Soil organic carbon storage in forest restoration models and environmental conditions

2022-09-08RanieriRibeiroPaulaMiguelCalmonMariaLeonorLopesAssadEduardodeMendon

Ranieri Ribeiro Paula·Miguel Calmon ·Maria Leonor Lopes-Assad·Eduardo de Sá Mendonça

Abstract The scale of forest and landscape restoration is expected to increase during the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and its contribution to the provision of critical ecosystem services to society.Several models of forest restoration may improve ecosystem services, including soil organic carbon (SOC) storage.A review was carried out to access: (1) the variability of SOC storage between worldwide forest restoration models and, (2) the effects of climate, soil class, soil texture, and vegetation type on SOC storage.We reviewed 119 primary studies with information on SOC and soil texture for different forest restoration models.The restoration models were grouped into four categories: natural regeneration, monocultures, agroforestry,and mixed forest.SOC data was extracted from these four restoration models, other land uses (cropland, bare land,grassland, and natural forest), climate regimes, and soil properties.The SOC storage in the forest restoration models and other land uses at a global scale ranged between 0.1 to 514 Mg ha -1 .The overall mean value for SOC storage was higher for natural regeneration (112 Mg ha -1 ), followed by agroforestry (74 Mg ha -1 ), mixed forest (73 Mg ha -1 ), and monocultures (68 Mg ha -1 ).However, the average SOC storage was similar among the four restoration models in the moist warm climate zone.The SOC storage mean value in the moist cool zone was 23% higher than the dry cool zone(81 and 62 Mg ha -1 , respectively), and 50% higher for the moist warm zone when compared to the dry warm climatic zone (74 and 38 Mg ha -1 , respectively).The SOC storage of the restoration models was positively related to soil depth(0.59; p < 0.01), clay content (0.29; p < 0.01), and stand age(0.17; p < 0.01).Globally, the mean values of SOC storage were 26, 66, and 139 Mg ha -1 at zero - 10, zero - 30, and zero - 100 cm depths, respectively.In addition, sandy soils showed smaller mean values of SOC storage than medium to clay soils, especially in deeper soil layers.Furthermore, SOC storage was positively related between restoration models and other land uses (0.93; p < 0.01), suggesting a prominent effect of climate and soil properties on SOC.Forest restoration models showed larger SOC storage when compared to croplands and bare land, but in general it was smaller or similar when compared to pasture and natural forest.

Keywords Forest restoration·Land uses·Soil type·Soil texture·Climate

Introduction

Soils are the most important interfaces for life and provide nutrients and water for plant growth, which in turn is the basis for all heterotrophic life, including humans (Gleixner 2013).Soil organic carbon (SOC), one of the components of soil organic matter (SOM), is a heterogeneous pool of C comprised of diverse materials as fine fragments of litter, roots and soil fauna, microbial biomass, products of microbial decay and other biotic processes, and compounds such as sugar and polysaccharides.The dynamics of organic matter in the soil depend on the pool in which SOM is located.Two large pools are generally considered and defined according to their degree of protection (protected and unprotected SOM), and depend on their time on the soil (Kravchenko et al.2015).Easily degradable compounds can persist for years to decades (Kleber 2010), while highly aromatic organic compounds such as lignin or charcoal can degrade in a matter of a few to thousands of years (Lehmann et al.2015).SOC storage is a result of SOM processing,which seems to depend on physical, chemical, and biological processes rather than on the age of the soil carbon (Sierra et al.2018).

The loss of SOC due to land use change is the second major cause of the increase in CO2in the atmosphere after fossil fuel emissions (Bispo et al.2017; Lal 2018).The magnitude of SOC loss is related to management intensity(Laganière et al.2010), which leads to losses by decomposition, burning and volatilization of CO2, and leaching of dissolved C compounds.Thus, good practices and management of vegetation and soil are highly recommended for the maintenance and increase of soil C in agricultural lands (Minasny et al.2017; Lal 2018; Chenu et al.2019).Some of the management techniques that affect the inputs and content of soil C are tree pruning (Oelbermann et al.2006; de Carvalho et al.2014), thinnings (Ma et al.2018),lime (Mosquera-Losada et al.2015), fertilizer application(Adams et al.2005), irrigation (Pegoraro et al.2010), and site preparation intensity (Garcia-Franco et al.2014).

Forest restoration on bare or degraded lands have a major potential for C storage and sequestration (Guo and Gifford 2002; Laganière et al.2010).However, the inputs of C from trees into the soil vary widely depending on environmental conditions, time ofintervention, species (or genotypes),and diversity (Pregitzer and Euskirchen 2004; Erskine et al.2006).Furthermore, the decomposition of litter and the inputs of C from plants into the soil are affected by the functional traits of species (De Deyn et al.2008; Mueller et al.2015), and functional groups such as nitrogen-fixing tree species (Barlow et al.2007; Macedo et al.2008).Net primary production (NPP) is the result of carbon accumulated in plant biomass and the amount lost by respiration in one-time intervals.The maximum NPP in natural ecosystems occurs in tropical forests, followed by temperate forests, croplands, tropical savannas and grasslands, temperate grasslands and shrublands, boreal forests, deserts,and tundra (Gough 2011).A recent review of studies has identified several drivers and indicators of SOC storage for different spatial scales in the world (Wiesmeier et al.2019).The climate regulates NPP and is an important driver of SOC at larger scales, as well as the vegetation type.Soil texture, especially clay content, is also an important indicator of SOC storage, independent of scale.In addition, soil depth is another parameter for measuring soil C storage; stand age often has little effect on soil C storage (Yang et al.2011).

The magnitude of carbon sequestration and storage has been debated among forestry experts, policymakers, investors, and researchers (Thamo and Pannell 2016).The scale of forest restoration will likely increase in the next few decades to keep temperature increase below 2 °C and maintain the provision of ecosystem services for society’s well-being.The UN Decade of Ecosystems Restoration started in 2021 to help accelerate and increase the scale of forest restoration over the next 10 years.In Brazil, for example, there is an estimated deficit of 21 million hectares on legal reserves and permanent preservation areas to comply with the Forest Law (Soares-Filho et al.2014).

Several models of forest restoration, such as natural regeneration, monoculture plantations, agroforestry systems,and mixed forests will improve the provision of ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration and storage.A review was undertaken to access: (1) the variability of SOC between forest restoration models worldwide; and, (2) the effects of climate, soil class and soil texture, and vegetation type on SOC storage.In addition, a potential way to increase soil C sequestration and SOC storage is discussed.

Material and methods

Articles selection

The search was on primary field studies with information on soil organic carbon storage and soil texture in forest restoration models.The review followed a three-stage process, considering the string < soil carbon storage or stock or sequestration and texture and trees or forest or agroforestry or restoration or natural regeneration > , in different combinations, according to the website database considered (Supplementary materials–Appendix A: Protocol Review).Two authors defined the methodology to be adopted for selection,inclusion and exclusion of studies and data.

Two inclusion criteria were used for article selection: (1)field studies showing estimates or with the possibility to calculate SOC storage associated with some model of forest restoration; and, (2) field studies with information on soil texture (textural class or clay content).In addition, exclusion criteria were applied such as: (1) studies without mention in the title, abstract or keywords of the forest restoration model examined; (2) studies applying models to predict the SOC without showing actual data for one specific model of forest restoration]; and, (3) studies with an unavailable or inaccessible to download pdf via the Brazilian Qualis CAPES( www.capes.gov.br).

During the first stage, there was the search for articles in Scielo, Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science published by November 2019.A total of 1752 articles were recovered in these databases (Supplementary materials–Appendix A: Protocol Review).After the first scan for duplicate articles, 932 articles remained.At the second stage,titles, abstracts, and keywords of these 932 articles were examined.This resulted in the selection of 277 articles and were viewed on the web and filtered through inclusion and exclusion criteria that resulted in 120 articles.

The third stage encompassed a search on Google Scholar,with the string < soil carbon sequestration or soil carbon stock and texture and agroforestry and forest and trees and Brazil > .This search generated 6630 result pages and the first 23 pages were evaluated, resulting in 63 articles with 9 duplicates.Therefore, a total of 54 studies were included in the database.At the end of these three stages, 174 articles were reviewed in detail to verify all inclusion and exclusion criteria.This last step resulted in 119 studies that were included in the Mendeley software and produced 501 data points for SOC storage.

Data extraction and compilation

For each of the 119 scientific articles, name(s) of the author(s), country, climatic zone, forest restoration model,dominant tree genera and age, soil type, texture and depth,clay content, and SOC storage (in the literature also referred to as SOC stock, SOC pool or SOC density) were extracted.The number of repetitions for the restoration model was not considered.An average value of SOC storage was extracted of the forest restoration models in each stand age, associated to data on vegetation, soil, and climate.The studies showed average values of SOC storage from plots allocated at different spatial scales.Specific data on SOC storage from other land uses, when available in the articles, also was collected.Land use information was categorized into bare land, cropland, grassland, and natural ecosystems.Natural ecosystems were prioritized in studies that had two or more reference areas.Soil depth was equal between restoration model and reference area.SOC data for maximum soil depth was often recovered, but soil depth was prioritized along with information about soil texture.When the data were represented in figures, the extraction was done with the program Plot Digitizer version 2.6.8.

Data of soil climate and vegetation attributes were standardized for the analysis, and soil depth to cm and clay content to %.An average value for studies was calculated that reported a range of clay content and stand age.In addition,this review included estimates of the SOC storage reported directly in the articles or estimated using reported values of SOC concentration, soil depth and bulk density.In articles that only reported SOC concentration values and soil density, SOC storages were estimated by:

SOCstorage=SOCconcentration×L×DB×104

where SOC storage is soil organic carbon storage (Mg ha-1),SOC concentration the concentration of organic carbon in the soil (g C g-1soil), L the thickness of the soil layer (m),and DB the soil bulk density (Mg m-3).

Nomenclature of soil type varied largely because of the different classification systems used by each country.The World Reference Base (WRB) of the FAO was used to standardize the soil classification of each study area.Moreover, the climate division suggested by Smith et al.( 2008)and Abdalla et al.( 2018), based on thermal and moisture regimes, was used.The warm zone covered the tropical and subtropical regions; the cool zone covered temperate and boreal regions (both continental, sub-continental and oceanic).Zones with precipitation higher than 500 mm per year were classified as moist, and with equal and lower than 500 mm as dry zones.

The studies were grouped into four restoration models:(1) natural regeneration, (2) monoculture plantations, (3)agroforestry system, and (4) mixed forest.All secondary forest data (N=39) were considered as natural regeneration.To define the reference areas, the following groups were used:bare land (N=2), cropland (N=20), grassland (N=11), and natural ecosystems (N=45).This resulted in 5, 98, 39, and 145 pairs of comparisons for SOC storage between reference area and forest restoration models.The amount of data for the reference areas were lower than for the forest restoration models because most articles contained on average four data points per restoration model and only one for reference area.Grassland was considered to be ecosystems with grass dominant such as planted pasture (managed or unmanaged)and natural grass.Further, natural ecosystems were considered in the following categories: forests, savanna, caatinga,and desert.

Data analysis

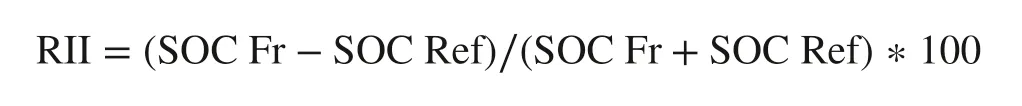

A histogram was used to show the amount of data by forest age, soil depth, clay content, and SOC storage for the forest restoration models and other land use, and the net difference in SOC storage.The RII index adapted from Armas et al.( 2004) was used to account for the net difference in SOC storage, which is the difference in SOC storage between the forest restoration model and the reference area.The index was originally proposed to measure the relative interaction intensity in the plant community, and the following equation was adapted:

where RII is the net difference in SOC storage expressed as%, SOC Fr is the soil organic C storage in the forest restoration model in Mg ha-1, and SOC Refis the soil organic C storage in reference areas in Mg ha-1.

The variability of SOC storage between the forest restoration models at a global level was assessed using mean values and standard errors.In addition, SOC storage was assessed in three specific soil layers (zero - 10, zero - 30,and zero - 100 cm).Studies that reported these specific soil layers were used to illustrate the effects of depth, texture,soil type, and climate on SOC storage in forest restoration models.Further, mean values in the upper 30 cm layer and subsoil (> 30 cm) was accounted for each soil group, considering all data that reported SOC storage between these soil depths.

SOC storage was related to depth, clay content, and stand age at a global level using the Spearman correlation coefficient, also used to assess the relationship between the SOC storage data for the set of restoration models and the reference area at the global level.Data analysis was performed on Microsoft Excel® and SigmaPlot 13 (Systat 2014).

Results

Characterization of the dataset

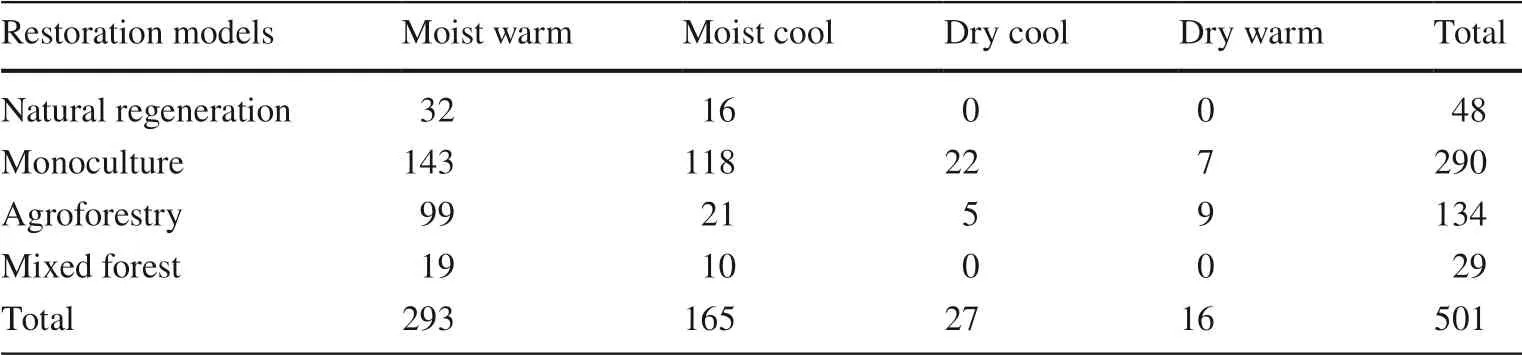

The 119 scientific articles in the dataset were published from 1991 to 2019, with approximately 70% published from 2011.The 501 data points of SOC storage were unevenly distributed between restoration models, climatic zones, dominant genera, and soil types.Most data referred to moist climate zones (Table 1).SOC storage data in the forest restoration model with only one species (monoculture) represented 58%of the total data at the global level, followed by agroforestry(27%), natural regeneration (9%), and mixed forest (6%).

Fifty-four dominant genera were identified with 384 data points on SOC storage.A total of 115 data points referred to the forest restoration model with two or more dominant tree genera (mixed).There were 35, 20, eight, and two dominant genera reported in moist warm, moist cool, dry cool, and dry warm zones, respectively.The number of data points for each genus, as well as the range of SOC storage, soil depth and clay content, and stand age are shown in Table S1.Twenty-seven genera had only one or two data points.The most reported genera wereEucalyptus(N=74),Populus(N=53), andPinus(N=50).The dominant genera data for the moist warm climate zone wereEucalyptus,Pinus,Theobroma,Populus, andBambusa, and for moist cool climate zone,Pinus,Pseudotsuga,Abies,Fagus, andQuercus.These dominant genera were mainly in monoculture plantations.

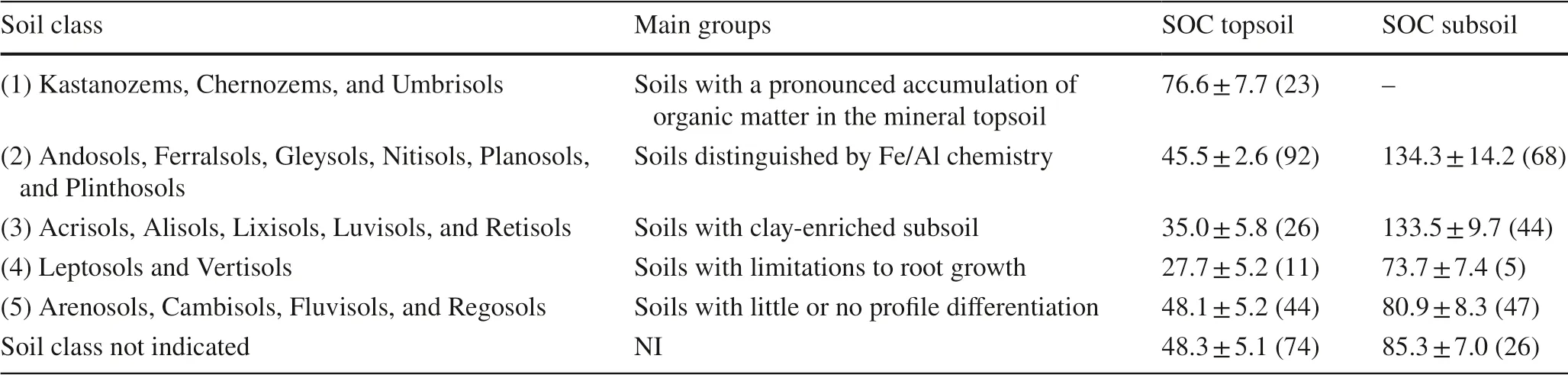

Several soil classes were identified using three different systems: Soil Taxonomy, World Reference Base (WRB), and the Brazilian System of Soil Classification.Considering the differences between soil types, and SOC levels in the different soil types, the soil was reclassified using five of the WRB´s reference soil groups (Table 2).The reclassified soil types and the number of data points in each class, as well as the main information on SOC storage, soil depth, stand age,and clay content are shown in Table S2.

Table 1 Total number of data points of soil organic carbon storage by restoration type and climate zone

Table 2 Soil classes identified in the selected articles, their distribution in five groups from the World Reference Base (IUSS 2015), and mean values (± standard error) of SOC storage (Mg ha -1 ) in the top 30 cm soil layer and in the subsoil (> 30 cm)

The data points included forest restoration models with stand ages up to 160 years.However, 81% of the data points had stand ages up to 40 years (Fig.1 a).Average values ranged between 18, 20, 35, and 36 years for agroforestry,monoculture, natural regeneration, and mixed forest, respectively.Soil depth ranged from 5 to 300 cm, although 73%was within the 60 cm depth and most were in the first 30 cm layer (Fig.1 b).Approximately 76% of the soils had low(< 20%) to medium (20–40%) clay content (Fig.1 c).

SOC storage variability

For the restoration models, the SOC storage values ranged from 0.1 to 456 Mg ha-1and 77% of the data points indicated SOC storage values < 100 Mg ha-1(Fig.1 d).The maximum value in the reference area was 514 Mg ha-1, and 77%of the data points had values < 100 Mg ha-1(Fig.1 e).The net difference in SOC storage between models and reference area ranged between - 42 and + 88%, but for 80% of the data points, the differences were between ± 20% (Fig.1 f).

Fig.1 Histograms with a the number of reports by vegetation age in years, b clay content in %, c soil depth in cm, and d SOC storage in forest restoration types, e in reference area, and f the net difference in SOC storage in Mg ha -1

The overall average for SOC storage at the global level was higher for natural regeneration (112 ± 16 Mg ha-1),followed by agroforestry (74 ± 6 Mg ha-1), mixed forest(73 ± 13 Mg ha-1), and monoculture (68 ± 3 Mg ha-1).The overall average for SOC storage at the global level for bare land, cropland, grassland, and natural ecosystems was 57 ± 16, 60 ± 4, 102 ± 12, and 89 ± 9 Mg ha-1, respectively.

The mean SOC storage values in the four restoration models were similar in the moist warm climate zone, ranging between 70 and 83 Mg ha-1.Furthermore, the mean SOC storage values between monoculture, agroforestry, and mixed forest were in the same range as in the moist cool zone (68–82 Mg ha-1).The largest SOC storage was under natural regeneration in the cool climate zone (172 Mg ha-1).

Factors affecting SOC storage

The overall mean of SOC storage in the moist cool zone was 23% higher than the dry cool zone (81 ± 5 and 62 ± 11 Mg ha-1, respectively), and 50% higher for the moist warm zone compared to the dry warm zone (74 ± 4 and 38 ± 9 Mg ha-1, respectively).In addition, the mean SOC storage values were higher in the upper 30 cm soil layer in restoration models in the moist cool (66 ± 5 Mg ha-1)and dry cool climate zones (61 ± 12 Mg ha-1) than in the moist warm (38 ± 2 Mg ha-1) and dry warm climate zones(32 ± 3 Mg ha-1).In contrast, the SOC storage values were higher in the upper 100 cm soil depth in the moist warm(125 ± 7 Mg ha-1) and moist cool zones (98 ± 10 Mg ha-1)than in the dry warm (38 ± 11 Mg ha-1) and dry cool zones(74 ± 18 Mg ha-1).

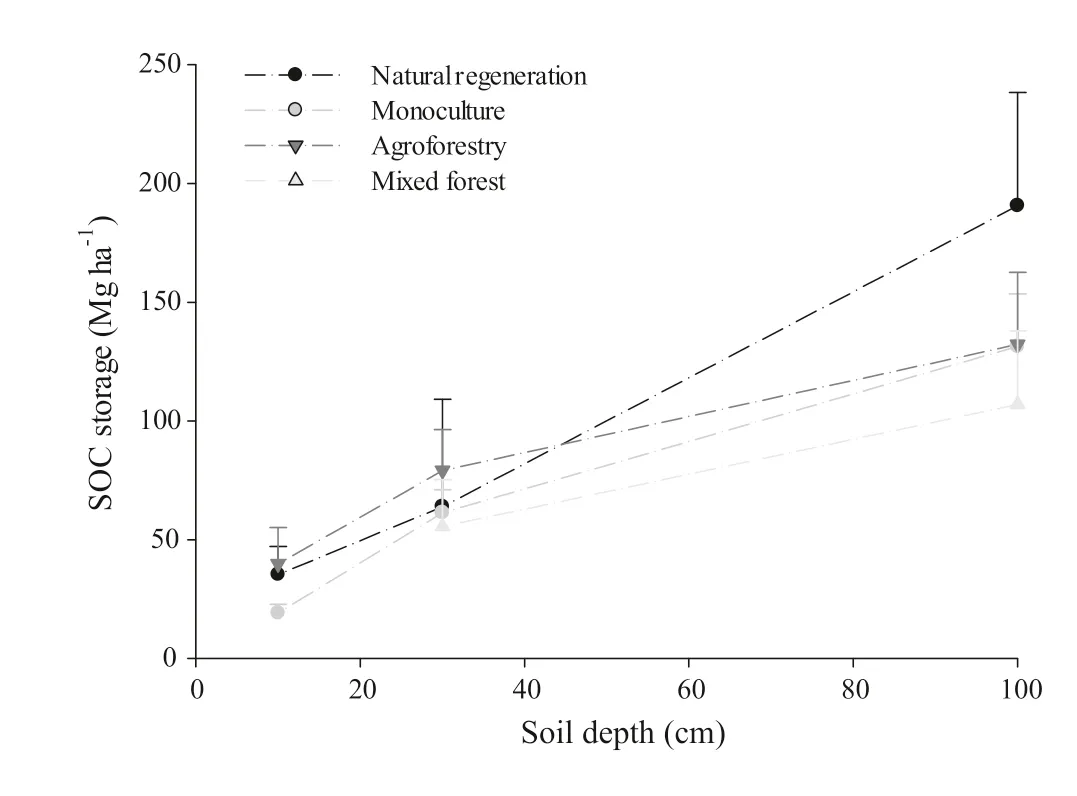

The increase in soil depth, clay content, and stand age were positively correlated to the increase in SOC storage at the global level, with Spearman correlation values of 0.59 (N=501;p< 0.01), 0.29 (N=412;p< 0.01), and 0.17(N=484; p< 0.01), respectively.Worldwide, the mean values of SOC storage were 26, 66 and 139 Mg ha-1the upper 10-cm, 30-cm and 100-cm layers, respectively.There were subtle differences in levels of SOC storage by depth between restoration models.A smaller mean SOC storage value was found monocultures in the 10-cm soil depth (19 Mg ha-1),and larger values were found under natural regeneration in the upper 100-cm soil layer (191 Mg ha-1) (Fig.2).

Fig.2 Mean values of SOC storage (Mg ha -1 ) in forest restoration models at the global level in the 10 cm, 30 cm, and 100 cm soil layers; the number of data points for each restoration model ranged between 0–28, 2–40, and 12–35, in the 0–10, 0–30, and 0–100 cm soil depth.The bars indicate standard error

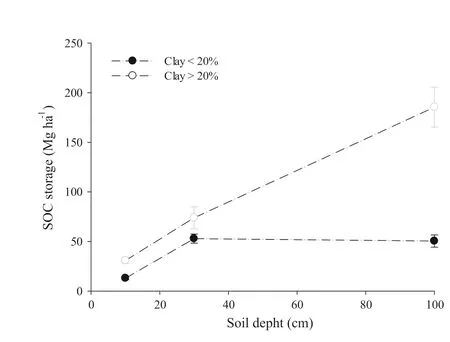

At the global level, soils with clay contents < 20% (sandy soils) showed smaller average SOC storage values than soils with clay contents > 20% in all soil depths (Fig.3).Further,in the upper 100 cm layers, clay soils showed up to four times more SOC storage than sandy soils.

Fig.3 Mean values of SOC storage (Mg ha -1 ) in sandy soil (clay content < 20%) and clay soil (clay content > 20%) at 0–10, 0–30,and 0–100 cm depths of forest restoration models at the global level;number of data points for each soil depth ranged between 14 and 34 to sandy soil, and between 21 and 41 to clay soil.The bars indicate the standard error

The average SOC storage value was higher in the upper 30 cm soil layer with a pronounced accumulation in the mineral topsoil, and a smaller amount in soil layers limiting root growth (Table 2).The mean SOC storage value was higher in subsoil (> 30 cm) of soil groups with higher clay contents and distinguished by Fe/Al ions.For example, the Ferralsols,which are very weathered soils with dominant kaolinite and Fe/Al oxides, had a mean value of 48 to 162 Mg ha-1of SOC at the 19 cm and 73 cm depths, respectively.Cambisols, showing little development of soil structure and B horizon, had 46 to 121 Mg ha-1of SOC at the 22 cm to 61 cm depths.Acrisols, with high base content and low-activity clays enriching the subsoil, had 25 to 143 Mg ha-1of SOC at the 10 cm to 95 cm depths, respectively.Luvisols, however,with high base content and high-activity clays enriching the subsoil, had 80 to 190 Mg ha-1of SOC at the 12 cm to 153 cm depths.Finally, the Podzols had 30 to 85 Mg ha-1of SOC at the 10 cm to 40 cm depth, respectively.

SOC storage values in the upper 10, 30 and 100 cm layers were unevenly distributed by soil order in our data base(Fig.4).However, Andosols and Ferralsols have higher SOC storage in the upper 100 cm layer than the other soil orders,with up to 316 and 240 Mg ha-1.

Fig.4 Mean values of SOC storage (Mg ha -1 ) at 0–10, 0–30, and 0–100 cm soil depths of the identified soils in database; number of data points by soil depth ranged between 0 and 24; bars indicate the standard error

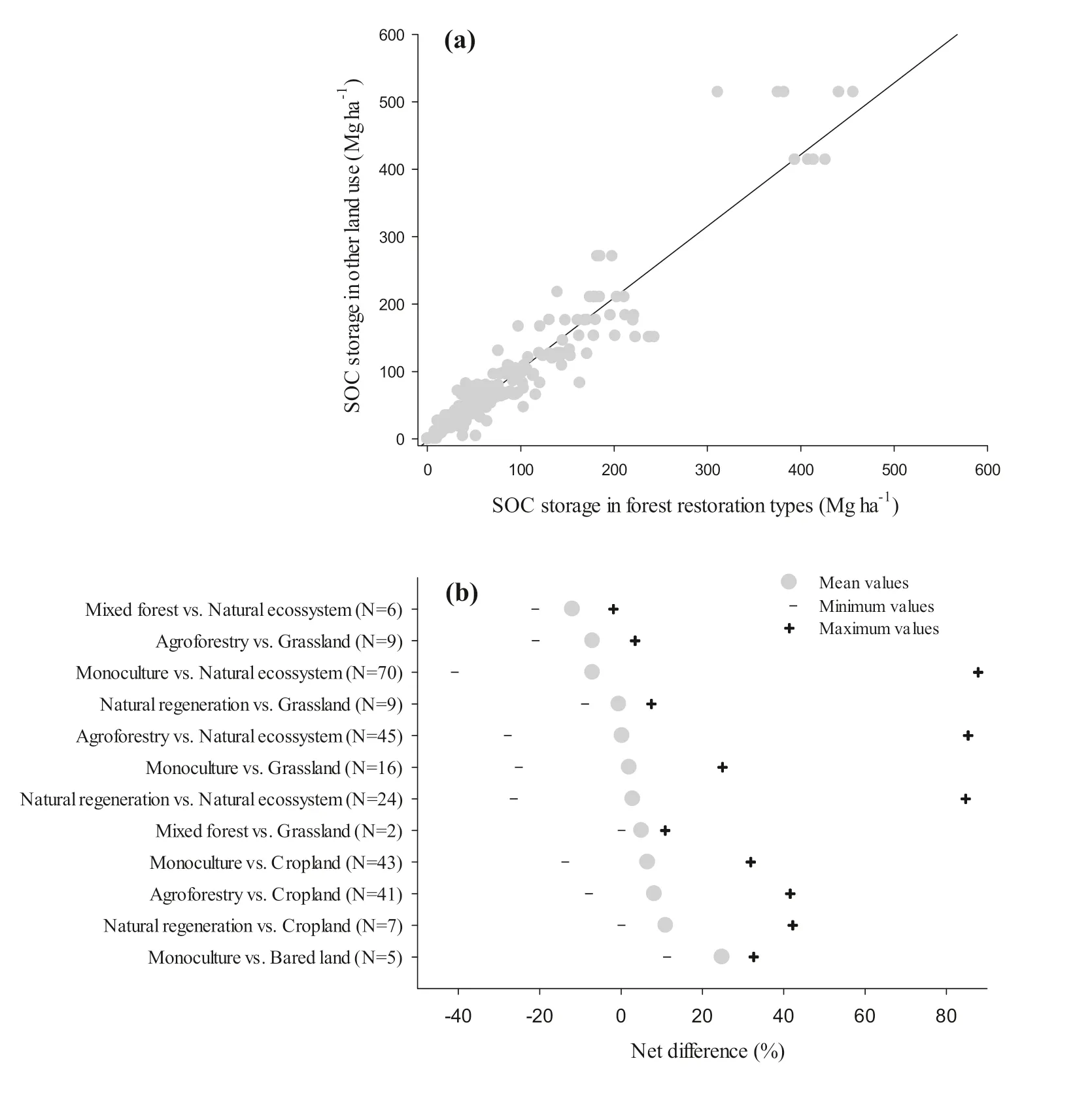

The SOC storage in the forest restoration models and reference area (area under other land use) was significantly correlated at the global level (Fig.5 a), with R2values higher than 0.93 (N=277; p< 0.01).Globally, the mean values of net difference were remarkably positive,suggesting higher SOC storage in forest restoration models than in other land uses (Fig.5 b).On average, there was a difference of 5 and 25% between restoration models and cropland or bare land.However, when the reference areas were natural ecosystems and grasslands, the net difference of SOC storage was often neutral or negative.

Fig.5 a relationship between SOC storage in forest restoration types and other land uses at the global level and b the minimum mean and maximum values of net differences of SOC storage between forest restoration models and other land uses; number of comparisons is shown in brackets

Discussion

SOC variability by vegetation type

In this review, the wide variability of SOC data and high correlation between SOC in forest restoration models and reference areas suggest a strong effect of other factors such as climate, soil type, depth and clay content.Forest restoration models showed average SOC values often higher than in croplands and ecosystems such as deserts.The traditional management of croplands results in soil disturbance and in general larger loss of C compared to grasslands and forested ecosystems, both showed higher mean SOC storage values in our data set.The greater SOC storage under grasslands relative to forests and agriculture can be associated with the management and functional traits of plants (Abdalla et al.2018).The patterns observed in this study for net differences in SOC storage are consistent with other studies at the global level (Guo and Gifford 2002; Marín-Spiotta and Sharma 2013; Shi et al.2016; Chatterjee et al.2018; Guo et al.2021), and in Brazil (Zanatta et al.2020).

The age of forest restoration is a controversial factor that influences SOC storage.Older forests are expected to contain more SOC than younger restoration models.This was confirmed by a positive and significant Spearman correlation between SOC storage and stand age, although with a low value.While the average net difference in SOC storage between forest restoration models and other land uses was close to zero for stands up to 30 years of age at the global level, forest restoration models older than 30 years showed a positive net difference of 5.5%.However, this was also affected by the net difference in moist cool and dry cool zones by 34% and 4%, respectively.In moist warm climates,the net difference was negative for restoration models older than 30 years.This difference is caused mainly by monoculture plantations that showed a net difference of - 9% on average (Smith et al.2002; Kasel and Bennett 2007; Lima et al.2008).A few studies on chronosequences with ages of 2 to 50 years-old and soil with low amounts of clay (Isaac et al.2005; Uri et al.2014; Smal et al.2019) had contrasting results.Higher and lower SOC storage in the topsoil after restoration depended on the history of land use and the predominant vegetation type.In general, the positive effect of forest restoration models is higher and more rapid when compared to croplands and degraded soils, but not after the conversion of a natural ecosystem such as forest.However,some exceptions occurred when natural ecosystems such as deserts and savannas were used to compare forest restoration models (e.g.Pulrolnik et al.2009; Su et al.2010; Tonucci et al.2011).

SOC storage was most probably affected by forest restoration model and dominant tree genera.Soil management intensity in monocultures may explain the smaller values of SOC in the upper 10-cm layer in monocultures (Laganière et al.2010).Moreover, the restoration model withPinusshowed a negative net difference in SOC storage in the moist warm climate zone (Lemma et al.2006; Kasel and Bennett 2007) and moist cool climate zone (Nadal-Romero et al.2016; Smal et al.2019).In contrast, models withPopulusshowed positive net differences in both climatic zones(Gupta et al.2009; Deng et al.2016).Furthermore, studies show a lower SOC storage in reforestation withEucalyptuscompared to the reference area.Some exceptions, however,were observed mainly on clay soils (Corazza et al.1999;Lemma et al.2006; Pulrolnik et al.2009; Medeiros et al.2018).

Advances in knowledge on the effect of trees on SOC storage were obtained using isotopic techniques.The natural abundance of the13C isotope varies largely in soil cultivated with plants with C3 and C4 metabolism, which enables the measurement of C pools derived from each type of plant.Using this technique, Monroe et al.( 2016) found that cacao trees were more efficient in changing SOC than rubber trees after four years of planting.Cypress and eucalypt stands also contributed to a higher change in SOC thanPinus(Lemma et al.2006).Pulrolnik et al.( 2009) showed that SOC from eucalyptus contributed 5% to the new SOC in the upper 10 cm soil layer after 20 years using a savanna soil as a reference).The use ofisotopes also showed a higher contribution of mixed eucalyptus and guachapele to SOC than a monoculture of both species (Balieiro et al.2008).A more sophisticated isotopic technique with14C showed a small contribution of C (< 1%) derived fromPinusstands to carbon pools in coarse soils after 40 years (Richter et al.1999).

The number of studies in Brazil with forest restoration models were higher for monoculture plantations (N=73)than for agroforestry (N=42).Most studies with monocultures were withEucalyptus(N=59), followed byHevea(N=8), andPinus(N=5).Few studies had data from mixed forests and from natural regeneration, with only 5 and 11 data points, respectively.The SOC storage was, in general,lower in forest restoration models compared to natural forests and grasslands, with average values of - 6.5% (N=46)and - 3.9% (N=24), respectively.Some comparisons between croplands (N=3) and monocultures withEucalyptusshowed a positive average net difference of + 2.4%inEucalyptusthan in croplands (Medeiros et al.2018).A few studies showed a positive net difference between monocultures withHevea(Maggiotto et al.2014; Vicente et al.2016) andPinus(Cassol et al.2019) versus grasslands.In comparison to natural forests, the following differences were found:Theobroma(+ 14.6%; N=2) (Barreto et al.2008;Gama-Rodrigues et al.2010),Euxylophora(+ 8.6%; N=1)(Smith et al.2002), andScherolobium(+ 3.0%; N=1) (da Silva et al.2009).

Environment effects on SOC at different scales

Storage of soil organic carbon depend on the balance between carbon inputs, mainly from vegetation, and outputs or turnover, mainly from carbon mineralization, erosion,and leaching.SOM turnover is faster in moist than in dry climatic conditions, as well as faster in warm than in cool climates.Therefore, the accumulation of SOM is in general higher in cooler climate conditions, with higher SOM storage in boreal and temperate regions compared to tropical and subtropical regions (Stockmann et al.2013; Gou et al.2021).This pattern could explain the higher SOC storage in natural regeneration than in other models in the moist cool climate zone.However, climate alone did not explain SOC storage in the different types of forest restoration models.It is important to highlight that soils differ according to forming factors, as parent material, bioclimate, and topography, and the contribution of different soil groups to SOC storages varies at the global level (Kogel-Knabner and Amelung 2021).

Pedogenic processes, such as eluviation, illuviation,turbation, and decomposition rate of organic materials,are related to the increase or decrease of soil organic matter (Duchaufour 1977) or soil organic carbon storage.The increase of SOC with soil depth is, therefore, expected to occur due to increasing soil volume.Thus, differences between SOC storage in the topsoil and subsoil among soil groups is often influenced by soil order.In addition, changes in soil texture can be correlated with the amount of SOC stored (Walter et al.2015; Conforti et al.2016).Among the soil classes and environment conditions assessed in this study, sandy soils (clay < 20%) have similar average SOC storage levels in the topsoil (average 21 cm; 42 Mg ha-1)and subsoil (average 90 cm; 59 Mg ha-1).Medium textured soils (20–40% clay) show more significant differences in SOC storage, ranging from 56 to 130 Mg ha-1, for depths of 20 and 81 cm, respectively.A similar trend occurs for clay soils (clay > 40%), where the SOC storage ranged from 47 and 153 Mg ha-1for average depths of 21 and 79 cm, respectively.The slight differences in SOC in the first 100 cm in sandy soils could be related to soil structure, its relationship with water regime, and SOM turnover.In sandy soils, the structural organization is weak, soil macroporosity (pores with diameters ≥ 0.08 mm) is high, and with intensive leaching and aeration, resulting in a high organic matter turnover.However, medium textured clay soils have a more structural organization than sandy soils, affecting SOM turnover in a different way (Oades 1988).

Potential to increase soil C sequestration and SOC storage

Studies of estimates of carbon sequestration in forest restoration showed average values (± SD) of 1.8 ± 1.4 Mg ha-1a-1.These are higher than estimates for agriculture systems(0.05–1.0 Mg ha-1a-1) with best management practices (Lal 2018).The estimates for soil C sequestration were generally higher for natural regeneration and agroforestry compared to mixed forests and monoculture plantations, with 2.3 Mg ha-1a-1and 1.2 Mg ha-1a-1, respectively.However,the rate of change in SOC influenced by the forest restoration models depends on soil type and properties, especially in the amount of clay.Average carbon sequestration in the studies were slightly higher in sandy than medium to clay soils, with an average of 1.9 ± 1.1 and 1.4 ± 1.2 Mg ha-1a-1,respectively.

Some studies also showed a synergistic effect of forest restoration models and management techniques.This was the case of a study done by Macedo et al.( 2008) to recover degraded land that had the topsoil removed and planted with mixed-planting of seven N2-fixing legumes trees (mainly exotic species) inoculated with rhizobium for N2-fixing and arbuscular mycorrhizal.The erosion caused by the removal of the topsoil was minimized by the planting of bamboo.The management techniques that favor the biological activity of the soil, and minimize losses of C due to soil erosion, runoff,and deep drainage, have shown to be effective to increase SOC storage (Laganière et al.2010).Other studies showed that plantations that include N2-fixing trees have higher SOC content than non-N2-fixing trees (Marín-Spiotta and Sharma 2013; Shi et al.2016).In general, the mean SOC storage values in forest restoration models that had N2-fixing trees were higher than the average of other genera.Some examples areRobinia,Gliricidia,Leucaena,Alnus,Erythrina,Albizia, andIngagenera.However, restoration models withLeucaenaandIngagenera showed SOC storage mean values lower than the reference areas, in moist warm climate zone and 0–30-cm soil depth.In contrast,Robinia.AcaciaandGliricidiagenera showed a positive net difference in relation to reference areas.

The positive effect of species mixture on SOC has been shown by other studies (Hulvey et al.2013; Chen et al.2019).Although our review was not intended to assess the effects of tree diversity on SOC storage, in the short- to medium-term the diversity of trees may have a small effect on SOC storage and other soil properties in the topsoil when compared to a soil that was disturbed (Laganière et al.2010;Nogueira Jr.et al.2011).Nogueira Jr.et al.( 2011) showed that mixed-species plantation with five fast-growing species established by direct seeding (minimum tillage) had a higher impact on soil properties (e.g.SOC storage, fertility,microbial biomass) when compared to plantations of mixedspecies with 41 species using seedlings and conventional tillage.The areas under natural regeneration with spontaneous mixed-species vegetation and no management, however,had similar soil proprieties than old native forests (Nogueira Jr.et al.2011).

Conclusion

The SOC values ranging from 0.1 to 456 Mg ha-1among the four forest restoration models assessed in our review demonstrate the large variability of SOC storage worldwide.At the same time, the mean values of SOC storage among the forest restoration models were similar in most warm climate.The influence of forest restoration models on SOC storage was uncertain because of climate, soil type,soil depth, and clay content.The importance of climate and soil as key drivers of SOC storage was corroborated by the strong relationship between SOC storage of forest restoration models and the reference areas at the global scale.The climate had an effect on SOC storage in the forest restoration models.The amount of SOC in dry climate conditions was 23–50% lower than moist climate conditions.Furthermore,the clay content affected SOC storage mainly in deeper layers where the mean values of SOC storage were up to four times higher in medium to clay soils than sandy soils.This larger pools of SOC storage in the subsoil could be effective in minimizing the loss of C due to land use and climate change.The positive effect of forest restoration models on SOC storage was often found in croplands, bare lands, and some natural ecosystems, such as deserts.The SOC storage in forest restoration models was lower or similar when compared to grasslands and natural forests.Our review suggests that several forest restoration models can improve SOC,especially when associated with a sustainable and diversified inputs of organic matter with minimal soil interventions over time.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to thank the World Resources Institute for the financial support, theConselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científi co e Tecnológico(CNPq) for fellowships of the first author (Process Numbers 159972/2018-3), and theUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santo(UFES) and toCoordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior(Capes) for access to the data bases.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict ofinterestThe authors declare that they have no conflict ofinterest.

杂志排行

Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Journal of Forestry Research

- Reversibly photochromic wood constructed by depositing microencapsulated/polydimethylsiloxane composite coating

- Surveillance of pine wilt disease by high resolution satellite

- Adaptation of pine wood nematode, Bursap helenchus xylophilus,early in its interaction with two P inus species that differ in resistance

- Pine wilt disease detection in high-resolution UAV images using object-oriented classification

- Transcriptome analysis shows nicotinamide seed treatment alters expression of genes involved in defense and epigenetic processes in roots of seedlings of Picea abies