Nü Perspectives

2022-06-15贺文文

贺文文

Do female characters in Chinese cinema and TV pass the Bechdel test?

國产剧的女性角色为什么鲜有“正常人”?

The camera follows the man’s gaze as it falls first on the woman’s neck, then down to her bare legs. It lingers over her messy hair and slightly parted lips, ending on her hands, which are putting sugar-coated fruits on bamboo sticks. Feeling his presence, she turns her head back, and the two major characters lock eyes for the first time.

This scene, shot using the “male-gaze,” is from the TV show , which aired on state broadcaster CCTV in January this year and explores one family’s experience of China’s momentous historic changes in the industrial Northeast. Despite considerable hype from the network and high ratings—it received the highest viewer figures of any program on the CCTV-1 channel over the last three years, and a rare 8.1 rating out of 10 from hard-to-please viewers on reviews site Douban for its talented cast and tear-jerking script—not everyone is so enamored with the show.

Ye Yingying, a public welfare lecturer on female and elderly psychology, is one of a number of people to have called out the objectification of ’s female characters, especially Zheng Juan, subjected to the male gaze in the scene above. “She would always endure and accept everything without complaint, and always put all her effort into taking care of her children and in-laws,” says Ye. She feels that the character is a deliberate “morally perfect symbol” intended to model certain behaviors to women, such as “[having] no ego, always enduring, never rebelling.”

Ye’s comments could be applied to any number of Chinese TV series which have been slammed on review sites in recent years for their one-dimensional portrayals of female characters. Decades of stereotypical female characters in film and TV, driven by social expectations, are weighing on female audiences and industry insiders who are now seeking alternatives.

In March, viewers criticized Tencent Video and other video streaming platforms for using terms such as “plastic sisterhood” and “sisters who hold grudges” to promote the 2018 HBO series in China. Fans decried the use of competition and negativity as selling points for a drama series that is focused on the companionship and mutual empowerment between its two female leads.

Recent years have seen an uptick in the number of shows purporting to tell women’s stories, with one notable example being the Vicki Zhao-helmed (2020) drama series, which examined issues around domestic abuse, beauty standards, and mid-life crises.

Yet efforts at portraying more female viewpoints have not always been successful. Film director Li Yingyi tells TWOC that female characters that are presented with a strong individualist streak are still largely lacking because mainstream Chinese culture is so focused on family values. “Not as many people like to watch [female individualists], which leads to less market investment, fewer writers creating such characters, and in the end, viewers having fewer opportunities to see these characters [on screen],” says Li, whose film, following a female teacher grappling with a student’s death, was screened at China’s FIRST International Film Festival in 2019.

Li commends some recent TV dramas for trying to portray deeper female characters: such as (2022), which delves into the unequal responsibilities faced by men and women in child-raising; and (2021), whose three female protagonists experience struggles and have conversations unrelated to men, and actually call out the portrayal of women on TV as either damsels in distress or manipulative shrews in one episode. “It hasn’t been systematized, but it’s growing,” Li says.

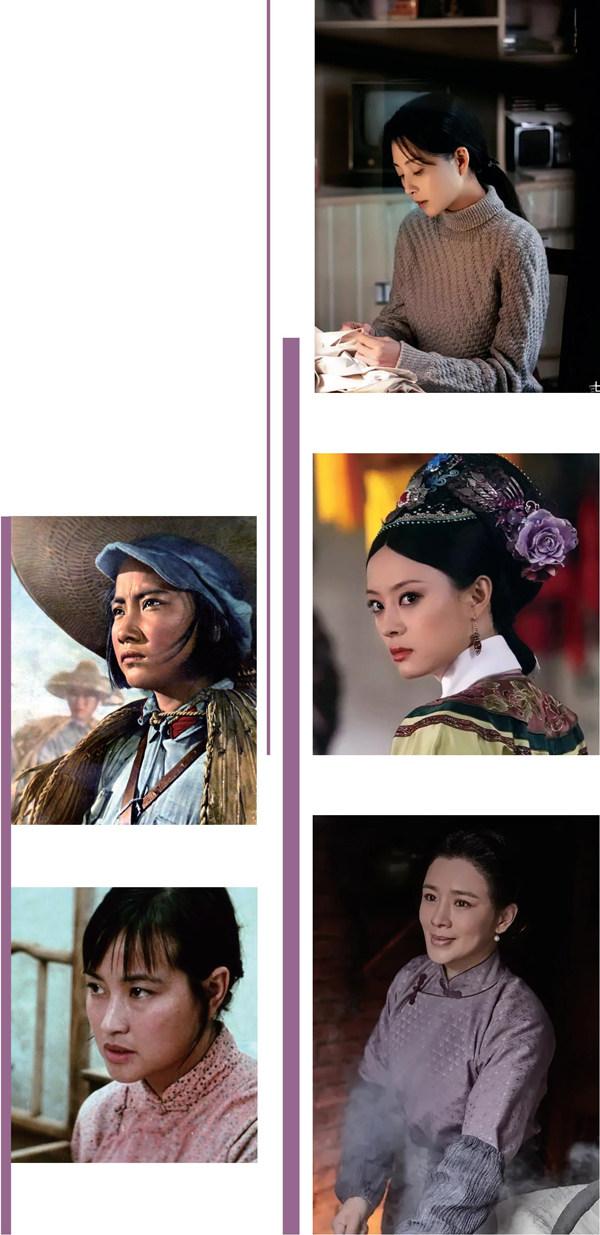

Female characters in Chinese film and TV weren’t always like this. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, women were encouraged to view themselves in roles beyond the domestic sphere. On screen, women were presented as emancipated, escaping from domestic oppression to fight against the Nationalists, as with the strong-willed Wu Qionghua in (1961); or foregoing their personal appearance to focus on class struggle, such as (1950), a biopic of the titular revolutionary famous for her plain and androgynous style of dress.

Nevertheless, negative associations of femininity persisted—they were simply projected onto class enemies instead. In the film (1958), for example, Liu Nina, a stereotypical feminine character obsessed with make-up, jewelry, and high heels, is a spy for the Japanese and Nationalist forces.

Variations on this imagery were used repeatedly until the reform period of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the female as a mother figure came to the fore. Director Xie Jin, who had earlier shot , typified this shift with his famous “scar trilogy” examining the Cultural Revolution. In (1981), (1982), and (1987), gun-wielding revolutionaries are replaced with diligent, obedient, and maternal figures as the female leads.

By the 1990s, there was a return of objectification. Women became subjects of the male gaze in films such as Jiang Wen’s Golden Lion Award-nominated (1994), which presented the female character Milan as the object of the teenage protagonists’ sexual fantasies.

Hong Kong and Taiwanese shows also swept across the Chinese mainland during this period, bringing other pervasive images for women to model themselves on. Taiwanese dramas adapted from the novels of Qiong Yao were particularly influential. Shows such as (1996) and (1990) gave female characters a single mission: to fall in love.

More recently, there has been a spate of programming on Chinese screens that has purported to tell better stories about the country’s female population. Guduo Data, an online statistics platform for TV dramas and movies, calculates that of the 294 dramas that were broadcasted online in 2020, 63 percent were targeted at female viewers. So-called “female-led series (大女主電视剧),” featuring female protagonists or ensemble casts, have been popular for years, especially on online streaming platforms, with the likes of contemporary urban soap opera (2020) and female-centric imperial drama (2018).

One of the first hits of the genre was the hugely successful (2011), which tells the story of politics within the imperial harem of the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911). The show met with widespread acclaim, registering a 9.3 out of 10 rating on Douban, and securing distribution deals in Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore. But while fans praised the show for its complex, intelligent, and proactive female cast, critics noted that the plot still revolved around women competing for power they gain from their relationship to a man.

Despite the proliferation of female-oriented series, audiences and scholars have questioned whether their characters are helping to break down gender-based stereotypes, or merely reinforcing them. “If you ask me what I think about these shows with strong female heroines, then I can only support them, right? Because these strong female figures are in contrast to the evil and weak portrayals that we’ve seen before,” cultural critic Dai Jinhua told video-sharing platform Zaojiu in 2019.

But Dai pointed out that these shows don’t actually change the balance of power between genders. “The women [in the show] face a cultural Mulan-like situation: For you to perform, you have to be presented like a man. If female characters are just another version of men and are logically indistinguishable, then it’s not particularly fresh and not particularly valuable.”

Producers and directors must also consider government regulations which, while not precisely codifying how characters should and shouldn’t be written, tend to encourage traditional family values. Due to the “high degree of control over the ideological content of television dramas,” wrote Ya-chien Huang of Tamkang University in the book back in 2008. “In most cases, producers impose self-censorship to make money and avoid trouble.” The National Radio and Television’s General Rules for TV Content Production from 2016 include a ban on “abnormal sexual relations” and “promoting unhealthy views of marriage.”

While there’s plenty of criticism in Hollywood of works that don’t pass the “Bechdel test”—of having female characters with motivations unrelated to men—some Chinese viewers cite positive examples of international shows and films that are trying to depict women more realistically and in more diverse ways. Viewer Su Jing, a 38-year-old marketing professional, feels that Western series such as (2017) and have more “humanity.” “They are humans who have careers, romantic plots, and concerns,” she tells TWOC. “They’re not just mothers and wives serving as plot devices, but well-rounded characters.”

Some directors are trying to create these well-rounded characters, though Li observes it is challenging for lots of female directors to get these projects greenlit by producers “unless we [can] show some examples [of successful shows] which can draw investment.” According to a study by the One International Film Festival, China’s only female-focused film festival, only around 10 percent of domestic films produced each year between 2017 and 2021 were directed by women, and around 24 percent of films revolve broadly around female or feminist themes such as women’s personal growth and relationships.

Li has been working on a movie based on the lives of housewives, mainly inspired by her own experiences. “My mother was a housewife, and I was surrounded by housewives,” says Li, mentioning that the movie will be about a housewife who has been trying to get pregnant for the last three years and who reveals a secret about herself. Li isn’t worried about the market, as she believes young audiences still want to watch this kind of film.

Li doesn’t have many details about the female characters in her film right now, telling TWOC that she prefers not to set this in stone. “There will be a very important female character in my movie, and I will focus on the character and explore her personality, her social environment, and her relations with others in that specific time.”