The coupled effect oflight and temperature on dormancy release and germination of Pinus koraiensis seeds

2022-09-08MinZhangJiaojunZhu

Min Zhang ·Jiaojun Zhu

Abstract Elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of environmental factors on seed dormancy and germination will provide guidance for tree regeneration.Toward understanding the coupled effect oflight and temperature on dormancy release and germination of Pinus koraiensis seeds, we set up three light conditions (L200: 200 μmol m -2 s -1 , L20:20 μmol m -2 s -1 , L0: 0 μ m -2 s -1 ) and four storage temperatures [T-5: - 5 °C (50 days), T5: - 5 °C (50 days) + 5 °C(50 days), T25: - 5 °C(50 days) + 5 °C (50 days) + 25 °C(50 days), T15: - 5 °C (50 days) + 5 °C (50 days) + 25 °C(50 days) + 15 °C (50 days)] using imbibed seeds, then quantified phytohormones gibberellic acid (GA 3 ) and abscisic acid (ABA) during the stratification.Germination percentage ( GP ), mean germination time ( TM ), and germination value ( GV ) under 25/15 °C temperature and the three light conditions were then determined.Phytohormone levels and germination performances were significantly affected by light and temperature.No consistent trend was found between the phytohormone levels and GP caused by light levels.Under the three light conditions, ABA concentrations in the embryo and endosperm decreased as storage temperature shifted from T-5 to T25 and increased from T25 to T15;GA 3 decreased in nearly all four storage temperatures.GP reached 40–60% in T25 storage without light irradiance.In the three light conditions, GP and GV were higher at T5 and T25 than at T-5 and T15; so T5 and T25 are considered as optimum storage temperatures for dormancy release and germination.At optimum temperatures, light (L200, L20) significantly increased the GP and GV compared with the dark(L0).At L200 and L20, significant negative correlations between GV and the ABA concentrations and positive correlations between GV and GA/ABA in the seed embryo were found.Temperature played a more important role in primary dormancy release and germination; light was unnecessary for primary dormancy release.Light facilitated seed germination at optimum temperatures.The dormancy release and germination of P.koraiensis seeds were controlled by a decrease in ABA concentrations or an increase in GA/ABA induced by temperature variations.

Keywords Seed germination·Gibberellic acid·Abscisic acid·Germination percentage·Cold stratification ·Primary dormancy

Introduction

Seed dormancy and germination are distinct physiological processes in life cycle of plants (Bian et al.2018).For many plant species, seeds are dormant at maturity and do not germinate until dormancy is released after exposure to optimal conditions (Chen et al.2009; Baskin and Baskin 2014 ).Seed dormancy is a crucial, adaptive feature (Shu et al.2016) to ensure higher survival of emergent seedlings under optimal conditions.Germination is a complex process that can be affected by biotic factors and abiotic factors.Some researchers have proposed that dormancy should be defined as a characteristic of the seed that determines the conditions required for germination rather than the absence of germination (Vleeshouwers et al.1995; Thompson 2000;Fenner and Thompson 2005).When dormancy is considered in this way, any environmental cues that alter the conditions required for germination can be recognized as dormancy release factors (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006).Gibberellic acid (GA) and abscisic acid (ABA) are two prominent phytohormones that regulate dormancy release and seed germination processes (Vishal and Kumar 2018;Barreto et al.2020; Song et al.2020a; Yan and Chen 2020).ABA can induce or maintain seed dormancy, whereas GA stimulates seed germination (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006 ; Baskin and Baskin 2014).Storage at optimal environmental conditions for a specific period can be useful for releasing dormancy and promoting seed germination(Chen et al.2009; Bian et al.2018; Reum et al.2018; Pipinis et al.2020).For example, light irradiance is indispensable to activate the germination of some light-sensitive tree seeds such asBetula papyrifera(Brunvatne 1998),Pinus pinaster(Ruano et al.2009), andHandroanthus impetiginosus(Carón et al.2020).Taxus maireiseeds require wet stratification at alternating temperatures (warm stratification and then cold stratification) to break dormancy.The transition from dormancy to germination induced by suitable environmental factors results from variations in endogenous phytohormones in seeds (Liu et al.2015).Most research has focused solely on one of the two processes, either seed dormancy or seed germination.In the present study, we focused on the two processes from dormancy to germination and clarified the respective roles of environmental cues (light, temperature) in these two processes.

Pinus koraiensisSiebold and Zucc.is a valuable, ancient tree species (Ma1997).It is one of the most important fiveleaved pine species in the northern hemisphere and distributed throughout Northeast Asia’s mixed broadleaved Korean pine forests (MBKPF) (Hutchins et al.1996), the regional climax vegetation type in mountainous areas of eastern China composed ofP.koraiensisand broadleaved tree species.Due to a long history of overuse of forest resources,the MBKPF has undergone severe destruction.Emergent seedlings and saplings ofP.koraiensisare rarely observed in the understory forest even during artificial regeneration.As an important dominant tree species in MBKPF, the unsuccessful regeneration ofP.koraiensisgreatly limits the recovery of MBKPF in broadleaved secondary forests.The deep dormancy ofP.koraiensisseeds is one of the important factors contributing to the failure of natural regeneration forP.koraiensispopulation (Song and Zhu 2016; Song et al.2018).Many ofits seeds do not germinate until the third year after seed maturation due to the existence of primary and secondary dormancy (Song et al.2018).To release the primary dormancy, cold stratification is usually applied toP.koraiensisseeds by mixing seeds into wet sand and burying the mixture the soil to overwinter from November toApril in temperate zones such as Northeast China.In secondary forests, we found that the emergence ofP.koraiensisseedlings varied greatly in microhabitats with different light and temperature conditions.Thus, determining the optimal light and temperature conditions to release seed dormancy and germination should facilitate the natural regeneration ofP.koraiensis.Song et al.(2016, 2018, 2020b) studied seed dormancy ofP.koraiensisunder different stratification temperatures and revealed that temperature significantly affected the dormancy release ofP.koraiensisseeds.Zhang et al.( 2015) indicated thatP.koraiensisseed germination differed significantly under various light transmittances.However,whether the light condition also contributes to dormancy release ofP.koraiensisseeds and whether light and temperature interact to release dormancy and promote germination ofP.koraiensisseeds has not been determined.Answering these questions will inform methods to enhance regeneration ofP.koraiensis.Therefore, here we sought to uncover any coupling of temperature and light conditions on processes from dormancy to seed germination ofP.koraiensisseeds.We also compared germination attributes and GA and ABA dynamics in imbibedP.koraiensisseeds under different light and temperature conditions.Tests were designed to answer the following: (1) How do light and temperature conditions affect GA and ABA levels in imbibed seeds? (2) How does germination of the imbibed seeds respond to the light and temperature conditions? The results will provide a scientific basis for improving natural regeneration ofP.koraiensispopulations and further facilitate the recovery of MBKPFs in broadleaved secondary forests.

Materials and methods

Seed source

In late September 2018,P.koraiensisseeds were collected from at least 10 trees (> 50 years old) in the Qingyuan Forest CERN (Chinese Ecosystem Research Net) to guarantee genetic heterogeneity.Fresh seeds were dried at room temperature in the dark for about 60 days, and then stored at- 20 °C before use.

Experimental design

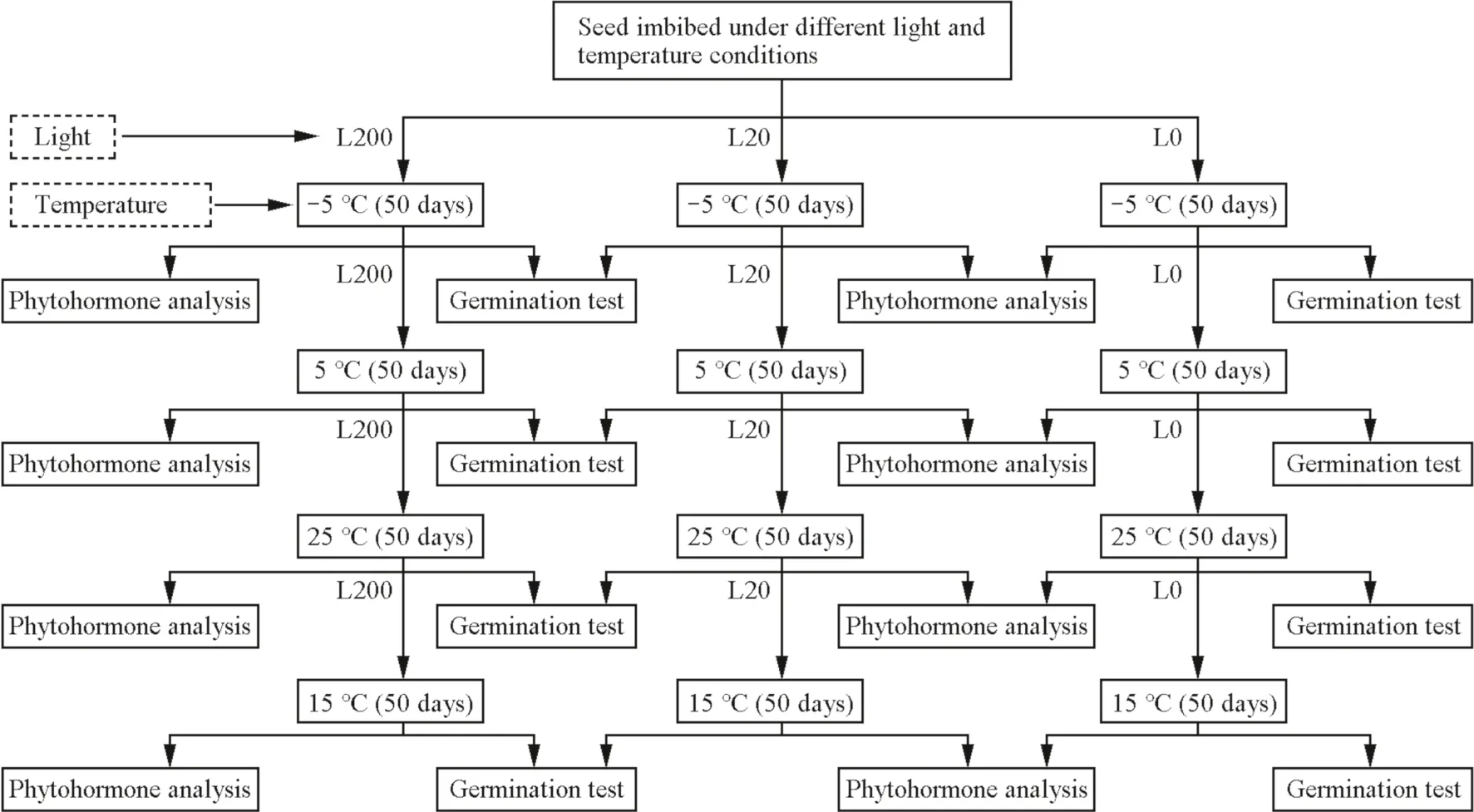

Approximately 10,200P.koraiensisseeds were soaked in distilled water for 7 days for imbibition (the water was changed after 3 days).Floating seeds were removed to ensure viability of the seeds.The imbibed seeds were put on wet sand in a transparent plastic box, and then covered with wet sand to a 1 cm depth.All seeds were stored the same way (30 boxes total) and placed in growth chambers with 200, 20 or 0 μmol m-2s-1(L200, L20, L0) oflight(Fig.1).For each light level, the temperature was set successively at - 5 °C, 5 °C, 25 °C, and 15 °C, with each temperature lasting for 50 days.Two boxes of seeds (ca.800 seeds) from each light level were taken from the growth chamber every 50 days to test germination and quantify phytohormones.Rotten or moldy seeds were counted and removed.The storage temperature treatments forP.koraiensisseeds were designated as T-5 (- 5 °C for 50 days), T5(- 5 °C for 50 days + 5 °C for 50 days), T25 (- 5 °C for 50 days + 5 °C for 50 days + 25 °C for 50 days), T15 (- 5 °C for 50 days + 5 °C for 50 days + 25 °C for 50 days + 15 °C for 50 days).The period of seed stratification was designed to test the effect of environmental factors on the dormancy depth ofP.koraiensisseeds.

Fig.1 Outline of experimental design to test the effect oflight and temperature combinations on germination and phytohormone levels of Pinus koraiensis.L200 is 200 μmol m- 2 s- 1 , L20 is 20 μmol m- 2 s- 1 , L0 is 0 μmol m- 2 s- 1 .In all, 10, 200 seeds were used: 80–100 seeds with three repeats for phytohormone analysis and 50 seeds with five repeats for seed germination test at each temperature change(every 50 days).(The other 80–100 seeds with three repeats were collected at each temperature for later proteome analysis as part of a different study)

After each stratification temperature treatment, 50 seeds with 5 replicates were cultivated at 25 °C/15 °C temperature (represented as T-5 → 25/15, T5 → 25/15, T25 → 25/15,T15 → 25/15 respectively) at three light levels (L200, L20,L0) to test germination and thus the effect oflight and temperature on germination.Germination was defined as the first needle sprout becoming visible (Argyris et al.2008;Zhu et al.2008).Every 80–100 seeds with three replicates were divided into testa, embryo and endosperm which were then ground separately in liquid nitrogen.The embryo and endosperm samples were wrapped in aluminimum foil and stored at - 20 °C before GA3and ABA content analysis.The remaining seeds were used for analyzing the proteome in a study to be reported later.

GA3and ABA in embryo and endosperm ofP.koraiensisseeds were extracted by following the previous methods with some slight modifications (Kojima et al.2009).The seed samples were ground into powder in liquid nitrogen.After that, 500 mg fresh mass was determined for each sample and transferred to a 15 mL falcon tube.After the addition of 4 mL prechilled (- 30 °C) extraction solvent (methanol:water:formic acid=15:4:1), the samples were vortexed for 45 min.Kept the tubes overnight at - 30 °C to extract the hormones (GA3and ABA).After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatant was collected, and the residue was ultrasonically reextracted and centrifugated by following the above method.The extraction supernatants from both steps were combined.Samples and solutions were kept at 4 °C throughout the extractions.HLB and MCX columns were preactivated with 2 mL of methanol and 1 M formic acid.Every 2 mL of the supernatants loaded onto an HLB column and successively washed with 1 mL extraction solvent.The eluates and washing solution were collected together and evaporated to 1 mL solution at 40 °C.The solution was passed through a MCX column eluting with 1 mL methanol and 1 mL of 1 M formic acid.And the methanol fraction was concentrated and redissolved in 0.2 mL of methanol.Then the dissolved solutions were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and transferred to 2 mL LC–MS bottles for UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

Germination indices

The seed germination process was using germination percentage (GP), mean germination time (TM) and germination value(GV) calculated as follows:

where,nis the number of germinated seeds andNtis the total number of tested seeds.

where,n dis the number of germinated seeds on a given dayd,dis the number of days after the start of the experiment,andNgis the total number of seeds germinated (Daws et al.2002; Xia et al.2016).

where,GMDis mean daily germination.The peak day is the day when the most seeds had germinated.ΣGPis the cumulative germination percentage,PVis the peak value, which is represented as the daily mean germination percentage from the beginning of the test to the peak day (Reum et al.2018).

Data analyses

The data sets were tested for normality by using normal probability plots.Arcsine-square-root or log transformation was applied to meet the assumptions of ANOVA (Seiwa et al.2009).Two-way ANOVA was adopted to test for differences inGP,TM,GVand phytohormones in embryos and endosperms of seeds after storage in different light and temperature conditions.Differences atP≤ 0.05 were considered significant.SPSS 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all calucaltions and analyses.Graphs were generated by SigmaPlot 14.0 (SYSTAT, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

GA 3 , ABA levels in seeds in response to storage light and temperature conditions

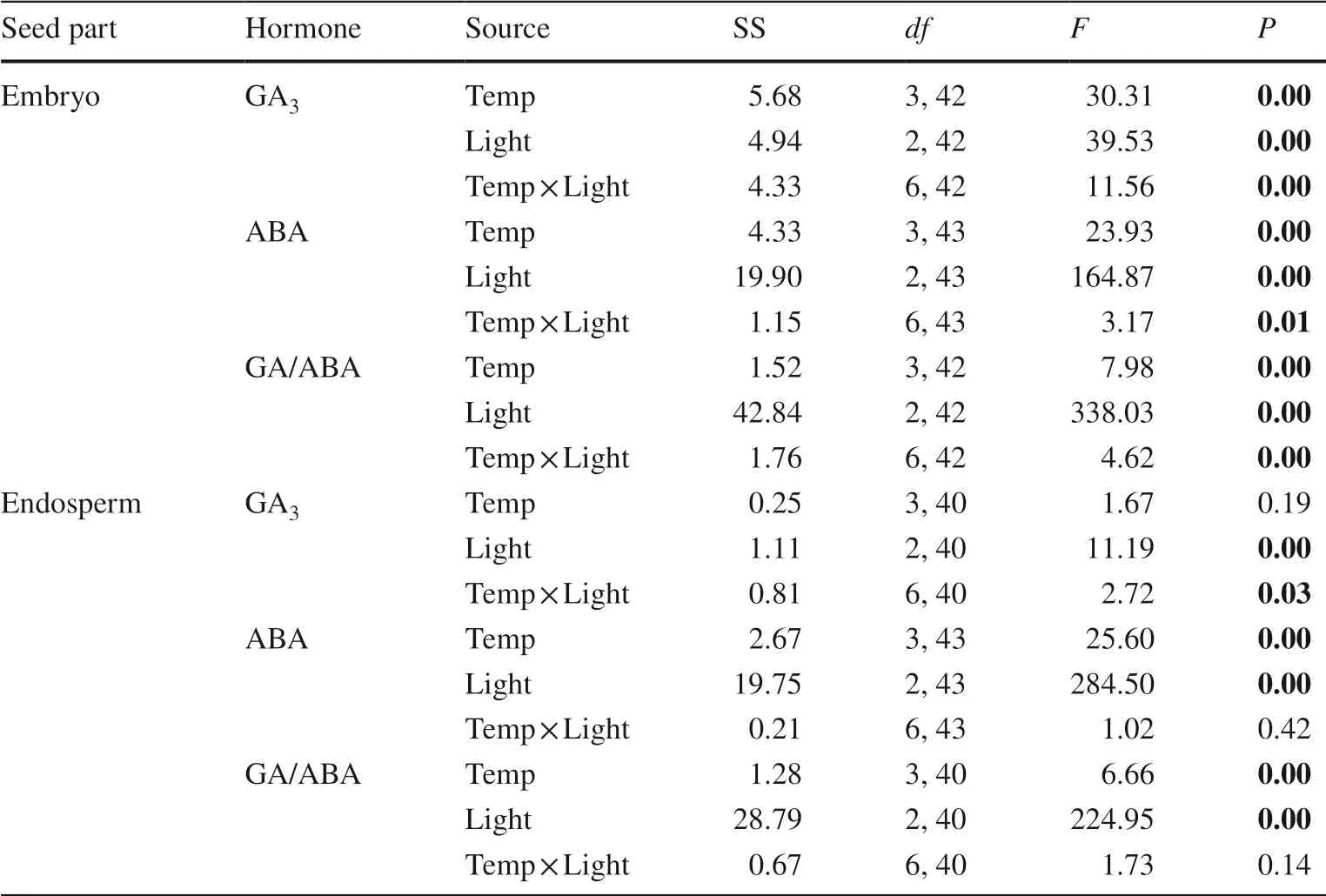

Light and temperature each had a significant effect on GA3and ABA concentrations and the ratio of GA/ABA in the embryo and endosperm, except for temperature, which had no significant effect on GA3in the endosperm (Table 1).The interaction effect oflight and temperature was also significant for GA3concentration in the embryo and endosperm and for ABA and GA/ABA in the embryo but not for ABA or GA/ABA in endosperm (Table 1).GA3concentrations in the embryo in L0 and in the endosperm in L200 decreased with temperatures from T-5 to T25 (Fig.2).From T25 to T15, GA3concentrations in the embryo and endosperm in all the three light levels stayed almost the same.In L20,GA3concentrations in the embryo and endosperm of seeds varied insignificantly with the temperature levels.At T-5,the GA3concentration in L200 was significantly higher than in L20 and L0 in the endosperm, but in L200 and L20 was significantly lower than in L0 in the embryo.However, at T25 and T15, no significant differences were found for GA3concentrations in the embryo and endosperm among all the three light conditions (Fig.2).The ABA concentrations in the embryo and endosperm had a similar trend in response to the temperature levels; they decreased from T-5 to T25 and increased as the temperature decreased from T25 to T15(Fig.2).In all light treatments, the ABA concentrations in the embryo and endosperm were the lowest at T25 (Fig.2).The ABA concentrations in L20 were significantly higher than in L200 and L0 for all temperatures (Fig.2).In the embryo, GA/ABA decreased as temperature increased (in the order T-5, T5, T25, T15) in L200 and L0,but in L20 increased as the temperature increased from T-5 to T25 and decreased from T25 to T15.In the endosperm,GA/ABA increased from T-5 to T25 and decreased from T25 to T15 in all three light levels (Fig.2).

Table 1 Two-way ANOVA of phytohormones in embryo and endosperm of Pinus koraiensis seeds after storage in different light and temperature regimes

Fig.2 GA 3, ABA and GA/ABA in the embryo and endosperm ofimbibed seeds of Pinus koraiensis seeds in different light levels and temperatures.L200 is 200 μmol m- 2 s- 1 , L20 is 20 μmol m- 2 s- 1 , L0 is 0 μmol m- 2 s- 1 ;T-5: - 5 °C (50 days), T5: - 5 °C(50 days) + 5 °C (50 days),T25: - 5 °C (50 days) + 5 °C(50 days) + 25 °C (50 days),T15: - 5 °C (50 days) + 5 °C(50 days) + 25 °C(50 days) + 15 °C (50 days).Different capital letters indicate a significant difference in phytohormone concentrations among different light levels at the same temperature.Different small letters indicate a significant difference in phytohormone concentrations among different temperatures in the same light

Germination of P.koraiensis seeds in response to light and storage temperature

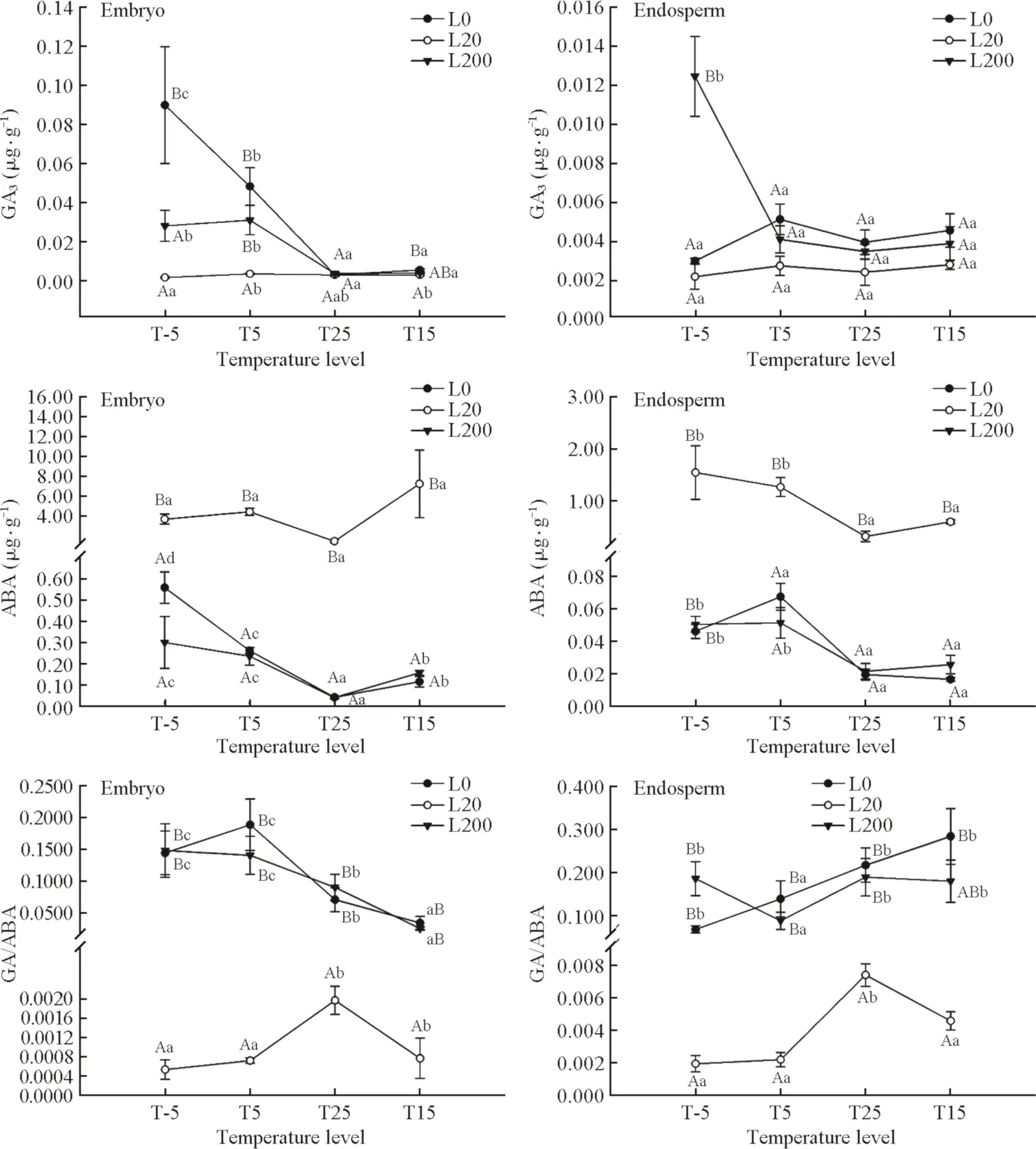

GP,TMandGVfor seeds were significantly affected by light,temperature and their interaction (Table 2).At T-5, T5 and T25,GPin L200 and L20 was significantly higher than in the dark (Fig.3).At T15,GPdid not differ significantly among L200, L20 and L0.Moreover,GPfor T-5/ L200 was below 40% and below 10%, for T-5 / L20.To summarize, the positive effect oflight on dormancy release and germination ofP.koraiensisseeds apparently relies on optimum temperatures at T5 and T25.

Table 2 Two-way ANOVA of germination percentage ( GP) ,mean germination time ( TM) and germination value ( GV) of Pinus koraiensis seeds after storage in different light and temperature regimes

Fig.3 Germination percentage ( GP ) of Pinus koraiensis seeds in different light and temperature regimes.L200 is 200 μmol m -2 s -1 ,L20 is 20 μmol m -2 s -1 , L0 is 0 μmol m -2 s -1 ; T-5: - 5 °C (50 days),T5: - 5 °C (50 days) + 5 °C (50 days), T25: - 5 °C (50 days) + 5 °C(50 days) + 25 °C (50 days), T15: - 5 °C (50 days) + 5 °C(50 days) + 25 °C (50 days) + 15 °C (50 days).Different capital letters indicate a significant difference in GP among different temperatures in the same light.Different small letters indicate a significant difference in GP among different light levels at the same temperature

In all light conditions,GPfor seeds stored at T5 and T25 was significantly higher than at T-5 and T15 (Fig.3), indicating that the optimum temperature for germination of the seeds was T5 and T25.

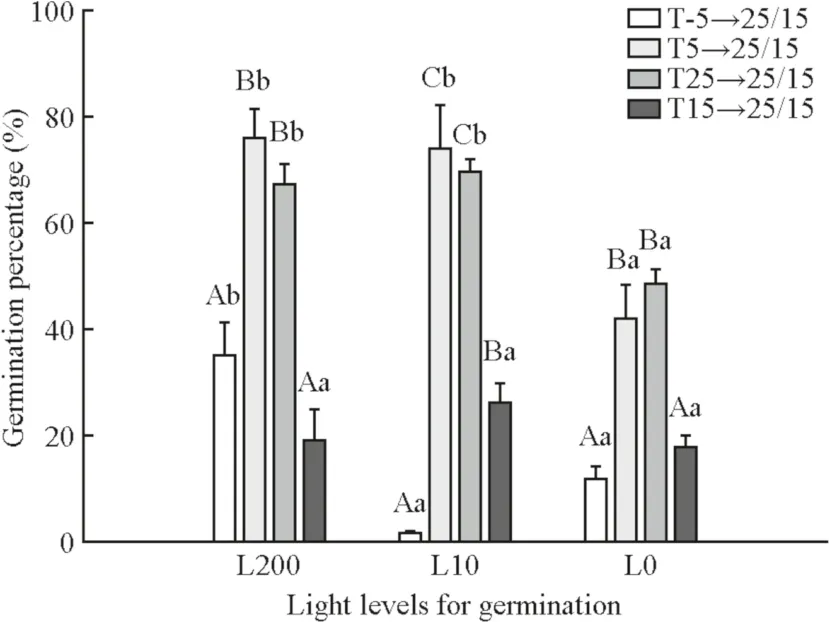

TMwas the longest in L200/T-5 and L0/T-5 and the shortest in L200/T15 and L0/T15 (Fig.4).In L20,TMat T5 and T15 was significantly longer than at T-5 and T25.In all light levels,TMwas longer at T5 than at T25.At T5,TMwas significantly higher in L0 than in the other light levels.

The effect oflight and temperature onGVwas similar to that onGP(Fig.4).At T5 and T25,GVwas significantly higher in L200 and L20 than in L0.No significant differences were found among all three light levels at T-5 and T15 (Fig.4).For all three light levels,GVwas significantly higher at T25 than at T-5, T5 and T15 (Fig.4).

Fig.4 Mean germination time ( TM) and germination value ( GV) of Pinus koraiensis seeds in different light and temperature regimes.L200 is 200 μmol m- 2 s- 1 , L20 is 20 μmol m- 2 s- 1 , L0 is 0 μmol m- 2 s- 1 ; T-5 → 25/15, T5 → 25/15, T25 → 25/15 and T15 → 25/15 represent germination test at 25 °C/15 °C after storage at T-5, T5, T25 and T15, respectively.Different capital letters indicate a significant difference in TM ( GV ) among different temperatures in the same light.Different small letters indicate a significant difference in TM ( GV ) among different light levels at the same temperature

Correlation between GA, ABA, GA/ABA and germination

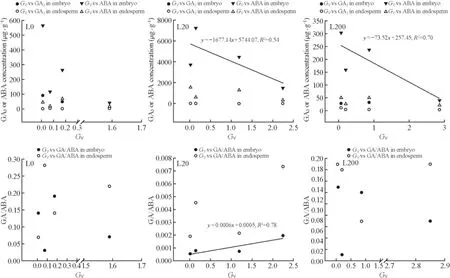

With respect to the relationship between the phytohormones andGVof seeds, significantly negative correlations were found between ABA concentrations in the embryo andGVfor both L20 and L200 (Fig.5).In addition, the GA/ABA in embryo was significantly positively correlated withGVfor L20 (Fig.5).However, no observable correlations betweenGVand GA3or ABA concentrations in either the embryo or endosperm were found for L0 (Fig.5).

Fig.5 Correlations between germination value ( GV ) and GA or ABA concentrations and GA/ABA in the embryo and endosperm of P.koraiensis seeds.L200 is 200 μmol m -2 s -1 , L20 is 20 μmol m -2 s -1 , L0 is 0 μmol m -2 s -1

Discussion

Temperature has been known to regulate both dormancy and germination (Bewley and Black 1994; Pons 2000; Baskin and Baskin 2004; Fenner and Thompson 2005), but whether light is also a regulator of dormancy has been under debate.In the present study, without light irradiance (L0 light treatment), theGPreached 40–60% after a specific period of stratification at suitable temperatures (T5, T25) (Fig.3)but was less than 40% in L200 and less than 10% in L20,at T-5.Song and Zhu ( 2016) adopted theGPthreshold to define the dormancy and dormancy release ofP.koraiensisseeds; seeds were dormant if theGPwas below 10% and completely released from dormancy when theGPwas higher than 80%.According to this criterion, we concluded that light was not the necessary factor for dormancy release ofP.koraiensisseeds and that the role of temperature on dormancy release was far more important than light.We also confirmed that the light and temperature treatments need to be carried out in a set order for them to be effective at releasing dormancy;that is, light must come last to be effective (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger 2006).In addition,temperature was demonstrated to work over time to alter the depth of dormancy, whereas light was an immediate way to make conditions suitable for germination.As the storage temperature changed in the order T-5, T5, T25, T15,GPandGVincreased first, then decreased in all light levels(Figs.3, 4), whereas the ABA concentrations changed in the opposite directions (Fig.2).These results demonstrated that the dormancy ofP.koraiensisseeds was released when the storage temperature increased from T-5 to T25 but was initiated again when the temperature decreased from T25 to T15 through the whole stratification period.

Light and temperature regulate seed germination for many species (Pons 2000; Baskin and Baskin 2004; Fenner and Thompson 2005).ForP.koraiensisseeds, in all light levels, theGPandGVwere higher at T5 and T25 than at T-5 and T15 (Figs.3, 4), demonstrating the critical role of temperature on germination.Thus, we considered T5 and T25 as the optimum temperature conditions for primary dormancy release.Low temperatures (0 to 5 °C) have been known to be efficient for primary dormancy release ofP.koraiensisseeds (Song and Zhu 2016), whereas high temperature delays dormancy release and induces secondary dormancy in several plant species (Larsen and Eriksen 2004; Brändel 2005; Song and Zhu 2016).However, we found that high temperature (25 °C) immediately after a low temperature(5 °C) treatment also facilitated dormancy release by shortening the germination process (Fig.4) and elevating theGV(Fig.4) ofP.koraiensisseeds.These different results also suggest that the effect of temperature on dormancy induction is not only dependent on the prevailing temperature, but also on the temperature experienced by seeds during a previous dormancy release and the resulting dormancy status of the seed population (Malavert et al.2017).Moreover, a gradual increase in the ambient temperature is required for the induction of secondary dormancy of two Carex species by high temperature (Brändel and Schütz 2003).

In addition, theGPandGVwere higher in L200 and L20 than in the dark (L0) at optimum temperatures; thus, light irradiance facilitated germination ofP.koraiensisseeds.The positive effect oflight on seed germination ofP.pinaster,P.sylvestris,P.koraiensishas also been confirmed previously (Ruano et al.2009; Gaudio et al.2011; Zhang et al.2015).Flores et al.( 2011) proposed that sensitivity to light during seed germination was a key strategy to prevent gemination when the place or time was unfavorable for seedling establishment.Because the effect oflight on germination disappeared when the stratification temperature decreased from 25 °C to 15 °C (Figs.3, 4), we speculate that light is not effective for germination after secondary dormancy is induced by a temperature decrease from 25 to 15 °C and this might be a strategy forP.koraiensisto avoid germination during subsequently unfavorable seasons (such as winter).

GA stimulates seed germination, and ABA initializes seed dormancy (Bewley 1997; Chen et al.2008; Miransari and Smith 2014; Deng et al.2016; Guo et al.2020).However,the variations in GA3levels did not parallel theGPorGVpatterns in response to light or temperature, which indicates that GA did not act as the stimulator forP.koraiensisgermination in this study.Although GA3and ABA contents were affected significantly by the stratification light and temperature levels (Table 1), no consistent trend was found between the GA3or ABA concentrations and the finalGPin the three light levels with any temperature treatment.Thus, the phytohormone levels induced by the light treatments were not the cause of the dormancy release.The changes in the ABA concentrations in response to changes in storage temperatures were opposite the changes inGPorGV, demonstrating that ABA levels contributed to theGPresults at different temperatures.A specific period of stratification at the optimum temperature (T5 and T25) might thus facilitate a change in the ABA concentration to further promoted dormancy release inP.koraiensisseeds.This result is in accordance with the finding that temperature conditions during the cold stratification period can affect the dormancy depth ofP.koraiensisseeds (Song and Zhu 2016; Song et al.2020b).Therefore,the impacts oflight and temperature on seed germination are likely due to different pathways.Light regulation of seed germination has been reported to be controlled by GA or ABA biosynthesis through the action of phytochrome (Oh et al.2006; Seo et al.2009) and that temperature affects seed germination directly through GAs and ABA levels (Argyris et al.2008; Song et al.2020b) or the sensitivity to GA or ABA concentrations (Xia et al.2019).The germination advantages in forest gaps with greater light transmittance are suggested to be due to greater temperature fluctuations(Pearson et al.2002).Nevertheless, we found higherGPandGVin L200 and L20 than in the dark after storage at T5 and T25.This result further revealed that light can affect seed germination directly instead indirectly through an effect on temperature.Further research is needed to fully elucidate the metabolic pathways and molecular mechanisms involved in light regulation of seed germination.

In addition to our study, other studies have also shown that seed germination performances are regulated by the ratio of ABA/GA rather than the absolute amounts of either GA or ABA (Bicalho et al.2015; Liu and Zhang 2016).Interestingly, in light L20 and L200,GVwas negatively correlated with ABA concentrations in the embryo ofP.koraiensisseeds.In L20,GVwas positively correlated with GA/ABA in the embryo ofP.koraiensisseeds.However,germination was not significantly correlated with phytohormone levels inP.koraiensisseeds in the dark.These results indicated that attributes of seed germination that are controlled by the changes in the ABA concentrations or the GA/ABA ratios, which are generated by temperature levels, are dependent on the light conditions.Light irradiance seems to enhance the response ofP.koraiensisseeds to phytohormone levels caused by temperature variations.Thus, light and temperature are coupled in their effect on phytohormone levels to induce germination ofP.koraiensisseeds.

Conclusions

Temperature affected the dormancy release, but light was not necessary for the primary dormancy release ofPinus koraiensisseeds.The dormancy release ofP.koraiensisseeds was closely related to a decrease in ABA concentration, which varied with temperature levels.Both temperature and light influenced the germination ofP.koraiensisseeds.At the optimum stratification temperature (T5 and T25), light irradiance accelerated germination.Germination was controlled by the decrease in ABA concentration or an increase in GA/ABA in embryo in L200 and L20.Light irradiance might enhance the response of seeds to phytohormone changes caused by temperature variation.The specific pathways involved in light regulation of the germination ofP.koraiensisseeds through phytochromes by acting on phytohormone levels or the sensitivity to phytohormone concentration need further research.

AcknowledgementsWe thank Professor Shihong Luo and his research team from Shenyang Agricultural University for phytohormone analyses.Thanks are also due to Mr.Gang Xu at Liaoning Provincial College of Communications and Ms.Shuang Xu at the Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences for their help with the germination experiment and sample preparation for the phytohormone analyses.

Open AccessThis article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material.If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http:// creat iveco mmons.org/ licen ses/ by/4.0/.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Journal of Forestry Research

- Reversibly photochromic wood constructed by depositing microencapsulated/polydimethylsiloxane composite coating

- Surveillance of pine wilt disease by high resolution satellite

- Adaptation of pine wood nematode, Bursap helenchus xylophilus,early in its interaction with two P inus species that differ in resistance

- Pine wilt disease detection in high-resolution UAV images using object-oriented classification

- Transcriptome analysis shows nicotinamide seed treatment alters expression of genes involved in defense and epigenetic processes in roots of seedlings of Picea abies