Observation of performance measures of STEMI in elderly after implementation of an updated protocol: results from a single center without coronary interventions

2022-12-20MiguelRodrguezRamos

Miguel Rodríguez-Ramos

General Hospital Camilo Cienfuegos, Bartolome Maso and Mirto Streets Sancti Spiritus, Cuba

As life expectancy increases, heart conditions, and especially acute coronary syndromes (ACS), are becoming a greater health issue.[1-3]Accordingly, the number of elderly patients in registries of myocardial infarction, is increasingly growing.[4,5]However, elderly patients are less likely to be treated with invasive strategy compared to younger patients, despite their intrinsic greater risk.[6,7]

Several reports have described how quality initiatives improve treatment of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Nevertheless, it is still not clear if this improvement is equal in younger as well as elderly patients.

In our region, there are few accessible reports about performance measures in elderly patients,and most of them come from centers with coronary intervention.[8-10]Even though, accessibility to this therapy is mandatory (even for this particular population), there is a shortage of data concerning quality indicators as to the attention to the elderly with conservatively treated STEMI.

In Cuba, thrombolysis with national Streptokinase (Heberkinase, CIGB, Cuba) is standard therapy in patients with STEMI who can’t beneficiate from a primary coronary intervention. Only patients from cities where this intervention is performed(La Habana, Villa Clara, and Santiago de Cuba), may receive this treatment.

Transportation of patients, between two provinces,may last more than 2 h due to the geographical characteristics of the country. In addition, most reports on this health condition focus on the description of baseline characteristics of patients, with scarce or no analysis of quality of care indicators. In the analyzed institution, an increase in secondary prevention treatment was previously reported,[11]but no measuring or comparison in the elderly patients, or between them and younger patients, has been reported yet.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the improvements in the treatment of patients with STEMI aged ≥ 75 and younger according to in-hospital performance guidelines in a center without coronary intervention, after an update of the attention protocol.

This cohort study included consecutive patients with STEMI at any stage of their in-hospital evolution admitted in the Coronary Intensive Care Unit(CICU), Department of Cardiology, Camilo Cienfuegos General Hospital, Sancti-Spiritus, Cuba between June 2014 and December 2019. The diagnostic criteria for STEMI in this study were ischemia and ST segment elevation ≥ 0.1 mV in ≥ 2 contiguous leads. The included patients were classified according to age,using as 75 years old as reference: as young (younger than 75 years old), and elderly (75 years old or older). Furthermore, two groups of elderly patients were created and a comparison was established using the date of April 2017 as reference, when the research intervention was ended. The need for informed consent and ethical approval was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

In November 2016, some updates in the attention protocols were prepared by specialists at the Cardiology Department of the aforementioned center.This is a secondary-level center lacking on-site percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which also lacks the capacity to transfer its patients to a PCI facility (in Cuba, patients have free of charge universal access to state-funded health care, with no private practices).

Concerning the study, in a first stage (March 2017),updates were focused on the primary care community doctors’ reports. Most patients from the noncapital city of the province were treated first by primary care doctors. Theorical and practical lessons were prepared in order to demonstrate the right workflow of patients with ACS, and specifically, those with STEMI. Additionally, practical information on how to administer thrombolytic medications was provided and a review of the indications of the drugs administered as part of the treatment was completed in the CICU.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC 2017)Quality of Care Working Group’s consensus on quality was selected, this time, as the framework for evaluation. This document provides a series of quality metrics distributed in eight domains: organization of network, reperfusion therapy, risk assessment, in-hospital anti-thrombotic treatment, discharge medication, patient-reported outcomes, outcomes measures, and composite quality indicators.

However, the discussion of first the domain “organization and system level structures of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) care”, goes beyond the physician’s concern, to become a policy-makers issue. Hence, it is not part of the scope of this particular manuscript.

Baseline characteristics of all patients including age, sex, and past history were collected from the hospital medical records, as well as clinical characteristics including functional state, management strategies and in-hospital outcomes. Risk factors information was obtained from older medical charts,or self-reported by patients and relatives. In-hospital death, MI and other outcomes were confirmed from review of the clinical follow-up data.

Data collected from the RESCUE study were transferred into Statistical Package for Social Sciences(SPSS, version 24, IBM, Armonk, New York), which was used for data cleaning, management, and analyses. Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage, and continuous variables as mean and interquartile range. Comparisons among different BMI groups were performed using chisquare test for categorical variables and analysis of variance test for continuous ones. AP-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Compliance was reported as a percentage of the eligible population, and for Domain 5 (secondary prevention discharge treatment) compliance with prescription of treatment was addressed only with patients who were discharged alive. The study was conducted in full conformance with principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by institutional board review.

From June 2014 to December 2019, 820 patients were admitted with STEMI at this center. Most of them were male, and white. Previous to intervention,there were 203 younger and 101 elderly; after intervention, there were 393 younger and 123 elderly. The prevalence of elderly decreased, at the first stage there were 4.4 elderly/month of study, and at the second stage, 3.0 elderly/month, a reduction of 30% (33.2%vs. 23.8%;P≤ 0.01), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of studied population.

As it should be expected, most cardiovascular risk actors were more prevalent in the elderly patients, except angina 24 hours prior index event (11.7%vs. 9.4%;P= 0.34) and diabetes mellitus (24.8%vs. 30.3%;P=0.54) which were equally prevalent in both subgroups, and tobacco consumption was the only studied risk factor which was more prevalent in youngers(62.7%vs. 41.5%;P= 0.01).

At admission there were no differences between the levels of glycaemia (7.6 (IQR: 5.5-8.6)vs. 7.4(IQR: 5.5-8.4);P= 0.5), blood pressure (127 (IQR:120-130)vs. 126 (IQR: 120-130);P= 0.52), rates of cardiogenic shock (5.9%vs. 5.8%;P= 0.63), and time from symptoms onset-first medical contact(210 (IQR: 60-240)vs. 201 (IQR: 60-240);P= 0.63).

However, more elderly patients presented with signs of heart failure than younger ones; as well as anterior myocardial infarctions; this may influence in higher mortality in elderly patients. This subgroup was quite homogeneous before and after the update of the protocol, except for, previous Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Infarction (55.4vs. 33.3,P< 0.01; and 22.7vs. 9.8,P< 0.01, respectively). In-hospital mortality rate of elderly patients was greater than younger ones, in both periods, before and after intervention.

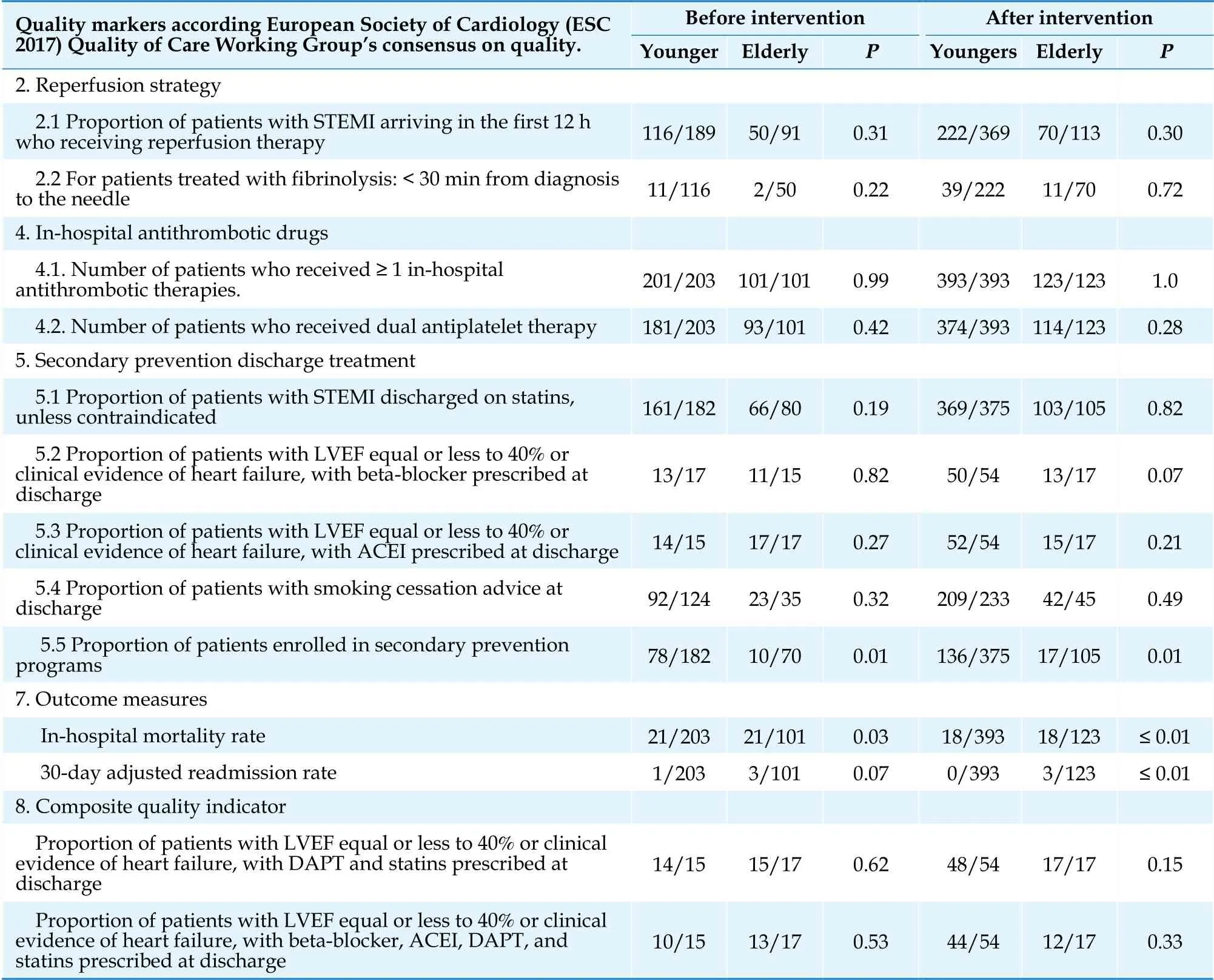

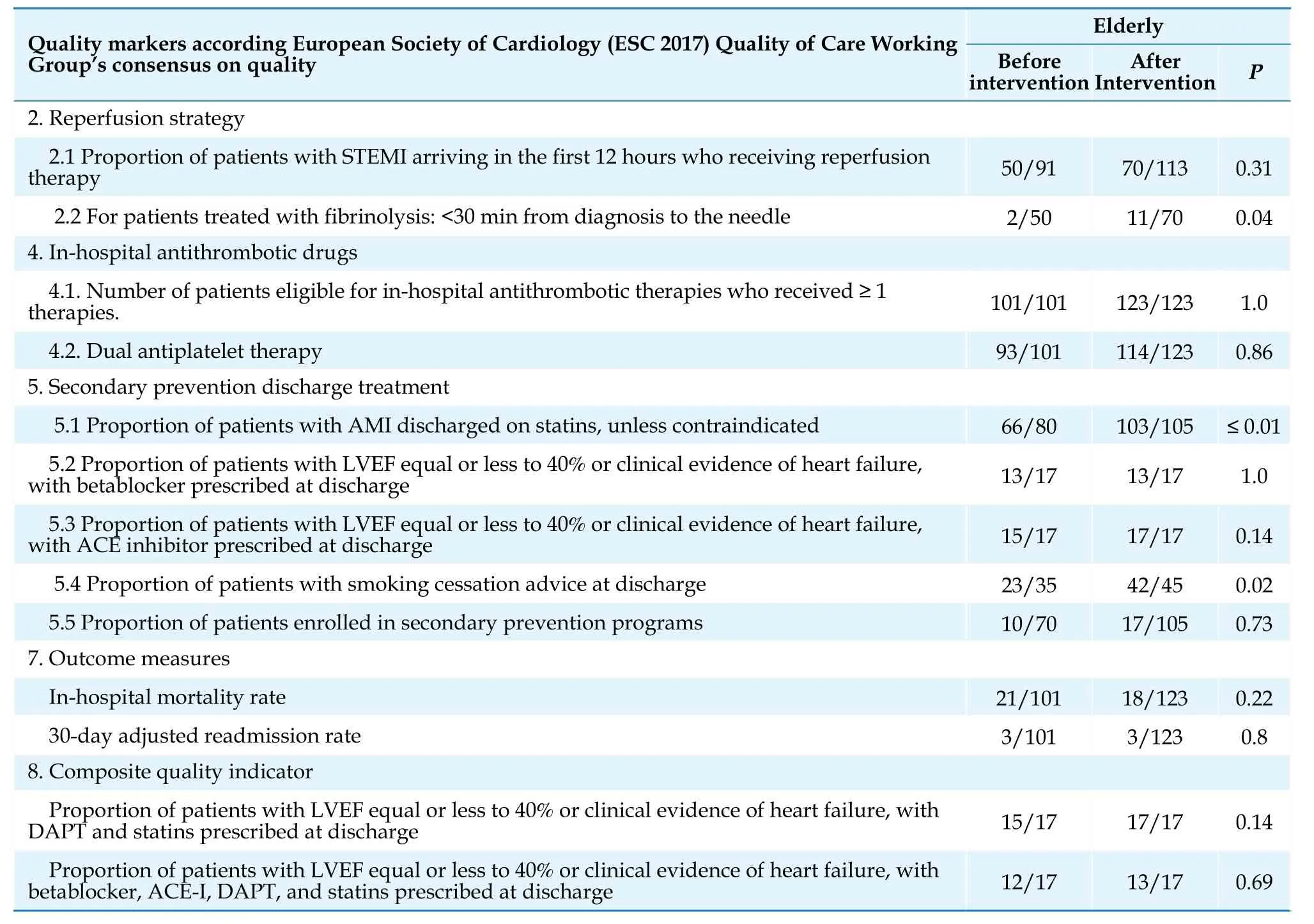

Before intervention, the proportion of elderly patients was higher than after intervention; however,the younger ones received more in-time thrombolytic treatment than the elderly. After intervention this proportion did not change. No major differences were found when analyzing other performance guidelines after or before intervention.

Concerning pharmacological treatment, this was fulfilled for more than 90% of patients. Despite age,elderly patients were treated the same as younger ones. No major differences in treatment were achieved after intervention. However, several aspects of treatment were improved, but these were not the most important aspects (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2 Performance measures of youngers and elderly according intervention group.

Table 3 Performance measures in elderly according intervention group.

The use of statins and smoking quitting advice increased their rate. Nevertheless, thrombolytic rate did not change, except the proportion of patients who received it earlier than 30 min after diagnosis. Mortality decreased significantly. Although most indicators improved, the statistical aspect was not relevant.

In-hospital risk assessment was accomplished for all patients and will not be further analyzed. Also,patient experience is not systematic collected in an official manner; however, most of them leave the institution grateful for those interventions made by the team.

In the ARIC Community Surveillance Study,[12]is stated that young patients presenting AMI are becoming increasingly common, and have high prevalence of cardiometabolic comorbidities. Diabetes was a condition with equal prevalence in both younger and elderly patients of this report and tobaccoconsumption was more prevalent in the younger ones. These observations have important health implications considering the increased disability-adjusted years of age associated with AMI at a younger age. There is a permanent need for effective preventive strategies to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease in the younger population.

While a difference in risk factor profile between youngers and elderly patients was expected,[12]the absence of it according to diabetes and heart failure was disturbing. Despite the biological age difference, younger diabetic patients may have a vascular age equal to the older population. Therefore, they may present major complications, such as myocardial infarction, in a similar proportion.[13,14]Unfortunately, no data concerning time of diagnosis until major complications were recorded.

Even though myocardial infarction in patients with heart failure is not common,[15,16]its prevalence is variable.[17,18]In our sample, despite effective thrombolytic treatment, not even patients with a previous history of AMI evolved into heart failure.

Still, these results weren’t the worst. Lower reperfusion rates were reported in several registries in our own network,[19-21]and a report states more than 95% of reperfusion in patients with thrombolytic administration between 10 and 12 h.[22]Our results may have a simple explanation. When criteria for establishing reperfusion or not were applied, our study reported the absence of reperfusion when a QS complex presented in affected derivation. This may correlate better with the clinical outcome in our sample,based on the daily practice data.

Although this has not been reported as a sign of absence of reperfusion, it is widely recognized as a pattern of established necrosis. If myocardial cells diminished by an acute necrosis, the current lesion may be diminished in amplitude, decreasing the ST segment elevation.

Concerning rendering medical treatment, once the patient arrives to a medical facility, it is administered accordingly to the guidelines.[1,2]Most drugs were given up to 90% of patients, but nitrates and beta-blockers. The former does not have a formal indication in European nor American protocols for STEMI,[1,2]although these protocols have been developed to implement coronary intervention as the choice of treatment. In settings where this technique is not routinely performed, it is still unclear whether administer nitrates and to whom.[23,24]As type 1 myocardial infarction is caused by a rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque, it might be useful to administer nitrates to patients in order to increase coronary flow.

As to beta-blockers the debate is more intense.[25-27]As an increase in early mortality has been reported,these drugs fail to achieve a level I class recommendation. However, in patients with symptoms or signs of heart failure, they are mandatory.[1,2]Besides, in elderly patients, the evolution to any way of atrioventricular blockade should be assessed.

Therefore, our effort needs to be directed to increase the number of patients with thrombolytic therapy.[28]Both strategies proved to be effective by either decreasing transfer time of the patient or system[29]or by increasing medical points to offer this treatment.[30]

Finally, several limitations need to be considered.This study was carried out in just one health center (lacking of coronary intervention, in an accessible freeof-charge health system), with retrospective analysis of a cohort of patients grouped by age, with limitations inherent to such design. Secondly, our sample may hide some relations that may appear with a larger one. Finally, follow-up data was not recorded.

To conclude, there was no difference among the studied groups according to changes in the healthcare quality indicators; however, differences were found on other non-related indicators. Several strategies should be implemented in order to increase the quality of medical attention of these patients, particularly, the rate of thrombolytic administration.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jani Y Perdomo Garces for her efforts checking grammar and spelling.

杂志排行

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Review on the management of cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly

- Migration of intra-aortic balloon pump causing obstruction of the superior mesenteric artery

- Device-based neuromodulation for cardiovascular diseases and patient’ s age

- Methodology in coronary artery bypass surgery quality assessment

- Small-molecule 7,8-dihydroxyflavone counteracts compensated and decompensated cardiac hypertrophy via AMPK activation

- Validating the accuracy of a multifunctional smartwatch sphygmomanometer to monitor blood pressure