Ground vegetation, forest floor and mineral topsoil in a clear-cutting and reforested Scots pine stands of different ages: a case study

2022-09-08DovilGustienIvetaVarnagirytKabainskienVidasStaknas

Dovilė Gustienė ·Iveta Varnagirytė-Kabašinskienė ·Vidas Stakėnas

Abstract Scots pine ( Pinus sylvestris L.) is a dominant tree species on nutrient-poor sandy soils in the Baltic region’s hemiboreal forests.A final clear-cut in commercial stands is a common practice.However, the maintenance of relatively stable vegetation indices and ecological processes throughout the rotation promote new scientific and social debates.Overall, clear-cuttings disturb forest functions for a certain period, i.e., phytocenoses with forest-based species composition, biodiversity, and vegetation cover.Soil organic carbon (SOC) and nutrients can also be affected.As key indices, ground vegetation, SOC and main nutrients in the forest floor and in 40-cm topsoil layer were analysed in the clear-cuttings (not reforested) and in reforested 10-, 30-, and 101-year-old Scots pine stands in 2020.The results show an increase in species richness at the beginning of stand formation up to 30 years after clear-cutting; species typical of a mature forest occurred relatively quickly post-harvest.The mean mass of forest floor vegetation was negatively related to the richness of ground vegetation species.Forest floor pH consequently decreased with stand age.Higher SOC levels were in the mature stand.In the mineral topsoil layers, total SOC and total nitrogen were in the upper 10-cm layer in the 30-year-old stand.A post-harvest peak in mineral N concentration was observed and other nutrients, especially mobile P2 O 5 , K 2 O, Ca 2+ and Mg 2+ , increased the clear-cuttings and in the 10-year-old stand compared to the mature stand.

Keywords Pinus sylvestris · Species cover·Richness ·Soil organic carbon·Soil nutrients·Mature stand

Introduction

The role of forests in the context of climate change mitigation is widely discussed, highlighting the importance of these ecosystems.Forests store large amounts of carbon (C)in various ecosystem compartments, both in soil and in plant biomass, accumulating carbon dioxide through continuous C sequestration (Nave et al.2010; Kowalska et al.2020).The continuing functioning of forest ecosystems ensures natural absorbing of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (Pregitzer and Euskirchen 2004; Pan et al.2011).The growing demand for timber and biomass for energy under conventional forest management practices does not presuppose consideration of alternatives to clear-cutting harvesting (Puettmann et al.2015).Therefore, final clear-cutting when mature stands are felled during one operation is still widely used.On the other hand, there is a growing debate about the compatibility of such forest harvesting with the maintenance and sustainable use of forest ecosystems (ME 2016, 2020; Maciūnaitė 2017).Also, clear-cutting, which destroys forest structure, is likely to disrupt C sequestration for some time (Nave et al.2010).

Despite the stem-only or whole-tree harvesting, clear-cutting operations alter ground vegetation species composition and cover, soil organic matter (SOC) and nutrient imbalances in the forest floor and in the mineral soil (Gundersen et al.2006; Armolaitis et al.2008, 2018; Nave et al.2010;Česonienė et al.2019).Until plant communities again reach the pre-harvest level, the specific forest structural elements and functions (vegetation response, soil chemistry.)most likely will occur on reforested sites of different ages.It can be argued hypothetically that differences from the mature stand should continue for a limited time.If changes in ground vegetation indices could be detected soon after clear-cutting (Česonienė et al.2019; Stefańska-Krzaczek et al.2019; Ilintsev et al.2020), changes in the soil could be less noticeable.An exception is a post-harvest peak in nitrate concentrations in runoffwater which is caused by more intensive mineralization of organic matter in the clearcuttings (Bergholm et al.2015; Armolaitis et al.2018).Previous studies have shown that the loss of other nutrients due to forest harvesting during the whole stand rotation was compensated by atmospheric precipitation and litterfall in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestrisL.) stands on nutrient-poor sandy soils (Armolaitis et al.2013).

In order to clarify the processes that occur in clear-cuttings of forest stands, both short-term and long-term studies are carried out to monitor nutrient changes and the risk of mobile compounds leaching to groundwater (Gundersen et al.2006; Armolaitis et al.2008, 2018; Laudon et al.2009;Löfgren et al.2009; Palviainen et al.2014; Česonienė et al.2019).In line with the changing climate, the assessment of greenhouse gas emissions and SOC stocks in forests and logging sites has also received particular attention (Schulze and Freibauer 2005; Nave et al.2010; Schelker et al.2012).

It is well-known that soil is an important C and nitrogen(N) pool, including approximately 75% of organic C and 95% of N (Schlesinger 1997).C accumulation in forest ecosystems occurs mainly through vegetation, litter/floor and in the mineral soil (Lee et al.2014; Laf leur et al.2018).Plant communities, their biodiversity and cover, and forest floor alter the C cycle and interactions between soil organic C and N (Schulze et al.2000).However, accurate estimates of soil C and N during a forest rotation are still lacking.

As early successional species, Scots pine has a wide ecological plasticity but is light demanding.The species prevalence depends on edaphic conditions; therefore, most Scots pine stands grow on nutrient-poor soils.Despite the wide distribution of Scots pine, previous studies have not identified associated plant species or communities throughout its geographical and edaphic regions (Kelly and Connolly 2000).This warrants the need for such studies in different regions and habitats.In Lithuania, forest management practices show that clear-cuttings are the major disturbance in Scots pine forests.In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the assessment of the impact of clear-cutting on understory vegetation and soil (Česonienė et al.2019).However, more attention has been paid to the initial, shortterm effects.Therefore, this study aimed to identify the main changes in ground vegetation composition, content of soil organic carbon and other nutrients on the forest floor and in the mineral topsoil layers in clear-cuts and in Scots pine stands of different ages.Our hypothesis was that the most important changes in forest vegetation, forest floor and mineral topsoil are likely to be recorded in recent clear-cuttings up to the initiation stage of the stand, which is represented by sites of about 10-years old, and that the 30-year-old stand would become more similar to a mature forest.

Materials and methods

Study site

The study was carried out in south-eastern Lithuania (54°38′16.19″ N; 24° 56′ 3.59″ E) on land of the Trakai Regional Division of State Forest Enterprise in July–September 2020.Mean annual temperature was 6.9 °C, and mean annual precipitation 695 mm over 1981–2010.During 2020, mean temperatures were about 2 °C above and rainfall 120 mm below normal.

Four different study sites, including a clear-cut (one year after harvesting) and 10-, 30-, and 101-year-old Scots pine(Pinus sylvestris) stands were selected as typical Scots pine stands within this area.For all sites, the forest type wasPinetum vaccinio-myrtillosumand the forest site type was Nb–oligotrophic mineral soil with a normal moisture regime,according to Lithuanian classification (Vaičys et al.2006).The soils are arenosols of coarse sand with low (< 5%)clay + silt content (Buivydaitė et al.2001; IUSS Working Group WRB 2007).The diagnostic ground vegetation species wereVaccinium myrtillusL.andV.vitis-idaeaL., and moss speciesHylocium splendens(Hedw.) Schimp.,Pleurozium schreberi(Brid.) Mitt.andPtilium crista-castrensis(Hedw.).

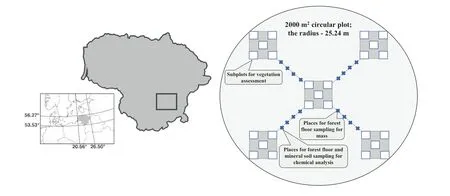

For the assessment of selected vegetation and soil parameters, a 2000 m2circular plot with a radius of 25.24 m was established (Fig.1).

Fig.1 Location of the study in Lithuania and the scheme of ground vegetation assessment, forest floor and mineral topsoil sampling

In clear-cut, harvesting was carried out in 2019.Boles and logging residues except for stumps and roots, were removed from this site.The 10-year-old stand was initially established as a pure Scots pine with total density of 11,150 stems ha-1was specific because it comprised a small number of naturally regenerated birch trees in the undergrowth.These birch seedlings are to be removed during the first thinning up to 15-year-old according to the Lithuanian forest management practices.The 30-year-old stand was 90% Scots pine and 10% Norway spruce (Picea abies(L.) H.Karst).Stand volume was 165 m3ha-1, basal area 28 m2ha-1, and mean DBH 14 cm.The mature 101-year-old stand was 100%Scots pine with small Norway spruce trees in the understory.Stand volume was 415 m3ha-1, basal area 36 m2ha-1, and mean DBH 46 cm.

Vegetation assessment

The understorey vegetation was studied at the four different sites during the period of maximum herbaceous plant cover in July 2020.Assessment was carried out on five 10 m × 10 m plots located in the centre of the site and at 0°, 90°, 180° and 270° azimuths from the centre (Fig.1).In each site, the assessment was carried out in 25 vegetation quadrates (1 m × 1 m subplots).A 100 cm2square mesh frame was used to assess % cover of each species visually.The mean value of each species cover was then calculated per site.Frequency of each species was determined as the number of subplots in which the species was found divided by the total number of subplots (Ehlers et al.2003).

Species assessment was made in three different vertical strata: moss layer, herb layer (all non-ligneous, and ligneous ≤ 0.5 m height), shrub layer (non-ligneous and ligneous) > 0.5 m height, and tree layer > 5 m height according to Canullo et al.( 2011).

For species diversity at the different sites, ground vegetation species richness (number of species) and Shannon diversity index (H′) were evaluated (Magurran 2004).The Shannon diversity index (H′) was calculated by Eq.1:

wheren iis the cover of theith species;Nis the total cover of vegetation on the site.

Soil sampling and chemical analysis

Forest floor mass [forest litter (OL) + fragmented litter(OF) + humified litter (OH)] was determined by sampling within a 25 cm × 25 cm metallic frame.For mass determination, composite floor samples were obtained from four subsamples, oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant mass, and weighted.

Mineral topsoil samples of the 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, and 20–40 cm layers were collected using a metallic soil auger in August–September 2020.Four composite samples were combined from 10 subsamples collected systematically in each plot with the distance between sampling points of at least 5 m.

Indicators determined in the forest floor and mineral topsoil samples were: pH determined in a 0.01 M CaCl2suspension (ISO 10390:2005), organic carbon (C) determined with a Heraeus apparatus (ISO 10694, dry combustion at 900 °C),and total nitrogen (N) analysed using the Kjeldahl method(ISO 11261).Concentrations of mineral N were determined by the spectrometric method (ISO 14256-2) in 1 M KCl extraction: NH4-N using sodium phenolate and sodium hypochlorite, and NO3-N using sulphanilamide.Mineral N (Nmin) was determined by summing NH4-N and NO3-N.Mobile potassium (K2O) and phosphorus (P2O5) were determined by the Égnér-Riehm-Domingo (A-L) method (Égnér et al.1960).Soil chemical analyses were conducted in the Agrochemical Research Laboratory of LAMMC.

Statistical analysis

To find the significant differences between the sites,ANOVA followed by a post-hoc LSD test was used.Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE).Different letters next to the mean values are statistically significantly different atp< 0.05 between the sites.Pearson correlation measured the linear correlation between two variables.Statistical analyses were conducted using STATISTICA 12.0(StatSoft.Inc, 2007) software.

Results

Ground vegetation in the clear-cutting and reforested Scots pine stands

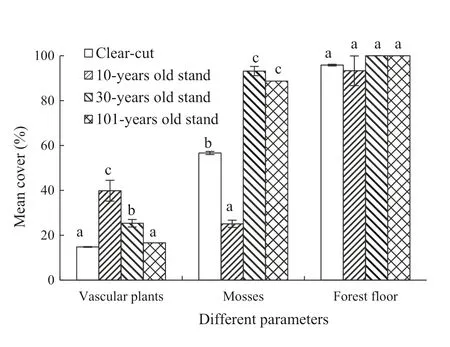

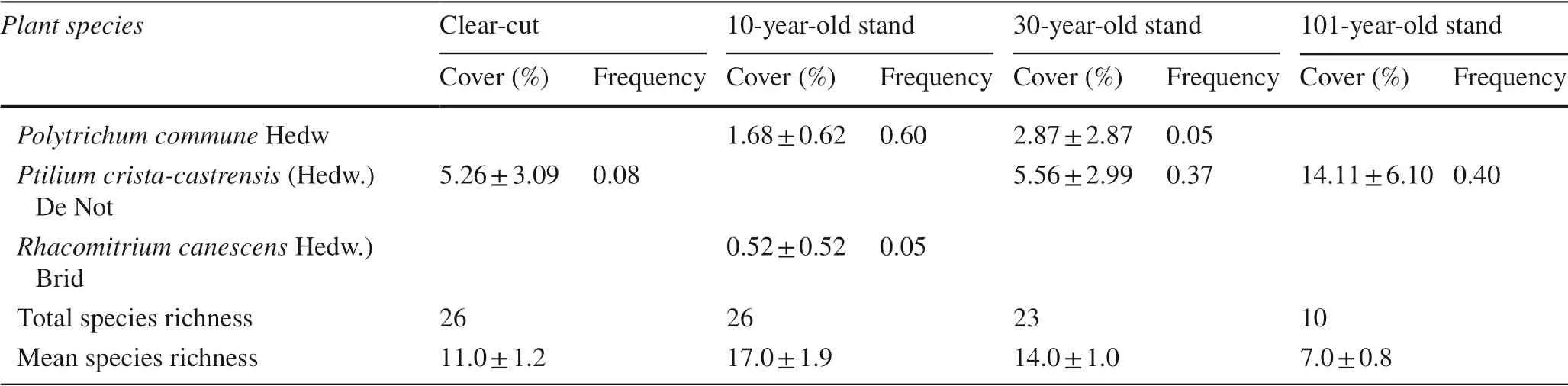

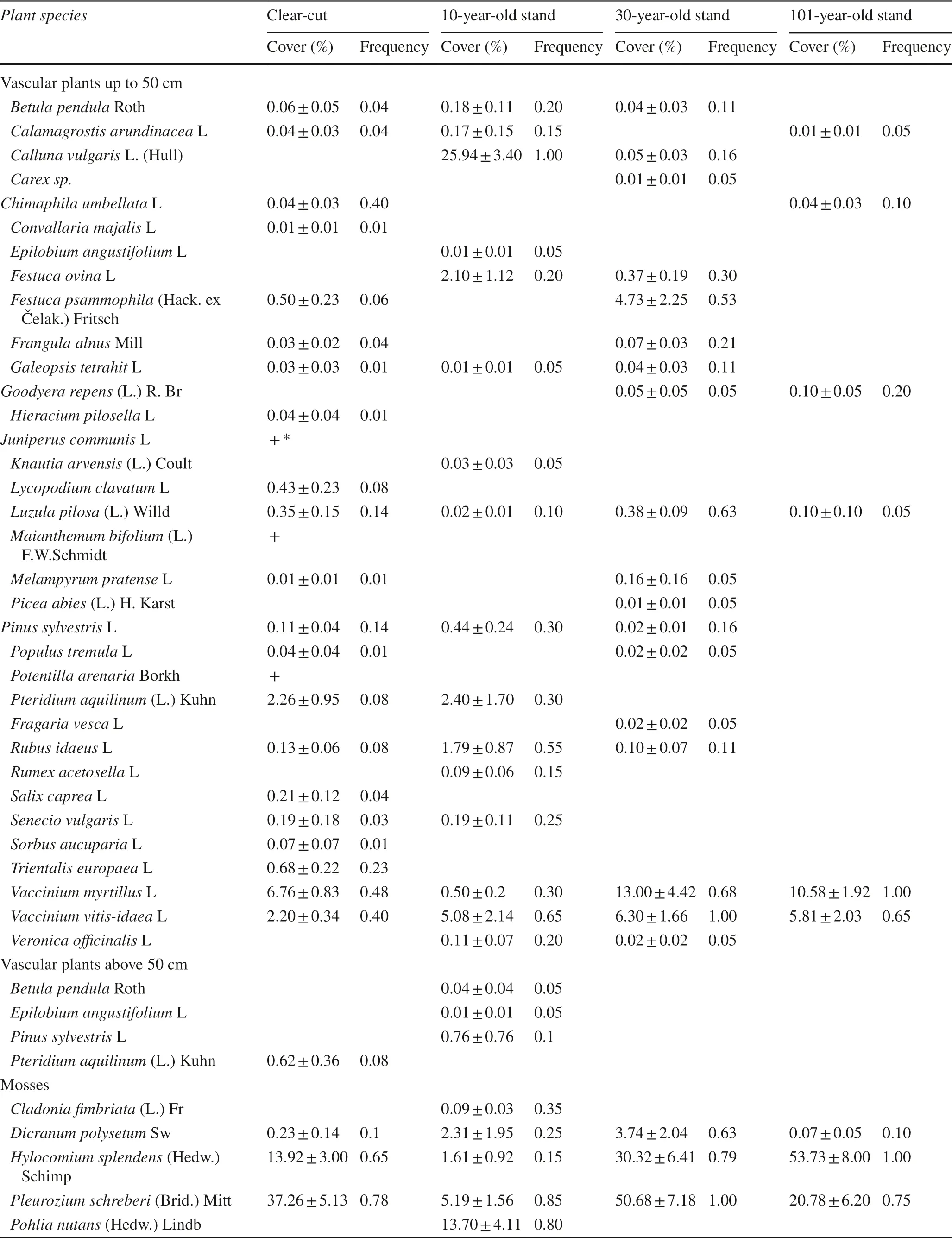

Moss cover was the most numerous at all sites with some differences in species composition due the specific stand age(Table 1).In the clear-cut,Pleurozium schreberi(Brid.) Mitt.dominated, followed byHylocomium splendens(Hedw.)Schimp.andPtilium crista-castrensis(Hedw.) De Not.In the 10-year-old stand,Pohlia nutans(Hedw.) Lindb., Pleurozium schreberiandDicranum polysetumSw.covered 14.0%,5.0%, and 2.0%, respectively.In the 30-year-old stand,Pleurozium schreberiandHylocomium splendenswas the largest cover withPtilium crista-castrensisandDicranum polysetumat 3.7 to 5.6%.Three main species of mosses were found in the mature forest: 14.1% forPtilium crista-castrensis,20.8% forPleurozium schreberiand 53.7% forHylocium splendens.Compared with the other sites, the largest moss cover was in the mature stand.However, the largest number of moss species was in the 10-year-old stand; the number of moss species decreased with stand age.However, the lowest mean moss cover was in the 10-year-old stand (Fig.2).

The largest total number of species of vascular plants >50 cm in height was in the clear-cut and 10-year-old stand(26 species) (Table 1).The number of vascular species in the 30-year-old stand was 23 species.Ten species of vascular plants, typical for the forest typePinetum vacciniomyrtillosum, were found in the mature stand.In the clear-cut,Vaccinium myrtilluscover was almost 7%, and the cover ofVaccinium vitis-idaeaandPteridium aquilinumexceeded 2%.In both 30- and 101-year-old sites,Vaccinium myrtillusandV.vitis-idaeawere 11–13% and 6%, respectively.There were no statistically significant differences between the clear-cut and the mature forest.

The highest mean species richness was in the 10- and 30-year-old sites at 17 and 14 species, respectively (Table 1).However, the lowest average species richness (7) was in the mature forest.The forest floor cover did not show significant differences between the sites (Fig.2).However, there was still a strong negative correlation between species richness and forest floor mass withR= - 0.854 (p< 0.05).

Fig.2 Mean cover (%) of vascular plants, mosses, and forest floor at different sites; bars are mean ± SE ( n = 4); different letters a, b and c indicate statistically significant differences between sites ( p < 0.05)

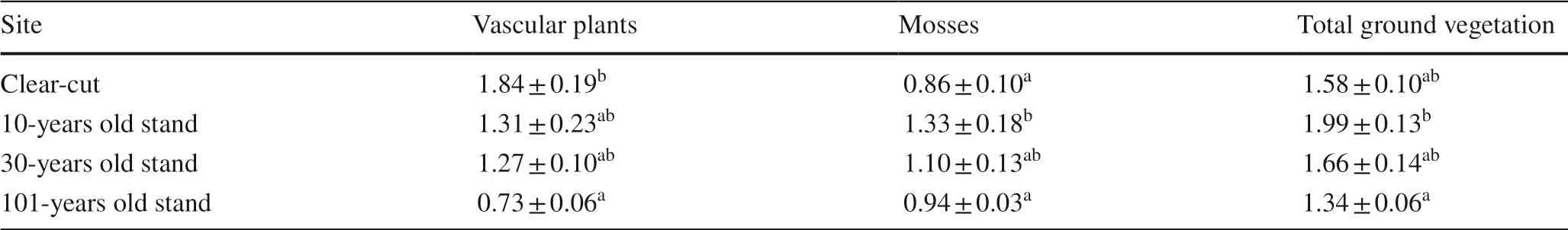

The highest Shannon species diversity indexH′was for ground vegetation and mosses in the 10-year-old stand compared the clear-cutting and the sites (Table 2).The highest Shannon index for vascular plants was at the clear-cut site.The lowest Shannon index for all vegetation (ground vegetation, vascular plants, and mosses) was in the mature stand,indicating the lowest ground vegetation diversity at this site.

Soil carbon and nutrients in the forest floor and mineral topsoil

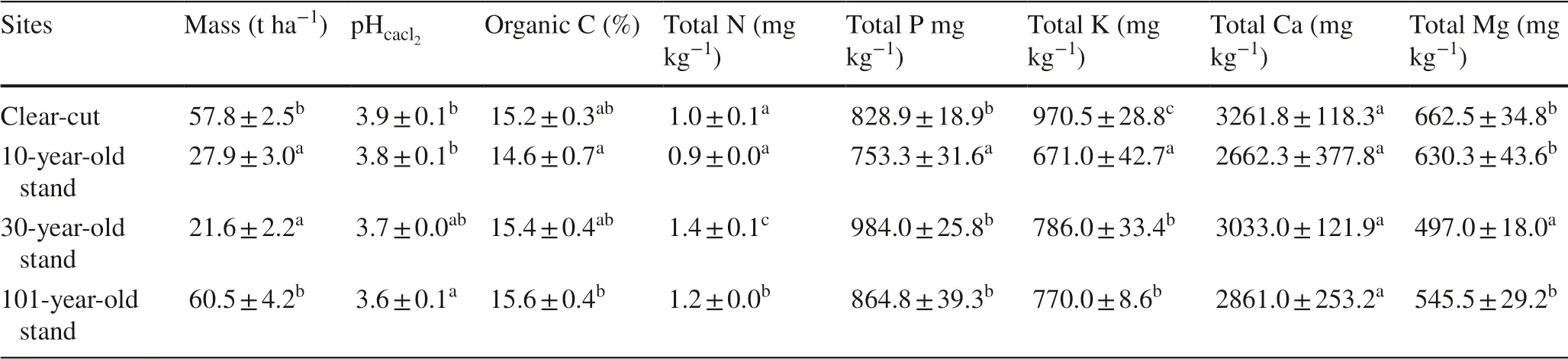

The highest average forest floor mass (OL + OF + OH) was for the 101-year-old stand.Forest floor mass in the clear-cut site was similar to that of the mature stand (Table 3).Such results could be because of a shorter time after harvesting and changes in forest floor could only occur later.

The mean mass of the forest floor was 2.2–2.9 times lower 10–30 years after harvesting than in the mature stand(Table 3).Higher pH values were in the clear-cuttings and decreased with increasing stand age.The highest concentration of organic carbon was in the 101-year-old stand, while the highest total N was in the 30-year-old stand.The lowest C concentration was in the 10-years old stand.A significantly lower total P was found in the 10-years old stand (the difference from the clear-cut site was 1.4 times) and of total Mg in the 30-years old stand (the difference from the clearcut site was 1.3 times).

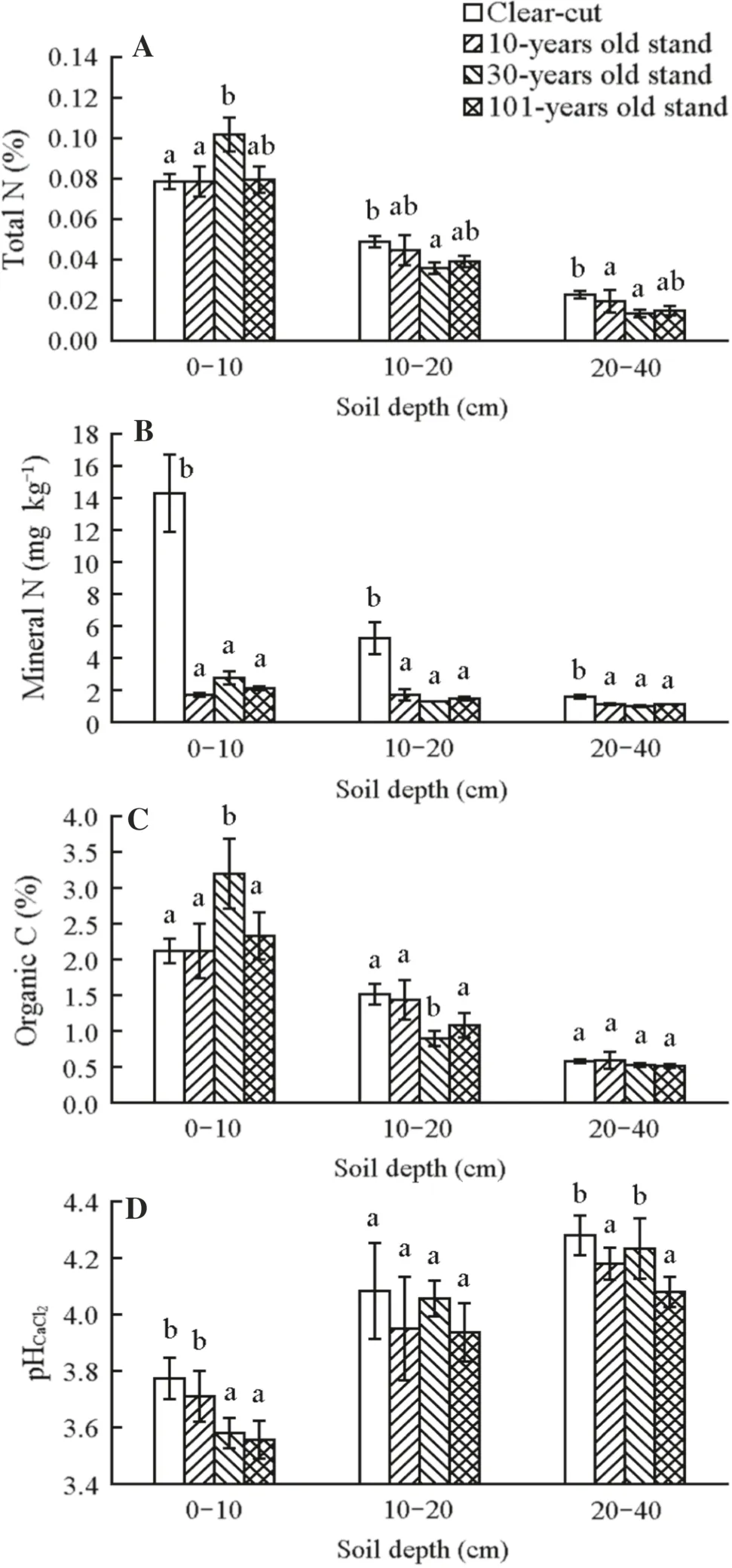

Total N was 1.3 times higher in the upper 10-cm mineral topsoil layer of the 30-years old stand than in the mature forest (Fig.3 A).However, in the 10–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers, a 1.3 times higher concentration of N was found in the clear-cutting site than in the 30-year-old stand.The data show a significant increase of mineral N in the fresh clear-cutting, the highest amounts were in the 0–10 cm and 10 - 20 cm layers (Fig.3 B).The values differed from the mature stand by 7.0, 3.6, and 1.4 times for the 0–10 cm,10–20 cm and 20–40 cm layers, respectively.The highest concentration of organic C was in the 10-cm layer of the 30-year-old Scots pine site (Fig.3 C).This value was 1.4 times higher than organic C levels in the mature forest.However, in the 10–20 cm topsoil layer of the 30-year-old stand, SOC concentration was 1.2 times lower than in the mature forest.The pHcacl2values in the mineral 0–10 cm topsoil showed the most significant variation between sites(Fig.3 D).The highest pH values ( pHcacl23.7–3.8) were in the fresh clear-cut and 10-year-old Scots pine site.The lowest pH ( pHcacl23.6) was in the 30-year-old site and the mature 101-year-old forest.However, no significant differences between the sites were found in deeper topsoil layers.

Fig.3 A Mean concentrations of total nitrogen (N, %), B, mineral N(mg kg -1 ), C, organic C (%), D, and pHcacl2 on different sites (clearcut, and 10-, 30- and 101-year-old Scots pine stands).Bars show the mean ± SE ( n = 4); different letters a and b indicate statistically significant differences between sites ( p < 0.05)

Table 4 shows an overview of the mean concentrations of other soil nutrients at the different sites.Due to the effect of clear-cutting, the concentrations of mobile elements (P2O5,K2O, Ca2+and Mg2+) changed more than the concentrations of total elements (P, K, Ca and Mg).Clear-cutting tended to increase the concentrations of total Ca and Mg; also, P2O5,K2O and mobile Ca2+.

Table 1 (continued)

Table 1 Cover (%) and frequency of plant species at different sites

Table 2 Shannon species diversity index ( H′) of vascular plants, mosses and ground vegetation at different sites; different letters a and b indicate significant differences among sites within the same plant group ( p < 0.05)

Table 3 Mean mass of forest floor (t ha -1 ), pHcacl2 , and mean concentrations of organic C, total N, P, K, Ca and Mg at different sites; different letters a, b and c indicate significant differences among sites ( p < 0.05)

Table 4 Mean (± SE) concentrations of total P, K, Ca and Mg, P 2O 5, K 2O , mobile Ca2 + and Mg2 + in mineral topsoil layers at different sites(clear-cut, and 10-, 30- and 101-year-old Scots pine stands); different letters a, b and c indicate statistically significant differences between sites ( p < 0.05)

Discussion

The present study identified the changes in ground vegetation and forest soils in a clear-cut and reforested sites of Scots pine of different ages.Recent forest management practices in Lithuania are moving towards sustainable forestry,requiring the maintenance of all ecological processes and biodiversity throughout the whole stand rotation.

This study found that the largest number of ground vegetation species, including both vascular plants and mosses,was found in the clear-cut and the 10-year-old stand, and deceased with stand age.Some species, typical of mature stands (forest-dependent species), were already present in the 30-year-old stand:Goodyera repens,Luzula pilosa,Vaccinium myrtillus,Vaccinium vitis-idaea,and the mossesDicranum polysetum,Hylocium splendens,Pleurozium schreberiandPtilium crista-castrensis.

The diagnostic species found in our survey corresponded well with those obtained by Stefańska-Krzaczek et al.2019 in Scots pine stands of similar ages.The most abundant understory vascular plant species in the study area wereV.myrtillus,V.vitis-idaea, andCalluna vulgaris(Karazija 2003; Hekkala et al.2014; Stefańska-Krzaczek et al.2019).This suggests that reforested sites could recover during the first 30-year period.Previous studies found that different types of silvicultural management highly modify ground vegetation, even under the same tree species (Tyle 1989;Ilintsev et al.2020; Marozas and Sasnauskienė 2021).For example, shelter wood cuttings in Scots pine stands resulted in an increase of herbaceous species but decreased the abundance of mosses and lichens (Marozas and Sasnauskienė 2021 ).Among other practices, clear-cutting has a drastic impact on vegetation cover, thereby nutrient consumption by vegetation becomes significantly reduced (Finér et al.2003;Palviainen et al.2005; Gundersen et al.2006).Clear-cutting is often shown to have a significant impact on ground vegetation and a decrease in species diversity (Meier et al.1995;Qian et al.1997).However, Battles et al.( 2001) found only a short-term decrease or even an increase in species richness,or no effect due to forest management.

In our study, the 1.6 times higher cover of mosses was in the mature stand than in the clear-cut.This corresponds well with the study by Česonienė et al.( 2019), which identified mosses as the most sensitive to disturbances.Different researchers have noted that a severe ecosystem disturbance could cause stressful conditions that become favourable for some species or that it could be related to greater disruption of the forest floor (Battles et al.2001; Augusto et al.2003).The findings of our study showed that species richness negatively correlated to forest floor mass, reflecting those of Augusto et al.( 2003) who showed that herb cover and species richness were negatively correlated to litter thickness.In addition, the response of species to forest management depends on the characteristics of the species and the ability to adapt to changed environmental conditions (Riegel et al.1995).Nevertheless, the composition of ground vegetation in Scots pine stands depends on stand age, which provides different environmental conditions (Karazija 2003;Stefańska-Krzaczek et al.2019).Previous studies have concluded that age-class forestry based on clear cuttings did not favour epiphytes and epixylous species.Final harvesting was beneficial to light-demanding species and the benefits gradually vanished after canopy closure (Stefańska-Krzaczek et al.2019).It was also noticed that species richness increased after clear-cutting.Changes in microenvironmental conditions create new ecological niches that lead to changes in plant cover and composition and the emergence of different ecological cenotic groups (Ilintsev et al.2020).

In this study, the highest concentration of mineral N was found in the 0–20 cm topsoil on the clear-cut site.Clear-cutting also increased concentrations of P2O5, K2O, P2O5, Ca2+and Mg2+compared with the mature stand, and these differences remained for a relatively long period, 10–30 years after harvesting.As noted by Palviainen et al.( 2004), the fastest decomposition of organic matter and nutrient release in the soil of clear-cuttings is expected during the first three years after harvesting.The level of nitrates stabilizes after four or five years, but the leaching of organic C and other nutrients could be up to 10–20 years after clear-cutting(Palviainen et al.2004, 2014; Gundersen et al.2006; Nave et al.2010).The latter effect in our study could have been occurring between 10 and 30 years of stand formation.For comparison, shelterwood harvesting had a short-term and relatively weak negative effect on soil nutrients, especially mineral N, compared to the effect of clear-cuttings (Marozas et al.2018).

The concentrations SOC and total N in mineral topsoil up to 40 cm depth were analysed at each site: increased concentrations in the upper 10-cm layer were on the 30-year-old site compared to the clear-cut.Typically, during the clear-cutting of a mature stand when all logging residues are removed compared with stem only harvesting, the stocks and concentrations of SOC and nutrients are reduced (Thiffault et al.2011; Achat et al.2015a).The previous studies indicated that nutrient release is often accelerated after clear-cutting where logging residues were removed (Piirainen et al.2009;Finér et al.2016).Such operations can cause nutrient imbalances or C and N depletion in the site.However, these studies had controversial results when assessing the effects of clear-cutting on soil chemistry.For example, Nave et al.( 2010) found little change in mineral SOC after clear-cutting, but James and Harrison ( 2016) reported a significant reduction in SOC of mineral forest soil.The impact of harvesting on SOC and N depends on soil layers and element concentrations or stocks (Vanguelova et al.2010; Achat et al.2015b; Moreno-Fernandez et al.2015).Our results show that C:N ratios were in a range between 25:1 and 39:1 in the 40-cm topsoil layer in all studied sites.The lowest mean C:N ratio was in the clear-cutting site.In the 20-40 cm topsoil layer, the C:N ratio was 39:1 in the 30-year-old site,and 34:1 in the mature stand.Overall, the C:N ratio was the lowest in the fresh clear-cut, then increased to 30:1 and did not change with stand age.Olsson et al.( 1996) showed that whole-tree harvesting increased C:N ratios in the 5-cm soil layer and this effect was detected 16 years after felling.Hume et al.( 2018) also stated that harvesting increased soil C and C:N ratios but reduced soil N.The findings of our study showed higher pH on the forest floor and upper 10-cm mineral topsoil with large variations in the deeper layers in the clear-cutting and 10-year-old sites.However, no statistically significant differences were found between pH values in the 30-year-old site and mature forest.Changes in pH occurred after whole-tree harvesting but had disappeared 26–28 years after harvest as shown by Zetterberg and Olsson ( 2011).However, the differences in nutrient pools due to harvesting were still significant in the upper 20-cm layer.

In general, clear-cutting can affect numerous components of forest ecosystems, including development of phytocenosis, often seen as one of the most sensitive components to environmental changes.Forest harvesting leads to nutrient loss due to increased forest floor mineralization and intensified leaching processes.A reduced ability by vegetation to absorb nutrients also contributes to this process.Otherwise,these effects are not universal for all habitats and climatic zones even for the same Scots pine species.Furthermore,post-harvest nutrient losses and leaching are generally low compared to those removed by stem harvesting (Armolaitis et al.2013).Intensified leaching of nutrients after clear-cutting appears to be relatively small to affect nutrient balance over the long-term (Titus et al.1998).Our study had several limitations and further research is needed to more accurately evaluate soil vegetation and soil chemistry at different stages of stand rotation in hemiboreal forests in the Baltic region.

Conclusions

This study was designed to determine the effect of clearcutting on ground vegetation indices–species richness and cover–and also on forest floor and mineral 40-cm topsoil layer in comparison to 10-, 30-year-old Scots pine stands and a mature 101-year-old stand.The maintenance of ecological processes and biodiversity throughout the rotation is a key aspect in sustainable forestry.The ground vegetation assessment showed an increase in species richness at the beginning of stand formation soon after clear-cutting and a relatively rapid emergence to pre-harvest conditions about 30 years after harvesting.The mean mass of forest floor was negatively related to the richness of the ground vegetation.The highest forest floor pH was in the clear-cutting and consequently decreased with stand age; the highest concentration of organic C was in the mature stand with no clear trend for other nutrients.In mineral topsoil layers,higher modifications were for mineral N and mobile elements in the post-harvest period.The highest concentrations of total C and N were in the mineral 10–20 cm topsoil layer of the clear-cutting, and in the upper 10-cm soil layer of the 30-year-old stands.

AcknowledgementsThis paper is based on Dovilė Gustienė Ph.D.project “Peculiarities of reforestation in clear cuttings of Scots pine stands on nutrient poor sites” (2017–2023), and partly presents research findings obtained through the Long-term Research Program “Sustainable Forestry and Global Changes” implemented by the Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry.This work was conducted within the framework of the CAR-ES network for 2016–2020, funded by Nordic Forest Research.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Journal of Forestry Research

- Reversibly photochromic wood constructed by depositing microencapsulated/polydimethylsiloxane composite coating

- Surveillance of pine wilt disease by high resolution satellite

- Adaptation of pine wood nematode, Bursap helenchus xylophilus,early in its interaction with two P inus species that differ in resistance

- Pine wilt disease detection in high-resolution UAV images using object-oriented classification

- Transcriptome analysis shows nicotinamide seed treatment alters expression of genes involved in defense and epigenetic processes in roots of seedlings of Picea abies