Small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis with hepatocellular carcinoma requiring liver transplantation

2010-12-14SharifAliandVeenaShah

Sharif Ali and Veena Shah

Detroit, USA

Small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis with hepatocellular carcinoma requiring liver transplantation

Sharif Ali and Veena Shah

Detroit, USA

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010; 9: 208-212)

primary sclerosing cholangitis;small-duct diseases of the liver;hepatocellular carcinoma;liver transplantation

Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a chronic in fl ammatory disease of the bile ducts, typically affects anywhere from the small interlobular to large intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts, and leads to progressive bile duct fi brosis and liver cirrhosis. In 1969, Bhathal et al[1]reported a case of an elderly male patient who presented with chronic cholestasis and had a liver biopsy showing extensive concentric periductal fi brosis involving the small interlobular bile ducts. A follow-up intraoperative cholangiogram demonstrated irregularities and incomplete fi lling of the intrahepatic part of the biliary tract but a normal extrahepatic biliary tree. He called this phenomenon a primary intrahepatic obliterating cholangitis, a possible variant of PSC. In 1985, Wee and Ludwig[2,3]replaced the old terminology of pericholangitis, which was originally used to describe the histological changes found in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis without large-duct involvement, to small-duct PSC and suggested that pericholangitis,small-duct PSC, and both intra- and extrahepatic largeduct types make up the spectrum of PSC syndrome.

Case report

A 31-year-old African American male factory worker presented to the emergency room in November 2000 with severe hematemesis due to grade Ⅳ variceal bleeding and required endoscopic banding, blood, and platelet transfusions, and subsequent hospital admission.On examination, the patient was fully oriented,appeared well-developed, and was well-nourished with no muscle wasting. The sclera was anicteric. His blood pressure was 112/68 mmHg, pulse 89 beats/min. Skin examination showed no stigma of chronic liver disease.On abdominal examimation, he had mild hepatomegaly and a normal sized spleen.

His review of symptoms was unremarkable and hedenied any family history of gastrointestinal or liver disease. His social history was signi fi cant for occasional marijuana smoking and alcohol intake since the age of 26, which he stopped completely soon after he presented.The patient had a single lifelong sexual partner and denied intravenous drug use.

Pertinent laboratory studies on admission showed WBC 2.9×109/L (normal 3.8-10.6×109/L), hemoglobin 13.1 (normal 13.5-17.0) g/dl, platelets 62×109/L (normal 150-450×109/L), AST 78 (normal, 15-35) IU/L, ALT 101(normal, 30-65) IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 343 (normal 0-120) IU/L, total bilirubin 1.9 (normal <1.2) mg/dl,and normal serum albumin.

HAV, HBV, and HCV screening antibody serology and autoimmune work-up including antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA),and anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA) were all negative. Serum ceruloplasmin, alpha 1 antitrypsin, and ferritin were normal.

He underwent an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) as a work-up of his cholestatic biochemical liver function which showed a small 5 mm cholesterol stone which was extracted from the common hepatic bile duct with subsequent normal fi lling of the intrahepatic biliary tree.

The patient was provisionally diagnosed with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis and was started on supportive therapy with a close follow-up.

Over a course of eight years, from 2001 until 2008, the patient experienced multiple episodes of hematemesis, pancytopenia due to splenic sequestrations,and decreased level of serum albumin reaching a nadir of 1.5 (normal, 3.7-4.8) g/dl.

In November 2008, the patient presented with acute left upper quadrant pain. Chest X-ray revealed right pleural effusion, which was adequately managed and showed negative for malignant cells on cytology. Later on, the patient had abdominal ultrasound showing acute portal vein thrombosis. He was evaluated by the multidisciplinary liver transplantation team and a recommendation of liver transplantation was made.

Pre-transplantation work-up revealed an elevated alpha fetoprotein (AFP) of 200 (normal <8.1) ng/ml.Subsequently abdominal ultrasound failed to visualize liver masses. Contrast enhancing CT scan with triple phase was contraindicated because of impaired kidney function. Serum creatinine was fl uctuating around 2.9 (normal 0.9-1.3) mg/dl. A liver donor was soon available and the patient underwent an ABO-compatible orthotopic liver transplantation from a deceased donor with duct-to-duct anastomosis and infrarenal graft.

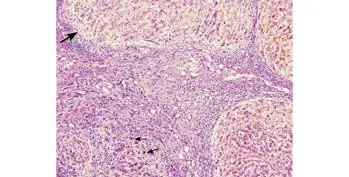

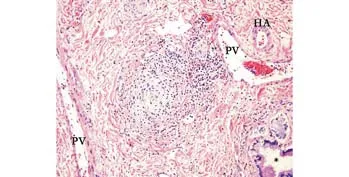

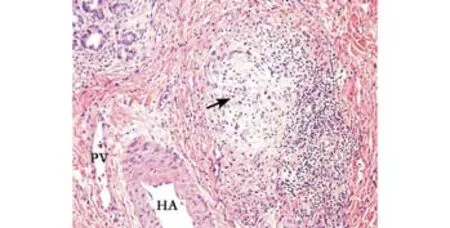

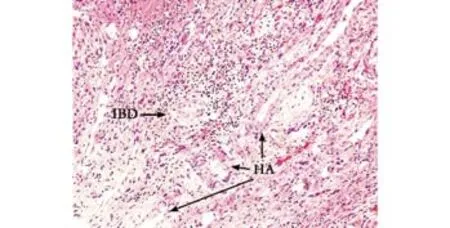

Histopathological examination of the explanted liver showed an extensively bile-stained nodular liver and three incidental nodules of moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma in the right lobe measuring 0.6 to 4.6 cm. Multiple sections of the non-neoplastic liver showed markedly distorted architecture. The small and medium-sized portal tracts were widened by dense collagen bands with much portocaval and portoportal fi brosis. The portal tract contained a moderate amount of in fl ammatory in fi ltrate consisting of lymphocytes,neutrophils, plasma cells, and scattered eosinophils. No granulomas or lymphoid follicles were identi fi ed. The in fi ltrate was much denser around the bile ducts. The limiting plates disclosed dense lymphocytic interface activity and extensive ductular proliferation. The periportal parenchymal hepatocytes showed swollen rari fi ed cytoplasm containing bile pigment. The bile canaliculi were prominent and often contained bile thrombi (Fig. 1). The small and medium-sized bile ducts were all histologically abnormal due to concentricperiductal fi brosis, and many of the small interlobular bile ducts were replaced by fi brous scars accompanied by the branches of hepatic arteries and portal veins (Figs.2-4). The large bile ducts were generally intact. The combined periductal fi brosis of the small and mediumsized ducts and the decreased numbers of interlobular bile ducts with ductular proliferation supported a diagnosis of small-duct PSC.[2,3]

Fig. 2. Medium-sized bile duct with concentric periductal fi brosis surrounded by cuffs of mixed inflammatory cells. There is the unremarkable nearby septal bile duct (*). HA, hepatic artery branch; PV: portal vein branch (Hematoxylin and eosin, original magni fi cation ×100).

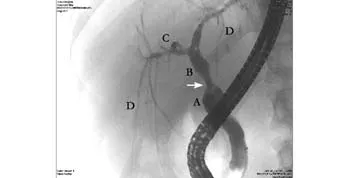

Fig. 5. Six months post-transplantation follow-up cholangiogram. The surgical anastomotic stricture is seen in the mid common bile duct (arrow) with pre- and post-stenotic dilatation.A: native common bile duct; B: common extrahepatic donor bile duct; C: right main hepatic duct; D: segmental and septal bile ducts. The complete filling of the intrahepatic biliary tree indicates no evidence of large duct disease.

The patient's post-operative course was complicated by abdominal pain, which prompted exploration. The patient developed mild biliary tract stricture at the site of anastomosis which subsequently was evaluated by ERCP and stent placement. Repeated cholangiograms did not show any evidence of recurrence or progression of disease into large-duct type. His post-operative AFP level dropped to <3.0 ng/ml 3 months after surgery. He remained free of any signs of recurrence or metastatic disease. His renal function improved after transplantation,with serum creatinine returning to normal (range 0.8-1.4 mg/dl, last checked on 12/21/2009).

Discussion

Small-duct PSC is a disease that affects middle-aged males. In a study[4]the median age of patients with this disease was 39 years (range 16-75) and 63% of them were male. About 30% of patients with this disease are symptomatic at the time of diagnosis, but most patients may present with jaundice, right upper quadrant pain,pruritus, fever, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, or variceal bleeding.[5-11]Apart from fatigue, abdominal pain seems to dominate in the early stage and pruritus is often seen evidently during follow-up. Asymptomatic patients usually show an incidence chronic cholestatic liver pro fi le on routine examination.

Fifty to seventy percent of patients with smallduct PSC have a history of in fl ammatory bowel disease(IBD). About 78% of the patients have ulcerative colitis,21% have Crohn's colitis, and one patient reported had collagenous colitis. Sometimes IBD symptoms appear years after the liver disease or after liver transplantation.[5,7]Our patient did not show symptoms suggesting IBD, and post-transplant colonoscopy with random colon biopsies showed no in fl ammation. In cases of contrast to primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), there is no current biochemical marker to support the diagnosis of small-duct PSC. In large-duct PSC, 60%-90% are tested positive for atypical perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA). P-ANCA has been reported in a patient with small-duct PSC.[12]

Histological examination of liver specimens remains a cornerstone for the diagnosis of small-duct PSC,which is characterized by fi brous or fi bro-obliterative"onion skin" periductal concentric fi brosis around the small interlobular and medium-sized septal bile ducts along with a decreased number of interlobular bile ducts(ductopenia) and ductular proliferation. According to Wee and Ludwig,[2,3]this pattern is rarely seen in any condition other than small-duct PSC.

Small-duct PSC must be differentiated from other cholestatic liver diseases that may involve the small intrahepatic bile ducts, including primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune cholangitis, idiopathic adulthood ductopenic syndrome, drug-induced bile duct damage,and large-duct variant for prognostic facts.

Primary biliary cirrhosis is a progressive nonsuppurative in fl ammation, and destruction of interlobular bile ducts occurs predominantly in middle-aged women(female/male 9/1). AMA as a marker is seen in 95%of cases although it is not necessary for diagnosis.Granulomatous cholangitis and fl orid bile duct damage are characteristic microscopic fi ndings. Autoimmune cholangeitis shares similar clinical and histological features with primary biliary cirrhosis, except autoimmune antibodies other than AMA are often detected.The majority of cases may present ANA and ASMA in patients' serum.[12,13]Adulthood ductopenic syndrome as a new entity was described fi rst by Ludwig in 1988.[14]All cases reported occurred in adults, with a slight male predominance (male/female, 2/1), from the early teens up to age 67 years (median, 27). Diagnosis of the syndrome depends on liver biopsy showing progressive ductopenia (vanishing bile duct syndrome) with or without periportal in fl ammatory in fi ltrate, and clinical and laboratory fi ndings are incompatible with those of other small-duct biliary diseases. Most may have a poor prognosis with liver cirrhosis and hepatic failure. To the present, no recurrent disease has been reported in the liver graft.[15,16]

Drug-induced cholestatic liver disease is associated with destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts mimicking other small-bile duct disorders clinically, biochemically,and histologically. There is a protracted course of acute cholestasis shortly, often 4-6 weeks, after administration of a drug or exposure to toxins and followed by prompt symptomatic relief after cessation. While cases of slowly progressive disease with superimposed vanishing bile duct syndrome and secondary biliary cirrhosis have been reported.[13,16]

Large-duct PSC disease is usually diagnosed by cholangiography or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which is considered as sensitive as ERCP in diagnosing PSC.[10,17]Cholangiography shows the multifocal strictures, irregularities (beading) of intraand/or extrahepatic bile ducts. Cholangiography should disclose the intrahepatic biliary tree. Liver biopsies are performed usually after the diagnosis to stage fi brosis.In small-duct type disease, the diagnosis is dependent on the liver biopsy as cholangiography is negative.Furthermore, ERCP or MRCP is repeated as some patients may progress to have large-duct PSC with extraand intrahepatic biliary bile duct involvement. In a study,[6]4 of 32 patients with small-duct PSC progressed to have large-duct PSC in a median follow-up of 72 months (range 12-192). In two patients only intrahepatic bile duct changes were noted. The other two had both intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts involved.[6]In our patient, multiple consecutive cholangiograms were taken at 1, 3, 4, 6 and 9 months post-transplantation,showing an anastomotic stricture in the mid common bile duct (Fig. 5), but normal fi lling of the intrahepatic bile ducts.

The close association of the disease with IBD has led to trials of treatment with aminosalicylates (ASA). In a study[4]2 of 6 patients showed rapid normalization of laboratory tests after administration of ASA, even though they had no evidence of IBD in serial intestinal biopsies.Meanwhile, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is widely used for various cholestatic liver diseases. Attempts have been made to treat small-duct PSC with UDCA, but very limited data are available. A study of 23 patients treated had UDCA for at least 2 years showed two patients had elevated bilirubin level at baseline normalized after 6 and 24 months of treatment.[6]Liver transplantation remains the ultimate cure of small-duct PSC. Our patient did not receive any treatment for his primary liver disease after transplantation and was maintained successfully on cyclosporine 25 mg QAM, methyl prednisolone 2 mg daily,and mycophenolate 250 mg twice/day. Like large-duct PSC, just as in autoimmune or viral hepatitis, small-duct PSC is reported to recur in the liver graft. In a study,[5]2 of 83 patients required retransplantation 9 and 13 years later for recurrent small-duct PSC with cirrhosis. The two patients medicates that small-duct PSC is recurrent after liver transplant. Our patient underwent three transcutaneous ultrasound guided liver biopsies within a month after transplantation, which were suggestive of bile duct obstruction but there was no apparent evidence of disease recurrence or acute cellular rejection.

In conclusion, small-duct PSC seems to run a course more benign than the large-duct type and has less chance of developing end-stage liver disease. Cholangiocarcinoma,the most fearful complication, occurs in 10%-20%of patients with large-duct PSC. To our knowledge,cholangiocarcinoma has not yet been reported in smallduct only PSC unless it progresses to the large-duct type. Contrarily, hepatocellular carcinoma is reported in both types of PSC patients; the incidence seems to be incidental and unrelated to the disease process.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Contributors: AS wrote the fi rst draft of this commentary. Both authors contributed to the intellectual context and approved the fi nal version. AS is the guarantor.

Competing interest: No bene fi ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Bhathal PS, Powell LW. Primary intrahepatic obliterating cholangitis: a possible variant of 'sclerosing cholangitis'. Gut 1969;10:886-893.

2 Wee A, Ludwig J. Pericholangitis in chronic ulcerative colitis:primary sclerosing cholangitis of the small bile ducts? Ann Intern Med 1985;102:581-587.

3 Ludwig J. Small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis 1991;11:11-17.

4 Nikolaidis NL, Giouleme OI, Tziomalos KA, Patsiaoura K, Kazantzidou E, Voutsas AD, et al. Small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. A single-center seven-year experience.Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:324-326.

5 Björnsson E, Olsson R, Bergquist A, Lindgren S, Braden B,Chapman RW, et al. The natural history of small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 2008;134:975-980.

6 Broomé U, Glaumann H, Lindstöm E, Lööf L, Almer S, Prytz H,et al. Natural history and outcome in 32 Swedish patients with small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). J Hepatol 2002;36:586-589.

7 Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Angulo P, Enders FB, Lindor KD.Impact of in fl ammatory bowel disease and ursodeoxycholic acid therapy on small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis.Hepatology 2008;47:133-142.

8 Björnsson E, Boberg KM, Cullen S, Fleming K, Clausen OP,Fausa O, et al. Patients with small duct primary sclerosing cholangitis have a favourable long term prognosis. Gut 2002;51:731-735.

9 Rasmussen HH, Fallingborg JF, Mortensen PB, Vyberg M,Tage-Jensen U, Rasmussen SN. Hepatobiliary dysfunction and primary sclerosing cholangitis in patients with Crohn's disease.Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:604-610.

10 Chapman RW, Arborgh BA, Rhodes JM, Summer fi eld JA, Dick R, Scheuer PJ, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review of its clinical features, cholangiography, and hepatic histology.Gut 1980;21:870-877.

11 Angulo P, Maor-Kendler Y, Lindor KD.Small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis: a long-term follow-up study. Hepatology 2002;35:1494-1500.

12 Tervaert JW, van Hoek B, Koek G. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis.Gastroenterology 2009;136:364-365.

13 Geubel AP, Sempoux C, Rahier J. Bile duct disorders. Clin Liver Dis 2003;7:295-309.

14 Ludwig J, Wiesner RH, LaRusso NF. Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia. A cause of chronic cholestatic liver disease and biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1988;7:193-199.

15 Poupon R, Chazouillères O, Poupon RE. Chronic cholestatic diseases. J Hepatol 2000;32:129-140.

16 Desmet VJ. Vanishing bile duct syndrome in drug-induced liver disease. J Hepatol 1997;26:31-35.

17 Ernst O, Asselah T, Sergent G, Calvo M, Talbodec N, Paris JC,et al. MR cholangiography in primary sclerosing cholangitis.AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;171:1027-1030.

BACKGROUND: Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic progressive cholestatic liver disease, which usually affects young adults and is diagnosed by cholangiography. On a few occasions, the disease either starts in or exclusively involves the small intrahepatic bile ducts, referred to as small-duct PSC.

METHODS: A 31-year-old man presented with severe hematemesis secondary to liver cirrhosis. Over a course of 8 years, his liver decompensated and required an orthotopic liver transplantation.In this report we discuss his disease presentation, course of management, and the post-transplantation course of management, and review the morphologic diagnosis, and differential diagnosis of the disease with large-duct type and other diseases that involve small intrahepatic bile ducts.

RESULTS: The patient's explanted liver showed changes of PSC affecting only the small- and medium-sized bile ducts in addition to three incidental nodules of hepatocellular carcinoma.

CONCLUSIONS: Small-duct PSC has a substantially better prognosis than the large-duct type, with less chance of developing cirrhosis and an equal risk for developing hepatocellular carcinoma, but no increased risk for developing cholangiocarcinoma. Treatment seems to help relieve the symptoms but not necessarily improve survival. Liver transplantation remains the ultimate cure.

Author Af fi liations: Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine,Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI 48202, USA (Ali S and Shah V)

Sharif Ali, MD, Division of Anatomical Pathology,Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Henry Ford Health System, 2799 West Grand Blvd. K-6, Detroit, MI 48208, USA (Tel: +11-313-916-8330; Fax: +11-313-916- 2385; Email: sali2@hfhs.org)

© 2010, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

December 8, 2009

Accepted after revision February 13 , 2010

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Delayed hepatocarcinogenesis through antiangiogenic intervention in the nuclear factor-kappa B activation pathway in rats

- Effect of blueberry on hepatic and immunological functions in mice

- Impact of human leukocyte antigen matching on hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation

- Prognostic models for acute liver failure

- Proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins involving in liver metastasis of human colorectal carcinoma

- Protective effects of MCP-1 inhibitor on a rat model of severe acute pancreatitis