The effect of climate factors on the size of forest wildfires (case study: Prague-East district, Czech Republic)

2022-09-08ZohrehMohammadiPeterLohmanderJanKaparRomanBerJaroslavHoluRobertMaru

Zohreh Mohammadi·Peter Lohmander ·Jan Kašpar·Roman Berčák·Jaroslav Holuša ·Robert Marušák

Abstract This paper presents a new approach to identifying the climate variables that influence the size of the area burned by forest wildfires.Multiple linear regression was used in combination with nonlinear variable transformations to determine relevant nonlinear forest wildfire size functions.Data from the Prague-East District of the Czech Republic was used for model derivation.Individual burned forest area was hypothesized as a function of water vapor pressure, air temperature and wind speed.Wind speed was added to enhance predictions of the size of forest wildfires, and further improvements to the utility of prediction methods were added to the regression equation.The results show that if the air temperature increases, it may contain less water and the fuel will become drier.The size of the burned area then increases.If the relative humidity in the air increases and the wind speed decreases, the size of the burned area is reduced.Our model suggests that changes in the climate factors caused by ongoing climate change could cause significant changes in the size of wildfire in forests.

Keywords Climatic variables·Burned forest area ·Climate change·Multiple linear regression

Introduction

Climate change is a challenge for forestry because of the direct effects it has on forest ecosystems, and the lengthy period between making decisions and seeing the results(Yousefpour et al.2017).Increasing air temperature and changing precipitation regimes lead to climate change,including changes to snowfall amounts, and the timing and inter-annual variability of rainfall (IPCC 2013).Evidence of climate change and its effects on European forests grows stronger every year.Human activities, including fertilizer production, fossil fuel combustion, and land-use change,are significantly increasing the concentration of CO2and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (Rustad et al.2012).Another important factor is that summer warming may be more closely linked to higher temperatures than to regular warming on warm days, while much of the warming in winter is related to higher temperatures on cold days(Kjellstro et al.2011).Global warming has dried out fuels and increased the length of fire seasons across the globe(Jolly et al.2015), and is particularly significant in forested ecosystems with abundant fuel (Aragão et al.2018).In the Czech Republic, climate change manifests as weather events such as more frequent torrential rains, longer droughts,heat waves, and warmer and wetter winters with unusual amounts of snow (Czech Hydrometeorological Institute 2019).According to the Institute, a rise in the length of drought periods and air temperatures by the end of the century is predicted for the Europe.Climate change is a key factor in increasing the size of wildfires in European countries (De Rigo et al.2017).Several studies have confirmed that meteorological variables can be used to predict wildfire activity.For instance, Koutsias et al.( 2013) assessed the relationship between forest fire activity and meteorological parameters, and looked for temporal patterns and trends in historical records to determine any correlation between meteorological parameters and fire occurrence in the eastern Mediterranean region.Turco et al.( 2013) analyzed the effects ofinterannual climate variability on summer forest wildfires in Catalonia.They indicated that the interannual variability correlated closely with summer precipitation and summer maximum temperature.Gudmundsson et al.( 2014)predicted wildfire activity as a function of meteorological drought in southern Europe.Trigo et al.( 2016) analyzed the relationships between burned area on a monthly basis with both long-term previous seasonal climatological conditions and short-term synoptic forcing, using correlation and regression analysis.The short-term synoptic forcing was obtained based on synoptic weather patterns.The longterm previous seasonal climatological conditions also were obtained based on air temperature and precipitation for between two and seven months before the peak wildfire season.Turco et al.( 2017) analyzed and modeled the effects of coincident drought and antecedent wet conditions, (a proxy for the climatic factor influencing total fuel and fine fuel structure) on the summer burned area across all eco-regions in Mediterranean Europe.Lohmander ( 2020) investigated the average relative burned area as a function of average temperature and other factors in 29 countries.Studies also show that wildfire activity is expected to increase across the Mediterranean Basin due to climate change (Turco et al.2018; Dupuy et al.2020).However, prediction of the effects that climate and weather conditions will have on wildfire activity remains largely uninvestigated (Ruffault et al.2020).

Preventing wildfires is crucially important, since controlling wildfire is both costly and dangerous (San Miguel-Ayanz et al.2003).More monitoring and prediction of the wildfire changes is required therefore, to estimate the effects of climate factors on forest wildfire activity, and action is required to prevent negative consequences (Levina and Tirpak 2006).Various methods have been used to evaluate and model wildfire activity on large spatial or regional scales,such as artificial neural networks (Calp and Kose 2020),weight of evidence modeling (Hong et al.2017) and Bayesian belief network analysis (Dlamini 2010).Chang et al.( 2013) predicted forest wildfire ignition in Heilongjiang province, China, using the logistic regression method and climatic and meteorological variables.They demonstrated that wildfire ignition could be predicted through logistic regression.In Brazil, Eugenio et al.( 2016) applied multiple linear regression (MLR) using air temperature (a dependent variable) and altitude (an independent variable) to develop a forest wildfire risk map.Viganó et al.( 2018) used the concepts of MLR and autoregressive integrated moving average(ARIMA) to develop mathematical modeling to predict the number of forest wildfires in the Pantanal by evaluating the influence of climatic factors correlated with the probability of a combustion process occurring.For the present research,the analysis includes estimations of nonlinear, multi-dimensional wildfire size functions.With these functions, changes in a wildfire size can be determined when a number of conditions change simultaneously.It is hypothesized that the rise of wind speed cubed and air temperature and reduced air humidity simultaneously leads to increased size of the individual burned area.Earlier models have mostly been constructed with only one explanatory variable and have focused on other aspects of fire activity.To our knowledge,no previous research has addressed this issue in the Czech Republic.In other words, this study aims to identify the relationship between climate data and the size of forest wildfires,and to offer a new approach for predicting an individual burned area using these variables for forest management.

Material and methods

Study area

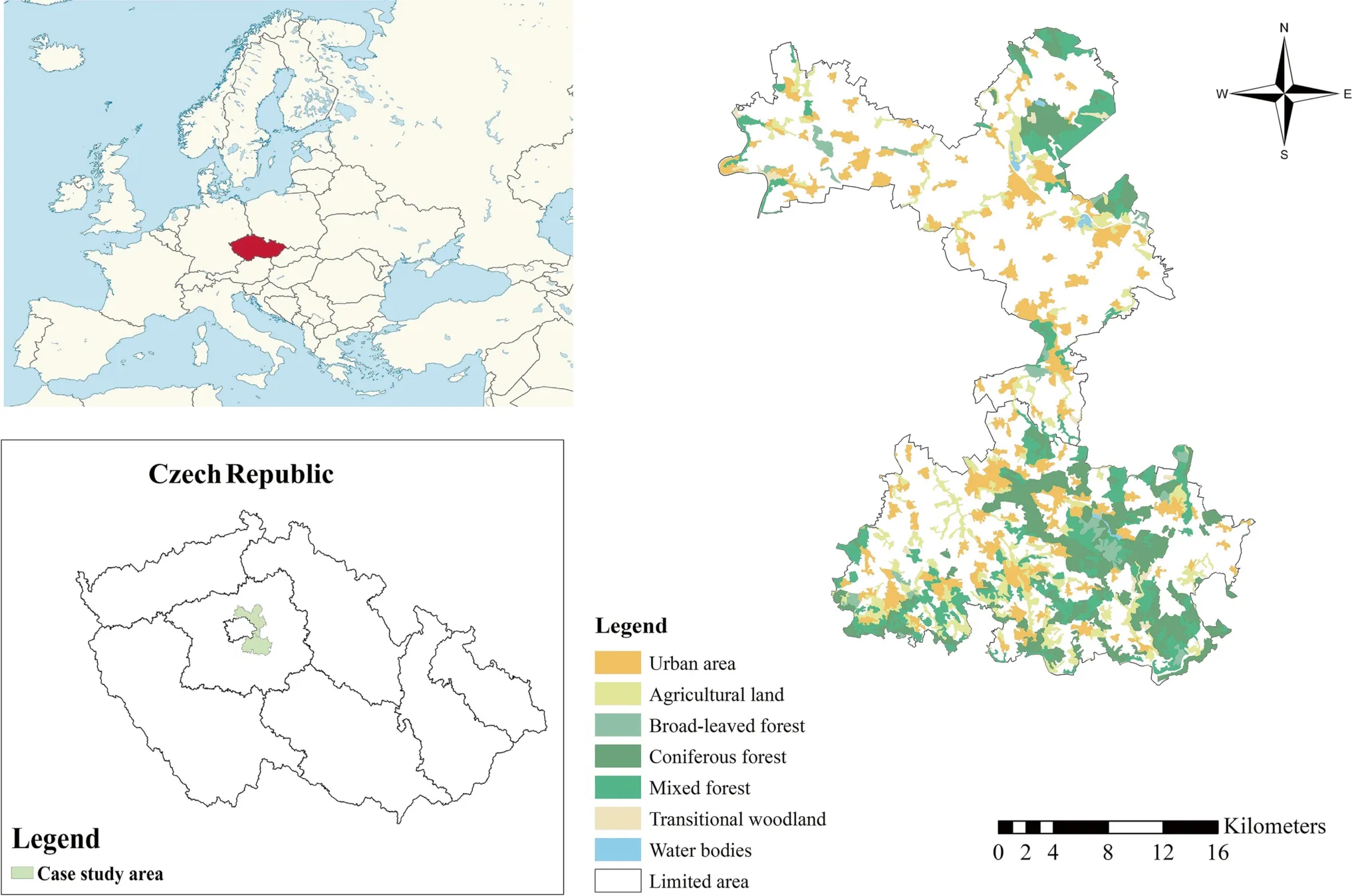

The research was carried out in the Prague-East District of the Central Bohemian Region, latitude 50°6′0″ N and longitude 14°42′0″ E.This district is 754.9 km2and the most populous in the region.Agricultural land occupies 63.2%and forests 22.5% of the region.Approximately 93% of the forested area is dominated by coniferous and mixed forests,and 7% by broad-leaved forests (Czech Statistical Office 2019) (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Study area and land cover types in the Prague-East District of the Czech Republic

Variables used

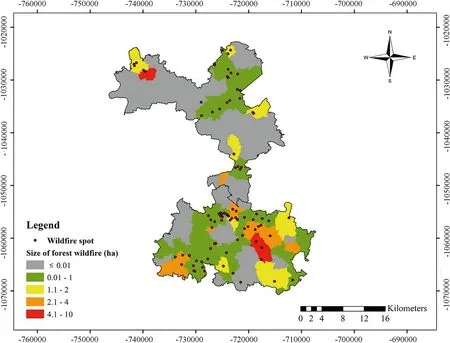

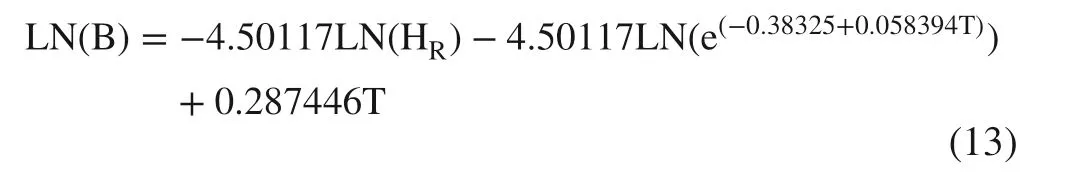

Burned area data were used to create our dependent variable and were taken from the database of the Czech Republic Wildfire Rescue Service for the study period July 2006 to November 2015 (Holuša et al.2018) (Fig.2).The data included date, location, area burnt, and number of wildfires.The total number of wildfire records in the database was 115.Climate data for each wildfire, including temperature at midday (°C), relative humidity on the day of the wildfire and three days before (%), and the average wind speed (km h-1) was acquired from the station nearest the wildfire location (Czech Republic Hydrometeorological Institute 2019).

Fig.2 Forest wildfire size and location in the period 2006–2015

Feature selection

To predict the size of forest wildfire, it was necessary to identify the effective parameters that influence wildfire size.The modeling began by considering the theory of the size of an individual burned area studied by Lohmander ( 2021) (Eq.1).

Where B (m2) is the size of the burned area after a wildfire.The individual burned area is a function of water vapor pressure (kPa); T, air temperature (°C); W, wind speed (km.h-1);F, level of fuel treatment (index); L, capacity of the local wildfire brigade (index); D, distance between parallel roads in the area, (hm=100 m); and, ‘other factors’φ.

We investigated whether a theoretically intelligible and reliable mathematical model could be defined, evaluated and empirically examined.The model should anticipate the individual burned area as a function of the influencing factors.These factors should be formulated from the empirical data available.

The use of MLR analysis was favored here to determine the climate variables that influence wildfire size.In our first analysis, it was assumed that φ remains more or less constant.Hence, the following function was obtained (Eq.2):

Estimated individual burned area function B=B (P, T)

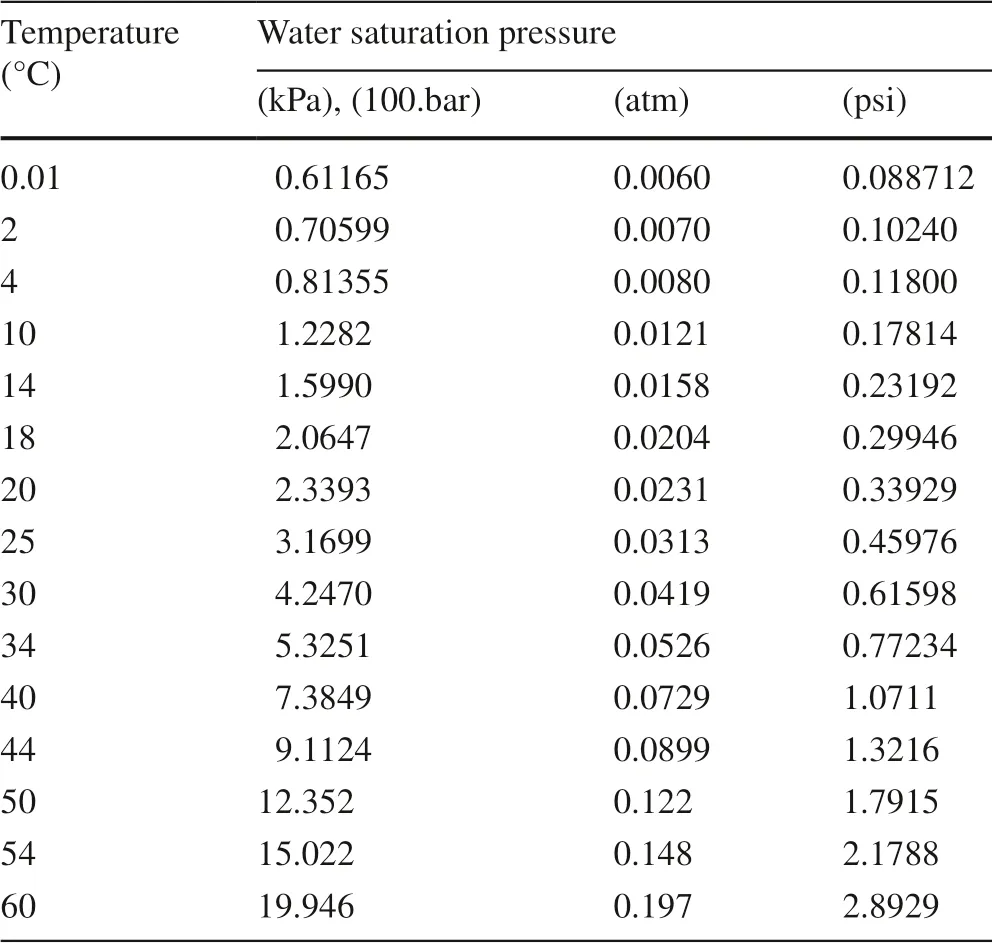

The water vapor pressure first had to be evaluated.With access to available water source(s), water vapor pressure converges over time on the saturated water vapor pressure.This is a function of the temperature.Temperature and saturated water vapor pressure data were collected (Engineering Toolbox 2004) (Table 1) and regression analysis carried out using Excel software.

Table 1 Saturation water vapor pressure (temperatures in °C), and pressure (kilopascals, kPa), bars, atmospheres (atm) and pounds per square inch (psi)

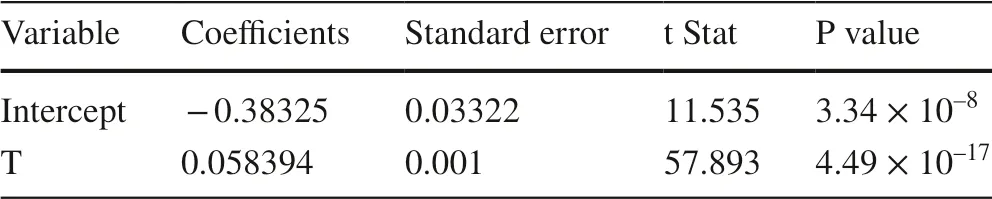

Table 2 Estimation parameters for MLR analysis based on Eq.8

When the saturated water vapor function is determined, the water vapor pressure can then be derived using the following equation (Eq.3):

HRdenotes the relative humidity, 0 ≤ HR≤ 1.If HR=1,then the saturation point has been reached.The function of the individual burned area can then be estimated (Eq.4).The following functional form was assumed:

It was assumed that KP< 0 and KT> 0.The parameters were estimated following MLR analysis (Eq.5).

Estimated individual burned area function B=B (P, T,W)

Individual burned area was also estimated as a function of three independent variables (Eq.6) and (Eq.7).

W is wind speed in km h-1.Regression analysis is W3/1000 to give parameter values on a more convenient scale.This is therefore the same as the previous model but with an additional independent variable, W3/1000.Multiple regression analysis was then carried out.

Results

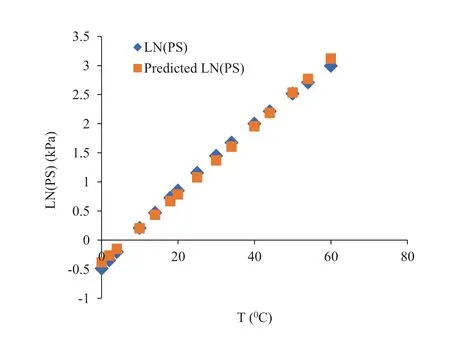

Once the function of the saturated water vapor pressure was determined, MLR analysis of Eq.8 showed a highly significant relationship between PSand T with R2=0.998(Table 2).

The natural logarithm of the saturated water vapor pressure was estimated as a function of the air temperature.An exponential function for the temperature interval 0–60 °C was estimated (Fig.3) and obtained using Eq.8:

Fig.3 Observed and predicted natural logarithms of saturated water vapor pressure (kpa) based on Eq.8 with respect to air temperature(°C).The figure confirms the natural logarithm of saturated water vapor pressure as a function of air temperature, as in Eq.8 .The results show that the model performed well (R2=0.998) with LN (P S) indices and independent variable (T), so the predicted individual burned area closely resembled the observed area

The function can be expressed as:

Results from estimated individual burned area function B=B (P, T)

MLR results calculated with two explanatory variables were analyzed to determine their interaction with the burned area.Regression analysis using Eq.5 gave a highly significant result with the two explanatory variables LN (P) and T(Table 3), where R2=0.760, the F-value of the regression was 180 and the p-value of the regression was 6.94 × 10–36.

Table 3 Estimation parameters for MLR analysis based on Eq.5

The individual burned area was shown to be a function of temperature and water vapor pressure (Eq.10).

This function can be expressed as:

The expression of water vapor pressure is included in the equation:

This can be expressed as:

Finally, the individual burned area was estimated as a function of relative humidity and air temperature, as shown by Eq.14 and in Fig.4.

Fig.4 Individual burned area (m 2 ) as a function of relative humidity (between 0 and 1) and air temperature (°C) based on Eq.14.The figure confirms that if air temperature increases and relative humidity decreases, the air can contain more water and the fuel becomes drier.As a result, the size of the individual burned area is reduced

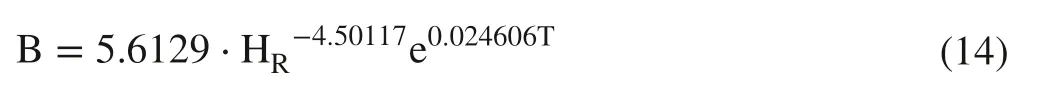

After fitting the parameters to the combined data, residuals were analyzed concerning relative humidity and air temperature variables in Eq.10.The distribution of these residuals did not indicate any heteroscedasticity or exclude relevant nonlinearity in the LN (P) and T dimensions.As detailed in Fig.5, the residuals are the difference between the actual value of the dependent variable and the predicted value, according to the estimated model.

Fig.5 Residuals ofindividual burned area model (Eq.10) with respect to a air temperature (°C) and b the natural logarithm of watervapor pressure (kPa).The distribution of the residuals did not indicate any heteroscedasticity or exclude relevant nonlinearity in the LN (P)and T dimensions, i.e., since the points in the residual plots were randomly dispersed, the models described the relationships correctly

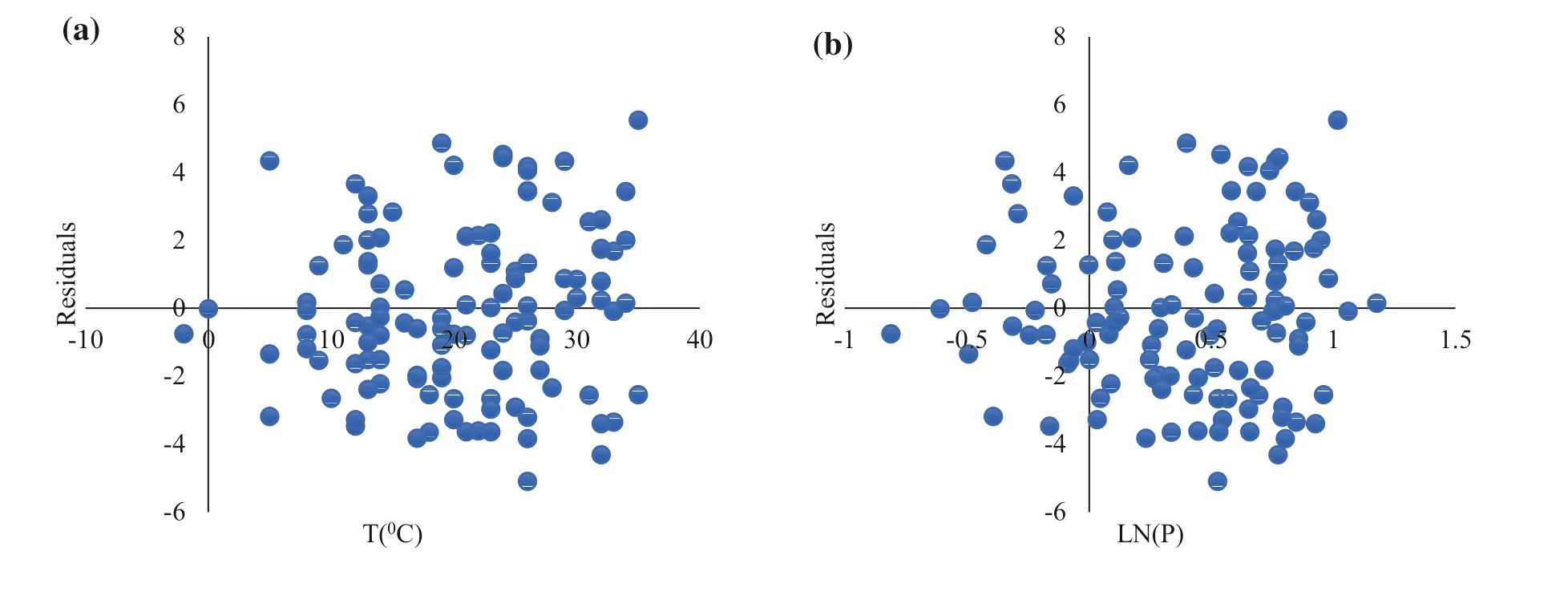

Predicted values of the size of the individual burned area compared to actual values are shown in Fig.6.

Fig.6 a Observed and predicted size ofindividual burned area based on Eq.10 with respect to air temperature (°C) and b the natural logarithm of water vapor pressure (kPa).The results show that the model performed well (R 2=0.760) with LN(B) indices and independent variables, so the predicted burned area closely resembled the observed

Results from estimated individual burned area function B=B (P, T, W)

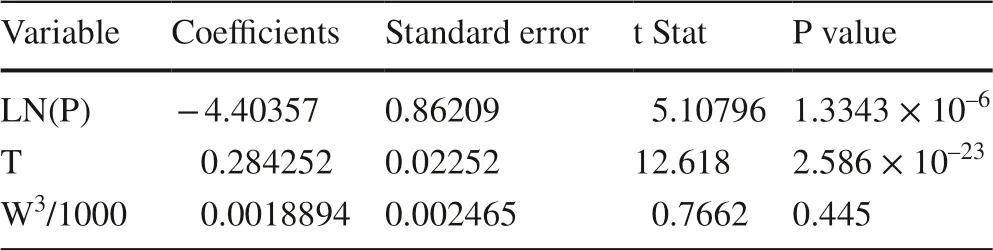

A new MLR, which determined the function of the individual burned area, used the three explanatory variables.Regression analysis of the results of Eq.7 are shown in Table 4, where R2=0.761, the F-value of the regression is 120 and the p-value of the regression is 7.88 × 10–35.

Table 4 Estimation parameters for regression analysis based on Eq.7

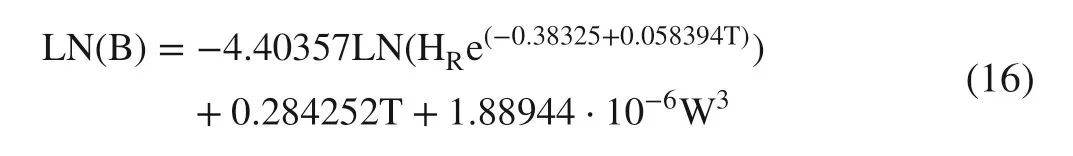

Equation 15 indicates how the individual burned area was estimated as a function of water vapor pressure, air temperature and wind speed cubed, which is proportional to wind energy.

The expression for water vapor pressure is inserted into the equation.

This can be expressed as:

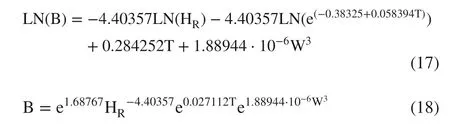

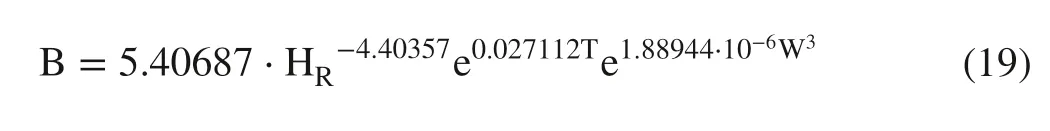

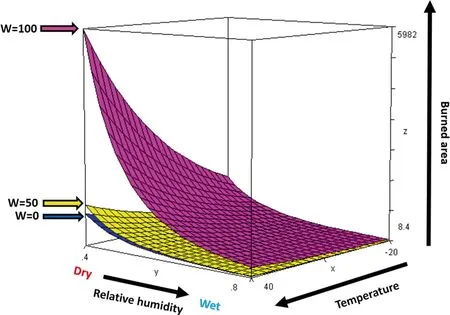

Finally, the individual burned area was predicted as a function of relative humidity, air temperature and wind speed cubed, as shown in Eq.19 and Fig.7.

Wind speed sensitivity analysis

An analysis was carried out to investigate how wildfire size varies with changes in wind speed.For this process, the wind speed was increased from zero to 50 and 100 km h-1.The empirically-estimated function was used for this purpose(Eq.19).The results show that if wind speed is increased,the size of wildfires increases (Fig.7).

Fig.7 Individual burned area (m 2 ) as a function of relative humidity(a value between 0 and 1), air temperature (°C) and wind speed (kmh -1 ) based on Eq.19.The figure shows the simultaneous effects of relative humidity, air temperature and wind speed on forest wildfire size in the Prague-East District of the Czech Republic.Increases in air temperature and wind speed and a reduction in humidity increase the size of the wildfire

Discussion

In this research, the simultaneous influences of climate variables (air temperature, humidity, and wind speed) on individual burned areas were estimated for the Prague-East forests of the Czech Republic.It is especially important for firefighters to be able to predict the size of a wildfire in order to determine manpower and resource allocation (Özbayoğlu and Bozer 2012).The MLR method was used in combination with theoretically derived and motivated nonlinear transformations to determine a relevant multi-dimensional nonlinear forest wildfire function, where the properties were consistent with the presented theoretical foundations.These models were developed to use the fewest predictors to illustrate the greatest variability in the response variable(Graham et al.2003).In earlier studies, MLR techniques have often been used to determine different kinds of linear functions.For example, Oliveira et al.( 2012) presented and compared the application of traditional MLR and Random Forest to identify the main structural factors that explain the likelihood of fire occurrence on a European scale (the European Mediterranean region).The Random Forest model showed higher predictive accuracy than linear regression,reflecting the existence of nonlinear trends.The negative association that appeared in the linear regression model between temperature and fire density might be due to the human causes of fire ignitions in this region, and thus not dependent on temperature.

Yue et al.( 2013) estimated future wildfire activity over the western United States during the mid-twenty-first century.They predicted linear relationships between daily area burned with temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity using regression methods.Their results showed increased air temperatures and drier summer climate leading to larger annual area burned.Kitzberger et al.( 2017) created an MLR of log-transformed annual area burned on all seasonal climate variables using a linear model function.Their results showed that spring and winter temperatures influence directly on annual area burned.Viganó et al.( 2018)used an MLR model to determine mathematical modeling for predicting the number of wildfires using climate variables.They established a simple linear relation between a dependent variable and several independent variables.Their results showed that the model was not strictly linear based on the analysis regression.They concluded that other variables should be inserted to improve the performance of this technique.The present research, compared to previous studies,includes theoretical foundations, derivations, motivations,and consistent estimations of a nonlinear, multi-dimensional wildfire size function.

Two versions of our model were developed so that an alternative would be available if any of the parameters were not applicable.The difference between this model and past studies is its f lexibility in terms of data availability.Different combinations of explanatory variables were considered.There are no formal errors in the estimations of the regression models.The parameter values produced the expected signs.The t-values of the parameter values have been investigated and are entirely satisfactory.

The model was evaluated according to the residuals.The results showed that the first model involving LN (B) indices and independent variables performed well (R2=0.760), with the predicted burned area corresponding closely to the actual burned area.In the second model, wind speed was added to enhance the prediction of the size of the forest wildfire and further improve the utility of prediction methods in the regression equation (R2=0761).

The most accessible data was initially used, such as air temperature and water vapor pressure, so the individual burned area was estimated as a function of both; water vapor pressure is of particular interest in many chemical and technical applications and many kinds of tables and approximations have been produced.Over time, and with access to an available water source, water vapor pressure converges on the saturated water vapor pressure.The results show that increased water vapor pressure in the air reduces the size of a wildfire.If the air temperature increases, it may contain less water and the fuel becomes drier.As a result, the size of the individual burned area increases.It is natural to assume that wildfires grow more slowly if there is more water in the air (higher water vapor pressure); the fuel is wetter and takes longer to become sufficiently dry to start burning, so the individual burned area is smaller.

Since relative humidity is the ratio of vapor pressure to saturation vapor pressure multiplied by 100 (Tichy and Kallina 2013), the individual burned area can be estimated as a function of relative humidity and air temperature.However, it takes time for fuel at ground level to be affected by the humidity in the air (Goldammer and De Ronde 2004), so the relative humidity on the days before a wildfire, as well as on the day the fire occurs, may have a significant impact on its size.All these factors lead to higher predicted size.

In previous studies, researchers have used the relative humidity data on the day of the wildfire, e.g., Slocum et al.( 2010), Pérez-Sánchez et al.( 2019), Wood ( 2021).

In the second version of the burned forest area model, the simultaneous influences of three fundamental factors was studied: air temperature, water pressure and wind speed cubed, which is a factor proportional to wind energy.Our results showed that increased air temperature and wind speed increase the size of a wildfire, while increased water vapor pressure reduces the size.

In general, temperature has a direct impact on wildfire ignition because the fuel is closer to the ignition point when the temperature is higher.Humidity is relatively low on hot summer days when the forest is dry, which increases the wildfire size, as the fuel is unable to absorb enough moisture from the air.The wind supplies oxygen, which further dries the fuel and spreads the wildfire across a wider area.The stronger the wind, the greater the size of the wildfire.A relatively low humidity coupled with strong winds and high temperatures can rapidly increase the size of a wildfire(Zelker 1976).

In this study, the hypothesis was that the wind speed cubed influences the size of a forest wildfire, and the energy of the wind is proportional to the wind speed cubed.In other words, wind power varies with wind speed cubed, so doubling the wind speed gives eight times the wind power (Gipe 2004).Previous studies have evaluated the size of forest wildfires based on wind speed, e.g., Aghajani et al.( 2014),Salis et al.( 2018), Cruz and Alexander ( 2019), and Pérez-Sánchez et al.( 2019).Estimates of the wind speed result in the expected indication, (according to the hypotheses),but a fairly low absolute t-value.This may be because there have been few occasions when wildfire has occurred simultaneously with strong winds in the region under investigation.T-values for the W parameter are likely to be higher for future empirical observations in regions where strong winds are more frequent; these types of result would be expected since they are consistent with those of previous studies.

For this study, the individual burned area was modelled as a function of climate variables alone, as a base for future projections.Several studies have supported our results by asserting that climate variables play an important part in wildfire size prediction and increase the accuracy of predictions.Carvalho et al.( 2010) investigated the relationship between the occurrence of fires across Portugal and the climate of the area burned.The results showed that a rise in air temperature and a reduction in precipitation over the study period greatly affected the size of the wildfire.Amatulli et al.( 2013) modeled the total burned area in the Mediterranean region as a function of climate, and subsequently used the resulting models to assess the expected burned areas in EU countries most affected by forest wildfires.Wu et al.( 2015)estimated future changes in burned area at European and sub-European scales.Their results have shown that wildfire size in Europe is sensitive to climate change.

Conclusions

The methodology was appropriate for studying how the size of a forest wildfire is affected by climate variables.Since air temperature (heat), wind speed and moisture in the air may change as a result of global warming, the size of a forest wildfire as a function of these fundamental factors was estimated.The model shows that changes in factors caused by ongoing climate change may result in significant changes in the size of forest wildfires.The current number of forest wildfires that occur in the Czech Republic is small compared to many other countries.However, the development of the wildfire model as a forest management strategy, in the context of climate change, is a key challenge for future resource management and will play a part in future optimization of fire management studies in the Czech Republic.For further studies involving forest wildfire models, it is recommended that more parameters be included, such as distance to wildfire stations, topography and vegetation.

AcknowledgementsWe thank Prof.Bin Li (Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Forestry Research), Prof.Ruihai Chai (Editor) and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive scientific comments.

Declarations

Conflict ofinterestThe authors declare no conf licts ofinterest.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Journal of Forestry Research

- Reversibly photochromic wood constructed by depositing microencapsulated/polydimethylsiloxane composite coating

- Surveillance of pine wilt disease by high resolution satellite

- Adaptation of pine wood nematode, Bursap helenchus xylophilus,early in its interaction with two P inus species that differ in resistance

- Pine wilt disease detection in high-resolution UAV images using object-oriented classification

- Transcriptome analysis shows nicotinamide seed treatment alters expression of genes involved in defense and epigenetic processes in roots of seedlings of Picea abies