Institutional Capacity and the Roles of Key Actors in Fire Disaster Risk Reduction: The Case of Ibadan, Nigeria

2022-12-14OlusegunJosephFalolaSamuelBabatundeAgbola

Olusegun Joseph Falola 1 · Samuel Babatunde Agbola 2

Abstract Ineffi cient and ineff ective f ire management practices are common to most urban areas of developing countries. Nigerian cities are typical examples of high vulnerability and low preparedness level for f ire disaster. This study examined the institutional framework for f ire disaster risk reduction (FDRR) and explored the roles of key actors in f ire disaster preparedness in Ibadan, a large traditional city in Nigeria. The study was anchored on the concept of urban governance. A case study research design was adopted using primary and secondary data. Primary data were obtained through f ield observation aided by a structured checklist and key informant interview. Interviews were conducted on key offi cials of the major organs for FDRR–Oyo State Fire Service (OSFS) and Oyo State Emergency Management Agency (OYSEMA). The study identif ied a disjointed and fragmented approach to f ire management. Matters relating to f ire risk reduction and disaster recovery were domiciled under the OYSEMA, while emergency response to f ire disasters was the prerogative of the OSFS. The results show that only f ive out of 11 local government areas had public f ire stations; only three f ire stations had an on-site water supply; three f ire stations lacked f iref ighting vehicles; and distribution of f ire stations and facilities was uneven. Two f ire stations responded to 80% of all f ire cases in 12 years. The study concluded that the institutional structure and resources for f ire risk reduction was more empowered to respond to f ire disaster, rather than facilitating preparedness capacity to reduce disaster risk.

Keywords Disaster preparedness · Disaster risk · Fire disaster · Fire service · Fire station

1 Introduction

The increasing f ire disaster-related loss of life, property damage, and harmful effects on the environment have attracted global attention on the need for fire disaster management based on a proactive approach that forestalls potential risks and tackles f ire hazard at the pre-stage (Dube 2015; Weekes and Bello 2019). Fire disaster management has been evolving with greater attention being drawn to preventive mechanism and preparedness measures. This is consequent on the realization that uncontrolled f ire remains a major cause of loss, injury, and destruction of lives and property (Navitas 2014; Shokouhi et al. 2019). It is thus apparent that focusing on post-f ire disaster activities, such as search and rescue and distribution of relief items to disaster-aff ected individuals alone is insuffi cient for the sustainable management of f ire and other hazards (Kasim 2014;Glago 2020).

The motivating concepts that guide f ire management throughout the world are the reduction of damage to property, protection of life, and reduction of environment degradation (Martin et al. 2007; Coppola 2015; Santín and Doerr 2016; Tymstra et al. 2020). However, the local and institutional capacity to actualize this mission is widely uneven(Agbola and Falola 2021; Bello et al. 2021). While no country, regardless of economic status and level of development,has built a capacity to be completely invulnerable to f ire disaster (Coppola 2015), cities of developing countries are particularly adjudged to have weak capacity to achieve sustainable f ire disaster management (Bello et al. 2021). Henderson ( 2004) and Hallegatte et al. ( 2020) attributed the nature of vulnerability of cities of developing countries to poor socioeconomic conditions, poor governance structure,and poor infrastructural facilities. Fire safety consideration is usually not taken seriously when planning, designing,and constructing new buildings or during repairs, renovation, modif ication, and rehabilitation of existing buildings(Woodrow 2012; Ivanov et al. 2022). The situation is worse in urban areas of developing countries where f ire disasters repeatedly take place in buildings with no evidence of incorporating lessons learned from earlier f ires (Cobin 2013).This is the commonality of f ire management in most Nigerian cities, including Ibadan.

Eff orts to manage f ire by the government through the established f ire services and the emergency management agencies have not been productive. The inherent f ire risk in Ibadan and many other cities in Nigeria is heightened by apparent prioritization of distribution of relief items that will assist aff ected individuals in recovering from the impact of f ire disaster at the expense of proactive measures involving prevention, mitigation, and preparedness. As observed by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) ( 2012), for instance, there was no budgetary allocation that was devoted to disaster risk reduction(DRR) at the state level. Virtually all of the annual allocations that were approved by the ministry of f inance were for disaster response purposes (IFRC 2012). It shows that the government is more interested in post-disaster crisis management (rescue, relief, and recovery measures) than in pre-disaster risk management (prevention, mitigation, and preparedness for prompt response).

In addition, there is no specific law geared towards addressing the underlying factors predisposing human settlements to f ire risks at all levels of government. More than a decade after it was drafted, the National Building Code(NBC) of 2006 is yet to be passed into law by the National Assembly. The existing planning laws and space standards at the federal and state levels that were supposed to curtail the spate of f ire disasters have not been properly implemented and enforced (Oyo State Government 2016; Wahab and Falola 2016; Agbola and Falola 2021).

To achieve sustainable f ire management, eff orts need to be devoted to analyzing the existing community and institutional f ire mitigation and preparedness measures in content and context. The analysis of the existing situation remains a prerequisite for adequate f ire disaster risk reduction. Consequent upon the above, this study examined the institutional apparatus and the roles of key actors in f ire disaster risk reduction in Ibadan as a prism for the situation in Nigerian cities. Key objectives pursued include:assessment of the legal and administrative structure for f ire disaster management, and evaluation of equipment and facilities available for institutional preparedness for f ire emergency.

The concept of urban governance provided the framework for this study. Governance is widely conceived to encompass national, state, and local governments and goes beyond them to include civil society and the private sector (FAO 2011; Weekes and Bello 2019). Within the f ire disaster risk context, the concept of governance expresses the aggregate willingness, capacity, and ability of diverse actors to have coordinated actions in managing risks associated with f ire hazards (CATALYST 2013). Good governance is the umbrella under which f ire disaster preparedness take place. Ensuring safety and security of urban lives and properties is a prime indictor of good urban governance(Agbola 2001 ). The impact of governance is acknowledged as critical for applying state resources to reduce disaster risks (Agbola and Alabi 2010; Bello et al. 2021). Kasim( 2014), Salami et al. ( 2017) and Hallegatte et al. ( 2020)argued that weak governance predisposed the urban settlements and city dwellers to increasing risk and vulnerability to disasters, such as f ires. This is because eff ective management of f ire disaster is dependent on appropriate policies, legislations, and strategies that are put in place to guide urban development as well as to enhance the preparedness capacity of the city (Weekes and Bello 2019).Poor or weak governance, with manifestations in the form of uncoordinated roles and responsibilities among government agencies, is a major impedance to eff ective f ire disaster risk reduction (Wahab and Falola 2016). Actionable policy and eff ective legislation are directly related to the successful preparation for urban f ire disasters (FAO 2011;FAO 2021). Good urban governance in terms of making suitable policies and laws, in conjunction with organizing public enlightenment, sensitization, and education on f ire safety, will give individuals and communities at risk a sense of belonging, and will result in effi cient preparedness measures for f ire hazard (FAO 2011; FAO 2021).

Evidence from the literature shows that previous f ire disasters in African urban areas exhibited similar commonalities of weak urban governance and associated poor emergency preparedness capacity. These include many f ire disasters in public, educational, and commercial buildings in Tanzania (Kahwa 2009), Kenya (Muchira 2012; Ogajo 2013), Uganda (Kahwa 2009; Akumu 2013), and Nigeria(Ugwuanyi et al. 2015; Popoola et al. 2016; Agbola and Falola 2021; Alabi et al. 2021). In recent studies, signif icant relationships have been established between institutional arrangements for controlling urban growth and incidents of disasters (Wahab and Falola 2016; Wahab and Falola 2018; Agbola and Falola 2021). The nature of urban growth,especially when it is not matched with infrastructure and institutional frameworks that are necessary for adequate disaster preparedness, could be a major limitation to eff ective disaster risk reduction (Agbola et al. 2012; Ojo 2013;Bello et al. 2021). Ojo ( 2013) and Bello et al. ( 2021) argued that the losses and costs incurred from disasters are best regarded as consequences of multiple institutional inadequacies (that is, environmental, economic, political, and social dimensions), which predispose cities and their inhabitants to risks. Weak or ineffi cient institutional setup manifests in forms of non-enforcement of basic f ire safety regulations(Wahab and Falola 2016); non-adherence to the building codes–a situation that hinders accessibility of f ire vehicles to reach incident sites (Kahwa 2009; Alabi et al. 2021); lack of emergency exit doors; and lack of awareness of school management and parents on matters relating to f ire safety(Kahwa 2009).

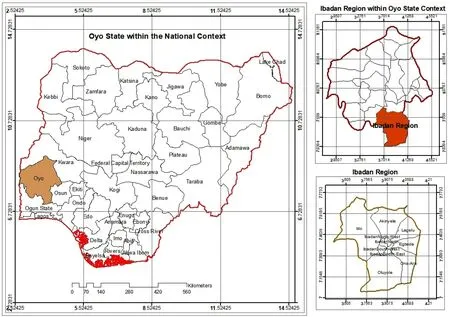

Fig. 1 Map of Ibadan within the context of Oyo State and Nigeria. Source Oyo State Government ( 2018).

According to Karen ( 2009), events such as f ire do not necessarily translate into disasters but institutional staffusually learn the advantages of emergency preparedness through diffi cult experiences. According to him, disasters can actually be managed, lessened, or totally prevented by broad, integrated disaster preparedness and mitigation measures. The foregoing attest to weak institutional capacity in most developing country cities in managing f ire disasters. This and related urban f ire management practices are assessed within the context of institutional preparedness capacity.

2 Study Area

The study was carried out in Ibadan, which is the administrative and commercial center of Oyo State, Nigeria.Ibadan is located on the Gulf of Guinea, approximately 160 km from the Atlantic coast, 142 km northeast of Lagos, and 120 km east of the Republic of Benin (Fig. 1).It comprises 11 local government areas (LGAs) out of the 33 LGAs in Oyo State. The core of the city is made up of f ive LGAs and portions of each of the remaining six LGAs within Ibadan Region. The study area covers the 11 LGAs.

The population of the city grew faster in the six outer LGAs than in the f ive core LGAs. The implication of this trend is that there is an increasing movement of population to communities in the peri-urban areas from the congested city center where land is insuffi cient for physical development (Oyo State Government 2016). Ibadan City is one of the cities having the highest population density in Nigeria with the traditional core having the highest density in the city (Oyo State Government 2018). The implication of the rapid rate of urbanization, population growth, and urban expansion for f ire disaster management is signif icant. The densely populated settlement exists within a context of improper land use planning, which has resulted in unpleasant situations and environmental challenges, such as housing shortage, poor quality housing, poor network of neighborhood access roads, slum development, and building f ire disasters (Wahab and Falola 2018; Agbola and Falola 2021). The result is a city that is more prone to building f ire disaster than ever before as documented by Agbola and Falola ( 2021).

3 Methodology

A case study design was adopted in this research. This study incorporated descriptive and normative explorations.Descriptive research was employed to understand the nature and characteristics of the research problems that needed attention. In this case, the problem was weak institutional and community capacity to manage f ire disasters in urban areas. Normative research was required to suggest how the problems should be addressed. This aspect helped in arriving at policy and practical recommendations required to improve f ire disaster management in urban environments.

The data for this study were collected from secondary and primary sources. Secondary sources included relevant record-keeping institutions, such as the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), the Oyo State Emergency Management Agency (OYSEMA), the Bureau of Physical Planning and Development Control (BPPDC) of the Oyo State Ministry of Lands, Housing and Survey (OMLS),Oyo State Fire Service (OSFS), civil society organizations(CSOs), and the Internet. Available records on major f ire disasters in Ibadan were collected from the OSFS, NEMA,and OYSEMA. Similarly, records on the level of impacts,recommended response measures, and the actual government responses were obtained from the OYSEMA. Information and documentation on f ire-related activities carried out by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the Nigerian Red Cross Society (NRCS), and faith-based organizations(FBOs) were gathered.

Primary data were obtained through f ield observations and key informant interviews. Direct observation was done to understand and get familiar with the existing situation in content and context. The direct observation was aided by a structured checklist to take inventory of available equipment in the f ire service stations. Two key informant interviews were conducted with each of the selected stakeholders in f ire management. These included offi cials of the OSFS,OYSEMA, NRCS, NSCDC, CSOs, FBOs, and landlord associations. Their roles and challenges faced in f ire disaster management were the major focus of the interview sessions. Fourteen separate interview sessions were conducted in May and June, 2020. Specif ic questions relating to their involvement in the prevention, mitigation (such as enforcement), preparedness (such as early warning systems),response/relief measures, and recovery activities were captured in the interview guide. The interview sessions involved face-to-face interaction where experts’ views on inter- and intra-agency coordination in f ire disaster management were documented. With adequate consideration of ethical issues,question schedules and voice recorders were used to record key aspects of the discussions. Consents of participants were sought and granted before interviews were conducted and before f ield observations were made.

4 Results

This section presents the results of analysis of data obtained from primary and secondary sources. The major statutory organs that are responsible for f ire disaster management were explored. The roles of key actors in f ire disaster management and their implication for f ire disaster risk reduction were reviewed.

4.1 Legal and Administrative Structure for Fire Disaster Management

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA)(Establishment Act) 1999 makes NEMA the major national specialist disaster management institution in Nigeria. The Establishment Act made the NEMA as the coordinating institution for disaster management in Nigeria. However, it is applicable only at the national level, since Nigeria operates a federal system where states are autonomous. States adopt the Establishment Act to suit their particular needs. As of 2012,22 states in Nigeria, including Oyo State, have emergency management agencies backed by law (IFRC 2012).

Fire Service, at the federal level, was established in 1901 by the British colonial government as a unit within the Lagos Police Service Department to prevent and combat f ire outbreaks in the Government Reserved Areas of Lagos Colony. It was known as the Lagos Police Fire Brigade.1http:// fedf i re. gov. ng/ about- us/

4.2 The Federal Fire Service (FFS)

In 1963, the Federal Fire Service (FFS) was established by the Fire Service Act, No. 11 of 1963 and it replaced the Lagos Police Fire Brigade. The restructured f ire service unit was placed under the Federal Ministry of Internal Aff airs and all the offi cers and staff serving in the Lagos Police Fire Brigade were also transferred to the FFS unit. At present,the FFS is a paramilitary organization under the supervision of the Minister of the Federal Ministry of Interior, with the Controller-General as its head. The FFS consists of four departments as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Federal Fire Service Organogram. Source Adapted from http:// fedf i re. gov. ng/ aboutus/.

Table 1 Public f ire service stations in Ibadan

From the review of the establishing law, the major functions of the FFS that are directly associated with managing f ire disasters in major cities are prescription and monitoring of f ire safety-related standards and encouraging the establishment of stations and f ire posts by the State Fire Services. However, these are more of passive (nonstructural) eff orts. More proactive measures are required to eff ectively manage f ire disasters.

One of the points of convergence among the technical staff of FFS that were interviewed was that the existing capacity of personnel and equipment were clearly inadequate to carry out these “ambitious” functions. One of the f ield offi cers, who had worked at FSS, Oyo State branch,for over a decade, claimed that the institutional setup and the nature of funding of FSS would have to change to achieve sustainability in f ire disaster management. Another staff of FFS, who belonged to the operations unit, argued that the resources and attention given to FSS from the central government was insuffi cient to execute the statutory functions attached to FSS.

The Oyo State Fire Service (OSFS) is the agency saddled with the responsibility of f iref ighting in Oyo State.The major institutional apparatus for f ire disaster management in Oyo State is domiciled under two government agencies–the Oyo State Emergency Management Agency(OYSEMA) and the Oyo State Fire Service (OSFS).

4.3 The Oyo State Fire Service (OSFS)

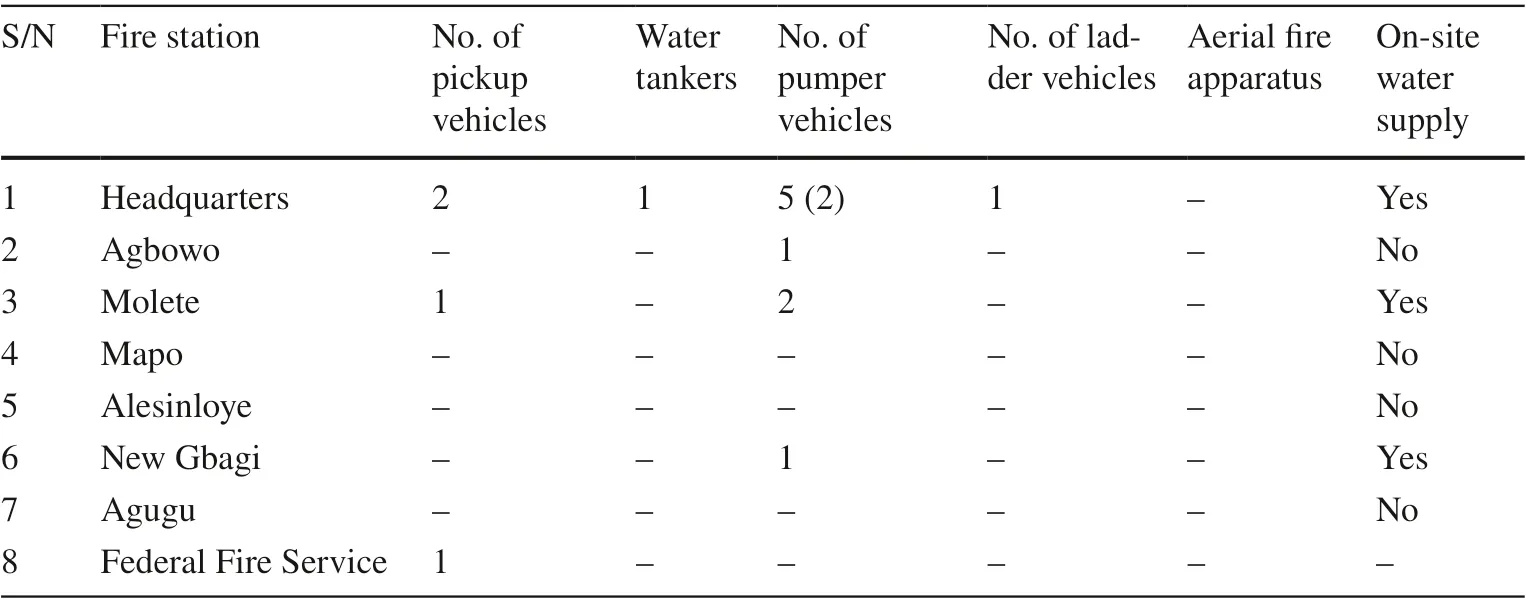

The OSFS had 15 service stations across Oyo State, of which seven were domiciled in Ibadan. Table 1 shows the details of the seven public f ire stations in Ibadan. Evidence shows that more than half (54.5%) of the LGAs in Ibadan had no government-owned f ire station (Agbola and Falola 2021).The aff ected LGAs are Ibadan Northeast, Ibadan Northwest,Akinyele, Ido, Lagelu, and Oluyole. The situation was compounded by uneven distribution of the available f ire service stations. Out of the seven f ire stations available to serve the 11 LGAs in the city, f ive f ire stations were sited at the inner LGAs. Two LGAs had two public f ire stations–Ibadan North LGA (Fire Service Headquarters and Agbowo Fire Station) and Ibadan Southeast LGA (Molete and Mapo f ires stations). One f ire station (Alesinloye) was located in Ibadan Southwest LGA. The other two f ire stations (New Gbagi andAgugu f ire stations) were meant to serve the much larger and expanding six outer LGAs. Thus, it is safe to conclude that f ire service stations were grossly inadequate in the city.

Table 2 Major equipment available in public f ire service stations in Ibadan

Three f ire stations (Mapo, Agbowo, and Agugu) could not attend to emergency f ire calls owing mainly to lack of f iref ighting vehicles. The situations at Mapo and Agugu f ire stations were worse as the stations had been dormant for over a decade. None of the two f ire stations responded to f ire emergency between 2007 and 2021.

The most equipped f ire station was the f ire service headquarters. It was the only station that had a ladder vehicle.Four f ire stations–Headquarters, Agbowo, Molete, and New Gbagi had pumpers. None of the f ire stations in the state could boast of aerial f ire apparatus. Field investigations revealed that, while there were f ire offi cers on ground,f iref ighting vehicles and on-site water supply were inadequate. As highlighted in Table 2, only three f ire stations had on-site water supply. These are Headquarters, Molete,and New Gbagi f ire stations. During an interview with one of the f ire offi cers on duty at Mapo f ire station, it was revealed that “since the f iref ighting vehicle got damaged beyond repair over a decade ago, f ire calls were always redirected to the f ire service headquarters, which was about 6 km away.”

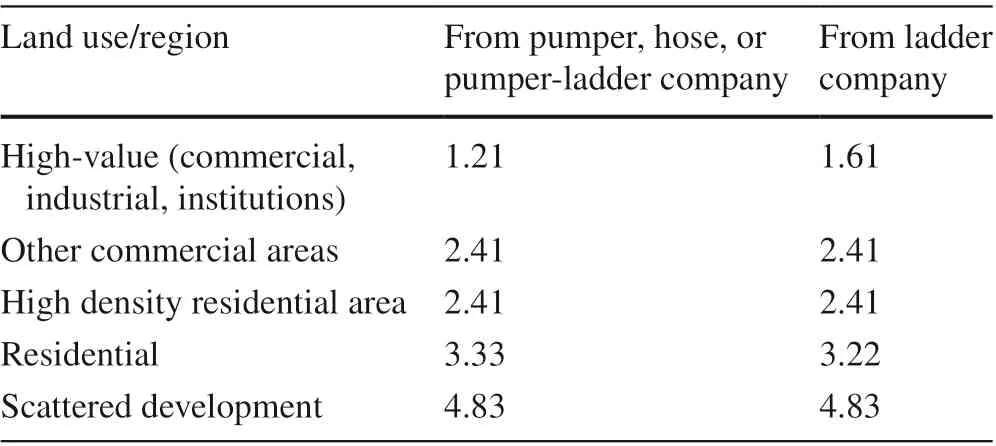

Furthermore, the available equipment in public f ire service was compared with an international standard. Best practice standards are available for estimating the adequacy of f ire stations. A typical example is the United States’ National Board of Fire Underwriters Standards (NBFU), which proposed a model for estimating the quantity of pumper, hose,and/or ladder companies needed to serve a settlement. The model is in the form of minimum standards that captures the population of the settlement, the settlement pattern, and the number and heights of buildings. Table 3 illustrates the NBFU-recommended highest travel distances in km between land use types and the nearest pumper and ladder companies.

When these standards were used to assess the situation in Ibadan, it indicated that a large majority of buildings did not meet the required standards. The result of randomlysurveyed buildings in Ibadan City showed that only 10.9%of the buildings were located within 1.5 km distance from the nearest f ire station. Those that were located within 2 km distance from the nearest f ire station accounted for 24.7%of the buildings, those located within 3 km distance were 49.2%, while those that were located within 3.5 km distance represented 56.7% of the surveyed buildings.

Figure 3 shows the f ive f ire service stations that responded to emergency f ire events between 2007 and 2018. Within this 12-year period, the f ire service headquarters responded to almost 50% (1707 f ire cases) of the total f ire events documented. Following this was Molete and Aleshinloye f ire stations, which attended to 1019 (29%) and 397 (11.3%)f ire cases, respectively. The f ire service headquarters and Molete f ire station were the only stations that were consistently active throughout the study period. Aleshinloye f ire station was inactive in 2017 and for the most part of 2018.

The lot that was meant for f iref ighting vehicles was turned into a temporary car park and warehouse for plastic retailers(see Fig. 4). Gbagi (6.6%) and Agbowo (4.5%) had relatively lower response to f ire emergencies. This is connected to the fact that Gbagi f ire station was inactive between 2007 and 2011 and Agbowo f ire station was inactive between 2015 and 2018. The main reason for the protracted period ofinactivity, according to the staff in these stations, was unavailability of f iref ighting vehicles. Other factors identif ied included unavailability of f ire extinguishers.

Table 3 Recommended travel distance (km) for pumper and ladder companies to diff erent land use types

Fig. 3 Response of Ibadan f ire stations to f ire emergency between 2007 and 2018. Source Field survey, 2019.

Fig. 4 Frontage and rear of Aleshinloye f ire station without f iref ighting vehicles and blocked with abandoned vehicles. Source Field survey,2020.

The f ire service headquarters consistently had the highest response, apart from 2007 for which the data were not available and 2010, for which Molete f ire station recorded the highest response (Fig. 3). In 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018, f ire service headquarters attended to more than half of all f ire cases, as it recorded 198 (51%), 173 (59.7%),178 (82.4%), and 161 (62.9%) f ire cases, respectively.Molete f ire station’s highest contribution to annual f ire response was recorded in 2010 with 34.9% of all f ire cases.Aleshinloye f ire station’s largest contribution (22.4%) to f ire response was also recorded in 2010. Barring year 2016, when Aleshinloye f ire station recorded the second highest, Molete f ire station was consistently the second most functional station annually.

4.4 The Oyo State Emergency Management Agency(OYSEMA)

The establishment of the OYSEMA was legally supported by the NEMA Establishment Act of 1999 and aimed at managing emergencies and disasters in the Oyo State. According to Oyo State of Nigeria ( 2009), the enabling law–Oyo State Emergency Management Agency Law, 2008–empowers the OYSEMA to carry out responsibilities of reducing disaster risks in Oyo State by formulating policy on disaster management-related activities; responding to all emergency situations; facilitating supply of resources required for search and rescue and other post-disaster crisis management activities;distributing post-disaster relief packages to disaster-aff ected individuals and groups; and advancing disaster management capacity, and organization of safety awareness and public enlightenment. Thus, the focus of the agency was meant to be generic taking into account all categories of disasters in the state. However, these functions are quite ambitious,cutting across the major phases of disaster management.Consequently, the agency has not been eff ective in all the functions. The OYSEMA singled out three key areas of function of the agency:

(1) Monitoring of the level of preparedness of organizations/agencies that may support disaster management;

(2) Facilitating public awareness and carrying out community enlightenment programs on disaster risk reduction measures; and

(3) Distribution of relief items and aid materials to disasteraff ected individuals and groups and facilitating postdisaster recovery.

The f irst two functions are proactive (pre-disaster) measures while the third function involved post-disaster (crisis)response. Based on the f ield study, the OYSEMA was more active in the post-disaster response activities. Evidence from the f ield survey and the review of major activities of the agency showed that the core areas of involvement of the agency in f ire management were: coordination and facilitation of supply of resources required for search and rescue and other post-disaster crisis management activities within the state; collation of data from the OSFS on f ire disaster and vulnerable communities in order to facilitate disaster risk management; and distribution of relief items and aid materials to disaster-aff ected individuals and groups and facilitation of post-disaster recovery.

On facilitating the provision of resources for search and rescue activities, for instance, the OYSEMA assisted in clearing burnt debris at the Molete f ire disaster that occurred on 14 October 2014. It was documented that the debris evacuated included 10 cars, two buses, one tricycle, 10 motorcycles, and one tanker truck (trailer).

Concerning collation of fire disaster data, the field study showed that the OYSEMA regularly requests formal f ire records from the OSFS. However, the f ire record that the agency had was a summary of the monthly f ire cases,which was not detailed enough for adequate analysis. There was no structure in the OYSEMA for documenting all f ire disasters that occur in the state. There were only records of f ire disasters that were assessed for possible government aid measures.

On the distribution of relief materials to f ire-aff ected persons, the agency worked on an observation-assessmentrecommendation basis. The f irst step is to observe the postdisaster situation to conf irm (with pictorial evidence) that the incident did occur and to validate the claims of the aff ected persons. In most cases, the f ire-aff ected persons,groups, or organization would write to the state government to request assistance. This often attracted some form of lobbying and politicking to facilitate such requests. The request would then be forwarded to the OYSEMA for appropriate actions. Following a request, the agency would carry out a detailed assessment of the f ire disaster, in terms of the nature, causes, and location of the disaster, and estimated losses and name(s) and address(es) of the aff ected persons.This would be done by setting up a team of assessors to conduct on-the-spot assessments at the scene of the f ire disaster and write a report. The report would be analyzed to ascertain if the level of damage exceeded the coping capacity of the aff ected persons and if there would be need for the government’s intervention to facilitate recovery. Having evaluated the f ire disaster, the agency would make a decision in the form of recommendations to the state government on the need to assist the aff ected persons in recovering from the impacts. The detail of the proposed intervention would be attached to the report that would be forwarded to the state Governor. The agency would then wait for further directives from the Governor to take further actions.

The relief packages distributed by the government through the OYSEMA included household goods (cooking pot, cooking kettle, cooking stove, mosquito net, blankets,bucket, detergents, soaps, clothes, towels, bed sheets, mattresses, mats, pillows, and food plates); food items (beverages, noodles, drinking water, rice, beans, maize, and cooking oil); and building materials (roof ing sheets, cement,planks, and nails). Premised on its budgetary provision, the bulk of the expenditure of the agency was usually on this aspect. In its annual statistical analysis of distribution of the relief materials published in 2015, it was disclosed that“As a way of mitigating the eff ect of disaster on victims,the agency in collaboration with NEMA distributed relief materials worth billions of Naira in the Year 2014 across the length and breadth of Oyo State”.2https:// oyost ate. gov. ng/ oyo- state- emerg ency- manag ement- agencyIn the 2016 version of the report, it was documented that the agency in 2015 “distributed relief materials worth millions of Naira to the victims of f ire disaster at Gaa Garuba in Iwere-Ile Local Government Area.”3https:// oyost ate. gov. ng/ oyo- state- emerg ency- manag ement- agencyIn September 2016, almost a year after the December 2015 f ire disaster that occurred at Iso-Pako market in Sango, the OYSEMA revealed that “relief materials worth several millions of Naira were distributed to victims of [the]f ire disaster [...] to cushion the eff ect of damages done to the victims.” However, formal lists of expenditure on relief materials were not made available for further analysis.

The OYSEMA revealed that prior to the 26 August 2011 f lood disaster that aff ected all 11 LGAs in Ibadan, the agency employed traditional disaster management strategies that emphasized relief measures, which became ineff ective and largely reactive as opposed to being proactive in reducing risk. More eff ort and resources were channelled to postf ire disaster management while little eff ort was focused on f ire disaster risk reduction. In one of the few pre-disaster measures carried out in 2012, the OYSEMA organized f ire drills at selected public agencies to create awareness of f ire disaster risk reduction in workplaces and carried out community awareness and enlightenment activities by distributing handbills, f liers, pamphlets, and posters. However, these are mostly conducted in communities where f ire disasters recently occurred, at the point of assessment of post-f ire damage and or during distribution of relief package. In addition,most of these measures focused on f loods, rain storms, civil strife, and road crashes. Another proactive measure undertaken was collaboration with a radio station (Impact Business Radio) in disseminating information on disaster risk reduction and communicating early warning to the public.

4.5 The Emergence of Private Fire Service Providers

Field investigations and observations revealed that government-owned f iref ighting services in the study area were often done on a spontaneous and ad hoc basis. This was mainly due to the lack of adequately equipped f ire stations and personnel to carry out proper routine and methodological preparations and guidelines for f iref ighting. Although the Oyo State government sponsored television and radio campaigns, warning on the risks and danger of f ire during the dry season, long-term prevention and mitigation of urban f ire seemed to be absent.

Owing to this inadequacy, attempts at managing f ires were made by some public and private institutions and organizations. Specif ically, the Ibadan Depot of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) in Ido LGA; the University of Ibadan and the Polytechnic, Ibadan in Ibadan North LGA;the Central Bank of Nigeria, Oyo State branch; Cocoa and Heritage Malls in Ibadan Northwest; and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) in Akinyele LGA all have dedicated sections equipped for f iref ighting.

The results of separate interviews conducted in all these private organizations pointed to the failure of the government f ire service (OSFS and FSS) to provide prompt and required service during f ire emergencies. Previous f ire disasters that damaged buildings and properties compelled the organizations to set up well equipped modern firef ighting sections within the premises of the organizations.For instance, the procurement of f ire trucks at the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Ibadan branch, located at Dugbe in Ibadan Northwest LGA, was a response to the February 2006 f ire disaster that destroyed the 7th f loor of the building that contained the conference, development, and f inance departments. It was reported that the f ire had raged for over three hours before OYSF could quench the f ire.

Similarly, the Cocoa and Heritage Malls realized the urgency of a private f ire service after one of the outlets that was occupied by a cinema was destroyed by a f ire disaster in January 2015. The mall’s management employed the services of a private f ire service to prevent recurrence. Similarly, recurrent f ire disasters in student halls of residence,staff quarters, faculty, departmental, and administrative buildings at the University of Ibadan in Ibadan North LGA informed the construction and equipping of a modern f ire service section.

5 Discussion

In practice, the management of f ire disasters by government institutions is mainly reactive. Diff erent public agencies were responsible for diff erent aspects of disaster management. Our results suggest weak institutional preparedness capacity, resources, and equipment to eff ectively manage f ire disasters in buildings.

From the review of the administrative structure of FFS, it is apparent that the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, which is the administrative and political headquarters of Nigeria,was the best equipped city in terms of f ire service personnel and equipment. The fact that the FFS did not have its offi ces and stations in all the states of the federation is also a testament to this. The gross inadequacy of personnel and equipment agrees with Agbili’s ( 2013) f indings that among paramilitary forces and agencies in Nigeria, the federal f ire service was the least equipped in terms of infrastructure and staff . Agreeing with Egunjobi and Falola ( 2017), many state governments, mindful of the low coverage of the FFS and their social and constitutional responsibilities to protect lives and property, established state-owned f ire services.

The OSFS had the mandate to ensure eff ective f ire mitigation, preparedness, and response in Ibadan City. However,the available equipment and personnel pointed to weak preparedness capacity to tackle emergency fire events.The agency was not furnished with adequate institutional apparatus to prepare for f ire disasters. Fire stations were inadequate and the available ones were clustered in space.Fire service stations, f iref ighting vehicles, and water supply were grossly inadequate as only f ive out of the 11 LGAs in Ibadan had a public f ire service station. Available f ire stations fell short of international standards. This shortage was compounded with uneven distribution of f ire stations across LGAs and lack of adequate f iref ighting equipment. The fact that f ire stations were not evenly distributed implies that the level of preparedness varied across the city. Similarly, the available f ire stations had diff erent preparedness capacities based on diff erences in facilities, equipment, and personnel,as also revealed by Jonsson et al. ( 2017). The gross inadequacy of f ire stations and f iref ighting equipment, as identif ied in this study, is a root cause that subjects Ibadan to high vulnerability to f ire disaster. The high level of inadequacy of f iref ighting equipment has implications for institutional preparedness for a f ire emergency. This, according to Agbola and Falola ( 2021), makes it diffi cult to ensure that vulnerable people gain prompt response to a f ire emergency. Fire stations were not just inadequate; even the available ones were not adequately equipped. This f inding supports the assertion of Agbola and Falola ( 2021) that no f iref ighting vehicle has been procured in the city in 15 years.

Our results suggest that the OYSEMA’s basic role in f ire management was more of a channel where the state government provides aid measures and distributes relief items to individuals or groups aff ected by f ire disasters. The best proactive measures that the agency undertook included awareness campaigns, community sensitization, and education on f ire safety precautions and risk reduction, which were mostly done through media jingles on radio and television stations. In corroborating this f inding, a civil servant retiree who had lived in Ibadan for over three decades revealed during an interview that the ruling parties often preferred to support individuals or groups that are directly aff ected by f ire disasters by providing them with building materials (like roof ing sheets and bags of cement), household goods (like mattresses and bed sheets), and money. This, according to him, was “to score political points” and win the hearts of the electorate.

There was no integrated institutional coordination for f ire management between the three statutory bodies saddled with the responsibilities to manage f ire emergencies. This poses a great burden on preparedness capacity. The bulk of state resources was channelled towards post-disaster relief and aid distribution to disaster-aff ected persons through the OYSEMA while the pre-disaster mitigation and preparedness phases (mainly executed by OSFS) were poorly funded.The lack of synergy among emergency agencies was consistent with previous studies, such as Jonsson et al. ( 2017),which identif ied increased f ire risks as a result of inadequate cooperation between relevant urban departments. The result was also in line with Wahab and Falola’s ( 2016) f indings that attributed urban encroachment on high disaster risk areas to lack of coordination among stakeholders in disaster management.

During the post-f ire disaster reconstruction phase, little emphasis is placed on structural mitigating measures,such as provision of f ire hydrants, f iref ighting equipment,sprinklers, and f ire alarms in buildings. The relationship between increased f ire disaster risks and failure to prioritize preparedness measures, like lack of f inancial commitment to setup f ire stations and to purchase f iref ighting vehicles,was established in previous studies, such as Jonsson et al.( 2017) and Shokouhi et al. ( 2019). Consequent upon institutional preparedness inadequacy, attempts at managing f ires were made by some public and private institutions and organizations to set up well-equipped modern f iref ighting sections within the premises of the organizations. These organizations pointed to the failure of the OSFS and FSS in providing required service promptly during previous f ire emergencies.

6 Recommendations

There was a consensus among stakeholders in fire management that, instead of putting so much resources on relief distribution, the government should focus more on sustainable approaches to fire disaster management,such as fire risk awareness, training on fire risk reduction, enforcement of fire safety regulations, equipping and expanding the state fire service, and distribution of fire safety materials.

This study revealed that the major contributions of the NEMA and OYSEMA to f ire disaster management were reactive, mostly in the forms of search and rescue activities and distribution of relief materials. There is a need to shift focus from this post-disaster response to more proactive measures of disaster prevention and mitigation. This can be done by investing more in the distribution and installation of f ire prevention/suppression items to building occupants and communities. This should be complemented with training on how to use the f ire safety items. Fire hydrants should be made available to all major markets and vulnerable communities in the city. This will complement the activities of the f ire service during emergencies. When f ire safety items,such as extinguishers, f ire blankets, f ire alarms, and sand buckets are distributed or made available at subsidized prices to individuals, groups, and communities, the need to distribute relief items to f ire-aff ected individuals and groups will reduce. This is because f ire safety consciousness would increase, f ire disasters would occur less frequently, damages caused by f ire would be reduced, and f ire services would be more eff ective.

The success of these recommendations will require drastic policy change that hinges on political will. The readiness to make and institutionalize sustainable f ire management policies rests on the city managers who are predominantly politicians. However, this can be championed by stakeholders in f ire management, which include professionals such as city planners, builders, engineers, and architects; professional organizations and groups in the built environment sector such as the Nigerian Institute of Town Planners (NITP);government and multinational organizations; NGOs such as the NRCS; and community-based organizations (CBOs)such as landlord or tenant associations and market associations. While professionals who practice in public agencies cannot speak or act against the government, they can work through professional bodies, the CBOs, and NGOs to eff ect changes that will favor sustainable urban settlement. These are interest groups that can advocate and lobby for policy change on sustainable f ire management practices in the city.

7 Conclusion: Policy Implications of the Existing Institutional Structure for Fire Disaster Management

This study highlights the legal and administrative structure for f ire disaster management, with emphasis on equipment and facilities available for institutional preparedness for f ire emergency in a typical Nigerian city, Ibadan. The management of f ire disaster was disjointed as post-disaster response and recovery activities were prioritized at the expense of pre-disaster mitigation, prevention, and preparedness measures. This study revealed that the state emergency management agency was more empowered to respond to f ire disasters, rather than reducing vulnerabilities to f ire disasters through effi cient preparedness measures. In other words,more resources were devoted to crisis management (such as search and rescue and aid measures) rather than risk reduction (mitigation and preparedness).

The government channelled more eff ort and resources to post-f ire disaster management while little eff orts were focused on f ire risk reduction. There was a lack of state investment in long-term vulnerability reduction through structural measures (such as provision of community water supply and hydrants and establishment of more f ire stations)and nonstructural measures (such as enforcement of f ire safety regulations and creation of public awareness on f ire safety). As evident in this study, there was a disjointed and disintegrated approach to f ire management. Matters relating to f ire risk reduction were domiciled under the OYSEMA,while emergency response to f ire disasters was the prerogative of the OSFS. Consequently, management practices in anticipation of f ires were weak on the parts of the government, communities, and individuals; and adequate actions were not taken to improve the capacity of communities and institutions to prepare for emergency events. These inadequacies are subject to weak urban governance.

Open AccessThis article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http:// creat iveco mmons. org/ licen ses/ by/4. 0/.

杂志排行

International Journal of Disaster Risk Science的其它文章

- Sendai Framework’s Global Targets A and B: Opinions from the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction’s Ignite Stage 2019

- Perceptions About Climate Change in the Brazilian Civil Defense Sector

- Is Being Funny a Useful Policy? How Local Governments’Humorous Crisis Response Strategies and Crisis Responsibilities Inf luence Trust, Emotions, and Behavioral Intentions

- The Eff ect of Natural Hazard Damage on Manufacturing Value Added and the Impact of Spatiotemporal Data Variations on the Results

- Understanding Farmers’ Preferences Towards Insurance Schemes that Promote Biosecurity Best Management Practices

- Disaster Impacts Surveillance from Social Media with Topic Modeling and Feature Extraction: Case of Hurricane Harvey