A Century of Chinese Animation Drawing a path with Chinese characteristics

2023-01-18ByQiuHui

By Qiu Hui

T hose most familiar with the history of Chinese animation all agree that The Monkey King: Havoc in Heaven was a milestone Chinese animation film. Produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio in 1961, the film won the Best Film Award at the 1978 London Film Festival as Chinese animation first carved out a niche in the international animation market.

This year marks the centenary of Chinese animation. Over the past 10 decades, the Chinese animation industry has forged a unique style with Chinese characteristics. In the international animation market, many Chinese animated films are making waves, including The Legend of Luo Xiaohei which was popular in Japan and Ne Zha: Birth of the Demon Child which was released in the United States.

The Wan Brothers

The four Wan brothers are considered pioneers of Chinese animation. In 1922, Wan Laiming, Wan Guchan, Wan Chaochen, and Wan Dihuan received an invitation from the Commercial Press to produce a cartoon advertisement for a Chinese typewriter. The commercial, designed in a sevensquare-meter house in Sanfengli Alley in Shanghai, became China’s first animated advertisement, filling a void in Chinese animation industry.

Four years later, the Wan brothers joined the Great Wall (Changcheng) Film Co. to produce Studio Scene. Combining live actors and cartoon images, Studio Scene was China’s first animated film.

In the 1930s, inspired by the New Film Movement, the Wan brothers began producing films with broader subjects and themes and absorbed multiple elements of traditional Chinese folk art into cartoons including shadow puppetry and trotting horse lamps.

In 1935, the Wan brothers directed and produced China’s first animated film with sound, The Camel’s Dance. In 1939, Wan Chaochen wrote and directed China’s first puppet animated movie, Going to the Frontline.

The well-received animated film Princess Iron Fan took the Wan brothers 16 months to complete by 1941. The first feature-length animated film in both China and Asia, the 80-minute movie was so popular that it was even shown in Japan and many Southeast Asian countries only 90 days after its premiere.

Chinese animated flim White Snake

The success of Princess Iron Fan made the Wan brothers realize that “genre localization is of paramount importance for the Chinese animation industry to find its unique path.”

“My brothers and I were aware that we had to avoid the influence of Walt Disney and explore our own path to find stories and subjects for animated movies,” Wan Laiming wrote in his memoir. They then included Chinese classics and folk stories into their movies and formed an animation style with Chinese characteristics.

The first “golden age” of Chinese animation movies came after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

In 1957, the Wan brothers founded the Shanghai Animation Film Studio together with many animation talents including Jin Xi, Wang Shuchen, and Te Wei, marking China’s first foray into cultivating its own animation base.

A string of excellent animated movies were produced during the “golden age” including the water-and-ink animation Baby Tadpoles Look for Their Mother, The Proud General, heavy on traditional Chinese art, and the puppet animated film The Magic Pen.

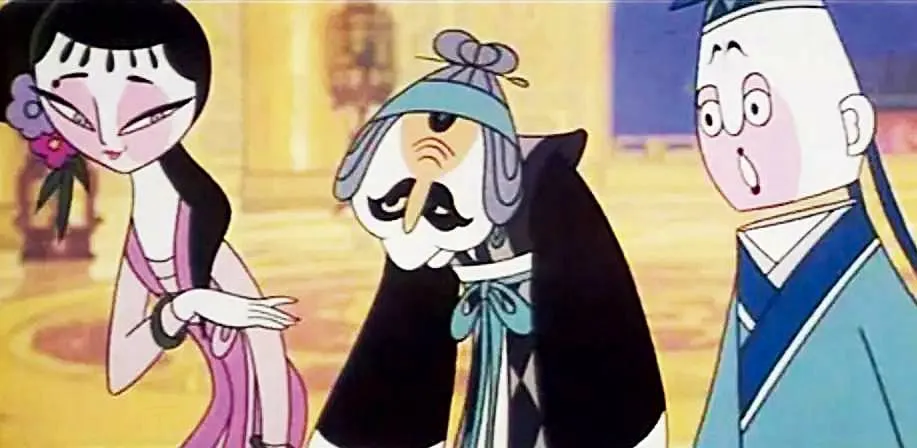

The Monkey King: Havoc in Heaven, directed by Wan Laiming and produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio from 1961 to 1964, was even more successful. It won the Best Film Award at the London Film Festival in 1978 and received wide praise from the international animation sector.

While Princess Iron Fan retained some “Disney features,” many animation experts dubbed The Monkey King: Havoc in Heaven a significant success as an entirely organic Chinese animation. To this day, it is revered in the Chinese animation industry.

The first “golden age” of Chinese animation movies came after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Localization and Internationalization

After the introduction of reform and opening up in 1978, Chinese cultural and art sectors adopted the principle of “letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend.”

China’s first color widescreen animated feature film, Nezha Conquers Dragon King, was released during this period, followed by multiple feature animated movies such as The Legend of Sealed Book and The Monkey King Conquers the Demon and series including The Story of Advanti, Adventure of the Dirty King, Inspector Black Cat, and Calabash Brothers. Many native Chinese animations remain indispensable sources of nostalgia for Chinese people.

Expert animator Yu Shui is head of the Animation Department of the School of New Media Art and Design at Beijing-based Beihang University. He called the Shanghai Animation Film Studio a “monument to the history of animation.” Yu credited it with founding the “school of Chinese animation” and spearheading singular animation styles by incorporating Chinese art elements like water-and-ink painting, Chinese paper cutting, and puppet shows.

However, traditional Chinese animation was negatively affected by foreign animation producers arriving in Chinese coastal cities. Yu recalled Shanghai Animation Film Studio experiencing a serious problem of staff outflow when many exited to do outsourced work for foreign animation companies, worsening the situation for the Chinese animation industry.

A survey by the Media Research Institute of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences showed that in 1991, 66.7 percent of animation series broadcast in Beijing were imported, with half from Disney. From 2002 to 2003, the most popular animation film and TV series among teenagers were produced by Japanese companies, followed by American animation corporations.

Both Japan and the United States have realized animation industrialization, and many Japanese and American animated films such as Transformers and Slam Dunk have been extremely popular in the Chinese market.

In contrast, the Chinese animation industry faced a bottleneck in the 1990s and early 21st Century when its targeted audience shrank from people of all ages to young children. Small kids account for the largest proportion of the audience of many representative Chinese animation films during the period such as Haier Brothers, Big-Head Son and Small-Head Father, The Lotus Lantern, Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf, and Boonie Bears.

Although The Lotus Lantern marked the Chinese animation industry entering the market economy and Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf first realized box office profits, many Chinese animation experts do not regard either as any sort of turning point for Chinese animation.

Given that foreign animated films made up the lion’s share of the market, domestic animation began “Westernizing” by imitating foreign animation, according to Yu Shui. For example, The Lotus Lantern was criticized for “Disney traces.” Yu admitted that imitation was inevitable for Chinese animation to pursue further development.

Oriental Aesthetics

In the 21st Century, many preferential policies were rolled out to boost the Chinese animation industry. The National Radio and Television Administration issued Development Plan of the Film and Animation Industry during the Tenth Five-Year Plan Period (2001-2005) in 2002 and a notice document on the development of the Chinese film and animation industry in 2004. The State Council included animation as one of the key cultural industries in the Plan on Reinvigoration of the Cultural Industry issued in 2009.

Experts believe that these preferential policies helped to avoid the “absolute Westernization” of the Chinese animation industry.

Su Da, president of Shanghai Animation Film Studio, noted in an article that Chinese animation output has been increasing since 2008, with the total length of animation produced in 2011 adding up to 261,000 minutes, leading the world.

Su noted that overemphasis on volume gave rise to a bubble in the animation industry because the quality, aesthetic level, and cultural significance did not improve.

While the reinvigoration of Chinese animation has become a common concern for both animators and fans, many experts including Yu Shui agree that 2015 was a watershed year for Chinese animation.

In 2015, The Monkey King: Hero Is Back earned a whopping 956 million yuan (US$137 million) at the box office. After only 16 days in the theaters, it overtook Kung Fu Panda 2, produced by the American animation studio DreamWorks, to become the highest-grossing movie of all time in the Chinese mainland.

Since then, a group of well-received Chinese animation films such as Big Fish and Begonia, White Snake, The Legend of Luo Xiaohei, I Am What I Am, Legend of Deification, and Green Snake werereleased in succession, boosting the confidence of Chinese animation fans. The improvement of technology and the application of traditional Chinese cultural elements empowered Oriental aesthetics to demonstrate its charm alongside the rise of the Chinese animation industry.

Inspector Black Cat

The Legend of Sealed Book

The Monkey King: Havoc in Heaven

The animated fantasy Ne Zha: Birth of the Demon Child

The first water-and-ink animation from Shanghai Animation Film Studio, Baby Tadpoles Look for Their Mother

In 2019, the animated fantasy Ne Zha: Birth of the Demon Child was a phenomenal success with over 5 billion yuan (US$715 million) at the box office, making it the second highest-grossing film ever in China.

Zhang Yiwu, professor in the Department of Chinese Language and Literature of Peking University, argued in an interview that Chinese animation is now returning to traditional Chinese narratives. He suggested that producers of Chinese animated films continue to deploy dramatic conflicts from traditional Chinese stories and fuse them with the more contemporary popular culture to tell stories from new perspectives.

Also an animation director, Yu Shui participated in the production of Folk Stories of China, an animated series from Shanghai Animation Film Studio. According to Yu, Folk Stories of China is a collection of stories rooted in traditional Chinese culture. Yu opined that Chinese animation needs to keep unique Chinese culture as the core value to distinguish itself from foreign animation and resonate with the Chinese audience.

Doing so is not easy. “It is not simply about retelling the classics and legendary stories of ancient China,” said Yu. He stressed that Chinese animation, with traditional Chinese culture at its core, must consist of values and philosophies from modern times. Only works that make Chinese culture resonate widely with contemporary audiences will achieve comprehensive recognition.

Yu Shui is confident that the reinvigorated Chinese animation industry will lead the Shanghai Animation Film Studio to a new chapter of success. Currently, Chinese animated film and TV series are growing in popularity both online and in overseas markets, with target audience and influence both expanding. The “spring of Chinese animation” is arriving.

However, Yu remains grounded and noted that China is still on the journey of developing a more diverse and mature animation industry. Some industry insiders believe that Chinese animation has not yet achieved the goal of producing “global content”.

The Chinese animation industry is now growing quickly with improved content and technologies. In the future, Chinese animation featuring Chinese culture and diverse narratives will ultimately win global recognition.

杂志排行

China Report Asean的其它文章

- Capturing ‘Ghost Gear’Discarded fishing gear continues to “fish” as the ocean’s silent killer

- Saving The Ocean From Plastic Humans are grappling with the growing plastic mess in the oceans

- NEWS in Brief

- Picturing the Times

- CHINA AND INDONESIA JOIN HANDS TO BOOST DEVELOPMENT Solidarity is key to tackling global challenges

- SOFT POWER, SOLID FOUNDATION Cultural exchanges take China-Thailand relations to new heights