Thawing k-essence dark energy in the PAge space

2022-10-22ZhiqiHuang

Zhiqi Huang

School of Physics and Astronomy,Sun Yat-sen University,2 Daxue Road,Tangjia,Zhuhai 519082,China CSST Science Center for the Guangdong-Hongkong-Macau Greater Bay Area,Sun Yat-sen University,2 Daxue Road,Tangjia,Zhuhai 519082,China

Abstract A broad class of dark energy models can be written in the form of k-essence,whose Lagrangian density is a two-variable function of a scalar field φ and its kinetic energy X ≡∂ μφ∂μφ.In the thawing scenario,the scalar field becomes dynamic only when the Hubble friction drops below its mass scale in the late Universe.Thawing k-essence dark energy models can be randomly sampled by generating the Taylor expansion coefficients of its Lagrangian density from random matrices[Huang Z 2021 Phys.Rev.D 104 103533].Reference[Huang Z 2021 Phys.Rev.D 104 103533]points out that the non-uniform distribution of the effective equation of state parameters(w0,wa)of the thawing k-essence model can be used to improve the statistics of model selection.The present work studies the statistics of thawing k-essence in a more general framework that is Parameterized by the Age of the Universe (PAge) [Huang Z 2020 Astrophys.J.Lett.892 L28].For fixed matter fraction Ωm,the random thawing k-essence models cluster in a narrow band in the PAge parameter space,providing a strong theoretical prior.We simulate cosmic shear power spectrum data for the Chinese Space Station Telescope optical survey,and compare the fisher forecast with and without the theoretical prior of thawing k-essence.For an optimal tomography binning scheme,the theoretical prior improves the figure of merit in PAge space by a factor of 3.3.

Keywords: dark energy,cosmological parameters,large-scale structure of universe

1.Introduction

Since the discovery of the accelerated expansion of the late Universe [3–5],it has been widely accepted that the current Universe is dominated by a dark energy component with negative pressure,whose microscopic nature is often interpreted as a cosmological constant (vacuum energy) that is conventionally denoted as Λ.Over the past two decades,the standard six-parameter Λ cold dark matter (ΛCDM) model has been confronted with a host of observational tests.The high-precision measurements of the temperature and polarization anisotropies of the cosmic microwave background(CMB)provide so far the most stringent constraints on the cosmological parameters [6,7],which agree well with many other observations such as the baryon acoustic oscillations [8–12],the Type Ia supernovae (SN) [13,14],the redshift-space distortion [15,16],and the cosmic chronometers (CC) [17–24].

Despite the observational success,the extraordinary smallness of the vacuum energy (fine-tuning problem) and the coincidence that Λ dominates the Universe only recently(coincidence problem)have,at least philosophically,disturbed cosmologists for decades [25].Moreover,as the accuracy of observations improves,the great observational success of the ΛCDM model is now challenged by a few anomalies.For instance,the Hubble constant H0inferred from CMB+ΛCDM is in~5σ tension with the distance-ladder measurements [26,27].Less significant challenges include a 3.4σ tension in the matter density fluctuation parameter S8between CMB and some cosmic shear data [28–30],a 2.8σ excess of lensing smearing in the CMB power spectra [7],and the lack of large-angle correlation in CMB temperature [31–34],etc.See [35]for a recent comprehensive review of the observational challenges to the ΛCDM model.

Given that Λ might not be the ultimate truth,we are well motivated to construct alternative dark energy models.A simple and in some sense also minimal construction is to introduce a scalar degree of freedom.Because high-order derivative theories typically suffer from the Ostrogradsky instability [36],it is often assumed that the Lagrangian density only depends on the scalar field value and its kinetic energyX=∂μφ∂μφ.This class of dark energy models,often dubbed as k-essence models,allows a variety of cosmological solutions with rich phenomena [37–73].In the early time when k-essence dark energy was first proposed,interests were more focused on using the so-called tracking solutions,where the field has attractor-like dynamics in the early Universe,to resolve the coincidence problem[74–77].It was understood later that the tracking k-essence models are not very successful solutions to the coincidence problem,because they require additional fine-tuning and superluminal fluctuations [78–80].Moreover,tracking models typically predict moderate deviation from Λ,which is more and more disfavored as the accuracy of observations improves [7,81].Alternatively,one can consider the so-called thawing k-essence[1,82–85],whose mass scale is close to or less than the current expansion rate of the Universe.In the thawing picture,the k-essence field is frozen by the large Hubble friction in the early Universe.Only at low redshift when the expansion rate drops below its mass scale,the field starts to roll.The lightness assumption (mass ≾H0) of thawing k-essence naturally leads to non-clustering dark energy whose perturbations are suppressed on sub-horizon scales.There do exist,however,models of dark energy with noticeable subhorizon perturbations[86–91].In the present work we do not discuss clustering dark energy models,as they typically need to be treated in a one-by-one manner.

The assumption of a thawing scenario significantly reduces the model complexity.Generating the Taylor expansion coefficients of L(φ,X) from random matrices [1],shows that a majority of k-essence dark energy models follows an approximate consistency relationwa≈(1+w0),where Ωmis the present matter density fraction and w0,waare the Chevallier–Polarski–Linder (CPL) parameters for dark energy equation of state(EOS)[92,93].The consistency relation can be understood as follows.Due to the thawing nature,the present rolling speed of the scalar field,which is characterized by 1+w0,is typically correlated to the acceleration of late-time rolling,which is characterized by wa.

The approximate consistency relation can be combined with observational data to improve the constraining power of cosmological data,which is often measured with the so-called figure of merit in marginalized w0–waspace.For a concrete model,however,the dark EOS does not exactly follow the CPL form w(a)=w0+wa(1-a),where a denotes the scale factor.The parameters w0,watherefore only have an approximate meaning and should be considered as an effective description of dark energy at low redshift.In the present work,we consider another effective description of dark energy with the Parameterization based on cosmic Age (PAge) [2,94–99].Compared to the CPL w0–waeffective description,PAge does not suffer from a strong parameter degeneracy that is commonly found between w0and wa.Thus,the parameter space of PAge is more compact.The Figure of Merit for the parameterization based on cosmic Age,which we abbreviate as FROMAge to show our French taste,is an equally good,if not better,indicator of the constraining power of cosmological data.

The article is organized as follows.section 2 briefly reviews PAge cosmology.In section 3,we use the numerical tool developed in [1]to generate an ensemble of random thawing k-essence dark energy models,which are then mapped into PAge parameter space.In section 4,we take a future cosmic shear survey as a working example to quantify by how much the thawing k-essence prior may improve the constraining power of cosmological data section 5 concludes.Throughout the paper we work with natural units c=ħ=1 and a spatially-flat Universe with Friedmann–Lemai^tre–Robertson–Walker background.The cosmological time and Hubble parameter are denoted as t and H,respectively.The dark EOS is denoted as w,which in general is a function of redshift z.A dot represents derivative with respect to the cosmological time.The current scale factor is normalized to unity.The Hubble constant is denoted as H0=100h km s-1Mpc-1.The square root of the cosmic variance of the mean density in a sphere with radius 8h-1Mpc is denoted as σ8,which then defines theparameter.

2.PAge cosmology

At redshift z ≾100,where the radiation component can be ignored,PAge approximates the expansion history of the Universe with the following ansatz [2]

where page=H0t0is the age of the Universe measured in units ofH0-1and η<1 is a phenomenological parameter approximately describing the deviation from an Einstein de-Sitter Universe.

Although it may seem like a casual assumption,the PAge ansatz(1)makes use of quite a few physical conditions.First of all,the parameters H0and pageare physical quantities that can be directly computed for any given physical model.Secondly,ansatz(1)automatically sets the matter-dominated behavior at a high redshift (l imt→0+Ht=).Finally,ansatz(1) guarantees that the expansion rate H monotonically decreases as the Universe expands.Thanks to these physically motivated features,PAge well approximates much dark energy and modified gravity models [2,94],and performs better than many other phenomenological approaches,such as the oft-used polynomial approximation [100].

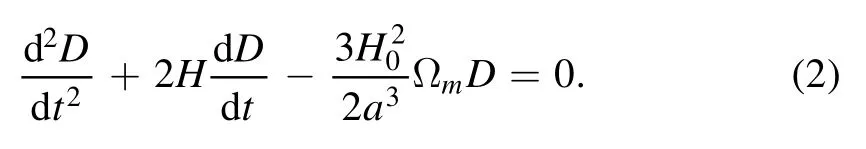

At the background level,whenH0-1is treated as a time unit,the expansion history is determined by ppageand η,and therefore Ωmis not a parameter in PAge.While perturbation calculation is needed for the simulation of the cosmic shear data,we add Ωmto the PAge framework and employ the following linear growth equation

Figure 1.The accuracy of PAge approximation.Left panel:EOS w(z)of a few randomly sampled k-essence dark energy models;right panel:relative error in luminosity distances when the models in the left panel are approximated with PAge.In all cases Ωm is fixed to 0.3.

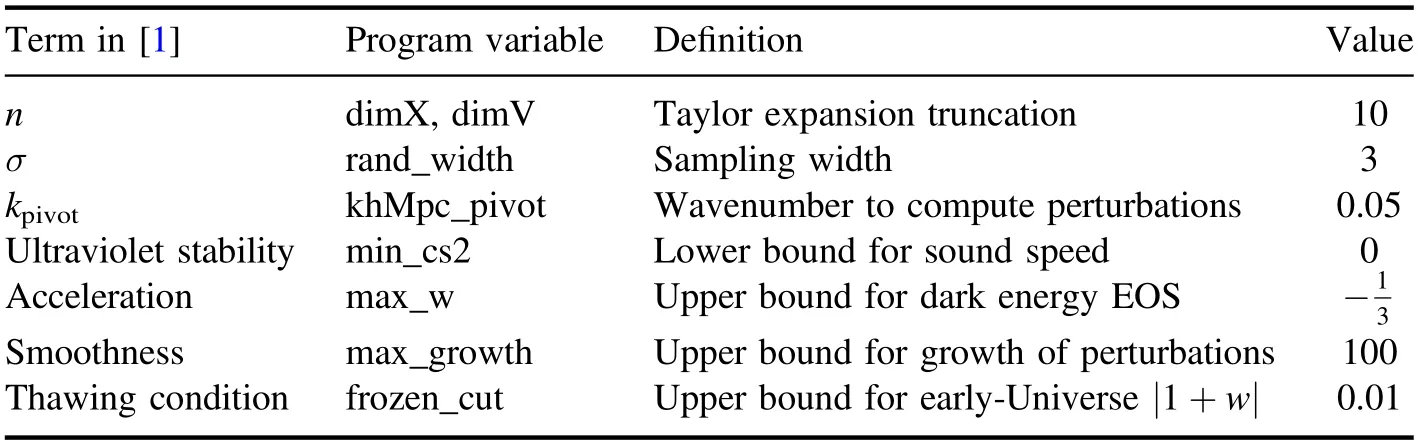

Table 1.k-essence generator program settings.

The assumption that goes into the above equation is that dark energy perturbations at sub-horizon and linear scales can be ignored.

Although more sophisticated approaches exist,for simplicity and to show the robustness of PAge approximation,we follow the simple method in[2]to map dark energy models to PAge space.The η parameter is calculated using the deceleration parameterq≡-evaluated at redshift zero.

3.Thawing k-essence in PAge space

We use the numerical tool developed in [1],which has been made publicly available at http://zhiqihuang.top/codes/scan_kessence.tar.gz,to generate random k-essence dark energy models.The program settings are shown in table 1.See also[1]for more detailed documentation of the program parameters.It has been shown in [1],and also tested in the present work,that increasing the truncation order and the sampling width do not change the distribution of sampled trajectories much.This is because models with increasing complexity typically violate the thawing condition (|1+w|≪1 in the early Universe),the acceleration assumption (w<-)or the smoothness assumption (growth of density contrast ≾102),and thus are rejected by the program.

We generate 41 000 random k-essence dark energy models for a flat prior Ωm∈[0.25,0.35].The models are then mapped into PAge space to generate a joint distribution of(ppage,η,Ωm),which we refer to as the thawing k-essence prior.The mapping procedure comes with a tiny accuracy loss in predictions of cosmological observables.In the left panel of figure 1,we show a few k-essence dark energy EOS trajectories with different colors.The relative difference between the luminosity distances predicted from each model and that from its PAge approximation is shown with the same color in the right panel.The errors are typically at a sub-percent level.These tiny errors may be relevant for future cosmological surveys and can be corrected with a more sophisticated approach [97].We nevertheless work in the original simple PAge framework that is easier to interpret,because the main purpose of the present work is to study the impact of the thawing k-essence prior,rather than the accuracy of PAge approximation.

Due to parameter degeneracy,if the dark energy EOS is a free function of redshift,an exact reconstruction of Ωmfrom the expansion history of the Universe is impossible.Since the Lagrangian density L(φ,X) is a free function,the EOS of k-essence is almost free,too.However,when the aforementioned physical assumptions are applied,the EOS of thawing k-essence dark energy is not free in a statistical sense.In figure 2 we compare the mapped (page,η) samples for Ωm=0.25,0.3 and 0.35,respectively.It is evident that one can obtain a statistical constraint on Ωmfrom the evolution history that is determined by (page,η).This is a non-trivial result.For a cosmic shear survey,the additional information on Ωmcan break the strong degeneracy between Ωmand σ8and lead to a better reconstruction of low-redshift physics.To make the idea more concrete,in the next section we take a future cosmic shear survey as a working example to quantify the impact of the thawing k-essence prior.

Figure 2.Randomly sampled k-essence dark energy models mapped into the PAge space.

4.Cosmic shear fisher forecast

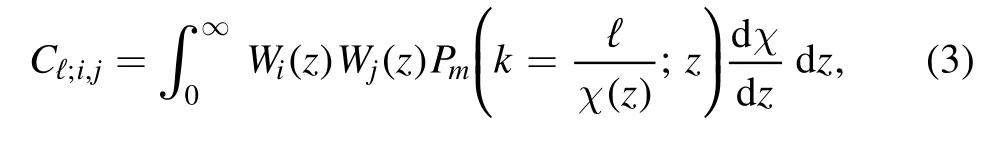

To make the analysis simple and easy to interpret,we only consider the statistics of the convergence field.The angular power spectrum between the redshift bins i and j is given by the Limber approximation [101–104]

where the comoving angular diameter distance in a spatially flat Universe is given by

The nonlinear matter power spectrum at redshift z,Pm(k;z)where k denotes the wavenumber,is calculated with the Bardeen–Bond–Kaiser–Szalay fitting formula [105]and the halo-fit formula[106,107].The weight function in the ith binz∈[zimin,zimax]is given by

Figure 3.Simulated cosmic shear data with two redshift bins: z ∈[0,1](bin 0) and z ∈[1,3](bin 1).

Table 2.Redshift binning schemes.

The total number density of observed galaxies is then the sum ntotal=∑ini.

The observed convergence power spectrum with shot noise is modeled as

where δijis the Kronecker delta function and σ∈is the root mean square of the Galaxy intrinsic ellipticity.

For the angular scales we take a conservative multipole range 10≤ℓ≤2500.Due to the central limit theorem,the integrated convergence fields over this range are quite close to Gaussian [108–110],and therefore can be written as

where fskyis the fraction of sky that is observed.

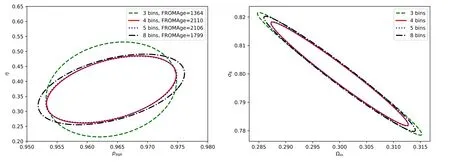

Figure 4.Fisher forecast for different numbers of tomography bins.Photometric redshift error is taken to be 0.03(1+z).

If the cosmological redshifts of galaxies were all perfectly known,an optimal analysis would be done within the limit of taking infinitely many redshift bins.In practice,however,the redshift of a photometric survey has a large uncertainty,which in our simulation is assumed to be σ(z)=0.03(1+z).Conventionally when doing a Fisher forecast,the photo-z errors are treated by marginalizing some shift parameters and spreading parameters [104,111],and the result inevitably depends on many assumptions that are difficult to justify at the stage of forecasting.To make the result robust and easy to interpret,we take a very conservative approach by simply discarding the galaxies samples around the edges of the redshift bins.More concretely,we cut each redshift bin [zimin,zimax]to a smaller one [zimin+σ(zimin),zimax-σ(zimin)].This approach is conservative because we have assumed almost no knowledge about the photo-z error distribution function,which in realistic surveys will be known to some extent.

We have assumed that many other subtle effects such as the intrinsic alignment contamination [112],catastrophic redshift outliers[113],and the super-sample covariance[114]can be well calibrated.The reader is referred to [113,115–119]for a more detailed discussion about the calibration of these systematics.

In our simulation we assume a galaxy intrinsic ellipticity σ∈=0.3,a galaxy distribution n(z)∝z2e-z/0.3that is normalized byntotal=28 arcmin-2,and a sky coverage fsky=0.424.The configuration roughly corresponds to the optical survey that will be carried out by the Chinese Space Station Telescope[120].In figure 3,we show the simulatedCℓobsand their standard deviations for two redshift bins and thirty ℓ-bins.

We employ the Fisher forecast approach to compute the constraining power on the five dimensional parameter vector:θ=(page,η,h,Ωm,σ8).The Fisher matrix is given by

where the data vector d is the collection of the observed power spectraand Cov is the covariance matrix given in equation(8).The covariance of the parameter vector is estimated with the inverse of the Fisher matrix,Cov (θI,θJ) ≈ (F-1)IJ.

We first study the dependence of the result on the number of redshift bins by comparing four binning schemes listed in table 2.

The marginalized 68.3% confidence-level constraints for(page,η),as well as the FROMAges for the four binning schemes are shown in the left panel of figure 4.As we increase the number of redshift bins,the constraining power(FROMAge)increases at the beginning,and then drops when the photometric redshift error comes into play.A similar tendency is also observed for the other cosmological parameters,such as the (σ8,Ωm) combination presented in the right panel of figure 4.

Finally,we apply the thawing k-essence prior in the Fisher analysis.We first bin and interpolate a prior likelihood P(Ωm,page,η) from the random samples obtained in the previous section.A full likelihood is obtained by multiplying the data likelihood by the prior likelihood.We run Monte Carlo Markov Chain simulations to obtain the posterior covariance matrix,which is plotted in figure 5 against the original Fisher forecast without thawing k-essence prior.For(page,η)the thawing k-essence prior improves the FROMAge by a factor of 3.3.A similar improvement is found for(σ8,Ωm),too.

5.Conclusions

We have shown,with a simple Fisher forecast of future cosmic shear survey,that a reasonable theoretical prior of dark energy can significantly improve the constraining power of the data.This raises the question of whether it is proper to judge the future dark energy surveys with a blind figure of merit without any theoretical prejudice.After all,the history of science has proven that theoretical prejudice is sometimes beneficial.

Figure 5.Fisher forecast of the 1σ and 2σ constraints on cosmological parameters,with and without thawing k-essence prior.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant No.12 073 088,National SKA Program of China No.2020SKA0110402,National key R&D Program of China (Grant No.2020YFC2201600),and Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (Grant No.2019B030302001).

ORCID iDs

杂志排行

Communications in Theoretical Physics的其它文章

- Preface

- Phase behaviors of ionic liquids attributed to the dual ionic and organic nature

- Chaotic shadows of black holes: a short review

- QCD at finite temperature and density within the fRG approach: an overview

- The Gamow shell model with realistic interactions: a theoretical framework for ab initio nuclear structure at drip-lines

- Effects of the tensor force on low-energy heavy-ion fusion reactions: a mini review