Examination of the poverty-environmental degradation nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa

2023-10-24SadatDaakiSSEKIBAALATwahaAhmedKASULE

Sadat Daaki SSEKIBAALA, Twaha Ahmed KASULE

Department of Economics, Islamic University in Uganda, Mbale, 2555, Uganda

Keywords:Environmental degradation Poverty Vicious cycle hypothesis Sub-Saharan Africa Generalized method of moments (GMM)approach

A B S T R A C T

1.Introduction

Poverty is a global phenomenon, which is a significant cause and effect of global environmental problems.Poor people are short-run maximizers who focus on meeting their present needs at the cost of future.In doing so, they often destroy the environment for their immediate survival.Due to the continuous environmental degradation, the poor often find themselves with irreversible adverse effects, which often push them into further poverty (Amoako-Asiedu,2016).According to Rai (2019), the poverty-environmental degradation nexus is explained in a way that both of them can be a cause and effect of each other and often bound together in a mutually influencing vicious cycle, which often leads to a poverty-environmental degradation trap (Barbier and Hochard, 2019).The mutually reinforcing vicious cycle can lead to a worsening ‘downward spiral’ of poverty and environmental degradation (Barbier and Hochard,2018a).

According to Rakshit et al.(2023), the incidence of extreme poverty slightly declined in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA),due to the region’s high economic progress, thereby generally slowing down the overall global extreme poverty reduction progress.Recent estimates suggest that SSA’s poverty rate decreased by 15.8% between 1990 and 2018,which translates to a decline in SSA’s people living below the 1.90 USD per day poverty line from 56.0% in 1990 to 40.2% in 2018 (World Bank, 2020a).However, poverty reduction has been much slower at 3.20 and 5.50 USD per day poverty lines.From 1990 to 2018, SSA’s poverty fell by 9.5% from 76.1% to 66.6% at the 3.20 USD per day poverty line and by 3.3% from 89.3% to 86.0% at the 5.50 USD per day poverty line (World Bank, 2020a).Perhaps even more alarming report of World Bank (2020b) suggested that people with low incomes in SSA are also more likely to be exposed to different shocks, including threats such as armed conflicts, climate change, and global economic recessions like the one caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.World Bank estimates that half of the people who had escaped poverty between 2013 and 2018 went back into extreme poverty due to the economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, with an estimated 4.0×107SSA population being pushed back into poverty(Kharas, 2020).

On the other hand, Ssekibaala et al.(2022) suggested that environmental degradation is often defined by air and water pollution and land degradation.Air pollution refers to air contamination, due to the persistent emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and particulate matter into the atmosphere.CO2is the most common GHGs.Whereas SSA’s CO2emissions remained less than 5.0% of total global CO2emissions between 1990 and 2018, Wang and Dong(2019) suggested that, if unchecked, SSA may become major emitters in the future.Furthermore, according to Amegah and Agyei-Mensah (2017), urban air quality in SSA is deteriorating, due to the increased concentration of particulate matter in the atmosphere.Data from the Health Effects Institute and Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (2020)suggested that with around 45.0 μg/m3annual average exposure in 2019, PM2.5 concentration in SSA exceeded the WHO-recommended level, at 10.0 μg/m3.Amongst the SSA, Nigeria experienced the highest PM2.5 exposure in 2019, at 70.4 μg/m3.Lastly, deforestation is a leading cause of land degradation and involves the loss of a country’s natural forest area without afforestation (Ssekibaala et al., 2021).FAO (2020) indicated that over 4.2×108hm2of forest area has been lost since 1990.Although the rate of deforestation is gradually declining in other regions, it is increasing in SSA.FAO (2020) suggested that between 2010 and 2020, Africa had the highest annual net forest loss(at around 3.9×107hm2), up from 3.4×107hm2per year lost during 2000-2010 and 3.3×107hm2during 1990-2000.

Based on the above statistics, SSA is the poorest region in the world and is on course to gradually increase environmental degradation (CO2and PM2.5 emissions and deforestation).The severity of environmental degradation and poverty in SSA makes the region an ideal case study for the analysis of poverty-environmental degradation nexus.Endemic poverty in SSA most likely limits the survival options of the poor (Baloch et al., 2020a), thereby inducing poor people to over-exploit environmental resources at rates incompatible with long-term sustainability (Amoako-Asiedu, 2016), and lowering their productivity.Consequently, the poor become poorer when environmental degradation strains their income streams (Baloch et al., 2020a).Besides, poor people lack the financial resources to mitigate the effects of environmental degradation, thereby keeping them in a poverty trap.

The relationship between environmental degradation and poverty has increasingly become the focus of national strategic decision-making in recent years (Khan, 2021).However, the literature on the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation is theoretically conflicting and empirically inconclusive (Cheng et al., 2018; Kousar and Shabbir, 2021; Koçak and Çelik, 2021).Whereas several theoretical and empirical analyses that address poverty and environmental degradation have been performed over the years, there is a dearth of empirical literature on the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation, specifically in SSA, despite the region being the poorest in the world.Besides, the available empirical research on poverty emphasizes using the poverty lines as a measure.However, according to Jin et al.(2020), the poverty line measure considers only two aspects, measurement and identification, which may not appropriately measure poverty.Jin et al.(2020) suggested that the best approach should consider a comprehensive measurement of poverty conditions from three dimensions: breadth, depth, and intensity,and emphasized the dimensional analysis of poverty alleviation path and dynamic characterization in identifying poverty-reducing factors.Haughton and Khandker (2009) suggested that the poverty gap index provides a more robust way of describing poverty since it considers the extent to which individuals, on average, fall below the poverty line and expresses it as a percentage of the poverty line.

In this study, we extended an analytical framework to explore the interlinkages between poverty and environmental degradation to reveal the existence of a vicious cycle in the poverty-environmental degradation nexus in SSA.We identified the gaps in the existing literature on the nexus between poverty and environmental degradation and discussed the implications of the combined effects of poverty and other endogenous factors on environmental degradation in SSA.We also analyzed the mediating role of institutional quality on the poverty-environmental degradation nexus and identified other macroeconomic conditioning factors that influence the nexus.Furthermore,whereas most literature on environmental degradation has focused on air pollution indicators, Ssekibaala et al.(2022)showed the importance of considering several aspects of environmental degradation, such as land degradation,deforestation, and water pollution, as their effects may differ.Therefore, unlike previous studies on environmental degradation, we employed several alternative indicators of environmental degradation to derive conclusions about the effect of poverty on environment in this study.Albeit aiming to close the dearth of literature on the povertyenvironmental degradation nexus in SSA, this study also offered important policy implications for SSA and other developing regions.

2.Literature review

2.1.Vicious cycle in the poverty-environmental degradation nexus

According to Barbier and Hochard (2018a) and Baloch et al.(2020a), the poverty-environmental degradation nexus, particularly in developing countries, follows a vicious cycle whereby poverty is a significant cause and effect of environmental degradation.In addition, Barbier and Hochard (2019) further observed that when the nexus follows a vicious cycle, it often leads to a poverty-environmental degradation trap where poverty and environmental degradation remain stagnant.The vicious cycle hypothesis is based on the assumption that poor people in developing countries are heavily dependent on natural resources and the environment for their livelihood (Barbier and Hochard,2018a).As such, Broad (1994) suggested that the conditions for the validity of the vicious cycle hypothesis argument are under below.Firstly, poverty is viewed as a primary cause of environmental degradation.Secondly, poor people are short-term maximizers and cannot, in their present state, consider the future benefits of environmental conservation.Therefore, the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation depends on choices made by the poor, who, due to their lack of access to natural resources, usually tend to over-exploit the resources at their disposal, thereby causing environmental degradation, which keeps the poor people in a poverty-environmental degradation trap.

The critiques of the vicious cycle and the poverty-environmental degradation trap hypothesis suggest that environmental degradation may not only depend on the decisions of people with low incomes.Broad (1994) indicated that there can be cases where poor people advocate for environmental protection.Firstly, when the poor people understand that their livelihoods depend on the environment.Secondly, the length of time that poor people have lived in an area increases their ties to the environment.And thirdly, the presence of an effective civil society increases environmental advocacy.People create a bond with the environment and a feeling of responsibility to protect it irrespective of poverty status.As such, it may be erroneous to conclude that poverty is the leading cause of all environmental degradation.Therefore, the vicious cycle hypothesis seems too simplistic to explain the complex relationship between poverty and environmental degradation (Meher, 2023).Barbier and Hochard (2018a) also argued that it is essential to ask why the poor are poor in the first place.Thus, poverty-environmental degradation nexus is more complex.

The mutual interrelatedness between poverty and environmental degradation may further precipitate a downward spiral (Barbier and Hochard, 2018a; Masron and Subramaniam, 2018; Rai, 2019).Therefore, as poverty and environmental degradation continue to influence each other, the situations for both become worse than initially.Ekbom and Bojö (1999) argued that poverty forces the poor to engage in environmentally damaging behavior, which lowers the productivity of environmental resources and doubles as the source of income for people who are experiencing poverty.In the end, this forces the poor people into further poverty.In addition, some literature suggests that the nature of poverty and environmental degradation as either endogenous or exogenous factor determines the feedback loops essential in defining the linkages between poverty and environmental degradation.However, Rai(2019) suggested that generalizing the poverty-environmental degradation nexus under the downward spiral framework is also quite simplistic.Also, conceptualizing the link between poverty and environmental degradation as a downward spiral involves considering other factors (Prince et al., 2017; Rai, 2019).Barbier and Hochard (2018b)referred to these additional factors as conditioning factors that may involve economic, social, and institutional dimensions.According to Barbier and Hochard (2018b) and Rai (2019), these conditioning factors form a web of interrelations that influence the nexus.These demonstrate how poverty and environmental degradation reinforce each other and support the downward spiral hypothesis (Barbier and Hochard, 2016).However, Meher (2023) found no empirical evidence that poverty affects forest degradation, while found evidence of forest degradation with the increase in income, so he concluded that it is non-poor households than poor who are responsible for forest degradation.The findings by Meher (2023) do not support the downward spiral hypothesis and question the assumption that poverty alleviation is an essential part of avoiding forest degradation.

Further, Barbier and Hochard (2018a) suggested that the downward spiral depends on several other external conditioning factors that affect the poverty-environmental degradation nexus.In this case, the conditioning factors are external.They can be economic, social, and institutional factors, mainly beyond poor people’s or individual households’ control.Among the conditioning factors, Barbier and Hochard (2018a) cited the social and institutional factors such as civil unrest and conflict, political instability, governance, migration and demographic changes,inequality, and social justice, which are conditioning factors that also interact with the nexus to cause the downward spiral.In addition, other environmental factors, such as climate change, natural disaster risk, drought, and climate change, may compound the nexus leading to adverse outcomes on agriculture productivity and human health (Scherr,2000).

Further, Yusuf (2004) suggested that institutional quality, education, and population growth mediate the bidirectional relationship between poverty and environmental degradation.Good institutions enable the poor to adopt sustainable activities that can prevent environmental degradation (Khan, 2021).Hence, improving institutional quality reduces both poverty and environmental degradation.Baloch et al.(2020b) showed that poverty degrades ecological footprints and asserted that excessive use of natural resources in food, water, and energy to sustain livelihood might lead to environmental degradation in SSA.Asongu (2018) showed that increasing CO2emissions negatively impact inclusive human development and hinder poverty and inequality reduction.

Furthermore, Rakshit et al.(2023) examined the impact of energy use on poverty and found that energy use significantly reduces poverty and the ecological footprint in the region, while Kousar and Shabbir (2021) suggested that energy use partially mediates the long-run relationship between environmental degradation and poverty.Finally,Koçak and Çelik (2021) also illustrated that energy use significantly contributes to PM2.5 emissions.

Besides, Ehigiamusoe et al.(2022) illustrated the effect of income inequality on the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation in different countries.They found that income inequality and poverty increase environmental degradation generally.However, by splitting the panel into income groups, they found that income inequality can mitigate environmental degradation in high-income groups but increases it in low and middle-income groups.Ehigiamusoe et al.(2022) showed that income inequality and poverty are significant determinants of environmental pollution.Hence, efforts to abate environmental degradation should give adequate attention to poverty and inequality.

Furthermore, since environmental degradation is closely associated with human activities, it is vital to understand the impact of industrialization on the relationship between environmental degradation and poverty.Although a flourishing body of literature have investigated the linkage between industrialization and environmental degradation across countries, the literature is limited in the context of SSA region (Lin et al., 2015; Wang and Dong, 2019).Industrialization also influences the quality of environment through the emission of dangerous gases and fumes, as well as water pollution (Wang and Dong, 2019).The accelerating pace of industrial development has reduced poverty at the expense of higher environmental risk.In addition, Esso and Keho (2016) suggested that the lack of advanced technology has impeded the tapping of green energy potential and also has increased energy consumption from fossil fuels in industrialization.

2.2.Empirical literature on the nexus between poverty and environmental degradation

Whereas several studies have examined the factors determining environmental degradation in developing countries,including those in SSA, only a few studies have explored the intricacies between poverty and environmental degradation.Among them, Khan and Khan (2016), Azizi and Farzam (2022), Ehigiamusoe et al.(2022), Meher(2023), and Rakshit et al.(2023) revealed varied conclusions on the relationship between poverty and environment,as well as how other macroeconomic and institutional factors affect the poverty-environmental degradation nexus.

Masron and Subramaniam (2018) suggested that poverty is the leading cause of environmental degradation in developing countries and poverty alleviation can significantly improve the quality of environment.In contrast, Kousar and Shabbir (2021) revealed that environmental degradation significantly contributes to poverty; therefore, the focus must be on improving environmental quality, which might lead to poverty reduction.Khan (2021) showed that poverty and environmental degradation can be reduced simultaneously by improving institutional quality.Awad and Warsame(2022) investigated the poverty-environment nexus and found a bidirectional causality relationship between poverty and the ecological footprint for the global panel and the African region, while no causality was detected for the developed regions.Similar conclusions are also presented by Ehigiamusoe et al.(2022).Besides, Koçak and Celik,(2021) also explored the relationship between poverty and air pollution (PM2.5) in Sub-Saharan African countries and found a trade-off between poverty and PM2.5 emissions in SSA.However, Meher (2023) examined whether poverty causes forest degradation in India, and found no empirical evidence that poverty affects forest degradation but found evidence of an increase in forest degradation as income increases.Meher (2023) concluded that the nonpoor households are responsible for forest degradation than the poor.

From the above studies, we can say that because policies directed towards poverty eradication may reflect in the poor quality of environment, some policy measures aiming to preserve environment may lead to the expansion of poverty.However, because findings by Meher (2023) do not support the hypothesis and question the assumption that poverty is an essential part of environmental degradation, this means that the poverty-environmental degradation nexus is an empirically unsettled research agenda.

2.3.A conceptual model of the poverty-environmental degradation nexus

From the literature review, we developed a conceptual model to explain the poverty-environmental degradation nexus (Fig.1).In the conceptual model, R1 and R2 are exogenous conditioning factors that directly determine poverty and environmental degradation.Hypothesis R1 is for exogenous conditioning factors determining poverty, while hypothesis R2 is for exogenous conditioning factors determining environmental degradation.These include socioeconomic factors such as population growth rate, suggested by Ekbom and Bojö (1999); education, by Reardon and Vosti (1995); industrialization, by Masron and Subramaniam (2018); as well as income inequality, suggested by Ekbom and Bojö (1999).We also follow Rai (2019) to include institutional quality factors: governance effectiveness,control of corruption, freedom and civil liberty, and democracy.

Fig.1.Conceptual model for the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation.R1 represents exogenous conditioning factors that directly determine poverty; R2 represents exogenous conditioning factors that directly determine environmental degradation; H1 represents that poverty causes environmental degradation; H2 represents that environmental degradation causes poverty; H3a represents that poverty influences the environmental degradation endogenous factors of fossil fuel energy use and fuelwood energy use; H3b represents that the fuel energy use and fuelwood energy use further influence air pollution and land degradation; H4a represents that air pollution influences health; H4b represents that land degradation influences agricultural productivity; and H5 represents that environmental degradation induces poverty.

Hypothesis H1 discusses poverty as a direct cause of environmental degradation.We assumed that poverty leads to environmental degradation regardless of what causes it.Baloch et al.(2020b) stated that poor people’s livelihoods depend entirely on the natural environment.As such, prolonged dependence usually leads to over-exploitation and may cause environmental degradation.Otherwise, poverty will have a “direct effect” on environmental degradation.

On the other hand, hypothesis H2 suggests that environmental degradation causes poverty.According to Rai (2019),this is a “victims” hypothesis, which suggests that poor people are victims of environmental degradation.Barbier and Hochard (2018a) indicated that this hypothesis is validated by the fact that poor people are landless.Hence, they settle on marginal lands and cultivate poor soils, and they are politically marginalized and less educated.In addition,environmental degradation makes it difficult for poor people to escape poverty.Therefore, hypothesis H2 explains how environmental degradation leads to poverty.

Hypotheses H3a and H3b suggest that poor people are agents of environmental degradation through their actions and decisions.According to these hypotheses, poor people act in ways that degrade the environment.For example,Barbier and Hochard (2018a) suggested that poor people are often forced to exploit new fragile natural resources in ways that cause environmental degradation due to their limited resources, assets, and investments.For example,Fayzieva (2003) suggested that areas with a high concentration of poor people, especially rural regions, suffer from a unique form of environmental degradation resulting from the actions of poor people.Therefore, hypotheses H3a and H3b indicate that poor people act in ways that indirectly cause environmental degradation.

Hypotheses H4a and H4b are the endogenous causes of poverty.These hypotheses explain how the consequences of environmental degradation may lead to poverty.Hypothesis H4a explains how indoor and outdoor air pollution have adverse effects on health, such as infant mortality and increased household expenditures on health.Hypothesis H4b illustrates how land degradation and deforestation affect agricultural productivity, often leading to low agricultural output.The total effect of hypotheses H4a and H4b on poverty is further explained by hypothesis H5,which suggests that environmental degradation induces poverty.From this hypothesis, we can conclude that the consequences of environmental degradation cause poverty.

As can be seen from the conceptual model, the vicious cycle is represented by the combination of H1 and H2.However, considering an ideal discussion, all hypotheses contribute to the nexus, which illustrates how multiple exogenous conditioning factors and endogenous factors form a web of interactions that explain the povertyenvironmental degradation nexus.

3.Methodology

3.1.Empirical model

Based on the conceptual model in Figure 1, we hypothesized direct relationship between environmental degradation and poverty.Specifically, we suggested that poverty causes environmental degradation.On the other hand, we illustrated that environmental degradation causes poverty.We further hypothesized indirect relationship between environmental degradation and poverty in which poverty induces exogenous causes of environmental degradation through actions and decisions of the poor.Besides, we also considered the impact of environmental degradation on poverty.

where ED is the level of environmental degradation; POV is the level of poverty; POV·EDENDis an interaction term between poverty and endogenous causes of environmental degradation; and ED·POVENDis an interaction term between environmental degradation and endogenous causes of poverty.

Furthermore, we also considered other exogenous conditioning factors that determine poverty and environmental degradation.For this model, we usedXas a vector to indicate other exogenous conditioning factors.

Therefore, Equation 1 becomes:

and Equation 2 becomes:

From Equations 3 and 4, the empirical equations are:

where EDitis the level of environmental degradation of theithcountry (i=1, 2, …,N) in thetthyear (t=1, 2, …,T);POVitis the level of poverty of theithcountry in thetthyear;αiis the country-specific intercept;θtis the time-specific intercept;εitandμitare the error terms that are independent and identically distributed for EDitand POVit,respectively;β1andλ1are the coefficients of estimation for poverty and environmental degradation, respectively;φis a vector for coefficients of estimation for the interaction terms; andνis a vector for coefficients of estimation for the other exogenous conditioning factors (Xit).

From Equations 5 and 6, POV·EDENDillustrates how environmental degradation can be induced by the actions and decisions of poor people, while ED·POVENDshows how poverty can be caused by environmental degradation.For POV·EDEND, we considered the interaction term between poverty and fossil fuel energy use (POV·FFEU) and the interaction term between poverty and fuelwood energy use (POV·FWEU).Furthermore, for ED·POVEND, we considered the interaction term between environmental degradation and adverse effects on health represented by infant mortality rate (ED·IMR) and household health expenditure (ED·HHE), as well as with agricultural productivity(ED·AP).Besides,Xitis a vector for exogenous conditioning factors, which act as control variables.For this study,we used a population growth rate, education, industrialization, and income inequality as the social-economic control factors.Furthermore, we used governance effectiveness, control of corruption, freedom and civil liberty, and democracy as proxies for institutional quality factors.Furthermore, the defining feature of dynamic panel modelling is the inclusion of one or more lags of the dependent variable on the right-hand side of the regression equation.This means that the entire history of the model is itself contained within the lagged dependent variable(s).This inclusion changes the interpretation of the right-hand side variables, which now indicate contemporaneous effects conditional on the history of the independent variables, while the estimated effect of the lagged dependent variable also gives the possibility to determine the cumulative influence of the measured past.Furthermore, estimating with a lagged dependent variable provides a measure of persistence in the dependent variable.Therefore, by introducing the control variables and the lagged dependent variables into the model, the dynamic model specifications are:

whereLis the natural log; EDi,t-1and POVi,t-1are the lagged dependent variables for environmental degradation and poverty, respectively;λ0andβ0are the coefficients for the lagged dependent variable of EDi,t-1and POVi,t-1,respectively; FFEU is the abbreviation of fossil fuel energy use; FWEU is the abbreviation of fuelwood energy use;PGR is the abbreviation of population growth rate; EDU is the abbreviation of education; IND is the abbreviation of industrialization; II is the abbreviation of income inequality; GE is the abbreviation of governance effectiveness; COC is the abbreviation of control of corruption; FCL is the abbreviation of freedom and civil liberty; DEM is the abbreviation of democracy; HHE is the abbreviation of household health expenditure; IMR is the abbreviation of infant mortality rate; AP is the abbreviation of agricultural productivity;ρ1,ρ2, andρ3are the coefficients of estimation for endogenous causes of environmental degradation in POVit,FFEUit, and FWEUit, respectively;δ1,δ2,δ3, andδ4are the coefficients of estimation for endogenous causes of poverty in EDit,HHEit, IMRit, and APit, respectively;φ1andφ2are the coefficients of estimation for the interaction terms as used; andν1,ν2,ν2,ν4,ν5,ν6,ν7, andν8are the coefficients of estimation for the control variables used.

3.2.Data sources and description of variables

In this study, we used annual panel data from 41 countries in SSA during 1996-2019.The selected countries included Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Comoros, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea,Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar,Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Senegal,Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Eswatini, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.We selected both the countries and the period of study, based on data availability for all variables.Following Rakshit et al.(2023), we adopted the poverty gap index as a measure of poverty.According to Haughton and Khandker (2009),the PGI considers the extent to which individuals, on average, fall below the poverty line and expresses it as a percentage of the poverty line.Assuming the poverty gapGiis estimated as:

whereGiis the poverty gap;Zis the poverty line; andyiis the income of each poor individual.

where PGI is the poverty gap index; andMis the total population of a given country.The poverty gap is considered to be zero for individuals with income above the poverty line.

For environmental degradation, three indicators were used: PM2.5 emissions, CO2emissions, and deforestation.PM2.5 emissions and CO2emissions are indicators of indoor and outdoor air pollution, while deforestation indicates land degradation.Firstly, we followed Tenaw and Beyene (2021) and Rakshit et al.(2023) to represent global air pollution by using per capita CO2emissions.Secondly, we followed Wu (2017) and Koçak and Celik (2021) to use the natural log of fine particulate matter (i.e., PM2.5) emissions.Finally, we followed Bhattarai and Hammig (2004)and Meher (2023) to use the natural log of deforestation as an indicator of environmental degradation.

where RD is the rate of deforestation; andFitandFi,t-1are the total forest area in the current and previous periods(km2), respectively.

We also used fossil fuel energy use and firewood energy use as proxies for energy consumption, indicating how the poor’s actions regarding energy use cause environmental degradation.Among other variables, for adverse effects on health in developing countries, health implications caused by environmental degradation impact household expenditure.Furthermore, from the literature, we understood that environmental degradation may affect the health of the poor through the spread of disease (Genowska et al., 2015).Therefore, we used infant mortality rate (IMR), the number of infants dying before one year per 1000 live births yearly.Further, environmental degradation may increase poverty by affecting agricultural productivity.Therefore, to capture this relationship, we followed Fulginiti et al.(2004) to use the “value of agriculture gross production”, a measure of agricultural productivity.

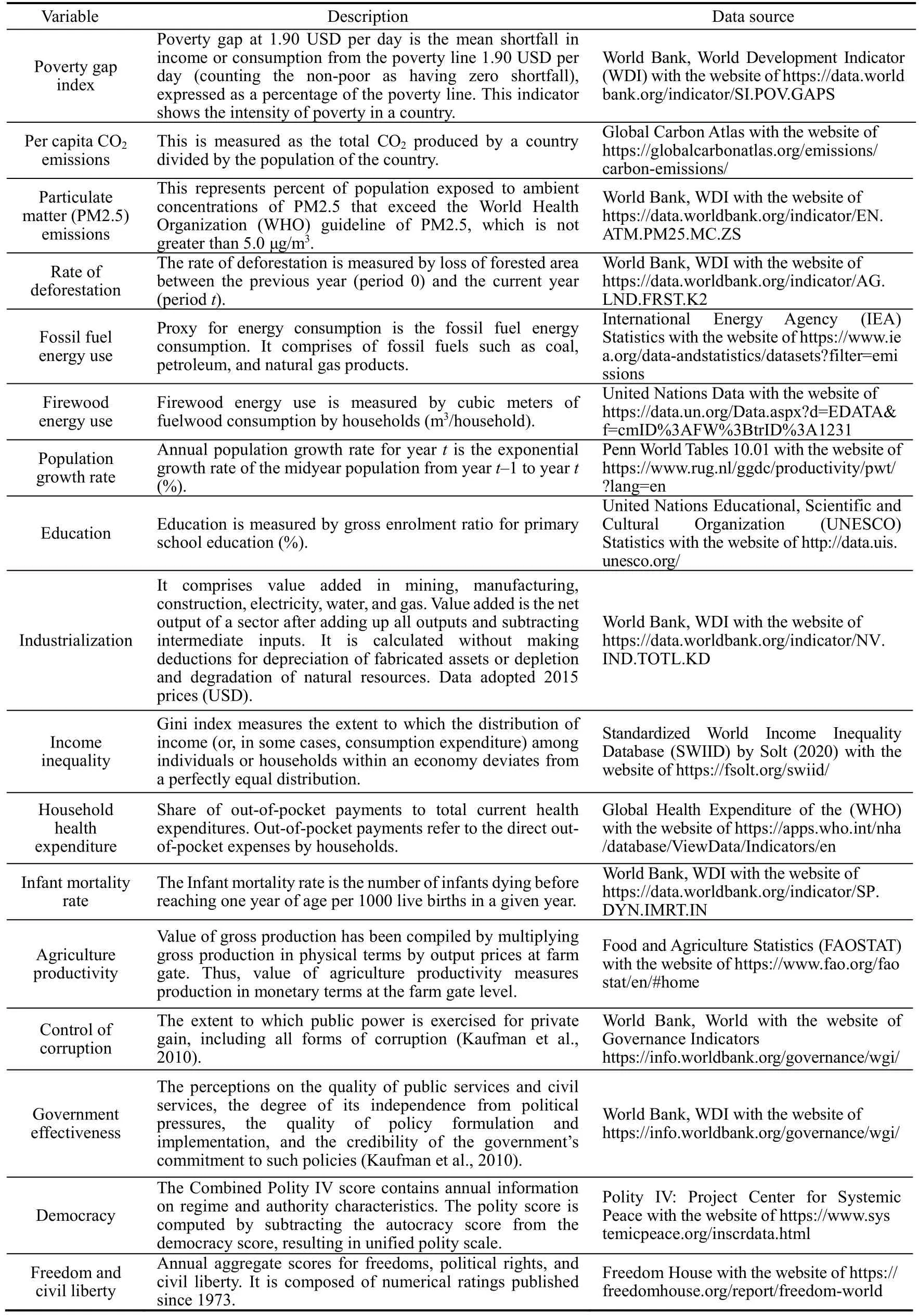

Among the socio-economic conditioning factors, we followed Ghanem (2018) to use the annual population growth rate as an indicator of population growth.We followed Masron and Subramaniam (2018) to use the school enrollment ratio obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDIs) as a proxy for education.We also included industrialization following.For income inequality, we followed Grunewald et al.(2017) and Yang et al.(2020) to use the Gini coefficient.Further, for institutional quality variables, we followed Ssekibaala et al.(2021) to use governance, corruption, freedom and civil liberty, and democracy as institutional quality variables.The description of all variables and their sources is shown in Table 1.

Table 1Definition of the variables relating to poverty-environmental degradation nexus.

3.3.Methods of estimation

Equations 7 and 8 have two fundamental econometric problems that make using these traditional approaches to estimate panel data models inadequate, such as the fixed effects (FE), random effects (RE), and the pooled ordinary least squares (POLS) approach.First, there may be a correlation between the lagged dependent variable and the unobserved country-specific effects (Amuakwa-Mensah and Adom, 2017).Second, most panel systems are usually affected by the endogeneity problem.These problems can be partially addressed through heteroskedasticity-consistent or robust standard errors.When facing heteroskedasticity, the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation procedures introduced by Hansen (1982) and Holtz-Eakin et al.(1988) provide more consistent estimates.Besides,with panel data, it is paramount to specify the correct methodology based on the data characteristics.For example,our data have a smallNand a largeT; hence, the GMM is the best method for our data.

According to Roodman (2009), the ‘difference GMM’ approach by Arellano and Bond (1991) transforms all regressors by differencing and then applies the GMM.However, the difference GMM approach suffers some limitations, including the fact that it is asymptotically weak; therefore, the accuracy of instruments causes considerable bias in finite samples.Furthermore, according to Blundell and Bond (1998), some time series are typically persistent.Therefore, in conditions when the time (T) is small, the lag of the dependent variable may exhibit persistence; hence, the lag of the levels of these variables will then become weaker instruments for the difference GMM approach.To correct the shortcomings, Roodman (2009) suggested using the ‘system GMM’ estimator developed by Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998).The system GMM derives two equations:the first is estimated in first differences, and the second in levels.Due to the high persistence in the series, the weights specified to the level estimators increase in the prevalence of weak instruments.Therefore, the first stage of the system GMM assumes independent and homoskedastic error terms, whereas the second stage allows the system to use the first step’s residuals to build consistent variances and covariance matrices.The system GMM uses the Windmeijercorrected standard errors to cater to heteroskedasticity (Windmeijer, 2005).Besides, we followed Labra-Lillo and Torrecillas (2018) to perform diagnostic tests such as the Arellano-Bond tests for first and second-order autocorrelation AR (1) and AR (2), as well as the HansenJ-test for the over-identification of instruments and the validity of instruments.

4.Empirical results, findings, and discussions

4.1.Descriptive statistics

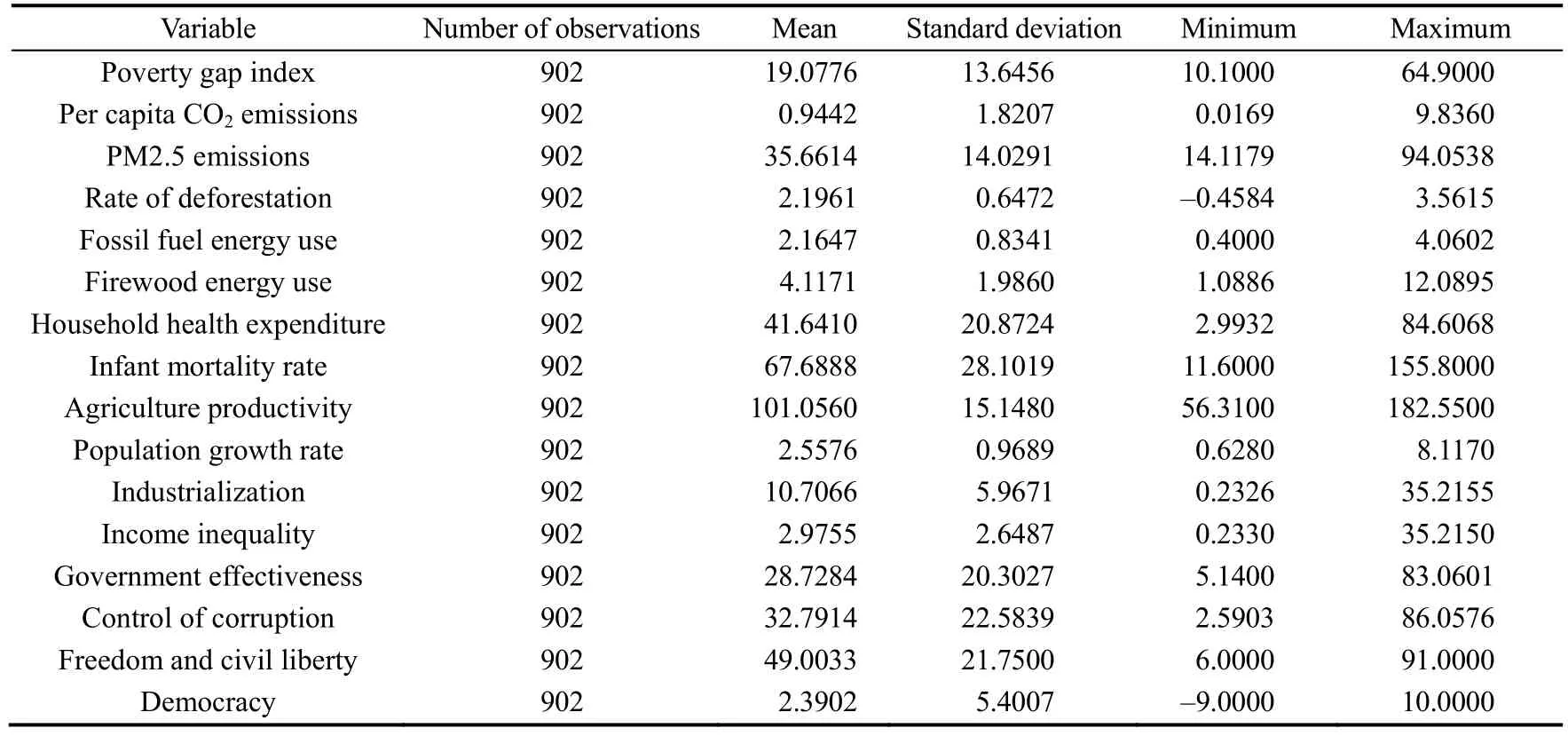

From the descriptive statistics, each variable has 902 observations (Table 2).Besides, the values of the standard deviation for per capita CO2emissions and democracy are larger than the mean values, and this may suggest that the data for the above variables are more spread out.However, the standard deviations for other variables are lower than the mean, which may indicate that the data points are clustered closer to the mean value and do not deviate far away from the mean.For example, from the descriptive statistics, the mean value for poverty gap index is 19.0776.We expected it to be in that range because, according to World Bank (2020b) data, the average value of the poverty gap index in SSA at 1.90 USD per day poverty line was 27.9000 in 1996 and 15.6000 in 2019.So, it falls in the range.However, this is very high compared to the world average, which was 9.9000 in 1996 and declined to 2.9000 in 2017(World Bank, 2020b).Therefore, whereas the minimum value at 10.1000 may be to some extent acceptable, the maximum value for poverty gap index at 64.9000 is utterly ridiculous and very high compared to the regional average.

Table 2Summary statistics of the variables used in this study.

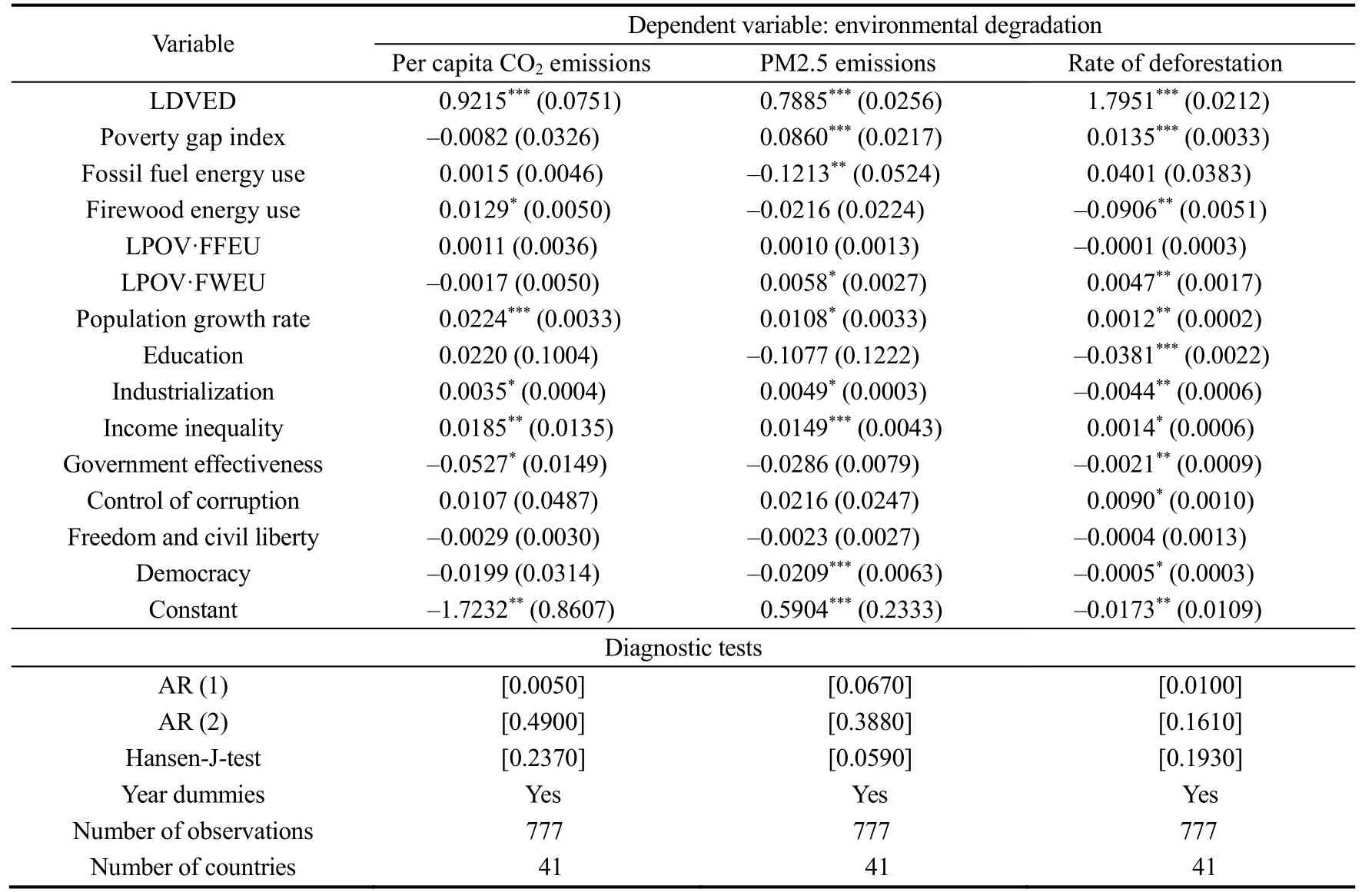

4.2.Hypothesis H1: poverty causes environmental degradation

We estimated Equation 7 for this hypothesis with environmental degradation (CO2emissions, PM2.5 emissions,and deforestation) as the dependent variables using the two-step system GMM estimator.The results for the postestimation diagnostic tests are shown in Table 3, for the AR (2) tests, we followed the null hypothesis rejection criteria provided by Labra-Lillo and Torrecillas (2018).It confirms that for all models, if theProb>Zvalues are higher than 0.050, then there is no serial correlation in the residuals.We also used the HansenJ-test for over-identification and to validate the number of instruments.The results showed that all theProb>Zvalues are significantly higher than 0.050,hence the study fails to reject the null hypothesis.As such, all our models do not suffer over-identification issues, and all the instruments are valid.Therefore, the estimated two-step system GMM is robust.

Table 3Results of the hypothesis H1 that poverty causes environmental degradation in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

From the findings shown in Table 3, we can suggest that poverty has a positive and significant relationship with PM2.5 emissions and deforestation.Hence, as poverty increases in SSA, PM2.5 emissions and deforestation will also increase.Therefore, we can conclude that poverty is a cause of environmental degradation (PM2.5 emissions and deforestation) in SSA.The finding on the case of PM2.5 emissions agrees with Koçak and Celik (2021), who examined the case of PM2.5 emissions in SSA and found that an increase in poverty will lead to further PM2.5 emissions.Besides, other studies, such as Azizi and Farzam (2022) and Ehigiamusoe et al.(2022), also showed that environmental degradation will increase with increased poverty, especially in low-income countries such as those in SSA.For the case of deforestation, our findings hold similarities with the conclusions by Barbier and Hochard (2016,2018a, 2019) but are contrary to Meher (2023), who found no empirical evidence that links poverty to causing forest degradation in poor communities of India.In addition, we found that poverty has no significant relationship with CO2emissions in SSA, which is contrary to the findings revealed by Masron and Subramaniam (2018), Baloch et al.(2020b), and Rakshit et al.(2023).

Furthermore, we hypothesized that poor people are forced to act in ways that may lead to environmental degradation.Therefore, when we interacted poverty with firewood energy use, the coefficient for LPOV·FWEU is positive and statistically significant with PM2.5 emissions and deforestation.Hence, increased firewood energy use due to increased poverty will also lead to increased PM2.5 atmospheric emissions and deforestation.This is similar with the findings by Sola et al.(2017), who suggested that poor people’s options always force them to mainly use fuelwood energy for cooking and other household uses.However, fuelwood produces dangerous carbon gases and particulate matter.In addition, continuous use of fuelwood due to poverty causes deforestation (Meher, 2023), leading to environmental degradation.

Among the socio-economic factors that act as control variables in our model, the findings shown in Table 3 suggest that population growth rate positively impacts the three indicators of environmental degradation.Therefore, an increase in population will also lead to a rise in environmental degradation in the region.Our findings provide empirical justification for the hypothesis set by Anees (2010), who used theoretical interlinkages amongst the population, poverty, and environment to hypothesize that the ecosystem and natural resources are limited as the population increases over the limit.Hence, it can be found that it is a challenge to support the increase in population without damaging the natural environment.For deforestation, the finding is similar with those by Jha and Bawa(2006), who suggested that the deforestation rate may increase as population grows.We found that education enrollment has a negative relationship with deforestation, which means that deforestation in SSA reduces as education enrollment increases.This means that deforestation will fall as more people in SSA attain an education.It is important to note that through education, citizens in SSA can be taught how to prevent and stop activities that lead to deforestation.Besides, education also helps create responsible citizens who usually demand better environmental quality (Azizi and Farzam, 2022).In addition, most schools in SSA need to teach the importance of forest conservation.Hence, improving education reduces pressure on forests in SSA.Besides, we found industrialization positively correlated with CO2and PM2.5 emissions.Therefore, CO2and PM2.5 emissions will also increase as industrialization increases.The findings on industrialization are consistent with Lin et al.(2015) and Okereke et al.(2019), who suggested that environmentally friend industrialization policies are essential in reducing carbon emissions.

Further, the findings also suggest that industrialization has a negative relationship with deforestation, which means that the rate of deforestation in SSA reduces as manufacturing increases, because industrialization reduces the poor people’s dependence on natural forests and provides alternative employment to poor people, thereby shifting labor resources away from agriculture, it can be considered a contributor to deforestation in SSA.Finally, for income inequality, the findings suggest that income inequality has a positive relationship with all three indicators of environmental degradation used.Hence, environmental degradation in SSA will increase with income inequality,consistent with Ota (2017) and Yang et al.(2020).

On institutional quality, our findings suggest that governance has a negative relationship with both CO2emissions and deforestation.As governance in SSA improves, there is a fall in both CO2emissions and the deforestation rate in the region.These findings are partially supported by Asongu and Odhiambo (2020).We also found that corruption has a positive relationship with deforestation, which means that as corruption in SSA increases, there is an increase in the region’s deforestation rate.Finally, we did not find a significant relationship between environmental degradation and freedom and civil liberty.However, our findings suggest that democracy negatively affects both PM2.5 emissions and deforestation, which means that any improvements in democracy in SSA will cause a reduction in both PM2.5 emissions and deforestation.

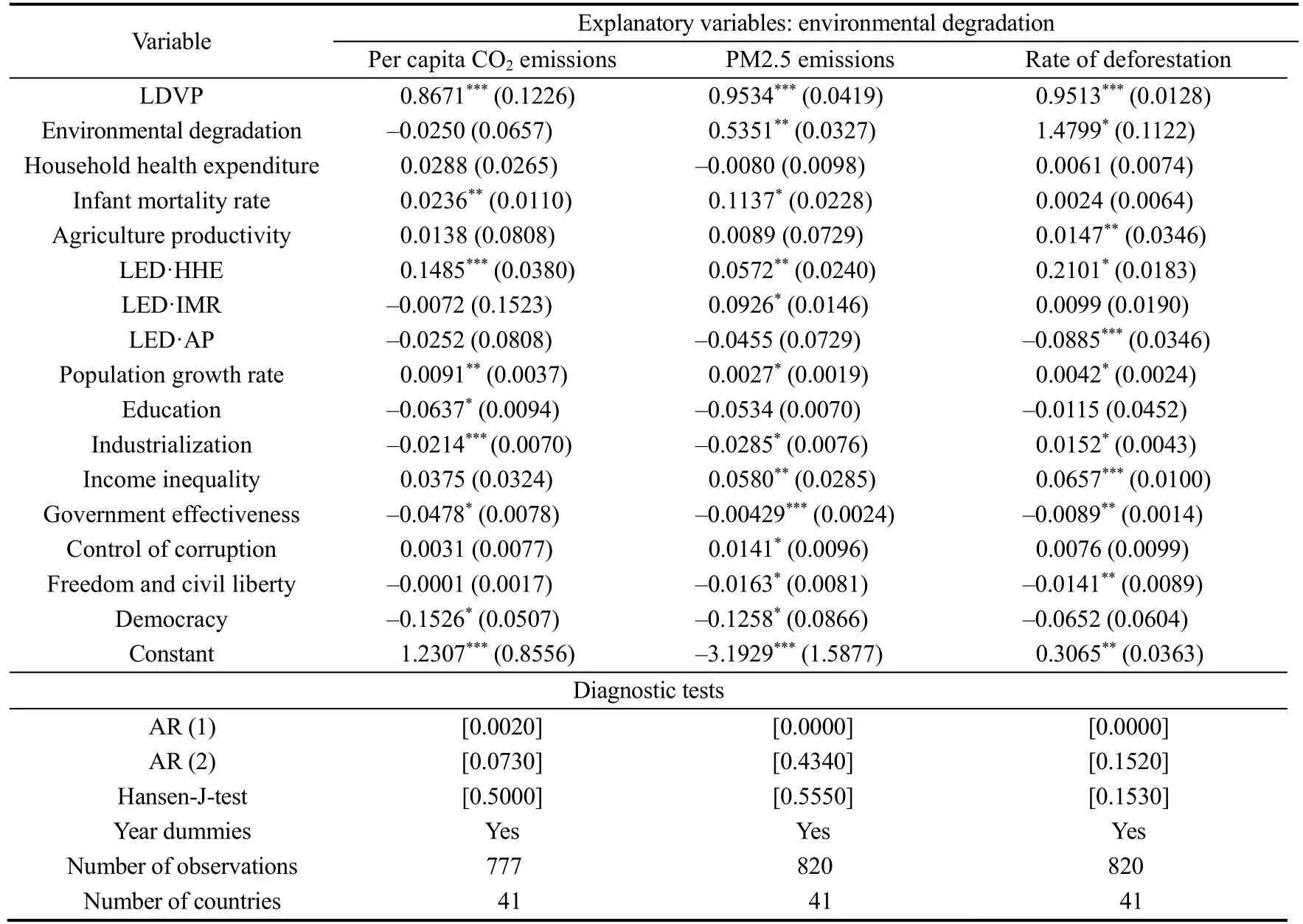

4.3.Hypothesis H2: environmental degradation leads to poverty

For this hypothesis, we estimated Equation 8 with poverty as the dependent variable while environmental degradation (CO2emissions, PM2.5 emissions, and deforestation) as the explanatory variables.We also used the twostep system GMM estimation technique, and the results are presented in Table 4.CO2emissions, PM2.5 emissions,and deforestation are used as indicators for environmental degradation, respectively.

Table 4Results of hypothesis H2 that environmental degradation causes poverty in SSA.

The results indicated in Table 4 show that when PM2.5 emissions and deforestation are used as indicators for environmental degradation, the coefficients for environmental degradation are positive and statistically significant.The positive relationship suggests that poverty increases when both PM2.5 and deforestation increase.From this, we can conclude that environmental degradation causes poverty in SSA, and we can conclude that environmental degradation worsens poverty levels in SSA.Further, in most Sub-Saharan African countries, people turn to natural resources and the natural environment for their survival in the form of food, energy functions, raw materials for production, and agriculture(Baloch et al., 2020a), environmental degradation can cause deterioration of the natural resources.As a result, their productivity starts to fall, ultimately forcing several people into poverty (Barbier and Hochard, 2018a, 2019).Therefore,most poor people in SSA will likely descend into further poverty because of environmental degradation.In addition, they are most likely to face the complexities of hunger, diseases, and the unawareness of each day of their life, which are characteristics of poverty (Broad, 1994).However, the coefficient for environmental degradation is not statistically significant when CO2emission is used; hence we cannot establish the impact of CO2emissions on poverty in SSA.

Further, we also examined the endogenous cause of poverty.In all columns, the coefficients for the interaction term LED·HHE are positive and statistically significant, from which we can conclude that environmental degradation leads to an increase in poverty through an increase in household expenditure on health.Besides, the coefficient for LED·IMR is positive and statistically significant only when PM2.5 emission is used as an environmental degradation indicator,suggesting that an increase in PM2.5 emissions will increase household poverty through its positive effect on infant mortality.Furthermore, it is essential to note that child labour is integral in generating household income in most parts of SSA.Therefore, infant mortality robs households in SSA of a considerable amount of “child labour force”, denying a substantial amount of household income that the child laborers would generate.Finally, LED·AP is negative and statistically significant when deforestation is used as a proxy for environmental degradation.From this, we can conclude that an increase in deforestation will lead to a rise in poverty by reducing agricultural productivity.Therefore, because of the vital role of forests, cutting them down will most definitely negatively impact agriculture productivity, exacerbating SSA’s poverty levels.Similar arguments are made by Fulginiti et al.(2004) and Bjornlund et al.(2020) on why agriculture productivity in SSA is still low.

Among the control variables, the coefficient for education is negative and statistically significant when CO2emission is used as an indicator of environmental degradation, which suggests that education attainment reduces poverty in SSA.It means that as more people become educated, it is easier for educated people to get jobs and get out of poverty.Furthermore, we can also conclude that industrialization has a negative relationship with poverty, suggesting that poverty in SSA declines as industrialization increases.According to Prince et al.(2017), industrialization creates more employment for poor people, thereby getting them out of poverty.We also found income inequality to have a positive relationship with poverty when PM2.5 emissions and deforestation as indicators of environmental degradation, which means that poverty in SSA increases with income inequality, as suggested by Baloch et al.(2020b).

Further, we found a positive relationship between population growth and poverty.Therefore, SSA’s high population growth rate is also associated with increased poverty, consistent with Maier (2015) and Barbier and Hochard (2018b).Further, from the findings in Table 4, we can also conclude that if governance, freedom and civil liberty, and democracy in SSA are improved, poverty will be reduced.However, high corruption will lead to increased poverty in the region.Finally, our findings on institutional quality and poverty are consistent with Rai (2019) and Baloch et al.(2020b), which suggest that institutions are essential in moderating the poverty-environmental degradation nexus in SSA.

In general, we found that poverty causes environmental degradation (PM2.5 emissions and deforestation) and environmental degradation (PM2.5 emissions and deforestation) causes poverty (Tables 3 and 4).Therefore, we can conclude that the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation (PM2.5 emissions and deforestation)follows a vicious cycle where both poverty and environmental degradation are a cause and a consequence of each other by validating hypotheses H1 and H2.However, one shortcoming of our findings is that we cannot discover which causes each other first.Furthermore, we showed that poverty-environmental degradation nexus in SSA is also influenced by several other exogenous and endogenous conditioning factors, which altogether determine the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation.

5.Conclusions and recommendations

This study provides empirical evidence on the poverty-environmental degradation nexus in SSA using data from 41 countries in SSA from 1996 to 2019.The findings also confirmed the validity of the vicious cycle relationship between poverty and environmental degradation (PM2.5 emission and deforestation) but not for CO2emissions.In addition, our results showed that exogenous conditioning factors such as population growth rate, education,industrialization, and income inequality, as well as governance effectiveness, control of corruption, freedom and civil liberty, and democracy, influence both poverty and environmental degradation to determine the nexus.We also showed that endogenous factors such as fossil fuel energy use, firewood energy use, household health expenditure,infant mortality rate, and agriculture productivity affect the nexus between poverty and environmental degradation.

The findings on the relationship between poverty and environmental degradation in SSA are a testament that poverty remains a big issue in SSA.With approximately half of the SSA’s population categorized as poor,policymakers need to understand that poverty reduction policies should not squarely focus on improving the livelihoods of people experiencing poverty but also take adequate steps and understand the environmental implication of such poverty reduction strategies.Moreover, such policies must be able to achieve both poverty reduction and environmental protection simultaneously.Whereas this may seem complicated to bundle poverty alleviation measures and environmental awareness programs targeting the poor and emphasize environmentally friend investments for poverty alleviation are possible policy alternatives that can work hand in hand.Otherwise, if efforts to reduce poverty end up leading to environmental degradation (PM2.5 emissions and deforestation), this may also worsen poverty conditions in SSA rather than solve poverty itself, thereby leading to a poverty-environmental degradation trap.

Our findings reveal that the relationship between poverty status and environmentally degrading activities is specific to the poor.This implies that low-income people may often engage in environmentally degrading activities due to limited options.With approximately half of the population of SSA falling under some category of poor, policymakers need to imagine how much environmental damage it can cause and devise policies for a possible trade-off between poverty eradication and environmental degradation.

Therefore, SSA offers new opportunities for decreasing marginality using agricultural expansion and productivity growth through sustainable solutions that target agricultural technology, research, and development, focusing on identifying traits on crops and livestock that are resilient to SSA’s environmental conditions.This will also address SSA’s constraints in agricultural productivity, lessen marginality, and contribute to widespread poverty reduction without causing unnecessary environmental degradation.

This study contributes to the current literature on the nexus between poverty and environmental degradation in SSA in a way that very few studies examine the nexus considering three environmental degradation indicators (CO2emissions, PM2.5 emissions, and deforestation) in the region.However, we also acknowledged that this study does not have reliable data for water pollution indicators such as dissolved oxygen and biochemical oxygen demand, a literature gap that may be filled by future studies when such data are made publicly available.

Authorship contribution statement

Sadat Daaki SSEKIBAALA: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing - original draft, and writing - review & editing; Twaha Ahmed KASULE: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis,methodology, and writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

杂志排行

区域可持续发展(英文)的其它文章

- Urban flood risk assessment under rapid urbanization in Zhengzhou City, China

- Research on the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity among the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation countries

- Human-wildlife conflict: A bibliometric analysis during 1991-2023

- Expert elicitations of smallholder agroforestry practices in Seychelles: A SWOT-AHP analysis

- Environmental complaint insights through text mining based on the driver, pressure, state, impact, and response (DPSIR)framework: Evidence from an Italian environmental agency

- Geotechnical and GIS-based environmental factors and vulnerability studies of the Okemesi landslide, Nigeria