Virulent endocarditis due to Haemophilus parainfluenzae: A systematic review of the literature

2022-11-02AbdulbarilOlagunjuJakeMartinezDorothyKennyPhilipGideonFaroukMookadamSamuelUnzek

Abdulbaril Olagunju, Jake Martinez, Dorothy Kenny, Philip Gideon, Farouk Mookadam, Samuel Unzek

Abstract

Key Words: Haemophilus parainfluenzae; Infective endocarditis; Mitral valve; Vegetation

lNTRODUCTlON

Infective endocarditis (IE) remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. The incidence has increased from 5-7 cases per 100000 of the population in 2000 to 15 cases per 100000 person-years in 2011[1-3]. Common risk factors include an immunocompromised state, intravenous drug use (IVDU), underlying valvular disorders, prosthetic valves, and implanted cardiac devices[1-3]. The microbiology of IE is important and affects clinical presentation and prognosis[1-3]. Skin flora, includingStaphylococcus,EnterococcusandStreptococcusspp., are the most common causative organisms in IE, accounting for 80%-90% of cases, with a mortality rate as high as 30%[1-3].

Although less common, the oropharyngeal flora is also an important cause of IE, particularly the HACEK (Haemophilusspp.,Aggregatibacterspp.,Cardiobacteriumspp.,Eikenellaspp., andKingellaspp.) group[1,4-6]. This group has been identified in 1.5%-2% of all IE cases, with a mortality rate of 2%[4-6]. They are fastidious Gram-negative bacilli known for their slow growth in routine blood culture media, which may cause a delay in diagnosis[4,5]. Reported risk factors for the development of HACEK group IE include recent dental procedures and abnormal heart valves[4,5]. The most common organism implicated isAggregatibacterspp[4,6]; however, IE due toHaemophilus parainfluenzae(HPI) is gaining increasing attention in the literature. Here, we present an illustrative case of endocarditis in a healthy young man with no predisposing risk factors, and a systematic review of HPI IE cases reported in the literature within the last 20 years to characterize its clinical presentation, epidemiology and prognosis.

Illustrative case

A 25-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with a 2-mo history of worsening frontal headache and 1 wk of fever and watery diarrhea. Physical examination was significant for a fever of 39.1 °C, heart rate of 109 beats/min, blood pressure of 118/63 mmHg, and holosystolic murmur auscultated at the cardiac apex. Laboratory results were remarkable for white blood count (WBC) count of 12.9 K/L (normal: 4-11), hemoglobin 8.5 g/dL (normal: 13.5-17.0), mean corpuscular volume 77 fL (normal: 78-100), relative distribution width of 16.2% (normal: 11-15), procalcitonin 2.33 ng/mL (normal: 0.49), C-reactive protein 218 mg/L (normal: 4.9), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 56 mm/h (normal: 0-15). Intravenous (IV) vancomycin, ceftriaxone and acyclovir were initiated due to concern for meningitis. Chest radiograph and head computed tomography were negative for acute abnormalities. A lumbar puncture was performed, with cerebrospinal spinal fluid (CSF) analysis positive for WBC count of 231/mm3(normal: 0-5), with 67% neutrophils and 21% lymphocytes, glucose 51 mg/dL (normal: 40-70), and protein f 49.9 mg/dL (normal: 15-40). CSF herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction was negative, and acyclovir was discontinued.

Blood cultures on hospital day 4 showed Gram-negative rods, which speciated to HPI on hospital day 6. CSF cultures remained negative, and antibiotics were de-escalated to IV ceftriaxone for HPI bacteremia. Additionally, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy and subsequent biopsies were normal. Iron studies were significant for serum iron of 9 g/dL (normal: 40-190), transferrin 119 mg/dL (normal: 200-390), transferrin saturation 6% (normal: 15-50), total iron binding capacity 167.8 g/dL (normal: 250-435), and ferritin 1083 ng/mL (normal: 25-506).

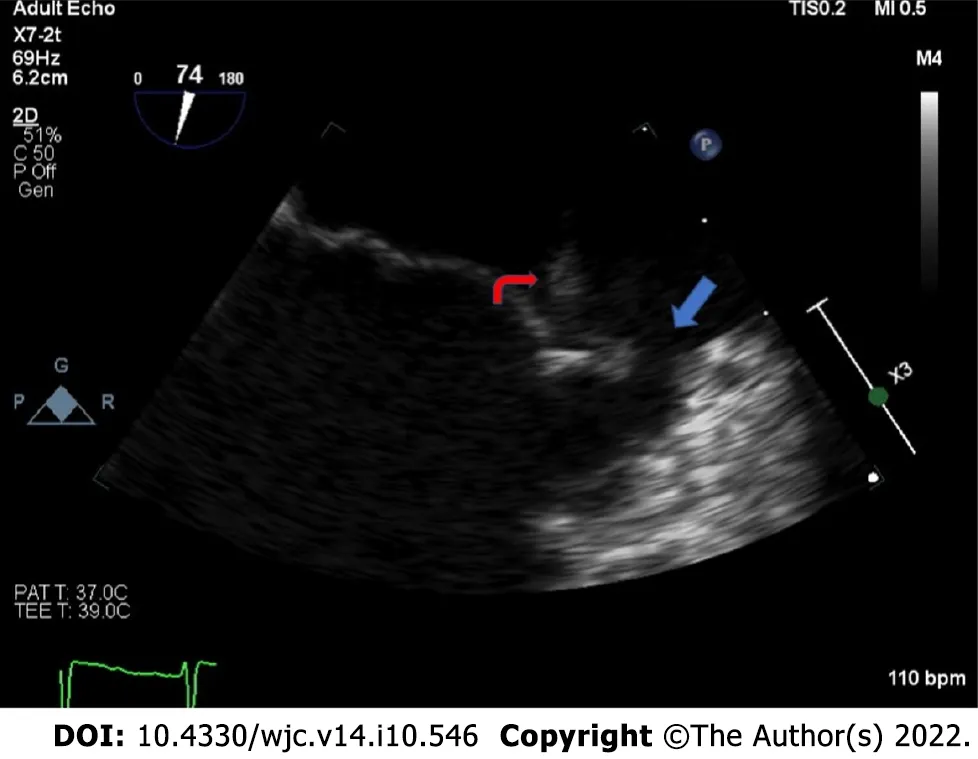

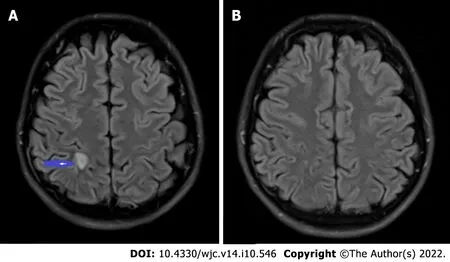

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) revealed two mobile echodensities on the atrial side of the mitral valve, consistent with vegetations on the A2 and P2 segments of the mitral leaflets (Figure 1), with an anterior leaflet perforation and a severe mitral regurgitation (Videos 1 and 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed a 1.0 0.5 cm ring enhancing lesion in the right parietal lobe with surrounding vasogenic edema, suggestive of an abscess secondary to septic emboli (Figure 2A). Repeat MRI brain at 4 wk revealed near resolution of the right parietal lobe lesion (Figure 2B). After completing 8 wk of ceftriaxone, he underwent mitral valve repair with edge-to-edge repair of A1 and P1 segments. Postoperative TEE revealed adequate A1 and P1 fusion. The postoperative course was complicated by left-sided proximal muscle weakness and paresthesia, which resolved within 48 h. He completed cardiac rehabilitation successfully and had no further complications.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Data sources and searches

Two authors (AO and DK) independently searched Medline, Pubmed, Scopus, Embase and Reference Citation Analysis from January 1, 2000 to March 30, 2022 using the following keywords:Haemophilus parainfluenzaeand infective endocarditis. An independent search was conducted by a qualified librarian using similar terms. Only articles published in English were included.

Article selection

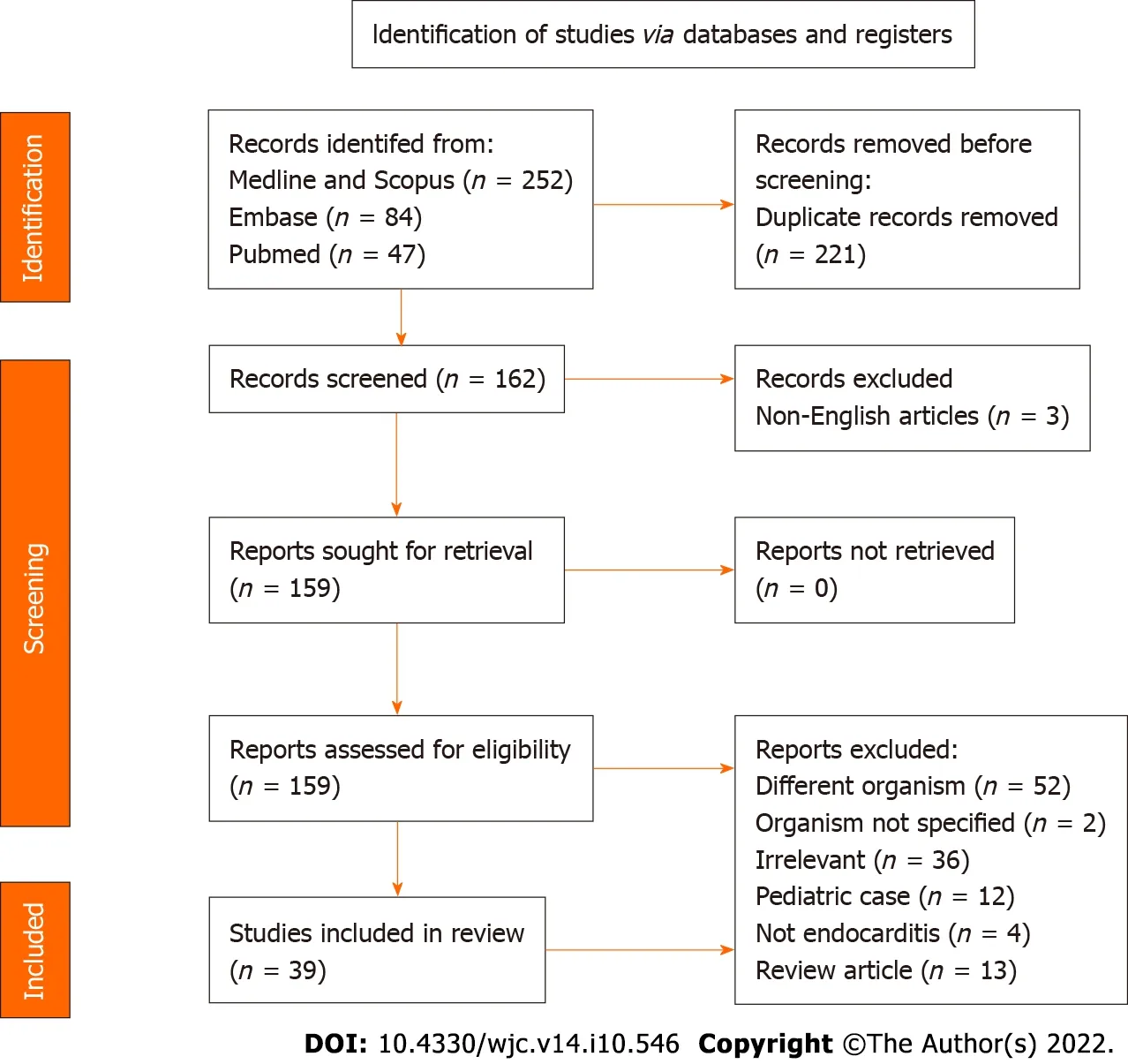

Inclusion criteria included IE due to HPI, patients aged > 18 years, positive blood or pathology specimens for HPI, and clinical and echocardiographic evidence of IE. Articles not meeting these criteria were excluded. The study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Metaanalysis (PRISMA)[7] (PRISMA 2009 Checklist).

Data extraction

Extracted data included patient demographics (age and gender), symptoms at initial presentation, comorbidities (prior valvular disorder, structural heart defects, recent dental, and gastrointestinal or genitourinary procedures), affected valves, severity of valvular damage, patient management, and complications.

Data analysis

We conducted a qualitative systematic analysis using descriptive statistics. A meta-analysis could not be performed due to the differences among individual cases and the small sample sizes (i.e.1 patient) included in the case reports.

RESULTS

Search results and article inclusion

Our initial search generated 383 articles. After excluding 221 duplicates, the remaining 162 articles were screened for inclusion (Figure 3). Of these, 39 articles[8-46] were systematically reviewed. The remaining articles were excluded because they were irrelevant to the topic (36 articles), discussing IE with organisms other than HPI (52 articles), review articles on HACEK organisms and IE (13 articles), pediatric case reports on HPI IE (12 articles), or not published in English (3 articles).

Patient characteristics

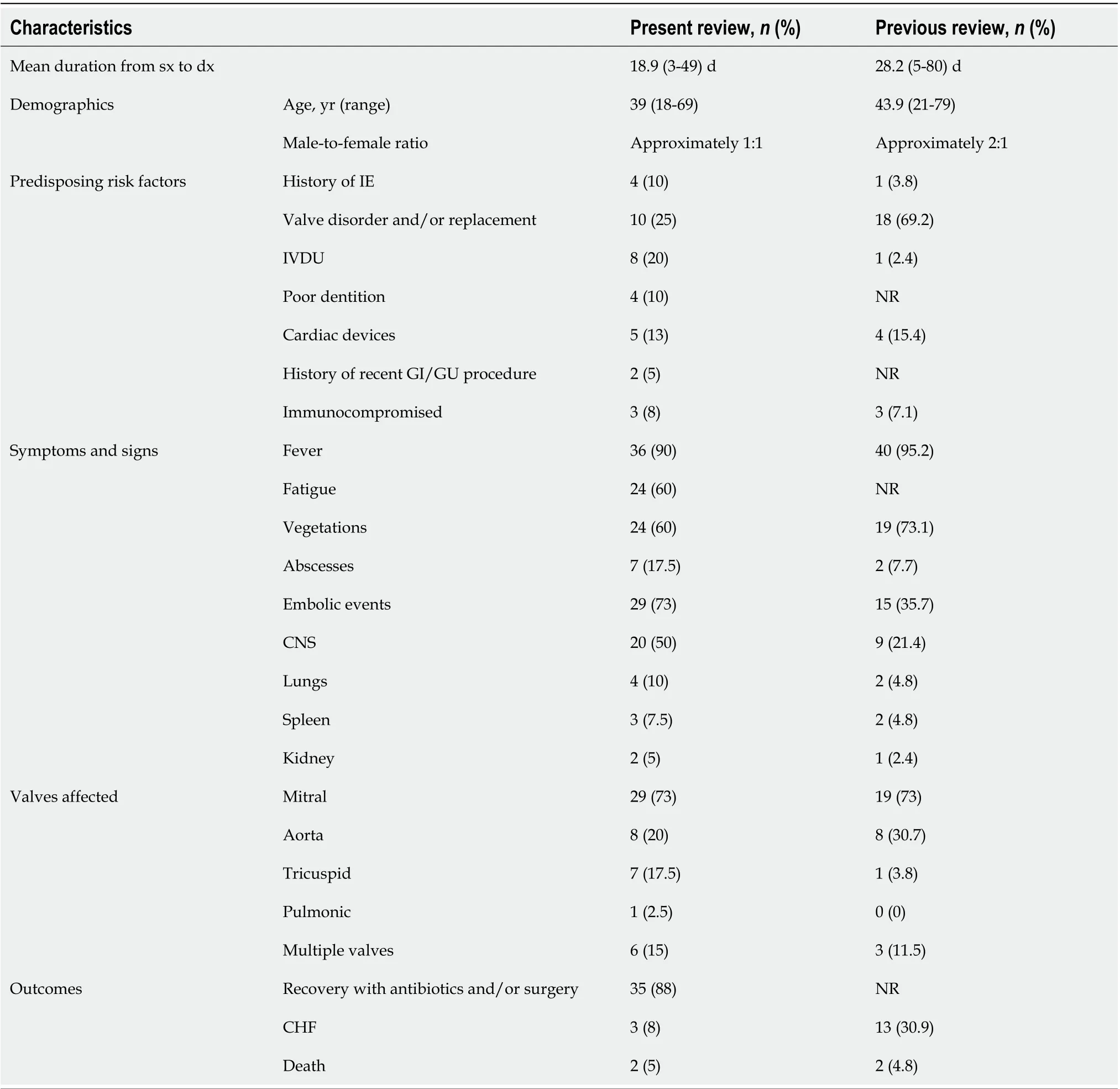

Age and gender: A total of 39 patients were identified. The mean age was 39 years, with a range of 18-69 years. There was a slight predominance towards men (52.5%).

Predisposing risk factors for IE: Approximately 10% of the patients reported a history of IE. About 17.5% had a history of valve replacement (4 with bioprosthetic valves, 2 with mechanical valves, and 1 with unspecified valve type). Twenty percent had mitral valve disorders (3 with mitral valve prolapse, 2 with rheumatic heart disease, and 1 with mitral regurgitation). Eighteen percent had aortic valve disorders (3 with bicuspid aortic valve and 3 with aortic stenosis). Current IVDU was reported in 17.5%. Approximately 10% had poor dentition. Thirteen percent had a history of pacemaker and implanted cardiac defibrillator placement. Two patients had a recent gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract procedure. Three patients were immunocompromised, 2 of which were pregnant (Table 1). Seven of the 39 patients had no predisposing risk factors.

Figure 1 Zoomed mid-esophageal view on transesophageal echocardiography, showing an echodensity attached to the A2 segment of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (red arrow) with evidence of leaflet perforation in the A1 segment (blue arrow).

Figure 2 Septic embolus in the brain. A: T2-weighted MRI brain showing a 1.0 cm × 0.5 cm ring enhancing lesion (blue arrow) in the right parietal lobe with central diffusion restriction and mild surrounding vasogenic edema; B: Repeat MRI brain with near complete resolution of the ring enhancing lesion. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Presenting symptoms and signs: The most common presenting symptom was fever, reported in most patients (36 patients), followed by fatigue (25 patients). Seven patients had shortness of breath, and four reported weight loss. Twenty-eight of 39 patients also presented with one or more manifestations of septic emboli, including embolic stroke (20 patients), septic pulmonary embolism (4 patients), renal emboli (2 patients), and splenic infarct (3 patients). Cutaneous manifestations were noted including Janeway lesions (3 patients), splinter hemorrhages (4 patients), petechiae or purpura (2 patients), or Osler nodes (1 patient) (Table 1).

Valve involvement: Valvular regurgitation was by far the most common abnormality; reported in 28 patients. Of these, 14 had severe regurgitation, eight had moderate regurgitation, and two had mild regurgitation. Mitral regurgitation and stenosis were reported in one case, and mitral valve prolapse was reported in one case. The mitral valve was the most common valve to be affected; noted in 28 patients. Eight patients had aortic valve involvement. The tricuspid valve was affected in seven patients, and only one patient had pulmonary valve involvement (Table 1).

Echocardiography: TTE was the main diagnostic modality, utilized in 36 (90%) patients, followed by TEE for confirmation in 33 patients. Valvular vegetations were reported in 23 patients, with anestimated mean size of 1.9 cm. Cardiac abscesses were reported in 17.5%, but abscess size was reported in only one of the cases as 1.6 1.8 cm. The abscess locations included the aortic root, mitral-aortic intervalvular fibrosa, near a prosthetic aortic valve, left ventricular endocardium, and myocardium. Three patients developed a fistulous connection between the atrium and ventricle. Valvular perforation was reported in 2 cases.

Table 1 Compares the characteristics of infective endocarditis caused by Haemophilus parainfluenzae in this systematic review with the review by Darras-Joly et al[58]

Treatment: The majority (28 patients) were treated both medically and surgically. Nine patients underwent valve repair, while six underwent replacement. Two patients underwent pacemaker removal. Eleven patients had unspecified surgical intervention. Sixty-two percent of patients were treated with ceftriaxone. Ten percent received other antibiotics including levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, cefotaxime and rifampin. The antibiotic therapy utilized in the remaining 28% of patients was not specified.

Outcome: Two patients reportedly developed congestive heart failure (CHF) and two patients died. The remaining 35 patients recovered adequately.

Figure 3 PRlSMA flow chart highlighting article search and selection.

DlSCUSSlON

HPI is a part of the oropharyngeal and genitourinary tract flora and has been implicated as a cause of opportunistic infections such as meningitis, IE, and septic arthritis[47]. It is a fastidious Gram-negative coccobacillus and belongs to the genusHaemophiluswhich consists of theH. influenzae,H. parainfluenzaeandH. ducreyigroups[47]. They require beta-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and/or heme to supplementin vitrogrowth[47]. An important differentiating feature of HPI is its ability to synthesize heme and hence does not require heme supplementation to grow[47].

The virulence of HPI is not well characterized[47,48]. In general, theH. parainfluenzaegroup has some degree of resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics, particularly penicillins[47,48]. Isolates have been identified that are multidrug resistant to tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones and macrolides[47]. The mechanisms behind this resistance are due to mutations in the penicillin-binding protein, Tet, DNA gyrase, topoisomerase, and 50s ribosomal protein genes[47,49]. The antibiotics with adequate minimum inhibitory concentration on HPI include levofloxacin, cefditoren, cefotaxime and cefpodoxime, although other antibiotics such as aminoglycosides and chloramphenicol may have adequate effect[50,51]. Culturing HPI involves addition of patients’ blood samples to a brain-heart infusion with 5% beef extract broth, which is incubated at 37 °C for up to 14 d[52]. Gram-negative coccobacilli are identifiedviaGram stain and inoculated onto a peptone-protease agar[52]. Paper discs containing NAD and heme are applied to the agar which incubates overnight[52]. HPI is then identified based on its sole reliance on the presence of NAD for growth[52]. Additionally, the 16S rRNA polymerase chain reaction and mass spectrometry are reliable means of differentiatingHemophilusspp. and the HACEK organisms without culturing[18].

In our review, the majority of patients had at least one predisposing risk factor for IE, such as a history of IE, an underlying valve disorder, a prosthetic or mechanical valve or a cardiac device, poor dentition, recent dental procedure within 2 wk, IVDU, or an immunocompromised state (including use of steroids or pregnancy). This is important for clinicians to recognize, as eradication or control of the predisposing factor may help prevent recurrent HPI infection.

The average duration between symptom onset and diagnosis was 18.9 d, and surgical intervention (due to the presence of large vegetations ~2 cm) was required in most of the patients (69%). These features highlight the indolent course of HPI IE and signify the need for prompt diagnosis, which may reduce the need for surgical intervention. The resolution of IE with cephalosporin, aminoglycoside and fluoroquinolone antibiotics suggests that the majority of HPI bacteria in the past 20 years are not multidrug resistant.

The risk of embolic events in IE is common withStaphylococcus aureus,Candidaspp., and HACEK organisms[51]. The reported incidence ranges between 28% and 66% forS. aureus, with central nervous system (CNS) embolism being the most common[53,54]. In this review, ~70% of embolic complications were in the CNS. This is notable as previously,Kingellaspp. appeared to have the highest rate of CNS embolism of all HACEK organisms, with a rate of 20%-30%[55]. Embolic events have been associated with worse prognosis in IE, with the risk proportional to vegetation size > 10 mm[53,54]. The indolent or subacute course of HPI IE may explain why the mortality remains lower compared to IE involving other organisms, despite significant vegetation size. The in-hospital mortality rates ofS. aureusandStreptococcusspp. IE are 20%-30% and 11%, respectively[53,56]. The mortality rate of HPI IE in this review was 5%. Of the HACEK organisms that cause IE in adults,Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans(a member of theAggregatibacterspp.) andCardiobacteriumspp. have the highest reported mortality rates of 18% and 10%, respectively[57,58]. While both are associated more with aortic valve endocarditis[57,58], HPI more commonly affects the mitral valve.

Our findings and the illustrative case show a temporal change in the epidemiology of HPI within 2000-2022. Compared to a review of 26 HPI endocarditis cases from 1984 to 1995 by Darras-Jolyet al[58], this review reported a younger mean age, similar rate of infection in both genders, shorter time to diagnosis, higher association with IVDU, higher rate of embolic events, and tricuspid and pulmonic valve involvement. The rate of mitral valve involvement has remained steady over the past three decades, while there has been a decrease in the rate of aortic valve involvement. Valvular vegetation rates and CHF incidence have decreased, while the mortality rate remained similar (Table 1). These findings might indicate the improvement in the diagnosis and treatment of HPI over the past three decades. However, the increased involvement of right-sided valves suggests an increase in its virulence and an association with the rising rate of IVDU. Notably, the review by Darras-Jolyet al[58] was not systematic because it was limited to cases in France. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review HPI IE to be published in the English language literature.

Our patient’s presentation of subacute IE highlights the typical features of HPI IE. It is indolent, has a predilection for the mitral valve, and is commonly associated with septic emboli involving the CNS. However, multiple features were present suggesting HPI may be more virulent in the current era, including the patient’s absence of risk factors, HPI induced leaflet perforation (which was not noted in our review), and valvular destruction requiring surgery.

Limitations

A noteworthy limitation of this review is that it did not account for unreported cases of HPI IE; therefore, we cannot ascertain an exact incidence and prevalence.

CONCLUSlON

This systematic review of reported adult HPI IE cases spanning the last two decades highlights the subacute course of HPI IE, its preference for the mitral valve, and favorable prognosis compared to IE caused by the other HACEK organisms,Staphylococcus, andStreptococcus. Clinicians should be attentive to its indolent course and the presence of predisposing risk factors in order to allow for timely management.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research results

This systematic review of 39 HPI IE cases in the English literature highlights the slight male predominance of the disease, the nonspecific presentation with constitutional symptoms, the predilection for the mitral valve, a high rate of central nervous system embolic events and a lower mortality rate compared to IE caused by microbes of the skin flora.

Research conclusions

HPI IE is an indolent disease that requires a high index of suspicion to diagnose and is associated with a favorable prognosis with timely intervention.

Research perspectives

We have illustrated a case and conducted a two-decade systematic review of the HPI IE cases published in the English language literature. In doing so, we have highlighted its indolent course, presentation and prognosis. We have also compared our findings with those of a review of HPI IE cases between 1984 and 1995; in doing so, we have enumerated some temporal changes in this disease entity. These include a younger mean age of presentation, identical rate of infection between males and females, improvement in diagnosis, a higher rate of embolic events and an increasing association with intravenous drug use.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Olagunju A and Mookadam F designed the research; Olagunju A, Kenny D, Martinez J, Gideon P, and Unzek S performed the research; Olagunju A, Kenny D and Mookadam F analyzed the data; Olagunju A, Kenny D, Martinez J and Mookadam F wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

PRlSMA 2009 Checklist statement:The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:United States

ORClD number:Abdulbaril Olagunju 0000-0001-9255-602X.

S-Editor:Liu JH

L-Editor:Kerr C

P-Editor:Liu JH

杂志排行

World Journal of Cardiology的其它文章

- Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: A rare but serious side effect of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors

- Is Takotsubo cardiomyopathy still looking for its own nosological identity?

- Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in cryoballoon ablation outcomes for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

- Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: A review of diagnostic methods and management strategies