Cardiometabolic effects of breastfeeding on infants of diabetic mothers

2023-05-19ReemElbeltagiMohammedAlBeltagiNerminKamalSaeedAdelSalahBediwy

Reem Elbeltagi, Mohammed Al-Beltagi, Nermin Kamal Saeed, Adel Salah Bediwy

Reem Elbeltagi, Department of Medicine, Irish Royal College of Surgeon, Busaiteen 15503, Bahrain

Mohammed Al-Beltagi, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta 31511, Egypt

Mohammed Al-Beltagi, Department of Pediatrics, University Medical Center, King Abdulla Medical City, Arabian Gulf University, Manama 26671, Bahrain

Nermin Kamal Saeed, Medical Microbiology Section, Department of Pathology, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain, Manama 12, Bahrain

Nermin Kamal Saeed, Department of Microbiology, Irish Royal College of Surgeon, Bahrain, Busaiteen 15503, Bahrain

Adel Salah Bediwy, Department of Chest Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, Tanta 31527, Egypt

Adel Salah Bediwy, Department of Pulmonology, University Medical Center, King Abdulla Medical City, Arabian Gulf University, Manama 26671, Bahrain

Abstract BACKGROUND Breast milk is the best and principal nutritional source for neonates and infants. It may protect infants against many metabolic diseases, predominantly obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic and microvascular disease that affects all the body systems and all ages from intrauterine life to late adulthood. Breastfeeding protects against infant mortality and diseases, such as necrotizing enterocolitis, diarrhoea, respiratory infections, viral and bacterial infection, eczema, allergic rhinitis, asthma, food allergies, malocclusion, dental caries, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis. It also protects against obesity and insulin resistance and increases intelligence and mental development. Gestational diabetes has short and long-term impacts on infants of diabetic mothers (IDM). Breast milk composition changes in mothers with gestational diabetes.AIM To investigate the beneficial or detrimental effects of breastfeeding on the cardiometabolic health of IDM and their mothers.METHODS We performed a database search on different engines and a thorough literature review and included 121 research published in English between January 2000 and December 15, 2022, in this review.RESULTS Most of the literature agreed on the beneficial effects of breast milk for both the mother and the infant in the short and long terms. Breastfeeding protects mothers with gestational diabetes against obesity and type 2 DM. Despite some evidence of the protective effects of breastfeeding on IDM in the short and long term, the evidence is not strong enough due to the presence of many confounding factors and a lack of sufficient studies.CONCLUSION We need more comprehensive research to prove these effects. Despite many obstacles that may enface mothers with gestational diabetes to start and maintain breastfeeding, every effort should be made to encourage them to breastfeed.

Key Words: Breast milk; Breastfeeding; Gestational diabetes mellitus; Cardiometabolic effects; Infants of diabetic mothers; Obesity

INTRODUCTION

Breast milk is the best and principal nutritional source for neonates, providing them with the needed protein, fat, carbohydrate, vitamins, and minerals requirements. In addition, it provides them with different substances and bioactive agents that help protect them against infections and inflammation by contributing to a healthy microbiome, organ development, and an efficient immune system[1]. Breast milk is rich in growth factors that support the development and growth of the newborn's brain, gut, endocrine, and vascular systems[2]. Many studies suggested that breast milk protects infants against many metabolic diseases, predominantly obesity and type 2 diabetes[3]. Breast milk is continuously changing with dynamic and bioactive composition modification from colostrum to late stages of lactation. It often varies diurnally, within feeds, between different populations, and even between mothers from the same population to meet the metabolic needs of their babies[4]. The amount of breastmilk needed at one month of age is about 650 mL/d, increased to 770 mL/d at three months and 800 mL/d at six months, then dropped to 520 mL/d by one year of age. In addition, the duration and frequency of breastfeeding also change with infant development and maturation, starting with 20 to 40 min, up to six times/d, which is reduced to 10-20 min when the infant reaches three months of age. The frequency of breastfeeding decreases as the weaning starts[5].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic and microvascular disease that affects all the body systems and all ages from intrauterine life to late adulthood. DM that occurs during pregnancy could have its onset before or arise as de novo for the first-time during pregnancy (gestational DM), which could disappear or persist after delivery[6]. Impaired glucose tolerance occurs in 3%-10% of pregnancies and correlates positively with the average diabetes incidence in the general population. The risk of gestational diabetes increases with advanced maternal age, obesity, non-white ancestry, and physical inactivity[7]. Gestational diabetes has short and long-term effects on infants of diabetic mothers (IDM). Neonates have a higher risk of post-natal hypoglycemia, macrosomia, respiratory problems, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, congenital disabilities, and various metabolic and hematologic disorders. At the same time, there is an increased risk of obesity during childhood and type 2 DM in adulthood[8]. Breastfeeding is well known to have many beneficial effects on both mothers and infants. However, the breast milk of mothers with diabetes has altered composition. Therefore, it is expected to have different effects than those from non-diabetic mothers[9]. This review investigates the beneficial or detrimental effects of breastfeeding on the cardiometabolic health of IDM and their mothers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

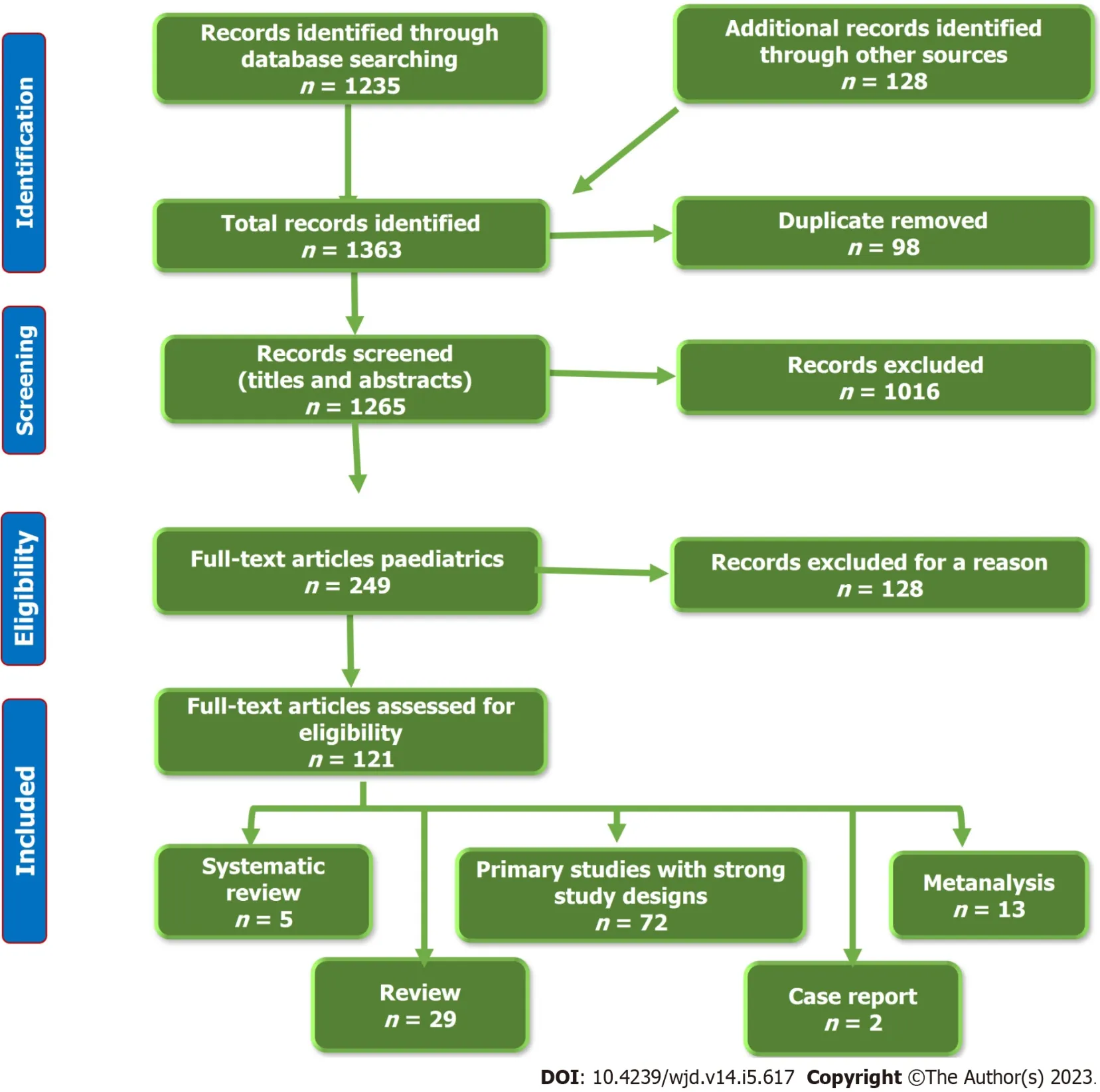

To establish an evidence-based vision of this aim, we performed a thorough literature review by searching the available electronic databases, including Cochrane Library, PubMed, PubMed Central, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, Web of Science, Library and Information Science Abstracts, Scopus, and the National Library of Medicine catalog up until December 15, 2022, using the keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Gestational Diabetes, Cardiometabolic, Breastfeeding, Breast milk. We identified 1363 articles, 98 of which were removed due to duplication. After the screening of the titles and abstract, we excluded 1016 articles. From the remaining 249 full-text articles, only 121 articles fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

We included full-text research articles (72 articles), metanalysis (13 articles), systematic reviews (5 articles), reviews (29 articles), and Case reports (2 articles). We included articles that were written in English and concerned with the effects of breastfeeding on the cardiometabolic effects in IDM. Figure 1 shows the study flow chart. Reference lists were checked, and citation searches were performed on the included studies. We also reviewed the articles that are available as abstracts only. We excluded articles with a commercial background.

Figure 1 The flow chart of the included studies.

RESULTS

Most of the literature agreed on the beneficial effects of breast milk for both the mother and the infant in the short and long terms. Breastfeeding protects mothers with gestational diabetes against obesity and type 2 DM. Despite some evidence of the protective effects of breastfeeding on IDM in the short and long term, the evidence is not strong enough due to the presence of many confounding factors and a lack of sufficient studies.

DISCUSSION

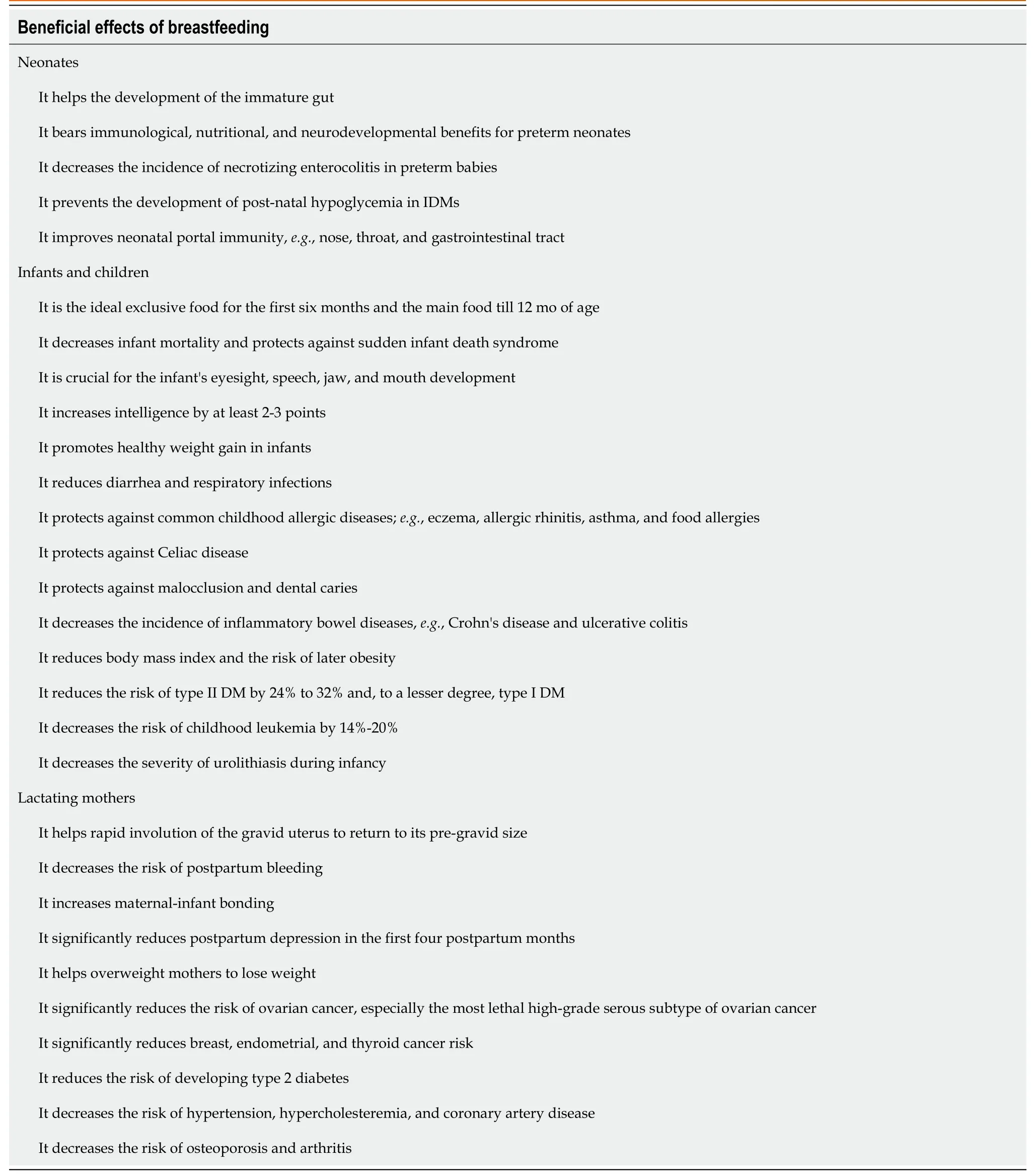

Beneficial effects of breastfeeding

Breast milk is the ideal nutrition source for the infant, especially in the first six months, as it provides the baby with everything they need in the proper proportions for the first six months of life. Its composition modifies according to the infants’ changing requirements, particularly in the first few weeks of life. Colostrum is the wonder of breastfeeding in the first post-natal days, with thick yellowish color, high protein, low sugar, and many beneficial compounds. It helps develop the baby's immature gut to be ready to receive the increasing amount of breastfeeding in the following days[1]. In addition, early breastfeeding in the delivery room may prevent the development of post-natal hypoglycemia in IDMs[10]. However, breastfeeding has low vitamin D. Breastfed babies should be supplemented with vitamin D[11]. The low iron profile in breast milk could be beneficial in decreasing the risk of bacterial growth. Iron supplementation in breastfed babies should be considered to improve brain and cognitive development, especially those born prematurely or at low birth weight [12].

Breastfeeding performs crucial effects on the programming activity during early life. Many recent meta-analyses of several studies provide strong evidence that breastfeeding benefits neonates, infants, children, and lactating mothers considerably. The degrees of these beneficial effects vary according to different settings’ background environmental and hygienic conditions[13]. According to 28 metanalyses, breastfeeding protects against infant mortality, especially in low-income settings, by 4-10 times and by 36% in high-income settings[14]. Breastfeeding also protects against many diseases, such as diarrhea by 75% and respiratory infections by 57%, particularly in young children[15]. Breast milk has plenty of antibodies that protect the baby against many viruses and bacteria, which is particularly important during the early critical months of life. Colostrum provides the baby with many different antibodies, especially immunoglobulin A, a crucial element of the baby portal immunity, protecting the nose, throat, and gastrointestinal tract[16].

Breastmilk may also give some protection against eczema, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and food allergies, but with weak evidence[17]. Even though breastfeeding protects against malocclusion and dental caries, more prolonged breastfeeding (beyond one year of age) and nocturnal breastfeeding increase dental caries by two to three folds[18]. It can decrease the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm babies. A meta-analysis by Altobelliet al[19] showed that premature infants who received both their own and donated breastmilk had a statistically significant reduced risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, possibly due to the reduced microbial contamination, its pre, and probiotic effects, and its unique immunological components. Breastfed infants are less liable to develop Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. A meta-analysis by Xuet al[20] showed that breastfeeding is associated with a reduced risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in all ethnicities, particularly among Asians. Breastfeeding has dose-dependent protection against Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, with the most potent effect when breastfeeding continues for at least one year.

Breastfeeding causes a mild reduction of body mass index (BMI) without significant differences in growth outcome. However, a meta-analysis by Giuglianiet al[21] showed a 13% reduction in the risk of later obesity. Grubeet al[22] showed that breastfeeding for longer than four months significantly reduces the risk of developing overweight and obesity than in non-breastfed babies or those with a shorter breastfeeding period. The weight-reducing effects of breastfeeding could be related to the development of specific strains of gut microbiota that could impact fat storage[23]. At the same time, breast milk contains more leptin hormone than formula milk, if present. Leptin is a vital hormone that regulates the baby’s appetite and controls fat storage[24]. Meanwhile, breastfed infants have more selfregulation of their feeding habits, especially those in on-demand feeding, which supports them in developing healthy feeding patterns[25].

Therefore, the risk of type 2 DM can be reduced by 24% to 32% and to a lesser degree with type 1 DM[26]. Meanwhile, six months or longer of breastfeeding decreases the risk of childhood leukemia by 14%-20%[27]. Breastfeeding also helps to alleviate the clinical course and the severity of urolithiasis identified during infancy. Infants who had prolonged breastfeeding are more liable for reduced size and/or the number of urinary stones. Infants receiving breastfeeding for the first six months need less treatment and have less growth impairment[28].

There is also an association between breastfeeding and increased intelligence by at least 2-3 points after adjusting for the home environment and average parental intelligence quotient (IQ). This increase may be related to the nutritional components, non-nutritional bioactive factors, maternal-infant bonding with physical intimacy, interactions, touch, and eye-to-eye contact. Infants with breastfeeding are less liable to have behavioral problems or learning difficulties than bottle-feeding infants. This breastfeeding-promoting effect on the baby’s optimal brain development during early life can have longlasting impacts on infant neurodevelopmental function[29,30]. This effect is more pronounced in preterm babies than in term infants. Belfortet al[31] showed that predominant breastfeeding in the first four weeks of life is related to a larger volume of deep nuclear gray matter volume at term equivalent age and improved IQ, working memory, academic achievement, and motor function at the age of seven in the very preterm infants. Increasing breastfeeding duration is positively correlated with enhancing cognitive development. Ribas-Fitóet al[32] observed a linear dose-response relationship between breastfeeding and cognition at the age of four in children with a history of antenatal exposure to dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) despite the risk of breastfeeding pollution with DDT. Breastfeeding protects against indoor and outdoor air pollution exposure and adverse outcomes due to the effects of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA), carotenoids, antioxidant vitamins, flavonoids, cytokines, and immunoglobins. Though breastfeeding may be polluted with many pollutants, its protective effects outweigh its potential health hazards to the infant[33] (Table 1).

Table 1 Beneficial effects of breastfeeding

Beneficial effects on lactating mothers

Breastfeeding has significant impacts on lactating mothers. It may help overweight mothers to lose weight. Numerous studies described a positive correlation between postpartum weight loss and breastfeeding, while others studied did not find a significant association. Several possible mechanisms, determinants, and metabolic pathways may play a role in this weight reduction[34]. Lactating mother burns about 20 calories/ounce of breastmilk she produces. Therefore, one day of breastfeeding may help burn up to 900 calories and more fat. Jarlenskiet al[35] showed that exclusive breastfeeding for at least three months or more has a minimal but considerable effect on postpartum weight reduction among American women. Schallaet al[36] showed that returning to a pre-pregnancy body shape is an important feature that encourages mothers to continue breastfeeding. One of the other immediate benefits that lactating mothers have with breastfeeding is the rapid involution of the gravid uterus to return to its pre-gravid size due to oxytocin release in response to the sucking of the breastfed baby, which boosts uterine contractions and lessens bleeding. In addition, oxytocin helps to increase maternalinfant bonding[37].

Breastfeeding is correlated with a significantly reduced risk of ovarian cancer in general and, in particular, for the most lethal high-grade serous subtype of ovarian cancer. This finding suggests that breastfeeding is a possibly modifiable factor that may decrease the risk of ovarian cancer regardless of the effect of pregnancy. The longer the breastfeeding duration, the more the risk is reduced[38]. A metaanalysis by Unar-Munguíaet al[39] showed that exclusive breastfeeding significantly reduces breast cancer risk compared to non-breastfeeding parous women. Breastfeeding mothers are less likely to suffer postpartum depression than mothers who do not breastfeed or discontinue it early. These effects are maintained for the first four postpartum months. Conversely, postpartum depression reduces the breastfeeding rate in a reciprocal mechanism[40].

The longer the duration of breastfeeding, the less the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in lactating women. Schwarzet al[41] showed that breastfeeding is associated with improved maternal glucose metabolism. They also showed an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in later life when the parous women lactate for less than a month after term pregnancy, regardless of the women’s BMI or physical activity. Breastfeeding also decreases the risk of hypertension, hypercholesteremia, and arthritis. In addition, breastfeeding protects mothers who breastfeed their children for five months or more in at least one pregnancy against coronary artery disease (CAD), with a 30% risk reduction later in life. Conversely, parous women who never breastfed or stopped breastfeeding early have a two-fold increased risk of CAD[42].

Mechanism of protective effects of breastfeeding

Many possible mechanisms are proposed to explain the protective effects of breastfeeding. These mechanisms include the beneficial effects of breastfeeding on the respiratory, nervous, and immune systems, which are related to breast milk's anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective, and immunomodulatory features[33]. The high cholesterol content of breast milk during infancy inversely suppresses endogenous cholesterol synthesis in adulthood by suppressing the regulation of hydroxymethyl-glutaril liver coenzyme A[43,44]. Therefore, breast milk protects against the development of hypercholesteremia, especially low-density lipoprotein cholesterol which is a significant risk factor for coronary heart diseases[45]. This cholesterol-regulating effect of breast milk can explain its protective effects against atherosclerosis, hypertension, and coronary heart diseases. The low sodium and the high LC-PUFA contents of breast milk compared to formula milk might give more protection against the future development of hypertension during childhood and adulthood[46,47]. LC-PUFA is a crucial element of the tissue membrane system, such as the coronary endothelial system, therefore reducing the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke during adulthood[48]. Breastfeeding can also reduce fasting insulin and insulin resistance in infancy, childhood, and adulthood[49,50].

Breastfeeding has a behavioral modifying effect on the infant's appetite, satiety, and feeding pattern due to its unique micro- and macro-nutrients and hormonal contents. These unique features of breastmilk explain its protective role against obesity[51,52]. Breastmilk contains leptin, which is not present in formula milk, and less protein and fat than formula milk, so breastfeeding is likely to adequately stimulate the secretion of insulin growth factor-type 1. Subsequently, it can induce adequate insulin secretion, fewer adipocytes stimulation and size, and balancing fat reserve, which eventually results in adequate weight gain and is less likely to cause overweight and obesity[51,53]. Breastmilk can also modulate the expression of obesity-predisposing genes, preventing the development of obesity and other non-communicable diseases[54]. Breastmilk has a significant regulating effect on the blood glucose level due to its high content of LC-PUFA. The LC-PUFA amount in the skeletal muscle membranes is inversely proportional to the fasting blood glucose level, insulin resistance, subsequent hyperinsulinemia, and type 2 diabetes[55,56]. The low protein content, the lower volume of breastmilk consumed by the infant, and the differences in the levels of hormones of insulin, neurotensin, intro-glucagon, motilin, and pancreatic polypeptide, and lower subcutaneous fat deposition are additive protective factors against developing type 2 diabetes[57].

Breastfeeding has well-known immune-modulating and protective effects against many immune and allergic disorders, especially in low-income countries[58]. Breastfeeding supports passive and active immunity in infants and young children[59]. Breastfeeding also protects against many infectious diseases in infancy and early childhood. These protective effects are dose-dependent, increasing with exclusive breastfeeding and more prolonged duration[60]. These protective and immune-enhancing effects of breastfeeding are due to its richness of many compounds that enhance both innate (such as various cellular components, lysozyme, oligosaccharides, lactoferrin, the cluster of differentiation 14, and probiotics components)[61-63] and active (such as immunoglobins A, M, and G) immunity[59]. In addition, breastmilk contains many immune-modulating ingredients, such as cytokines or nutritional components, such as LC-PUFA; vitamins A, B12, and D, and zinc[58]. Omega-3 LC-PUFA, abundant in breast milk, helps T-cell membrane stabilization, T-cell signaling, improvement, and reduction of many pro-inflammatory substances production. On the contrary, omega-6 LC-PUFAs stimulate their production[64]. Exclusive breastfeeding modulates the inflammatory status by promoting an antiinflammatory cytokine milieu and decreases gut inflammation that persists throughout infancy, adolescence, and adulthood[65-67]. The anti-inflammatory effect of breastfeeding is due to the presence of various immunoreactive and immunomodulator factors such as lactoperoxidase, lactoferrin, immunoglobins, osteopontin, superoxide dismutase, platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase, alkaline phosphatase, antioxidant compounds, bioactive factors, and many growth factors that have anti-inflammatory effects[62].

The anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects of breastmilk boost lung development and function. In addition, the breastmilk cytokines, growth factors, and maternal immunoglobins may stimulate lung growth and development, inhibit airway inflammation, and decrease the risk of developing asthma. Breastfeeding is also associated with a reduced risk of being overweight and obese and, consequently, better lung function[68-70]. Breastmilk nutrients such as B-carotene, lutein/zeaxanthin, polyphenol, and anthocyanin also affect lung efficiency[71]. Breastfeeding effects on DNA methylation provide an additional protective mechanism for the respiratory tract and improve lung development and maturation[72]. Moreover, sucking during breastfeeding stimulates the development of the diaphragm and the respiratory muscles, enhances the coordination between swallowing and respiration, and, thus, improves lung capacity[73].

The better structural and physiological neurodevelopment and cognitive and psychomotor performance associated with breastfeeding are related to many factors. Breast milk is rich in LC PUFAs, antioxidants (such as carotenoids and flavonoids), and other nutrients and bioactive factors that can induce immunomodulation and reduce oxidative stress and neuroinflammation[29,71,74]. Breast milk also contains many compounds essential for proper brain development, neurotransmitters synthesis, synaptogenesis, and intracellular communication. Breast milk is rich in LC PUFAs, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), gangliosides, sialic acid, lutein, choline, zeaxanthin, and flavonoids. These nutrients are essential in the human brain's gross and functional development[75-77]. Other social and environmental factors associated with breastfeeding, such as mother-infant bonding and educational and socioeconomic levels, may also play a role in better neurodevelopment[78].

Metabolic effects of breastfeeding

Effects on the mothers:Breastfeeding induces more favorable metabolic parameters in lactating women. It initiates a metabolic shift from pregnancy to postpartum with the alteration of resource allocation from the caloric storage stage to the milk production phase with lipid transport facilitation to the mammary gland to help in milk synthesis[79]. Stuebe[80] showed that early, high-intensity breastfeeding might help to reset the endocrine balance to shift from the insulin-resistant state in pregnancy to insulin sensitive state; thus, lactation may protect against long-term cardiometabolic health consequences. Breastfeeding induces improved glucose utilization through reduced insulin production, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and decreased B-cell proliferation[81]. Therefore, lactating women are less liable to have atherogenic blood lipids and have better glucose and lipid metabolism, lower fasting and postprandial blood glucose, low insulin levels, and more insulin sensitivity than non-lactating women, especially in the first four postpartum months[82]. In addition, lactation reduces the risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and type 2 diabetes during mid to late life[83,84]. The liver, white adipose tissues and skeletal muscles are responsible for about 50% of the mammals' metabolic rate. Breastfeeding increases hepatic mitochondrial respiration, therefore increasing the metabolic rate. In a study of rats, Hyattet al[81] showed that lactation induces PPARδ protein level changes in the liver, white adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle, which may partially clarify the observed lower blood glucose levels. A large study from Japan showed that the longer the duration of breastfeeding, the less risk for developing metabolic syndrome in women under 55 years of age[85]. The longterm protective effects of breastfeeding were also confirmed by Wiklundet al[86], who showed that breastfeeding longer than six months gives protection against obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, hypercholesteremia, and hypertension that could persist for 16 to 20 years later.

Effects on the infants:Breastfeeding has significant effects on infant metabolism through different mechanisms. Breast milk has numerous beneficial compounds that can cause epigenetic changes in genes that control metabolism or predispose to insulin resistance, diabetes, or obesity. For example, breastmilk downregulates phosphatase and tensin homolog and acetyl-CoA carboxylase beta genes, protecting against developing insulin resistance and DM[87-89]. Meanwhile, breastfeeding appears to counter the deleterious effect of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma2 Pro12Ala polymorphism on anthropometrical parameters in adolescents[90]. The liver X receptors gene expression is also modulated by breastfeeding. Activating these receptors stimulates a set of target genes needed for the de novo synthesis of triglycerides and cholesterol transport in many tissues[91]. In addition, infant serum lysophosphatidylcholine, which is positively associated with obesity risk, is affected by breast milk fatty acids composition and, interestingly, milk protein content and composition in early but not late lactation[92]. Therefore, breastfed infants are metabolically different from the infant formula regarding the lipid and energy metabolism levels (ketone bodies, carnitines, and Krebs cycle)[93]. Breastfeeding positively affects metabolic variables, anthropometric indices, and diabetesprompting genes compared to bottle feeding[87]. Breastfeeding also increases BDNF, which enhances synaptogenesis and neuronal development in infants between 4-6 mo of age[94]. This neurotrophic factor impacts numerous metabolic pathways by modifying the hypothalamus or specific neurotransmitters that facilitate food intake[95]. The effects of breastfeeding on the infant metabolism are dosedependent. Coronaet al[96] showed that the duration of breastfeeding is inversely related to the Z-score of triceps skinfold-for-age till the age of three years. On the other hand, Martinet al[97] showed that even with a long duration, exclusive breastfeeding failed to reduce insulin resistance or cardiometabolic risk parameters at 11.5 years. Therefore, the breastfeeding effect on the body's metabolism still demands additional analysis and research. We need to study why there are differences in the results of these studies and confounding factors that may impact their results.

Changes in breast milk composition with DM

Breast milk is a biologically-active, continuously dynamic fluid that significantly differs from woman to woman and from one stage to another. It is affected by various maternal factors such as term-preterm labor, maternal diet, metabolic disorders, and diseases[2,98]. DM is a chronic systemic metabolic disorder that could affect pregnant ladies with pregestational or gestational (a de novo) onset[99]. Mother with gestational DM has a 15 to 24 h delay in lactogenesis II (initiation of lactation) markers such as citrate, lactose, and total nitrogen to reach levels similar to healthy women[100]. This delay in breast milk initiation in women with gestational diabetes could be related to low levels of circulating human placental lactogen in the latter stages of pregnancy, which is positively correlated with mammary gland growth during pregnancy[101].

In addition, Arthuret al[102] and Azulay Chertoket al[103] found a significant delay in the timing of the lactose increase in the colostrum in lactating women with type 1 or gestational DM, accompanied by a reduced milk volume in the first three postpartum days, as lactose is the main osmotic ingredient in the human milk. The observed delay in citrate concentration rise in colostrum may cause a delay in the de novo medium-chain fatty acids synthesis, as citrate is essential for acetyl CoA generation from glucose[104]. Avellaret al[105] showed that women with gestational DM had higher colostrum contents of cytokines and chemokines, with increased levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-15, interferon-γ, reduced IL-1ra levels, and a decreased granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), causing altered immune composition of the colostrum. Bitmanet al[106] found that women with type 1 DM who started to pump milk at 72 h postpartum firstly gave breast milk with reduced total fat, medium-chain fatty acids, and total cholesterol but increased linoleic, oleic, and polyunsaturated long-chain fatty acid content than healthy women. These fatty acid profile changes are related to changes in specific endogenous metabolic pathways[107]. Women with type 1 DM also have impaired mammary gland lipid metabolism and high glucose and sodium contents in mature milk. However, no significant differences exist in the free amino acid profile in women with and without gestational DM[108]. The high amino acid levels in the colostrum and high levels of saturated and non-saturated fatty acid levels in mature milk in lactating women with and without gestational DM are crucial for neonatal development in the early period of life[109]. In addition, Suwaydiet al[110] showed that gestational DM has significant relationships with metabolic hormone concentrations, including ghrelin, insulin, and adiponectin. However, these relationships might be restricted to the early lactation stage.

Cardiometabolic protective effects of breastfeeding on diabetic mothers and their offspring

Breastfeeding is associated with reduced risk of type 2 DM in women with gestational DM for up to two postpartum years. In addition, breastfeeding may have long-lasting protective effects beyond two years after delivery, especially with greater lactation intensity and prolonger duration[111]. A meta-analysis by Pathiranaet al[112] showed that breastfeeding might protect against some cardiovascular risk factors, such as Type 2 DM, in mothers with a history of gestational DM. Breastfeeding for over three months is associated with the least postpartum diabetes risk in women with gestational DM[113]. Lactation enhances glucose tolerance in mothers with gestational DM, especially in the early postpartum period. Reduced estrogen levels in breastfeeding mothers might protect against impaired glucose metabolism and consequently decrease the risk of diabetes. In addition, breastfeeding decreases the risk of obesity and further reduces the risk of type 2 DM[114].

Children born to mothers with gestational DM are more prone to prediabetes, metabolic syndrome, and obesity later in life. Gestational DM is correlated with excessive fetal growth, macrosomia, and overnutrition in utero[115]. The growth pattern in children born to women with DM (including gestational DM) is slower than controls in the first two years of life, followed by rapid weight gain and consequently increased risk of being overweight, obese, and having other metabolic disorders[116]. There is a double risk of being overweight in breastfeeders from mothers with DM compared to banked breast milk feeders at the age of two years[117]. Therefore, every effort should be made to decrease these risks. However, despite the altered breast milk composition of mothers with gestational DM,e.g., reduced milk protein, there is some evidence of the beneficial effects of breastfeeding on the cardiometabolic health of their offspring. The Nurse Health study showed a significantly reduced risk of being overweight at 9-14 years in the offspring of mothers with gestational DM who breastfed for the first six months of life[118]. In addition, Onget al[119] showed that breastfeeding might give some protection against undesirable fat distribution and hypertriglyceridemia in children born to mothers with gestational DM and consequently help in reducing childhood cardiometabolic risks. In the Prima Indian study, the prevalence of DM among the offspring of mothers with gestational DM was significantly lower in those with exclusive breastfeeding than those without breastfeeding at age 10-39 years after adjustment for age, sex, and birth weight[120]. Another study assessed the effects of breastfeeding and gestational DM on Hispanic children between 8 and 13 years. They found that breastfeeding protects against developing prediabetes and metabolic syndrome in the offspring with or without gestational DM[121]. However, a meta-analysis by Pathiranaet al[112] failed to prove any protective effects of breastfeeding in IDM due to a lack of sufficient studies.

Recommendation

As breastfeeding provides adequate nutritious, easily digestible nutrients for infants, every effort should be made to encourage breastfeeding and to support the mothers to complete their mission successfully. Despite many obstacles that may enface mothers with gestational DM to start and maintain breastfeeding, every effort should be made to encourage them to breastfeed. Exclusive breastfeeding should be encouraged for 4-6 mo and complemented or supplemented for two years when possible. Information about breastfeeding, including techniques, frequency, duration, and how to overcome potential obstacles, should be available and understandable. The parents should learn and practice responsive feeding and understand the baby's cues when hungry or satisfied. The mother should also know the potential benefits of breastfeeding for her and her baby, especially when she has DM. The government should encourage and implement paid maternity leaves for at least three months to help mothers stay with their babies at home and breastfeed them. In addition, we still need to study the protective effects of breastfeeding on IDM in the short and long term. In addition, many factors are responsible for the variation of the results of the different studies, including the different methodological procedures and the differences in the target populations. Therefore, we need more extensive and multicentre studies for a longer duration and different races to ensure the beneficial roles of breastfeeding on various items of metabolic and cardiovascular health and disorders both in paediatrics and adulthood. In addition, we should request infant formula companies to do their best to mimic breast milk and reduce the gap between the advantages of breast milk and the disadvantages of infant formula. For example, these companies should revise and optimize the protein content, the amount and types of fat, and the impacts of adding probiotics, prebiotics, human milk oligosaccharides, and other well-established breast milk components.

CONCLUSION

Breastfeeding has many beneficial effects for both lactating mothers and their offspring. It protects against overweight, obesity, insulin resistance, prediabetes, DM, and metabolic syndrome in offspring regardless of gestational diabetes status. In addition, it prevents significant risk factors predisposing to cardiovascular diseases in childhood and adulthood. Therefore, every effort should be made to educate mothers about the benefits of breastfeeding for controlling DM, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension in women and their offspring.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Breast milk is the best and principal nutritional source for neonates. Breast milk is the best and principal nutritional source for neonates. Breast milk is the best and principal nutritional source for neonates.Breast milk is the best and principal nutritional source for neonates. Gestational diabetes has short and long-term effects on infants of diabetic mothers (IDM). Gestational diabetes has short and long-term effects on IDM.

Research motivation

Breast milk of mothers with diabetes has different compositions. Therefore, it is expected to have different effects than those from non-diabetic mothers.

Research objectives

We aimed to investigate the positive or negative cardiometabolic effects of breastfeeding on the health of IDM and their mothers.

Research methods

We searched different search engines and conducted a thorough literature review of the cardiometabolic effects of breastfeeding on the health of IDM and their mothers. We included 121 articles published in English between January, 2000 and December 15, 2022 in this review.

Research results

Most of the literature agreed that breast milk has many beneficial effects for both the mother and their infant in the short and long terms. Breastfeeding protects mothers with gestational diabetes against obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). There is some evidence that breastfeeding has protective effects on IDM in the short and long term. However, this evidence is not strong enough due to the presence of many confounding factors and a lack of sufficient studies.

Research conclusions

Breastfeeding has numerous favorable effects for both breastfeeding mothers and their infants,protecting the offspring against overweight, obesity, insulin resistance, prediabetes, DM, and metabolic syndrome regardless of gestational diabetes status. In addition, it prevents major risk factors that predispose to cardiovascular diseases in childhood and adulthood. Every effort should be made to teach mothers the benefits of breastfeeding in controlling DM, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension in women and their offspring.

Research perspectives

We need to study the protective effects of breastfeeding on IDM in the short and long term. We have to perform more extensive and multicentre studies for a longer duration and different races to ensure the beneficial roles of breastfeeding on various items of metabolic and cardiovascular health and disorders both in paediatrics and adulthood. We should request that those infant formula companies perform their best to mimic breast milk and reduce the gap between the advantages of breast milk and the disadvantages of infant formula.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Elbeltagi R, Al-Biltagi M, Saeed NK, and Bediwy AS collected the data, wrote and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement:The manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Bahrain

ORCID number:Reem Elbeltagi 0000-0001-9969-5970; Mohammed Al-Beltagi 0000-0002-7761-9536; Nermin Kamal Saeed 0000-0001-7875-8207; Adel Salah Bediwy 0000-0002-0281-0010.

S-Editor:Zhang H

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Chen YX

杂志排行

World Journal of Diabetes的其它文章

- Early diabetic kidney disease: Focus on the glycocalyx

- Inter-relationships between gastric emptying and glycaemia:Implications for clinical practice

- Efficacy of multigrain supplementation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A pilot study protocol for a randomized intervention trial

- Association of bone turnover biomarkers with severe intracranial and extracranial artery stenosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients

- Association between metformin and vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes

- Intermediate hyperglycemia in early pregnancy: A South Asian perspective