Prognostic significance of preoperative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in patients with signet ring gastric cancer

2023-10-21HeLiLiuXiangFengMiMiTangHaiYanZhouHuanPengJieGeTingLiu

He-Li Liu, Xiang Feng, Mi-Mi Tang, Hai-Yan Zhou, Huan Peng, Jie Ge, Ting Liu

Abstract

Key Words: Gastric cancer; Signet ring cell carcinoma; Inflammation indexes; Coagulation indexes; Prognosis.

INTRODUCTION

Signet ring gastric cancer is a type of stomach cancer that is characterized by presence of cells filled with mucus, which push the nucleus to one side of the cell, giving it a ring-like appearance. This type of cancer is highly invasive, progresses rapidly, and has a high degree of malignancy. Although the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased in recent decades,cases of signet-ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) are increasingly being reported. Studies have demonstrated that SRCC accounts for 35 % to 45 % of all cases of gastric adenocarcinoma[1], and its incidence increased by tenfold from 1970 to 2000[2].

Currently, the prognosis of SRCC is not well understood. Given that SRCC is prone to lymph node and peritoneal metastasis, less responsive to chemotherapy, and most patients are diagnosed at an advanced cancer stage, patients with SRCC have a poor prognosis[2].

The occurrence and development of tumors are driven by several factors including inflammatory immune response of the host[3]. Numerous studies have explored the relationship between different inflammatory markers, chemotherapeutic effects, and prognosis in gastric cancer. Among the most easily available inflammatory markers obtained from the whole blood cell count are lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR)[4], neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)[5], platelet-tolymphocyte ratio (PLR)[6], and systemic immune inflammation (SII)[7]. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI), a simple and easy detection index, has been widely used in clinical practice and shown to be associated with the prognosis of malignant gastric tumors[8,9]. Moreover, the development of tumors is accompanied by changes in the blood coagulation dynamics of the host[10]. Coagulation factor levels, such as platelet count, international standard ratio, fibrin degradation products, fibrinogen, and D-dimer levels, have been associated with tumor stage, metastasis, chemotherapeutic effect,and prognosis of patients with solid tumors[11,12]. Although many scientists have explored the relationship between various indicators and chemotherapy response and prognosis of gastric cancer, few studies have explored the prognostic value of these indicators in SRCC.

Against this background, we explored the relationship between the common inflammatory indicators, nutritional indicators, coagulation indicators and the prognosis of SRCC to identify prognostic predictors of SRCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The retrospective study included 212 patients with gastric cancer admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology at Xiangya Hospital of Central South University from January 2012 to December 2016. To be included in the study, patients had to meet the following criteria: (1) Postoperative pathology revealed SRCC components greater than 10%; (2) Accepted to undergo radical gastrectomy; and (3) With complete clinical and follow-up data. Moreover, the exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Preoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and other anti-tumor treatments that may affect the patient's blood routine, liver and kidney function, and coagulation routine; (2) Preoperative examination indicated the presence of distant metastases such as liver, lung, and bone metastases; (3) Intraoperative detection of metastasis; (4) Comorbidity hematological diseases and other systemic malignancies; (5) Combined with severe infections, liver disease, kidney disease, and autoimmune diseases; (6) Emergency surgery due to perforation and bleeding of gastric cancer; and (7) Gastric stump cancer. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University.

Measurement of variables

Patient-related results, including demographic data, clinic characteristics, and biochemical test results such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), LMR [= lymphocyte count (× 109/L)/monocyte count (× 109/L)], NLR [= Neutrophil count (× 109/L)/Lymphocyte count (× 109/L)], PLR [= platelet count (× 109/L)/Lymphocyte coun (× 109/L)], SII [= Neutrophil count (×109/L) × Platelet count (× 109/L)/Lymphocyte count (× 109/L)][13], coagulation index [activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrinogen degradation product (FDP), fibrinogen (FIB), prothrombin time (PT), thrombin time (TT), and international normalized ratio (INR)] were obtained from the medical database of the hospital. Additionally, albumin(ALB), globulin (GLB), albumin to globulin ratio [AGR = serum albumin (g/L)/serum globulin (g/L)], and prognostic nutritional index [PNI = 5 × Lymphocyte count (× 109/L)+serum albumin (g/L)][14] were obtained through peripheral complete blood count and blood biochemistry before the surgery. Cut-off values for each variable were obtained from the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the data which did not fit the normal distribution was represented by M (P25, P75) and analyzed using the Mann-WhitneyUtest. Single factor analysis was performed using the independent-samplet-test for normally distributed data, and the counts were presented as percentages (%). The prognostic value of inflammation,blood coagulation and other indicators was evaluated using ROC curves, and the optimal cut-off point of patient survival was determined. The patients were then divided into high and low groups based on the medium levels of the above indicators. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the Log-rank tests were used to compare survival rates between the high and low-risk groups. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted to identify independent predictors of the prognosis of gastric cancer with SRCC by including indicators that significantly affected the survival status. Statistical significance was set atP< 0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline data and pathological characteristics

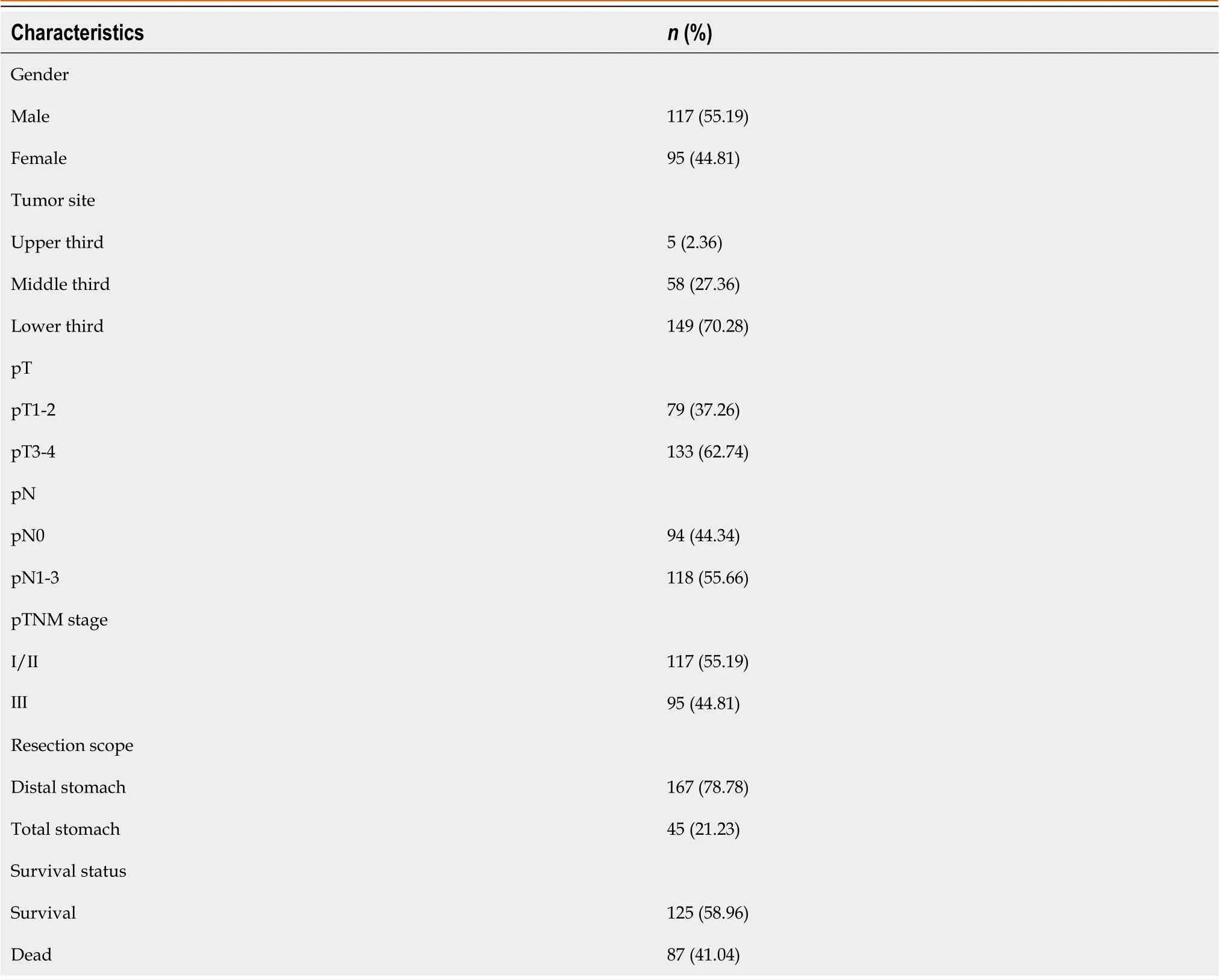

The study included 212 patients with SRCC, of whom 87 patients (41.04 %) died, and 125 patients (58.96 %) survived for the 5-year follow-up period. The mean age of the patients was 51.42 ± 11.27 years, 117 were males (55.19 %), and 95 were females (44.81 %). The tumor location was in the upper, middle and lower third of the stomach in 5 (2.36 %), 58 (27.36 %)and 149 (70.28 %) cases, respectively. Distal gastrectomy was performed in 167 (78.78 %) cases, while total gastrectomy was performed in 45 (21.22 %) cases. The tumor infiltration depth was pT1 or pT2 in 79 cases (37.26 %) and pT3 or pT4 in 133 cases (62.74 %). Lymph node metastasis was found in 118 (55.66 %) cases with pN1, pN2 or pN3, while 94 (44.34 %)cases were classified as N0. The pTNM stage was I or II in 117 cases (55.19 %) and III in 95 (44.81 %) cases (Table 1).

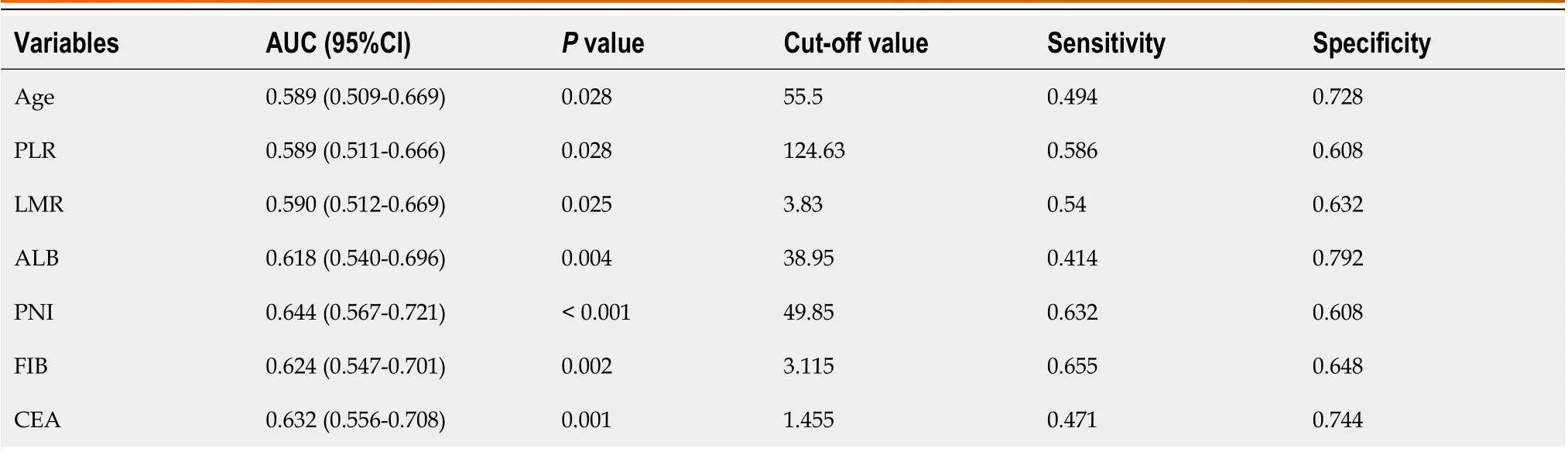

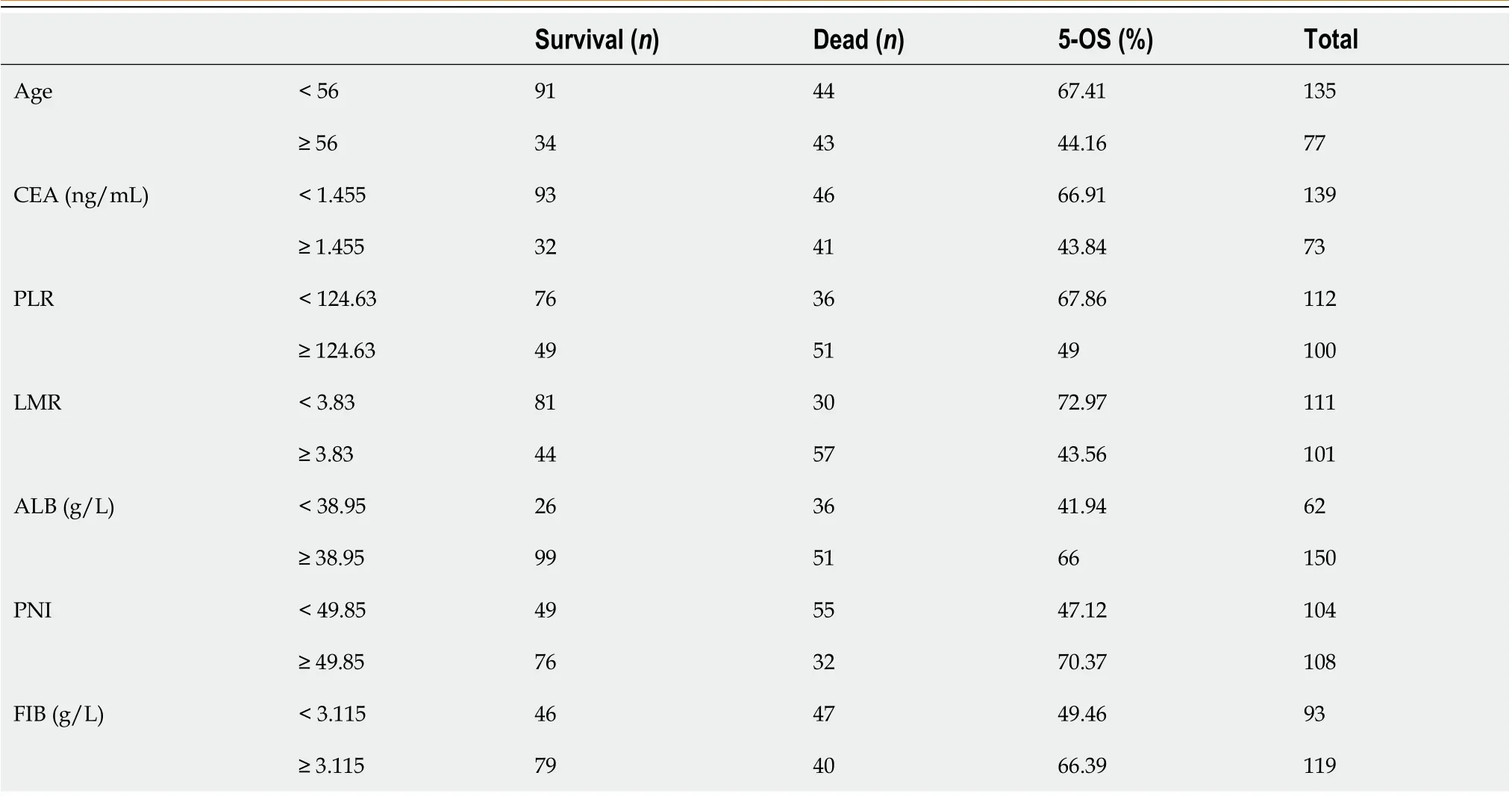

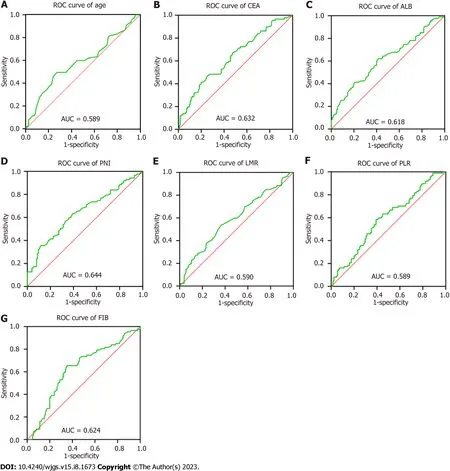

ROC analysis of predictors

Table 2 shows the cut-off value and area under the curve (AUC) for each index, and Figure 1 shows the ROC curves(AUC, 95%CI) of the predictors, including age, CEA, PLR, LMR, ALB, PNI and FIB. Overall, the results indicate good predictive values of CEA (0.632, 0.556-0.708), LMR (0.590, 0.512-0.669), ALB (0.618, 0.540-0.696), PNI (0.644, 0.567-0.721),and FIB (0.624, 0.547-0.701).

Single factor analysis for prognostic factors

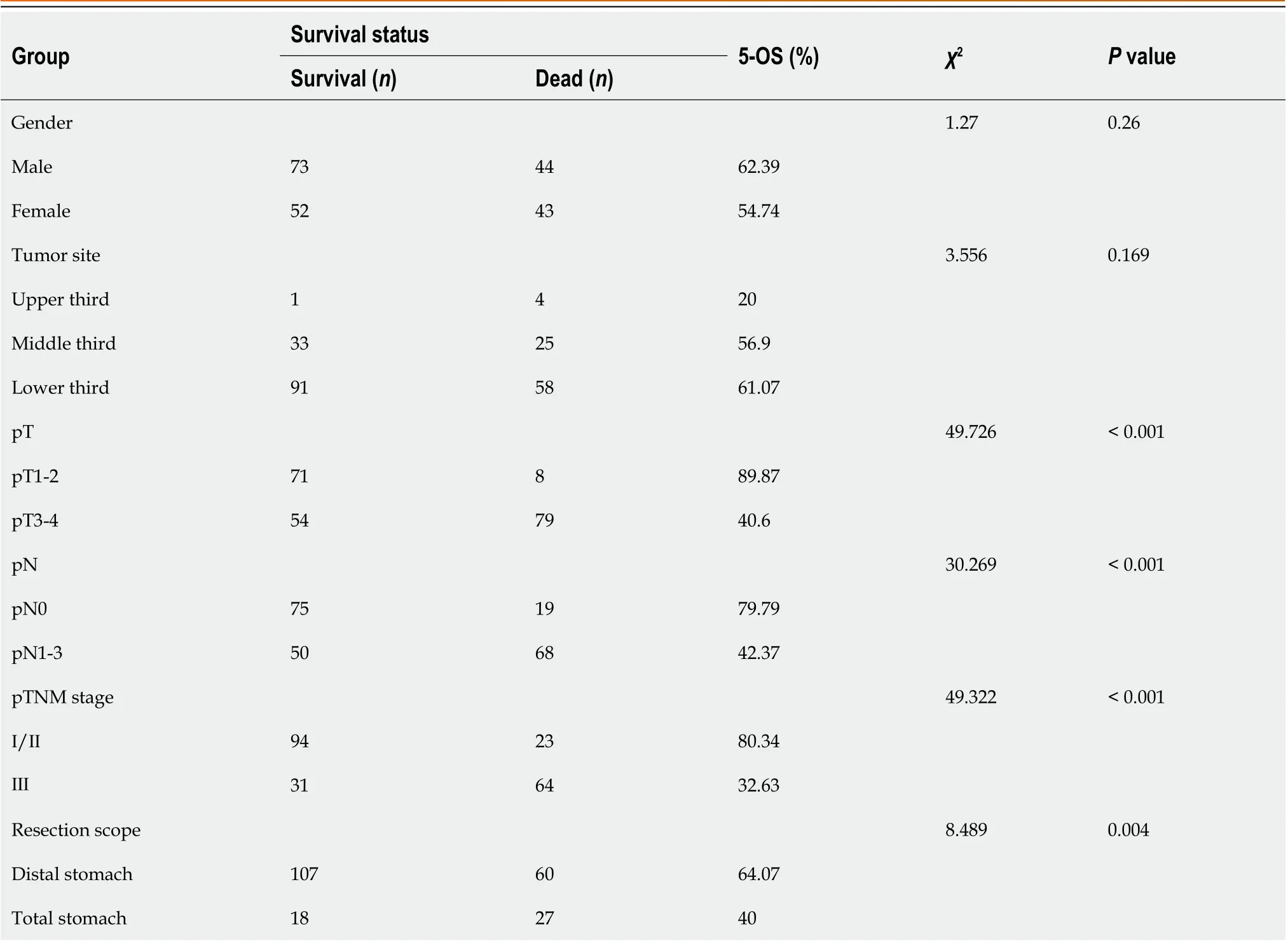

Table 3 displays the results of the pathological features and the 5-year survival rate of the patients. The analysis revealed that depth of tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, pTNM stage and resection range were associated with the survival rate, while gender and tumor location showed no correlation.

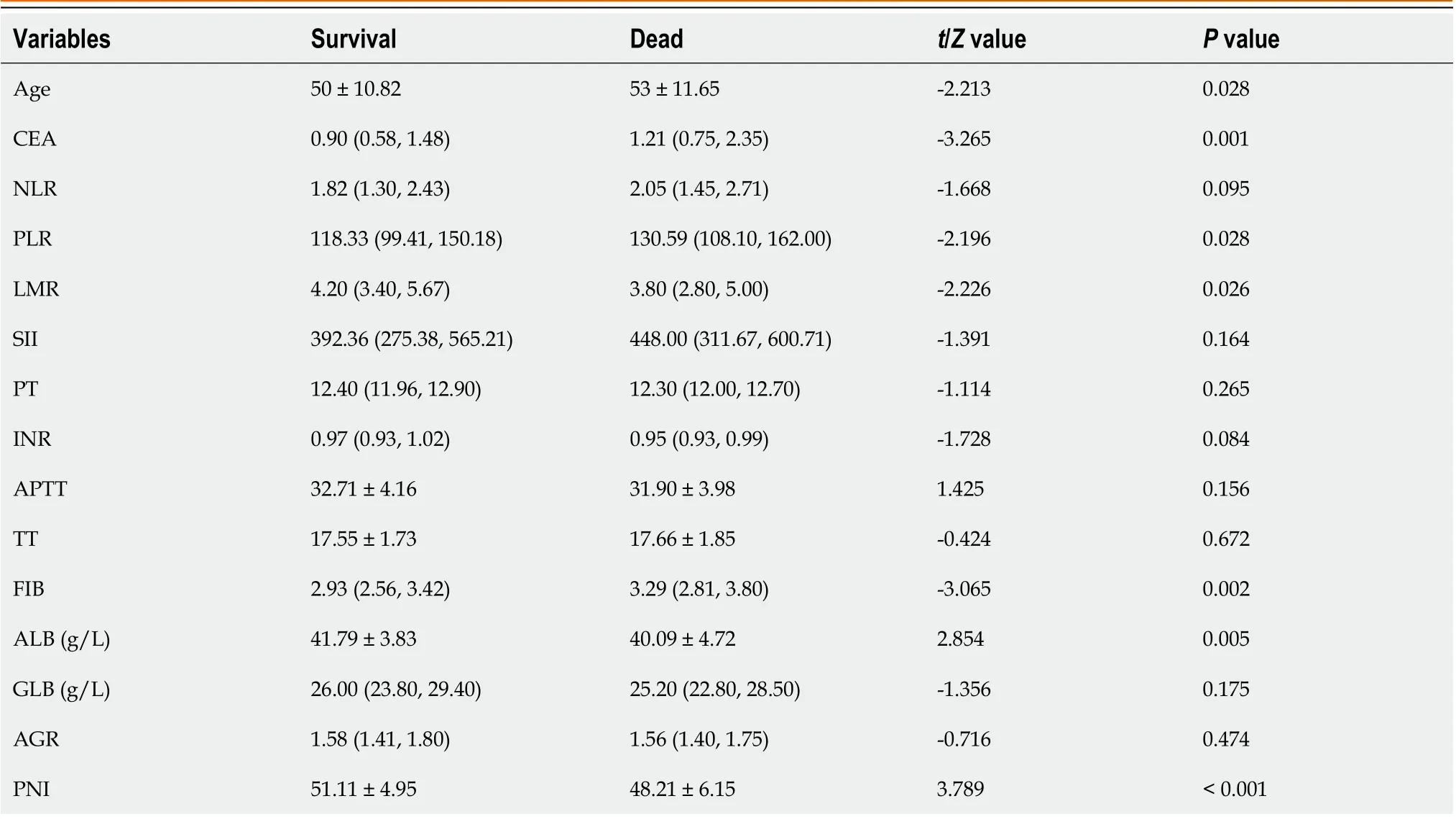

As shown in Table 4, firstly, the single factor analysis demonstrated that younger patients had a better survival rate compared with older patients. The survival rate was also significantly better in the lower CEA level group compared with the higher CEA level group. In addition, SRCC patients in the higher PLR value had poorer survival rates than those inthe lower PLR value group, while SRCC patients in the higher LMR value group had a better survival rate than those in the lower LMR value group. Finally, the survival rate of patients with lower FIB was significantly better in those with higher FIB, whereas patients with lower ALB had a significantly lower survival rate compared with higher ALB group.

Table 1 Baseline data and pathological features of the study participants

Table 2 Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis results of predictors

Grouping of predictors

The predictors, including age, CEA, ALB, PNI, LMR, PLR, and FIB, were grouped as shown in Table 5.

Table 3 Relationship between baseline data, pathological features and 5-year survival rate

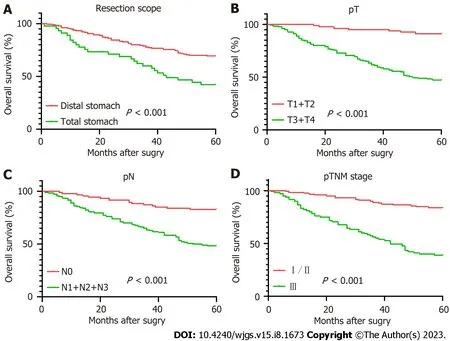

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves are shown in Figure 2. The Log-rank test indicated no significant difference in survival rate between the low PLR group and the high PLR group (P= 0.147). In contrast, significant differences were observed in survival rate between different resection groups (P< 0.001), depth of invasion (P< 0.001), lymph node metastasis (P<0.001), pTNM stage (P< 0.001), age (P= 0.004), LMR (P= 0.003), ALB (P= 0.008), PNI (P= 0.002) and FIB (P= 0.001).

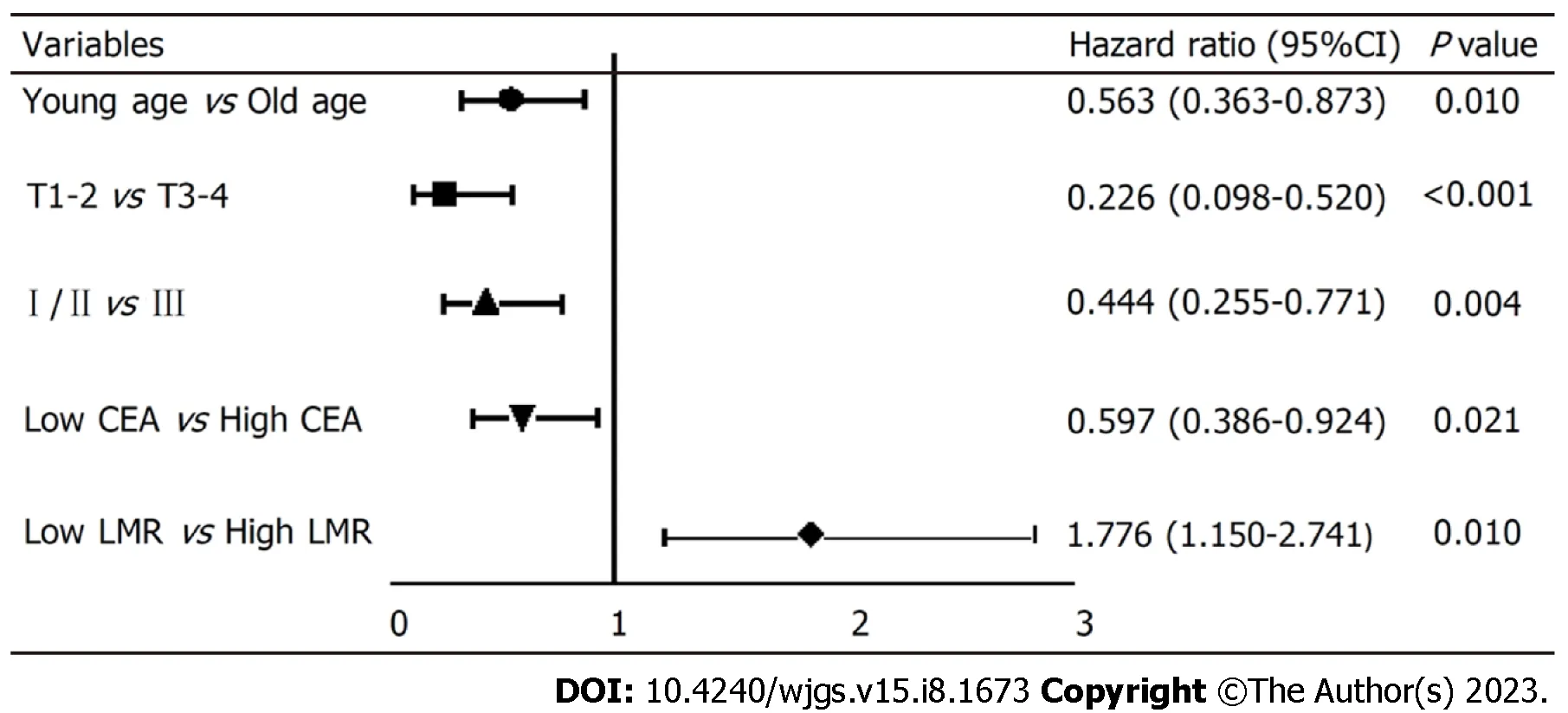

Multivariate and multiple-factor analysis

To explore the independent factors affecting the prognosis of SRCC, indicators that demonstrated statistical differences by the Log-rank test were included in a Cox proportional hazards regression model for multivariate analysis. The results(HR, 95%CI) are presented in Figure 3. The independent factors for SRCC prognosis were age (0.563, 0.363-0.873,P=0.010), depth of tumor invasion (0.226, 0.098-0.520), pTNM stage (0.444, 0.255-0.771), preoperative CEA level (0.597, 0.386-8.790), and preoperative LMR level (1.776, 1.150-2.741). Advanced age, high CEA level before surgery, low LMR level before surgery, deep tumor invasion, and late pTNM stage were all indicative of a relatively poor prognosis. Specifically,the risk of death in low LMR group before surgery was 1.776 times higher than that of the high LMR group.

DISCUSSION

Currently, surgery is the mainstay treatment for gastric cancer patients, especially those with SRCC. However, despite radical resection or adjuvant chemotherapy, the prognosis of SRCC patients, particularly those in advanced stages, is not optimistic. Therefore, it is crucial to elucidate the mechanism of tumor progression and identify independent prognostic factors to evaluate the overall condition of tumor patients and optimize diagnosis and treatment.

The correlation between inflammation and tumors was first proposed by Rudolf Virchow[14]. Research has shown that inflammation participates in tumor development[15,16]. Furthermore, inflammation can influence the prognosis of tumors by altering immune response[17,18].

Lymphocytes and monocytes play a crucial role in anti-tumor immune response[19]. The relationship between LMR and the prognosis of malignant tumors has been widely reported[20-22]. However, few studies have investigated therelationship between inflammatory markers and SRCC. Chengcheng Tonget al[23], reported that derived monocyte-tolymphocyte ratio (dMLR) could independently predict lymph node metastasis of SRCC. Zhuet al[9] reported the relationship between SII and the prognosis of SRCC, but the relationship between LMR and SRCC has not been investigated.

Table 4 Relationship between indicators and survival status

Table 5 Grouping of predictors

Figure 1 Receiver operating characteristic curves of all predictors. A: Age; B: Carcinoembryonic antigen; C: Albumin; D: Prognostic nutritional index; E:Lymphocyte to monocyte ratio; F: Platelet to lymphocyte ratio; G: Fibrinogen.

Numerous studies have shown that high levels of peripheral blood lymphocyte count and TILs are associated with a good prognosis in gastric cancer[24-26]. Liet al[27] reported that patients with smaller tumors (< 5 cm) had higher counts of peripheral blood CD4 + T cells (P= 0.003) and CD8 + T cells (P= 0.002). In addition, patients with well-differentiated gastric cancer showed higher counts of CD4 + T cells (P= 0.029).

NK cells, which possess potent anti-tumor, anti-viral and antibacterial activity, are crucial in activating and regulating adaptive immune responses. In human peripheral blood, NK cells account for approximately 3%-5% of lymphocytes[28,29]. The anti-tumor activity of NK cells is mainly determined by a group of inhibitory and activating receptors[30].Patients with gastric cancer exhibit lower expression of activating receptors such as NKG2D, NKp30, and NKp46, but higher PD-1 expression. Moreover, NK cells of patients with gastric cancer secrete lower cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α,IL-12) and impaired ability to release perforin and granzyme. Meanwhile, gastric cancer cells express little MICA/B,ULBP, and B7H6, to evade NK cell-mediated innate immunity. Gastric cancer cells can also produce cytokines such as IL-10, TGF-β, and PGE2, which recruit MDSC and Treg cells to suppress NK cell function[31]. The proportion of apoptotic NK cells in patients with gastric cancer is elevated when receiving gastrectomy[32]. Collectively, these lines of evidence show that the number and function of NK cells decrease sharply with the progression of gastric cancer[31].

Figure 2 The survival curves of all predictors. A: Resection scope; B: Infiltration depth; C: Lymph node metastasis; D: pTNM staging;

Figure 3 Survival of patients with different characteristics in Cox regression model. CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; LMR: Lymphocytes to monocytes.

Monocytes, particularly those that differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), contribute to the development of gastric cancer[33]. M1 TAMs have anti-tumor effects, while M2 TAMs promote tumor growth[34]. Under the influence of cytokines and extracellular matrix secreted by tumour cells and lymphocytes, M1 TAMs can convert into M2 TAMs. In gastric cancer, M2 TAMs are highly expressed in SRCC, mucinous adenocarcinoma and diffuse gastric cancer[35].

Our study found that the 5-year survival rate of patients with low LMR before surgery was significantly lower than that with high LMR. In summary LMR affects the prognosis of SRCC due to reduction of lymphocytes during inflammatory response and increase of tumor-associated macrophages produced by circulating monocytes. However, this study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective single-center study and no external validation was performed. In addition, studies have suggested that gastric cancer with different SRCC ratios may have varying biological characteristics, although we demonstrated a relationship between LMR and the prognosis of SRCC. Therefore, it is imperative to explore further the predictive value of various indicators in gastric cancer with different SRCC ratios.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study shows that a low preoperative LMR level indicates a poor prognosis of signet ring gastric cancer.Particularly, compared with the high LMR group, the risk of mortality in the low LMR group is 1.776.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Liu HL, Feng X contributed equally to this work; Liu HL, Feng X and Ge J designed research; Tang MM, Zhou HY and Feng X collected and analyzed clinical data; Liu T, Peng H wrote the paper.

Supported bythe Clinical Research Fund of National Geriatric Disease Clinical Medical Research Center, No. 2022LNJ22; Guangdong Yiyang Healthcare Charity Foundation, No. JZ2022014.

Institutional review board statement:The study was reviewed and approved by the Xiangya Hospital, Central South University Institutional Review Board [Approval No. Xykyll-lx-2019030510].

Informed consent statement:All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:No additional data are available.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:He-Li Liu 0000-0002-3443-6174; Xiang Feng 0000-0003-1490-6789; Mi-Mi Tang 0000-0002-1517-6637; Hai-Yan Zhou 0000-0002-2860-1858; Huan Peng 0000-0002-3073-5708; Jie Ge 0000-0002-4186-4740.

S-Editor:Ma YJ

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Zhang YL

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery的其它文章

- Is endoscopic mucosal resection-precutting superior to conventional methods for removing sessile colorectal polyps?

- Knowledge, attitude, and practice of monitoring early gastric cancer after endoscopic submucosal dissection

- Changing trends in gastric and colorectal cancer among surgical patients over 85 years old: A multicenter retrospective study, 2001-2021

- Enhanced recovery nursing and mental health education on postoperative recovery and mental health of laparoscopic liver resection

- Effects of ultrasound monitoring of gastric residual volume on feeding complications, caloric intake and prognosis of patients with severe mechanical ventilation

- Risk factors and their interactive effects on severe acute pancreatitis complicated with acute gastrointestinal injury