Endoscopic mucosal resection-precutting vs conventional endoscopic mucosal resection for sessile colorectal polyps sized 10-20 mm

2022-12-09XueQunZhangJianZhongSangLeiXuXinLiMaoBoLiWanLinZhuXiaoYunYangChaoHuiYu

Xue-Qun Zhang, Jian-Zhong Sang, Lei Xu, Xin-Li Mao, Bo Li, Wan-Lin Zhu, Xiao-Yun Yang, Chao-Hui Yu

Abstract

Key Words: Colorectal polyps; Medium size; Polypectomy; Endoscopic mucosal resection with circumferential precutting; Conventional endoscopic mucosal resection

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in men and second most common cancer in women[1]. In China, the incidence and mortality rates of CRC showed an increasing trend in 2000-2011;approximately 376.3 thousand new CRC cases and 191.0 thousand CRC deaths occurred in 2015[2],posing a severe threat to people’s health. Endoscopic resection of colorectal polyps has proven effective in reducing CRC incidence and mortality[2,3]. Currently, all polyps must be resected except for diminutive (≤ 5 mm) rectal and rectosigmoid polyps as they are predicted with high confidence to be hyperplastic[4].

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is a well-established method for removing sessile colorectal polyps. However, as the polyp size increases, the piecemeal resection rate increases[5,6], which is a wellknown risk factor for local recurrence after EMR[7-9]. Although endoscopic submucosal dissection(ESD) has been increasingly used to overcome the disadvantage of EMR, the technically challenging,time-consuming practice and longer hospital stay required limit its wider use[10]. Recently, EMR with circumferential precutting (EMR-P), an alternative to conventional EMR (CEMR), has emerged as an effective method[11,12]. However, most comparative studies were retrospective, with a small sample size, involving large (≥ 20 mm) or difficult lesions (whereen blocresection could not be achieved by CEMR), and the quality of evidence was relatively poor.

To date, no high-quality evidence or specific recommendation is available in recent guidelines for the optimal resection of 10-20 mm sessile lesions. Therefore, a prospective comparative randomized study was conducted to compare the efficacy of EMR-P with that of CEMR in medium-sized (10-20 mm)colorectal polyps.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial involved seven Chinese institutions: the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University (Institution A); Renmin Hospital of Yuyao City, Zhejiang (Institution B); Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital, Zhejiang (Institution C); Taizhou Hospital, Zhejiang (Institution D); the Central Hospital of Lishui City, Zhejiang (Institution E); Ningbo Medical Center, Lihuili Hospital, Zhejiang (Institution F); and Ningbo First Hospital, Zhejiang(Institution G). The trial complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine,Zhejiang University (No. 20191477); Ningbo First Hospital, Zhejiang (No. 2020-R013) and other participating institutions. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04191473).

Patients

Patients aged ≥ 18 years undergoing endoscopic resection for colorectal mucosal lesions (adenoma,intramucosal adenocarcinoma, or sessile serrated adenoma/polyps) 10-20 mm in size were included.Endoscopic diagnosis of mucosal lesions was based on macroscopic appearance[13], narrow-band imaging (NBI) findings, or classification of pit patterns on magnifying chromoendoscopy (MCE).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Pedunculated lesions; (2) residual lesions after endoscopic resection; (3) lesions with submucosal infiltration judged by advanced endoscopic imaging; (4) lesions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease; (5) familial polyposis; (6) electrolyte abnormality; (7)coagulation disorders; (8) severe organ failure; and (9) patients who were pregnant or nursing and who were taking NSAID drugs or anticoagulant medications. All the patients were informed of the research aims and endoscopy procedures and provided written informed consent for research participation.

Procedures

Colonoscopy was performed after bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol solution, magnesium sulfate, or sodium phosphate subject to the common practice of each center (the detailed information of used materials in each institution was listed in Supplementary Table 1). In both polypectomy procedures, a high-definition lower gastrointestinal endoscope was used (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo,Japan). In both groups, whether a cap was used or the bowel lumen was filled with air or carbon dioxide was left to the preference of the endoscopist. When the colonoscope reached the lesion location,NBI or MCE was used to identify the presence of submucosal invasion. If necessary, endoscopic ultrasound examinations were performed. When the lesion was confirmed to be noninvasive, EMR-P or CEMR was subsequently performed.

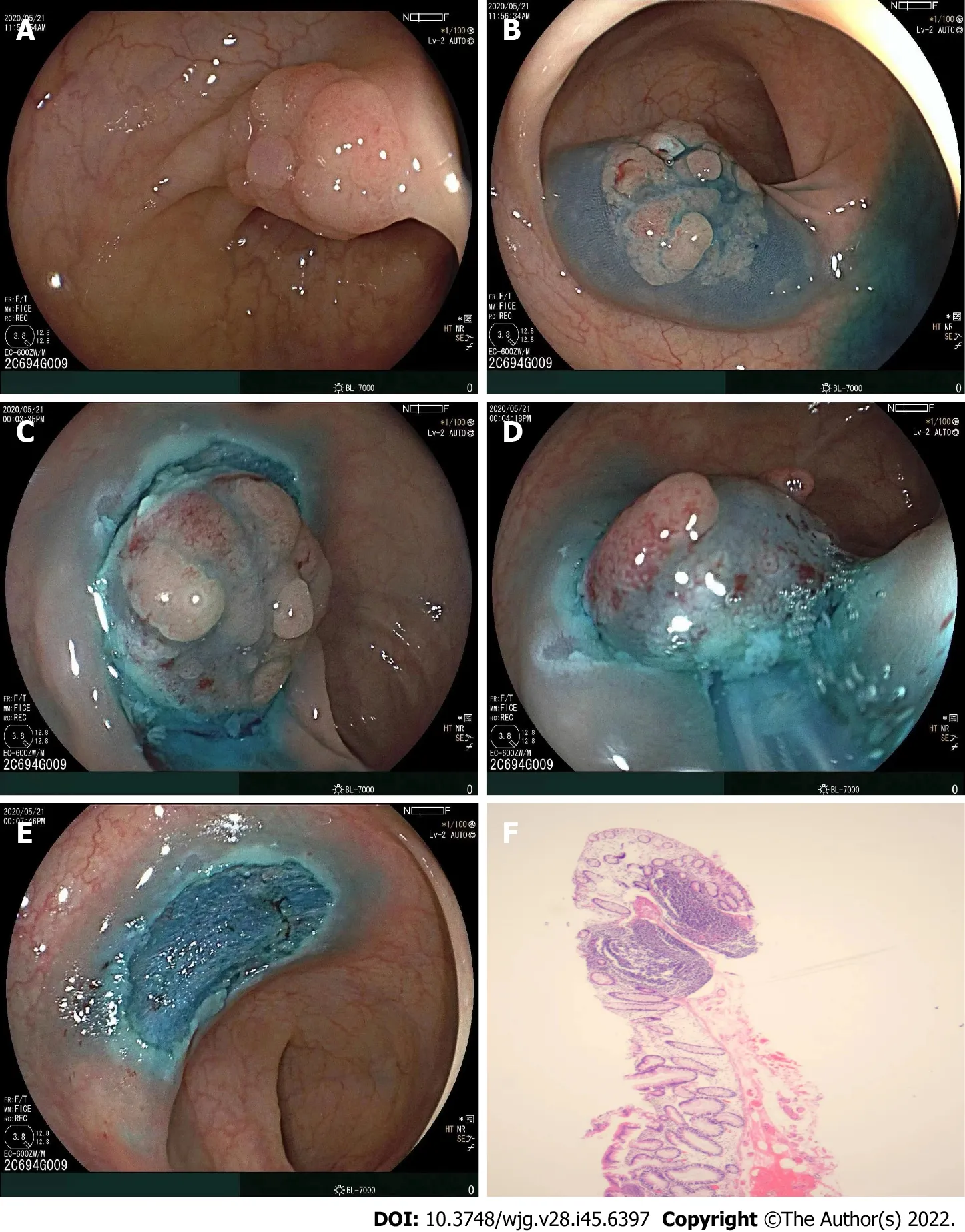

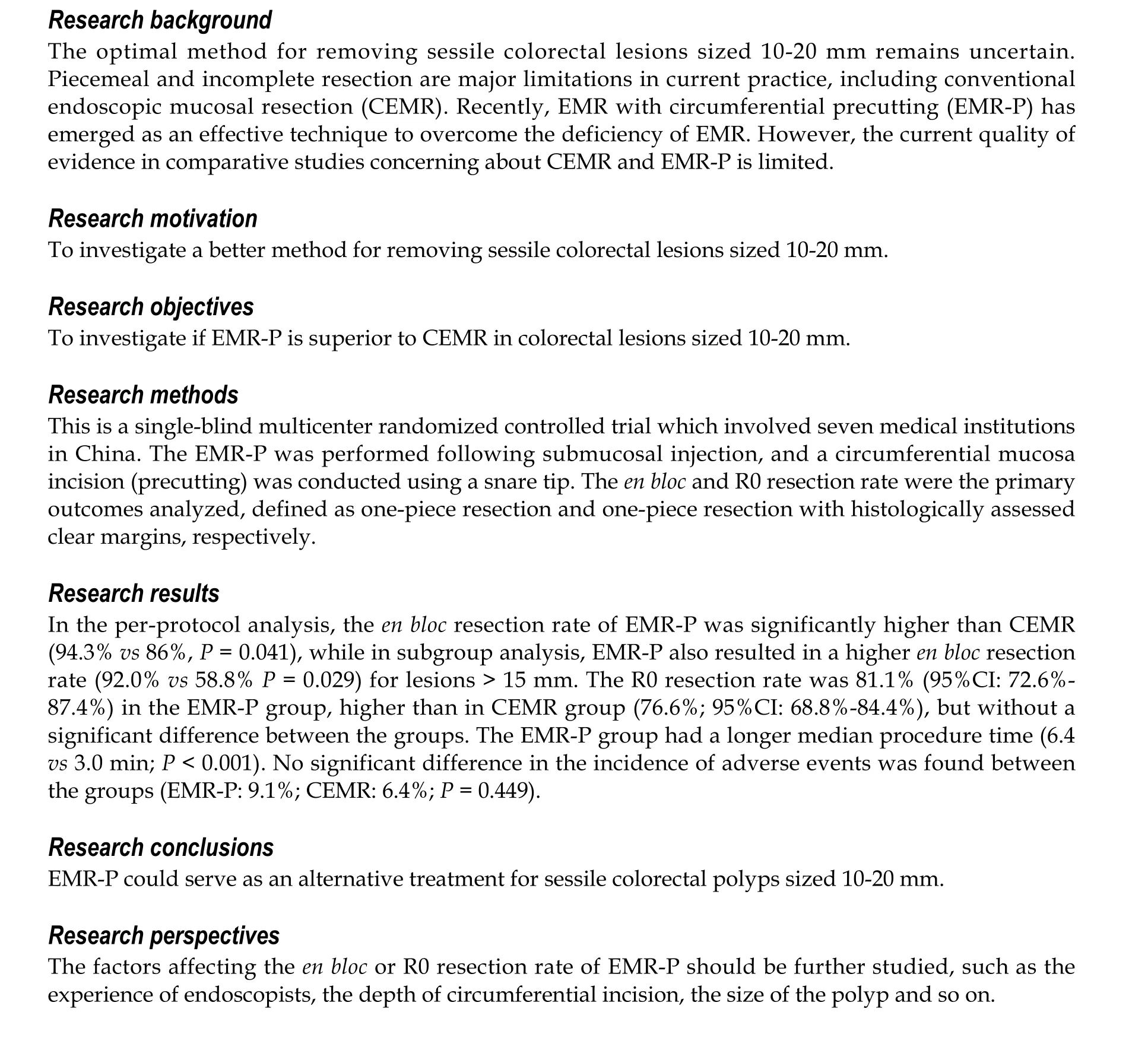

The EMR-P procedure included the following steps: (1) Submucosal solution injection; (2) a fully circumferential mucosa incision (precutting) using a snare tip to separate the lesion from the surrounding non-neoplastic mucosa (the polypectomy snares were chosen at the discretion of each institution); and (3) snaring the circumferential lesion and removing the tumor in the same manner as for CEMR. Following resection of the lesion, hemostatic forceps (with or without argon plasma coagulation) were used to prevent postoperative bleeding (Figure 1).

The Paris classification was used to classify the morphology of polyps with superficial appearance(category 0): Polypoid type [lesions 2.5 mm above the mucosal layer: Pedunculated (0-Ip), sessile (0-Is),or mixed (0-Isp)], nonpolypoid [lesions less than 2.5 mm (0-IIa), flat (0-IIb), or slightly depressed (0-IIc)],and mixed types[14].

Regarding patients with multiple lesions, only the lesion closest to the anus and sized 10-20 mm was registered to remove the subjective bias of researchers. All operations were performed by certain endoscopists in each center. Experienced endoscopists were defined as those who had performed > 1000 colonoscopies, > 300 EMRs, and > 10 ESDs. Compared with the size of open (approximately 7 mm) or closed (approximately 2 mm) biopsy forceps according to its endoscopic appearance, the size of the lesion was initially estimated and then was confirmed by comparison with an opened snare (20-30 mm)during treatment.

Randomization and concealment

Figure 1 Following resection of the lesion. A: A sessile lesion (15 mm × 13 mm) located in the sigmoid colon; B: Submucosal injection of glycerol fructose was applied; C: A circumferential incision was made using a snare tip; D: The snare could grasp the submucosal tissues below the mucosal lesions; E: En bloc resection was achieved with no complications; F: Histological diagnosis was tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia (20×).

The SPSS™ Statistics (version 21; Chicago, IL, United States) software was used to generate random numbers, and simple randomization was adopted to determine whether the EMR-P or CEMR grouping depended on a 1:1 ratio. The operation method corresponding to the random numbers was sent to each center within a closed envelope by the research coordinator. A randomized competitive enrollment mode was applied at each center until the envelopes were allocated completely. Every enrolled patient received an envelope, but the grouping information was blinded for them during the endoscopic procedures. Only immediately before starting the colonoscopy was the operator informed of the treatment allocated by a research assistant.

Outcome variables

The primary study outcomes were a comparison of the R0 anden blocresection rates between the groups. The secondary outcomes included procedure time and adverse events (intraprocedural bleeding, postoperative bleeding, or perforation).En blocresection was defined as one-piece resection,and R0 resection was defined as one-piece resection with histologically clear margins of lesions. Non-R0 resection included a positive resection margin (R1) or an unclear resection margin (RX). The procedure time of both polypectomy techniques was measured from the start of submucosal injection to complete removal of the polyp. Intraprocedural bleeding was defined as bleeding occurring during the procedure that persisted for more than 60 s and required any form of endoscopic hemostasis (e.g., endoscopic coagulation or mechanical therapy, with and without adrenaline injection)[4]. Postoperative bleeding was defined as, within 14 d after EMR-P or CEMR, hematochezia, with a > 2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin or requiring endoscopic hemostasis. All the patients were followed up within two weeks after the operation to assess the presence of any adverse events.

Sample size

It was hypothesized that EMR-P would be superior to CEMR for endoscopic R0 resection of colorectal polyps sized 10-20 mm. As previous studies reported that the CEMR R0 resection rate for colorectal polyps 10-20 mm in size was 40%-60%[15], it was preliminarily estimated that the R0 resection rate of CEMR for intermediate-sized (10-20 mm) colorectal polyps in the present study would be 50%. Next, an assumption was made that EMR-P could increase the R0 resection rate to 70%. The enrollment of 100 patients in each group provided 80% statistical power (α = 0.05) to detect a 20% difference between the groups. Considering a possibility of a dropout rate of 10%, it was planned to increase the sample size to 220 patients in total.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoints were analyzed according to the principle of intention-to-treat (ITT). The chisquared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables, while the Mann-Whitney U-test and the unpaired two-samplet-test were used for continuous variables. Additionally,logistic regression analysis was applied to calculate the odds ratios. All the analyses were two-sided,andPvalues < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. If the primary outcomes of a patient were missing or abnormal, the case data were discarded directly; if the secondary outcomes were missing or abnormal, the mean value of each group was used as a replacement. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS™ Statistics (version 21; Chicago, IL, United States) and R (version 4.1.2) software.

Histological examination

After resection, the specimens were immersed in 10% formalin and sent to the pathology department of each institution for histological evaluation. All the retrieved specimens were evaluated in terms of histologic types and involvement of the resection margin. Histological diagnosis of the lesion and involvement of the resection margin were evaluated according to the 2019 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System.

RESULTS

Participant flow

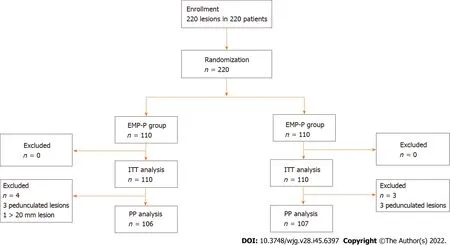

A total of 220 patients with 220 polyps were included in the study and were randomly assigned to two groups (the CEMR Group,n= 110; and the EMR-P Group,n= 110). These patients with 220 colorectal lesions were included in the ITT analysis for the primary endpoint. Three patients with pedunculated lesions in each group were excluded, while in the EMR-P group, one patient was excluded as the polyp was > 20 mm in size, leaving 213 patients (106 patients in the EMR-P group and 107 patients in the CEMR group) in the per-protocol analysis (PP analysis) (Figure 2).

Baseline data

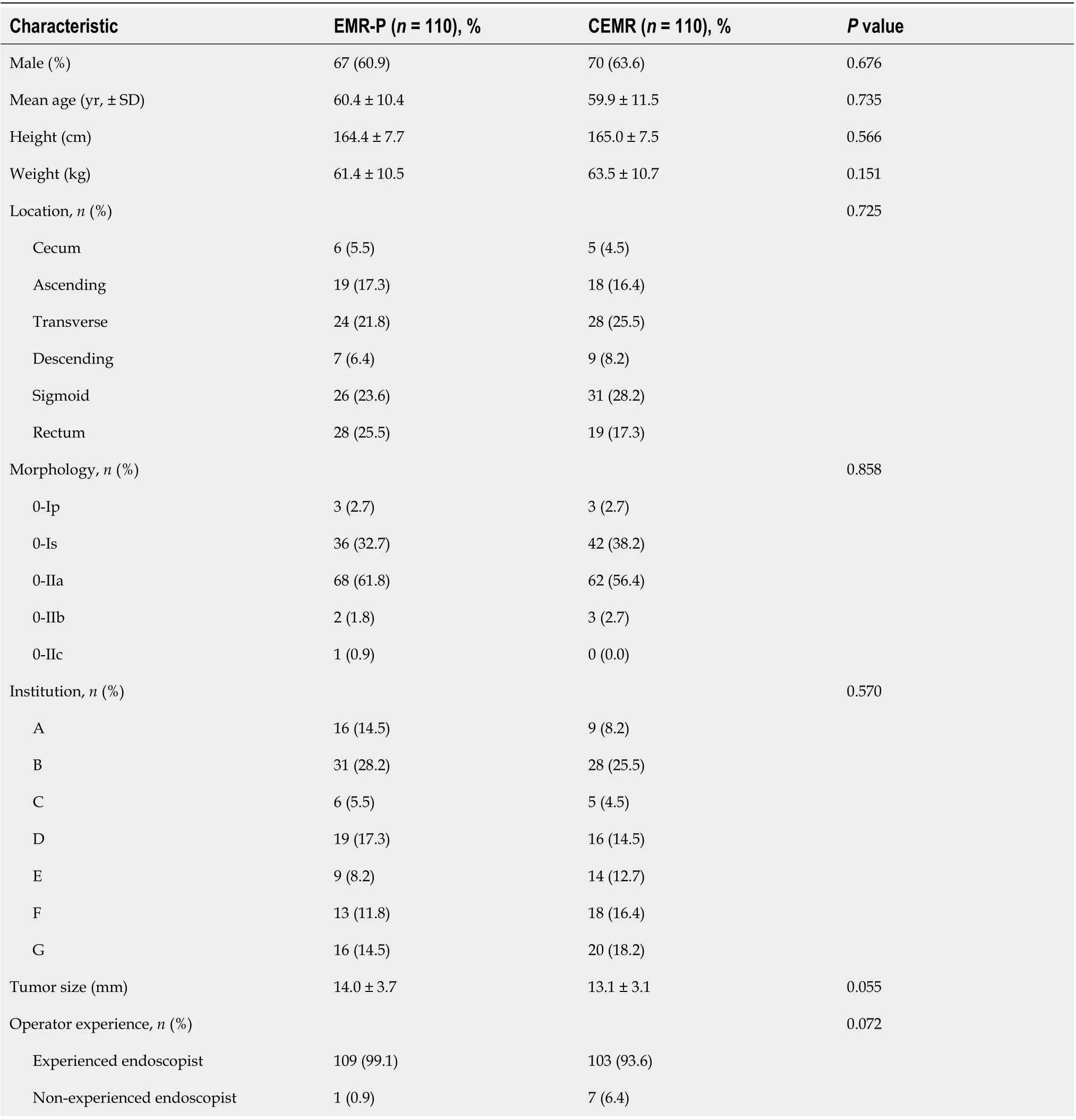

No significant difference was observed in age, sex, location or morphology of lesions, polyp size or endoscopist experience between the groups. In this study, 97.0% of patients in the EMR-P group and 99.0% of patients in the CEMR group received prophylactic clipping of resected wounds. All 220 patients were hospitalized for endoscopic treatment (Table 1).

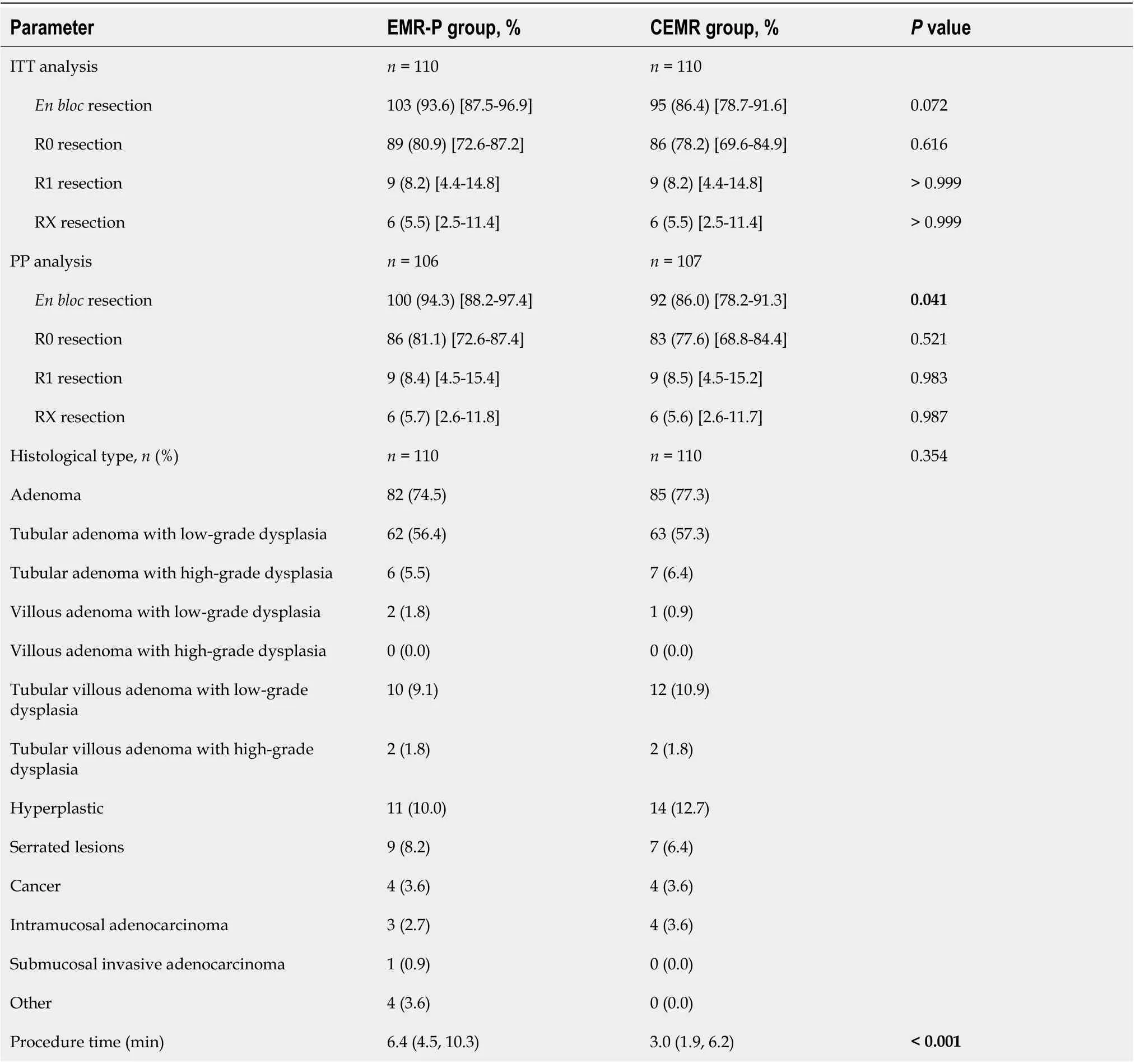

Procedure-related outcomes

Theen blocresection rate in the EMR-P group was higher than that in the CEMR group in both ITT and PP analyses (Table 1). However, only PP analysis showed a significant difference (94.3%vs86.0%;P=0.041). No significant difference was found in the R0, R1, and RX resection rates between the groups,though EMR-P showed a slightly but not significantly higher R0 resection rate. Histologically, most of the polyps in the two groups were adenomas (74.5% in the EMR-P group and 77.3% in the CEMR group), without a significant difference between the groups. The median operation times in the EMR-P and CEMR groups were 6.4 and 3.0 min (P< 0.001), respectively (Table 2).

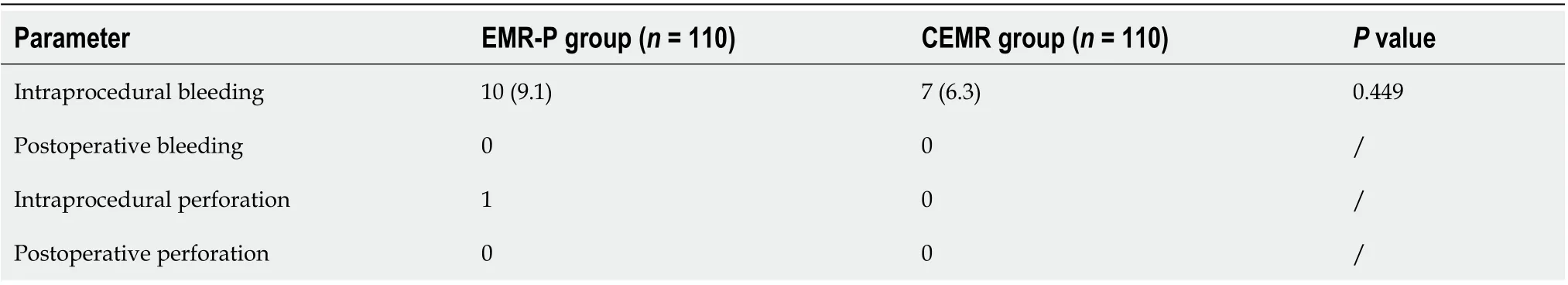

Adverse events

In the EMR-P group, four cases had bleeding during precutting while six cases had bleeding during the snaring and removal procedure; however, the occurrence of intraprocedural bleeding was not significantly different between the groups during the whole operation. One case of intraprocedural perforation occurred in the EMR-P group but did not result in a significant difference compared with the CEMR group (Table 3). These adverse events were successfully addressed by hemostatic clip placement. During the two-week follow-up period, no postprocedural bleeding or perforation occurred in either group, except for one patient who was required to undergo additional surgery due to the pathological diagnosis of rectal cancer with submucosal infiltration above 3500 µm.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the study population

Subset analysis

An exploratory subgroup analysis was conducted and found that in lesions > 15 mm, EMR-P was better foren blocresection (92.0%vs58.8%;P= 0.029). However, in lesions ≤ 15 mm, no significant difference was detected in theen blocresection rate (95.0%vs91.1%;P= 0.313). Overall, EMR-P showed a trend toward a higheren blocresection rate than CEMR, regardless of location, lesion size, institution, or operator experience (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

The present multicenter randomized controlled trial demonstrated that for medium-sized (10-20 mm)sessile colorectal polyps, theen blocresection rate of EMR-P (94.3%) was significantly higher than that of CEMR (86%), particularly in lesions > 15 mm. Additionally, compared with CEMR, EMR-P did not increase the incidence of adverse events.

Table 2 Procedure-related outcomes in this study

Although hot snare polypectomy (HSP) has been recommended by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinical Guidelines as a predominant technique to remove polyps sized 10-19 mm[4], incomplete resection remains an unavoidable issue. The Complete Adenoma Resection(“CARE”) study reported a high incomplete resection rate of 17.3% after HSP in polyps sized 10-20 mm[16]. Additionally, incompletely resected lesions may lead to 10%-30% of post-colonoscopy CRC[17].

Currently, EMR was proven to be superior to HSP in terms of the complete resection rate (89%vs73%;P= 0.02)[18], a finding also supported by another pooled study[19]. However, the increased lesion size was accompanied by an augmented piecemeal EMR resection rate[6], an important risk factor for local recurrence and metachronous neoplasia[20-23]. Notably, Okaet al[23] revealed that piecemeal resection and histologically positive margins were both risk factors for local recurrence in univariate analysis; however, only piecemeal resection was an independent risk factor in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Furthermore, as previously reported, piecemeal-resected lesions reduced the quality and reliability of histological evaluation[24], possibly leading to the inability to provide proper additional treatment and recommendations of appropriate surveillance intervals[4,25]. To improve theeffectiveness and safety of endoscopic colorectal lesion resection, several improved EMR techniques have been developed, such as EMR-P, underwater EMR (UEMR), anchored EMR, and cap-shaped EMR[4,26-28].

Table 3 Adverse events in this study

Figure 2 Flow diagram of the study. ITT: Intention-to-treat; PP: Per-protocol; EMR-P: Endoscopic mucosal resection-precutting; CEMR: Conventional endoscopic mucosal resection.

Of these, EMR-P was first described by Hiraoet al[29] in 1986 and has been reported as EMR with a small or circumferential incision or simplified ESD[12,30,31]. The application of this method for gastric neoplasms has also been reported[32-34]. In 2007, Repiciet al[35] first performed a single-center nonrandomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EMR-P (an it-knife was used for precutting) in theen blocresection of large colonic polyps. Although only 55.1% (16 of 29 patients) of the lesions (> 30 mm)achieveden blocresection, the authors suggested EMR-P was a promising technique.

Although some studies have confirmed the superiority of EMR-P to CEMR for large polyps (> 20 mm)[12,36], even noninferior to ESD[37,38], only one other study has directly compared the efficiency of EMR-P with CEMR in medium-sized polyps[11]. That study reported that EMR-P had a higher complete resection rate (87.8%vs67.3%;P< 0.001) anden blocresection rate (98.0%vs85.7%;P< 0.004)than CEMR. However, that study was retrospective with a small number of follow-up cases and an objective to analyze the efficacy of EMR-P for lesions that were challenging for standard EMR[11]. Thus,the guiding role of that study for clinical practice to tackle normal nonpedunculated lesions was limited.

In accordance with the results of PP analysis in the present study, EMR-P was superior to CEMR regarding theen blocresection rate (94.3%vs86%;P= 0.041), particularly in lesions > 15 mm (92.0%vs58.8%;P= 0.029). However, these significant differences were not found in the ITT analysis.

Although EMR-P also showed a higher R0 resection rate, no significant difference was found (ITT analysis: EMR-PvsEMR, 80.9%vs78.2%; PP analysis: EMR-PvsEMR, 81.1%vs77.6%). Notably, the results in the present study showed an overall higher R0 removal rate than in previous studies,regardless of the method applied. In a trial by Yamashinaet al[15], only a 50% R0 resection rate was achieved by CEMR for nonpedunculated colorectal polyps (median size: 13.5 mm); and UEMR, another alternative technique for medium-sized colorectal polyps, only resulted in a 75% R0 resection rate. For polyps sized 15-20 mm, Imaiet al[27] also indicated that only a 65.3% R0 resection rate was achieved by CEMR with added tip-in EMR in the whole group.

Figure 3 Subset analysis for en bloc resection. EMR-P: Endoscopic mucosal resection-precutting; CEMR: Conventional endoscopic mucosal resection.

Despite a lack of direct comparisons, these data implied that the similar R0 resection rates between the groups might be due to the high R0 removal rate by CEMR in the present study, leaving less room for improvement by EMR-P. Theoretically, EMR-P does have some advantages over the above two alternative treatments of CEMR. As it does not need to fill the entire lumen only with fluid, compared with UEMR, EMR-P saves a lot of time in deflating the lumen completely; moreover, its visual field during operation is less affected by poor intestinal preparation or intraprocedural bleeding. In comparison with tip-in EMR, circumferential incision of EMR-P allows the snare to be closer to the vertical margins of the lesions when snaring the polyps, which may be conducive to a better R0 resection rate.

Owing to the additional precutting step, EMR-P required a slightly longer total procedure time(EMR-PvsEMR: 6.4vs3.0 min, respectively;P< 0.001). However, considering the potential cost of retreatment caused by the higher risk of recurrence, spending some three more minutes in clinical operation, with no additional devices needed, seems more cost-effective. Additionally, despite including circumferential incision, more intraprocedural or postoperative bleeding cases in the EMR-P group were not observed. In the present study, only one patient in the EMR-P group experienced intraprocedural perforation, which was resolved through defect closure with endoscopic clips and antibiotic use.However, as most of the endoscopists were experienced, confirming the safety of EMR-P was challenging, particularly for endoscopists with less experience. This finding requires further clarification with follow-up research.

Theoretically, EMR-P is more difficult than CEMR but simpler than ESD, and EMR-P could also become an intermediate link to ESD training programs in the future. In the present study, the better performance of EMR-P was because of the circumferential incision. This additional step could facilitate the snare to be placed along the incision and then grasp and remove the lesions more reliably. However,during the snaring process, the benefit for vertical resection margins of EMR-P seems limited, likely explaining why it is difficult for all improved EMR techniques to achieve a 100% R0 resection rate.Additionally, circumferential incision may lead to unfavorable injected submucosal fluid maintenance,resulting in poor uplifting of mucosa and affecting the visual field. Fortunately, this weakness could be resolved by using thicker submucosal injectates to provide a sustained lift, such as succinylated gelatin,hydroxyethyl starch, or glycerol[4,39].

The present study has several limitations. First, the recurrence rate was not evaluated because followup colonoscopies were not performed. Thus, in accordance with the European guideline, surveillance colonoscopy three years after complete endoscopic resection is recommended[25]. Second, the singleblind study design may cause better outcomes of the new operation method, an inevitable problem of randomized controlled trials concerning endoscopy. Third, biopsy of the resected site after EMR has been recommended as the gold standard for evaluating the completeness of resection[40,41]. In the present study,en blocand histologically negative margins of the sample were used to define R0 resection, a strategy that might be prone to sampling error because marginal biopsies only represent part of the lesion margin.

CONCLUSION

The present randomized study revealed that EMR-P successfully achieved a > 90%en blocresection rate in 10-20 mm nonpedunculated polyps without increasing the incidence of adverse events. Although EMR-P may take slightly longer and result in a similar R0 resection rate than CEMR, its potential benefits are promising in clinical practice, particularly in lesions > 15 mm.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Zhang XQ, Xu L, and Yu CH designed the research; Zhang XQ, Sang JZ, Xu L, Mao XL, Li B,Zhu WL, and Yang XY participated in the operation; Zhang XQ and Xu L analyzed the data; Zhang XQ wrote the paper.

Institutional review board statement:The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University (No. 20191477); Ningbo First Hospital, Zhejiang(No. 2020-R013) and other participating institutions.

Clinical trial registration statement:This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. The registration identification number is NCT04191473.

Informed consent statement:All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data sharing statement:Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author at zhangxuequn@zju.edu.cn. Participants gave informed consent for data sharing.

CONSORT 2010 statement:The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 statement.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Xue-Qun Zhang 0000-0002-2330-6518; Lei Xu 0000-0001-6017-3745; Xin-Li Mao 0000-0003-4548-1867; Bo Li 0000-0001-6738-8087; Wan-Lin Zhu 0000-0002-4011-1632; Xiao-Yun Yang 0000-0002-9164-5573; Chao-Hui Yu 0000-0003-4842-3646.

S-Editor:Liu JH

L-Editor:Webster JR

P-Editor:Liu JH

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- COVID-19 drug-induced liver injury: A recent update of the literature

- Gastrointestinal microbiota: A predictor of COVID-19 severity?

- The mononuclear phagocyte system in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Deep learning based radiomics for gastrointestinal cancer diagnosis and treatment: A minireview

- Best therapy for the easiest to treat hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected patients

- Meta-analysis on the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in China