Capturing ‘Ghost Gear’Discarded fishing gear continues to “fish” as the ocean’s silent killer

2023-01-18ByGuoXixian

By Guo Xixian

W hile swimming near Sea Turtle Bay in Huizhou, south China’s Guangdong Province, diving instructor Tu Nan noticed a discarded net stretched out like a wall, netting passing fish. The mesh extended so far that it took more than five minutes of swimming to find its edge. “An abandoned gill net of this size will trap many marine animals, particularly migrating fish, and subsequently prevent them from reaching their spawning ground,” Tu sighed.

Derelict fishing gear (DFG), also known as ghost gear, includes any abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear in the marine environment. Such gear randomly catches and entangles sea turtles and marine mammals, subjecting them to a slow and painful death through suffocation and starvation. Hooks and fishing lines have been found in the stomachs of dead seabirds, and coral reefs have been smothered by drifting nets.

A Pervasive Ghost

Divers from Better Blue during a 2021 ghost gear recovery operation.

With seven years of experience training divers under her belt, Tu Nan is a member of Better Blue, a non-profit organization established in 2017 by a group of diving enthusiasts with a shared goal: to clean up the sea. With more and more people joining them, Better Blue has now developed into a marine protection alliance committed to promoting participation from China’s diving community in ocean conservation and public education. “While enjoying the huge benefits delivered by the oceans, we should also take concrete action to protect the marine environment,” emphasized Tu.

“Almost every diver has encountered ghost gear underwater at some time,” she said. “They are as common as the waste you see at a crowded scenic spot.”

No one has yet been able to estimate how much DFG is currently out there. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations said in 2009 that ghost gear represented 10 percent of marine debris, equivalent to 640,000 tons per year. Science presented a more worrying picture. A 2020 article in the magazine calculated that if the 10 percent estimate was accurate, between 1.9 to 2.3 million tons of fishing gear are abandoned or lost every year considering the figure of 19 to 23 million tons of total marine litter produced in 2018.

Like ghosts, much of DFG often goes unseen, but is persistent and pervasive in the oceans. Such discarded gear traps and potentially kills marine animals and sometimes even acts as a hazard to ocean navigation, threatening the safety of mariners. According to 2018 estimates from FAO, at least 650,000 marine mammals, 700,000 seabirds, and thousands of sea turtles are caught by ghost gear each year. With respect to entanglement, DFG is considered at least three times more harmful to aquatic life than other forms of marine debris.

For animals unfortunately entangled by DFG, dying from suffocation or starvation can take months. Even after their remains begin degrading, the ghost gear continues lurking in the oceans for the next kill. “Fishing gear was originally designed to support living,” said Better Blue Co-Chief Executive Liu Xuelian. “But after being discarded, they continue to ‘fish’ and serve as a silent killer in the oceans.”

DFG is one of the main sources of plastic waste impacting the marine environment today. Cheap and durable plastic fishing gear like nylon nets and polyethylene lines have been widely used in the fishing industry. Once abandoned, they survive for hundreds of years without degradation and persistently threaten the health of marine life and the environment. After decomposing into particles smaller than gravel, microplastics are widely distributed in ocean water, coastlines, and seafloor sediments. Up to 92 percent of marine animals and their remains are found to contain microplastics. A multistakeholder alliance committed to driving solutions to the problem of lost and abandoned fishing gear worldwide, the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI) said in its 2021 annual report that between 46 and 70 percent of microplastics in the five major ocean-wide gyres resulted from DFG.

An article recently published by New Zealand scientists revealed that plastic particles have been found in Antarctic ice shelves, one of the last undisturbed places on Earth. Chemicals produced by the decomposition of plastics harm aquatic ecosystems, travel along the food chain, and eventually endanger human health. Previous studies have found traces of microplastics in human blood, lungs, and even breast milk.

Ghost gear is also responsible for the loss of 90 percent of commercially valuable fish stock. London-based non-profit organization World Animal Protection believes that about 5 to 30 percent of reduction in global fish stocks was caused by DFG. According to 2020 data from the World Wildlife Fund, crabs valued at about US$740,000 were lost to ghost fishing in one season, representing approximately 4.5 percent of the total harvest.

Retrieving Lost Gear

Two main reasons cause fishing gear to be lost or abandoned: intentional discard during illegal fishing and accidental loss due to severe weather, malfunction, or snags beneath the surface.

To address the problem, governments and international organizations have invested heavily in innovative designs and manufacturing of fishing gear as well as effective gear retrieval programs.

Eco-friendly materials such as organic fibers and biodegradable plastics have been applied in fishing net production but the output has been poorly received by fishers. “Cost-effectiveness and durability concern fishermen most, so new pricey fishing gear with a life cycle of only one or two years don’t appeal to them,” explained Liu Xuelian.

To improve government management, scientists started tracking fishing gear with physical tags, chemical markers, radio frequency identification, and satellite buoys. Traceable gear can help to identify users to push them to conduct responsible fishing operations and reduce gear loss. Gear marking can also be used by fishery regulators as a tool to identify illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activities, preventing DFG at the source. At the same time, tagging technology also helps to locate lost fishing gear and facilitates effective retrieval. FAO members approved Voluntary Guidelines on the Marking of Fishing Gear in 2018, while World Animal Protection called on countries to start tracking all fishing gear by 2025.

Members of Better Blue in Qingdao, east China’s Shandong Province.

In an exclusive recycling process in Munich, Germany, waste material from the maritime industry is used to produce trim parts for passenger vehicles. (VCG)

Determining location is a critical step in DFG recovery. Help from the fishing community has been limited because members seldom report lost fishing gear to authorities. In addition to gear marking, mechanisms to report lost or found gear quickly have also been developed for divers and tourists in addition to fishing professionals. Marine scientist Christine Ward-Paige created an app called eOceans to track ocean conditions in real time and empower the public to participate in information collection. The GGGI’s Ghost Gear Reporter app is also designed to engage a wider range of people in DFG recovery efforts.

Even when the location can be identified, retrieving the lost gear presents another challenge. “Diving naturally depends on water quality and weather conditions, and diving to collect fishing gear is quite difficult,” Tu Nan reported. Furthermore, Better Blue members often have to grapple with fishing lines and nets more than 10 meters or even dozens of meters long. The huge weight and size of some fishing gear presents a daunting challenge for divers without tools to assist with ghost gear recovery. Collecting fishing gear buried under sand is even more dangerous for divers because underwater visibility sharply drops when gear retrieval stirs up the sand. Divers receive training before each retrieval operation, but unforeseen problems happen from time to time. “Fishing nets entangle both marine life and humans, and sometimes you find yourself ensnared in a puzzle of interlocking wires,” Tu said.

Today, many non-profit organizations worldwide are working on ghost gear collection, but considering the massive volume of DFG in the oceans, such voluntary efforts represent a mere drop in the bucket. “Our influence is limited,” sighed Liu. “But we are doing everything we can to raise public awareness on the urgency and significance of marine conservation.”

Efforts to develop an alternative to manual retrieval have begun, but progress has been limited due to technical difficulties and the high cost. Solutions like sonar detection and underwater robots have been introduced, but are yet to come into widespread use.

Today, many non-profit organizations worldwide are working on ghost gear collection, but considering the massive volume of DFG in the oceans, such voluntary efforts represent a mere drop in the bucket.

Sustainable Disposal

Recycling ghost gear recovered from the oceans poses another problem. Some environmental groups and companies are leading exploration of sustainable disposal of DFG but much work remains.

According to Tu Nan, the previous practice of Better Blue was to deliver the retrieved fishing gear to a waste disposal facility for landfill or incineration. This year, they started working with a specialized company to carry out waste sorting and recycle fishing gear into plastic products. “The classification of plastics is complex, and the products made of plastics recycled from discarded fishing gear are diverse,” said Tu.

In March 2019, the Good Net project was launched as a team effort involving the International Volleyball Federation (commonly known as FIVB) and the charity organization Ghost Diving. It is aimed to remove lost fishing nets from the oceans and give them new life as volleyball nets. Transformed ghost nets have already been featured as volleyball nets in an array of FIVB events including the 2019 Beach Volleyball World Championships in Hamburg, Germany, the 2022 Beach Volleyball World Championships in Rome, Italy, and the FIVB Beach Volleyball World Tour Finals. The Chile-based company Bureo is working closely with the local fishing community to collect over 30 tons of discarded fishing nets each year and repurpose them into useful products. Luxury brand Prada’s Re-Nylon is entirely crafted from a regenerated nylon created through the recycling and purification of plastic collected from landfills and oceans.

However, recycling of discarded fishing gear remains relatively meager, and a complete industrial chain has yet to be built. Ingrid Giskes, global head of the Sea Change campaign at World Animal Protection, suggested that businesses, governments, and other stakeholders must recognize ghost gear as a major concern that demands urgent action.

In addition to technical difficulties, the poor quality of recovered fishing gear has also discouraged many companies. “The fishing nets we have collected are usually covered with moss,” Tu noted. “Considerable money and manpower are required to clean and sort recovered fishing gear to avoid secondary pollution before they are recycled.”

Compared to collecting DFG from the oceans, reusing old or worn out fishing gear collected directly from fishermen is much more cost efficient and convenient. But not many fishing professionals have shown interest in recycling their gear due to a lack of environmental consciousness and financial incentives.

“Most fishing professionals consider their gear their livelihood, and the ghost gear problem doesn’t affect them,” said Tu. She called on government policies and subsidies to educate fishermen on sustainable use and disposal of their gear and engage more firms in recycling efforts. Tu believes that every individual and organization has a role to play in the process.

Jiang Nanqing is a former officer with the United Nations Environment Programme and now secretary-general of the Committee of Green Circular and Inclusive Development under the All-China Environment Federation. At a ghost gear-themed forum in Jiaxing, east China’s Zhejiang Province, she recommended a standard system to facilitate efficient DFG recovery and higher-quality recycling.

Ingrid Giskes believes that to find effective solutions, governments and the fishing industry need to work together on ghost gear tracking, collection, and recycling and engage in joint efforts to create a safer and cleaner marine environment.

杂志排行

China Report Asean的其它文章

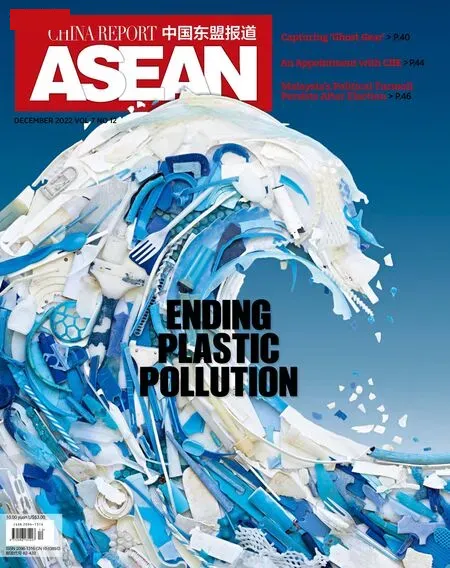

- Ending Plastic Pollution

- Embracing The ‘Asian Moment’

- CELEBRATING THE 55TH ANNIVERSARY OF ASEAN China and ASEAN pursue common development through solidarity and mutual assistance

- CHINA’S NEW ECONOMY TAKES OFF The goal is to build a modern socialist economy with Chinese characteristics

- A Century of Chinese Animation Drawing a path with Chinese characteristics

- Virtual Reality or Insanity?More brands want a piece of the metahuman marketing pixels