Maritime Issues between China and Japan and the Prospect for Resolution

2010-04-07ZOUKeyuan

ZOU Keyuan

Maritime Issues between China and Japan and the Prospect for Resolution

ZOU Keyuan*

China and Japan are close neighbors in East Asia and their maritime encounters and communications can be traced back several thousands of years.In recent years,the two countries have developed their maritime relations in various ways,including,inter alia,marine fishery management,joint marine scientific research,and joint efforts in the protection of the marine environment.Although there is much cooperation between the two sides in the maritime sector,tensions and even conflicts do exist in their maritime relations.

China;Japan;Maritime issues;Prospect for resolution

Ⅰ.Introduction

China and Japan are separated by the East China Sea,which is defined in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea(LOS Convention) as a semi-enclosed sea.①According to Article 122 of the LOS Convention,“enclosed or semi-enclosed sea”means a gulf,basin or sea surrounded by two or more States and connected to another sea or the ocean by a narrow outlet or consisting entirely or primarily of the territorial seas and exclusive economic zones of two or more coastal States.Text is reprinted in 21 I.L.M.(1982) 1261.During the debate on the issue of enclosed and semi-enclosed seas at the second session of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1974,the East China Sea was referred to within the general classification of enclosed and semi-enclosed seas. See Michael W.Lodge,“The Fisheries Regimes of Enclosed and Semi-enclosed Seas and High Seas Enclaves”,in Ellen Hey(ed.),Developments in International Fisheries Law (The Hague:Kluwer Law International,1999),p.197.It covers about 480,000 sq mi(1,243,190 sq km)and is bounded by the islands of Cheju(north),Kyushu(northeast),Ryukyu (east)and Taiwan(south)and by Mainland China(west).②“East China Sea”,in The New Encyclopaedia Britannica,15th Edition,vol.3,Encyclopaedia Britannica,Inc.,1984,p.756.It is a marginal sea with a wide continental shelf,and its average depth is 370 metres with a maximum of 2,719 metres.In recent years,the East China Sea has shown unrest not only in its tidal waves and natural movements,but also in political and legal confrontations particularly between China and Japan.

The LOS Convention was adopted in 1982 and entered into force in 1994. Both China and Japan ratified the Convention in 1996.China has taken several legislative moves in response to the implementation of the LOS Convention.In 1992 China promulgated the Law on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone③The English version may be found in Office of Ocean Affairs,Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs,US Department of State,Limits in the Seas,No.117(Straight Baselines Claim:China),July 9,1996,pp.11-14.—which has improved the territorial sea regime established under the 1958 Declaration on the Territorial Sea-defining the limits of its territorial sea and contiguous zone at a breadth of 12 nm of 24 nm,respectively,measuring from the coastal baselines.This law applies to all of China,including Taiwan and the various islands located in adjacent seas under Chinese jurisdiction.

Another fundamental Chinese maritime statute is the Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf,adopted by the NationalPeople’s Congress in 1998.①The Chinese text is reprinted in People’s Daily(in Chinese),30 June 1998.An English translation may be found in Law of the Sea Bulletin,No.38,1998,pp.28-31.This law is designed to guarantee China’s exercise of sovereign rights and jurisdiction over its exclusive economic zone(EEZ)and continental shelf,and to safeguard its maritime rights and interests.According to this law,China’s EEZ consists of the area beyond and adjacent to China’s territorial sea,extending up to 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.As for China’s continental shelf,it comprises the sea-bed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond China’s territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin,or to a distance of 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured where the outer edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that distance.②Article 2 of the Law on EEZ and Continental Shelf.It is interesting to note that although the provision to define the EEZ is just a copy of the relevant provision of the LOS Convention,the provision regarding the continental shelf has something new with Chinese characteristics,that is,the emphasis on the natural prolongation of China’s rights to the continental shelf,which bears strong implications for the delimitation of the continental shelf in the East China Sea.③Zou Keyuan,China’s Marine Legal System and the Law of the Sea Leiden:Martinus Nijhoff,2005,p.94.The Law further provides that EEZs and continental shelves with overlapping claims between China and the countries with opposite or adjacent coasts should be determined by agreement in accordance with the equitable principle on the basis of international law.

In May 1996 when China was ratifying the LOS Convention,China issued a declaration on its baselines.China uses the method of straight baselines to define the limits of its territorial sea around part of the mainland and the Xisha (Paracel)Islands.④Declaration on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea of the People’s Republic of China,15 May 1996,at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/CHN_1996_Declaration.pdf,17 December 2009.Meanwhile,China stated that it would announce the remaining baselines of its territorial sea at another time.

In the Decision on the Ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,China made a statement that:

1.In accordance with the provisions of the United Nations Conven-tion on the Law of the Sea,the People’s Republic of China shall enjoy sovereign rights and jurisdiction over an exclusive economic zone of 200 nautical miles and the continental shelf.

2.The People’s Republic of China will effect,through consultations,the delimitation of the boundary of the maritime jurisdiction with the States with coasts opposite or adjacent to China respectively on the basis of international law and in accordance with the principle of equitability.

3.The People’s Republic of China reaffirms its sovereignty over all its archipelagos and islands as listed in article 2 of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the territorial sea and the contiguous zone, which was promulgated on 25 February 1992.①The declaration is available at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/ convention_declarations.htm#China%20after%20ratification,29 July 2009.

The above statement clearly shows the official position of China regarding the maritime boundary delimitation and reiterates its claims to the disputed islands in the East China Sea.

Japan took a similar domestic legislation process.In 1977 it adopted the Law on Territorial Sea and in 1996 the Law on EEZ and Continental Shelf. Unlike China,though,it also promulgated the Basic Ocean Law in 2007,which provides legal guidance for a unified and comprehensive ocean policy and administration.②A Chinese translated version is available at China Oceans Law Review,2008,No.1,pp. 128-133.Regarding maritime boundary delimitation with neighbouring countries,Japan has advocated the application of the median line as a delimitation line for the EEZ and the continental shelf in the absence of an agreed line with the opposite country.This is reflected in its 1996 EEZ Law.③See Article 1(2)and Article 2(2)of the Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf(Law No.74 of 1996),Law of the Sea Bulletin,No.33,1997,pp.94-95.Thus,the ratification of the LOS Convention and the adoption of relevant domestic laws and regulations offer a legal basis for present-day maritime interactions between China and Japan.

Ⅱ.Bilateral Fishery Relations

In order to avoid fishery conflicts and to maintain a normal fishing order inthe East China Sea,China and Japan began to discuss such matters as early as the 1950s.Since there were no official diplomatic ties between the two,the authorized parties for negotiation were non-governmental entities backed by both their governments.In June 1955,a first(non-governmental)fishery agreement was reached between the Japan-China Fisheries Council(originally known as Japan-China Fisheries Enterprise Association)and the China Fisheries Association.From 1955 to 1975,excluding five years from June 1958 to November 1963,three non-governmental fishery agreements(1955,1963 and 1965)were negotiated and implemented,and they played a very critical role in establishing and developing fishery relations between China and Japan.

The non-governmental agreement established fishing zones(6 zones for trawling and 3 for seine operations)by way of limiting the maximum number of fishing boats and fishing seasons.For some areas,the horsepower of fishing boats was also limited.Limitations on the length of fish and the mesh size of fishing nets were imposed.The agreement also established a joint commission, composed of three members from each country,which helped to implement the agreement.①The Japanese side proposed that the commission conduct a joint scientific survey,but China refused this on the ground of its three principles,i.e.,self-reliance,independence,and achievement of a planned economy.See Shoichi Tanaka,Japanese Fisheries and Fishery Resources in the Northwest Pacific,Ocean Development and International Law,vol.6, 1979,p.184.The total allowable catch(TAC)for trawlers under the agreement was limited to 200,000 tons,covering a variety of demersal species,such as croaker and hairtail,and the amount for purse seine catches was 300,000 tons centering on mackerel and jack mackerel.②Shoichi Tanaka,Japanese Fisheries and Fishery Resources in the Northwest Pacific,Ocean Development and International Law,vol.6,1979,p.184.Remarkably,the fishery agreement established conservation zones in the East China Sea in the 1950s,a time when the idea of sustainable development had not come into being.It is also notable that such conservations zones covered areas in the high seas.

Following the establishment of diplomatic ties,the two countries commenced consultations on a governmental fishery agreement.The Fishery A-greement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of Japan was finally signed on 15 August 1975,and came into force on 23 December 1975.③Text in Fishery Administrative Bureau,Ministry of Agriculture,PRC(ed.),Sino-Japanese Governmental Fishery Agreements and Non-Governmental Protocols on the Safety of Fishing Operations(in Chinese),April 1993,1-19.Meanwhile,the non-governmental agreement wasterminated.The 1975 Agreement was revised in 1978 and 1985.①They are concerned with the establishment of a horsepower restriction line inside which trawlers and purse seiners of 600 hp or more are prohibited to enter;closed areas or suspension areas which are completely closed during designated periods;and fishing restrictions concerning minimum body length,minimum mesh size,light intensity fish-attracting devices,incidental catch limit.See Mark J.Valencia,A Maritime Regime for Northeast Asia Hong Kong:Oxford University Press,1996,p.258.Although the 1975 agreement introduced more rigid protective measures than the previous non-governmental agreements,in other aspects it was largely the same.

The entry into force of the LOS Convention in 1994 ushered in a new era of fishery relations between China and Japan.Both countries established their EEZs based on the relevant provisions of the LOS Convention through their respective domestic legislations.Since the broadest width of the East China Sea is less than 400 nm,the whole sea area consists of EEZs that are shared by China,Japan and Korea.The fishery relationship between the two sides inevitably needed a new adjustment.After several rounds of negotiation,the two sides finally reached agreement in September 1997 regarding fishery management in the East China Sea.②Fishery Agreement between the People’s Republic of China and Japan,11 November 1997.An unofficial English translation is available in Zou Keyuan,Law of the Sea in East Asia:Issues and Prospects London:Routledge,2005,pp.175-180.The new agreement came into force on 1 June 2000.

The agreement contains some significant provisions in response to the changed situation:(a)affirming the principle of fishery resources conservation and protection:Pursuant to the relevant provisions in the LOS Convention and environmental requirements from Agenda 21 and others,the Agreement contains as one of its purposes the establishment of a new fishery order in accordance with the LOS Convention,conserving and utilising rationally marine living resources of common concern,and maintaining the normal operation order at sea.Both sides agree to cooperate to conduct scientific research regarding fishery and to conserve marine living resources.③Article 10 of the Sino-Japanese Fishery Agreement.Each should adopt necessary measures to ensure compliance by their nationals and fishing vessels with the provisions of the Fishery Agreement and the conservation measures and other conditions provided for in the relevant laws and regulations of the other Party when engaging in fishery activities in the other’s EEZ,and should inform each other of such conservation measures and other conditions provided for in its relevant laws and regulations.④Article 4 of the Sino-Japanese Fishery Agreement.(b)Providing reciprocal fishing rights:The A-greement applies to large portions of the two countries’EEZs,but specifically excludes the EEZ area south of 27°N,and west of 125°30′E in the East China Sea where Taiwan and the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands are located.Within the EEZ,China and Japan grant each other’s nationals and fishing vessels the right to fish in each other’s EEZs pursuant to the principle of reciprocity,the Fishery Agreement and their relevant domestic laws and regulations.The competent authorities of each Party issue fishing permits to nationals and fishing vessels of the other Party,and may levy appropriate fees upon issuance of such permits.The issuance of fishing permits to fishermen of the other nation should follow the relevant provisions of the Agreement.How many permits should be issued and how many tons of fish may be caught in the opposite party’s EEZ is a complicated and difficult matter that requires bilateral discussion and agreement.(c)Establishing the Provisional Measures Zone(PMZ): The Agreement creates the PMZ,which is located in the middle of the East China Sea,52 nm from the baselines of mainland China’s territorial seas and an equal distance from the coast of the Ryukyu Islands;its northern limit lies at a latitude of 30°40′N and its southern limit at 27°N.For conservation and quantity of fishery resources in the PMZ,both sides should adopt,based on decisions made by the Sino-Japanese Fishery Joint Committee,appropriate management measures in order to protect marine living resources from overexploitation.Each party should take administrative and other necessary measures for their nationals and fishing vessels fishing in the PMZ,and should not impose administrative and other measures on nationals and fishing vessels of the other party in this area.The establishment of a common fishery zone is a typical form of fishery cooperation for shared waters between any two countries;there are many such arrangements in the world,the Sino-Japanese PMZ is but one example.The PMZ is the first such zone between China and Japan,though there was some degree of fishery cooperation between the two sides before its establishment.It indicates that the fishery cooperation between these two countries has entered into a new era.(d)Maintaining the Joint Fishery Committee:In order to implement the fishery agreement as well as to coordinate respective fishery management procedures,both sides decided to establish the Joint Fishery Committee which consists of four members,two appointed by each Party.The decision-making mechanism is based on the unanimous consent of the committee members.Both sides have to respect recommendations made by the Joint Fishery Committee,and adopt necessary measures in accordance with its decisions.The Committee may be convened annually either inChina or in Japan and temporary meetings,if necessary,may also be held.①Article 11 of the Sino-Japanese Fishery Agreement.

Ⅲ.Cooperation in Handling Maritime Issues in the EEZ

The EEZ is a new maritime zone created by the LOS Convention and issues inevitably arise regarding activities in that zone.China and Japan had a dispute over Chinese scientific research vessels conducting marine scientific research(MSR)in the East China Sea.Japan accused China of violating Japan’s sovereignty and maritime interests.China argued that the boundary between the two countries had not yet been delimitated in that sea.As we know,freedom of marine scientific research is guaranteed under the legal regime of the high seas.Before the LOS Convention and the establishment of EEZs by China and Japan,scientific research could be conducted in the East China Sea beyond the territorial seas of the two countries freely.But after the LOS Convention, the legal status of certain sea areas previously considered high seas had changed:maritime scientific research in another country’s EEZ is subject to the consent of the coastal State as provided for in the LOS Convention.No EEZ boundary has been fixed between China and Japan,and there remain some areas in the East China Sea with overlapping claims.

In order to defuse the tension resulting from scientific research in overlapping areas in the EEZ,the two sides held talks on 15 September 2000 aiming to establish a framework for mutual prior notification of any marine survey activities in the waters around the two countries.As a result,an agreement was reached in 2001 on prior notification of any MSR activities in the disputed waters including the following main points:(a)notification is to take place two months in advance of any scheduled MSR investigation to be undertaken in the sea area adjacent to the jurisdictional waters of the other side;and(b)notification is to include the name of the institution and of the vessel involved in the MSR investigation,the purpose and contents of the investigation,and the period and the area of the investigation.②See Hong Kong Economic Journal(in Chinese),9 February 2001,p.10.The arrangement is a provisional measure pending the maritime boundary settlement between the two states,but it should ease any unnecessary tension resulting from MSR activities.

Another incident in the EEZ involving maritime interaction between the two countries occurred on 22 December 2001:an unidentified vessel was pur-sued by Japan’s Coast Guard in the East China Sea for encroaching on Japan’s EEZ sank after being fired upon by four Japanese coast guard patrol vessels.①According to some other reports,Japan sent altogether 25 patrol vessels and 14 aircraft to chase the mysterious boat.See Lu Lude,Japan cannot do as it pleases in China’s EEZ, China Ocean News(in Chinese),8 March 2002.All 15 crewmembers on board lost their lives.During the six-hour pursuit,the Japanese vessels fired more than 500 rounds.It is reported that Japan fired the first shot.②See Peter Landers,Conflict Shows a Gray Area in Japan Law-Tokyo Weighs Revision to Boost Defense Measures,Asian Wall Street Journal,26 December 2001,p.3.The sinking of the mysterious ship took place within China’s EEZ, some 260 kilometers from China’s territorial sea.③China asks Japan to provide more information about sinking of unidentified ship,BBC Monitoring,23 December 2001.China expressed its regrets for those killed or wounded and was concerned about Japan’s use of military force in the East China Sea.④Boat sinks after being hit by Japanese fire,China Daily,24 December 2001;and China reiterates concern over Japan’s use of force,Kyodo News,25 December 2001.

After the incident,Japan requested to salvage the sunken ship as a necessary step to investigate the whole matter and China gave its consent to Japan’s proposal.According to the spokesman of the Chinese Foreign Ministry,consent was based on the LOS Convention and relevant Chinese domestic laws, and China had the right to monitor the whole salvage.⑤See“Chinese side monitor under the law Japan’s investigation of the sunken ship in the East China Sea”,People’s Daily(in Chinese),30 April 2002,p.4.For the negative impact on normal fishery order and the monetary loss Chinese fishermen sustained due to salvage efforts,Japan agreed to compensate a total of 150,000, 000 yen.⑥The two sides reached the agreement on 27 December 2002 after five rounds of consultation.See http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/chn/gxh/zlb/tyfg/t5905.htm,28 July 2009.

Ⅳ.Dispute in Oil and Gas Exploration and Exploitation

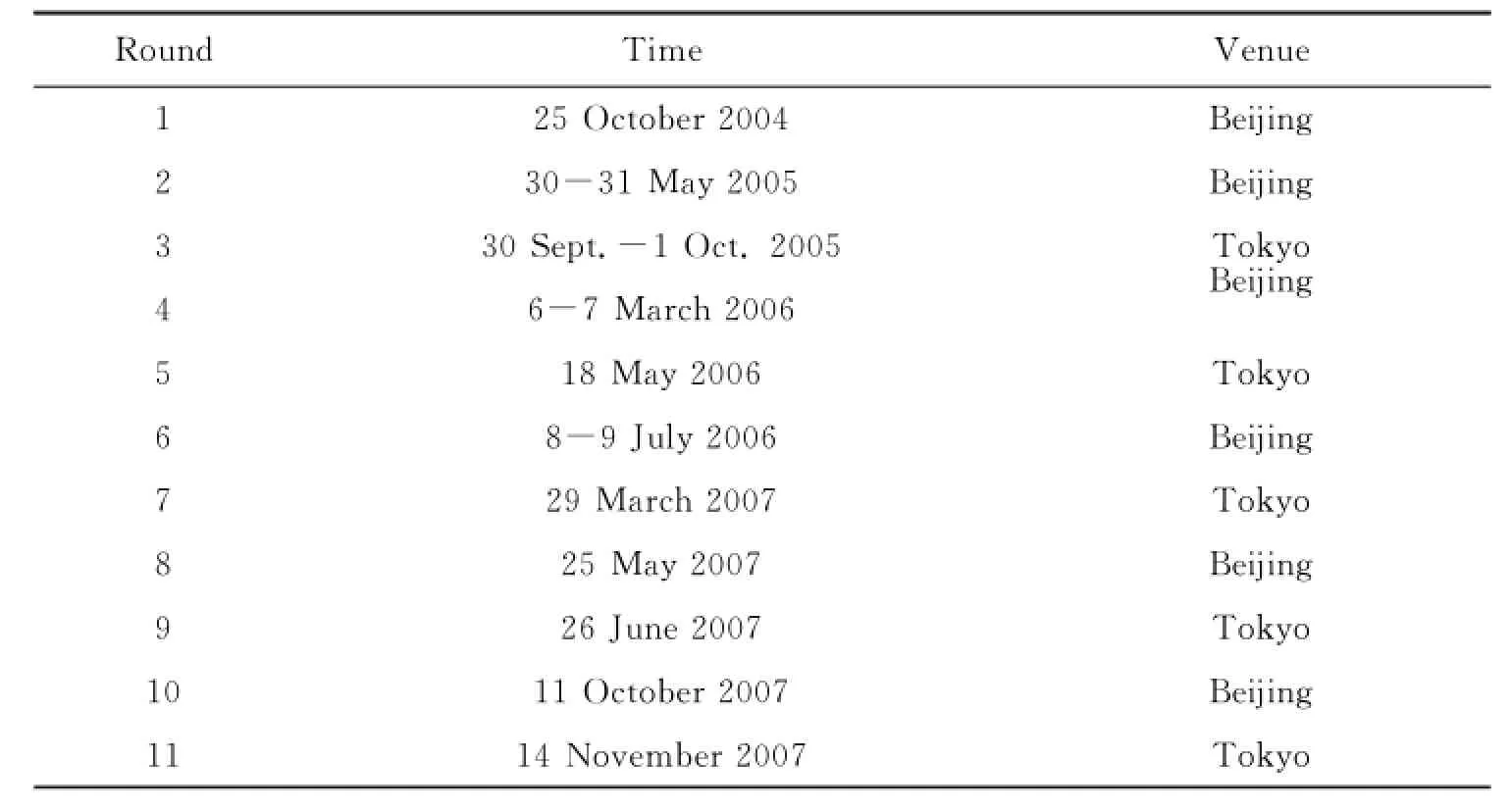

However,more serious issues than scientific research or salvage exist in the East China Sea,such as oil and gas exploration and development.After China began to explore the Chunxiao gas field,Japan expressed its discontent and accused China of encroaching upon Japan’s rights in the East China Sea. The two sides held consultations on 25 October 2004.At the sixth round of consultations in July 2006,the two sides agreed to establish a hotline to dealwith unexpected maritime matters.①China and Japan reached the principle consensus on establishing maritime hotline,available at http://world.people.com.cn/GB/4572649.html,30 August 2006.During the following meeting,China introduced two proposals on joint development in the East China Sea but Japan only considered the one pertaining to the northern sea area.②Japan considers accepting the proposal on joint development in the northern sea area in the East China Sea,15 May 2006,available at http://world.people.com.cn/GB/1029/42354/ 4371017.html,16 May 2006.After 11 rounds of consultations(see Table 1),the two countries finally reached a consensus agreement on 17 June 2008.They pledged to cooperate in the East China Sea and turn it into a sea of peace,cooperation and friendship.A joint development scheme was created and a small patch of joint development zone was demarcated.In addition,China gave permission for Japanese legal persons to participate in the development of Chunxiao Oil and Gas Field in accordance with Chinese laws.③China,Japan reach principled consensus on East China Sea issue,18 June 2008,available at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2008-06/18/content_6774860.htm,13 May 2009.

The conclusion of this agreement is in line with the spirit and provisions of the LOS Convention,which encourages States to work out provisional arrangements including cooperation on joint development pending the settlement of their maritime boundary disputes.

Ⅴ.Issues concerning the Outer Limit of Continental Shelf

Article 76 of the LOS Convention provides the criteria to determine the outer limit of the continental shelf up to 350 nm from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured or 100 nm from the 2,500 metre isobath:

(i)a line delineated by reference to the outermost fixed points at each of which the thickness of sedimentary rocks is at least 1 per cent of the shortest distance from such point to the foot of the continental slope;or

(ii)a line delineated by reference to fixed points not more than 60 nautical miles from the foot of the continental slope.

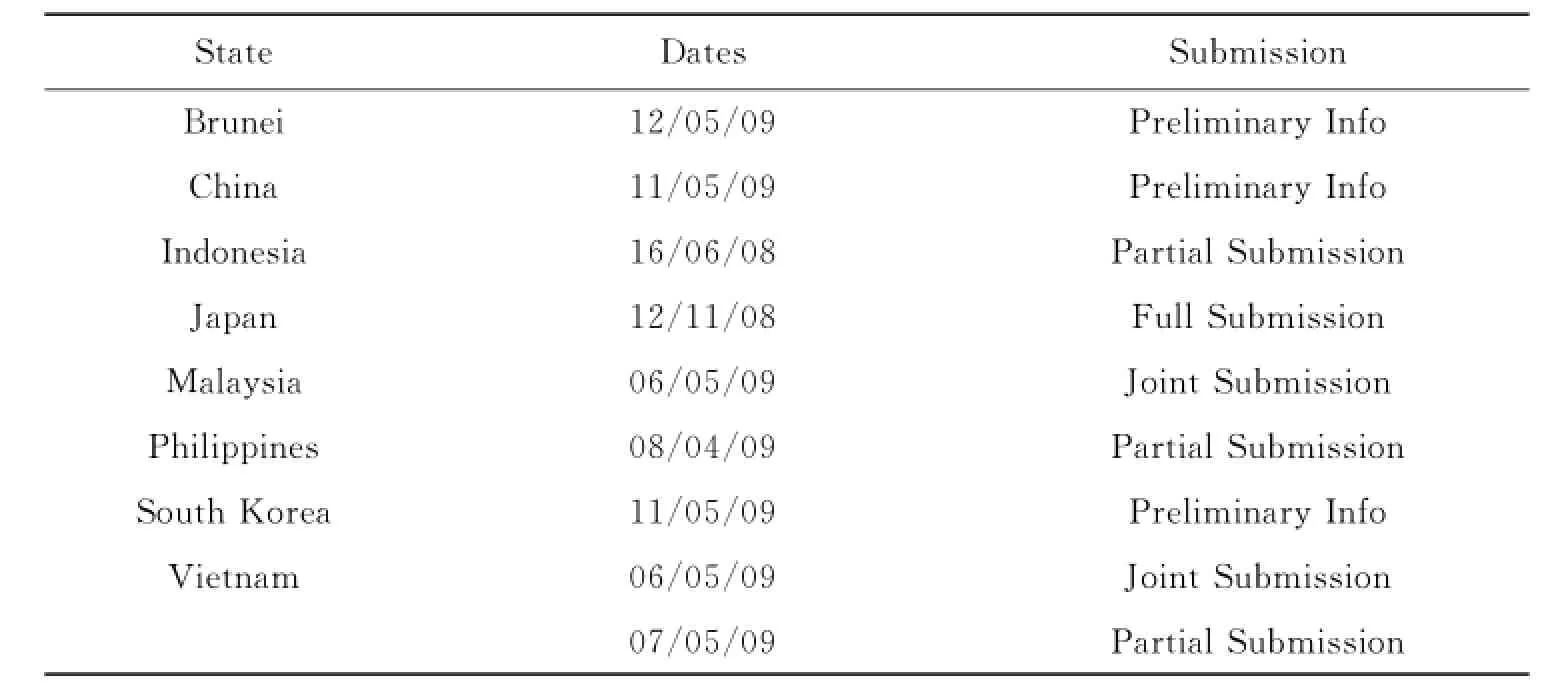

The deadline for any submission from a coastal State that became party tothe LOS Convention before 13 May 1999,on its outer continental shelf to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf was 13 May 2009(for East Asian countries,see Table 2).For all others,the submission deadline is ten years from the date of ratification or accession to the treaty.The Commission considers the data and other material submitted by coastal States concerning the outer limits of the continental shelf in areas where those limits extend beyond 200 nautical miles,and makes recommendations in accordance with Article 76 of the LOS Convention and the Statement of Understanding adopted on 29 August 1980 by the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea.Japan submitted its claim on 12 November 2008.

On 6 February 2009,China lodged its objection to part of the Japanese submission regarding the Oki-no-Tori Shima,which,in China’s view,is in fact a rock that generates no EEZ or continental shelf and requests that the Commission not take any action on the portions extended from that rock.①China’s Objection is available at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_ files/jpn08/chn_6feb09_e.pdf,10 December 2009.South Korea shared the same view as the Chinese.However,the Commission is not a judicial body,thus it lacks the competence to interpret the provisions of the LOS Convention,such as Article 121 of the Convention.②Statement by the Chairman of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf on the progress of work in the Commission,CLCS/64,1 October 2009,available at http:// daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N09/536/21/PDF/N0953621.pdf?Open Element,10 December 2009.Furthermore,if there is a dispute regarding a submission between different countries,the Commission has no mandate to review it.

Ⅵ.Territorial Dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands

The dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands between China and Japan has now become a thorn in the two countries’side,so to speak.Located in the East China Sea,the Diaoyus/Senkakus have a total land area of 7 sq km with the Diaoyudao or Uotsuri Jima being the largest among this group of islands.

As we know,the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue was circumvented in the fishery agreement by providing that both sides respect the current fishing operations in the part of the East China Sea in the north of the PMZ,pay due consideration to the traditional fishing of the other country and the amount of resources available,and not unduly damage the interest of fishing of the other country inthe said area.①Agreed Minutes between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of Japan,11 September 1997.As explained by the Japanese side,the purpose of the fishery agreement was to establish a fishing order between Japan and the PRC and had no direct relationship with the issue of sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands. The territorial waters of the Senkaku Islands are not an area where the agreement applies or would affect its status.②See Nobukatsu Kanehara and Yutaka Arima,New Fishing Order-Japan’s New Agreements on Fisheries with the Republic of Korea and with the People’s Republic of China, Japanese Annual of International Law,vol.42,1999,pp.27-28.At present,the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands are under Japan’s control,but the dispute goes back over a century.③For the official positions of both governments,see The Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands,available at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/senkaku/ senkaku.htm1,4 July 2002;and“The Issue of Diaoyu Islands”,available at http://www. fmprc.gov.cn/eng/3790.html,26 July 2002.There is no immediate prospect that the dispute will be solved in the near future.

Ⅶ.Maritime Boundary Delimitation

The boundary delimitation of the EEZ and continental shelf between China and Japan is very complicated.As we know,Japan has advocated the application of the median line as a delimitation line for the EEZ and the continental shelf with three main reasons:

(1)It woul d be inappropriate if the outer limit of the EEZ remained undecided while delimitation talks failed to reach any agreement.

(2)The traditional position of Japan that delimitation of the EEZ should be made in accordance with the median line principle should be maintained.

(3)It is ap propriate to maintain consistency with the Law on the Provisional Measures related to the Fishery Zone of 1977,which adopted the median line principle.④Toshihisa Takasa,The Conclusion by Japan of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea(UNCLOS)and the Adjustment of Maritime Legal Regime,Japanese Annual of International Law,No.39,1996,p.139.

However,China’s position is different and does not hold the equidistance method to be the only criterion for delimitation.Instead,it has advocated the application of the natural prolongation principle for the delimitation of the continental shelf with Japan.①As is stated,China adheres to the following principles for the delimitation of the continental shelf:(1)application of the concept of natural prolongation;(2)delimitation through negotiation or consultation;and(3)consultation regarding equitable principles taking into account all relevant circumstances.See Wang Tieya,“China and the Law of the Sea”,in Douglas M.Johnston&Norman G.Letalik eds.,The Law of the Sea and Ocean Industry:New Opportunities and Restraints(Honolulu:Law of the Sea Institute,University of Hawaii,1984),p.587.As early as the 1970s,when Japan and South Korea concluded the agreement for joint development in the East China Sea,China sent its strong protest against such a deal on the grounds that it encroached upon the sovereignty of China over its legitimate continental shelf.②For reference,see Wei-chin Lee,Troubles under the Water:Sino-Japanese Conflict of Sovereignty on the Continental Shelf in the East China Sea,Ocean Development and International Law,vol.18(5),1987,pp.585-611.Natural prolongation is quite meaningful for China because,at least in the East China Sea, the continental shelf extending from the mainland is very broad,and China has used the concept of natural prolongation to support its claim to the continental shelf in the East China Sea.Since the general trend in state practice concerning boundary delimitation of the EEZ/continental shelf is towards a single line to delimit the two different and closely associated maritime zones,it is reasonable to wonder whether natural prolongation could still play a significant role in such delimitation.A single but adjusted line may be more practical.

As to the EEZ delimitation,it seems that China will agree to the median line for the two countries.If China insists on natural prolongation for the delimitation of the continental shelf while agreeing to the median line as the line of delimitation of the EEZ,then there would be two different delimitation lines in the East China Sea with Japan;this would give rise to difficulties in law enforcement and the exercise of jurisdiction for both countries.

Nevertheless,some agreements relating to maritime boundary delimitation have been reached between China and Japan.The 1997 Fishery Agreement recognized the undisputed parts of the EEZs in the East China Sea and established a Provisional Measures Zone,a step towards final settlement of the EEZ delimitation.Despite its nature as provisional,the Agreement has narrowed the disputed area in the East China Sea between the two countries.The consensus agreement reached in June 2008 regarding joint development in the East ChinaSea is also relevant to maritime boundary delimitation.

It has to be noted that there is a very important and even critical factor affecting the maritime boundary delimitation,i.e.the dispute over the Diaoyu/ Senkaku Islands.Currently,Japan has maintained a tight control over the islands.As is observed,China did not lodge protests until the very late 1960s and early 1970s.This may affect the effectiveness of its claims to the islands.①See Steven Wei Su,The Territorial Dispute over the Tiaoyu/Senkaku Islands:An Update, Ocean Development and International Law,vol.36,2005,p.55.Nevertheless,the determination of sovereignty over the disputed islands must take many factors into consideration.This can be seen from the recent judicial rulings of the International Court of Justice(ICJ),which awarded islands to the existing occupiers in the cases of the Sovereignty over Pulau Litigan and Pulau Sipadan(Malaysia/Indonesia)and the Sovereignty over Pedra Branca,Mid dle Rocks and South Ledge(Malaysia/Singapore)but transferred the legal title of the Bakassi Peninsula(which had been occupied by Nigeria)to Cameroon in the case of Land and Maritime Boundary between Cameroon and Nigeria.②For details of these cases,see the ICJ website:http://www.icj-cij.org/homepage/index. php?lang=en,5 December 2009.

It is obvious that whoever owns these islands will also gain control over a large area of maritime zones that they generate.Based on the LOS Convention,a small islet can generate a large area of maritime zone around it(12-nm territorial sea,and in some cases 200-nm EEZ from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured).In that case,no country would give up its claims to the disputed islands but would maintain a firm position of asserting sovereignty over them.Slightly complicating the situation is the fact that these territorial claims are intricately connected to nationalism.This can be seen from recent mass protests in China regarding the Diaoyu Islands against Japan.Thus any settlement of these maritime territorial disputes remains a remote possibility.

Ⅷ.Third Party Interests

Maritime issues often affect the interests of third parties.In the East China Sea,China lodged a strong protest against the establishment of a Japan-Korea Joint Development Zone in the East China Sea in the 1970s.Likewise,thebilateral fishery agreement between China and Japan or between Japan and Korea also affected the interests of the third party since they share the same sea area and use the same pool of marine living resources.

When Japan and Korea concluded their new fishery agreement,China considered that the Japan-Korea Fishery Agreement infringed on China’s sovereign rights over its EEZ in the border areas among the three countries and stated that China’s rights and interests in the EEZ and its fishery activities should not be subject to the limitations of that agreement.China maintained that the delimitation of the overlapping area among the three countries should be subject to consultations among the parties concerned,and exclusion of any party from the delimitation negotiations would be a violation of international law.①MF Spokesman expresses that the Japan-Korea Fishery Agreement encroaches on China’s sovereign rights over its EEZ,People’s Daily(in Chinese),23 January 1999.For further reference,see Fan Xiaoli,Comments on the New Japan-Korea Fishery Agreement,Ocean Development and Management(in Chinese),vol.17(1),2000,pp.68-70.Similarly,South Korea also expressed its dissatisfaction with the Sino-Japanese Fishery Agreement by asking China and Japan to explain how they drew the northern-limit line of their joint fishing area.They should have consulted South Korea before reaching the agreement.②See Chi Young Pak,Resettlement of the Fisheries Order in Northeast Asia resulting from the New Fisheries Agreements among Korea,Japan and China,Korea Observer,vol.30 (4),1999,pp.614-615.For another related reference,see Mark J.Valencia and Yong Hee Lee,The South Korea-Russia-Japan Fisheries Imbroglio,Marine Policy,vol.26,2002,pp. 337-343.

On the other hand,it should be realised that the fishery agreements either between China and Japan,or China and South Korea,or Japan and South Korea are bilateral ones.They have limitations and also do not completely cover the areas in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea.Second,because of their bilateral nature,they may affect the interests of a third party as illustrated above in the Japan-Korean Fishery Agreement.Third,bilateral agreements only regulate bilateral relations and not the fishing activities of third parties.This is particularly true where Taiwan is concerned.Finally,many fishery resources in the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea are migratory species belonging to the same marine ecosystem.In that sense,the East Asian seas urgently need a regional and multilateral fishery arrangement to more effectively conserve and manage the fishery resources therein,and the newly concluded bilateral fishery agreements including the Sino-Japanese one could be the basis for such regionalcooperation.

In addition,in May 2009 China and the Republic of Korea both submitted preliminary information regarding their outer continental shelves in the East China Sea to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with relevant provisions of the LOS Convention and other decisions made by the State Parties Conferences on the Law of the Sea.①For details on China’s submission,see http://www.un.org/Depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/preliminary/chn2009preliminaryinformation_english.pdf and on Korea’s submission,see http://www.un.org/Depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/preliminary/kor _2009preliminaryinformation.pdf,17 December 2009.The submission of the preliminary information enables them to make their full submissions at a later time.Since such preliminary information indicates that both China and Korea’s outer continental shelf claims are in the East China Sea,it surely affects the interests of Japan.Furthermore,because the two apparently did not coordinate prior to submission,their respective claims in the East China Sea are conflicting as well.

Ⅸ.Possible Settlement

In international law,there are a number of mechanisms for the settlement of maritime disputes,including such political means as negotiation and consultation,mediation and good offices,conciliation,investigation,and such judicial means as arbitration and international adjudication.Most of them are listed in the Charter of the United Nations.②Article 33,para.1 of the UN Charter.In addition,international organizations, whether global or regional,can play an active role in dispute settlement.Judicial settlement of maritime disputes is usually within the competence of the International Court of Justice(ICJ)and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea(ITLOS).Among East Asian countries,China’s attitude is most worthy of a close observation.China always prefers bilateral negotiation and consultation for dispute settlement between States.In the international arena, China has advocated negotiation as the most practical means of dispute resolution.In practice,China has resolved a number of bilateral disputes between itself and other countries via negotiation and consultation,on border disputes, nationality,etc.

Nevertheless,for the resort of judicial means,China’s attitude is ratherconservative.During the Sino-India border conflict in 1962,China refused India’s proposal to submit the border dispute to arbitration,stating that“the Sino-India border dispute is an important matter concerning the sovereignty of the two countries,and the vast size of more than 100,000 square kilometers of territories.It is self-evident that it can only be resolved through direct bilateral negotiations.It is never possible to seek a settlement from any form of international arbitration”.①See Gao Yanping,International Dispute Settlement,in Wang Tieya ed.,International Law,Beijing:Law Press,1995(in Chinese),pp.611-612.There are some likely reasons behind this passivity: first,China,having suffered tremendously from Western colonization and aggression in history,did not trust the international judiciary centered on the Western legal principles and doctrines;and second,China stood in alignment with other communist countries,holding the perception that the world was in a perpetual state of conflict between capitalist States and socialist States and since the interests and policies of these States were so opposed,it was not possible to resolve any dispute through impartial adjudication.②See Paul R.William,International Law and the Resolution of Central and East European Transboundary Environmental Disputes,Macmillan Press,2000,p.199.

However,after the 1980s,China changed its policy towards international arbitration by consenting to arbitration in treaties China concluded and acceded to,but confined only to economic,trade,scientific,transport,environment,and health areas.In practice China has to evaluate whether such a submission would endanger its national interest and sovereignty,and other factors that might not be in its favor.China’s hesitation in this respect was manifested in its attitude towards the dispute settlement mechanism set forth in the 1997 Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses.During the negotiations,China expressed its concerns over any arrangement for compulsory dispute settlement mechanism.The Chinese representative stated that“China was not opposed to binding procedures,only to the adoption of such procedures without the consent of the parties”.③See UN Doc.A/C.6/51/SR.59(1997),para.3,at 3;cited in Attila Tanzi,“Recent Trends in International Water Law Dispute Settlement”,in International Bureau of the Permanent Court of Arbitration ed.,International Investments and Protection of the Environment:The Role of Dispute Resolution Mechanisms,The Hague:Kluwer Law International,2001,p.139.In other words,China will not accept any compulsory mechanism.

Some conventions require the contracting States to accept compulsory ju-dicial dispute settlement procedures,such as the LOS Convention.Upon the ratification of the LOS Convention,China did not identify which compulsory mechanism it had accepted.Under such circumstances,it was deemed to have accepted the mechanism of arbitration.①Article 287(3)of the LOS Convention provides that“A State Party,which is a party to a dispute not covered by a declaration in force,shall be deemed to have accepted arbitration in accordance with AnnexⅦ”.

Meanwhile,China’s attitude towards the role of international courts in dispute settlement is even more passive.China has usually made a reservation about the clause of judicial settlement by ICJ in the treaties to which China is a party.On 5 September 1972,China formally declared that it did not recognize the Statement of the former Chinese Government on Acceptance of the Compulsory Jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice.In fact,for some time China refused to settle any dispute with other countries through ICJ.②See Gao Yanping,International Dispute Settlement,in Wang Tieya ed.,International Law,Beijing:Law Press,1995(in Chinese),p.612.In recent years,some scholars suggested that China accept international judicial settlement to some degree so as to improve China’s international image.③See Shen Wei,Dispute Settlement Mechanism of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea,Ocean Development and Management(in Chinese),vol.13(3),1996,pp.53-54.On the other hand,as a UN Security Council member,China has nominated judges of Chinese nationality to ICJ as well as to other international courts,even though Chinese judges have had little influence over the judicial process and judgments of the international courts.

In order to be involved in dealing with the world ocean affairs,including the mechanism for dispute settlement stipulated in the LOS Convention and to safeguard its own maritime interest,China ratified the LOS Convention on 15 May 1996,which made it eligible to nominate a candidate to be one of the ITLOS judges.It is to be noted that in August 2006 China made a declaration to exclude certain disputes including those concerning maritime boundary delimitation from compulsory third-party settlement procedures in accordance with Article 298 of the LOS Convention.④The full text is available at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_declarations.htm#China%20after%20ratification,16 December 2009.This was not a surprise and follows China’s long-standing tradition of abstinence from any international judicial body in resolving its disputes.Often when China accedes to or ratifies a treaty, it makes a reservation on the clause concerning compulsory jurisdiction of theICJ.However,the settlement mechanism in the LOS Convention is much more tricky.First,a State has to accept one of four juridical methods.Therefore disputes regarding the application and interpretation of the LOS Convention to which China is a party are subject to arbitration at least,except for those matters to be excluded by the Chinese statement.Second,even if China excludes certain specific disputes,they will still be subject to the third-party conciliation mechanism,which can produce tremendous pressure on the States concerned to find a way of solving their disputes.

Therefore,China’s attitude towards the international judiciary is somewhat ambivalent.On the one hand,as a world power,China would like to play a part in that arena.Yet it lacks sufficient qualified legal experts who to provide adequate services in the international judiciary,though this would presumably benefit its own interests.Furthermore,due to the fact that most judges are from Western developed countries,developing countries including China are doubtful whether the international judiciary can uphold the necessary impartiality and justice.Only when China has cherished enough confidence in that field can it play its due role.Recent domestic legal reform in China may provide some impetus to push China closer to the international rule of law and enhance China’s willingness to resort to the international judiciary for dispute settlement.

In comparison,Japan’s attitude is more active and positive.It accepted ICJ’s compulsory jurisdiction as early as 1958.Accordingly,Japan recognized compulsory jurisdiction“over all disputes”.This statement is very generous, but may exclude disputes“which the parties thereto have agreed or shall agree to refer for final and binding decision to arbitration or judicial settlement”.①See Japan’s Declaration of 15 September 1958,ICJ Yearbook,1994-1995,p.95.As reported,Japan’s attitude towards international adjudication completely transformed after World WarⅡ.It adopted the policy of submitting a dispute to adjudication unless it could be resolved through negotiations.②See K.Yokota,International Adjudication and Japan,Japanese Annual of International Law,vol.17,1973,p.20.In the 1950s, Japan proposed to submit a dispute with Australia concerning Japan’s pearl fishing activities in the Timor and Arafura Seas,situated off the northern coast of Australia beyond its territorial waters but within its continental shelfclaim.①See P.Macalister-Smith,Pearl Fisheries,Encyclopedia of Public International Law,vol. 11,p.257.Since Japan has accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ,if China wishes to use the ICJ in resolving the territorial disputes over the abovementioned islands,it may have some advantages when presenting its case.

Although Japan did not choose a compulsory dispute settlement mechanism under the LOS Convention upon its ratification,it has been a party in three cases before the ITLOS:two concerning prompt release and one requesting provisional measures.The two prompt release cases both involved Japanese vessels detained by Russia in its EEZ for alleged illegal fishing.In the“Hoshinmaru”case,the two parties were not in agreement over the amount of the security bond imposed by the Russian authorities.The Tribunal’s judgment in August 2007 settled the dispute by adjusting this amount.②For details,see http://www.itlos.org/start2_en.html,5 September 2009.In the“Tomimaru”case submitted by Japan in 2007,the Tribunal simply ruled that there was no object on which it needed to be called upon for a decision since the Japanese vessel in question had already been confiscated by the Russian authorities.③For details,see http://www.itlos.org/start2_en.html,5 September 2009.

In the case of Southern Bluefin Tuna(New Zealand/Australia v.Japan), Japan was forced to respond to the case submitted by Australia and New Zealand in July 1999.The two Southern Ocean countries requested the Tribunal to render provisional measures(an interim injunction)to stop Japan’s unilateral experimental fishing of southern bluefin tuna(SBT)in 1999.In its response Japan asked the Tribunal to deny the provisional measures requested by Australia and New Zealand.In Japan’s view,the two countries did not meet the conditions set forth in international law.In August 1999,the Tribunal rendered an order containing several decisions:first,the three countries concerned should not aggravate or extend the dispute and their annual catches should not exceed the annual national allocations at the levels last agreed by the parties. They should refrain from conducting an experimental fishing programme involving the catch of southern bluefin tuna,except with the agreement of the other parties or unless the experimental catch is deducted from its annual national allocation,and resume negotiations without delay with a view to reaching agreement on measures for the conservation and management of southern bluefin tuna.Secondly,each party should submit the initial report to ITLOS and further reports and information upon request.Thirdly,the provisional measures pre-scribed in the order should be notified by the Registrar through appropriate means to all States Parties to the Convention participating in the fishery for southern bluefin tuna.①For details about the case,see http://www.itlos.org/start2_en.html,16 December 2009.

Some existing examples in East Asia may be learned by the countries in question to settle their disputes.There are two recent cases submitted by East Asian countries before the ICJ:the case of Sovereignty over Pulau Litigan and Pulau Sipadan(Malaysia/Indonesia)(1998-2002)and the case on Sovereignty over Pedra Branca,Mid d le Rocks and South Ledge(Malaysia/Singapore)(2003-2008).Both cases concern maritime territorial disputes.In the judgment on Sovereignty over Pulau Litigan and Pulau Sipadan,ICJ granted the disputed islands to Malaysia,while in the latter case,the Court awarded Predra Branca to Singapore and Middle Rocks to Malaysia.②For details on these two cases,see respectively http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index. php?p1=3&p2=3&code=inma&case=102&k=df and http://www.icj-cij.org/ docket/index.php?p1=3&p2=3&code=masi&case=130&k=2b,17 December 2009.

Another case relating to East Asia is the Case Concerning Land Reclamation by Singapore in and around the Straits of Johor(Malaysia v.Singapore).The case was first submitted to the ITLOS in September 2003 by Malaysia requesting the Tribunal to impose provisional measures to stop Singapore’s land reclamation activities-both in the vicinity of the maritime boundary between the two states and areas claimed as territorial waters by Malaysia-pending the decision of the Arbitral Tribunal.③Due to its scarcity of land,Singapore actively carries out land reclamation.According to a statistic,Singapore’s land area increased from 581 km2 in 1966 to 695 km2 in 2003.See Kog Yue-Choong,Environmental Management and Conflict in Southeast Asia:Land Reclamation and Its Political Impact,IDSS Working Paper,No.101(Institute for Defence and Strategic Studies,Nanyang Technological University,Singapore),January 2006,p.7.The Tribunal issued an order in October 2003 prescribing that Malaysia and Singapore should cooperate to establish a group of independent experts to study and prepare an interim report on the subject matter,directing that Singapore should not“conduct its land reclamation in ways that might cause irreparable prejudice to the rights of Malaysia or serious harm to the marine environment,taking especially into account the reports of the group of independent experts”and deciding that“Malaysia and Singapore shall each submit the initial report referred to in article 95,paragraph 1,of the Rules,not later than 9 January 2004 to this Tribunal and to the AnnexⅦarbitral tribunal,unless the arbitral tribunal decides other-wise”(the references to“Art.95,paragraph 1 of Rules”and“AnnexⅦarbitral tribunal”might be superfluous here,not to mention slightly confusing. Consider omitting them and using ellipses in the quote).①Order on the Case Concerning Land Reclamation by Singapore in and around the Straits of Johor(Malaysia v.Singapore):Request for Provisional Measures,ibid.,para 104,at http://www.itlos.org/start2_en.html,17 December 2009.Following ITLOS’s order,the two sides jointly established a group of experts,which submitted its final report to the two sides on 5 November 2004.Based on the report,the two sides reached a resolution on 26 April 2005,agreeing to terminate the case through several arrangements including Singapore’s modification of the final design of the shoreline of its land reclamation,Singapore’s compensation to affected Malaysia fishermen,and the discussion and monitoring of the environmental impacts in the Straits of Johor by the Malaysia-Singapore Joint Committee on the Environment(MSJCE).②See Case Concerning Land Reclamation by Singapore in and around the Straits of Johor (Malaysia v.Singapore):Settlement Agreement(on file with the author).

Ⅹ.Conclusion

In light of the above observations,a few concluding remarks may be made.First,as neighbouring countries maritime encounters and interactions are inevitable between China and Japan,so too are maritime disputes.Second, it can be seen that while maritime cooperation has been carried out between the two sides,there are a number of maritime disputes yet to be resolved.The disputes are embedded in a historical context of frequent maritime interactions between the two nations and have been exacerbated by the new legal regime of the oceans based on the LOS Convention.Third,apparently both sides prefer a solution to their disputes by peaceful means and third party judicial settlement is thus recommended.Finally,as both sides exert their sincere efforts towards the settlement of their maritime and territorial disputes,the East China Sea is expected to become a sea of peace and cooperation,rather than one of conflict and tension.

Table 1:Rounds of Negotiation on the East China Sea Dispute

Table 2:Dates of Submission in East Asia (should it be noted what kind of submissions these are and to whom they were submitted?)

(Editor:DENG Yuncheng; English Editor:Joshua Owens)

*ZOU Keyuan,Harris Professor of International Law,Lancashire Law School,University of Central Lancashire.E-mail:kzou@uclan.ac.uk.

Both countries are major maritime powers in East Asia and keen to uphold or even expand their rights and interests in their adjacent oceans.They both joined the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and enacted accordingly the relevant laws governing the territorial sea,contiguous zone,exclusive economic zone(EEZ)and continental shelf at the domestic level.The extension of national maritime zones inevitably caused tensions and conflicts between neighbouring countries.The East China Sea,where the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands are located,is home to the most salient maritime disputes between China and Japan.In addition,the two sides are at odds over maritime boundary delimitation and offshore oil and gas development in the East China Sea.

This paper attempts to review the recent developments of the maritime relations between China and Japan.While maritime cooperation will be addressed in some detail,the paper will focus more on the maritime disputes between the two sides and aims to suggest possible solutions.