微生物除草剂的研究进展

2024-06-16朱桓吾邓炜邓金奇罗坤

朱桓吾 邓炜 邓金奇 罗坤

摘要:杂草对农业生产构成了巨大的威胁,对农业经济带来了深远的影响。过度依赖化学除草剂的现象引发了大量的抗药性杂草种群出现,这不仅增加了除草剂的使用频率和用量,还会引发恶性循环。通过对现有文献和研究数据的分析,阐述了微生物除草剂的分类及其对目标杂草物种的生物除草活性和特异性。微生物除草剂凭借其延缓杂草产生耐药性、对生态环境影响较小、安全性高和资源充足等独特优势,有望满足可持续农业发展的需求。本文进一步分析了国内外微生物除草剂的发展现状及面临的限制因素,并展望其未来的发展方向和利用趋势。

关键词:微生物除草剂;植物病原菌;生物防治

中图分类号:S482.4 文献标志码:A

Research Status and Prospect of Microbial

Herbicides

Abstract: Weeds posed a great threat to agricultural production and had far-reaching consequences for the agricultural production. Overreliance on chemical herbicides had resulted in large populations of resistant weed population, which not only increased the frequency and dosage of herbicides, but also triggered a vicious cycle. By analyzing current literature and research, this paper outlined the classification of microbial herbicides, and described their bioherbicidal activity and specificity against target weed species. Microbial herbicides were expected to fulfill the needs of sustainable agriculture development due to their unique advantages such as delaying the development of resistance in weeds, less ecological impact, high safety and sufficient resources. This paper further analyzed the current development status of microbial herbicides at home and abroad and the constraints they were facing and anticipated their future development direction and utilization trends.

Keywords: Microbial herbicides; phytopathogen; biological control

杂草对农作物的生产构成了极大的威胁,并对农业经济造成了重大的损失。据文献记载,我国田园杂草种类有1400多种,其中严重危害的杂草种类高达130多种,包括37种恶性杂草和96种区域性恶性杂草,每年由杂草而造成的粮食损失达300万t[1]。近年来,化学除草剂在有效控制各类杂草的同时,也极大地降低了工人的劳动强度。然而,随着化学除草剂的广泛使用,其缺点也越来越明显,如造成环境污染、易致人畜中毒等[2]。大量使用化学除草剂也导致杂草抗药性的出现,进一步导致使用化学除草剂的频率和使用次数增加,从而陷入恶性循环。寻找更加安全、高效的除草剂和施用方式,是目前我国除草剂发展的主要趋势。微生物除草剂具有延缓杂草产生耐药性,对生态环境负效应较低,安全性较高,资源丰富等特点,能满足农业可持续发展的需要[3,4]。

1 微生物除草剂的类型及其研究利用现状

人们尝试利用微生物,特别是利用植物病原菌和它所产生的天然生物活性物质来研制新型除草剂。微生物来源的除草剂分为两大类[5],一类是直接利用活体微生物感染杂草,导致杂草发病和死亡;第二类是通过微生物发酵产生的次生代谢物和毒素控制杂草的生长。

1.1 活体微生物除草剂

活体微生物除草剂具有很多化学除草剂无法比拟的优势,如微生物资源的种类繁多,生产周期短,生长迅速,对人、畜、天敌等非标靶生物安全性较高,对环境无污染,从寄主杂草中分离出的病原菌通常对宿主植物有较高的种间特异性和较高的选择性。活体微生物除草剂在国内外已成为一个热门的研究领域。据报道,目前发现的具有除草潜力的微生物种类有真菌、细菌、病毒等。

1.1.1 真菌微生物除草剂

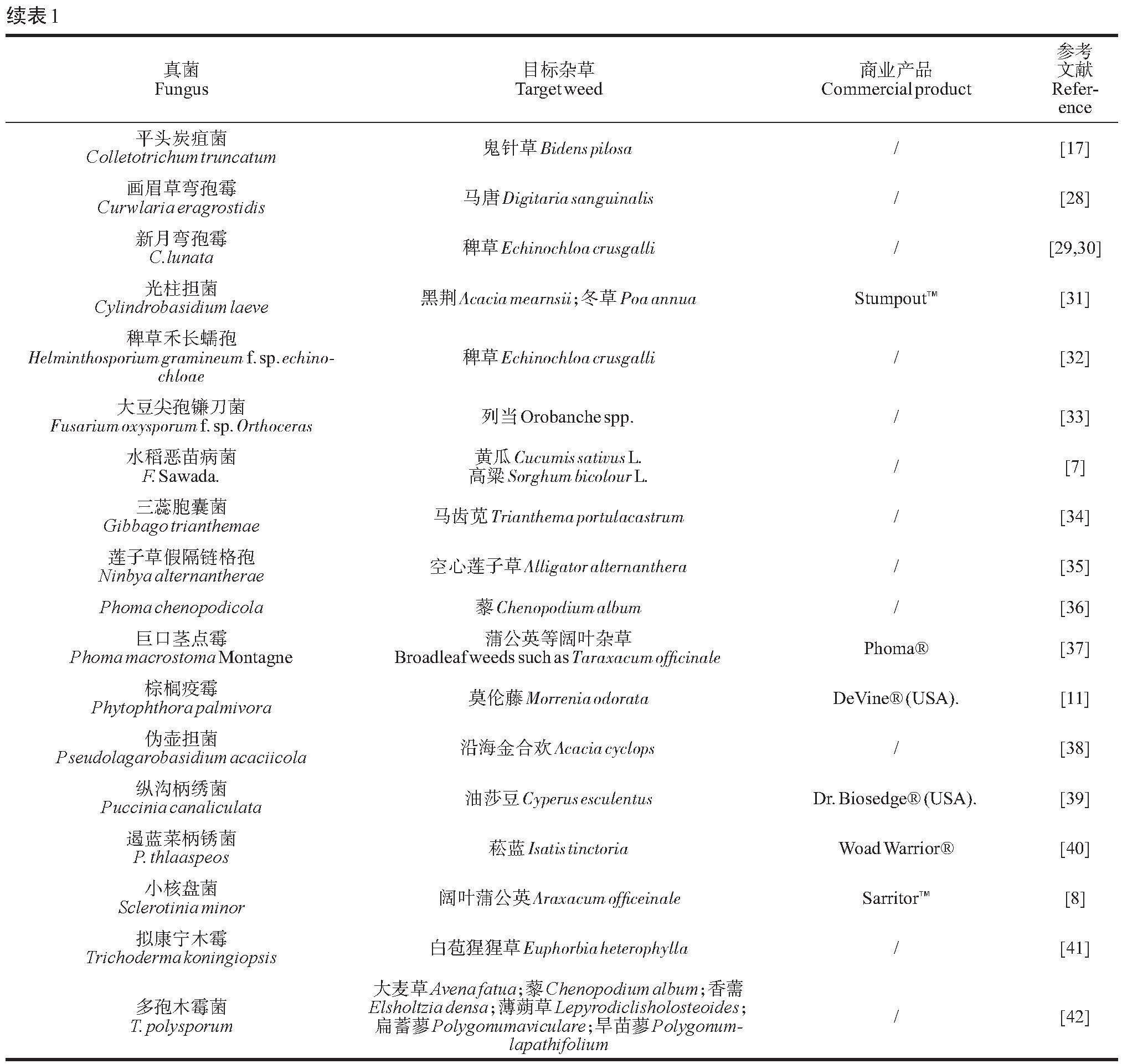

迄今为止,已有40个属80余种真菌具有被开发为微生物除草剂的潜力[6]。主要集中在以下几个属中:镰孢菌属(Fusarium)[7]、链格孢菌属(Alternaria)[8]、尾孢霉属( Cercospora)[9]、炭疽菌属(Coletotrichum)[10]、疫霉属(Phytophthora)[11]、柄锈菌属(Puccinia)[12]、壳单孢菌属(Ascochyta)[13] 、核盘菌属(Sclerotinia)[14] 和弯孢霉属(Curvularia)[15]等。文献表明,炭疽菌属的真菌在微生物除草剂中使用最多,并生产了几种除草剂:BioMal?(C. gloeosporioides f. sp. malvae)[16–18],Collego?/LockDown?(C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene)[16],鲁保1号和鲁保2号(C. gloeosporioides)[10],Velgo?(C. coccodes)[19]。

国内最早用于杂草防治的微生物制剂研发于1963年,名为“鲁保一号”。这种制剂可以有效的防控菟丝子(Cuscuta chinensis Lam.),是我国首个被大规模应用的微生物除草剂[20]。近年来,随着国家各有关部门和科研单位的高度关注,我国微生物除草剂研发取得了一系列的成果(表1)。

1.1.2 细菌微生物除草剂

研究表明,多数用于开发微生物除草剂的细菌菌株能产生毒素,它们主要是革兰氏阳性菌,如假单胞菌属、欧文氏菌属、黄单胞菌属,但也有少数革兰氏阴性菌如链霉菌属、棒状杆菌属,还有一些是非荧光假单胞菌属[43]。美国的科学家从7种杂草的根际土壤中分离出了来自9个属的细菌,研究发现,其中非荧光假单胞菌(Non-fluorescent Pseudomonas)和草生欧文氏菌(Erwinia herbicola)在除草方面表现出了较强的能力[44];加拿大的研究人员从草原土壤中分离出上千种的根际病原细菌,并将其用于防治杂草[45];日本研究人员分离出的一种可引起早熟禾枯萎病的黑腐病菌(Xanthomonas campestris pv. poae)在日本已被开发成微生物除草剂,名称为 Camperico?[46]。近年来,国内的科研人员也将细菌作为一种重要的微生物除草剂的来源。但汉斌等[47]从马唐和稗草的根中分离出792株假单孢菌和515株欧文氏菌,其中欧文氏菌(Erwinia sp.)S7菌株对狗尾草的种子萌发具有明显的抑制作用。史延茂等[48]从马唐病原菌中分离出一株色杆菌(Chromobacerium)S-4,该菌可产生红色素,对马唐种子萌发和根生长分别有93%和85%的抑制率。

1.1.3 病毒微生物除草剂

病毒微生物除草剂最成功和最有前途的来源之一是烟草轻绿花叶病毒(Tobacco mild green mosaic virus)[49]。这种病毒在防控毛果茄(Solanum viarum Dunal)方面显示出很高的成功率。这是因为它能引起植物局部坏死和过敏性反应,使植物在20~50 d内死亡[49,50]。此外,阿鲁藤花叶病毒(Araujia mosaic virus)也被认为是一种潜在的微生物除草剂,可引起飞蛾草(Passiflora cupiformis Mast.)叶片扭曲,导致植物死亡[51]。

1.2 微生物的代谢产物除草剂

在利用微生物代谢物研制除草剂方面,日本的研究人员将微生物产物双丙氨膦(Bilanafos)成功转化为商品除草剂,其是从土壤中分离的链霉菌所产生的代谢产物合成。AAL毒素(AAL-toxin)是由ABBAS等发现的一种感染番茄植株的链格孢(Altemaria altemata)代谢产物,其被证实为一种高效的植物毒素[52]。此外,研究人员还发现一些具有除草活性微生物的代谢产物,包括草菌素(Herbicidin)、绿僵菌素(Destruxin E)、杆孢菌素(Roridins)、疣孢菌素(Verucarins)等[53,54]。

在我国,南京农业大学杂草研究室的万佐玺等通过对紫茎泽兰病害的研究,成功地分离并筛选出了一种紫茎泽兰天然致病的链格孢菌菌株(Alternaria alternata(Fr.)Keissler),研究中发现水花生、鸭跖草、火柴头、酢浆草等难以防除的杂草对该菌产生的毒素极敏感[55]。张金林等[56]发现,葱叶枯病菌毒素对禾本科杂草的种子萌发有很强的抑制作用,对马唐的防效也与百草枯相近。姜述君等[57]从狭卵链孢杆菌AAEC0523中提取了一种淡黄色的油性毒液,该毒液能有效地抑制稗草的种子发芽和幼苗的生长,是一种极具发展前景的微生物源除草剂。上述研究工作,拓宽了国内微生物代谢产物的研究领域范围,开拓了新的应用方向。

2 微生物除草剂的作用机制

活体微生物除草剂利用菌丝侵入寄主组织,产生毒素致使杂草病变,进而影响杂草的正常生理状态,实现控制杂草种群的目标。活体微生物除草剂主要作用于植物体内的敏感分子靶标,而这些靶标与微生物代谢产物除草剂的分子靶点基本不相同。微生物代谢产物除草剂一般利用植物病原菌作为制作除草剂的材料并人为利用以产生大量的发酵产物。这些物质通常通过液体喷雾或固体颗粒接种到目标寄主上,然后渗透到植物中[11,58]。研究显示,当微生物的代谢产物除草剂进入植物体内,会产生淀粉酶、纤维素酶、木质素酶、果胶酶、肽酶、磷脂酶或蛋白酶等,这些酶有助于降解细胞壁、脂膜和蛋白质,使得毒素更容易进入杂草体内[59]。

寄主杂草被微生物除草剂作用后可引起几种生理代谢上的变化:降低细胞活性、酶和激素的功能,从而导致营养吸收减少;光合作用和膜渗透性失调;抑制种子发芽和发育[59–61]。减少养分的吸收会影响叶绿体的发育并导致萎缩,而植物激素的变化会导致抑制赤霉素途径的酚类化合物合成,增加赤霉酸、茉莉酸和水杨酸的积累[59,61]。这些化合物的积累可以改变植物的光合速率,增加氧化应激,影响气孔的关闭,降低植物的生长。

3 微生物除草剂应用的限制因素

对微生物除草剂的评价,主要从有效性和专一性两个角度来进行。有效性指的是微生物除草剂的防治效果,主要是对杂草的控制水平、控制速度、操作难易程度[6]等,其防治效果同时与周围的环境因素有着很大的联系。专一性指的是对寄主的选择性。一般情况下,微生物除草剂的选择性更高,对同类植物的毒性也不同,具体应用时要根据不同的作物需要来选择,保障其安全性[62]。

据报道,仅在2016年,全球微生物除草剂市场份额为12.8亿美元,随着该领域的持续发展,预计到2024年其市场份额将进一步增加到41.4亿美元[63],尽管这一领域的进步是显而易见的,但仍有一些在应用上的挑战,这些问题可能会阻碍其取得广泛的成功[64,65]。环境条件是限制微生物除草剂开发应用的诸多因素之一。据相关研究报道,这些因素包括湿度、土壤类型、温度和紫外线以及水供应量[66]。由于不同地区存在气候变化,杂草将不可避免地出现结构和生理上的变化和进化适应性。另外,困扰微生物除草剂的发展还有以下问题:目前还没有一个关于微生物除草剂生产工艺的统一标准;许多微生物除草剂靶标单一、推广和规模化应用受限;活性物质不稳定、菌株易发生突变、致病力下降、制剂处理难度大等[67,68]。这些都表明了微生物除草剂的开发需要多学科交叉运用,以满足未来微生物除草剂的生产利用的需要。

4 展望

随着社会对绿色农业认识的深入,公众对控草策略的期望和需求发生了一定的变化。以往,控草工作主要侧重于防除杂草以确保农作物的产量;而现今,关注焦点已转向更综合、协调且可持续的管理方式。这种方式强调通过管理杂草生长动态,来维持整体的经济阈值在一个可接受的水平,从而推动农业的可持续发展。在这其中,微生物除草剂展现出作为有效的杂草生物防治剂的巨大潜力。相较于传统除草剂,微生物除草剂在控制杂草方面展现出多项优势:微生物除草剂能够应用于对传统除草剂产生抗性的杂草种类,微生物除草剂在特定环境中展示出高度的宿主特异性;相比传统化学合成除草剂,微生物除草剂更加环保,具有更低的毒性。但微生物除草剂的开发应用及商业化过程通常漫长且复杂,涉及病理学、生态学、遗传学、经济学及供应链管理等领域。为了有效推进这一过程,可能需要持续的研究和关注以下几个方面:优化商品化流程;在真菌、细菌或病毒中寻找更适宜的控草生物源,用以开发新产品;深入研究不同微生物除草剂的作用机制;评估不同环境条件对其控草活性的影响。

参考文献

[1] 李香菊. 近年我国农田杂草防控中的突出问题与治理对策[J]. 植物保护, 2018, 44(5): 77-84.

[2] GREEN J M. Current state of herbicides in herbicide-resistant crops[J]. Pest Management Science, 2014, 70(9): 1351-1357.

[3] de SOUZA BARROS V M, PEDROSA J L F, GON?ALVES D R, et al. Herbicides of biological origin: A review[J]. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology, 2021, 96(3): 288-296.

[4] CAMARGO A F, BONATTO C, SCAPINI T, et al. Fungus-based bioherbicides on circular economy[J]. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 2023, 46(12): 1729-1754.

[5] PERUZZI A, FONTANELLI M, FRASCONI C. Current trends for a modern, integrated, and sustainable approach to weed management[J]. Agronomy, 2023, 13(9): 2364.

[6] 陈世国, 强胜. 生物除草剂研究与开发的现状及未来的发展趋势[J]. 中国生物防治学报, 2015, 31(5): 770-779.

[7] DANIEL J J Jr, ZABOT G L, TRES M V, et al. Fusarium fujikuroi: A novel source of metabolites with herbicidal activity[J]. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, 2018, 14: 314-320.

[8] ANEJA K R, KUMAR V, JILOHA P, et al. Potential bioherbicides: Indian perspectives[M]//Salar R, Gahlawat S, Siwach P, et al. Biotechnology: Prospects and Applications. New Delhi: Springer, 2013: 197-215.

[9] KNIGHT N L, VAGHEFI N, KIKKERT J R, et al. Alternative hosts of Cercospora beticola in field surveys and inoculation trials[J]. Plant Disease,2019, 103(8): 1983-1990.

[10] NANDHINI C, GANESH P, YOGANATHAN K, et al. Efficacy of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, potential fungi for bio control of Echinochloa crus-galli (Barnyard grass)[J]. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics, 2019, 9(6-s): 72-75.

[11] CORDEAU S, TRIOLET M, WAYMAN S, et al. Bioherbicides: Dead in the water? A review of the existing products for integrated weed management[J]. Crop Protection, 2016, 87: 44-49.

[12] BEAN D W, GLADEM K, ROSEN K, et al. Scaling use of the rust fungus Puccinia punctiformis for biological control of Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop.): First report on a U.S. statewide effort[J]. Biological Control, 2024, 192: 105481.

[13] PENG Y, LI S J, YAN J, et al. Research progress on phytopathogenic fungi and their role as biocontrol agents[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2021, 12: 670135.

[14] ABU-DIEYEH M H, WATSON A K. Grass overseeding and a fungus combine to control Taraxacum officinale[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2007, 44(1): 115-124.

[15] KRUPSKA J, WATSON A K. Curvularia eragrostidisisolates (Dematiaceae) for biocontrol of crabgrass (Digitaria spp.) in Canada[J]. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2021, 31(9): 924-950.

[16] BOWERS R C. Commercialization of collego?–an industrialist's view[J]. Weed Science, 1986, 34(S1): 24-25.

[17] VIEIRA B S, DIAS L V S A, LANGONI V D, et al. Liquid fermentation of Colletotrichum truncatum UFU 280, a potential mycoherbicide for beggartick[J]. Australasian Plant Pathology, 2018, 47(3): 277-283.

[18] MORTENSEN K. The potential of an endemic fungus, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, for biological control of round-leaved mallow (Malva pusilla) and velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti)[J]. Weed Science, 1988, 36(4): 473-478.

[19] ANDERSEN R N, WALKER H L. Colletotrichum coccodes: A pathogen of eastern black nightshade (Solanum ptycanthum)[J]. Weed Science,1985,33(6): 902-905.

[20] 高昭远, 干静娥. 菟丝子的生物防除: “鲁保一号” 的研究进展[J]. 生物防治通报, 1992, 8(4): 173-175.

[21] BOYETTE C D. Biocontrol of three leguminous weed species with Alternaria cassiae[J]. Weed Technology, 1988, 2(4): 414-417.

[22] WEAVER M A, HOAGLAND R E, BOYETTE C D, et al. Taxonomic evaluation of a bioherbicidal isolate of Albifimbria verrucaria, formerly Myrothecium verrucaria[J]. Journal of Fungi, 2021, 7(9): 694.

[23] BAILEY K L, BOYETCHKO S M, L?NGLE T. Social and economic drivers shaping the future of biological control: A Canadian perspective on the factors affecting the development and use of microbial biopesticides[J]. Biological Control, 2010, 52(3): 221-229.

[24] BUTT T M, COPPING L G. Fungal biological control agents[J]. Pesticide Outlook, 2000, 11(5): 186-191.

[25] HODGSON R H, WYMORE L A, WATSON A K, et al. Efficacy of Colletotrichum coccodes and thidiazuron for velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti) control in soybean (Glycine max)[J]. Weed Technology, 1988, 2(4): 473-480.

[26] BOYETTE C D, HOAGLAND R E, STETINA K C. Extending the host range of the bioherbicidal fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f.sp.aeschynomene[J]. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2019, 29(7): 720-726.

[27] 朱秦. 胶孢炭疽菌作为防除波斯婆婆纳的生物除草剂产业化相关技术的研究[D]. 南京: 南京农业大学, 2003.

[28] ZHU Y Z, QIANG S. Isolation, pathogenicity and safety of Curvularia eragrostidis Isolate QZ-2000 as a bioherbicide agent for large crabgrass(Digitaria sanguinalis)[J]. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2004, 14(8): 769-782.

[29] 韦韬, 李静, 倪汉文. 稗草生防菌新月弯孢菌Culvularia lunata菌株J15(2)的安全性和致病力[J]. 植物保护学报, 2011, 38(1): 81-85.

[30] 钟加日, 刘璐, 曾颖, 等. 稗草生防菌NX2A的鉴定、安全性及对稗草的致病条件[J]. 南方农业学报, 2022, 53(2): 469-476.

[31] GREEN S. A review of the potential for the use of bioherbicides to control forest weeds in the UK[J]. Forestry, 2003, 76(3): 285-298.

[32] 李新, 谢明, 谭万忠, 等. 杂草生防真菌的研究进展[J]. 中国生物防治, 2009, 25(1): 83-88.

[33] NAZER KAKHAKI S H, MONTAZERI M, NASERI B. Biocontrol of broomrape using Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. orthoceras in tomato crops under field conditions[J]. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2017, 27(12): 1435-1444.

[34] F?LIX-GAST?LUM R, VALDEZ-LEYVA A B, FIERRO-CORONADO R A, et al. First report of stem blight and leaf spot in horse purslane caused by Gibbago trianthemae in Sinaloa, Mexico[J]. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 2021, 43(3): 431-438.

[35] 聂亚锋, 刘长河, 李庆辉, 等. 莲子草假隔链格孢SF-193固体发酵培养基的筛选及其对空心莲子草的控制效果[J]. 生物安全学报, 2011, 20(4): 337-343.

[36] CIMMINO A, ANDOLFI A, ZONNO M C, et al. Chenopodolin: A phytotoxic unrearranged ent-pimaradiene diterpene produced by Phoma chenopodicola, a fungal pathogen for Chenopodium album biocontrol[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2013, 76(7): 1291-1297.

[37] TODERO I, CONFORTIN T C, LUFT L, et al. Formulation of a bioherbicide with metabolites from Phoma sp[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2018, 241: 285-292.

[38] KOTZ? L J D, WOOD A R, LENNOX C L. Risk assessment of the Acacia cyclops dieback pathogen, Pseudolagarobasidium acaciicola, as a mycoherbicide in South African strandveld and limestone fynbos[J]. Biological Control, 2015, 82: 52-60.

[39] PHATAK S C, SUMNER D R, WELLS H D, et al. Biological control of yellow nutsedge with the indigenous rust fungus Puccinia canaliculata[J]. Science, 1983, 219(4591): 1446-1447.

[40] BAILEY K L. The bioherbicide approach to weed control using plant pathogens[G] // ABROL D P. Integrated Pest Management: Current Concepts and Ecological Perspective. San Diego: Academic Press, 2014: 245-266.

[41] REICHERT J?NIOR F W, SCARIOT M A, FORTE C T, et al. New perspectives for weeds control using autochthonous fungi with selective bioherbicide potential[J]. Heliyon, 2019, 5(5): e01676.

[42] ZHU H X, MA Y Q, GUO Q Y, et al. Biological weed control using Trichoderma polysporum strain HZ-31[J]. Crop Protection, 2020, 134: 105161.

[43] KREMER R J, BEGONIA M F, STANLEY L, et al. Characterization of rhizobacteria associated with weed seedlings[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1990, 56(6): 1649-1655.

[44] 冀营光, 邱健, 李承光, 等. 细菌除草剂的发展现状与展望[J]. 生物技术, 2006, 16(1): 88-90.

[45] BOYETCHKO S M. Principles of biological weed control with microorganisms[J]. HortScience, 1997, 32(2): 201-205.

[46] BOYETTE C D, HOAGLAND R E. Bioherbicidal potential of Xanthomonas campestris for controlling Conyza canadensis[J]. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2015, 25(2): 229-237.

[47] 但汉斌, 陈永强, 魏雪生, 等. 从杂草DRB中筛选微生物除草剂的研究[J]. 微生物学通报, 2002, 29(4): 5-9.

[48] 史延茂, 黄亚丽, 董超, 等. 细菌除草剂色杆菌属S-4马唐致病菌除草活性评估[J]. 农药, 2006, 45(11): 782-784.

[49] DIAZ R, MANRIQUE V, HIBBARD K, et al. Successful biological control of tropical soda apple (Solanales: Solanaceae) in Florida: A review of key program components[J]. Florida Entomologist, 2014, 97(1): 179-190.

[50] CHARUDATTAN R, HIEBERT E, CURREY W, et al. Design and testing of field application tools for a bioherbicide with a plant virus as active ingredient[J]. Weeds, 2020, 5(2): 34-45.

[51] ELLIOTT M S, MASSEY B, CUI X, et al. Supplemental host range of Araujia mosaic virus, a potential biological control agent of moth plant in New Zealand[J]. Australasian Plant Pathology, 2009, 38(6): 603-607.

[52] ABBAS H K, TANAKA T, DUKE S O, et al. Susceptibility of various crop and weed species to AAL-toxin, a natural herbicide[J]. Weed Technology, 1995, 9(1): 125-130.

[53] DUKE S O, PAN Z Q, BAJSA-HIRSCHEL J, et al. The potential future roles of natural compounds and microbial bioherbicides in weed management in crops[J]. Advances in Weed Science, 2022, 40(spe1): e020210054

[54] BENDEJACQ-SEYCHELLES A, GIBOT-LECLERC S, GUILLEMIN J P, et al. Phytotoxic fungal secondary metabolites as herbicides[J]. Pest Management Science, 2024, 80(1): 92-102.

[55] 万佐玺, 强胜, 徐尚成, 等. 链格孢菌的产毒培养条件及其毒素的致病范围[J]. 中国生物防治, 2001, 17(1): 10-15.

[56] 张金林, 董金皋, 樊慕贞, 等. 葱叶枯病菌Stemphylium botryosum毒素的分离与除草活性研究[J]. 农药学学报, 2001, 3(2): 60-66.

[57] 姜述君, 范文艳, 鞠世杰, 等. 狭卵链格孢菌株AAEC05-3及其毒素对稗草的致病性[J]. 植物保护学报, 2007, 34(3): 283-288.

[58] HARDING D P, RAIZADA M N. Controlling weeds with fungi, bacteria and viruses: A review[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2015, 6: 659.

[59] XIE C J, WANG C Y, WANG X K, et al. Proteomics-based analysis reveals that Verticillium dahliae toxin induces cell death by modifying the synthesis of host proteins[J]. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 2013, 79(5): 335-345.

[60] TALUKDER M R, ASADUZZAMAN M, TANAKA H, et al. Application of alternating current electro-degradation improves retarded growth and quality in lettuce under autotoxicity in successive cultivation[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2019, 252: 324-331.

[61] LEE S M, RADHAKRISHNAN R, KANG S M, et al. Phytotoxic mechanisms of bur cucumber seed extracts on lettuce with special reference to analysis of chloroplast proteins, phytohormones, and nutritional elements[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2015, 122: 230-237.

[62] HASAN M, AHMAD-HAMDANI M S, ROSLI A M, et al. Bioherbicides: An eco-friendly tool for sustainable weed management[J]. Plants, 2021, 10(6): 1212.

[63] ROBERTS J, FLORENTINE S, FERNANDO W G D, et al. Achievements, developments and future challenges in the field of bioherbicides for weed control: A global review[J]. Plants, 2022, 11(17): 2242.

[64] HASAN M, MOKHTAR A S, ROSLI A M, et al. Weed control efficacy and crop-weed selectivity of a new bioherbicide WeedLock[J]. Agronomy, 2021, 11(8): 1488.

[65] DiTOMASO J M, van STEENWYK R A, NOWIERSKI R M, et al. Addressing the needs for improving classical biological control programs in the USA[J]. Biological Control, 2017, 106: 35-39.

[66] SINDHU S S, KHANDELWAL A, PHOUR M, et al. Bioherbicidal potential of rhizosphere microorganisms for ecofriendly weed management [G] //MEENA V S. Role of rhizospheric microbes in soil. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2018: 331–376.

[67] MORIN L. Progress in biological control of weeds with plant pathogens[J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2020, 58: 201-223.

[68] 叶非, 冯理. 微生物除草剂的研究与应用进展[J]. 东北农业大学学报, 2010, 41(4): 139-143.