P-aminobenzoic acid promotes retinal regeneration through activation of Ascl1a in zebrafish

2024-02-11MeihuiHeMingfangXiaQianYangXingyiChenHaiboLiXiaoboXia

Meihui He, Mingfang Xia, Qian Yang, Xingyi Chen, Haibo Li,*, Xiaobo Xia,*

Abstract The retina of zebrafish can regenerate completely after injury.Multiple studies have demonstrated that metabolic alterations occur during retinal damage;however to date no study has identified a link between metabolites and retinal regeneration of zebrafish.Here, we performed an unbiased metabolome sequencing in the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid-damaged retinas of zebrafish to demonstrate the metabolomic mechanism of retinal regeneration.Among the differentially-expressed metabolites, we found a significant decrease in p-aminobenzoic acid in the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid-damaged retinas of zebrafish.Then, we investigated the role of p-aminobenzoic acid in retinal regeneration in adult zebrafish.Importantly, p-aminobenzoic acid activated Achaetescute complex-like 1a expression, thereby promoting Müller glia reprogramming and division, as well as Müller glia-derived progenitor cell proliferation.Finally,we eliminated folic acid and inflammation as downstream effectors of PABA and demonstrated that PABA had little effect on Müller glia distribution.Taken together, these findings show that PABA contributes to retinal regeneration through activation of Achaetescute complex-like 1a expression in the N-methyl-Daspartic acid-damaged retinas of zebrafish.

Key Words: Achaetescute complex-like 1a (Ascl1a); metabolomics; Müller glia; p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA); retina; regeneration; zebrafish

Introduction

While adult mammals are not capable of retinal regeneration, and therefore cannot repair the damage caused by retinal degenerative diseases such as glaucoma and retinitis pigmentosa (Goldman, 2014; Hoang et al., 2020;Song et al., 2023), zebrafish are able to completely replace damaged retinal neurons following injury (Lahne et al., 2020).Following retinal injury,zebrafish Müller glia initiate a process of reprogramming and undergo dramatic changes in gene expression that promote regeneration (Lahne et al., 2020).During this process, Müller glia dedifferentiate and proliferate,forming clusters of multipotent retinal progenitors (Müller glia-derived progenitor cells [MGPCs]; Nagashima et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2021).These MGPCs migrate to various retinal layers and further differentiate into all types of retinal cells, thereby restoring vision (Lenkowski and Raymond,2014).In contrast to zebrafish, mammalian Müller glia cannot re-enter the cell cycle and regenerate after retinal injury.However, understanding the retinal regenerative mechanism in zebrafish could provide insight into how to regenerate the mammalian retina by modulating key factors (Hoang et al., 2020), thus potentially improving therapeutic strategies for degenerative diseases of the retina.

Müller glia reprogramming involves multiple molecular mechanisms and requires a complicated and precise regulatory network in zebrafish.Müller glia dedifferentiation and proliferation are regulated by the Achaetescute complex-like 1a (Ascl1a)/LIN28/Let-7 axis (Ramachandran et al., 2010), the Notch signaling pathway (Sahu et al., 2021; Campbell et al., 2022), the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Ramachandran et al., 2011), the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (Zhao et al., 2014), and the transforming growth factor-β(TGF-β) signaling pathway (Sharma et al., 2020), as well as pluripotent transcriptional factors like PAX6 (Thummel et al., 2010), MYC (Mitra et al.,2019), SOX2 (Gorsuch et al.2017), and OCT4 (Sharma et al., 2019).Epigenetic modifications including DNA methylation and histone acetylation also play an important role in retinal regeneration.However, there are still many issues that have not been resolved.A clearer understanding of the endogenous and exogenous initiating mechanisms of Müller glia reprogramming is needed.

Metabolomics is a promising approach for discovering biomarkers.It has been used to study the metabolic basis of many retinal diseases, including agerelated macular degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and retinopathy of prematurity.By providing qualitative and quantitative information regarding low-molecular weight metabolites, this advanced technology can reveal the physiological or pathological state of the retina at specific time points (Li et al., 2021).However, few studies have investigated the role of metabolites in retinal regeneration.The changed metabolites after retinal damage may serve as initiating factors for retinal regeneration.

In this study, we performed untargeted metabolomic analyses and related investigations to detect alterations in metabolites in N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA)-damaged retinas.Particularly, p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA)was detected to decrease significantly, which arouse our interest.PABA is a small organic molecule with many biological applications.Medicinally, PABA is mostly used in sunscreen to protect against UV exposure-related skin disorders.However, the role of PABA in retinal regeneration remains unclear.Importantly, the role of PABA in regulating Müller glia reprogramming and MGPC proliferation, and the specific signaling pathways associated with PABAinduced retinal regeneration in adult zebrafish were further investigated in this study.

Methods

Zebrafish

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were maintained according to standard procedures at the Hunan Key Laboratory of Ophthalmology in Changsha, Hunan, China.AB wild-type fish were used as a wild-type strain.The transgenic zebrafish lines Tg(mpeg1:EGFP)ihb20Tg/+, purchased from the China Zebrafish Resource Center(CZ98, Wuhan, China), were used to monitor microglia behavior.Fish were maintained on a 14-hour/10-hour light/dark cycle under standard conditions.All fish used in these experiments were 6–12 months of age and 2–3 cm in length, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval No.2023030251).Zebrafish were anesthetized by adding 0.02% tricaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis, MO, USA) to the tank water for tissue preparation.

Retinal injury

Zebrafish were anesthetized by adding 0.02% tricaine to the tank water.Next,retinal damage was induced by intravitreal injection of 1 µL of 50 mM NMDA(Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) under microscopic visualization.The NMDA was injected at the corneoscleral limbus using a microinjector (Eppendorf, Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA).

Drug treatments

PABA (Selleck, Houston, TX, USA) and folic acid (FA; Sigma-Aldrich) were used as drug treatments in this study.For PABA treatment, fish were immersed in 3 or 15 µM of PABA in the tank water for 6 hours before retinal damage was induced.After retinal damage was induced, PABA treatment continued until 2 or 4 days post injury (dpi).Control fish were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide(DMSO) at the same concentration as PABA.Fresh PABA or DMSO was added to the water daily.The fish were randomly divided into four groups: the control group, PABA group, NMDA + DSMO group and NMDA + PABA group.

FA was dissolved in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Sigma-Aldrich).Fish were immersed in 10, 100, and 500 µM of FA in the tank water for 6 hours before retinal damage was induced.Controls were treated with NaOH at the same concentration as that used to dissolve the FA.The fish were randomly divided into three groups: the control group, NMDA + NaOH group, and NMDA + FA group,.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from retinas using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen,Waltham, MA, USA), and cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using a Hifair III 1stStrand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai,China).Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRTPCR) (Low Rox, Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was performed as described previously (Mu et al., 2017).The qRT-PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds.The primers used are listed in Table 1.Relative mRNA levels were normalized to those of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and were calculated using the 2–∆∆CTmethod.

Table 1 |Primers used for quantitative quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay analysis

The levels of FA in the retinal supernatants were detected using FA enzymelinked immunosorbent assay analysis (ELISA) kits (EU0381, FineTest, Wuhan,Hubei Province, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence

Fish eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldeyhyde (PFA) for 2 hours at room temperature.After fixation, the eyes were incubated sequentially in 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose solutions (diluted in PBS), then frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T.compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA).The embedded samples were sectioned at a thickness of 16 µm using a CM1860 cryostat (Leica, Wetzler, Germany), and the cryosections were dried on glass slides.

Then, immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously(Ramachandran et al., 2010).Briefly, cryosections were blocked with blocking solution (5% BSA in PBST) for 30 minutes.Next, the cryosections were incubated with the following primary antibodies diluted in the blocking solution overnight at 4°C: rabbit monoclonal anti-GFP (green fluorescent protein, 1:200, Molecular Probes, Cat# A-11122, RRID: AB_221569); rat anti-BrdU (5-bromodeoxyuridine, 1:250, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab6326, RRID:AB_305426); rabbit anti-HuC/D (1:100, Abcam, ab210554); and mouse anti-GS(anti-glutamine synthetase, 1:500, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA, MAB302,RRID: AB_2110656).Following incubation with the primary antibodies, the cryosections were incubated with the secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000, Abcam, ab150077, RRID: AB_2630356), Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rat IgG (1:1000, Abcam, ab150160, RRID: AB_2756445),and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000, Abcam, ab150113, RRID:AB_2576208) for 90 minutes at room temperature.

For BrdU staining, at the indicated time, 20 µL of 20 mM BrdU (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was injected intraperitoneally (IP) into the fish,and 3 hours later they were sacrificed.After preparing the cryosections of eye as above, the cryosections were first immersed in 2 N HCl at 37°C for 30 minutes, then treated with 0.1 M sodium borate (pH 8.5) for 10 minutes and PBS for 10 minutes before standard immunostaining procedures were applied.4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich) was used for nuclear staining.Fluorescence images were captured with a fluorescence microscope(Leica), and BrdU+cells were counted by investigators blinded to the group assignments.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling assay

AnIn SituCell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) was used to detect cell apoptosis in the retina.Briefly,cryosections were fixed in 4% PFA for 5 minutes, washed with PBS, then incubated for 30 minutes in a 1:150 dilution of 10 mg/mL proteinase K in PBS.Slides were then washed with PBS before terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) protocol was performed, as described previously (Zhang et al., 2020).Fluorescence images of retinal sections were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Leica).

Morpholino oligonucleotide-mediated gene knockdown

Lissamine-tagged morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) (0.5 µL, 0.1–0.5 mM)were injected at the same time as NMDA.Intracellular delivery of MOs was facilitated by electroporation (ECM 830 Electro Square Porator, BTX, San Diego, CA, USA), as described previously (Fausett, Gumerson et al.2008).The control and Ascl1a-targeting MOs sequence were described previously(Fausettet al., 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2010), and their sequences were as follows: control morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) 5′-CCT CTT ACC TCA GTT ACA ATT TAT A-3′; Ascl1a MO, 5′-ATC TTG GCG GTG ATG TCC ATT TCG C-3′;Ascl1a5′UTRMO, 5′-AAG GAG TGA GTC AAA GCA CTA AAG T-3′.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy (LC-MS) analysis

At 2 days after NMDA-induced injury, we collected retinas from the NMDA and control groups.Eighty percent methanol was added to the retinas, which were then homogenized by ultrasonication at 60 Hz for 2 minutes, placed in an ice-water bath for 10 minutes, and stored at –20°C for 30 minutes.The extract was then centrifuged at 4°C (12,000 ×g) for 10 minutes.The supernatants from each tube were collected, and the above steps were repeated once.Metabolites were analyzed using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RS UHPLC fitted with a Q-Exactive plus quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with heated electrospray ionization (ESI) source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in both ESI-positive and ESI-negative ion modes.

Untargeted metabolomics analyses

The original liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy data were subjected to baseline filtering, peak identification, integral, peak alignment, and normalization using Progenesis QI V2.3 software (Nonlinear, Dynamics,Newcastle, UK).Compound identification was based on precise mass-tocharge ratio (M/z) and isotopic distribution using The Human Metabolome Database (HMDB, http://hmdb.ca), EMDB (http://ebi.ac.uk/emdb/), and PMDB (https://bioinformatics.cineca.it/PMDB/).

Principle component analysis (PCA) was performed using a data matrix containing both the positive and negative ion data.Orthogonal partial leastsquares-discriminant analysis and partial least-squares-discriminant analysis were used to identify the differential expressed metabolites.Two-tailed student’st-test was used to verify whether there were significant differences in metabolite concentrations between groups.

Molecular docking studies

The X-ray crystal structure of a histone deacetylase (HDAC) with good resolution (0.205 nm) was obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics protein data bank.The ligand properties of trichostatin A (TSA) and PABA were retrieved from the PubChem compound database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).The HDAC binding site (XYZ:65.913, 30.249,1.149) was identified to calculate binding energy.

The binding mode of the ligands to the human HDAC was assessed using the CDOCKER module incorporated into Discovery Studio 3.5 (BIOVIA, Waltham,MA, USA).Protein-ligand complexes with different conformations were obtained, and their specific CDOCKER energies and CDOCKER interaction scores were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Multi-group comparisons were performed by one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’spost hoctest.Inter-group comparisons were performed by two-tailed Student’st-test using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com).All data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean from at least three independent experiments.P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Metabolome sequencing reveals differentially expressed metabolites in NMDA-injected zebrafish retinas; specifically, PABA decreases following NMDA injury and has no effect on retinal cell death

We performed untargeted metabolomic analyses to investigate alterations in metabolites in NMDA-damaged zebrafish retinas.Two days after NMDAinduced injury, we collected retinas and performed metabolome sequencing.The most significantly differentially expressed metabolites (increased and decreased) are listed in Table 2 and shown in the heatmap in Figure 1A.Compared with that in uninjured retinas, there was a significant decrease in PABA (P< 0.05; Figure 1B) in retinas following NMDA-induced injury.

To investigate whether PABA affects retinal cell death in zebrafish, we maintained zebrafish in water containing either DMSO or PABA and conducted TUNEL to quantify retinal cell death.At 1 day post-NMDA injury, no significant difference in the rate of cell death was detected between the PABA and control groups (P> 0.05; Figure 1C and D).NMDA-induced cell death in both groups was primarily localized to the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and inner nuclear layer (INL).These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that significant cell death occurred in the GCL and INL following NMDA injury, owing to the fact that NMDA receptors are mainly expressed by retinal ganglion cells and a subset of amacrine cells (Shen et al., 2006).

Figure 1 |PABA has no effect on retinal cell death.

PABA promotes Müller glia dedifferentiation and division

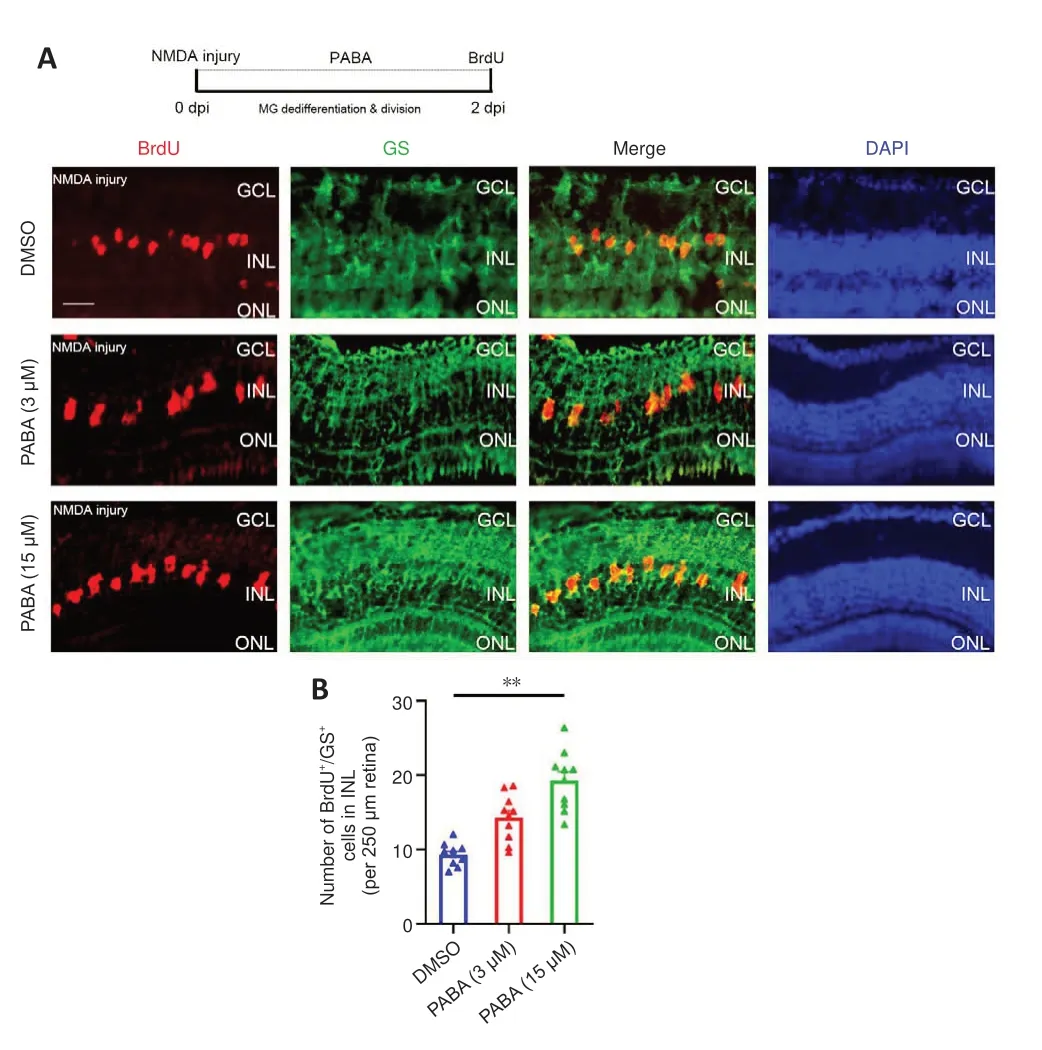

To investigate the effect of PABA on retinal regeneration, we first asked whether PABA contributes to Müller glia reprogramming.The initial steps involved in retinal regeneration in zebrafish include Müller glia dedifferentiation and asymmetric division to generate an MGPC (0–2 dpi),followed by rapid proliferation of MGPCs (2–7 dpi) (Fausettet al., 2008).We performed double immunofluorescence staining for BrdU and glutamine synthetase (GS) to identify proliferating Müller glia in the INL at 2 dpi and MGPCs in the INL at 4 dpi.In retinas treated with DMSO, few BrdU+/GS+Müller glia were observed at 2 dpi (Figure 2A).In contrast, PABA (3 µM)treatment significantly increased the number of BrdU+/GS+Müller glia, in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B), indicating that PABA promotes Müller glia proliferation.In subsequent experiments, we used 15 µM PABA.We did not observe retinal regeneration in an optic nerve crush model (Additional Figure 1), which is consistent with the results reported by Chen et al.(2022).They found no BrdU+cells in the GCL of ONT+retinae at 7 dpi, indicating that retinal ganglion cells had not yet regenerated.

Figure 2 |PABA promotes Müller glia dedifferentiation and division.

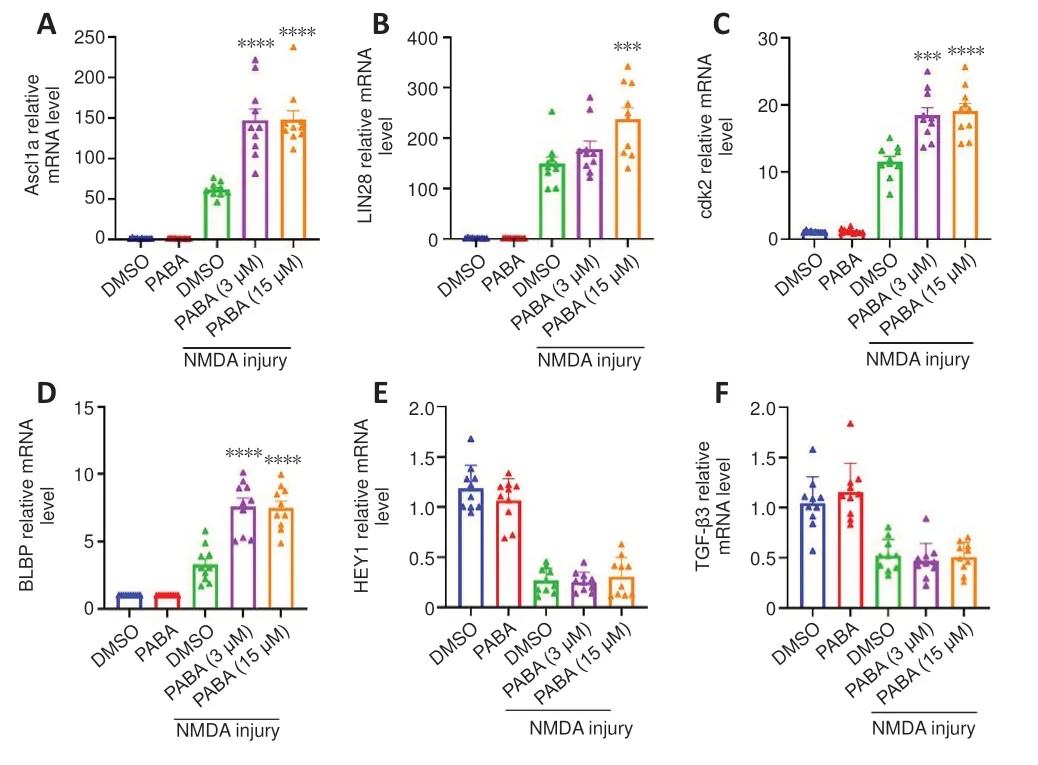

To investigate the mechanism by which PABA promotes Müller glia reprogramming, we carried out qRT-PCR to detect the mRNA expression levels of genes associated with retinal regeneration at 2 dpi.Our results showed that all tested doses of PABA significantly promoted the expression of the key retinal regeneration-associated genes (RAGs) Ascl1a and LIN28 (Figure 3A and B).Additionally, PABA significantly promoted the expression of the cell cyclerelated gene cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (cdk2) and the proliferation-related gene BLBP (Figure 3C and D).However, expression of Hey1 and TGF-β3 were not changed by PABA (Figure 3E and F).Finally, we asked whether PABA alone,without NMDA injury, regulated the expression of these important genes.qRT-PCR analysis showed that their expression levels in PABA-treated zebrafish were comparable to those in control zebrafish (Figure 3A–F), suggesting that PABA alone had no significant effect on retinal regeneration.

PABA promotes MGPC proliferation

To study whether PABA plays a role in MGPC proliferation period, we examined BrdU+/GS+cells in the INL at 4 dpi in zebrafish treated with PABA and DMSO.We maintained zebrafish in PABA and DMSO for 4 continuous days and detected MGPC proliferation in the INL at 4 dpi.The results showed that PABA treatment significantly increased the number of INL BrdU+/GS+cells at 4 dpi compared with the DMSO group (Figure 4A and B), indicating that PABA promoted MGPC proliferation.qRT-PCR analysis showed that PABA treatment for 4 days had no effect on the expression of Ascl1a, cdk2, and BLBP compared with the control (Figure 4C–E).

Table 2 |The most significant differential metabolites

Folic acid has no effect on Müller glia proliferation

PABA is the precursor in FA biosynthesis, and FA is required to make DNA and RNA.We next asked whether PABA promotes retinal regeneration by increasing FA synthesis.First, we examined the FA concentration in retinas 1 and 4 days following NMDA injury.The results showed that there was no significant change in FA levels in the retinas after NMDA treatment (Figure 5A).To study the function of FA in retinal regeneration, we induced NMDA injury in zebrafish, treated the zebrafish with NaOH or FA, and performed BrdU immunofluorescence assay at 2 dpi.Our results showed that the FA group had a similar amount of BrdU+/GS+cells as the control group, regardless of dose, at 2 dpi (Figure 5B and C), indicating that FA does not promote retinal regeneration.As for the mRNA expression levels of RAGs, FA administration had no effect on Ascl1a or cdk2 expression at 2 dpi (Figure 5D and E), in accordance with the BrdU immunofluorescence results.Taken together, these results indicate that FA does not promote regeneration of NMDA-damaged retinas and that PABA does not promote retinal regeneration by increasing FA synthesis.

PABA has no effect on microglial activation

Figure 3 |PABA regulates the mRNA expression levels of key genes associated with regeneration and the cell cycle.

Figure 4 |PABA promotes MGPC proliferation.

Because PABA plays an important role in retinal regeneration that does not involve increasing FA synthesis, we next sought to identify its key downstream signaling pathway.One study showed that innate immunity can regulate regeneration following zebrafish neuronal damage (Mitchell et al.,2018).In addition, more recent studies have shown that activated microglia,a key component of the innate immune system in the CNS, directly affect Müller glia and induce the expression of pro-regenerative inflammatory cytokines in the damaged retina (Conedera et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2020).Thus, to investigate the role of PABA in inflammation following retinal damage, we examined the numbers and morphology of microglia at 2 dpi in the Tg(mpeg1:EGFP) zebrafish line, of which the microglia specifically express GFP.

Figure 5 |Folic acid has no effect on Müller glia proliferation.

In the quiescent zebrafish retina, resting microglia are characterized by their long, irregular processes and fusiform morphology (Nagashima and Hitchcock,2021).After NMDA-induced retinal injury in zebrafish, microglia migrate to sites of cell death, and their morphology changes rapidly and significantly from fusiform to amoeboid.Fluorescence microscopy showed that GFP+cells accumulated in the inner plexiform layer (IPL) at 2 dpi (Figure 6A).The morphology of most of the GFP+cells at the injury sites was amoeboid,suggesting that they were activated microglia.In contrast, the GFP+cells in the uninjured group exhibited ramified morphology and were present in multiple different layers of the retina.There was no significant difference in the number of GFP+cells between the PABA group and control, indicating that PABA did not promote microglial activation (Figure 6B).

PABA does not alter MGPC distribution during MGPC differentiation

A previous study showed that MGPCs are intrinsically multipotent, migrate to any damaged nuclear layer, and differentiate into the appropriate cell type for that specific layer, although there is a proliferative bias in the most severely damaged nuclear layers (Powell et al., 2016).To assess the impact of continuous PABA treatment on MGPC distribution and retinal regeneration,we treated zebrafish with PABA for 21 days.Immunofluorescence showed that PABA treatment increased the number of BrdU+cells at 21 dpi compared with the control (Figure 7A and B), suggesting that MGPC increased in response to PABA treatment.Compared with the control, PABA treatment did not significantly alter the percentage of BrdU+cells in different retinal layers (Figure 7C), suggesting that PABA administration did not affect MGPC multipotency or distribution.In addition, staining for regenerated neurons, which were represented by BrdU+cells expressing major cell-type markers INL HuC/D(amacrine cells) or GCL HuC/D (retinal ganglion cells) showed that there was no difference in the percentage of regenerated neurons between the PABA group and the control group (Figure 7E).In conclusion, PABA promoted MGPC proliferation but had no effect on MGPC distribution.

Figure 6 |PABA has no effect on microglial activation.

Figure 7 |PABA does not change MGPC distribution during differentiation.

PABA promotes retinal regeneration in an Ascl1a-dependent manner

Our data suggest that PABA promotes retinal regeneration and increases Ascl1a expression.Because Ascl1a was previously shown to be a key factor in Müller glia dedifferentiation and MGPC proliferation (Ramachandran et al.,2010), we asked whether its induction in PABA-treated retinas was necessary for retinal regeneration.To test this, we performed gene knockdown of Ascl1a by intravitreally injecting a control or Ascl1a-targeting MO into PABA-treated zebrafish and labeled the proliferating Müller glia with BrdU at 2 or 4 dpi.The results showed that the Ascl1a-targeting MO significantly reduced the number of Müller glia by 80% in the PABA-treated retinas compared with the control MO at 2 dpi (Figure 8A and B).Furthermore, compared with the control MO,Ascl1a knockdown caused a significant reduction in MGPC proliferation, by 80%, at 4 dpi (Figure 8C and D).These findings are consistent with a previous study reporting that Ascl1a knockdown suppressed Müller glia division and MGPC proliferation in the injured retina (Ramachandran et al., 2010).These results indicate that PABA promotes retinal regeneration by increasing Ascl1a expression.

Figure 8 |PABA promotes retinal regeneration in an Ascl1-dependent manner.

Docking analysis of the interaction between HDAC and PABA

Regarding the mechanism by which PABA affects Ascl1a expression, we hypothesized that histone acetylation acts as a mediator.A previous study has proved that several benzoic acid derivatives inhibit HDAC by binding to its trichostatin A (TSA)-binding site.Ascl1a overexpression, as well as the HDAC inhibitor TSA, have been shown to promote Müller glia reprogramming and produce functional interneurons in mice.We therefore predicted that PABA,a kind of the benzoic acid derivatives, can interact with HDAC and assessed their binding efficacy at the HDAC TSA-binding site.Interestingly, PABA showed a stronger interaction with HDAC, with lower C-docker energy (–48.47 kcal/mol), than TSA (–19.04 kcal/mol).Similarly, the C-docker interaction of PABA with HDAC (–49.26 kcal/mol) was relatively higher than that of TSA with HDAC (–51.53 kcal/mol) (Additional Figure 2).Taken together, the docking study findings show that there is a potent interaction between PABA and HDAC.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the role of PABA in retinal regeneration in adult zebrafish.The results showed that PABA expression levels were decreased in NMDA-damaged retinas, and that PABA was required for Müller glia reprogramming and division, as well as MGPC proliferation.As for the mechanism by which it promotes regeneration, PABA had no effect on microglial activation.The possibility that PABA promotes FA synthesis was excluded, as FA had no effect on retinal regeneration.Importantly,PABA promoted retinal regeneration by activating Ascl1a, which is a key transcription factor in Müller glia reprogramming.Finally, PABA administration did not alter MGPC multipotency or the distribution of regenerated neurons throughout the retinal layers.

Visual loss and blindness caused by retinal disease has a significant negative effect on the quality of life of many people.Metabolomics, a promising tool for discovering various biomarkers, has been applied in many retinal diseases.Several metabolites including cyclic AMP and 2-methylbenzoic acid have been demonstrated to be associated with glaucoma (Tang et al., 2021).The key molecules and mechanism of retinal regeneration may be hidden among these metabolites.We performed metabolomics analysis of adult zebrafish subjected to NMDA-induced retinal damage.A large number of differentially expressed metabolites were detected in NMDA-damaged retinas at 2 dpi,which implies that metabolites participate in retinal regeneration.Most of the metabolites whose expression was increased after NMDA-induced injury belonged to the superclass of lipids and lipid-like molecules.A previous study showed that inhibiting cholesterol synthesis promotes axonal regeneration in the injured central nervous system, including the optic nerve (Shabanzadeh et al., 2021).The function of these lipids in retinal injury and regeneration deserves further investigation.In contrast, some metabolites (e.g., pyridines and carboxylic acids) exhibited reduced expression in response to retinal injury.The consumption of these metabolites during regeneration-associated synthesis may account for their reduced levels at 2 dpi after NMDA-induced injury.In particular, PABA levels were decreased following NMDA-induced injury.

This is the first demonstration that the metabolite PABA plays a role in retinal regeneration.It has been demonstrated in several studies that PAPA promotes cell proliferation.PABA stimulates the proliferation of corneal stroma keratoblasts in the adult rat cornea (Sologub et al., 1994).In addition, the PABA derivative 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide increases cell proliferation and improves neurogenesis after ischemic stroke by inhibiting myeloperoxidase activity (Kim et al., 2016).In response to retinal injury, zebrafish exhibit two processes: Müller glia dedifferentiation and division, and rapid proliferation of MGPCs.Our results suggested that PABA plays a positive role in MGPC generation and proliferation after retinal damage induced by NMDA in zebrafish.More detailed analysis indicated that PABA promotes Müller glia dedifferentiation and division, as well as MGPC proliferation.

Signaling transduction pathways related to Müller glia reprogramming have been identified in numerous studies.Among them, the Ascl1a/LIN28/Let-7 axis is considered to be the key signaling pathway regulating Müller glia reprogramming (Ramachandran et al., 2010).Ascl1a, a proneural basic helixloop-helix transcription factor, contributes to Müller glia reprogramming following retinal injury in zebrafish.Ascl1a expression is rapidly upregulated within 4 hours post-injury and reaches peak levels at 4 dpi.Ascl1a, which is located at the center of the regeneration regulatory network, regulates many RAGs, including STAT3 (Nelson et al., 2012), Wnt signaling (Ramachandran et al., 2011), Notch signaling, Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling (Kaur et al., 2018),MYC (Mitra et al., 2019), OCT4 (Sharma et al., 2019), and RNA-binding protein LIN28 (Ramachandran et al., 2010).In particular, Ascl1a can directly bind to LIN28 promoter to activate its expression.LIN28 suppresses the microRNA Let-7, thereby de-inhibiting the expression of multiple pluripotency genes,including Ascl1a and LIN28.Our study demonstrated that PABA up-regulated Ascl1a and LIN28 expression to promote Müller glia regeneration, while the Notch and TGF-β pathways were not influenced by PABA.Furthermore, Ascl1a knockdown reduced Müller glia numbers by 80% in PABA-treated retinas at 2 and 4 dpi, which suggests that Ascl1a is necessary for retinal regeneration in PABA-treated retinas.A previous study showed Ascl1a knockdown almost completely suppressed MG proliferation in the injured retina; this apparent discrepancy may be because of differences in transfection efficiency.BLBP expression is a marker of radial glial cells and is associated with radial glial cell proliferation in the brain (März et al., 2010; Diotel et al., 2016).The current study is the first to report increased BLBP expression in zebrafish retinas following NMDA-induced damage.

PABA is a precursor of folic acid (FA) (Krátký et al., 2019), an important B vitamin that, when used as a supplement by pregnant individuals, reduces the incidence of neural tube defects by 50–70% (Carter et al., 1999; Crider et al., 2022).Protein and nucleotide synthesis, as well as molecule methylation,require the participation of one-carbon units, and FA is an indispensable cofactor for transferring one-carbon units.Therefore, FA is mainly involved in thede novosynthesis of purines and pyrimidines and is required for DNA and RNA synthesis (Goossens et al., 2021).However, the results that FA administration had no effects on MGPC proliferation excluded the possibility that PABA exerted functions through FA pathway.

Recent evidence suggests that inflammation plays an important role in retinal regeneration.One study showed that microglia/macrophage-mediated inflammation promotes retina regeneration through upstream regulation of the mTOR signaling pathway (Zhang et al., 2020).Thus, chemical compounds that induce retinal inflammation may promote retinal regeneration.Zymosan,a yeast cell wall derivative, induces acute intraocular inflammation, leading to accelerate axonal regrowth and promoting retina regeneration after optic nerve injury (Kyritsis et al., 2012), while PABA had no effect on the retinal inflammation in this study.

Regardless of which nuclear layer was damaged, Müller glia respond by generating multipotent progenitors that migrate to all nuclear layers and differentiate into layer-specific cell types, suggesting that Müller glia in the injured retina are intrinsically multipotent (Powell et al., 2016).At 21 dpi,MGPCs have migrated to their final positions and reside in specific nuclear layers as differentiated cells.In this study, we focused on the effect of PABA on MGPCs at 21 dpi.Our results indicated that PABA promoted MGPC proliferation but had no effect on MGPC distribution.

We found that PABA levels decreased following NMDA-induced injury,presumably because PABA was consumed during the process of retinal regeneration.Adding supplemental PABA to injured retinas resulted in enhanced Müller glia reprogramming through the Ascl1a pathway.As for the mechanism by which PABA affects Ascl1a, we first considered epigenetic modification.The role of histone acetylation, an essential epigenetic change, in Müller glia reprogramming has been studied.Histone acetylation is also an important factor regulating developmental neurogenesis and CNS regeneration (Palmisano et al., 2019; Gomez-Sanchez et al., 2022).In addition, histone deacetylase 1 (HADC1) is quickly downregulated after injury to de-repress RAGs, including Ascl1a, LIN28, and MYC (Mitra et al., 2018).In mice, Ascl1a overexpression or treatment with the well-known HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) promotes Müller glia reprogramming and produces functional interneurons (Jorstad et al., 2017).We therefore hypothesized that PABA interacts with HDAC, and assessed PABA binding efficacy at the HDAC TSA-binding site.The results showed that PABA interacted more strongly with HDAC than with TSA.

In this study we showed that the metabolite PABA promotes retinal regeneration after NMDA-induced damage by upregulating Ascl1a in adult zebrafish.In particular, it promotes Müller glia reprogramming and division, as well as MGPC proliferation.The primary goal of studying retinal regeneration in zebrafish is to gain insight into potential approaches to treat or cure neurodegenerative diseases of the human retina and brain.The results from our study may help develop treatments based on metabolites to promote human retinal regeneration in the future.The precise mechanism by which PABA promotes Ascl1a activation during retinal regeneration requires further investigation.To address this, injured retinas treated with PABA could be subjected to RNA sequencing analysis to identify candidate pathways in Müller glia involved in retinal regeneration.Further approaches such as gene editing and molecular interaction studies are needed to identify the core molecules that are responsible for PABA binding and retinal regeneration.Finally, while metabolites have primarily been investigated for their role in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders, less is known about their function in retinal regeneration, which merits further attention.

Author contributions:All authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design,or acquisition of data,or analysis and interpretation of data;and all have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content;and all have given final approval of the version to be published;All agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability statement:All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Additional files.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal,and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License,which allows others to remix,tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially,as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Additional files:

Additional Figure 1:No retinal regeneration was detected in a zebrafish model of optic nerve crush.

Additional Figure 2:Additional Figure 2 The interaction between p-aminobenzoic acid(PABA)and human histone deacetylase(HDAC).

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- The big data challenge – and how polypharmacology supports the translation from pre-clinical research into clinical use against neurodegenerative diseases and beyond

- Lupenone improves motor dysfunction in spinal cord injury mice through inhibiting the inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in microglia via the nuclear factor kappa B pathway

- Two-photon live imaging of direct glia-to-neuron conversion in the mouse cortex

- Ferroptosis mechanism and Alzheimer’s disease

- Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate neuroimmunothrombosis

- Impact of increasing one-carbon metabolites on traumatic brain injury outcome using pre-clinical models