Sport Concussion—The Field Evaluation

2010-11-17StevenBroglioPhDATC

Steven P.Broglio,PhD,ATC

Neurotrauma Research Laboratory

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Introduction

Concussion related to sporting activities occur between 1.6 and 3.8 million times a year in the United States[14].The occurrence varies between sporting events[1],but medical personnel are likely to face this injury at least once in theircareer.The highly variable nature ofconcussion makes the clinical evaluation difficult.For example,it is known that the location and severity of impact to the head[11],the number of previous concussions[10],gender[7],and age[6]will all influence both injury risk and duration of impairment following injury.To furthercomplicated the evaluation process,traditional imaging techniques,such as computed tomography(CT)or magnetic resonance imaging(MRI),do not posses the sensitivity necessary for diagnostic purposes.Thus,the clinician must rely on a thorough clinical examination[8]that is supported by objective measures for to make a concussion diagnosis.

The following document can serve as a guide for the sideline clinician assessing athletes suspected of sustaining a concussion.In a process similar to evaluating orthopedic injuries,the systematic approach outlined here will allow the clinician to identify and rule out other more serious injuries.Once an athlete is identified as having aconcussion,both thesportsmedicine clinician and a physician should be involved in the return to play be decision making process.

The On-Field Assessment

The most difficult portion of the concussion evaluation is identifying athletes with the injury.A majority of athletes continue to neglect to inform medical personnel about their injury[18]and virtually none will show any visible signs of injury.For example,only 10%of concussive injuries involve a loss of consciousness[5,10].In the event an athlete doesloseconsciousness,the clinician should suspect a cervical spine injury and follow the standard of care for that injury.In particular,when completing the primary survey(ie airway,breathing,and circulation)the cervical spine should be held in a neutral position.If the athlete regains consciousness and more severe injuries are ruled out,the athlete can be taken to the sideline for furtherevaluation.Ifthe athlete remains unconscious,he should be placed on a spine board and transported for advanced evaluation.

The broad spectrum of clinical outcomes resulting from concussion precludes the use of pre-injury data in the concussion evaluation process[2,20]That is each athlete should be evaluated when healthy to establish a baseline level of functioning so information obtained from an injured athlete can be directly compared to his pre-injury performance.A myriad of tests exist for this purpose,but the battery should include measures of symptomology,postural control,and neurocognitive function[9](discussed in detail below).

The earliest aspect of the sideline assessment should be to establish a mechanism of injury.In many cases the clinician will have witnessed the injury occur,but if this is not the case,the athlete or other members of the athletic team may provide beneficial information.If the athlete is engaged in questions,a level of consciousness can be established.If the athlete is not alert enough to understand the questions or passes in and out of consciousness,he should be transported for further evaluation.Questioning the athlete also allows the clinician to determine the presence of amnesia.Retrograde amnesia is the inability to recall events before the injury which can established by asking questions such as‘do you remember getting hit?’,‘do you recallthe play you were running?’,‘what team are we playing against?’,and‘do you remember arriving at the field before the game?’Alternatively,anterograde amnesia(the inability to recall events after the injury)can be assessed by asking questions such as‘who was the first person you saw on the field?’and‘do you recall coming over to the bench?’

The next series of questions should evaluate the presence/absence of concussion related symptoms.Countlesssymptomsare associated with concussion,butthe Graded Symptom Checklist(GSC:

Table 1)is widely used and endorsed by the National Athletic Trainers’Association [9].Each item can be ranked on a Likert scale of 0 to 6(0=notpresent,1=mild,3=moderate,and 6=mostsevere)The presentation of symptoms varies widely between concussed individuals,but concussed athletes tend to report headache(83%),dizziness(65%)and confusion(57%)most frequently [5,10,13,21].Importantly,older definitions of concussion requiring the athlete be rendered unconscious are not accurate as recent findings have found only 10%of all concussions result in this clinical sign [15].Athletes reporting any sign or symptom however,should be withheld from further play.

Table 1 Graded Symptom Checklist(GSC)

In many cases the observation and palpation portion of the evaluation can be completed while the clinician gathers history information.The cervical spine and facial bones should be palpated to rule out fractures.At the same time the clinician can interpret the athlete’s response to collect information on the presence/absence of aphasia[22].The clinician should also check pupil size equivalency,reaction to light,and nystagmus.Checking pulse and pulse pressure(ie systolic minus diastolic>60 mmHg)can rule out a life threatening condition.A pulse pressure that remains high after 10 minutes of rest[5],combined with a low pulse rate can indicate a brain hemorrhage[23].If any of these abnormalities are present upon examination the athlete should be transported to a medical facility.

Neurostatus,postural control,and cranial nerve integrity should be employed as the special tests for the evaluation process.Numerous tests have been used in the past,but tests such as Serial Sevens and questions such as“what is your name?”are not sensitive to the effects of concussion [16,19].Alternatively,the Standardized Assessment of Concussion(SAC)is a neurostatus exam requiring 5 or 6 minutes to administer and interpret[19].The SAC consists of 5 sections that evaluate the areas of Orientation,Immediate Memory,Concentration,and Delayed Recall.Post-injury performance should be compared to the baseline evaluation with decreases of 1 point or more suggesting impairment[3].

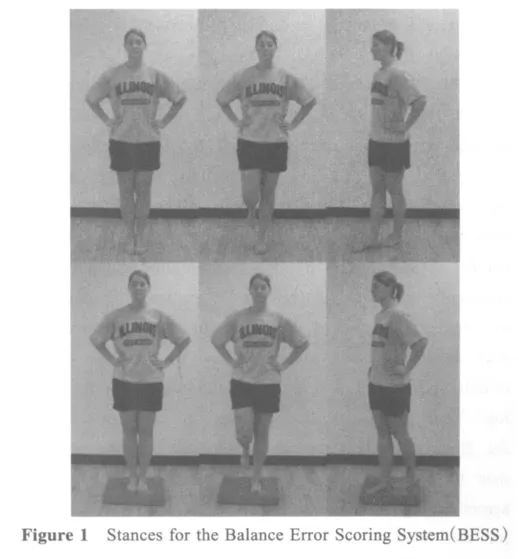

A commonly employed sideline postural control measure is the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS).The BESS test is conducted under 3 different stance conditions(Figure 1)completed on both firm and foam surfaces(eg Alcan Airex AG,Switzerland).Stances last 20 seconds with the hands on the hips with the eyes closed.Errors(

Table 2)are counted with greater errors representing worse balance. Increas es of 3 or more errors at post-injury compared to the baseline test is thought to represent a significant change[24].

Table 2 Balance Error Scoring System(BESS)counTable errors[12]

When the clinician notesa significantchange in number of reported symptoms,SAC(1 or more point decrement[3]),or BESS score(3 or more point increase[24])the athlete should be removed from play.Should the athlete have normal SAC and BESS scores and symptoms dissipate within 20 minutes,the athlete should continue to be withheld as symptoms may continue to develop following injury[10].

Rupture to the cranial nerves is rare the sporting environment,but injury to the nervs can coincide with concussion.A detailed description of this assessment protocol is beyond the scope of this paper,but other resources can be found outlining this material[17].Should a deficit to a cranial nerve be noted in the post-injury evaluation the athlete should be transported to a medical facility for further evaluation.

Testing of the neck musculature is only warranted if symptom reports,BESS,and SAC scores are within normal scores.Both active and passive range of motion(ROM)for flexion,extension and rotation should be conducted;followed by manual muscle testing in the same directions.Limitations to ROM or muscle strength warrant an athlete being withheld as the restrictions may place the athlete at risk for further injury by reducing the visual field(ie neck rotation and scanning)or injury protection(ie neck bracing).

The final portion of the evaluation is functional testing.A functional assessment should only be used when the athlete appears normal on all aspects of the evaluation and isnota same day return to play protocol.Functional testing is the last step in ensuring the athlete does not have symptoms that may present under the demands of sport participation.The sideline functional assessment should be progressive in nature with the onset of symptoms queried at each step.In many instances tests such as the Valsava maneuver,push-ups and sit-ups are initially performed with jogging and short sprints following.Sport specific drills completed at game intensity are the final step.If symptoms emerge following any step then the athlete should not be returned.If there are no symptoms and all other tests are normal(eg SAC and BESS)then the athlete has likely not sustained a concussion and can be returned to play.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that concussion continues to be one ofthe mostcomplex and misunderstood injuries faced by sports medicine personnel.With virtually no visible signs and symptoms the clinician must rely on a clinical exam supported by objective tests to make the injury diagnosis.To avoid missing the often subtle changes associated with the injury,the clinical examination should follow a systematic process of history,observation,special tests,range of motion,manual muscle and functional tests.Continuousthroughoutthe processthe clinician should ask about the development or return of symptoms.In no instance should the athlete continue playing on the same day if he reports a symptom related to concussion.The final return to play decision should adopt a team approach which includes the athlete,parents,coaches,and physician.

[1]National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Summary for 15 sports:1988-1999 through 2003-2004.J Athl Train 42[2].2007.

[2]Aubry M,Cantu R,Dvorak J et al.Summary and agreement statement of the first International Conference on Concussion in Sport,Vienna 2001.Br J Sports Med 2002 February 1;36(1):6-10.

[3]Barr WB,McCrea M.Sensitivity and specificity of standardized neurocognitive testing immediately following sports concussion.J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2001;7(6):693-702.

[4]Dart AM,Kingwell BA.Pulse pressure-a review of mechanisms and clinical relevance.J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37(4):975-84.

[5]Delaney JS,Lacroix VJ,Leclerc S,Johnston KM.Concusions among university football and soccer players.Clin J Sport Med 2002;12(6):331-8.

[6]Field M,Collins MW,Lovell MR,Maroon JC.Does age play a role in recovery from sports-related concussion?A comparison of high school and collegiate athletes.J Pediatr 2003;142(5):546-53.

[7]Gessel LM,Fields SK,Collins CL,Dick RW,Comstock RD.Concussions among United States high school and collegiate athletes.J Athl Train 2007;42(4):495-503.

[8]Grindel SH,Lovell MR,Collins MW.The assessment of sport-related concussion:The evidence behind neuropsychological testing and management.Clin J Sport Med 2001;11(3):134-43.

[9]Guskiewicz KM,Bruce SL,Cantu RC et al.National Athletic Trainers’Association Position Statement:Management of Sport-Related Concussion.J Athl Train 2004;29(3):280-97.

[10]Guskiewicz KM,McCrea M,Marshall SWet al.Cumulative effects associated with recurrent concussion in collegiate football players:The NCAA concussion study.JAMA 2003;290(19):2549-55.

[11]Guskiewicz KM,Mihalik JP,Shankar V et al.Measurement of head impacts in collegiate football players:relationship between head impact biomechanics and acute clinical outcome after concussion.Neurosurgery 2007;61(6):1244-52.

[12]Guskiewicz KM,Ross SE,Marshall SW.Postural stability and neuropsychological deficits after concussion in collegiate athletes.J Athl Train 2001;36(3):263-73.

[13]Guskiewicz KM,Weaver NL,Padua DA,Garrett WE.Epidemiology ofconcussion in collegiate and high school football players.Am J Sports Med 2000 September;28(5):643-50.

[14]Langlois JA,Rutland-Brown W,Wald MM.The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury:A brief overview.J Head Trauma Rehabil 2006;21(5):375-8.

[15]Lovell MR,Iverson GL,Collins MW,McKeag DB,Maroon JC.Does loss of consciousness predict neuropsychological decrements after concussion?Clin J Sport Med 1999;9(4):193-8.

[16]Maddocks DL,Dicker GD,Saling MM.The assessment of orientation following concussion in athletes.Clin J Sport Med 1995;5(1):32-5.

[17]Martin JH.Neuroanatomy:Text and Atlas.2 ed.Stamford:Appleton & Lange;1996.

[18]McCrea M,Hammeke T,Olsen G,Leo P,Guskiewicz K.Unreported concussion in high school football players:implications for prevention.Clin J Sport Med 2004 January;14(1):13-7.

[19]McCrea M,Kelly JP,Kluge J,Ackley B,Randolph C.Standardized assessment of concussion in football players.Neurology 1997 March;48(3):586-8.

[20]McCrory P,Johnston K,Meeuwisse Wet al.Summary and agreement statement of the second International Conference on Concussion in Sport,Prague 2004.Br J Sports Med 2005 April;39(4):196-204.

[21]McCrory PR,Ariens M,Berkovic SF.The nature and duration of acute concussive symptoms in Australian football.Clin J Sport Med 2000;10:235-8.

[22]Ropper AH,Gorson KC.Clinical practice:Concussion.N E-ngl J Med 2007;356(2):166-72.

[23]Sanders MJ,McKenna K.Head and Facial Trauma.Mosby's Paramedic Textbook.2nd ed.Mosby;2001.p.624-51.

[24]Valovich McLeod TC,Barr WB,McCrea M,Guskiewicz KM.Psychometric and measurement properties of concussion assessment tools in youth sports.J Athl Train 2006;41(4):399-408.