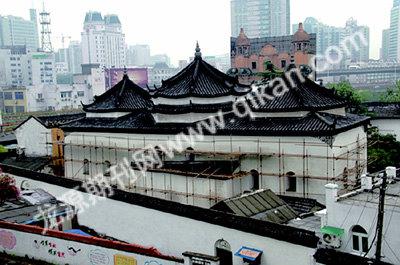

Phoenix Temple,a Hallmark of City’s History

2009-06-05ShaZhou

Sha Zhou

The Phoenix Temple had a few names in the past. After a restoration project during the reign of the Emperor Guangxu of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), it was called the Phoenix Temple because the church looked like a flying phoenix. But the names did not change what it is: it has been a muslin church since the very beginning. It was one of the four major ancient mosques in southeast Chinas coastal areas. The other three are: the Lion Temple in Guangzhou, the Qilin Temple in Quanzhou and the Crane Temple in Yangzhou.

The history of the Phoenix Temple in Hangzhou is closely associated with the friendly exchanges between Hangzhou and the Arabic and Persian areas in ancient times. As early as the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Hangzhou had established trade relations with Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia and Arabic countries. Hangzhou could reach the outside world through the Qiantang River and could reach the vast inland in central and northern China through the Grand Canal which links Hangzhou all the way to todays Beijing. History describes in great detail how Hangzhou was a busy port city and how the shipping channel on the river was carefully maintained.

In the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), Hangzhou was known as the most prosperous city in southeastern China. It functioned as one of the four major port cities of the empire. The shipping and foreign trade became more flourishing when the city became the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) and compass was widely used on ocean-going ships. In the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), trade between Hangzhou and Middle East was more thriving and the city became home to many Arabic and Persian businesspeople. These foreigners were best known for their jewelry shops. A few existing local place names tell the story of their legendary wealth, business and ethnic origins. The west end of Qingtai Street, where the flourishing ancient muslin community once resided, still has some muslin people live there today.

Marco Polo, Odorico da Pordenone, Ibn Battuta, three of the four great world travelers in the Middle Ages, visited Hangzhou in the years of the Yuan Dynasty. Their separate travelogues mentioned that Hangzhou had muslin residents. Ibn Battuta describes in great detail the extravagant hospitality he received during his 15-day visit to Hangzhou in the summer of 1346. It would take a person three days to travel along the city wall and go through the six regions of the city. The travelogue also describes muslin mosques, religious ceremonies, architecture, muslin disciples, banquets, a lake tour, music, food, ornately decorated pleasure boats on the lake.

With deep eyes and high foreheads, the people from Arab and Persia looked different from Chinese local residents. The foreigners adhered to their own lifestyle. Their weddings and burials were different, too. History records a wedding that ended up in tragedy. The wedding was so outlandish that local residents flocked to visit the house. Some local residents were so curious that they climbed the walls and trees to peep in. The house crashed and killed the bride and the bridegroom and some important guests.

The muslins also had their separate cemetery in Hangzhou. Their tombs grew in great numbers in the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing dynasties that the cemetery measured nearly 70,000 m2 once upon a time. In the cemetery were also tombs of high-ranking muslins such as princes and elders. Their tombstones were marked in Arabian, Chinese and Persian languages. In a large-scale grave relocation in 1955, more than 14,600 remains from the cemetery were relocated and reburied.

Not all muslins stayed away from the culture of their new hometown. Some adapted so well that they became celebrated scholars. Marriages between immigrant families and local families took place frequently. General merchandises such as walking sabers, pigments, food, spices, glass bottles, which were originally for muslin immigrants, became popular with local residents in Hangzhou.

The muslins that came to Hangzhou from the west were from different tribes. They were ancestors of the muslin population in Hangzhou. Like other ethnic groups, they made their contribution to the material prosperity and social progress of Hangzhou.

The mosque was rebuilt in the Yuan Dynasty by a muslin imam. It stood in an architectural style seen in western Asia in ancient times. In 1341, the prayer hall underwent a major refurbishment and became the largest mosque in Hangzhou and has remained so since then. The gilded scripture of Quran on the walls of the prayer hall was made in 1451 in a refurbishment project. The temple experienced a major refurbishment in 1670 and 1892 respectively in the Qing Dynasty. It has been called the Phoenix Temple since 1892. The temple gate and a five-story wood tower were dismantled in 1929, making room for a municipal project. A hall was added to the temple in 1953. The temple has seen a few more refurbishment projects since 1953. The present temple measures 2,600 m2 in the total area and 2,203 m2 in floor space. Two stone steles in the temple relate in Chinese the two refurbishment projects made in the Ming Dynasty and the Qing Dynasty. There are also 20 plus tombstones with inscriptions in the Arabic and Persian languages. Some original building components of the dismantled tower are still kept in tact at the temple.

The temple was placed under protection of the Zhejiang Provincial Government in 1961. It has been under national protection since 2001. At present, the temple is under a major restoration as part of the Zhongshan Road Refurbishment Project. The dismantled tower will be restored. □