Sexual Dimorphism,Female Reproductive Characteristics and Embryonic Thermosensitivity in the Tonkin Forest Skink (Sphenomorphus tonkinensis)from Hainan,South China

2024-01-02YuDUChixianLINXiamingZHUYuntaoYAOandXiangJI

Yu DU ,Chixian LIN ,Xiaming ZHU,2 ,Yuntao YAO and Xiang JI

1 Hainan Key Laboratory for Herpetological Research,College of Fisheries and Life Sciences,Hainan Tropical Ocean University,Sanya 572022,Hainan,China

2 Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory for Water Environment and Marine Biological Resources Protection,College of Life and Environmental Sciences,Wenzhou University,Wenzhou 325035,Zhejiang,China

Abstract We collected 75 adult Tonkin forest skinks(Sphenomorphus tonkinensis)from Hainan,South China and incubated eggs at four constant temperatures ranging from 22°C to 28°C to study sexual dimorphism,female reproductive characteristics and embryonic thermosensitivity.The largest male was 53.4 mm snout-vent length (SVL),and the largest female was 54.3 mm SVL.The mean SVL was slightly greater in adult females(49.9 mm)than in adult males(48.8 mm),but the difference was not significant.Head length,head width,fore-limb length and hindlimb length were longer in adult males and abdomen length was longer in adult females after accounting for SVL.Accordingly,we conclude that S.tonkinensis is basically a sexually size-monomorphic species with sexual dimorphism in head size,abdomen (trunk)length and limb size.Females laid up to two clutches of 1-4 eggs each per egg-laying season from February to May.Egg mass,clutch size and clutch mass were independent of female SVL.Embryonic stages at laying varied from Dufaure and Hubert’s stage 30 to 31.With female SVL held constant,the negative correlation between egg mass and clutch size was not significant,suggesting that the offspring (egg) sizenumber trade-off between is not evident or eggs are well optimized for size in S. tonkinensis.None of the eggs at 28°C hatched;hatching success was lower at 22°C than at 24°C or 26°C.The mean incubation length was 52.9 d at 22°C,40.4 d at 24°C and 33.6 d at 26°C.Hatchlings from eggs incubated at 22°C,24°C and 26°C did not differ morphologically at hatching,suggesting that temperatures within this range do not differentially affect hatchling morphology in S. tonkinensis.

Keywords egg,hatching success,hatchling morphology,incubation length,reproduction,Scincidae,sexual dimorphism

1.Introduction

Asian forest skinks of the genusSphenomorphusFitzinger,1843(Sauria,Scincidae) are either oviparous or viviparous,occurring in South,Southeast and East Asia and on islands of the West Pacific(Uetzet al.,2021).Of some 115 currently recognizedSphenomorphusspecies,seven (the Medog Forest SkinkS.courcyanus,the Earless Forest SkinkS.cryptotis,the Brown Forest SkinkS.incognitus,the Indian Forest SkinkS.indicus,the Spotted Forest SkinkS.maculatus,the Taiwan Forest SkinkS.taiwanensisand the Tonkin Forest SkinkS.tonkinensis)can be found in China(Huang,1999;Darevskyet al.,2004;Nguyenet al.,2011,2012;Qiet al.,2022),withS.taiwanensisendemic to the country and found only in Taiwan(Chen and Lue,1987;Huang,1997).Despite its high species richness,the biology and ecology of the genusSphenomorphusare poorly known.Sexually dimorphic traits and/or female reproductive characteristics have been studied inS.incognitus(Huang,2010;Maet al.,2018),S.indicus(Huang 1996;Ji and Du,2000;Jiet al.,2006b),S.jagori(Auffenberg and Auffenberg,1989),S.maculates(Huang,1999),S.taiwanensis(Huang,1997,1998) andS.tonkinensis(Wanget al.,2013a).However,relatively detailed information is available only forS.indicusandS.incognitus.Incidental data on clutch or litter size have been reported forS.jagori(Auffenberg and Auffenberg,1989),S.taiwanensis(Chou and Lin,1992;Huang,1997) andS.tonkinensis(Wanget al.,2013a),but in none of these species have statistically meaningful data on maternal size,offspring(egg or neonate)size(mass),fecundity(clutch or litter size)and reproductive output (clutch or litter mass) already been collected and reported.

Sphenomorphus tonkinensisis a small oviparous scincid species described by Nguyenet al.(2011) based on nine specimens,eight from North Vietnam and one from South China(Hainan),with an unknown sex ratio.The skink occurs in southern China (Guangdong,Guangxi,Hainan and Jiangxi Provinces)and northern Vietnam,using habitats near streams in deep forest(Wanget al.,2013a;Qianet al.,2019;Figure 1).Earlier studies onS.tonkinensisonly presented very descriptive data on morphology and habitat use from a limited number of individuals(Nguyenet al.,2011;Wanget al.,2013a;Qianet al.,2019).From an earlier study by Wanget al.(2013a)on three populations ofS.tonkinensisin China we know that females lay 2-4 eggs per clutch.Here,we presented data forS.tonkinensisfrom Hainan,South China.Based on morphological measurements taken for adults in the field,clutches laid in the laboratory and eggs incubated at four constant temperatures ranging from 22°C to 28°C,we studied sexual dimorphism,female reproductive characteristics and embryonic thermosensitivity.Our aims were to show (1)sexual dimorphism in body size and shape,(2) the relationships among egg size (mass),clutch size,clutch mass and female size (snout-vent length,SVL),(3) the embryonic stage at laying,and (4) the thermal dependence of hatching success,incubation length and hatchling morphology.

Figure 1 Wet forest microhabitats used by S.tonkinensis are rich in dead branches and fallen leaves.The right plot shows an adult male(photo by Yu DU).

2.Materials and Methods

We collected 75 adults(30 females and 45 males larger than 44 mm SVL) ofS.tonkinensisin 2013 and 2014 from Wuzhishan,Hainan,southern China.We palpated all females and transported 19 reproductive females with enlarged follicles or oviductal eggs to our laboratory in Sanya.The remaining females and all males were released at their point of capture following the collection of morphological data.Skinks were individually weighed on a portable balance (Mettler-Toledo International Inc.,China),and measured with electronic digital calipers(Mitutoyo,Japan)for SVL,abdomen length(the distance between the fore-limb and the hind-limb),head length(from the snout to the anterior edge of tympanum),head width(taken at the posterior end of the mandible),fore-limb length(humerus plus ulna)and hindlimb length(femur plus tibia)(Sunet al.,2012).

The 19 reproductive females brought to the laboratory were individually housed in 500 mm× 300 mm × 200 mm plastic terraria placed in a room inside which temperatures varied from 20°C to 28°C.Each terrarium had a substrate consisting of moist soil (~60 mm depth) with cobblestones and fallen leaves.Females were able to regulate body temperature by using natural sunlight.Mealworms(larvae ofTenebrio molitor),house crickets (Achetus domesticus) and water enriched with vitamin and minerals were provided daily.

Females laid eggs from early February to late May.We checked the terraria at least thrice daily for freshly laid eggs after the first female laid eggs,thereby collecting and weighing eggs within 6 h post-laying.Of the 19 females,three laid the second clutch 42-47 d after laying the first clutch.Post-laying females were weighed and measured for SVL.We calculated relative clutch mass (RCM) by dividing clutch mass by the post-laying female mass and used the coefficient of variation[CV=100 × (standard deviation/mean)] to estimate withinclutch egg size variability(Guoet al.,2022).

We collected 42 fertilized eggs,of which 14(one from each of 14 clutches) were dissected to identify the Dufaure and Hubert’s(1961)embryonic stage at laying.The remaining 28 fertilized eggs were individually placed into covered plastic jars (50 mL),of which each had a substrate of moist vermiculite at -12 kPa (Maet al.,2018).All eggs were 2/3 buried in the substrate,with the surface near the embryo always kept upward.Eggs were equally assigned to four incubators (Binder,Tuttlingen,Germany),inside which temperatures were set at 22°C,24°C,26°C and 28°C,respectively.Temperatures were confirmed with Tinytalk temperature loggers(Gemini Pty,Australia)placed inside jars for a week.We rotated jars at 4-d intervals,thereby minimizing the influence of thermal gradients.We adjusted substrate water potential by weighing jars at the same time intervals.Incubation length was defined as the time between laying and pipping.Hatchlings were weighed and measured within 6 h post-hatching.

We used linear regression analysis to examine the relationship between a selected pair of dependent and independent variables and partial correlation analysis to examine the relationship between egg mass and clutch size while holding female SVL constant.We used ANCOVA to test for slope homogeneity of regression lines.We used unequal(for abdomen length using one-way ANOVA on regression residuals of the variable against SVL)or equal(for body mass,head length,head width,fore-limb length and hind-limb length using one-way ANCOVA with SVL as the covariate)slopes model to examine if an examined variable differed between the sexes.We used one-way ANOVA to examine if male and female adults differed in mean SVL and if mean values for mass at laying and incubation length differed among eggs incubated at different temperatures.We used one-way ANCOVA with egg mass at laying as the covariate to examine if hatchlings from eggs incubated at different temperatures differed morphologically at hatching.Prior to parametric analyses,all data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test,and for homogeneity of variances using Bartlett’s test.All statistical analyses were performed in Statistica 8.0 (StatSoft;Tulsa,OK,USA).Descriptive statistics are expressed as mean±standard error(SE)and range,and the significance level is set at 0.05.

3.Results and Discussion

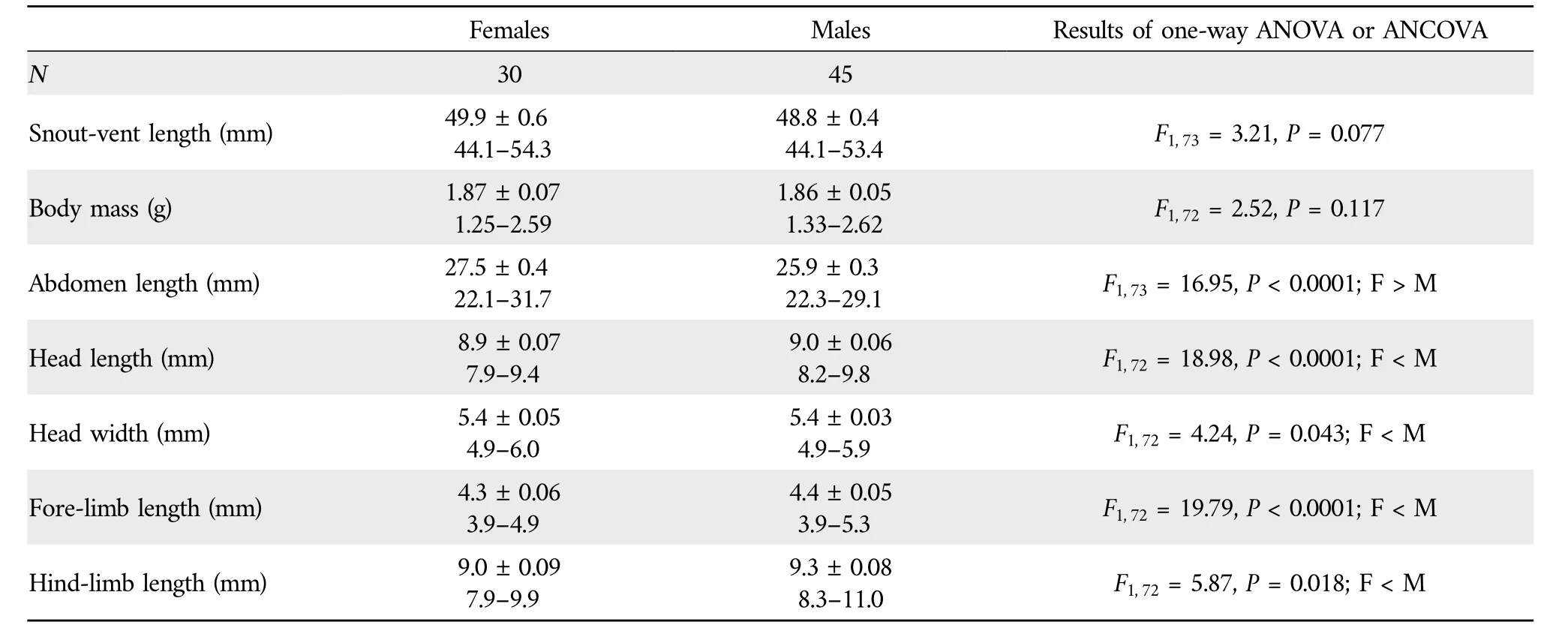

3.1.Body size and sexual dimorphismThe largest male was 53.4 mm SVL,and the largest female was 54.3 mm SVL.Both values are greater than the maximal sizes reported previously forS.tonkinensisfrom Hainan(48.8 mm;Qianet al.,2019),Chinese mainland (52.5 mm;Wanget al.,2013a) and North Vietnam(47.5 mm;Nguyenet al.,2011).The mean SVL was slightly greater in adult females(49.9 mm)than in adult males(48.8 mm),but the difference was not significant(Table 1).Accordingly,we come to a conclusion thatS.tonkinensisis among lizard species with sexual size monomorphism(SSM).SSM is one of three patterns of sexual size dimorphism(SSD),and the other two are male-biased (male-larger) SSD and female-biased (female-larger) SSD (Fairbairnet al.,2007;Dunham and Rudolf,2009;Corlet al.,2010).It is worth noting that patterns of SSD may vary even among populations of the same species.For example,adultS.incognitusdisplays malebiased SSD in Taiwan (Huang,2010) but SSM in Chinese mainland(Maet al.,2018).The evolution and maintenance of a SSD pattern often result from sexual differences in reproductive success relating to adult size (Coxet al.,2003).Within the family Scincidae,sexual selection via male contest competition is the key factor for male-biased SSD in the Chinese SkinkPlestiodon(Eumeces)chinensis(Lin and Ji,2000),the Blue-tailed SkinkPlestiodon elegans(Zhang and Ji,2004)and the Many-lined Sun SkinkEutropis(Mabuya)multifasciata(Jiet al.,2006a),and fecundity selection is the main factor for female-biased SSD inS.indicus(Ji and Du,2000),the Slender Forest SkinkScincella modestaand the Reeves’Smooth SkinkScincella reevesii(Yanget al.,2012).SSM occurs in a diverse array of lizard taxa including species of the families Agamidae(Jiet al.,2002a;Lin,2004;Quet al.,2011),Lacertidae(Liet al.,2006;Luet al.,2023),Sincidae (Lin,2005) and Shinisauridae(Heet al.,2011)where these two selective forces cancel each other out or male contest competition and physical constraints from maternal body size on reproductive output are both less evident.Here we add a scincid species to the list of lizards with SSM.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics,expressed as mean±SE and range,for snout-vent length,abdomen length,head length,head width,fore-limb length and hind-limb length of adult S.tonkinensis from Hainan,South China,and results of one-way ANOVA(for snout-vent length and abdomen length,with the latter analyzed by using unequal slopes model) and ANCOVA (for the remaining variables) using SVL as the covariate.

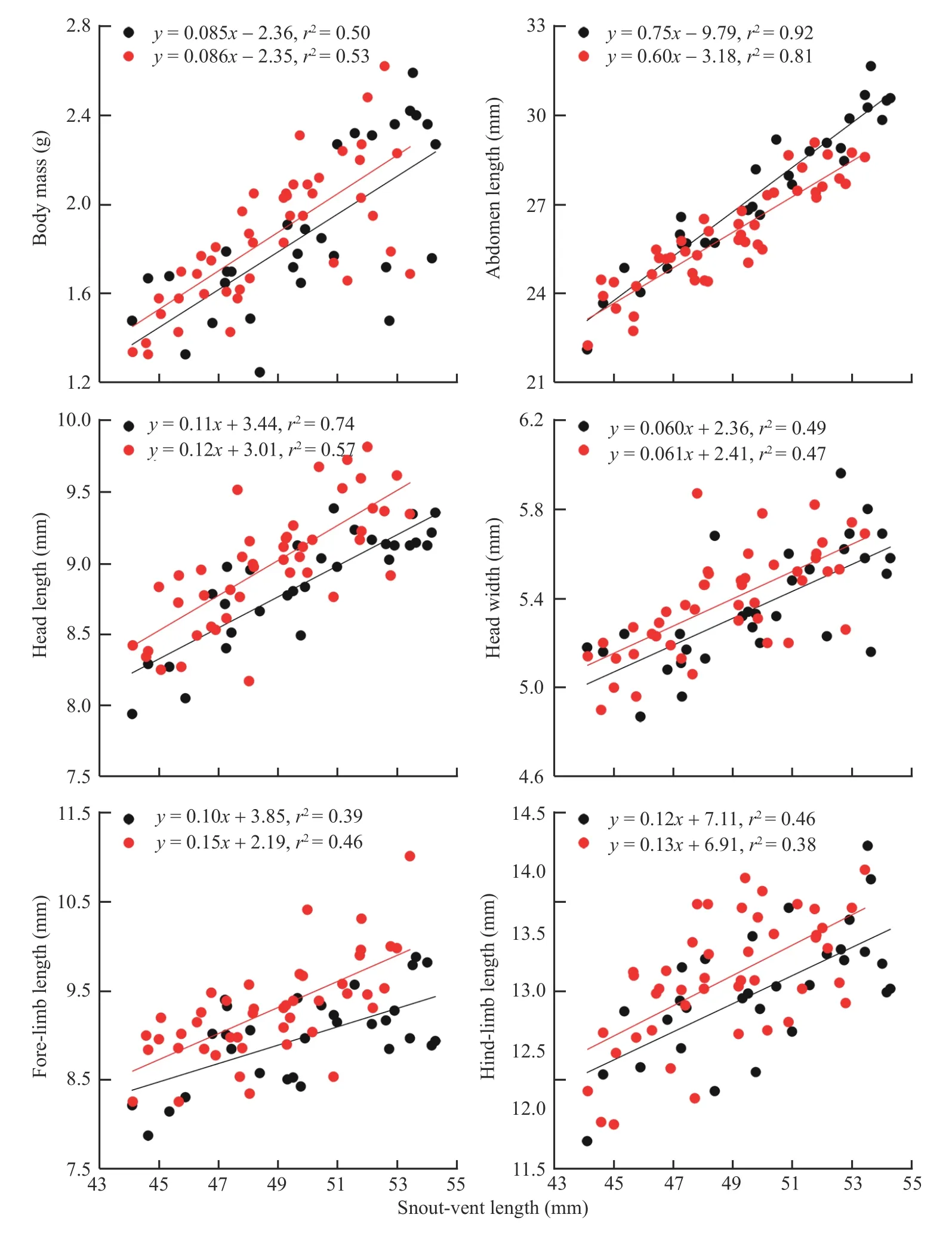

Abdomen length increased more rapidly with SVL for females than for males (ANCOVA for slope homogeneity,F1,71=6.13,P=0.015),whereas the rates at which body mass,head length,head width,fore-limb length and hind-limb length increased with SVL did not differ between the two sexes(ANCOVA for slope homogeneity;allP>0.215)(Figure 2).For a given SVL,body mass did not differ between the two sexes,abdomen length was greater in females than in males,and head length,head width,fore-limb length and hind-limb length were greater in males than in females(Table 1).These findings suggest that,as in nearly all lizard species studied thus far (Huang,1996;Olssonet al.,2002;Coxet al.,2003;Kratochvílet al.,2003;Lin,2005;Pincheira-Donoso and Tregenza,2011),adult males have larger heads and shorter abdomen (trunk) length than females of the same SVL inS.tonkinensis.Head and abdomen sizes are sexually dimorphic often because they are directly linked to the reproductive role of each sex (Bultéet al.,2008),although in some species the greater relative head size in males may have a secondary role in reducing resource competition between the sexes (Zhang and Ji,2004).Sexual dimorphism in appendage size is less commonly reported in comparisons of female and male lizards (Lin,2005).As inAnolislizards (Powell and Russell,1992;Malhotra and Thorpe,1997;Butler and Losos,2002),the Tropical Thornytail IguanaUracentron(Tropidurus)flaviceps(Vitt and Zani,1996),the Eastern Water SkinkEulamprus quoyii(Lin,2005),S.incognitus(Huang,2010;Maet al.,2018)and the Przewalski’s toad-headed lizardPhrynocephalus przewalskii(Zhao and Liu,2014),males have longer foreand hind-limbs than females of the same SVL inS.tonkinensis(Table 1).Data from the aforementioned species includingS.tonkinensissupport the conclusion that there is selection directly on limb length in lizards.

Figure 2 Linear regressions of body mass,abdomen length,head length,head width,fore-limb length and hind-limb length on SVL in S.tonkinensis.Black dots and lines represent adult females;red dots and lines represent adult males.

3.2.Female reproductive characteristicsTable 2 shows female reproductive characteristics ofS.tonkinensisfrom Hainan,South China.Females laid up to two clutches of 1-4 eggs each per egg-laying season from early February to late May.Clutch size was independent of female SVL (r2=0.06,F1,20=1.34,P=0.260).This finding suggests that,as inS.incognitusfrom Taiwan(Huang,2010),maternal size is not an important source of variation in fecundity (clutch size) inS.tonkinensisfrom Hainan.The mean clutch size was smaller inS.tonkinensis(2.5 in the first clutch,and 2.0 in the second clutch;Table 2)than inS.incognitus[5.2 in Chinese mainland(Maet al.,2018);~4.0 in Taiwan(Huang,2010)],S.indicus(7.2;Ji and Du,2000)andS.taiwanensis(5.0;Chou and Lin,1992;Huang,1997).The differences in fecundity betweenS.tonkinensisand the other three congeneric species could be partly due to the fact that adult females on average are smaller inS.tonkinensis(51 mm SVL;Table 1) than inS.incognitus(86 mm SVL;Huang,2010;Maet al.,2018),S.indicus(mean SVL=81 mm SVL;Ji and Du,2000)andS.taiwanensis(56 mm SVL;Huang,1998),because larger female skinks are generally more fecund than smaller ones and this is especially true in comparisons of congeneric species(Lin and Ji,2000;Du and Ji,2001;Sunet al.,2012).Data on egg mass and clutch mass have never been reported forS.tonkinensis.Here we found that neither clutch mass(r2=0.02,F1,20=0.51,P=0.485)nor egg mass(r2=0.01,F1,20=0.17,P=0.688)was related to female SVL.From these findings we may come to a conclusion that,as inS.incognitus(Maet al.,2018),female size is not an important source of variation in reproductive output or investment per offspring inS.tonkinensis.With female SVL held constant,egg mass was found to show no significant negative correlation with clutch size(r=-0.26,t=1.19,df=19,P=0.249).This finding suggests that,as in other oviparous sincid lizards such as the Long-tailed Sun SkinkEutropis longicaudata(Sunet al.,2012),S.modesta(Yanget al.,2012)andS.incognitus(Maet al.,2018),the egg size-number trade-off is not evident or eggs are well optimized for size inS.tonkinensis.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics,expressed as mean±SE and range,for post-laying female size and mass,egg mass,within-clutch variability[CV=100×(standard deviation/mean)]in egg mass,clutch size,clutch mass,and relative clutch mass in S.tonkinensis from Hainan,South China.N=the number of females laying eggs.

The mean RCM was smaller inS.tonkinensis(0.21;Table 1)than in other sincid species so far studied in China:0.25 inS.incognitus(Maet al.,2018),0.31 inP.elegans(Du and Ji,2001),0.33 inP.chinensis(Lin and Ji,2000),0.34 inE.longicaudata(Sunet al.,2012)and 0.72 inS.modesta(Yanget al.,2012).The proportion of variation in clutch mass explained by female SVL was much lower inS.tonkinensis(2%)than inS.incognitus(12%;Maet al.,2018),S.modesta(37%;Yanget al.,2012),E.longicaudata(42%;Sunet al.,2012),P.elegans(46%;Du and Ji,2001) andP.chinensis(51%;Lin and Ji,2000),and the proportion of variation in clutch size explained by female SVL was much lower inS.tonkinensis(6%)than in the Ixbaac Brown Forest SkinkScincella(Sphenomorphus)cherriei(12%;Goldberg,2008),S.incognitus(18%;Maet al.,2018),E.longicaudata(35%;Sunet al.,2012),P.elegans(37%;Du and Ji,2001),S.modesta(40%;Yanget al.,2012),P.chinensis(52%;Lin and Ji,2000)andS.taiwanensis(86%;Huang,1997).The above comparisons allow a conclusion that selection on increased maternal body size and thus increased body volume available to hold eggs is comparatively weak inS.tonkinensis.

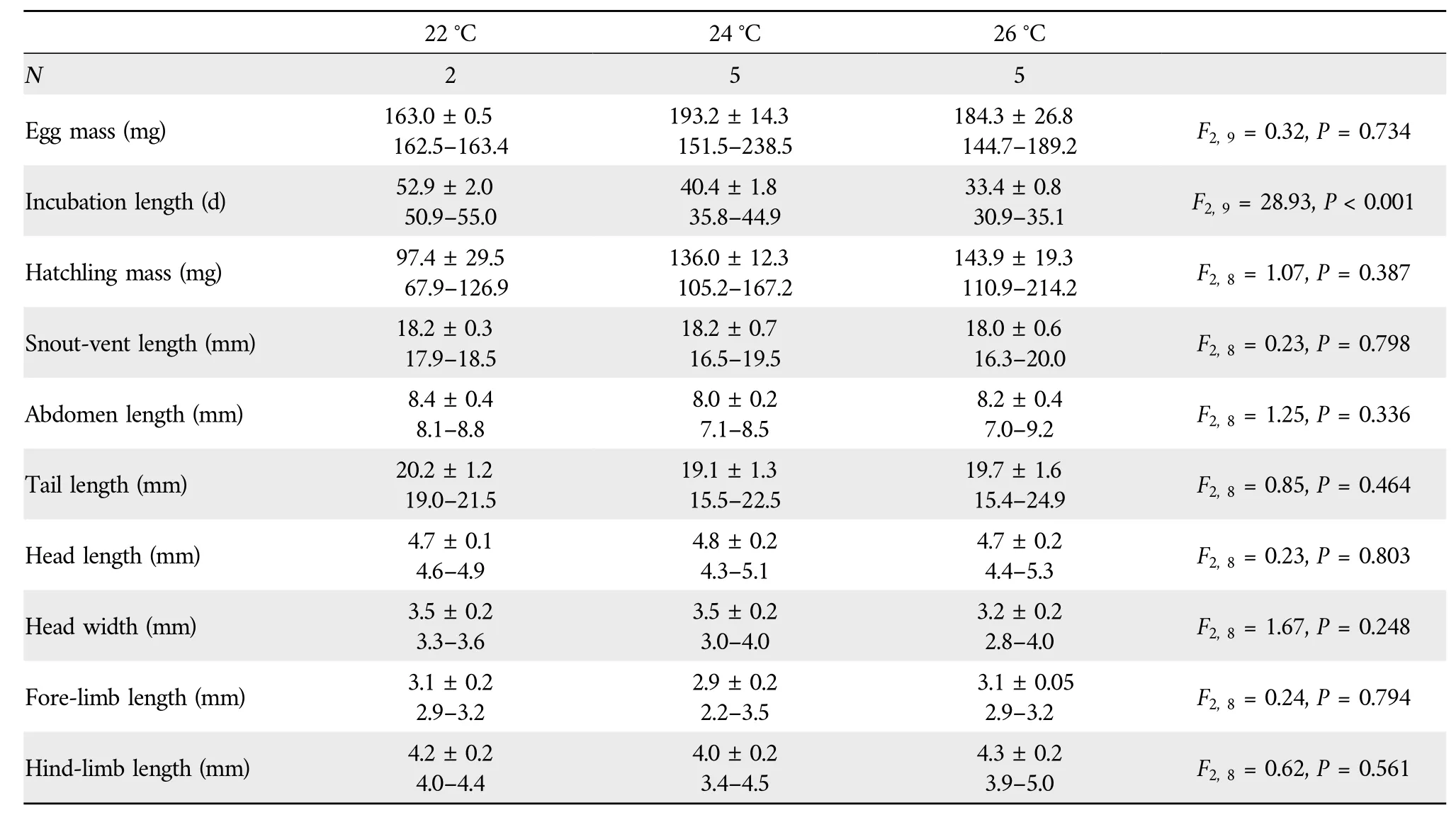

3.3.Egg incubation and hatchling phenotypeEmbryonic stages at laying ranged from Dufaure and Hubert’s (1961)stage 30 to 31,with a mean of 30.1.Embryonic stage at laying is an important source of variation in incubation length in lizards(Wanget al.,2013b).However,incubation length at any given temperature may vary among species that differ in phylogeny,egg size,distribution and/or habitat use(Luet al.,2006;Linet al.,2010;Liet al.,2012,2013;Sunet al.,2013).For example,the mean incubation length at 22°C is longest inS.incognitus(~76 d;Maet al.,2018) and shortest inS.modesta(~31 d;Liet al.,2012),withS.tonkinensis(~53 d;Table 3) in between.It is worth noting that the mean embryonic stage at laying does not differ betweenS.incognitus(31.3;Maet al.,2018)andS.modesta(31.1;Luet al.,2006)and is only about one stage earlier inS.tonkinensisthan in the other two species.The finding that incubation length can be longer in congeneric species with more advanced embryos at laying suggests that factor(s) other than embryonic stage at laying can affect the rate of embryonic development.

Table 3 F values and significance levels of one-way ANOVA (egg mass and incubation length) and ANCOVA (hatchling mass,snout-vent length,abdomen length,tail length,head length,head width,fore-limb length,and hind-limb length)with temperature the fixed factors and egg mass at laying as the covariate.

None of the eggs at 28°C hatched,suggesting that the upper thermal threshold for embryonic development is lower inS.tonkinensisthan inS.incognitusandS.modestaof which eggs can be successfully incubated at 28°C (Luet al.,2006;Liet al.,2012;Maet al.,2018).The upper thermal threshold for egg incubation is lower in lizards using shaded habitats than in those using opened habitats.For example,temperatures higher than 28°C adversely affect egg incubation inS.incognitusandS.modestausing habitats along forest edges(Luet al.,2006;Liet al.,2012;Maet al.,2018),whereas temperatures slightly higher than 30°C do not dramatically reduce hatching success in the Oriental Garden LizardCalotes versicolor(Jiet al.,2002b) and the White-striped Grass LizardTakydromus wolteri(Pan and Ji,2001)using more open habitats.Hatching success was much lower at 22°C(25%)than at 24°C(62.5%)and 26°C(62.5%), suggesting that the lower thermal threshold for egg incubation is higher inS.tonkinensisthan inS.incognitusandS.modestaof which eggs can be successfully incubated at 22°C (Liet al.,2012;Maet al.,2018).From the above comparisons we may come to a conclusion that the range of suitable incubation temperatures is narrower in forest skinks such asS.tonkinensisusing habitats in the deep forest than in other closely related species using habitats along forest edges where the mean and amplitude of thermal fluctuations are relatively great.

We found that inS.tonkinensisthe mean incubation length was shortened by 12.5 d at the changeover from 22°C to 24°C,and by 7.0 d at changeover from 24°C to 26°C(Table 3).Such a thermal dependence of incubation length has been repeatedly reported in a diverse array of reptilian taxa including turtles(Jiet al.,2003,Duet al.,2010),lizards(Wanget al.,2013b;Shenet al.,2017),snakes(Ji and Du,2001;Linet al.,2010) and crocodilians (Charruau,2012;Liuet al.,2023).Hatchlings from eggs incubated at 22°C,24°C and 26°C did not differ morphologically (Table 3),suggesting that incubation temperatures within a certain range do not differentially affect hatchling morphology inS.tonkinensis.A similar result has been reported for crocodilians (Liuet al.,2023),turtles(Du and Ji,2003;Jiet al.,2003),lizards(Chenet al.,2003;Andrewarthaet al.,2010;Liet al.,2013)and snakes(Chen and Ji,2002;Lin and Ji,2004;Linet al.,2008;Luet al.,2009).In nearly all reptilian species studied thus far,incubation temperature has no role in modifying hatchling traits as long as eggs or embryos are not exposed to extreme temperatures for prolonged periods of time.A certain degree of thermal insensitivity of hatchling phenotype is important for ectothermic animals including reptiles where embryos are unlike to complete development under constant-temperature conditions.

4.Conclusions

Sphenomorphus tonkinensisis a sparsely studied species.Here we used adults collected from Hainan,South China to study sexual dimorphism,female reproduction and egg incubation in this species.From this study we may come to the following conclusions aboutS.tonkinensis.First,the skink is basically a sexually size-monomorphic species with sexual dimorphism in head size,abdomen length and limb size.Second,females larger than 44 mm SVL lay up to two clutches of 1-4 eggs each per egg-laying season from early February to late May.Third,egg mass,clutch size and clutch mass are independent of female SVL and,with female SVL held constant,the negative correlation between egg size(mass)and clutch size is not significant.Fourth,embryonic stages at laying range from Dufaure and Hubert’s stage 30 to 31,and the mean incubation length at a given temperature is much shorter inS.tonkinensiscompared toS.incognitus,a congeneric species with a slightly more advanced embryonic stage at laying.Last,incubation temperatures across the range from 22°C to 26°C do not differentially affect hatchling morphology.

AcknowledgementsOur experimental procedures complied with the current laws on animal welfare and research in China.We thank Zhongyin CHEN,Xiangmo LI and Qize LIU for assistance during the research.This work was supported by grants from the Special Foundation for Basic Work of the Science and Technology Ministry of China(2022FY100500-2),Hainan Key Program of Science and Technology (ZDXM20110008) and Hainan Specially Supporting Discipline of Zoology.

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- Oxygen Availability Affects Behavioural Thermoregulation of Turtle Embryos

- Next-generation Sequencing of MHC Class I Genes Reveals Trans-species Polymorphism in Eutropis multifasciata and Other Species of Scincidae

- Evidence for Expensive Tissue Hypothesis in the Asian Common Toad(Duttaphrynus melanostictus)

- Redefinition of the Odorrana versabilis Group,with a New Species from China (Anura,Ranidae, Odorrana)

- A New Species of the Genus Nanorana Günther,1896 (Anura:Dicroglossidae) from Hengduan Mountains of China

- Response of Distribution Range Against Climate Change and Habitat Preference of Four National Protected Diploderma Species in Tibetan Plateau