建筑的绝对可持续性视角

2024-01-27安妮贝姆英格博格

安妮·贝姆,英格博格·豪

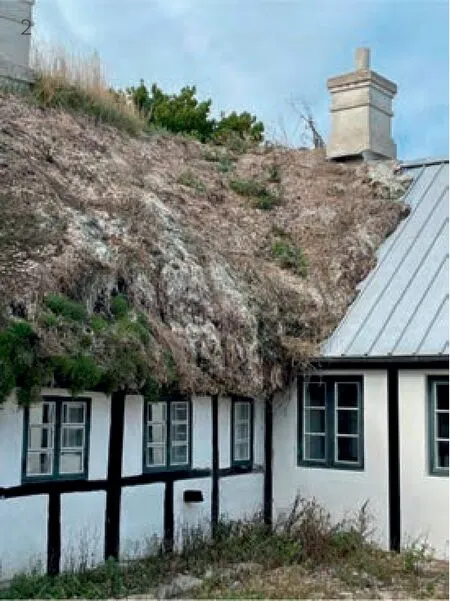

前文《何谓绝对可持续性》介绍了我们在思考建造可持续性时对其含义产生的新理解。在本文中,我们将讨论相关策略对未来的建筑环境和我们的生活条件可能有哪些影响(图1)。

1 再利用木围护的细部 Detail of reused wood cladding

新的可持续实践将如何影响我们思考、设计和建造建筑的方式?基于地球边界的概念,绝对可持续性的审美和感官体验将是怎样的?在建筑世界中,绝对可持续性看上去、闻起来和给人的感受将是怎样的?

1 普遍问题下的普适风格

如果我们回顾过去70 年,建筑材料的使用在建筑历史中不过是一个小小的插曲。在20 世纪之前,材料不仅选择极为有限,而且往往只经过极低程度的加工,建造方法也比今天简单得多。然而,当我们回顾过去70 年的影响,以及高度技术化和能源密集型的建筑方法对我们的生活标准、全球发展以及地球的影响(现在状况不佳)时,其重要性不言而喻[1]。

讨论建筑的绝对可持续性策略时,需要着重思考“新”的资源密集型建造方法和我们当代的建筑文化[2]。为了最终消除碳排放、废物和建筑行业的污染效应,事情应当向好的方向转变。

二战后,工业化国家的现代建筑意味着扩大化的中产阶级的生活水平有所提高。中等收入家庭得以从市中心卫生条件不佳的公寓搬出,那里有太多人住在拥挤的低标准建筑里[3]。取而代之的是,他们搬到了郊区新建的标准住宅区或独栋平房中,那里有室内管道、新鲜空气、日光和充足的绿化[4]。

The previous article "What is absolute sustainability" introduces a new understanding of what we mean when we consider something built to be sustainable.In this article,we'll discuss what these strategies might mean for the future built environment and our living conditions (Fig.1).

How will new sustainable practices impact the way we think,design,and build architecture?What are the aesthetics and sensory experiences associated with absolute sustainability based on planetary boundaries? And how will absolute sustainability look,smell and feel in the world of architecture?

1 A Universal Style with Universal Problems

If we look back over the past 70 years,the use of materials for buildings is not much more than a minor parenthesis in the long history of architecture.Before the 20th century,the selection of materials was limited and often only minimally processed,and the construction methods were simpler than what we see today.However,when we look at the impact on our living standards,global development,and the (now poor) condition of our planet,the impact of these past 70 years and their highly technological and energy-intensive building methods cannot be overstated[1].

When discussing strategies for absolute sustainability in architecture,"novel" resource-intensive construction methods and our contemporary building culture need to be addressed[2].Ultimately,things need to change for the better to eliminate the negative consequences of carbon emissions,waste,and pollutive effects in the construction sector.

Modern architecture in industrialised countries in the period after WWII meant a rise in living standards for an expanding middle class.Families with middle incomes became able to move out of the unsanitary apartments in city centres,where too many people were living in overcrowded lowstandard buildings[3].

Instead,they moved into newly constructed uniform building blocks or bungalows in the suburbs,where they had access to indoor plumbing,fresh air,daylight and green surroundings[4].

Furthermore,due to mass production,new infrastructure,and the innovative use of materials such as reinforced concrete,steel and composites,development happened fast and at an affordable cost for the masses.In the 1960s and 1970s,new buildings and structures appeared at a considerable rate in the suburbs of large cities in industrialised countries and beyond.

On an even bigger scale,this period also marks the advent of megacities in Southeast Asia,the USA and South America,with the shift to market-driven socialism (e.g.in China) and special economic zones setting economic growth free.Concurrently with this enormous expansion of cities and infrastructure around the world,carbon emissions have also increased substantially[5].

2 From Growth to Reconsideration

Today,the aim is to improve our built environment to make it more sustainable,but to do that we cannot use market economy measures for success,such as growth in wealth or productivity.In order to advance the built environment within the planetary boundaries,we need to carefully consider all the materials,processes and solutions that go into every single structure we intend to build.The most sustainable structure is "the building we don't build," and the most sustainable materials are the materials we do not harvest,process,or use in construction.

Against the backdrop of the oil crisis of the 1970s,a broad understanding finally began to emerge in industrialised countries that they must share our planet's resources with the rest of the world.The planet's resources are everyone's resources.As with energy-intensive societies,all industrialised countries have a responsibility to reduce their carbon footprint and act within the safe operating space of the planetary boundaries.

Consequently,when we design and build today and in the future,we must apply "strategies of avoidance" to reduce our general consumption and exploitation of materials and energy resources.In addition,we must ask ourselves: Do we really need a new building? Can we use an existing one? Can we renovate an older building for new purposes? Can we transform buildings for multi-functional use or long-perspective purposes?

此外,由于大规模生产、新基础设施和对钢筋混凝土、钢铁和复合材料的创新使用,房产开发迅速以可负担的成本适应了大众需求。在1960 年代和1970 年代,工业化国家大城市的郊区迅速出现了许多新建筑。在更大的范围上,这个时期,东南亚、美国和南美的超级城市的出现,意味着市场驱动的社会主义(例如中国)和设立经济特区使经济得以快速增长。然而,与全球城市与基础设施的巨大扩张同时出现的是碳排放大幅增加[5]。

2 从增长到重新审视

当前的目标是改善我们的建成环境,使其更加可持续,但为了做到这一点,我们不能用市场经济衡量成功的标准,比如财富增长或生产力,来看待这一问题。为了在地球边界内推动建筑环境的改善,我们需要仔细考虑每一座计划建造的建筑中涉及的所有材料、工艺和解决方案。最可持续的建筑是“我们不建造的建筑”,最可持续的材料是我们不采集、加工或用于建筑的材料。

在1970 年代的石油危机背景下,工业化国家终于开始形成一个广泛的认识:必须与世界其他地方分享我们地球的资源。地球资源是每个人的资源。作为能源密集型社会,所有工业化国家都有责任减少碳足迹,并在地球边界的安全运营空间内行事。

因此,当今天和未来进行设计和建造时,我们必须采用“避险策略”来减少对材料和能源的普遍消耗和开采。此外,我们必须扪心自问:真的需要一座新建筑吗?能否使用现有的建筑?能否将一座旧建筑改造赋予它新的功能?能否将建筑物改造成多功能用途或长期用途?

当我们进行改造、更新或建造时,应当使用碳足迹较低的材料,例如吸收和储存CO2的生物材料,或者应当重复使用那些通常会遭废弃的材料。在这个意义上,我们必须考虑所使用的材料的方方面面。它们是如何提取、种植或采集的,如何制造、加工、运输的?它们的数量足够吗?可再生吗?它们在保温隔热、室内气候等方面是否符合我们的期望或需求?

尽管我们必须忽略现代建筑业所建立的许多“成功参数”,诸如工业化技术的效率、建筑标准和材料性能等,但仍然需要关注它们所带来的品质优势。例如,获取清洁水、卫生设施、日光和新鲜空气等为代表的生活水平的普遍改善,绝不能被牺牲。人道主义和环境可持续性紧密相连,在建筑的绝对可持续性方面,它们必须被平等考虑。

3 从普适到本地化

实现被认为具有绝对可持续性的建筑解决方案的一个最主要挑战可能是:如何将人文理想与我们“重建”后的对负责任的材料使用的认识结合起来?也许这需要重新审视我们的本地建筑的地域性?

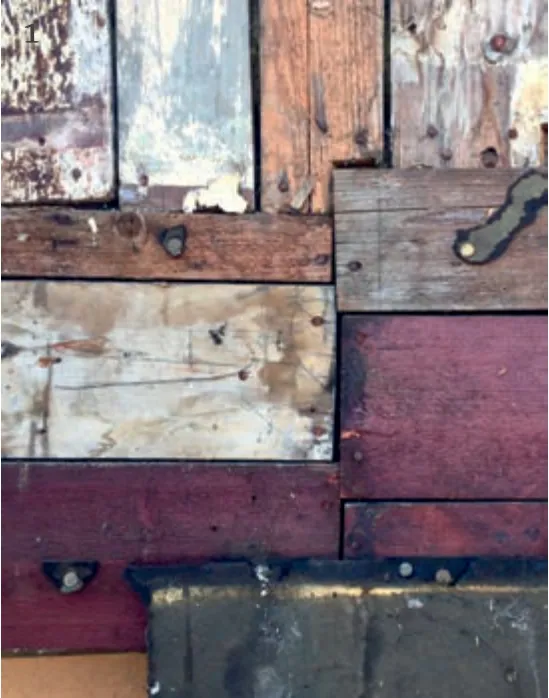

在工业化生产成为主流之前,建筑发展是基于当地知识、工艺和地区建筑传统的,这些传统建筑与工业化建筑相比,经过了数千年的培育、测试和完善。例如,北欧地区使用木材、稻草、海草和石头有着充分的理由。这些材料易于获取,并有效地为人们提供了避寒的居所(图2)。其他例子包括夯土和日晒土,在一些非洲地区,它们唾手可得,传统上被用作建造遮阳庇护所的建筑材料。此外,埃塞俄比亚使用编织的稻草作为建造圆形土库尔小屋的主要材料[6]。

2 古老与创新的技术在丹麦Læsø岛相遇 Old and new technologies meet on the Danish island of Læsø

本地化的建筑实践的演变基于当地人口的基本需求、文化、工艺和资源获取方式。寻求更加可持续的建造方法,我们需要重新唤起对这类策略的认识。然而,这并不意味着抹杀我们迈向更好生活水平的努力。最终,我们需要将这些洞察与对当地资源的获取和与现实背景相关的专业知识结合起来。

材料的稀缺性和谨慎利用现有的材料并非建筑施工历史上的新现象。事实上,只有少数社会在一段时间内忽略了这一点。使用当地可获得、可再生且能够改良或充分利用现有材料一直是最有效和可持续的建筑方法。

4 从灰色到多彩

从美学角度来看,这种更新的策略可能带来更有趣、更具触感和更易于相关者参与的建筑。也许通过清晰可辨的材料构建的建筑甚至可以使我们嗅到、感受到、理解周围的材料和构筑物,重新建立与自然更紧密的联系(图3)。

3 在致力于绝对可持续建筑的建造中,避免过度使用技术,转而使用未经处理或重复使用的材料,它们提供了丰富、随 时间不断变化的颜色和纹理 When building with an aim towards absolute sustainable architecture and to avoid excessive technologies,natural,untreated materials,or reused materials offer a wide range of colours and textures,that keep changing over time

这甚至可能会产生更加丰富多彩、富有冒险精神和动态张力的建筑。木材会随着时间和温度的变化而膨胀、收缩,木结构表面可以追溯到相关信息。生物材料会对其周围环境产生反应并改变颜色。崭新的茅草屋顶是鲜黄色的,而老旧的则变为灰色。新生产的材料可以按照人喜欢的颜色定制生产,而重复使用的材料则呈现出随机的拼贴图案(图4)。如果您选择优雅而怀

4 重复使用的木材充满了来自其过去生活的各种变化和故事 Reused wood is full of varieties and stories from its past life

And when we transform,refurbish or build -we must use materials that have a low carbon footprint,such as biogenic materials that absorb and store CO2,or we must reuse materials that would normally become waste.In this sense,we must consider all aspects of the materials we intend to use.How are they extracted,cultivated or harvested? How are they manufactured? How are they processed? Where are they transported from and how? Is there enough of the materials? Are they renewable? And do they meet our expectations or needs in terms of insulation,indoor climate,etc.?

Although we must disregard many of the "parameters of success" that led to the ideas upon which the modern construction industry was founded,such as the efficiency of the industrialised technology,the building standards,and the material performances,we still need to pay attention to the qualities offered by them.For instance,a general improvement in living standards,in the form of universal access to clean water,sanitation,daylight,and fresh air,must not be sacrificed.Humane and environmental sustainability are deeply intertwined and must be considered on equal terms when it comes to absolute sustainability in architecture.

3 From Universal to Local

One overriding challenge to achieving architectural solutions that can be claimed to offer absolute sustainability might be: how to combine humanistic ideals with our "re-established"knowledge of responsible material use? Perhaps this would require revisiting our local building vernaculars?

Before industrialised production of buildings became dominant,development in construction was based on local knowledge,craftsmanship and regional building traditions,which,in contrast to industrialised construction,have been cultivated,tested and refined over thousands of years.For instance,the Nordic regions use wood,straw,eel grass and stone for good reasons.These materials were easy to get hold of and efficiently sheltered people from the cold,harsh climate (Fig.2).Other examples are rammed and sundried earth,which have traditionally been used in some African regions as the obvious building material for creating shelter from the sun.Then there is braided straw like that used in Ethiopia as the primary material for building round Tukul huts[6].

The evolution of local building practices is based on the local population’s basic needs,culture,craftsmanship and access to resources.As we seek to build more sustainably,we need to reawaken these types of strategies.However,this does not mean erasing our progress towards better living standards.Ultimately,we need to combine these insights with our access to local resources and knowhow linked to the present context.

Material scarcity and careful use of what is to hand is not a new phenomenon in the history of building construction.In fact,it has only been ignored by a few societies,and only for a time.

Building with materials that are locally available,renewable,and that transform or improve what you already have has always been the most efficient and sustainable approach to building.

4 From Grey to Multi-Coloured

Aesthetically,this renewed strategy might bring us architecture that is more interesting,tangible and easier for users to engage with.Architecture made from materials that are clear and recognisable.Perhaps even architecture that re-establishes a closer connection with nature by enabling us to smell,feel,sense and understand the materials and structures that surround us (Fig.3).

It might even lead to more colourful,adventurous,and dynamic architecture.Wood expands and contracts over time depending on the temperature,which can be traced in the surfaces of a wooden structure.Biogenic materials react to their surroundings and change colour.A brand-new thatched roof is bright yellow,while an older one is grey.Newly produced materials can be ordered in exactly the colour you prefer,while reused materials come with a random patchwork (Fig.4).If you transform an existing building elegantly and respectfully,its history will help shape its future use and give it aesthetic character.

There are cultural values linked to biogenic materials,transformations,and local building practices.By using these elements,we might be able to establish a closer link between buildings,有敬意的方式改造现有建筑,它的历史将有助于塑造其未来的用途,赋予其美学特质。

这些都具有与生物材料、转化和当地建筑实践相关的文化价值。通过使用这些元素,我们或许能够在房屋、建筑和人之间建立更紧密的联系。它甚至可能促进使用者与其家园之间的直觉联系,因为它在材料、建造方式和历史等方面都与当地文化相关联。这将激励使用者更好地照顾他们的家园,延长其使用寿命。

5 从完美到灵活

作为建成环境的专业人士和利益相关者,我们所受的教育让我们要去想象完成的项目。像现代主义者一样,我们被自己想要实现的理念所驱使,这些理念指导着我们进行设计和建造。我们设想,然后努力实现“一座完美的建筑,在完美的广场上,美丽的人们在一个阳光明媚的春日里在其周围活动,使用它”。最好的赞美是看到它被建造并完全按照原始草图中描述的方式被使用。然而,这既不是建筑的运作方式,也不是我们能够去理解的它们在生命周期内与使用者的互动方式。

尽管具有长寿命的建筑本身更加可持续,但实际上很难估计哪些建筑将有最长的寿命。通常,最受人喜爱的建筑具有最长的寿命。因为人们对它们有一种主人翁意识,关心它们,并努力让建筑适应自己的使用和需求。生命周期分析(LCA)做得最好的建筑不一定是寿命最长、生命周期影响最大的建筑。

为了在地球边界内运行,我们必须改变看待建筑及其在社会中作用的方式(图5)。我们在设计和建造建筑时,是否应该追求灵活性、适应性、空间品质和美感,而不是追求完美、永恒的标志性?使用当地的、可再生的和可获得的材料是否意味着我们的建筑就需要永恒不变?如何才能澄清我们对理想的响应式建筑的认识,从而使我们只在有充分理由的情况下使用新材料?

5 粘土板可以通过天然染色改变表达 Clay plates can change expression through natural dye

6 灵感取代标准

在创新设计和建造方式时,我们必须敢于重新思考我们的理想和相关规定。我们不能让法规和工业标准的上限或下限来定义建筑的目的,更不能任由它们定义我们的设计、改造和建造方式。当下的建筑法规和标准不应阻挠新的解决方案,尽管法律框架本质上是保守的。它们纯粹无法满足当前和未来对建筑业可持续转型的需求。这一点在审视回收材料的再利用机会时尤为明显,因为回收材料的物质属性必须符合新材料的标准,而这几乎是不可能的。

因此,建筑绝对可持续发展的最重要的切入点或许不是确定其标准和美学,也不是将其建筑实践系统化。相反,我们应该制定战略和共识,帮助建筑业更好地在地球边界内运转,并激发创造新的可持续解决方案。我们需要释放我们的创造力,重新发现传统的建筑技术,重新考虑我们的材料资源,以全新的方式建造与今天截然不同的建筑(图6、7)。建成案例具有强大的影响力,相关法规需要为截然不同的实践留出空间,这不需要成本高昂的额外的编制工作,我们想要摆脱那些构成了现行标准和法规基础的先例。□(本文的主要内容与《无为创新——引领建筑环境可持续变革所需的能力》[7]一书有着密切联系。)architecture and people.It may even promote an intuitive attachment between a user and their home thanks to the local cultural connection to its materials,building methods and history.And this might inspire the user to take better care of their home and thereby extend its lifetime.

6 不同形状和形式的夯土变化 Variations of rammed clay in different shapes and forms

7 茅草屋顶的特写 Close up of a thatched roof

5 From Perfection to Flexibility

As professionals and stakeholders in the built environment,we are taught to visualise the finished project.Like the Modernists,we are driven by ideas that we want to turn into built reality,and it is these ideals that guide us through the design and building processes.We imagine and then strive to realise "a perfect building in a perfect square with beautiful people who use it and move around on it,on a sunny spring day".And with no better compliment than to see it built and used exactly as depicted in the original sketches.However,this is not how buildings work nor is it how we can understand their interaction with users throughout a lifetime.

While buildings with a long life span are in themselves more sustainable,in reality it is difficult to estimate which buildings will live the longest.Often,it is the buildings that are most loved that have the greatest longevity.Because people feel an ownership towards them,care for them and make an effort to adapt them to their uses and needs.The buildings with the best Life Cycle Analysis (LCA)are not necessarily the ones with the longest life span and the best life cycle impact.

To navigate within the planetary boundaries,we must change the way we look at architecture and its role in society (Fig.5).Instead of striving for perfect,everlasting iconic buildings,should we instead look for flexibility,adaptability,spatial qualities,and beauty when we design and build? Does using materials that are local,renewable and available mean that our buildings then need to last forever? How can we clarify our perceptions of an ideal responsive architecture,so that we only use new materials for good reasons?

6 Inspiration Instead of Standards

When innovating the ways in which we design and build,we must dare to rethink our ideals and our formal regulations.We cannot allow regulations and minimum or maximum industrial standards define the purpose of architecture,and thus how we design,transform and build.Today’s building regulations and standards should not hinder new solutions,since legal framework is by nature conservative.They simply do not respond to current and future demands for the sustainable transformation of the construction industry.This is particularly evident when looking at the opportunities for reusing salvaged materials,which is almost impossible due to the fact that their material properties must match the standards of new materials.

Consequently,the most important perspective on absolute sustainability in architecture is,perhaps,not to define its standards and aesthetics or to systemise its building practices.Instead,we should formulate strategies and understandings that help the construction industry to better navigate within the planetary boundaries and that inspire the creation of new sustainable solutions.We need to set our creativity free,rediscover traditional building techniques,and reconsider our material resources in order to build in new ways that are radically different to what we do today (Fig.6,7).Built examples have a powerful effect,and the regulations need to make room for a completely changed practice,without having to go through costly extra documentation,which is not required by the practices we want to get rid of because they form the foundation for current standards and regulations.□ (The main content of this paper is closely related to the book Innovation of Nothing: The capabilities needed to lead sustainable change in the built environment[7].)