Diplomacy Still Matters

2010-10-14KERRYBROWN

Diplomacy Still Matters

Fu Ying accomplished a great deal during her time as China’s ambassador to the UK

The departure from London of Madam Fu Ying, China’s Ambassador to the UK for the past three years, to take up a new post in Beijing was a reminder of the often lowprofile but key work that diplomats still do.

Fu was the fi rst female ambassador from China to the UK, and the fi rst of Mongolian ethnicity. She came after serving with distinction in Australia, and in the Asian region where she had worked on dif fi cult issues in Cambodia, Indonesia and the Philippines.She also had the great advantage of being familiar with the UK, having studied at the University of Kent in the mid-1980s. As she said in her leaving address in London, her love of English literature gave her not just a social bond with the UK, but also an emotional one.

Because of the explosion of global communications systems, it might seem strange in the second decade of the 21st century there are more diplomats than ever based abroad. In the very earliest period of diplomatic history, envoys were sent, sometimes for many years at a stretch, to remote parts of the world, with only very occasional contact with their home country. They were there to gather information and to help communicate with countries that may have never had contact with each other before. They worked in great isolation. It took months for messages to and fro to be delivered.

In the 19th century, as Britain’s interests increased dramatically around the world,diplomats were sent to Asia, Africa, the Americas and the Middle East. They were often powerful political fi gures in their own right, having enormous influence in the places where they were sent. They were a fundamental part of international relations.In the middle part of the 20th century, diplomats worked hard to avoid war, and, when global war happened, worked to deal with its aftermath. Throughout the Cold War,they were often one of the few links between countries. One of the great achievements of President Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972 was to start having more U.S. diplomats based in Beijing.

When I started work as a diplomat in the 1990s for the British Foreign Office, I remember in one of our introductory talks being told by the head of the foreign service that even with the arrival of e-mail,fax and other communications tools, it was very unlikely “any time soon” that there would be a reduction in the need for a diplomatic service. The devastating results of the September 11 attacks in 2001 in New York only highlighted this. Before long diplomats in the United Nations, in the Middle East,and in the rest of the world, were wrestling with a new era, in which global terrorism posed a major threat.

In the early 1990s, U.S. theorists such as Francis Fukayama were talking about the disappearance of major global conflict and the start of a new period in which a kind of political stability reigned over the planet.Con fl icts such as the Cold War were a thing of the past. The struggle against terrorism showed newer threats had appeared, and they were linked to religion and ideology, rather than nation states. That made them far harder to track and engage.

The face of China

Fu is an outstanding representative of one of the world’s most extensive and admired foreign services. Her work in the UK is a good example of why, even with 24-hour news coverage and endless sources of information and analysis, diplomacy still matters.

The UK and China have a long historic association. The UK was one of the earliest countries to recognize the People’s Republic of China (PRC) when it was founded in 1949. A British liaison office headed by a charge d’affaires was based in Beijing throughout the 1950s and 1960s. It was upgraded to ambassadorial level in 1972 after the visit of Prime Minister Edward Heath to China that year. China’s Embassy in the UK actually dates back to the late Qing Dynasty(1644-1911). Sun Yat-sen, a pioneer of China’s democratic revolution, even took refuge there in the early part of the 20th century while brie fl y based in London. The building is one of the longest continuously occupied embassies in London.

For more than a decade, the key interest between the UK and China was the handling of the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty from 1980 onwards. These discussions allowed the UK and China to start learning about each other in great depth.There were numerous ups and downs. Most of the detailed work on the fi nal agreement for the handover was achieved by diplomats on both sides.

Perhaps a testimony to their work can be seen in the largely successful development of Hong Kong since 1997, when it became a special administrative region of the People’s Republic. The Basic Law, agreed by both sides before 1997, which serves as ade-factoconstitution for Hong Kong, has survived most of the challenges posed in the last 13 years. That is a tribute to the huge work put into fi nalizing agreement on this document by China’s and Britain’s diplomats over almost 10 years.

Since 1997, the focus of the interests between the UK and China has shifted more to economic cooperation. With China’s continuing reform and opening up, greater numbers of Chinese companies have come to invest in the UK. Large companies like COSCO, Huawei and the Bank of China, have of fi ces in the UK. Central China Television and Alibaba have their European headquarters in London. London has become, since 1997, a major center for finance, despite the global economic downturn since 2007.

In Fu’s period as ambassador,a further 15 companies from China came to list on the London Stock Exchange, joining the 40 that had already fl oated. More than 150 new companies came to invest in the UK,making the country the most popular destination for Chinese investment, overtaking Germany in 2008.Chinese tourists increased from just more than 100,000 in 2007 to 175,000 in 2009. Perhaps the most remarkable statistic is that there are

85,000 Chinese students studying at universities in the UK—almost the same number as those in the United States.

There were two major events that occurred while Fu was ambassador, which illustrate the strengths and challenges of the UK-China relationship. One was the Beijing Olympics in 2008 attracting global attention to China, and the other was the international effort building up to the G20 conference in London in April 2009 to deal with the global fi nancial crisis.

For both events, Fu was critical as the face of China in the UK, appearing in TV and press interviews and explaining China’s position on political and economic issues. For the Olympics, she was able to engage with the criticisms and anxieties about China’s emerging economic power and pro fi le, setting them alongside the remaining huge challenges China faced within its own borders to continue to reform and develop. For the fi nancial crisis, she was able to explain both in public and directly to key British politicians what the response of the Chinese Government was going to be and how it wanted to work with international partners.

Providing a foundation

The need to have a figure in a country who is able to communicate directly to its people about the intentions of China was one of the most striking features of Fu’s time in the UK. She herself made clear she was concerned about the messages that were being conveyed about China and the misunderstanding that existed amongst some groups.

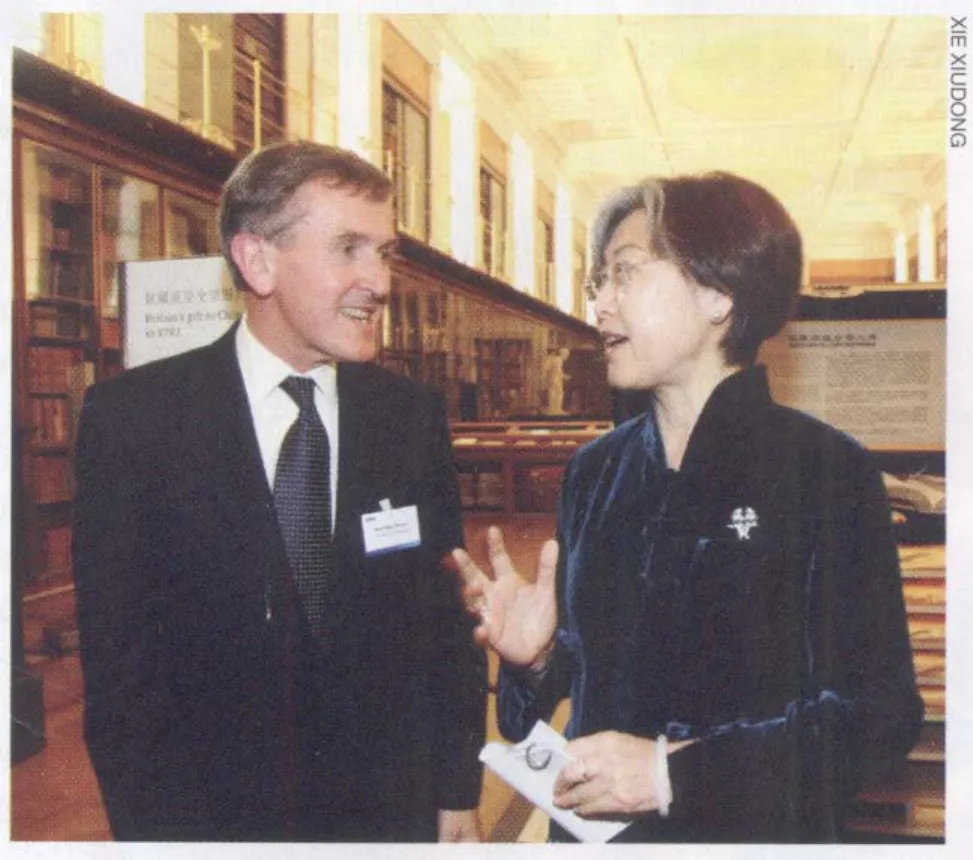

CHINA’S ENVOY: Fu Ying, Chinese Ambassador to the UK, holds a reception opening the exhibition of the Compiled British Illustrations—a series of books sent by British King George III to Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty as a gift in 1793—in the British Museum in London on May 30, 2007

Talk of a “China threat” and of China somehow having a master plan to extend its influence globally in places such as Africa,Asia and the Middle East in ways that would conflict with developed countries increased when statistics showed each year from 2006 major rises of Chinese investment in these areas. A point she made on many occasions in public in the UK was China had committed itself since early in the reform process to working with the outside world, and that it had bene fi ted from a stable, benign international environment.

Her presentation of the concept of“peaceful” rise was at least able to set out, in the mainstream media in the UK, why China was committed to this path and why it was actively engaged in international diplomacy to work with other partners, not against them.

It may well have been a result of her patient and polite diplomacy that led to the UK in late 2008 changing its position on Tibet,from being the only country to merely recognize Chinese suzerainty, or special in fl uence,in the autonomous region, to recognizing fully the PRC’s sovereignty there. This led the way to the fi rst British ministerial visit to Tibet in October 2009.

She uniquely saw the visit by both Chinese President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao to the UK, and Prime Minister Gordon Brown to China, over six months from the beginning of 2009. In 2009 alone she hosted more than 400 delegations from China to Britain and saw more than 35 ministerial visits from Britain to China in return.

What a diplomat can only ever do is to provide a foundation. With these links between the UK and China, and with large areas of common interest,there is nothing to gain from con fl ict and contention between both sides.But there are certainly areas where in the coming months and years there will be hard talk.

The UK and China did not see eye to eye during the climate change conference at Copenhagen in December 2009. Through the European Union,there are ongoing trade issues around market access, protectionism and the value of the Chinese renminbi, or yuan. There will need to be tough talk between both sides on how to deal with issues over the global cyber environment, drawing up some common and accepted rules on how cyberspace should be policed and regulated so that everyone’s interests are protected.

The whole point of diplomatic effort, however, is to make sure that

there is plenty of understanding and communication beforehand, so that when problems happen—problems always will happen, even in the most harmonious of relations—then both sides are well placed to work through these, and make sure that things don’t get out of hand.

Fu was exemplary in dealing even with tough issues where the governments of the UK and China disagreed politely, fi rmly and clearly. She put forward China’s case in a way where, even if people disagreed, they could at least understand it, and try to fi nd a way of drawing the two sides closer.

Her successor has a great foundation to move forward on, and with increasing numbers of schoolchildren in the UK studying Chinese, visiting China and having Chinese come to stay with them in the UK, however hard the dialogue becomes in the future, we are in a good place to deal with it and make sure we end up both coming out feeling we’ve achieved the best result.

(The viewpoints in this article do not necessarily represent those ofBeijing Review)

The author is a senior fellow at the Royal Institute of International Affairs in Britain