www.state.gov/g/oes/ocns/opa/convention/,15 October 2011.There exists no prohibition on designating a strait adjacent to a non-Party as a SUFIN,so America’s nonpartisanship should not play a major role in the process of determining the legal status of the Bering Strait;rather,it should be a decision reached through international discussion and consensus.

The Bering Strait is not currently a maritime superhighway,④Though according to Arctic Council 2009,Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report,Norwegian Chairmanship,Oslo,Norway,at http://www.arctic-council.org/index. php/en/about/documents/category/62-pame?download=245:the-amsa-2009-report,p.109,30 November 2011:“approximately 150 large commercial vessels pass through the Bering Strait during the July-October open water period,”excluding“fishing vessels,which are generally smaller,as well as fuel barges serving coastal mining activities and coastal communities.”See map 3 for an idea of traffic volume through the Bering Strait in recent years.but that does not automatically rule it out from ever being classified as a SUFIN.A judicious reading of UNCLOS provisions would not lead to an interpretation that a strait in question must have had SUFIN status at the time the UNCLOS waspromulgated in order to be considered as such at a later date;①UNCLOS,Art.37 states that the SUFIN status and accompanying right of transit passage“applies to straits which are used for international navigation between one part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone and another part of the high seas or an exclusive economic zone.”There is no chronological precondition mentioned here defining when international traffic must begin in a strait for it to be considered a SUFIN.on the contrary,it follows logically that even straits which in 1982 were not home to large volumes of international traffic could later be designated as SUFINs if and when international navigation does commence.Presumably,nationalistic or unilateral claims should not be an end-all barrier to the advent of international navigation in a given location.Therefore,taking note of the Bering Strait’s prime location and the likelihood of its increasing use in trans-Arctic voyages, the Strait ought to be considered a SUFIN under international law where navigators enjoy the right of transit passage.

Ⅲ.America’s and Russia’s Legal Postures

This section attempts to ascertain the two littoral States’legal positions regarding the classification of the Bering Strait as a SUFIN by analyzing relevant statements,policies or practices of the respective governments.

A.Russia

From the Russian perspective,it is difficult to consider the Bering Strait without taking note of its connectedness to the NSR,a traditionally domestic route.As Ariel Cohen explains:“The Russian Federation Arctic policy proclaims‘the use of the Northern Sea Route as a national unified transportation link of the Russian Federation in the Arctic’to be a national interest of Russia”[footnote omitted].②Ariel Cohen,From Russian Competition to Natural Resources Access:Recasting U.S. Arctic Policy 2010,Backgrounder,No.2421,Heritage Foundation,at http://thf_media. s3.amazonaws.com/2010/pdf/bg2421.pdf,p.9,12 October 2011.Furthermore,Russia’s current Arctic legal regime must be viewed within a historical context,one including the USSR government.③Erik Franckx,The Legal Regime of Navigation in the Russian Arctic,Journal of Transnational Law&Policy,Vol.18,2009,p.330(stating that“the current legal regime of Arctic marine shipping in the Northern Sea Route”is based on regulations dating back to 1990,a year before the USSR’s collapse).It is not within the scope of this paper to summarize the complete history of navi-gating the NSR,but a few main points may be reiterated about the current administration of Arctic waters under Russian jurisdiction.The following paragraphs attempt to outline Russia’s stance toward navigation through the Bering Strait by examining obligations both under international law and its own domestic legislation.

1.International Obligations

The Russian Federation,as a State Party to UNCLOS,is constrained to grant the right of innocent passage through its territorial sea to navigators; however due to article 234 of the UNCLOSspecifically dealing with ice-covered areas,Russia’s(along with other circumpolar states)latitude to enact and enforce measures to protect the fragile marine environment and ensure safe navigation is noticeably widened in the icy Arctic.①UNCLOS,Art.234 reads:Coastal States have the right to adopt and enforce non-discriminatory laws and regulations for the prevention,reduction and control of marine pollution from vessels in ice-covered areas within the limits of the exclusive economic zone,where particularly severe climatic conditions and the presence of ice covering such areas for most of the year create obstructions or exceptional hazards to navigation,and pollution of the marine environment could cause major harm to or irreversible disturbance of the ecological balance.Such laws and regulations shall have due regard to navigation and the protection and preservation of the marine environment based on the best available scientific evidence.This,plus a possible claim to special Arctic governance privileges under the enclosed and semi-enclosed seas regime created by UNCLOS,②Joshua Owens,Enclosed and Semi-Enclosed Seas:A Glimpse at State Practice with Special Regard to the Arctic,China Oceans Law Review[to be published](asserting that a similar regime based on the enclosed and semi-enclosed seas’regime may be established in the Arctic ocean).constitutes the primary leverage Russia possesses under international law for enforcing above-and-beyond measures in the Arctic.③There are,of course,other international treaties that influence Russia’s governance of its Arctic waters,but none so germane to the issues at hand as the ones discussed above.A list of other relevant sources of international law with implications for Arctic governance may be found in Michael A.Becker,Russia and the Arctic:Opportunities for Engagement within the Existing Legal Framework Symposium:Russia and the Rule of Law:New Opportunities in Domestic and International Affairs,American University International Law Review,Vol.25,2010,pp.233~234.

The Bering Strait,due to the influx of warmer Pacific currents,does not stay ice-covered for as much of the year as more northerly portions of the Arc-tic,①See Lynn Mc Nutt,How Does Ice Cover in the Bering Sea Vary from Year to Year?,National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association(NOAA),Bering Climate Essay,undated and unpaginated,at http://www.beringclimate.noaa.gov/essays_mcnutt.html,2 November 2011(observing that ice usually begins forming in the Northern Bering Sea in late fall and lasts until late spring).but the two littoral States’enforcement of article 234 measures for the protection of the Arctic environment will probably remain enforceable at the Bering Strait since traffic that crosses the Strait has either just exited or will promptly enter more northerly Arctic waters.Such measures,however,must be enacted and implemented with“due regard to navigation.”②UNCLOS,Art.234.Obviously this discourages a coastal State’s hindrance of or interference with navigation, therefore any attempts on Russia’s part to curtail or prevent free navigation through the Bering Strait would likely be met with protests from other nations,including America,whose position will be discussed in the following section.At any rate,since the Strait is two-sided,in the event Russia’s policy proved unacceptable to navigators,they could easily opt to cross the Strait in America’s territorial sea;if fees for crossing the Strait through America’s territorial sea are levied,this increase in traffic would only result in an advantageous situation for America,one an Arctic competitor would be loth to grant.③The collection of fees by a riparian state from vessels merely transiting through its territorial sea is not allowed,while charging for special services is.See UNCLOS,Art.26.

The USSR used straight baselines in order to set the boundaries of its maritime zones,to which the US protested.④Pacific Ocean,Sea of Japan,Sea of Okhotsk,and Bering Sea:Straight Baselines:USSR, Limits in the Seas,No.107,US State Dept.,Office of the Geographer,1987,at http:// www.law.fsu.edu/library/collection/limitsinseas/ls107.pdf,p.3,2 December 2011.This source states that many of USSR’s straight baselines“do not meet the international legal criteria for drawing such baselines.”See also Sam Bateman and Clive Schofield,Conference Paper,State Practice Regarding Straight Baselines in East Asia:Legal,Technical and Political Issues in a Changing Environment,presented at Difficulties in Implementing the Provisions of UNCLOS,Monaco,2008,unpaginated(remarking that“[t]he former USSR claimed a system of straight baselines in the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Japan,which has been protested by the United States”),at http://www.gmat.unsw.edu.au/ablos/ABLOS08Folder/Session7-Paper1-Bateman.pdf,2 December 2011.Its straight baselines enclose certain straits between the Russian coast and four Russian archipelagos:the Vilkitski,Shokalski,Dmitri Laptev and Sannikov.⑤Katarzyna Zysk,The Evolving Arctic Security Environment,in Stephen Blank ed.,Russia in the Arctic,2011,Strategic Studies Institute,at http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute. army.mil/pubs/download.cfm?q=1073,p.108,2 December 2011.The Russian Federation ispresumed to have inherited the former USSR’s maritime claims unless otherwise declared,①Maritime Claims Reference Manual,US Dept.of Defense,2005[hereinafter MCRM],at http://www.jag.navy.mil/organization/documents/mcrm/MCRM.pdf,p.489,2 December 2011.but where the Bering Strait is concerned,the straight baselines leave an ample amount of territorial sea;②Map:USSR Straight Baseline Claims in the Bering Sea,accompanying Limits in the Seas, No.107,1987,US State Dept.,Office of the Geographer,at http://www.law.fsu.edu/library/collection/limitsinseas/maps/ls107b.html,2 December 2011.for this reason,there is no need to assess in great depth the validity of Russia’s straight baselines under the framework provided by UNCLOS in order to ascertain its probable stance toward navigation through the Bering Strait,though it may be worthwhile to take note of Russia’s declaration upon ratifying UNCLOSin 1997:to wit,that while the Federation chooses to exclude from compulsory dispute resolution as provided for in UNCLOS those issues“relating to sea boundary delimitations,or those involving historic bays or titles,”it also clearly“objects to any declarations and statements made in the past or which may be made in future[sic] when signing,ratifying or acceding to the Convention,or made for any other reason in connection with the Convention,that are not in keeping with the provisions of article 310 of the Convention.The Russian Federation believes that such declarations and statements,however phrased or named,cannot exclude or modify the legal effect of the provisions of the Convention in their application to the party to the Convention that made such declarations or statements,and for this reason they shall not be taken into account by the Russian Federation in its relations with that party to the Convention.”③This declaration may be viewed by clicking“Russian Federation”,at http://www.un. org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_declarations.htm,2 December 2011.From this it may be surmised that Russia does not consider its use of straight baselines to be out of conformity with the provisions of UNCLOS.④See UNCLOS,Arts.298(1)(a)(i),309,310.The US disagrees:according to the MCRM,US Dept.of Defense,2005,at http://www.jag.navy.mil/organization/documents/mcrm/MCRM.pdf,p.489,2 December 2011,Russia’s straight baseline claims“are not recognized by the U.S.U.S.protested claims in 1984-1987 and conducted operational assertions in 1982,1984,and 1986.”Whether its deliberate exclusion of claims to“historic bays or titles”from the UNCLOS dispute resolution mechanism reveals a level of uncertainty about the legal legitimacy of its straight baseline claims is a matter of conjecture.

According to the US Department of Defense,the“1998[Federal Act onInternal Maritime Waters,Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone of the Russian Federation]does not appear to have revoked Russia’s historic bay claims.”①MCRM,2005,US Dept.of Defense,at http://www.jag.navy.mil/organization/documents/mcrm/MCRM.pdf,2 December 2011.Conversely it does not appear to have increased the extent of its internal waters to include the Bering Strait,nor has any other piece of legislation to the author’s knowledge.

2.Domestic Legislation

Close analysis of Russia’s regulations concerning navigation in its Arctic waters has already been conducted by abler scholars,②See Erik Franckx,The Legal Regime of Navigation in the Russian Arctic,Journal of Transnational Law&Policy,Vol.18,2009,p.327;Leonid Tymchenko,The Northern Sea Route:Russian Management and Jurisdiction over Navigation in Arctic Seas,in Alex G.Oude Elferink and Donald Rothwell ed.,The Law of the Sea and Polar Maritime Delimitation and Jurisdiction,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff Publishers,2001;R.Douglas Brubaker,The Russian Arctic Straits,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff Publishers,2005.so the present essay will refrain from repeating it in detail.Suffice to say that Russia’s domestic legislation-though it grants greater enforcement rights and concedes to fewer obligations than might be ascribed to it under international law,particularly regarding straight baselines-is outdated and due for revision.③Erik Franckx,The Legal Regime of Navigation in the Russian Arctic,Journal of Transnational Law&Policy,Vol.18,2009,p.342(noting that“substantial changes are to be expected concerning the legal regime applicable to foreign shipping in the Russian Arctic in a not too distant future”).As pointed out earlier,foreign vessels are now,albeit in small numbers,being allowed to cross the NSR without icebreaker assistance.④Michael A.Becker,Russia and the Arctic:Opportunities for Engagement within the Existing Legal Framework Symposium:Russia and the Rule of Law:New Opportunities in Domestic and International Affairs,American University International Law Review,Vol. 25,2010,p.241.This suggests an increasing willingness to open up the NSR to foreign traffic.On another note,Russia’s own legislation makes clear that most of the Bering Strait does not constitute part of the NSR,⑤The relevant legislation provides that the NSR ends“in the east(in the Bering Strait)by the parallel 66 N and the meridian 168 58′37″W.”1990 Regulations for Navigation on the Seaways of the Northern Sea Route,approved 14 Sept.,1990,29 Izveshcheniia Moreplavateliam[Notices to Mariners](18 June,1991)(Rus.),quoted in Erik Franckx,The Legal Regime of Navigation in the Russian Arctic,Journal of Transnational Law&Policy, Vol.18,2009,p.331.This point lies some ten minutes’latitude north of the Diomede Islands,a distance of about 18 km(10 nm).See map 2.thus making any attempt to prohibit or hinder navigation through the Strait under the pretense of its being part of the NSR legally untenable.Inconclusion,the preceding analysis suggests that Russia is under the international obligation to grant innocent passage through its territorial sea;recognition of the Bering Strait’s status as a strait used for international navigation would oblige it to allow navigators the right of transit passage through the Strait;even so,Russia would be entitled to certain rights pertaining to protection of the environment in ice-covered areas,as recognized in other parts of this contribution;①See sec.IV of the present text and UNCLOS,Art.234.and lastly,it would be desirable for Russia to harmonize its regulatory efforts with those of America in enacting and implementing such measures in the Bering Strait.

B.America

The United States of America boasts a strong tradition of upholding maritime freedoms and traditional uses of the oceans such as navigation and overflight,②See Reagan’s Statement on U.S.Oceans Policy,10 March,1983,International Legal Material s,Vol.22,1983,p.464;American Journal of International Law,Vol.77,1983,p. 619.For a detailed account of US protests against“excessive maritime claims”,including restrictions on navigation,see Robert Smith,Navigation Issues in the Law of the Sea,in Kim,Park,Lee&Paik ed.,Maritime Issues in the 1990s:Antarctica,Law of the Sea and Marine Environment,Seoul Press,1991,pp.87~125;See also J.Ashley Roach&Robert W.Smith,United States Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims,2nded.,The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff,1996.and the same approach is to be expected regarding the Bering Strait. As has been aptly pointed out before,the US position on transit passage is“well known.”③J.Ashley Roach&Robert W.Smith,United States Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims,2nded.,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff,1996,p.284.Roach and Smith cite telling sources,including US-dispatched aide-memoires and other such diplomatic documents,that illustrate clearly America’s desire to maintain freedom of transit passage in SUFINs.④J.Ashley Roach&Robert W.Smith,United States Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims,2nded.,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff,1996,pp.284~287.For instance,President Reagan stated in no equivocal terms that“[i]n accordance with international law,as reflected in the applicable provisions of[UNCLOS], within the territorial sea of the United States,the ships of all countries enjoy the right of innocent passage and the ships and aircraft of all countries enjoythe right of transit passage through international straits.”①Presidential Proclamation 5928,27 December 1988.Cited in J.Ashley Roach&Robert W.Smith,United States Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims,2nded.,The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff,1996,p.285.Regarding warships,the US asserts that their mere exercise of transit passage poses no threat to the territorial sovereignty of a coastal State.②Aide-memoire delivered 4 December 1984 from American Embassy Stockholm,State Department telegram 355149,1 December 1984;American Embassy Stockholm telegram 08539,10 December 1984.Cited in J.Ashley Roach&Robert W.Smith,United States Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims,2nded.,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff,1996,p. 286.The US takes the position that“transit passage also applies in the approaches to international straits.”③J.Ashley Roach&Robert W.Smith,United States Responses to Excessive Maritime Claims,2nded.,The Hague:Martinus Nijhoff,1996,pp.286~287.According to a recent US State Department fact sheet,“[p]ast Administrations (Republican and Democratic),the U.S.military,and relevant industry and other groups have all strongly supported joining the Convention.”④Fact Sheet on the Law of the Sea Convention,1 July 2011,Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs,[emphasis in original],at http://www.state. gov/g/oes/lawofthesea/factsheets/177207.htm,2 December 2011.There has been no indication of the US government’s changing its position concerning transit passage through international straits since the days of Reagan;regarding the Bering Strait,the question that remains,then,is whether it qualifies as a strait used for international navigation.As concluded above in sectionⅡ(c,d) and in other sources,the answer is indubitably yes.⑤See Arctic Council 2009,Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report,Arctic Council, Norwegian Chairmanship,Oslo,Norway,at http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/ en/about/documents/category/62-pame?download=245:the-amsa-2009-report,p. 109,30 November 2011;Donald Rothwell,Arctic Choke Points and the Law of the Sea, Australian National University—ANU College of Law Research Paper No.10~81,2010, p.17(relaying the US military’s view:“Bering Strait East[the US half]and Bering Strait West[the Russian half]are recognized by the US Navy as international straits for the purposes of the LOSC.”).In light of these circumstances,from a policy perspective it can be safely assumed that the US would make every effort to ensure the right of all nations’vessels to transit passage through its territorial sea within the Bering Strait.

From a commercial standpoint,increased traffic often results in increased revenue(on the assumption that a portion of transiting vessels will call at A-merican ports or utilize other special services),which presumably aligns with America’s development-oriented interests.As noted earlier,the US may wish to closely regulate Arctic traffic insofar as it promotes the preservation of thefragile Arctic marine ecosystem.①See Jerry Beilinson,Oil Drilling in the Arctic Ocean:Is It Safe?,24 June 2011,Popular Mechanics,at http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/energy/coal-oil-gas/oildrilling-in-the-arctic-ocean-is-it-safe,4 November 2011(observing that the conclusion regarding the safety of offshore drilling in the Arctic in a recent USGS study“seems to be that there’s still a great amount we just don’t know”).Ideally such measures will not be implemented unilaterally but rather through appropriate international fora such as the Arctic Council or the International Maritime Organization(IMO):these organizations have already issued relevant documents,like the 2009 Arctic Marine Ship ping Assessment and the recently revised Guidelines for Ships Operating in Polar Waters,respectively.In any case,environmental-protection measures need not unduly hinder freedom of navigation.In conclusion,it is highly improbable that the US will attempt to impede the reasonable exercise of transit passage through the Bering Strait.②See Wang ZeLin,Research on the Legal Status of Arctic Passage,Doctoral Thesis,Xiamen University,2011(Ch.),p.33(recounting the US interpretation that straits may be considered SUFINs regardless of the point in time at which international navigation commences);William Schachte,International Straits and Navigational Freedoms,Remarks prepared for presentation to the 26th Law of the Sea Institute Annual Conference Genoa, Italy,1992(relating the US’s view that navigational freedoms are paramount and should be preserved to the fullest extent possible),at http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/65946.pdf,30 November 2011.See also Christopher Mark Macneill,Gaining Command and Control of the Northwest Passage:Strait Talk on Sovereignty,Transportation Law Journal,Vol.34,2007,pp.356~364(reiterating US’s stance toward the freedom of navigation through the Northwest Passage).

Ⅳ.Some Suggestions for Future Bering Strait Administration

With the aim of effectively managing the Bering Strait by encouraging free navigation and commerce while simultaneously protecting the delicate Arctic marine environment,the two littoral states have many options at their disposal,and indeed may begin to proactively implement some or all of them immediately,before the Strait becomes more frequently transited by commercial vessels.Naturally certain administrative privileges must be granted to America and Russia at the Bering Strait since only their territorial seas and no high seas lie within.This may include the right to levy payment for expenditures such asspecial services like navigational aids or pilotage fees;①This would be fully in accordance with UNCLOS,Art.26,which stipulates:(1)No charge may be levied upon foreign ships by reason only of their passage through the territorial sea;and(2)Charges may be levied upon a foreign ship passing through the territorial sea as payment only for specific services rendered to the ship.These charges shall be levied without discrimination.also foreign States must comply with local regulations enacted in accordance with international law,including domestic environmental,customs or immigration laws.②See UNCLOS,Art.42(4).That being said,it would nevertheless be prudent,necessary even,for the riparian states to coordinate and cooperate with the relevant international organizations -especially the Arctic Council and IMO-to draft and implement legislation regarding through-Strait navigation.The IMO’s Guidelines for Ships Operating in Ice-Covered Waters will no doubt serve as a useful tool in Bering Strait administration,although they are legally non-binding.③ϕystein Jensen,The IMO Guidelines for Ships Operating in Arctic Ice-covered Waters: From Voluntary to Mandatory Tool for Navigation Safety and Environmental Protection?, 2007,Fridtjof Nansen Institute,(stating the desirability of establishing binding legal requirements for ships operating in polar waters),at http://www.fni.no/doc&pdf/FNIR0207.pdf,pp.23~24,4 November 2011.These guidelines were revised in 2009,but without the effect of achieving legally binding status.④Developing a Mandatory Polar Code-Progress and Gaps,Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition,34thAntarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting in Buenos Aires 2011,at http:// asoc.org/storage/documents/Meetings/ATCM/XXXIV/Developing_a_Mandatory_Polar_ Code___Progress_and_Gaps.pdf,p.3,30 November 2011.Negotiations are currently underway for promulgating a binding polar code through the IMO,possibly as soon as 2013.⑤Developing a Mandatory Polar Code-Progress and Gaps,Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition,34thAntarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting in Buenos Aires 2011,at http:// asoc.org/storage/documents/Meetings/ATCM/XXXIV/Developing_a_Mandatory_Polar_ Code___Progress_and_Gaps.pdf,p.6,30 November 2011.

Direct cooperation between the two littoral States would also be most desirable.Through the open sharing of scientific knowledge and professional surveys and assessments,the two would be better equipped to cooperatively designate ideal shipping lanes,⑥UNCLOS,Art.41.identify and mitigate environmental concerns,and cost-effectively install sufficient navigational aids and communications equipment;⑦UNCLOS,Art.43.with political harmony and solidarity,the two could together devise an administrative framework that protects the interests of both sides as well as prevents foreign States from resorting to potential loopholes like the one men-tioned above.①See sec.Ⅲ(A)of the present text.The two parties have reached a preliminary agreement regarding oil spill preparedness and response in the Bering and Chukchi Seas,②The Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics concerning Cooperation in Combating Pollution in the Bering and Chukchi Seas in Emergency Situations(signed 11 May 1989,entered into force 17 August 1989),U.N.T.S.,No.2190,p.180.yet judging from the specificity of the agreement’s scope of application,other important environmental aspects are not covered therein.The AMSA 2009 points out several concerns regarding the establishment of safe and sustainable navigational conditions in the Bering Strait that remain outstanding.③Arctic Council 2009,Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report,Arctic Council, Norwegian Chairmanship,Oslo,Norway,at http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/ en/about/documents/category/62-pame?download=245:the-amsa-2009-report,p. 109,30 November 2011:current areas in need of improvement include emergency response such as search and rescue;lack of differential GPS coverage,sufficient navigational aids, very-high frequency communication services and a traffic separation scheme.If fees,regulations and requirements are standardized,there would be no preference among foreign ships to cross through one country’s territorial sea instead of the other’s;though inequality in traffic volume would not necessarily result in tensions,it is nonetheless a possibility if monetary concerns are taken into account:for instance,should one State shoulder more of the financial burden if a higher number of vessels crosses the Strait through its territorial sea?On that note,international discussion should be conducted to reach consensus on how the appropriate environmental,navigational or other relevant fees are to be levied for the proper management of the Bering Strait.

The littoral States could take the examples of long-established SUFINsamong which the most notable example is perhaps the Straits of Malacca and Singapore-as they devise a system tailored to the administration of the Bering Strait.④For pre-UNCLOS commentaries on Malacca Straits administration,see Michael Leifer, Malacca,Singapore and Indonesia,Sijthoff and Noordhoff,1978;See also Nadaisan Logaraj,Navigational Safety,Oil Pollution and Passage in the Straits of Malacca,Malaya Law Review,Vol.20,1978,p.287.For more current treatments,see Lim Lei Theng,Safety of Navigation in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore:Modalities of Cooperation, Rapporteur’s Report,Singapore Journal of International&Comparative Law,Vol.2, 1998,p.254;NihanÜnlü,Straits of Malacca,International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law,Vol.21,No.4,2006,p.539.Previous approaches to issues such as pollution prevention,vessel standards,law enforcement and shipping lane designation could serve as references and,where necessary,be modified to fit the polar environment.One cru-cial issue in establishing proper Bering Strait management is that of procuring adequate funding.In the Straits of Malacca,a major source of funding for the provision and maintenance of navigational aids like buoys and beacons has been the Malacca Strait Council of Japan.①Gurpreet S.Singhota,The IMO’s Role in Promoting Safety of Navigation and Control of Marine Pollution in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore,Singapore Journal of International&Comparative Law,Vol.2,1998,p.291.This demonstrates that interested parties other than the littoral States will likely be willing to help cover necessary costs associated with achieving an environment conducive to safe navigation in the Bering Strait:thus Russia and America should consider identifying those parties likely to consider safe navigation in the Arctic as vital to their interests. Some candidates include Asian shipping behemoths like China,Japan,Hong Kong,Taiwan and Korea;other frequent users might be Norway,Canada,Iceland and the United Kingdom.Of course,private sources-particularly the shipping industry-should also be taken into consideration.

Within the last few years,the States bordering the Straits of Malacca (namely Indonesia,Malaysia and Singapore)have been cooperating with the IMO and other user States to enhance safety and security in the Straits,approaching management issues comprehensively.②See Joshua H.Ho,Enhancing Safety,Security,and Environmental Protection of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore:The Cooperative Mechanism,Ocean Development&International Law,Vol.40,2009,p.233.One noteworthy outgrowth of this cooperative scheme is the Marine Electronic Highway(MEH),a“navigation support and management system that integrates marine environmental management and protection systems(EMPS)and state-of-the-art marine navigation technologies.”③Joshua H.Ho,Enhancing Safety,Security,and Environmental Protection of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore:The Cooperative Mechanism,Ocean Development&International Law,Vol.40,2009,p.236.Joshua Ho explains:“The MEH will provide vital marine information,such as tides and currents,to ships on a real-time basis and allow integrated electronic navigation.The EMPS will be able to map out the trajectory of oil and chemical spills,provide spill damage assessments,monitor coastal and ocean environments,and provide environment impact assessments. The MEH enables accurate navigation for every ship under the overall traffic management system,which will significantly improve the security of shipping and safety of navigation and,consequently,reduce the risk of accidents that

g

gmay result in catastrophic environmental pollution.”①Joshua H.Ho,Enhancing Safety,Security,and Environmental Protection of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore:The Cooperative Mechanism,Ocean Development&International Law,Vol.40,2009,p.236.Installation of this system has yet to be completed.Not only does this large-scale endeavor show the feasibility of obtaining funding from interested parties,but also highlights the desirability of littoral and user States enlisting the support of IMO in implementing such projects.

This user/riparian States consortium created a“Cooperative Mechanism”in 2006 meeting in Kuala Lumpur built around proposals for six major projects,including“cooperation and capacity building on hazardous and noxious substances(HNS)preparedness and response in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore,including the setting up of HNS Response Centres,”②Joshua H.Ho,Enhancing Safety,Security,and Environmental Protection of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore:The Cooperative Mechanism,Ocean Development&International Law,Vol.40,2009,p.237.and the“setting up of a tide,current,and wind measurement system for the Straits of Malacca and Singapore to enhance navigational safety and marine environment protection.”③Joshua H.Ho,Enhancing Safety,Security,and Environmental Protection of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore:The Cooperative Mechanism,Ocean Development&International Law,Vol.40,2009,p.238.The US and Russia should consider implementing similar projects in the Bering Strait with the help of other interested parties and the IMO, especially in light of the high volume of oil,gas and other noxious substances which can be expected to transit the Bering Strait in the future.Since it is relatively shallow,frequent and accurate hydrographic surveys made publicly available would also contribute to safe navigation through the Strait.The US Coast Guard’s high frequency of vessel inspections and imposition of“draconian”penalties have contributed to a reduction in the proportion of substandard vessels operating in US waters.④Ho-Sam Bang,Is Port-State Control an Effective Means to Combat Vessel-Source Pollution?An Empirical Survey of the Practical Exercise by Port States of Their Powers of Control,International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law,Vol.23,2008,p.744.In order to prevent sub-standard vessels detouring through less regulated Russian waters(if that were indeed the case),it would behoove the two nations to reach consensus through a memorandum of understanding(MOU)or some such instrument to achieve uniformity in vessel inspections and raise overall shipping quality through the Strait.

Lastly,for convenience Russia and America might also consider institutinga road-like orientation within the Bering Strait:the Strait is already bisected naturally by the Diomede islands,which point could serve as a median,on either side of which the direction of traffic would be opposing.In theory,if northbound vessels transited the American side and southbound vessels went through Russia’s territorial sea,the two nations would see a roughly equal volume of traffic;at the same time,risk of collision would be reduced because all the ships would generally travel in an orderly fashion.Navigation between the two Diomedes at the narrow divide containing the international boundary could be prohibited barring special circumstances.

Ⅴ.Conclusion

The rise of Arctic navigation is just now at its incipience.With further melting of Arctic ice,one expects that the advantage of shorter shipping routes will draw no few navigators north to traverse the Arctic passages.En route, these vessels are likely to cross through the Bering Strait.Because of the geopolitical stature that the Strait may attain,the question of its legal status should be resolved without delay,thus contributing to lasting stability and prosperity for commercial navigation in the Arctic.The Strait should be considered a strait used for international navigation where the right of transit passage may be exercised.The littoral States should respect this right,but at the same time endeavor to appropriately manage the Strait with the aim of preserving the integrity of the Arctic marine environment.Russia and America should strive to cooperate with each other as well as with user states and the relevant international organizations to streamline systems such as shipping lanes,vessel standards,law enforcement,fee schedules,communications equipment and navigational aids,etc.By learning from previous examples of SUFIN management,Russia,America and the rest of the world will be assured of establishing a sound and sustainable framework of administration in the Bering Strait.Figures and Maps

Figure 1UNEP/GRID-Arendal.Arctic sea routes—Northern sea route and Northwest passage. UNEP/GRID-Arendal Maps and Graphics Library(2007).Available at:http://maps.grida. no/go/graphic/arctic-sea-routes-northern-sea-route-and-northwest-passage.Accessed 13 Oct 2011.

Map 1NOAA,Office of Coast Survey.Map of US Maritime Zones/Boundaries.Available at http://www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/csdl/mbound.htm(last updated 26 May 2011).Accessed 11 Oct 2011.Image captured via Google Earth.This map depicts the Russian-American international boundary as defined in the 1990 USSoviet Boundary Agreement.

Map 2NOAA,Office of Coast Survey.Map of US Maritime Zones/Boundaries.Available at http://www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/csdl/mbound.htm(last updated 26 May 2011).Accessed 11 Oct 2011.Image captured via Google Earth.This map is a close-up image of the boundary contained in map 1(above).It shows the boundary splitting the Diomedes;note the existence of only territorial sea between Little Diomede Island(US)and Cape Prince of Wales.

Map 3Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report,p.107.Vessel traffic in the Bering Strait during the summer of 2004.

(Editor:HAN Xu)

*Joshua Owens,National Quemoy University in Taiwan’s Marine Affairs Institute.E-mail: jko113@gmail.com.

杂志排行

中华海洋法学评论的其它文章

- 北极航道法律地位研究

- Study on the Legal Status of the Arctic Navigation Routes

- The Accountability of the Offshore Drilling Platform’s Oil Pollution Damages in the COPC Incident:In Comparison with the United States Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Incident

- China Oceans Law Review Call For Papers

- CHINA OCEANS LAW REVIEWCUMULATIVE TABLE OF CONTENTS(ISSUES 1-13)

- 康菲钻井平台油污损害的赔偿责任问题

——以美国钻井平台漏油事件的处理为比较